Digital Threats to Social Movements

What You’ll Learn

- What threat modeling is

- Who is engaged in surveillance and the strategies they use

- Examples of tactics and programs used in surveillance

Social movements challenging powerful individuals, organizations, and social structures face a broad range of surveillance risks. Specific threats vary widely in technical sophistication, likelihood, and potential for harm. Threat modeling is a process whereby an organization or individual considers their range of adversaries, estimates the likelihood of their various data and devices falling victim to attack, and finally considers the damage done if attacks were to succeed. (And then they work to protect the data that is most at risk and that would be the most damaging to lose or have accessed.)

We think about surveillance in the following order to inform how to protect oneself:

- Who is your adversary? Is it a neighborhood Nazi who is taking revenge on you for your Black Lives Matter lawn sign? Is it an oil corporation that is fighting your antipipeline activism? Is it the US government trying to prevent you from whistleblowing? By understanding who your adversary is, you can surmise their resources and capabilities.

- Is your adversary going after you in particular, are they trying to discover who you are, or are they collecting a lot of information in the hopes of getting your information? What surveillance strategy are they likely to employ? This will help you understand what type of data and where your data may be at risk.

- What particular surveillance tactics will your adversary employ to get that desired data? This will help you understand how to protect that data.

We examine surveillance risks starting with the adversary because it is strategic to do so. No one can achieve perfect digital security, but one can be smart about where to spend one’s effort in protecting oneself against surveillance. In an actual threat-modeling discussion within an organization or social movement, who potential adversaries are is often more readily apparent than how such adversaries would carry out attacks. Who the adversary is then informs the range of techniques available to that adversary (depending on their available resources and legal authorities) and, in turn, what protective behaviors and technologies the organization can employ.

Surveillance Adversaries

We generally think of adversaries in terms of what resources they have available to them. For the purposes of this book, we will limit ourselves to three adversary categories:

Nation-states have access to the most resources in a way that may make it seem like their surveillance capabilities are limitless. Even so, they are unlikely to be able to break strong encryptions. Here, we think of the National Security Agency (NSA) as the entity with access to the most sophisticated surveillance capabilities. The disclosures by Edward Snowden in 2013 give the most comprehensive window into nation-state-level capabilities and are searchable in the Snowden Surveillance Archive.

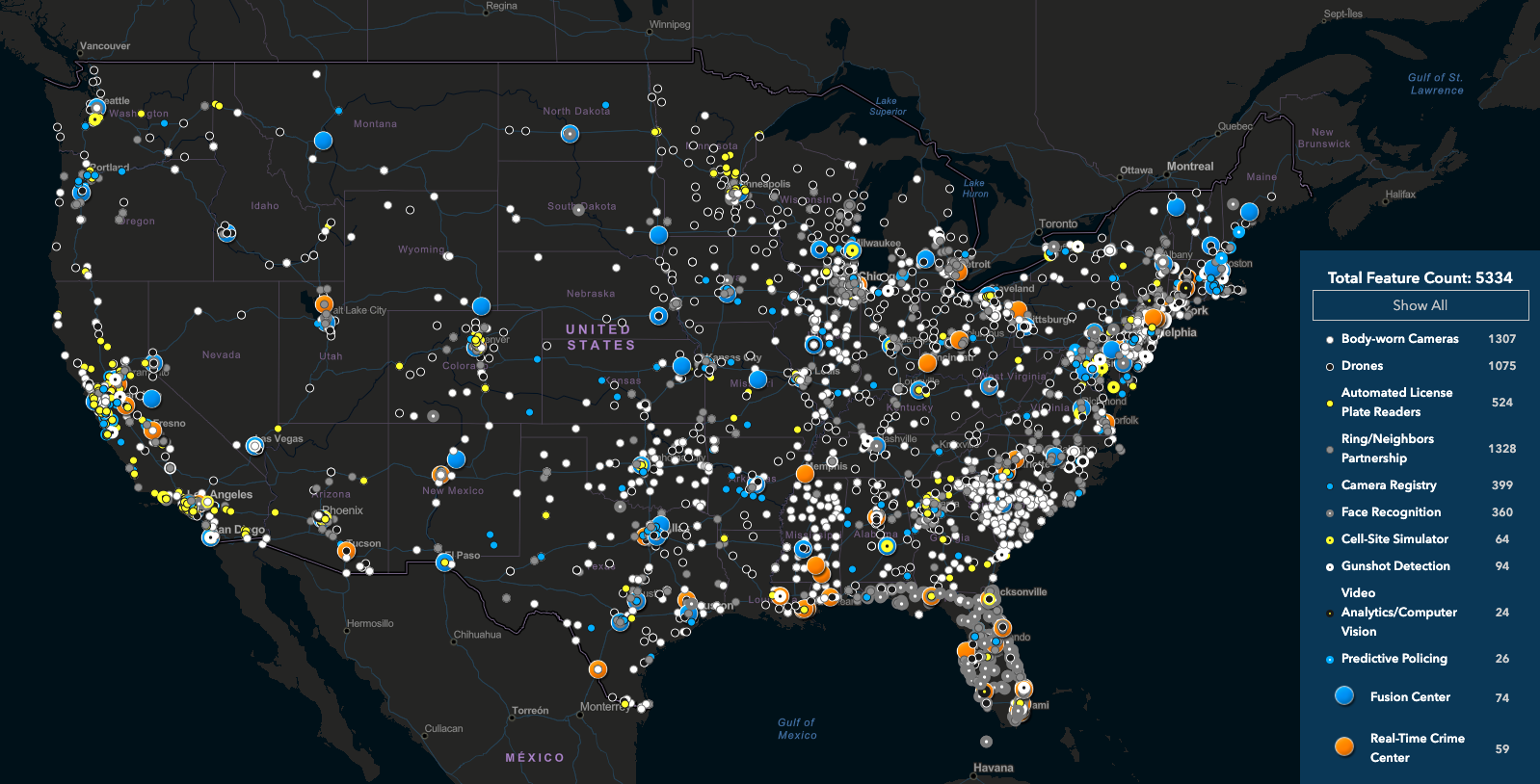

Large corporations and local law enforcement are often heavily resourced and share information with each other but don’t necessarily have access to the capabilities of nation-states. However, the use of technology to aid in surveillance is widespread among law enforcement agencies in the US, as illustrated below in this screenshot from Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Atlas of Surveillance.

Individuals have the least resources but might know you personally and so be able to more effectively use social engineering to obtain your data.

Note that techniques available to lower-resourced adversaries are also available to higher-resourced adversaries. As an example, corporations and law enforcement employ informants and infiltrators, who may be individuals who know you personally. Also, while more sophisticated surveillance capabilities are not usually available to lower-resourced adversaries, it is not always the case: police departments in large cities may have access to nation-state-level resources (e.g., through data sharing that is facilitated by fusion centers), or a particularly skilled neighborhood Nazi may possess advanced hacking skills that enable some corporate-level attacks.

So while these categories are not sharply defined, they can act as a starting point for understanding the risks and focusing on your adversaries’ most likely strategies and your most likely weaknesses.

Surveillance Strategies

There are two broad strategies of surveillance: mass-surveillance and targeted surveillance.

Mass surveillance collects information about whole populations. This can be done with the purpose of trying to better understand that population. For example, the collection and analysis of health-related data can help identify and monitor emerging outbreaks of illnesses. Mass surveillance may also be used as a strategy to identify individuals of interest within the surveilled population. For example, video feeds from security cameras can be used to identify those who engaged in property damage. Or mass surveillance may garner information about a particular individual. For example, information collected from the mass deployment of license-plate cameras can be used to track the movements of that particular individual.

Targeted surveillance only collects information about an individual or a small group of individuals. For example, wiretapping intercepts the communications of a particular individual. Targeted surveillance allows for the existence of prior suspicion and can (conceivably) be controlled—for example, law enforcement obtaining a warrant based on probable cause before intercepting someone’s mail.

Historically, there was a clearer divide between targeted and mass surveillance. However, in the digital age, many tactics of targeted surveillance can be deployed on a mass scale, as we will discuss further. In addition to this classic division of surveillance strategies, we draw attention to a bigger strategy that is unique to the digital age.

Collect-it-all may simply be viewed as mass surveillance on steroids but goes far beyond what may have historically been viewed as mass surveillance. Where mass surveillance may encompass things like security cameras, the monitoring of bank transactions, and the scanning of emails, collect-it-all aims to vacuum up any information that is digitized. Collect-it-all goes further: for any information that isn’t online or available (e.g., video from truly closed-circuit security cameras), it digitizes it and then collects it. Collect-it-all is infamously attributed to General Keith Alexander, former director of the NSA, whose mass-surveillance strategies were born in post-9/11 Iraq and were described as follows: “Rather than look for a single needle in the haystack, his approach was, ‘Let’s collect the whole haystack. Collect it all, tag it, store it… And whatever it is you want, you go searching for it.” This is likely the inspiration for many of the NSA programs that were uncovered by Edward Snowden that we highlight below.

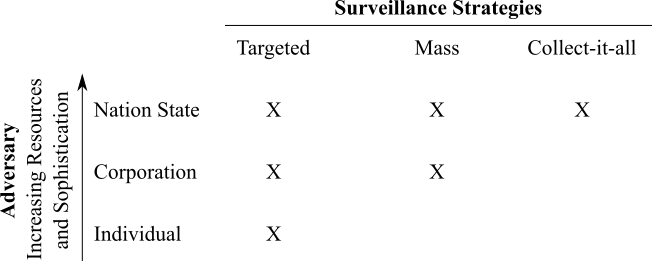

Different adversaries tend to deploy different surveillance strategies, or rather, lower-resourced adversaries tend to be limited in their strategies, as depicted:

Surveillance Tactics

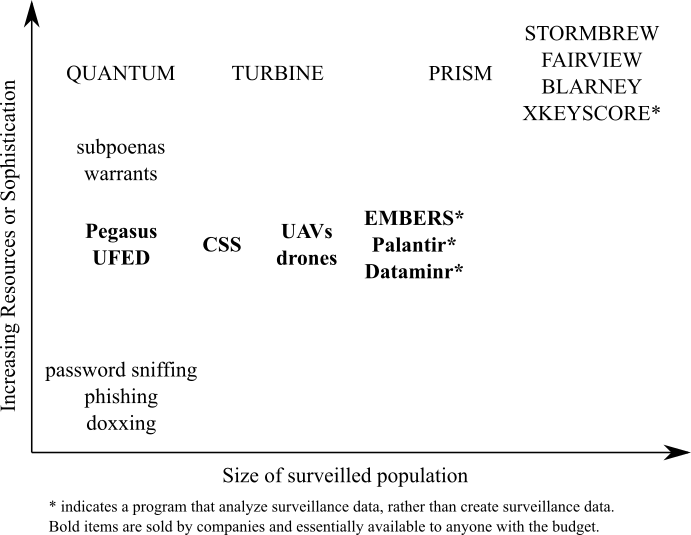

To go over all the surveillance tactics that are available to adversaries at all levels would fill an encyclopedia. Here we illustrate a few examples of surveillance programs and tactics that support the surveillance strategies above. We illustrate these programs (below) according to the minimum level of sophistication required to use the tactic and the number of people whose information would be collected via these means.

Mass Interception and Collection of Data

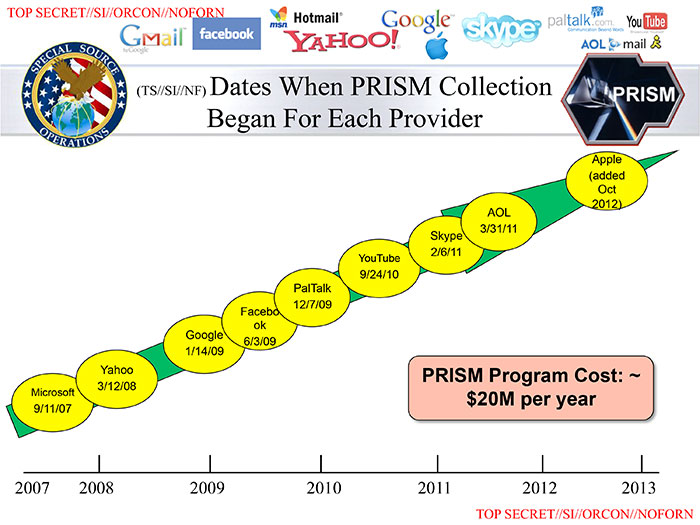

We start with what most people probably think of when they think of mass surveillance: the interception and possible recording of vast amounts of communications. Many mass interception programs were uncovered as part of Edward Snowden’s disclosures in 2013. STORMBREW, FAIRVIEW, and BLARNEY are three such programs through which the NSA collects data in transit by partnering with telecommunications companies and getting access to data passing through submarine data cables. This allows for the collection of any unencrypted content and all associated metadata while it is in transit from origin to destination. However, these programs cannot see content that is typically encrypted in transit, such as email or files in cloud storage. The PRISM program is a partnership of the NSA with various internet companies (such as Google, Microsoft, and Facebook, as illustrated below) to allow NSA access to data held on company servers. That is, if the information was encrypted in transit and so not collectible via STORMBREW, FAIRVIEW, and BLARNEY, then the NSA can get it via PRISM—unless the information is encrypted on the company servers with a key that the user controls.

Aggregating and Analyzing Data

Once you have a whole lot of surveillance data, what do you do with it? Surely the man will not be able to find my tiny little needle in that massive haystack. This is where data mining, from basic search to (creepy) predictive machine-learning models, comes in to make vast amounts of mass-surveillance data (including from disparate sources) useful to powerful adversaries.

The most basic functionality is the ability to search—that is, given a large amount of data, retrieving the data of interest, such as that related to a particular person. XKEYSCORE acts as a Google-type search for the NSA’s mass-surveillance data stores. While the functionality is basic, the sheer amount of information it has access to (including that from the NSA programs highlighted above) places XKEYSCORE (and any related program) as accessible to only the most powerful adversary.

On the other hand, Dataminr searches publicly available data (such as social media posts) to uncover and provide details of emerging crises (such as COVID-19 updates and George Floyd protests) to their customers, which include newsrooms, police departments, and governments, through both automated (software) and manual (human analysis) means. Dataminr and other social media–monitoring platforms, of which there are dozens if not hundreds, have come under fire for their surveillance of First Amendment–protected speech, most notably of the Movement for Black Lives. In several instances, Twitter and Facebook cut off social media–monitoring companies’ easy access to their data after public outcry over misuse.

Going further, Palantir is one of many policing platforms that supposedly predict where policing is needed, be that a street intersection, a neighborhood, or an individual. In reality, these platforms do little but reinforce racist norms. Predictive policing platforms use current police data as the starting point and tend to send police to locations that police have been in the past. However, communities of color and impoverished neighborhoods are notably overpoliced, so predictive models will simply send police to these areas again, whether or not that is where crimes are being committed.

Going further still, EMBERS (Early Model Based Event Recognition Using Surrogates) has been used since 2012 to predict “civil unrest events such as protests, strikes, and ‘occupy’ events” in “multiple regions of the world” by “detect[ing] ongoing organizational activity and generat[ing] warnings accordingly.” The warnings are entirely automatic and can predict “the when of the protest as well as where of the protest (down to a city level granularity)” with 9.76 days of lead time on average. It relies entirely on publicly available data, such as social media posts, news stories, food prices, and currency exchange rates.

Targeted Collection of Data

Another surveillance tactic that comes to mind is that of the wiretap. However, the modern equivalent is a lot easier to enable than the physical wire installed on a communication cable, from which wiretap gets its name. One modern version is the cell site simulator (CSS), which is a miniature cell tower (small enough to be mounted on a van). To cell phones in the vicinity, this tower provides the best signal strength, and so they will connect to it. At the most basic level, a CSS will uncover the identities of the phones in the area. (Imagine its use at the location of a protest.) Different CSSes have different capabilities: Some CSSes simply pass on the communications to and from the broader cell network while gaining access to metadata. In some cases, CSSes are able to downgrade service—for example, from 3G to GSM—removing in-transit encryption of cell communications with the service provider and giving access to message content. In other cases, CSSes can block cell communications by having phones connect to it but do not pass information onto the greater cell phone network. CSSes are fairly commonly held by law enforcement agencies (as illustrated in the map at the start of this chapter).

Surveillance equipment, including CSSes and high-resolution video, can also be mounted to surveillance drones or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which can greatly increase the scope of surveillance from a few city blocks to a whole city. This is one example where tactics of targeted surveillance are expanded toward a mass level. Persistent Surveillance Systems has pitched the use of UAVs to many US police departments. Persistent Surveillance’s UAV uses ultrahigh resolution cameras that cover over thirty-two-mile square miles in order to be able to track the movements of individual cars and people, saving a history so that movements can be tracked backward in time.

Of course, often it isn’t necessary to surreptitiously collect information. Sometimes you can just ask politely for it. In the US, subpoenas and warrants are used to request information from corporate providers. While warrants require probable cause (in the legal sense), subpoenas do not. As it publishes in its transparency report, Google receives around forty thousand data requests every year, about a third of which are by subpoena. Google returns data for roughly 80 percent of requests, and each request impacts, on average, roughly two user accounts (i.e., each individual request is highly targeted). Of note is that the contents of emails are available by subpoena. While subpoenas and warrants are basic in their nature, they usually can only be accessed by governmental adversaries.

Attacking Devices

The above tactics attempt to collect data while it is in transit or when it is held in the cloud. A final place to collect your data is right from your own device (phone or computer). This might happen if your device is confiscated by the police during a detention or search. We will discuss this more in the chapter “Protecting Your Devices,” but we highlight some tactics for extracting device-held data here.

Cellebrite is an Israeli company that specializes in selling tools for extracting data from phones and other devices, such as their Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED), which is small enough to carry in a briefcase and can extract data quickly from almost any phone. However, this requires physical control of your device. NSO Group (another Israeli company) sells the ability to remotely install spyware called Pegasus on some iPhones and Androids that will extract text messages, call metadata, and passwords, among other data. The NSA has a family of malware (malicious software) denoted QUANTUM that can either gather data or block data from reaching the target device. But the NSA is able to install this malicious software on a mass scale with the use of their TURBINE system, which is able to disguise NSA servers as, for example, Facebook servers and use this as a means to injecting malware onto the target’s device.

While Pegasus and QUANTUM can be deployed widely, it can be politically dangerous to do so, as these programs are generally met with public outcry. The more widely an invasive surveillance technology is deployed, the more likely it is to be discovered, as was the case with Pegasus.

Personalized Harassment

While outside the realm of typical surveillance, personalized harassment should be in mind when considering digital security risks. Doxxing, phishing, and password sniffing are techniques available to the lower-resourced adversary but shouldn’t be ignored for that reason. You may wish to revisit the story of Black Lives Matter activist DeRay Mckesson from the chapter “Passwords,” who had his Twitter account compromised despite employing two-factor authentication. All his adversary needed was access to some personal information, which may have been discoverable from public sources or through personal knowledge.

Doxxing is the process of publishing (e.g., on a discussion site) a target’s personal information that might lead to the harm or embarrassment of the targeted individual. While this is very easy to do, it is also very difficult to protect yourself: once information about you is available online, it is challenging or impossible to remove it.

Phishing describes methods of obtaining personal information, such as a password, through spoofed emails and websites. While phishing can be deployed on a mass scale, the most successful type of phishing (spear phishing) targets individuals by using already known information to improve success rates.

Password sniffing can be as low tech as looking over your shoulder to see you type in a password or can involve installing a keystroke logger to record you typing in your password, but this requires the ability to install a keystroke logger on your device, for which there are methods of varying degrees of sophistication. Traditional password sniffing captures a password as it passes through the network, which can be possible if the traffic is not encrypted, and again requires varying degrees of sophistication but certainly could be deployed by a skilled individual.

In Context: Standing Rock

In 2016, opponents of the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) set up a protest encampment at the confluence of the Missouri and Cannonball Rivers, under which the proposed oil pipeline was set to be built. The pipeline threatened the quality of the drinking water in the area, which included many Native American communities, including the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. Eventually the protest encampment would grow to thousands of people and was in place for ten months.

Energy Transfer Partners, the company building DAPL, employs a private security force, which, a few months into the protest encampment, unleashed attack dogs on the protesters. In addition, Energy Transfer Partners very quickly hired TigerSwan to aid in their suppression of the protest movement. TigerSwan is a private mercenary company that got its start in Afghanistan as a US government contractor during the war on terror. As such, TigerSwan employs military-style counterterrorism tactics and referred to the Native American protesters and others who supported them as insurgents, comparing them (explicitly) to the jihadist fighters against which TigerSwan got its start. TigerSwan’s surveillance included social media monitoring, aerial video recording, radio eavesdropping, and the use of infiltrators and informants.

Eventually local, regional, and federal law enforcement would be called in, with TigerSwan providing situation reports to state and local law enforcement and in regular communication with the FBI, the US Department of Homeland Security, the US Justice Department, the US Marshals Service, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. While many (but not all) of the tactics employed by TigerSwan would be illegal for government law enforcement to adopt, the State is able to skirt this by receiving updates from private companies. This is common practice in many areas in law enforcement, with police departments buying privately held data that would violate the Fourth Amendment if the data was collected directly by the State.

The public-private partnership between state law enforcement agencies, Energy Transfer Partners, and TigerSwan was instrumental in bringing an end to the protest encampment, with the State eventually violently removing protesters through the use of tear gas, concussion grenades, and water cannons (in below-freezing weather), resulting in approximately three hundred injured protestors (including one woman who nearly lost an arm).

While the encampment ended and the pipeline eventually was built, continued opposition eventually led to a court ruling that the pipeline must be shut down and emptied of oil in order to complete a new environmental impact review.

It is important to remember that even though mass surveillance collects information about almost everyone, the harm it causes is differential. Certain groups are surveilled more heavily, or surveillance information about certain groups is used disproportionately. Examples of groups in the US that are disproportionately harmed by State and corporate surveillance are Muslim Americans, Black and African Americans, Native Americans, and social movement participants, as we discussed in the chapter “Mechanisms of Social Movement Suppression.”

What to Learn Next

We encourage you, after this rather dismal account of all the ways your data can be swept up, to immediately start reading the chapter “Defending against Surveillance and Suppression.”

External Resources

- Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Atlas of Surveillance.” Accessed February 9, 2021.

- Department of Homeland Security. “Fusion Centers.” Accessed February 9, 2021.

- Google. “Transparency Report.” Accessed February 9, 2021.

- Nakashima, Ellen, and Joby Warrick. “For NSA Chief, Terrorist Threat Drives Passion to ‘Collect It All.’” Washington Post, July 14, 2013.

- Greenwald, Glenn. No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA and the Surveillance State. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2015.

- N, Yomna. “Gotta Catch ’Em All: Understanding How IMSI-Catchers Exploit Cell Networks.” Electronic Frontier Foundation, June 28, 2019.

- Stanley, Jay. “ACLU Lawsuit over Baltimore Spy Planes Sets Up Historic Surveillance Battle.” American Civil Liberties Union, April 9, 2020.

- Biddle, Sam. “Police Surveilled George Floyd Protests with Help from Twitter-Affiliated Startup Dataminr.” Intercept, July 9, 2020.

- Ahmed, Maha. “Aided by Palantir, the LAPD Uses Predictive Policing to Monitor Specific People and Neighborhoods.” Intercept, May 11, 2018.

- Muthiah, Sathappan, Anil Vullikanti, Achla Marathe, Kristen Summers, Graham Katz, Andy Doyle, Jaime Arredondo, et al. “EMBERS at 4 Years: Experiences Operating an Open Source Indicators Forecasting System.” In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining—KDD ’16, 205–14. San Francisco: ACM, 2016.

- Boot, Max. “Opinion: An Israeli Tech Firm Is Selling Spy Software to Dictators, Betraying the Country’s Ideals.” Washington Post, December 5, 2018.

- Intercept. “Oil and Water.” 2016–17.

- Fortin, Jacey, and Lisa Friedman. “Dakota Access Pipeline to Shut Down Pending Review, Federal Judge Rules.” New York Times, July 6, 2020.

Media Attributions

- atlas-of-surveillance © Electronic Frontier Foundation is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- surveillance-strategies © OSU OERU is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- prism_slide_5 © JSvEIHmpPE is licensed under a Public Domain license

- surveillance-tactics © OSU OERU is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license