Authenticity through Cryptographic Signing

What You’ll Learn

- How to achieve the digital equivalent of a signature

- How cryptographic signatures can be used to provide authenticity

- What electronic authenticity means

- How cryptographic signatures can be used to propagate trust

Public-key cryptographic systems can often be used to provide authenticity. In PGP, this is allowed by the complementary nature of the public and private keys. In the beginning, two cryptographic keys are created, and either can be used as the public key; the choice as to which is the public key is really just an arbitrary assignment. That is, either key can be used for encryption as long as the other one is used for decryption (and the one used for decryption is kept private to provide security).

Once you have assigned one cryptographic key as the public key and the other cryptographic key as the private key, you could still choose to encrypt a message with your private key. However, then anyone with your public key could decrypt the message. If you make your public key, well, public, then anyone could decrypt your message, and so this would defeat the purpose of using encryption to achieve message privacy.

However, this should illustrate to you that the only person who could have encrypted a message that can be decrypted with your public key is you, the person with your private key. Encrypting a message with your private key provides the digital equivalent of a signature and is called cryptographic signing. In fact, cryptographic signing provides two properties of authenticity:

- Attribution. You wrote the message (and not someone else).

- Integrity. The message is received as it was written—that is, it has not been altered.

The second property comes from the fact that a tamperer would have to alter the ciphertext such that decrypting the ciphertext with your public key generates the tamperer’s desired altered plaintext. But this is completely infeasible.

These properties are only meaningful if you are the only one who controls your private key, since anyone who gains control of your private key could cryptographically sign their own altered text.

Cryptographically Signing Cryptographic Hashes

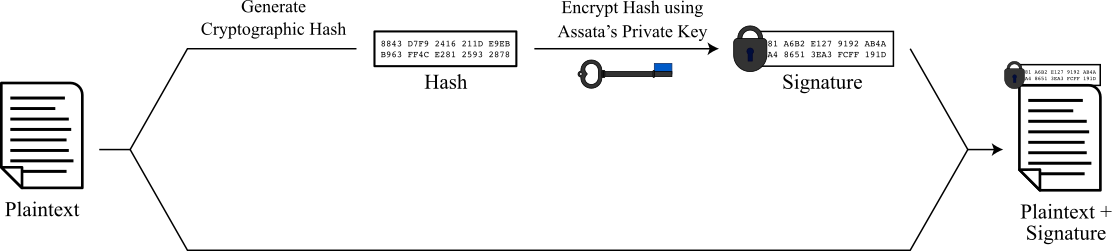

In practice, rather than encrypting the entire message, one would encrypt a cryptographic hash (a.k.a. digest or fingerprint) of the message for the purpose of cryptographic signing. This is done for efficiency reasons. Let’s consider the protocol for Assata signing a message and Bobby verifying the signature, as illustrated in the following text.

Assata takes a cryptographic hash of her message and encrypts the result with her private key, creating a signature, which she can attach to the message:

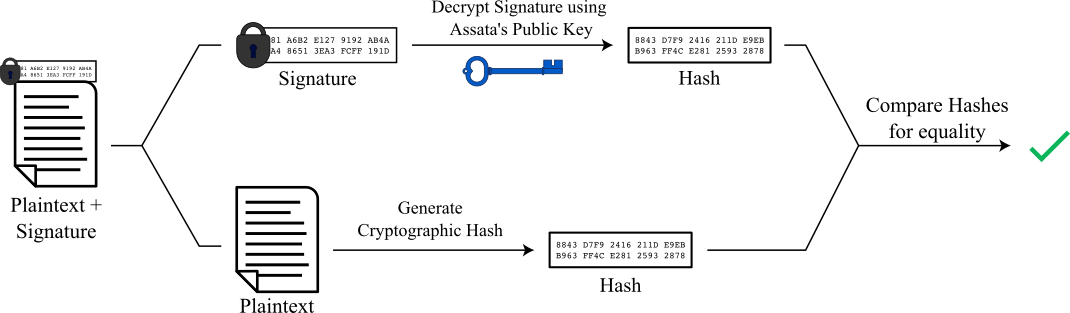

Bobby takes the signature and decrypts it using Assata’s public key, giving the hash that is the same as what Assata generated. He then takes his own cryptographic hash of the message and compares the result to the decrypted hash he received from Assata:

Recall that cryptographic hash functions are infeasible to counterfeit. So if the two hashes that Bobby generates (one directly from Assata’s message and one from Assata’s signature) are the same, then we know two things:

- Only Assata could have generated the signature. Only Assata could encrypt something that can be decrypted with her public key, since she is the only one with her private key.

- The message has not been altered since Assata wrote it. If someone altered the message, then the hash of the message would differ from the hash contained in the signature. Any counterfeiter would therefore have to forge a new signature but can’t generate one without Assata’s private key.

That is, we obtain authenticity cryptographically.

Note that Edgar, in a man-in-the-middle attack, could simply remove the signature. So for cryptographic signing to be effective, you need to agree to use cryptographic signing all the time. Modern end-to-end encrypted messaging apps generally have signing built in by default, though this is often invisible to the average user.

Applications of Cryptographic Signing

As in our example above, cryptographic signing can provide authenticity to messages in a similar way that traditional handwritten signatures and wax seals did. However, you can cryptographically sign more than just messages (such as emails).

Verifying Software

Perhaps the most explicit and common use of cryptographic signatures is for verifying software, even if you aren’t aware of it. Software such as apps will only do what their developers want and say they will do if they haven’t been tampered with on the way from the developer to your computer or phone. Responsible developers will sign their products in the same way as we described signing for messages. A program or app is really just a computer file (or set of files), which is just a sequence of characters or a type of message. If a developer has signed their software using public-key cryptography, a careful user can check the signature by getting the developer’s public key and performing the validation illustrated above. (The developer should provide their public key via a channel different from the one you downloaded the software from. This would allow an out-of-band comparison as described in the chapter “The Man in the Middle”—the public key, which you use for validation, is out of band from the message or software download.)

Managing Fingerprint Validation and the Web of Trust

To trust Assata’s public key, Bobby should really verify her public key by checking the fingerprint of the key, as we have described. Otherwise, Edgar, the interloper, could furnish Bobby with a public key that he holds the corresponding private key for. But if Bobby has verified that Assata’s public key is genuinely hers, Bobby can cryptographically sign Assata’s public key (with his own private key). This allows Bobby to keep track of the public keys that he has verified and allows him to share Assata’s key with other people as follows.

Suppose Cleaver wants to send Assata an encrypted message and wants to be sure that Edgar is not going to play the man in the middle. But Cleaver does not have a secondary channel through which to verify Assata’s public key. However, Cleaver has received and verified Bobby’s public key. So Bobby can send Assata’s public key to Cleaver with his signature. If Cleaver trusts Bobby and has verified his public key, then Cleaver can verify his signature on Assata’s public key and trust that Assata’s public key is genuine.

This is the basis of the web of trust. Rather than directly verifying fingerprints of keys, you can do so indirectly, as long as there is a path of trust between you and your desired correspondent.

In Context: Warrant Canaries

Warrant canaries or canary statements inform users that the provider has not, by the published date, been subject to legal or other processes that might put users at risk, such as data breaches, releasing encryption keys, or providing back doors into the system. If the statement is not updated according to a published schedule, users can infer that there has been a problem that may put their past or future data at risk. Riseup.net, for example, maintains a quarterly canary statement that is cryptographically signed so that you can ensure its authenticity—that is, that the people at riseup.net wrote the statement. They include a link to a news article dated on the day of release in their statement to give evidence that the statement was not published before the day of release.

The use of warrant canaries began as a way to circumvent gag orders in the US that accompany some legal processes in which the US government can force someone to withhold speech. On the other hand, the US government can rarely force someone to say something (particularly that isn’t true) and so could not compel a provider to keep up a canary statement that falsely claims nothing has happened.

The term originates from the use of canaries in coal mines to detect poisonous gases: if the canary dies, get to clean air quickly!

What to Learn Next

External Resources

- Riseup. “Canary Statement.” Accessed February 9, 2021.

- Tor Project. “How Can I Verify Tor Browser’s Signature?” Accessed February 9, 2021.

Media Attributions

- pgpsigning1 © OSU OERU is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- pgpsigning2 © OSU OERU is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license