Chapter 9: Courts

Introduction

When thinking about courts many of us think about the statute of “Blind Justice” – also known as Lady Justice – that adorns the front of many courthouses around the country. Often portrayed blindfolded and holding balance scales and a sword, the figure represented is Themis, the Greek Goddess of Justice and law. The blindfold she wears represents the impartiality with which justice is served, the scales represent the weighing of evidence on either side of a dispute brought to the court, and the sword signifies the power that is held by those making the ultimate decision arrived at after an impartial and fair hearing of evidence. In fact, in ancient Greece judges were considered servants of Themis, and they were referred to as “themistopolois.”

Whether or not state and local court systems in these modern times are providing blind justice as represented by the statute of Themis could be debated. While residents in communities around the country ideally hope their own court system is impartial and immune to outside influences, few who work in or participate in American state court systems believe this is fully true; in fact, there is evidence that suggests that protection from outside influences upon the courts is becoming less and less assured. Judges today are increasingly called upon to make tough public policy decisions, with the outcomes – some of which entail promoting sustainability – often being popular with some parties and unpopular with other parties engaged in a particular policy issue. Very often such decisions affect tradeoffs of economic, social and environmental goals, leaving some parties pleased and others anxious to “redress the balance” either in new statutory language or through further litigation in the courts. This continuation of the dispute through legal action often involves seeking out “more friendly courts” with more sympathetic judges in which to file their actions. Recall that most judges in the U.S. are elected officials who must campaign and remain sensitive to prevailing sentiments in the jurisdiction where they preside.

At the beginning of the American republic the Founding Fathers clearly believed that the judicial branch would be weak -- far weaker than either the Executive or the Legislative branches. In this regard, according to Alexander Hamilton (1788) writing in the Federalist Papers (number 78):

The Executive not only dispenses the honors, but also holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse, but also prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever.

Simply speaking, Hamilton thought the judicial branch, with its lack of command of either physical or financial resources, could never overpower the two other branches of government.

Contemporary state, county and municipal courts face many challenges, with some of these challenges placing an impact upon the provision of “Blind Justice” which society expects of its courts. They are beholden to executives and legislative bodies alike for the funding of the courts and the number of judges issuing rulings in civil and criminal cases alike. Despite the critical role of courts in state and local government, many citizens are unaware of the importance of their state and local court systems for the quality of life they experience.

This chapter will:

- explore the major aspects of state and local courts.

- discuss how these court systems operate.

- outline selection processes for the judiciary.

- introduce the topic of judicial federalism; including the challenges courts will face in the future.

- discuss the impacts courts have had and will have in the future with respect to the promotion of sustainability.

- discuss current trends in state supreme courts and local courts.

State Court Systems

Unlike other countries with a single, centralized judicial system the United States operates under a dual system of judicial power – one system of courts operates within each state’s constitution, and the other system of courts derives from the provisions of Article III of the United States Constitution. Thus, each individual state as well as the federal government are responsible for enforcing the laws, and state and local courts and federal courts adjudicate both civil and criminal case matters. It follows that Americans are dual citizens; not only are they citizens of the United States of America, but they are citizens of the state in which they reside as well.

With the exception of the appellate process, and possibly in the procedural realm of injunctive relief, the national and state courts are virtually separate and distinct entities. For example, since the U.S. Constitution gives the U.S. Congress authority to make uniform laws concerning bankruptcies, state courts largely lack jurisdiction in the matter. On the other hand, the U.S. Constitution does not give the federal government authority over the regulation of family life; in matters of family law (e.g., divorce, child custody, probate, division of property, etc.) a state court would have jurisdiction and a federal court would likely not hear cases (Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, 2024). While operating largely separately, the two systems can come together in the U.S. appellate courts (including the U.S. Supreme Court). The U.S. Supreme Court has final interpretative authority in the country with respect to disputes regarding the meaning of the U.S. Constitution and interpretation of its provisions by all “inferior” (i.e., subordinate) courts in the country. This situation of the coming together of the state and federal courts is a rather rare occurrence, and only happens when there is a substantial federal question of law and all remedies at the state level are fully exhausted. Even then, it is entirely left up to the U.S. Supreme Court to decide if it wishes to hear the case.

State courts were in place after the American Revolution, but with fresh memories of the Colonial Courts controlled as an extension of English rule Americans generally distrusted these early state courts (Glick et al., 1973). Since most states were predominantly rural in the distribution of their populations, conflicts between people tended to be relatively simple and were typically settled informally without the need of court intervention. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that modern unified state court systems emerged, with many of these “upgrades” in the procedures and practices of minor courts coming in response to the many new legal challenges arising from the industrial revolution. With industrialization, the American society was changing so rapidly in so many areas that state legislatures, most of which met for only brief periods of time, neither had the time nor the resources to develop statutes to cope with the rising problems. For example, with the advent of labor unions, patent rights and royalties associated with new technology, and complaints over growing corporate monopolies such as utilities and the railroads brought many disputes to the courts for resolution in the absence of governing statutes (Glickman et al., 1973). This set of circumstances resulted in many conflicts entering into state courts through parties asking the courts to use their common law “equity” powers to resolve contentious commercial, real estate, industrial insurance, and similar disputes born of a rapidly industrializing nation.

While general jurisdiction county courts were well established in American society and enjoyed growing legitimacy as the memories of colonial rule faded over time, these courts were neither adequately staffed nor properly organized to address the increasingly complicated problems of the day. When state and local courts became overwhelmed with litigation and lost faith in the legislative process to bring timely relief, the State Bar Associations (the professional licensing association of lawyers in a state) began to orchestrate reform in state court systems. This reformation depended on the separation of powers argument that empowered state supreme courts to create “unified” courts by mandate of the court as opposed to legislative action. More specifically, state supreme courts acted on their own authority as a separate branch of American government, establishing a system of courts wherein the state supreme court sits atop a system of interconnected courts, all of which adhere to the same rules and procedures on how all cases (criminal, civil and equity) are processed and appeals are made. In due course state legislatures codified the key elements of unified court operations into state statutory law. In virtually all of the states, this creation of unified court systems resulted in the addition of new jurisdictions, the development of uniform procedures, the common training of court personnel, and in many cases, the development of specialized courts such as small claims courts, juvenile courts, and family law courts.

Through the U.S. Constitution (Article 111, Sec. 1) the U.S. Congress has the power to establish “inferior courts” for hearing cases arising from federal law. As previously noted, the interaction between the federal and state courts is relatively rare, with the most notable exception being in the area of Civil Rights. Federal statutes such as the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act can, and have, brought federal and state court systems into close contact. As a general rule, state courts cannot interpret state constitutions in a way that undermines a U.S. Supreme Court ruling by condoning a less protective standard with respect to a civil right recognized to exist in the U.S. Constitution. On the other hand, state courts are permitted to interpret their state constitutions to require greater protections than those required by the federal courts.

Though federal and state court systems happily coexist in most respects, such mutual coexistence is not uniformly the case. For example, during the 1960s there was so much conflict between federal and state courts that a U.S. constitutional revision was proposed calling for the creation of the “Court of the Union,” a judicial tribunal which would have addressed the alleged encroachments upon state judicial power by the federal system (McGowan, 1967). Even though the “Court of the Union” idea ultimately failed to gain traction with either the public or the legal community, the conflict between the two systems that gave rise to the idea has not fully abated. An example of this conflict is the deep disagreement over capital punishment arising in late 2007.

While waiting for a U.S. Supreme Court decision as to whether the current method of lethal injection represents “cruel and unusual punishment,” a violation of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, many of the 36 states using lethal injection as a method of execution placed a de facto moratorium on executions. Other states boldly rebuked the U.S. Supreme Court and moved ahead with planned executions, despite the Supreme Court’s plea to await the outcome of its hearing of a key case. On November 2, 2007, barely a month after the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case [granted certiori] on lethal injection, the Florida Supreme Court unanimously ruled that their state's new method for carrying out lethal injections, after changes in the procedure were made which were prompted by a botched execution in December, do not violate the U.S. Constitution's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

How State Courts Work

Comparing one state court to another is like comparing apples to oranges in some respects. Some state court systems are extremely complex, while others are rather simple in their structure. For example, the state of New York, with a population of 19 million residents in the year 2024, are served by approximately 3,500 full time judges working within 13 different layers of courts. In contrast, California, with double the population of New York, has only three layers of courts and employs only 1,600 judges (Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, 2024). Even though both California and New York, and their respective local court systems, operate under the same general principles and under the structure of a unified court system, they do not operate in the same way. In order for attorneys to practice law in the state courts, they must be able to demonstrate knowledge of that particular state’s legal system by either passing the state bar examination or otherwise demonstrating sufficient command of the particular state’s system of courts. The caseloads for state courts vary widely, and these workloads seem to have little to do with the size of the state’s population. Generally speaking, western states’ courts, which were formed later in the nation’s history, tend to be more modern and simplified when compared to those of longstanding operation in the eastern states.

The organization of state and local courts tends to reflect two major influences: 1) the organizational model set by the federal courts; and 2) each state’s judicial preferences as manifested in state constitutions and judiciary statutes (Edwards et al., 1998). The increased influence of states’ constitutions within their judicial system, particularly in regards to civil rights, is known as judicial federalism. As the chapter on State Constitutions noted, Judicial Federalism is at play when state courts address the state’s constitutional claims first, and only consider federal constitutional claims when extant cases cannot be resolved solely upon state grounds.

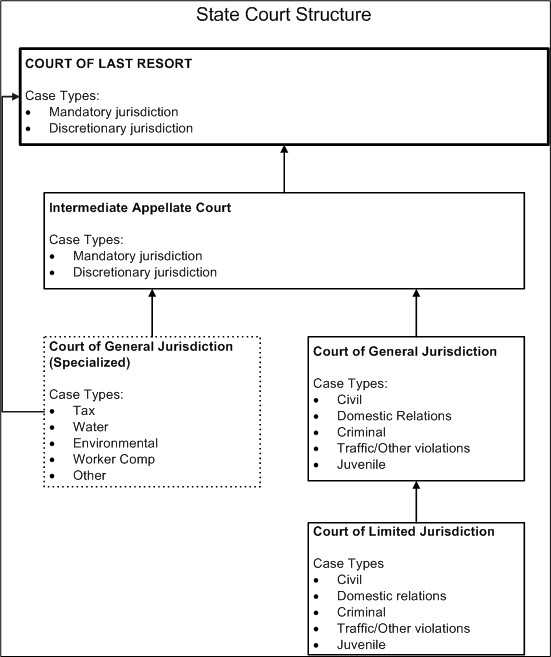

The legal terminology and structure of each state’s court are quite diverse, but they all follow a generic three-tiered structure. At the base is a system of general and limited jurisdiction trial courts of original jurisdiction (courts “of record”), with an intermediate set of appellate courts in the middle, and, at the top, the Court of Last Resort (also an appellate court). In addition, many states are increasingly using specialized, sometimes known as problem-solving, courts as needed. The fundamental distinction between trial courts and appellate courts is that trial courts are those of first instance that decide a dispute by examining the facts. Appellate courts review the trial court’s application of the law with respect to the facts as recorded in the official proceedings of the case in question (Rottman and Strickland, 2006). Figure 9.1 reflects how a generic three-tiered court system with a specialized court may operate. Some states’ court structure, usually those with small populations, may be more simplified than the generic system, while in some cases the states’ structure is more complex than the diagram implies.

Trial Courts: Trial courts often don’t garner the attention of either states’ higher courts or the federal courts, but they represent the veritable workhorses of the court system. Typically, each state has two types of trial courts of original jurisdiction, one of limited jurisdiction and one of general jurisdiction. Funding for trial courts of general jurisdiction generally comes from a combination of state and local sources. In most states, courts of limited jurisdiction are principally funded by local governments (counties and municipalities).

Trial courts of limited jurisdiction, as the name suggests, deal with specific types of cases and are often presided over by a single judge operating without a jury. Found in all but six states, courts of this type typically hold preliminary hearings in felony cases and exercise exclusive jurisdiction over misdemeanor and ordinance violation cases (Rottman and Strickland, 2006). Geographically, the jurisdiction of these courts varies across the states, but by-and-large they possess either a countywide jurisdiction or serve a specific local government such as a city or town. If there were an entity we could call a “community court,” it would be these courts. They are located within or near a community, and handle cases arising from misdemeanor offenses and ordinance violations. The courts of this type include, but are not limited to the following:

- Probate Court: Handles matters concerning administering the estate of a person who has died.

- Family Court: Handles matters concerning adoption, annulments, divorce, alimony, custody, child support, and other family matters.

- Traffic Court: Regarding cases involving minor traffic violations.

- Juvenile Court: Handles cases involving delinquent children under a certain age (generally under 21).

- Municipal Court: This court handles cases involving offenses against city ordinances (e.g., leash law violation).

General jurisdiction trial courts are the main trial courts in the state system, and in most cases, the highest trial court. These courts are generally divided into circuits or districts. In some cases, the county serves as the judicial district, but in most states a judicial district embraces a number of counties, which is why they are often referred to as circuit courts. General jurisdiction trial courts hear cases outside the jurisdiction of the limited jurisdiction trial courts, such as felony criminal cases and high stakes civil suits. In most states cases are heard in front of a single judge, often with a jury.

Intermediate Appellate Court: Intermediate Appellate Courts go by many names, including Superior Court, Appellate Division, Court of Appeals, and even Supreme Court. With the exception of 11 states, which usually have small populations, states have some form of intermediate appellate courts. The main role of these courts is to hear appeals from trial courts. Any party, except in a case where a defendant in a criminal trial has been found not guilty, who is not satisfied with the outcome from the trial court may appeal to an intermediate appellate court. States’ intermediate appellate courts are structured in a variety of ways, but typically they are regionally based and divided into “divisions,” “courts” or “districts.” For example, Florida has five District Courts of Appeal while more sparsely populated Idaho has a single Court of Appeals. The courts are usually set up with the judges working in panels of three or more (always an odd number), and the majority of judges decides the outcome of the cases brought to the court. The appellate courts do not have juries, do not hear from witnesses or review the facts of the case, but instead read briefs and hear arguments from the parties’ attorneys to decide issues of law or process raised in the cases brought up on appeal. The majority of the time its decisions are final, but it is possible to appeal to the next appellate court level, often the Court of Last Resort.

Court of Last Resort: All states have a Court of Last Resort, primarily referred to as the Supreme Court, which acts as the state’s highest appellate court. In fact, two American states -- Oklahoma and Texas -- have two Courts of Last Resort; one represents a conventional Supreme Court and the second constitutes a Criminal Court of Appeals. The most common arrangement, found in 28 states, is a seven-judge court; 16 states have five Supreme Court justices, while five states have nine judges (Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, 2024).

With the exception of the 11 states that don’t have an intermediate court of appeals, the Courts of Last Resort have discretion as to whether or not they will hear a case. As an appellate court, it hears cases without a jury, focusing on major questions of law and constitutional issues. Many Courts of Last Resort do have original jurisdiction in certain specific matters, such as the reapportioning of legislative districts. The decisions coming from these courts are final, with the extremely rare exception of when the U.S. Supreme Court decides to hear an appeal from a state.

There are two ways a case regarding a state can be heard in the U.S. Supreme Court. The first, and almost nonexistent, is with the U.S. Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction, which involve cases between the United States and a state, between two or more states, and between a state and a foreign country. These cases typically go through the federal system, therefore rarely involve a decision from a state court. The second path for a state-based case is through the U.S. Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction. In these instances, the U.S. Supreme Court can choose to hear a case appealed from a state’s Court of Last Resort. In order for this to occur there must be a substantial federal question involved and the case must be viewed as “ripe,” meaning the petitioner has exhausted all potential remedies in the state court system and the resolution of the case can set a useful precedent for the future resolution of similar cases.

The Fifth Amendment case of Dolan v. City of Tigard serves as a good example of such a case. This case centered on municipal zoning regulations and property rights. Dolan, an owner of a plumbing supplies store, appealed her claim to the Oregon court system where the Oregon Supreme Court found for the City and rejected the argument that an unconstitutional taking of private property by government without just compensation occurred as a result of a zoning decision made by the city. As the case involved Fifth Amendment constitutional rights, the federal courts determined that this case raised a question of federal law. Given that essential determination, Dolan was able to appeal her case to the federal courts, and ultimately all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court found in favor of Dolan, causing local governments across the country to take notice of new requirements for determining just compensation in similar cases.

Problem Solving Courts: Problem-solving courts commonly referred to as “specialized courts” dispensing “therapeutic jurisprudence,” have emerged in most American states over the past decade. Problem solving courts relieve overwhelmed legal systems dealing with persons and families whose actions stem from problems better dealt with by “supervised treatment” rather than incarceration or similar forms of punitive governmental sanctions. These courts represent an attempt to craft new, adaptive responses to chronic social, human and legal problems that are resistant to conventional solutions associated with the adversarial process (Bermann and Feinblatt, 2002).

Though lacking a precise definition or legal philosophy, problem solving courts share a basic theme: a desire to improve the results that courts achieve for victims, litigants, defendants, and communities through a collaborative process rather than the conventional adversarial process (Bermann and Feinblatt, 2002). Traditional courts tend to focus on the determining guilt or innocence, entail looking backward in time, and are conducted in an adversarial way. In comparison, specialized courts focus on the identification of therapeutic interventions, seek to affect future outcomes, make use of a collaborative process, and involve a wide range of court-based and community-based services and stakeholders (Bermann and Feinblatt, 2002).

A number of factors that have led to the rise of special courts, including prison (state facilities) and jail (county and city facilities) overcrowding, highly stressed social and community institutions, and increased awareness of social issues such as domestic violence. While increased social awareness has indeed played some role in the development of these specialized courts, the lack of resources available to state and local court systems has been the major driver behind the broadening use of such courts; the caseloads of the courts have increased substantially in recent decades while the resources available to the courts have not increased proportionately. Recent data on domestic violence cases in U.S. state courts indicate that the trends have varied, with some states experiencing increases in incidents. For example, in New York, domestic violence victim counts rose in both the New York City metropolitan area (an increase of approximately 12% from 2021) and the rest of the state (an increase of about 2%) (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2023). Nationally, a study by the Council on Criminal Justice found that domestic violence cases in the U.S. increased by about 8% following the implementation of pandemic-related lockdown orders in 2020. This chapter synthesizes findings from multiple U.S. and international sources, suggesting that the isolation and economic stresses brought on by the pandemic likely exacerbated the factors that contribute to domestic violence (Council on Criminal Justice, 2024).

Problem solving courts got their start in 1989 when Dade County, Florida experimented with a “drug court.” The drug court, in an attempt to address the problem of criminal recidivism (re-offense) among illegal drug use offenders, sentenced such repeat offenders to a long-term, judicially supervised drug treatment instead of incarceration. In reflection of Dade County’s success with this alternative to incarceration, drug courts taking a similar approach to drug use offenders began to crop up all over the United States. As of the latest data available in 2022, there are 1,834 Adult Drug Courts operating in the United States. This number represents an increase of 8% from the count in 2019, which was 1,697 Adult Drug Courts. These courts play a critical role in managing cases involving substance use by providing judicial supervision along with health treatment services instead of traditional incarceration (National Criminal Justice Reference Service, 2022).

Since this development in 1989, a variety of specialized courts have emerged, primarily designed to tackle difficult social issues. For example, New York City opened its Midtown Community Court in 1993 to target misdemeanor “quality-of-life” crimes, such as prostitution and shoplifting. Instead of relying upon traditional sentencing involving incarceration, offenders were required to pay back the community for the harm they caused by community service work such as cleaning local parks, sweeping streets, and painting over graffiti. In addition, to address the underlying cause of the problem behavior, the offenders were mandated by the court to receive “therapeutic” social services, such as counseling, anger management instruction, substance abuse treatment, and/or job training (Bermann and Feinblatt, 2002). Typically, elements of the local community are also engaged in the work of the problem solving courts by participating on advisory panels, providing volunteer services, and taking part in town hall meetings. The City of Portland, Oregon, for example, opened a number of “Community Courts” throughout the city, in many cases holding court at existing local community centers.

Evidence collected in evaluation studies conducted on many drug courts indicates that these problem solving courts tend to achieve favorable results with regards to keeping offenders in treatment, reducing their drug use, reducing recidivism, and economizing on jail and prison costs. The retention rates in drug courts significantly outperform those in voluntary programs. Typically, drug courts see a retention rate of about 60%, which is notably higher compared to the 10-30% retention rates observed in voluntary treatment programs. This higher retention rate in drug courts can be attributed to the structured nature of the programs, which often include close monitoring and support, coupled with judicial oversight, providing a more integrated and supervised approach to treatment (National Institute of Justice, 2020).

Moreover, drug court participants have far lower re-arrest rates than do persons taken into the traditional court process (National Institute of Justice, 2020). Additionally, a comprehensive study conducted in 2011 by the National Institute of Justice confirmed the effectiveness of drug courts. This research demonstrated that participants in drug courts were less likely to fail drug tests or get rearrested compared to their counterparts not in the program. While drug courts may incur higher initial costs than standard legal processes, they ultimately provide significant financial benefits by reducing the rates of re-offense and subsequent incarcerations, saving an average of at least $5,680 per individual in the long term (National Institute of Justice, 2020).

The types of problem solving courts are many, but the majority of them fall into the categories of limited or general jurisdiction trial courts (courts of original jurisdiction). The most common specialized courts are those that work on social issues, primarily substance abuse and family courts. Some examples of specialized courts include: gun courts, gambling courts, homeless indigent courts, mental-health courts, teen courts, domestic violence courts, elder courts, veterans’ courts, and community courts involving lay citizens in the process of arranging for property crime offenders to engage in compensatory justice with respect to those whom they have victimized.

Some states have taken it upon themselves to permit the establishment of specialized courts for the protection of the environment and for addressing the economic costs and benefits of pursuing sustainability. Such specialized courts have been created to deal with highly complex issues, which require extraordinary scientific and technical knowledge on the part of the court. Specialized environmental courts in the U.S., like Colorado's Water Courts, are designed to manage complex legal and factual issues around water rights. These courts employ judges with expertise in environmental law and often utilize special “court masters” for technical aspects of cases. Such courts illustrate how specialized judicial bodies can effectively handle specific types of legal disputes that involve intricate environmental regulations and scientific data.

In addition to the difficult adjudication of rival water rights claims, Colorado’s version of the Water Court has jurisdiction over the use and administration of water and all water matters within its statewide jurisdiction. Vermont has established an Environmental Court to hear matters on municipal and regional planning and development, to hear disputes over state solid waste ordinances, and to handle cases arising from the enforcement actions of the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources. As matters relating to global climate change and the more rigorous regulation of greenhouse gases arise, it is likely that more specialized courts will be created in other states to deal with the disputes arising from the active pursuit of sustainability in our states and local governments.

States are also developing specialized courts to manage economic disputes that arise in the course of commercial activity (such as business formation, business transactions, and the sale/purchase of business assets). Five states have established Tax Courts that deal exclusively with tax disputes. Montana, Nebraska, and Rhode Island developed specialized courts to deal exclusively with Workers’ Compensation cases. In many states, which do not have such specialized courts, there has been a steady trend in the growth of the number and range of activities of administrative law judges.

These “hearings officers” work within administrative agencies which engage in regulatory actions that give rise to many disputes (environmental regulations, labor/management actions under collective bargaining agreements, compensation for damages incurred from state government action on one’s property, eligibility appeals for benefit programs, etc.). These administrative law judges (ALJs) hold quasi-judicial hearings, carefully weigh the arguments of the agency and aggrieved citizens, and have the authority to mediate, arbitrate and ultimately decide upon an outcome to a case, which is binding on all parties. While such decisions made by ALJs can be appealed to the courts, state court judges seldom overturn their rulings. The federal government has similar processes in place under the provisions of the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946, and each state has enacted a comparable statute under which ALJs operate.

Judicial Selection

The manifest aim of the judicial selection process in the American states is to select a judiciary that is as impartial as the Greek Goddess Themis, but one that is at the same time accountable to the will of the people of the state. Unlike the federal judiciary where lifetime appointments are made to the federal district, circuit and supreme courts, in the states nearly all judges serve for fixed terms of office and most are subject to some method of retention in office based upon a vote of the people. Each state uses a system of selecting judges they feel is best suited to accomplish the dual goals of impartiality and accountability to the people. In most cases, a state’s judicial selection process does not catch the public’s attention given the limited knowledge citizens typically command regarding the courts and the actions of their judges; some particularly cynical observers have characterized judicial selection processes as being “about as exciting as a game of checkers…played by the mail” (Schultz, 2006).

There is no simple way to describe states with respect to their form of judicial selection system, because judges in different (or even the same levels of courts) within one state may be selected through different methods (Rottman and Strickland, 2006). A system to select a judge for the intermediate appellate court, for example, may be different than the system used for the Court of Last Resort, and different again from the system used for recruitment to the trial courts. Making things even more complex, the selection process for subsequent terms may be different than the initial term of office.

No single selection process – such as gubernatorial appointment, merit commission screening for gubernatorial appointment, non-partisan election, partisan election, legislative appointment, nomination to vacancies by county commissioners – currently dominates over other processes, nor do these selection processes within each state remain static over time. This includes both partisan (e.g., Pennsylvania and Louisiana) and non-partisan (Michigan and Arkansas) elections (Brennan Center for Justice, 2024). Non-partisan elections remain a significant method for judicial selection at various levels, including some states where partisan elections were previously more common (Kritzer, 2021). Worthy of note, the landscape of judicial elections has become increasingly politicized, with significant money flowing into these races, which raises concerns about the influence of special interests and the overall impartiality of judicial proceedings (Brennan Center for Justice, 2024). As with the U.S. Supreme Court, what were once largely nonpartisan processes of selection “on the basis of “judicial temperament” are increasingly political contests to seat judges of a liberal or conservative bent.

While there are many types of selection processes, four principal processes are used in the U.S. for judicial selection within the states: partisan election, non-partisan election, appointment, and the Merit System (known as the Missouri Plan). No one process dominates the others in extent of use, or in the level of controversy associated with its use. There are some regional differences in evidence where each type of judicial selection process tends to be concentrated. For example, some of the nation’s most conservative states, including Texas and states in the “Deep South,” use partisan elections principally, while many Midwest states tend to make use of the gubernatorial appointment process. Table 9.1 shows how each state selects its judiciary as of the present time

Table 9.1 Judicial Selection Method by State

| - | Court of Last Resort Name/s | Method of Selection | Intermediate Appellate Court/s | Appellate Court Justices | General Trial Courts | Method of Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Criminal Appeals | Partisan Election | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Court of Civil Appeals | Partisan Election | |||||

| Alaska*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Arizona*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Arkansas | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Elections | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | Chancery/Probate Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| California | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeal | Appointment | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Colorado*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Connecticut | Supreme Court | Appointment | Appellate Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Delaware | Supreme Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment | ||

| Court of Chancery | Apppointment | |||||

| Florida | Supreme Court | Appointment | District Court of Appeals | Appointment | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Georgia | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Hawaii | Supreme Court | Appointment | Intermediate Court of Appeals | Appointment | Circuit Court | Appointment |

| Idaho | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Illinois | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Appellate Court | Partisan Election* | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Indiana*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals Tax Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Partisan Election |

| Probate Court | ||||||

| Circuit Court | ||||||

| Iowa*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Kansas*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Kentucky | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election* | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Louisiana | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Appeal | Partisan Election* | District Court | Partisan Election |

| Maine | Supreme Judicial Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment | ||

| Maryland | Court of Appeals | Appointment | Court of Special Appeals | Appointment* | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Massachusetts | Supreme Judicial Court | Appointment | Appeals Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Michigan | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Minnesota | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Mississippi | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election* | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Missouri*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Montana | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | District Court | Appointment | ||

| Nebraska*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment** | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Nevada | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | District Court | Nonpartisan Election | ||

| New Hampshire | Supreme Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment | ||

| New Jersey | Supreme Court | Appointment | Appellate Division of Superior Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| New Mexico | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Appeals | Partisan Election | District Court | Partisan Election |

| New York | Supreme Court | Appointment | Appellate Division of Supreme Court | Appointment | Supreme Court | Partisan Election |

| Appellate Terms of Supreme Court | Appointment | County Court | Partisan Election | |||

| North Carolina | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election | ||

| North Dakota | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | District Court | Nonpartisan Election | ||

| Ohio | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Appeals | Partisan Election | Court of Common Pleas | Partisan Election |

| Oklahoma*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment* | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Criminal Court of Appeals | Appointment | |||||

| Oregon | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Tax Court | Nonpartisan Election | |||||

| Pennsylvania | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Superior Court | Partisan Election | Court of Common Pleas | Partisan Election |

| Commonwealth Court | Partisan Election | |||||

| Rhode Island | Supreme Court | Appointment | ||||

| South Carolina | Supreme Court | Appointment# | Court of Appeals | Appointment# | Circuit Court | Appointment |

| South Dakota | Supreme Court | Appointment | ||||

| Tennessee | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Partisan Election | Circuit Court | Appointment |

| Court of Criminal Appeals | Partisan Election | Criminal Court | Appointment | |||

| Chancery Court | Appointment | |||||

| Probate Court | Appointment | |||||

| Texas | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Appeal | Partisan Election | District Court | Partisan Election |

| Criminal Court of Appeals | Partisan Election | |||||

| Utah*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Vermont | Supreme Court | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment | ||

| District Court | Appointment | |||||

| Virginia | Supreme Court | Appointment# | Court of Appeals | Appointment# | Circuit Court | Appointment |

| Washington | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| West Virginia | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Circuit Court | Partisan Election | ||

| Wisconsin | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Wyoming*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

* Justices chosen by district

** Chief Justice chosen statewide, associate judges chosen by district

*** Uses of the Merit System for Judicial Selection

# Legislative Appointment

Partisan and Non-Partisan Elections: As of 2023, 38 states in the United States elect some or all of their judges. This practice is prevalent across various levels of the judiciary, including supreme courts, intermediate appellate courts, and trial courts. The methods of these elections vary, encompassing partisan elections, nonpartisan elections, and retention elections (Ballotpedia, 2023a). From this statistic alone it is clear that the goals of impartiality and public accountability are both important elements of state and local government judicial selection in the U.S. Alexander Hamilton (1788) spoke for the Founding Fathers in Federalist Paper No. 78 wherein he argued that if judges in federal courts were chosen by elected officials they would harbor “too great a disposition to consult popularity to justify a reliance that nothing would be consulted but the Constitution and the laws” (Hamilton, 1788). In 1939, well over a century after Hamilton’s warning, President William Howard Taft described judicial elections in the U.S. as “disgraceful, and so shocking…that they ought to be condemned” (Schotland, 2003).

Alexander Hamilton and former-President Taft may well be turning in their respective graves given the results of recent surveys. Survey results indicate that concerns about the impartiality of judges due to campaign contributions remain significant among Americans. For instance, a survey by James L. Gibson found that financial contributions to judicial campaigns are associated with lower perceived impartiality, particularly donations from attorneys (Gipson, 2021). The study highlighted a statistically significant relationship between the amount donated and a decline in impartiality ratings, emphasizing that such perceptions could potentially affect the judiciary's legitimacy (McClure, 2018). Another comprehensive study on "Judicial Impartiality, Campaign Contributions, and Recusals," published on OSF, further supports these findings, reflecting ongoing public concern about the impact of campaign contributions on judicial decisions and impartiality. This survey confirms that the dilemma of campaign financing in judicial elections continues to challenge the public’s trust in an unbiased legal system (Gipson, 2021).

Citizens are poorly informed about judges because, in most states, there are state supreme court-issued limits or guidelines, derived from the American Bar Association’s judicial canons (particularly Canon 7), as to what a judicial candidate can say or do while campaigning for judicial office. These limitations tend to be especially strict in states with non-partisan elections. For example, the Minnesota Code of Judicial Conduct Canon 5(A)(3)(d)(i) prohibits judicial candidates from announcing their views on disputed legal or political issues (Schultz, 2006). Yet there are a handful of states, such as Texas, where the judicial elections are highly partisan, extremely expensive, and vehemently contested and money is spent with the goal of seating judges with a particular conservative or liberal bent.

The practice of governors appointing judges just before the end of their terms, effectively bypassing elections, is observed in several states. This scenario commonly occurs under systems where the governor has the authority to fill judicial vacancies. This might happen due to a judge retiring or stepping down before their term ends. For example, states like New Jersey and Tennessee have seen such appointments influenced by political considerations, where governors appoint judges that align with their political ideologies or as part of political negotiations. These appointments can shift the balance of the court without an electoral process, thus raising concerns about political influence in judicial selection. Moreover, various states employ different methods for judicial selection, which may include gubernatorial appointments. This system is defended by some as a way to maintain judicial independence by insulating judges from the pressures of election campaigns and the influence of special interests. However, critics argue it can compromise public accountability and does not necessarily ensure that the most qualified or representative candidates are chosen for judicial offices. Ultimately, the method of judicial appointment and its implications can vary significantly from state-to-state, influenced by local legal traditions, political culture, and specific state constitutions or statutes (Ballotpedia, 2024; Ballotpedia, 2023b; Gordon, 2024).

Partisan elections are those in which judicial candidates, including incumbents, run in party primaries and are listed on the ballot as a candidate of a political party. In contrast, non-partisan elections are those in which the judicial candidates run on a ballot without a political party designation. There are a few cases where candidates are chosen in a party primary and backed by the party, but they appear without the party label on the ballot. The party affiliations of judges aren’t exactly the best kept secrets; judicial candidates often list a party affiliation in their official biographies, and political parties will often endorse particular judicial candidates. These endorsements normally are announced in local newspapers and letters to the editor submitted during election periods, and now are commonly disseminated through social media channels.

In comparing the two elective systems, each one has its own pros and cons. The proponents of partisan election tend to feel strongly that the party affiliation next to a judicial candidate’s name provides important information to voters with respect to the candidate’s likely political philosophy. The proponents counter that “justice is not partisan” – that is, there is no Democratic or Republican form of justice, only the impartial justice dispensed by the blindfolded Themis who is unaware of whether the parties coming before her are Democrats or Republicans. The proponents of partisan election counter that in the non-partisan judicial elections it is the voters who are blindfolded and unable to exercise popular accountability over judges as intended in the election process.

One additional drawback associated with partisan judicial elections is that they can lead to an imbalance among a state’s judiciary in cases where a state features strong one-party dominance. The State of Texas encountered this problem during the indictment of former House Majority Leader Tom Delay for corruption charges. Since Texas judges are elected on a partisan ticket, and often contribute openly to partisan causes, quite a scramble was necessary to identify an impartial trial judge who was acceptable to both the prosecution and defense in the Delay case (Rottman and Strickland, 2006).

Judicial Appointments and the Merit System: There are two common methods of judicial appointment, “simple” gubernatorial appointment and the “Merit System” of appointment. The simple gubernatorial appointment is much like that for federal judges, where the highest elected official (the President in the federal government and the Governor in the states) fill vacancies on the bench. How judges are selected by state governors depends on the governor in question and traditions in the state. Generally speaking, the background of the judge (former prosecutors, defense attorneys, type of pro bono work done, level of activity in local bar associations, etc.), the political needs of the governor (someone from a particular area of the state is needed to balance out an appellate bench), presence or absence of advocacy for particular persons by interest groups (women attorneys, minority attorneys, etc.), the views of leaders of the State Bar Association, and the preferences of the political parties are all more or less in play when state governors make their judicial appointments (Gordon, 2024).

The Merit System or Missouri Plan system for judicial appointment was designed to “take politics out of judicial selection” by combining the methods of appointment with election in a very particular way. Featuring three distinct components, it is the most complex of the judicial selection processes. Fourteen states use some version of the Missouri plan, with some additional states using a modified version of this type of selection process. Under the provisions of the Missouri Plan, candidates for judicial vacancies are first reviewed by an independent, bipartisan commission of both lawyers and prominent lay citizens. From a list of nominees submitted to the commission, three names are provided to the governor from which one person is selected to fill the vacancy on the bench in question. If the governor doesn’t pick one of the three persons put forward by the commission within sixty days, the commission is empowered to make the selection.

Once the judge selected by this process has been in office for one year or more, they must stand in a “retention election” during the next scheduled general election period. In such an election there is no opponent – voters are either voting to retain the judge in office or remove him or her from the judicial post in question. If there is a majority vote to remove the judge from office, the judge must step down and the process starts anew (Missouri Judicial Branch). By making the appointed judge stand for a retention election, the people over whom the judge exercises judicial authority have the ability to remove a judge they feel does not perform his or her duties well. Whether or not this was intentional on the plan of Missouri Plan designers, judicial removal is exceedingly rare; in the first 179 elections held under the Missouri Plan only one judge did not retain his position, and this was a case in which extraordinary circumstances were present (Gordon, 2024).

The term “merit” in the Missouri Plan judicial selection process implies that nominating commissions are disengaged from party politics, but the extent to which this disengagement is achieved depends in large measure on who selects the commissioners and how they carry out their duties. These two factors vary considerably across the states using the Missouri Plan. In a number of states, the governor has a major role in picking members of the commission, and in other states interest groups play a significant role, thereby to some extent circumventing of the “de-politicization” goal of the merit selection system.

The geographic basis for the selection of trial court and appellate judges is somewhat different for each state, and for each type of court within the state’s unified court system. For trial courts, a useful general rule of thumb is that judges are elected from within the jurisdiction over which they preside. For example, Montana’s Municipal courts are elected in a nonpartisan election within the city wherein the court operates, while the Water Court, which exercises statewide jurisdiction, is elected in a nonpartisan election from throughout the state. In the majority of states, thirty in all, levels of the state’s appellate courts are either elected or appointed statewide, while six states select all of their appellate justices by district or region.

When it comes to discussions concerning how judges should be selected, the most contentious debates occur on the question of how judges on the Courts of Last Resort should be selected. Even though they are appellate courts, and often use the same process for selecting the immediate appellate court judiciary, there are nonetheless noteworthy differences. The geographic basis for selecting a judge is usually statewide, although in eight states the Courts of Last Resort select judges via districts. This difference between district and statewide selection can be a source of considerable contention within states, particularly in those states with liberal urban centers and conservative rural areas. Terms of office for a judge on the Court of Last Resort ranges from a low of five years to a high of 14 years. There are three exceptions to the fixed term system of judicial appointment; Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island all appoint their justices until they reach the age of 70 or die in office. State supreme court terms vary across the United States. In most states, the term lengths are either six, eight, ten, or twelve years, though some states have unique arrangements:

- Six-Year Terms: States like Ohio and Nevada have six-year terms for their supreme court justices.

- Eight-Year Terms: States such as Michigan and North Carolina use eight-year terms.

- Ten-Year Terms: Wisconsin and Pennsylvania are examples of states where justices serve ten-year terms.

- Twelve-Year Terms: Missouri and Virginia have some of the longest terms, at twelve years.

Some states have provisions for justices to serve until a certain age. For instance, in New Jersey, justices initially serve a seven-year term and can be reappointed until they reach the age of 70. Naturally, the shorter the term of service, the more often a justice has to run in a retention election and must rely upon supporters to organize and finance their campaign.

An overarching question on judicial selection is this -- does the method of selection really matter or affect the way courts operate? Evidence suggests that different selection processes produce different results both in terms both of who tends to make it to the bench and in terms of rulings made. For example, Lovrich and Sheldon found that judicial selection systems that require judicial candidates to campaign actively in competitive elections result in judicial electorates (voters who participate in elections for judges) who are better informed than judicial selection systems which feature only retention elections (Lovrich and Sheldon, 1985). Similarly, it has been reported that appointed judges are likely to respond to a wider variety of groups and interests, and support individual rights more strongly in their rulings than elected judges (Schultz, 2006).

Courts – What Can I do?

- Find out more by visiting the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) website at https://www.ncsc.org/

- Consider visiting your local county or city court and watch the proceedings. Many court activities and trials are open to the public. Locate your local county or city court through the National Association of Counties website (http://www.naco.org/), the International City Managers Association (http://icma.org/), or the U.S. Courts website (http://www.uscourts.gov/courtlinks/).

State and Local Courts and Sustainability

The judicial branch may not “hold the sword” as does the executive branch, nor “command the purse” as does the legislative branch, but contrary to Alexander Hamilton’s view, it does have great influence over American society. In many areas of American life, the courts have fostered needed change when the “political branches” could not do so. In the areas of freedom of speech and peaceful demonstration of political protest, racial equality, business regulation, the rights of the accused, and environmental protection, the victories made along the way were often seen not in legislation, but rather in the American courts. State and local courts may be somewhat reluctant participants in the public policy process, but they do have a very important role as policy makers nonetheless. Judges are called upon to exercise judicial review of both the legislative and executive branches, interpret laws and constitutions, and make judicial policy. While unified state courts ensure a high level of consistency in the operation of courts, the decentralized operations of local courts make it possible for judges to become key actors in local political life by dealing with litigation reflecting local social, economic, environmental and political conflicts in impartial and constructive ways. Many of the decisions trial court judges make have the potential of establishing important policies affecting local practices in such important areas as zoning, public access to information, the provision of legal services to indigents, permissible policing practices, and equal access to education.

Cases heard in a local trial courts can have an important impact on sustainable development throughout the nation; the most recent such case is that of Kelo v. City of New London, Connecticut. The case in question, as with the Dolan case from Oregon discussed above, concerned Fifth Amendment rights set forth in the U.S. Constitution. The controversial issue arose when the City of New London chose to use its power of eminent domain to condemn some private homes so that the property on which they sat could be used as part of the city’s economic development plan; a plan would result in this private property being condemned for use by another private party working in concert with the City of New London. The homeowners on the property in question filed a lawsuit in which they challenged the right of the City of New London to exercise its power of eminent domain for this purpose, and their case moved all the way from Connecticut trial and appellate courts to the U.S. Supreme Court. A majority of justices on the U.S. Supreme Court found that the benefits to the community involved justified the condemnation, and that the City of New London had provided just compensation for the loss of property suffered by the affected homeowners.

In reaction to this decision, many state legislatures viewed the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision as too greatly benefiting large corporations at the expense of families and neighborhood communities. As a result, legislation was introduced in several states and ballot measures were placed on the ballot in other states aimed at amending state constitutions to provide greater protections of private property rights from this type of use (i.e., economic development) of the municipal power of eminent domain. That power is typically employed when there is some pressing need for public ownership of some private land to serve clearly public purposes (for example, creating a roadway for enhanced commercial activity and traffic control).

Some could say the City of New London’s action condemning some private land for the economic benefit of the entire community represents an action in line with the philosophy of sustainability since economic vitality is one of the pillars upon which sustainability rests. Others might argue that such actions threaten sustainability because they displace neighborhoods and promote social inequity in the form of privileged access to large, outside corporate interests. Such varied interpretations are clearly possible, and it is certain that more court cases such as this one will be filed and heard as a consequence of municipal actions taken to promote economic viability coming into conflict with property owners seeking to preserve the current use being made of the land in question.

The Kelo case has caused the strengthening of private property rights in many states because this is a politically popular (and apparently cost-free) action for elected officials to take. However, by strengthening private property rights, states enacting greater protections to homeowners may make it more difficult to promote sustainable development. For example, should a municipality seek to use its power of eminent domain to locate solar collectors to provide cheaper and renewal energy to its utility subscribers, should private property owners adversely affected by the location of those collectors be allowed to prevent such a use of eminent domain? Should the pursuit of sustainability goals be one of the “reasonable grounds” justifying the use of eminent domain in the states where laws more protective of homeowners’ rights were enacted in the wake of the Kelo case? One thing is for certain, state court and the judges sitting on trial court and appellate court benches in our states will be hearing just such cases in the years ahead. The question of how those courts are staffed and who presides in those courts is a question well worth our careful attention.

State and local courts have greatly impacted sustainability in the past, and they will most certainly do so in the future. Generally speaking, the higher the level of the court, the larger the swath of impact its actions have on sustainability. If a state’s Court of Last Resort makes a precedential ruling, then the state’s lower courts must follow the dictates of that ruling. This is not to say trial courts are unimportant, as they are most often the first to hear a case that could lead to a change in the law, good or bad, around the rest of the state. Illustrative of the clear importance of courts in the area of sustainability promotion in state and local government, the case of the widowed grandmother in Orem, Utah stands out. This elderly woman was arrested and taken away in handcuffs for refusing to give a policeman her name so he could issue her a ticket for failing to water her lawn on a regular basis, a violation of an Orem zoning ordinance. If the case goes to trial, it would be heard in the Orem Municipal Court. The reason the grandmother provided for not watering her lawn was that of inability to afford the expense associated with maintaining a green lawn. However, the national attention generated from the case has led to question as to why someone should have to defend themselves in court for a practice that is both uneconomical and wasteful of a precious natural resource – particularly since Utah is the second driest state in the nation.

More recently some state supreme courts have increasingly been engaging in a variety of sustainability initiatives to reduce their environmental impact and promote sustainability within their jurisdictions. For example, the California judiciary has been proactive in implementing sustainability practices across its own court facilities. Some examples of these efforts include the following:

- Energy Efficiency: The state has retrofitted lighting in 38 courthouses with LED technology, which is significantly more energy-efficient than traditional lighting. This switch not only saves approximately $1.5 million annually in electricity costs, but also reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 2,306 tons each year.

- Automation Systems: Automation technologies are being installed to better manage and monitor energy usage at individual courthouses. This technology allows for more precise control over energy consumption, helping to identify and minimize wastage.

- Clean Energy Goals: The California court system aims to move to 100% clean energy, aligning its operations with broader state and national environmental objectives. This shift includes integrating renewable energy sources into their power supply, reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

- Infrastructure Investment: The sustainability plan calls for substantial investment in courthouse infrastructure to support these initiatives. This includes both upgrades to existing facilities and the construction of new ones designed with sustainability in mind.

- Educational Outreach: The courts are also focusing on educating judicial staff and the public about the importance of sustainability. This is intended to foster a culture of environmental responsibility within the state judiciary and among courthouse users and visitors.

Achieving these goals requires significant financial investment. The state's judicial branch alone needs an estimated $5 billion for deferred maintenance, highlighting the scale of the challenge. The courts continue to explore additional ways to enhance sustainability. This includes potential updates to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems, and other large-scale infrastructure projects. These efforts reflect a broader trend in the judicial system toward embracing sustainability not only as a means to reduce environmental impact, but also to actively promote operational efficiency and cost savings over the long term (Corren, 2022).

Current Trends in State Supreme Courts

Current trends in U.S. state supreme courts include a focus on modernization, diversity, and shifts in judicial reasoning:

Technological Modernization: The push for technological modernization in state courts is a significant trend that aims to enhance judicial efficiency and broaden access to justice. This trend includes the expanded use of virtual court proceedings, which have proven particularly beneficial in increasing accessibility for many litigants, especially those in remote areas or with mobility limitations. The transition to virtual environments allows courts to conduct hearings and other legal processes more flexibly and inclusively, ensuring that more people can engage with the justice system without the barriers of physical travel and presence. However, this shift towards digital proceedings is not without noteworthy challenges. Key issues include the variability in internet access and the wide range of digital literacy present among users. These factors can significantly affect the ability of some litigants to effectively participate in virtual hearings. Despite the progress in implementing virtual court technologies, the disparity in digital access remains a substantial hurdle that courts need to address to ensure equitable access to justice for all citizens. The Thomson Reuters Institute highlights these ongoing efforts and challenges, noting that while technological upgrades have improved court accessibility and efficiency, the need for improvements in digital infrastructure and education is critical to fully realizing the potential benefits of these technologies (Thomas Reuters Institute, 2023).

Diversity: The movement toward greater diversity in state supreme courts marks a significant shift in the judicial landscape, reflecting broader societal advancements toward inclusivity. Recent notable appointments include the first Black women justices on the Illinois Supreme Court, which are significant milestones that underscore the progress in judicial diversity. Similarly, the appointment of the first openly lesbian justice on the California Supreme Court highlights the increasing high levels acceptance and representation of the LGBTQ+ community with the judiciary. These changes are not just symbolic; they bring diverse perspectives and experiences to the bench, which can influence judicial reasoning and decision-making. This diversity enriches the court's understanding of the issues that come before it, reflecting a broader array of viewpoints and potentially leading to more nuanced and equitable judicial outcomes. The Brennan Center for Justice notes these developments as part of a necessary progression towards a judiciary that mirrors the population it serves, enhancing the legitimacy and credibility of the judicial system. Such shifts in judicial appointments also stimulate discussions about equity, representation, and the role of identity in justice, which are crucial for the ongoing evolution of the legal landscape. As these trends continue, they may encourage further reforms and initiatives aimed at promoting diversity within other areas of governance and public service (Powers and Bannon, 2023).

Judicial Reasoning and Decisions: State supreme courts play a critical role in interpreting both constitutional and administrative law, significantly influencing legal norms and public policy across the U.S. These courts frequently tackle complex legal issues that can reshape state and national legal frameworks. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous state supreme courts dealt with cases related to eviction moratoriums. These decisions often revolved around whether such moratoriums constituted a taking of private property without compensation, challenging the balance between public health concerns and property rights. Moreover, state supreme courts address cases involving the enforcement powers of state agencies, scrutinizing the extent of these powers and their application. Decisions in such cases can redefine the boundaries of state power, affecting how agencies implement regulations impacting everything from environmental policy to economic management. These decisions are pivotal, not just for the immediate parties involved but also for setting legal precedents that guide future cases. By interpreting state constitutions and laws, these courts influence the broader legal landscape, contributing to the evolving dialogue about rights, governance, and justice in the United States. Such cases and their outcomes provide critical insights into the dynamics of law and authority, reflecting broader societal values and the changing priorities of the judiciary (State Court Report (2023).

Aging Judiciary and Performance: The issue of mandatory retirement for judges addresses a significant aspect of judicial administration. Research indicates that implementing mandatory retirement can improve court performance. Such policies potentially rejuvenate the judiciary by infusing it with younger judges who may bring new perspectives and efficiencies to their roles. This dynamic might accelerate court processes and enhance the quality of judicial decision-making, reflecting a judiciary that adapts actively to societal and demographic shifts. The push for mandatory retirement is part of a broader conversation about how courts manage changes in the composition of the judiciary. It considers how an aging workforce might affect the judiciary's ability to function efficiently and uphold high legal standards. This discussion aligns with the need for a balance between experience and innovation within the judiciary to maintain robust and responsive legal systems (Ash and Macleod, 2023).

Political Polarization and State Supreme Courts

Another trend most visible in the increasingly polarized political landscape wherein the U.S. Supreme Court is now seen as a partisan center of political power after overturning the 50-year precedent Roe v. Wade decision. State supreme courts are increasingly becoming politicized and handling controversial issues such as reproductive rights and LGBTQ protections, a persisting trend toward partisan politicization influenced by several key factors:

Federal Decentralization and State Court Roles: The decision to overturn Roe v. Wade removed the federal constitutional protection of abortion rights, fundamentally changing the legal landscape for reproductive rights. No longer uniformly regulated by federal mandate, the authority to govern abortion laws reverted to individual states. This decentralization has led to a patchwork of regulation pertaining to abortions and medical practice, with states enacting a variety of restrictions or protections based on local political and cultural climates. In the wake of this federal shift, state supreme courts and inferior state courts have assumed a pivotal role in determining the constitutionality and enforcement of state-specific abortion laws. These courts now directly influence the accessibility of abortion services and medical care within their jurisdictions by interpreting state constitutions in the context of abortion rights.

The Supreme Court of Mississippi swiftly became a focal point in the post-Roe era. It was among the first to uphold restrictive abortion laws following the reversal. Mississippi's law, which bans nearly all abortions with very few exceptions, faced legal challenges that rapidly escalated to the state's highest court (Taft, 2022). The court's decision to uphold the strict ban on abortions showcased the enhanced and critical role state supreme courts now play in interpreting and applying laws that have profound impacts on public health and individual rights. This decentralization not only affects the residents of states with restrictive laws, but also sets a precedent that influences other states' legal landscapes. As each state supreme court issues rulings on abortion, they contribute to a collective reshaping of how reproductive rights are understood and implemented across the country in the wake of the abandonment of the Roe v. Wade precedent (Levinson-King, 2023). These decisions can also prompt legislative reactions, both at the state and federal levels, further emphasizing the significant judicial influence state supreme courts hold in the current American legal framework.

Legislative Actions at the State Level: State legislatures, reflecting the political and social divides within their jurisdictions, are passing increasingly bold legislation that challenges existing federal norms and precedents. These laws cover a wide array of issues, from abortion to LGBTQ rights to gun control to library book banning, and they often provoke immediate legal challenges. This is particularly true in states like Texas, where recent legislative sessions have seen the introduction of laws that directly impact the lives of transgender individuals. In Texas, legislation was introduced that specifically targeted transgender youth. These laws included measures to ban transgender athletes from participating in school sports that align with their gender identity and restrictions on access to gender-affirming healthcare for minors. These legislative actions sparked significant controversy and were quickly challenged in courts. The cases concerning these laws were escalated to the Texas Supreme Court, whose decisions on these matters carry wide-reaching implications. The court's rulings will not only affect the lives of transgender youth in Texas, but also set legal precedents that could influence the crafting and enforcement of similar laws in other states. For example, a decision by the Texas Supreme Court to uphold these laws could embolden other states with similar political alignments to enact comparable legislation, thereby affecting national policy trends on transgender rights (Melhado, 2023). The outcomes of such legal battles are critical because they test the extent to which state laws can diverge from federal precedents and protections under the Constitution. They also explore the balance of power between state autonomy and individual rights. Decisions made in state supreme courts, therefore, do not just resolve local legal disputes but also contribute to the shaping of national legal landscapes, potentially influencing legislation and judicial decisions far beyond their state of origin.