Chapter 6: State Constitutions

Introduction

On November 2nd of 2004 voters in Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon and Utah voted to change their respective state constitutions to make same-sex marriage illegal (which has since been nationally legal with the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2015 decision in Obergefell, et al. v. Hodges, et al.). Over the last decade voters in some of these same states, and others, have decided to attach additional amendments to their state constitutions to legalize marijuana, to allow physician-assisted suicide, to ban the use of dogs in the hunting of bear and mountain lions, to protect the privilege of gathering some types of edible seaweed, to increase the share of state budgets allocated to education, to ban abortion, to increase cigarette taxes, to increase the minimum wage, to either limit or increase the scope of taxes and tax rates, among other things.

State constitutions may seem like an unusual place to pursue one’s favored public policies – instead of the normal legislative process – but this way of starting out our discussion of state constitutions indicates how important these foundational documents are in the daily lives of American citizens. Given citizen familiarity with the U.S. Constitution and the institutions of the national government generally is typically quite low in some areas (in this regard, see Table 6.1), popular familiarity with and knowledge of state constitutions is most likely even lower in most areas of the country (Tarr, 1998). Even among the academic community, there has been relatively limited research regarding state constitutions in contrast to the virtual mountain of literature devoted to the decisions and operations of the U.S. Supreme Court regarding the interpretation of the U.S. Constitution and to the selection of members of the federal bench whose terms of office are “for life” (the sole exception from fixed terms of office in the American governmental system).

Table 6.1 U.S. Civic Knowledge 2018

| - | Percent correct answer |

|---|---|

| a. Free speech is guaranteed by First Amendment. | 86% |

| b. Republican Party has majority in Senate. | 83% |

| c. Republican Party has majority in House of Representatives | 82% |

| d. Electoral College formally elects the president | 76% |

| e. 22nd Amendment determines max number of presidential terms | 56% |

| f. Vice President casts tie-breaking votes in Senate | 54% |

| g. 60 votes needed to end a filibuster in Senate | 41% |

Source: Pew Research Center, Political Engagement, Knowledge and the Midterms, April 26, 2018. URL: http://www.people-press.org

While state constitutions don’t receive much attention from academic researchers and are accorded only scant public attention, their importance does indeed merit our serious attention. We decided to include an entire chapter on state constitutions given their direct connection to the question of the active pursuit of sustainability in state and local government. The mere mention of the topic usually tends to arouse some dread of boredom born of painful attention to legalistic hair-splitting among students of state and local government. In fact, in reality state constitutions represent a topic of great importance, interesting historical developments, and clear contemporary relevance. As G. Alan Tarr has reminded us (1998):

…the disdain for state constitutions is unfortunate; for one cannot make sense of American state government or state politics without understanding state constitutions. After all, it is the state constitution — and not the federal constitution — that creates the state government, largely determines the scope of its powers, and distributes those powers among the branches of the state government and between state and locality.

State constitutions are also important to examine because they often mirror important political, economic and social changes occurring over time. As states have moved from reflecting rural economies characterized principally by natural resource extraction in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (mining, timber, fisheries and agriculture), to governing urbanizing industrial economies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (manufacturing), to providing guidance to postindustrial and knowledge-based economies in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, citizens and their political representatives have made many revisions to their respective state constitutions – and even replaced them in their entirety when deemed necessary on rare occasion. Such adaptation to change is a key element in the promotion of sustainability.

While there is somewhat of a debate taking place regarding just how adaptive state constitutions have been to changing times and situations, there is little disagreement that constitutions are important documents that set the context and specify the procedures for political processes wherein governors, legislatures, state and local courts, interest groups, local governments, citizens, and others seek to influence the course of public policy.

Because of the clear importance of state constitutions to American state and local politics and to prospects for sustainable governance, this chapter will:

- review the purpose of constitutionalism and constitutions in the states

- analyze key differences and similarities between state constitutions

- discuss the various processes available for changing constitutions in the states

- and examine the role of state constitutions as both barriers to and promoters of sustainability

Purpose of State Constitutions

According to Francis Wormuth’s classic work entitled The Origins of Modern Constitutionalism (1949), “A constitution is often defined as the whole body of rules, written and unwritten, legal and extralegal, which describe a government and its operation.” The use of constitutions in states mirrors the development of what we call constitutional democracy at our national level of government. At its most basic level the concept reflects the belief that government can and should be legally limited in its powers, and that its rightful exercise of authority depends on observing these limitations. Government in a democratic country must be accountable to its citizens and operate within the limits placed on how and when governmental power is to be exercised with respect to the rights and privileges of citizens. While most constitutions in the world, including that of the United States, are codified as single written documents, the notion of constitutionalism can also include multiple written documents and even some unwritten rules and procedures. In the case of Great Britain, for example, there are various written components of the constitution such as the Magna Carta (1215 AD) and numerous statutes enacted by Parliament, but there are also some unwritten components including principles derived from Common Law and Royal Prerogative.

We can trace the development of constitutionalism back to 500-600 BC in ancient Greece where some city states had partially written or customary constitutions that were organized, according to the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC), into either good or bad forms of the rule of one (kingship versus tyranny), the rule of few (aristocracy versus oligarchy), and the rule of many (polity versus mob rule). Constitutionalism in the United States was influenced by various sources, including developments in Common Law in Great Britain and the well-known writings of enlightenment thinkers such as Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778 AD) and John Locke (1632-1704 AD) (Stoner, 1992).

While the U.S. Constitution is often considered the oldest written constitutional document still in use in the world, several American state constitutions are even older than the U.S. Constitution – stemming from the original charters of the thirteen colonies (see Table 6.1). The constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is quite likely the oldest written constitutional document still in use; it dates back to 1780. The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut was considered the first written quasi-constitutional document of its kind in the world, dating from 1638 (Maddex, 2006). Eleven other American states’ first constitutions precede the U.S. Constitution of 1787 by at least a decade, illustrating that the concept of constitutionalism was well instilled at the state level well before the creation of our current national government (Council State Governments, 2006). In point of fact, many of the framers of the U.S. Constitution meeting in Philadelphia in the late 1780s were quite heavily influenced by their deep knowledge of and experience with their respective colonial constitutional documents and established governmental practices.

In general, it can be said that state constitutions establish the overall framework of state government, specifying the forms of local governments to be permitted – including all cities, counties, townships and special purpose districts created within its territory. The state constitutions provide for all forms of state and local government finances, establish the state and local tax systems in force, and designate the range of civil liberties to be protected under state law. In a sense, state constitutions represent a form of societal contract between those in elected or appointed office and the rest of society. All disputes concerning the meaning of that contract are settled in state supreme courts. Specifically, the main purposes of state constitutions are (within the limitations placed on states by the U.S. Constitution):

- to define the general purposes and ideals of the several states, including the determination of the common good of citizens

- to establish republican and accountable forms of government, with legal limits on the powers of government entities and their agencies

- to provide a framework for governmental structures, including the scope of authority, mechanisms for exercising authority, and procedures for the passage and modification of state laws, local ordinances, and administrative rules and regulations. This framework includes the executive, legislative and judicial branches of state and local government

- to provide for an independent judiciary that allows citizens to seek court-ordered remedies for illegal actions of government as well as a process to challenge laws they believe to be unconstitutional

- to provide legal definitions of key concepts (e.g., citizenship, property rights, parental rights, etc.) and prescribe a process for establishing basic political rights such as standing for public office and voting

- to establish and define the powers of local governments, including counties, cities, townships and special purpose governments

- to establish the requirements for holding elective and appointed office, as well as setting the terms of office for elected officials

- to provide for a process of removal of incompetent and/or corrupt elected or appointed officials, which can include recall and impeachment

- to define responsibilities for major government departments and agencies, and the principal duties of the individuals heading up those state and local governmental entities

- to establish a system of taxation and budgetary processes

- to provide for the public safety of the citizenry, including regulatory authority for civil and criminal actions to be exercised to promote public health and safety and to operate effective civil and criminal justice systems

- to provide for a process of replacing or revising the state constitution (depending on the state, these processes can include initiatives, referenda, constitutional conventions and legislative action)

- to establish the rights of citizens, including both “negative” and “positive” rights and freedoms. Negative freedoms are often called “civil liberties,” which include freedom of speech and assembly among other rights. Civil liberties are individual or group protections from a potential oppressive government. Positive rights, on the other hand, are things government can do for citizens, including the provision of education, economic assistance in times of need, timely assistance in times of natural disasters, and the preservation of cultural assets with public libraries and museums

While these are the major purposes of state constitutions generally speaking, it should be noted here that considerable diversity exists among the states on many of these principles, and this diversity will be discussed in the next section of this chapter. Before we begin this particular discussion we would be wise to heed Robert Maddex’s cautionary advice concerning the vast complexity and dynamic nature of constitutionalism in a federal system (2006):

Unlike national constitutions, state constitutions do not simply stand alone at the apex of a system of laws but are part of an interactive organization of federal and state governments. Federalism, which is an attempt to solve the problems that arise from this interaction between national and state laws, has continued to evolve since the nation was founded.

Content of State Constitutions: Diversity and Similarities

In broad terms, state constitutions and governmental structures greatly resemble the U.S. Constitution and the national governmental structure because those pre-existing features of government were used as a guide by the framers of the U.S. Constitution. State constitutions differ substantially from state to state, but they are similar in that they are not permitted to contradict the supremacy clause of the U.S. Constitution. Where the U.S. Constitution prescribes a legal standard of democratic governmental form or practice, all state constitutions must be consistent with that standard. In the case of civil liberties, for example, the several states may exceed but may not set lower standards for the protection of those rights of citizens than those established by the U.S. Supreme in its interpretation of the Bill of Rights of the U.S. Constitution.

The limits as to what states can and cannot do with respect to the supremacy civil liberties clause are rather clear (see figure 6.1). The U.S. Constitution sets specific limits on state powers in Article I, Section 10; that section restricts states from printing their own money, entering into international treaties, imposing duties on international trade, and engaging in various other official activities reserved for federal government actions. Article IV, Sections 1 through 4 specify other provisions pertaining to the states, including extradition of individuals accused of a crime in another state, the requirement for a republican form of government, and the process by which new states can be admitted to the union. Importantly, as noted in the chapter on intergovernmental relations in our federal system of government, the Tenth Amendment specifies that any powers not specifically granted to the federal government in the U.S. Constitution are reserved to the responsibility of the states and the people (this is known as the reserved powers clause).

Article I

- No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

- No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it’s inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the United States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Control of the Congress.

- No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

Article IV

- Full Faith and Credit shall be given in each State to the public Acts, Records, and judicial Proceedings of every other State. And the Congress may by general Laws prescribe the Manner in which such Acts, Records and Proceedings shall be proved, and the Effect thereof.

Section 2 – State citizens, Extradition

- The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.

- A Person charged in any State with Treason, Felony, or other Crime, who shall flee from Justice, and be found in another State, shall on demand of the executive Authority of the State from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the State having Jurisdiction of the Crime.

- (No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, But shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.) (This clause in parentheses is superseded by the 13th Amendment.)

Section 3 – New States

- New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

- The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

Section 4 – Republican government

- The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.

Tenth Amendment

- The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Figure 6.1 Key U.S. Constitution Provisions Concerning States

According to research conducted by Christopher Hammons, there have been 145 constitutions in the 50 U.S. states since 1776, with the average constitution remaining in effect for approximately 70 years. On average, American state constitutions are “…almost four times longer than the 7,400-word U.S. Constitution. Most state constitutions contain around 26,000 words” (Hammons, 1999). Currently, the shortest state constitution is found in New Hampshire, a document featuring only 9,200 words; in stark contrast, the longest state constitution contains 340,136 words and it is found in Alabama (see Table 6.2). All of the state constitutions are longer than the U.S. Constitution. The reason that state constitutions are longer than the U.S. Constitution is “…because they encompass such a wide range of institutions and powers” due to the dictate of the Tenth Amendment where “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution…are reserved to the States, respectively” (Hammons, 1999). In addition, Hammons argues that the number of “statutory-type provisions” found in state constitutions – that is, specific mandates for specific public policies – are quite numerous, with the average state having 824 separate provision, of which “…324 are devoted to particularistic or statutory issues” such as the provision of hail insurance in South Dakota, citizen access to physician-assisted suicide in Oregon, the width of ski runs in New York, and the active promotion of the catfish farming industry in Alabama (Hammons, 1999).

Table 6.2 State Constitution Characteristics

| State: | Capital: | Number of Constitutions: | Year Present Constitution Implemented: | Length in Words: | Amendment Adopted: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Montgomery | 6 | 1901 | 240,136 | 766 |

| Alaska | Juneau | 1 | 1959 | 15,988 | 29 |

| Arizona | Phoenix | 1 | 1912 | 28,876 | 136 |

| Arkansas | Little Rock | 5 | 1874 | 59,500 | 91 |

| California | Sacramento | 2 | 1879 | 54,645 | 513 |

| Colorado | Denver | 1 | 1876 | 74,522 | 145 |

| Connecticut | Hartford | 4 | 1965 | 17,256 | 29 |

| Delaware | Dover | 4 | 1897 | 19,000 | 138 |

| Florida | Tallahassee | 6 | 1969 | 51,456 | 107 |

| Georgia | Atlanta | 10 | 1983 | 39,526 | 63 |

| Hawaii | Honolulu | 1 | 1959 | 20,774 | 104 |

| Idaho | Boise | 1 | 1890 | 24,232 | 117 |

| Illinois | Springfield | 4 | 1971 | 16,510 | 11 |

| Indiana | Indianapolis | 2 | 1851 | 10,379 | 46 |

| Iowa | Des Moines | 2 | 1857 | 12,616 | 52 |

| Kansas | Topeka | 1 | 1861 | 54,112 | 93 |

| Kentucky | Frankfort | 4 | 1891 | 16,276 | 41 |

| Louisiana | Baton Rouge | 11 | 1975 | 46,600 | 129 |

| Maine | Augusta | 1 | 1820 | 16,276 | 170 |

| Maryland | Annapolis | 4 | 1867 | 46,600 | 218 |

| Massachusetts | Boston | 1 | 1780 | 36,700 | 120 |

| Michigan | Lansing | 4 | 1964 | 34,659 | 25 |

| Minnesota | Saint Paul | 1 | 1858 | 11,547 | 118 |

| Mississippi | Jackson | 4 | 1890 | 24,323 | 123 |

| Missouri | Jefferson City | 4 | 1945 | 42,600 | 105 |

| Montana | Helena | 2 | 1973 | 13,145 | 30 |

| Nebraska | Lincoln | 2 | 1875 | 20,048 | 222 |

| Nevada | Carson City | 1 | 1864 | 31,377 | 132 |

| New Hampshire | Concord | 2 | 1784 | 9,200 | 143 |

| New Jersey | Trenton | 3 | 1948 | 22,956 | 38 |

| New Mexico | Santa Fe | 1 | 1912 | 27,200 | 151 |

| New York | Albany | 4 | 1895 | 51,700 | 216 |

| North Carolina | Raleigh | 3 | 1971 | 16,532 | 34 |

| Ohio | Columbus | 2 | 1851 | 48,521 | 162 |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma City | 1 | 1907 | 74,075 | 171 |

| Oregon | Salem | 1 | 1859 | 54,083 | 238 |

| Pennsylvania | Harrisburg | 5 | 1968 | 27,711 | 30 |

| Rhode Island | Providence | 3 | 1986 | 10,908 | 8 |

| South Carolina | Columbia | 7 | 1896 | 22,300 | 485 |

| South Dakota | Pierre | 1 | 1889 | 27,675 | 212 |

| Tennessee | Nashville | 3 | 1870 | 13,300 | 36 |

| Texas | Austin | 5 | 1876 | 90,000 | 439 |

| Utah | Salt Lake City | 1 | 1896 | 11,000 | 106 |

| Vermont | Montpelier | 3 | 1793 | 10,286 | 53 |

| Virginia | Richmond | 6 | 1971 | 21,319 | 40 |

| Washington | Olympia | 1 | 1889 | 33,564 | 96 |

| West Virginia | Charleston | 2 | 1872 | 26,000 | 71 |

| Wisconsin | Madison | 1 | 1848 | 14,392 | 134 |

| Wyoming | Cheyenne | 1 | 1890 | 31,800 | 94 |

Source: The Book of the States, Lexington, Kentucky: Council of State Governments.

Many observers argue that longer constitutions featuring many specific mandates make state constitutions overly cumbersome and time-bound, and consequently less likely to last over time. They believe that more streamlined constitutions focusing mostly on institutional issues (e.g., governmental structures and functions) with fewer specific mandates make them more durable and adaptable over time (Blaustein, 1990; Friedman, 1988). However, contrary to this conventional argument Hammons’ research into state constitutions found “…that longer and more detailed design of state constitutions actually enhances rather than reduces their longevity” (1999). While Hammons does not know for sure why more detailed and longer constitutions can be shown to be more durable, he conjectures that this may occur because such documents provide better mechanisms for conflict resolution by more carefully identifying the rules of the game to be followed by parties in dispute. He also notes that the longer “particularistic” constitutions may have proven to be more durable because they provide competing groups a common interest to protect the important foundational document wherein “…their programs are institutionalized” (Hammons, 1999).

While the length of state constitutions varies widely, there are many common themes found among their provisions, including the establishment of government institutions, the specification of powers of these institutions, the procedures to be followed by public institutions in carrying out their work, and the principles of governance to be observed. Regarding the establishment of governmental institutions, the U.S. Constitution allows a wide variety of institutions as long as they represent a republican form of government. Typically, when we talk about institutions in this context of republican government there are two primary issues to consider. First, there is separation of powers versus integration of powers, which concerns how many branches of government will be established. Branches can be divided up by executive, legislative and judicial powers, or integrated into one body, such as done in a European-style parliament. The second issue involves centralization versus decentralization, which concerns how many layers of government will be used and how much power and responsibility each layer will have. Government responsibilities can be centralized at one level of government, or they may be broadly dispersed and decentralized among multiple layers. In some cases, powers can be shared to a degree.

For both the separation of powers and centralization vs. decentralization issues state constitutions closely resemble the U.S. Constitution in that power is separated into three branches – executive, legislative and judicial – and government is decentralized; the governmental powers within the states are typically distributed across five possible layers, including counties, cities, townships, school districts and special purpose districts. For the branches of government found in states, the executive branch is headed by a governor instead of a president, each state has two legislative chambers (with the exception of Nebraska which has just a single chamber), and each state has a court of last resort (typically referred to as the state’s Supreme Court). As for layers of government, each state has its own procedures for the establishment of local governments, and states differ in how much power and what range of responsibilities those local governments can exercise. Forty-eight states have operational county governments (called “boroughs” and “parishes” in Alaska and Louisiana, respectively). While the states of Connecticut and Rhode Island provide for counties as geographic subdivisions of the state, these regional subdivisions do not have functioning governments in those two states.

All fifty states allow for general purpose municipal forms of government, and all states have school and special purpose (e.g., sewer, mosquito control, rural fire, soil conservation) districts. Twenty states also allow for township governments, which historically have been rural subdivisions of counties, but not always; in fact, today many metropolitan area suburbs with growing populations have spread into previously rural locations.

Other governmental institutions typically seen in state constitutions include the establishment of state offices and officials, including executive agencies and departments such as education, transportation, agriculture, fish and game, natural resources and the environment, attorney general, secretary of state, treasury, revenue, welfare (social services), health, civil service, various advisory boards, commissions, and governing boards for public colleges and universities. Typically, state constitutions also establish institutions such as state prisons, state mental health hospitals, state libraries, and state parks, and states provide for local school districts and other forms of local government-oriented entities to deal with such infrastructure matters as public utilities, irrigation, county roads and bridges, park and recreation facilities, local libraries and health clinics and hospitals.

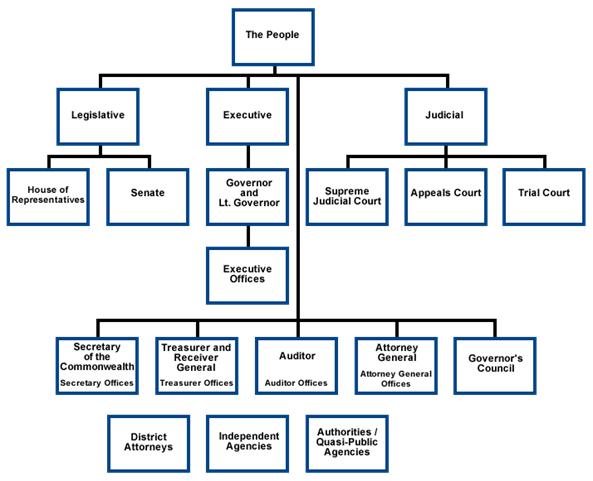

The powers residing in each institution and the state in general are also included in state constitutions, such as the legislative power for both upper and lower chambers; executive powers held by the governor and other executive offices such as secretaries of state and attorneys general; judicial powers held by state supreme courts, state appellate courts, and lower courts; powers of taxation and expenditure; powers of local governments; regulatory powers over various areas, including commerce, transportation, environment, business and corporations, criminal justice; powers to claim land or property for public use – and many more. Most state constitutions provide for a plural executive branch, with separate elections for such offices as secretary of state, state treasurer, attorney general, state auditor, and lieutenant governor. A typical U.S. state governmental structure outlined in a state constitution looks very much like that of one of our oldest state constitutions – namely, that of Massachusetts (see figure 6.2).

State constitutions also outline the process and procedures of government as well. These can include but are not limited to: how laws are made, including executive veto and override processes; qualifications for election and office-holding; terms of office; ballot rules; voter registration and election process rules; size of public institutions; rules for the maintenance of official records; impeachment processes; when and where periodic elections will be held, and who is eligible to vote; processes for initiative, referendum, and referral, and many other procedures not listed here. Forty-four U.S. states allow governors to veto individual items in appropriation bills, and all but 15 U.S. states mandate the adoption into law of “balanced budgets” (that is, expenditures provided for must match anticipated revenue for the period in question) through their state constitutions. Most state constitutions feature term limits for governors (38 states), and 16 states have set term limits for state legislators in their constitutions as well.

Finally, state constitutions also provide the “guiding principles” of governance. These principles often follow the U.S. Constitution and typically include many items found in the Bill of Rights, including freedom of speech, freedom of religion, governmental accountability, the sovereignty of the people, and the purpose of democratic government being the protection of life, liberty, happiness and property. Forty-six states also have provisions similar the U.S. Constitution’s Second Amendment concerning the right to bear arms (California, Iowa, Minnesota and New Jersey are silent on the subject). Only 10 states guarantee the right to privacy in various specific areas, including financial and medical records, but in other states these rights have been established by state Supreme Court decisions. While these fundamental rights are found in the U.S. Constitution and provide citizens with a “minimal floor of government protection for the individual, the enumerated rights in state constitutions can represent another layer” of protection of individual rights (Maddex, 2006).

Changing Constitutions

There are three major methods available to change or amend U.S. state constitutions. The methods include a legislative proposal, a popular initiative, and a constitutional convention. A fourth method, only available in Florida, involves a constitutional commission submitting a proposal directly to the state’s voters for their consideration. Additionally, each state has the potential for a “virtual” constitutional amendment through judicial re-interpretation of constitutional provisions. Of the four methods listed, only the constitutional convention provides elected officials an opportunity to collaborate in a deliberative setting on the entire constitution.

Legislative Proposal: The legislative proposal method is the main avenue used in all the U.S. states to amend their respective constitutions. To demonstrate how heavily this method is used, in the five-year period of 2002-2006 the legislative proposal constituted 68% of all the amendment proposals, with the initiative process comprising the remaining 32%. This legislative process is ordinarily used for making limited changes, but on rare occasions the process has been used in some states to propose rather comprehensive revisions of their constitutions.

What makes the legislative constitutional amendment proposal different than simple legislation is the requirement of a large “super-majority” consensus in both legislative chambers, with the minimum being two-thirds. In addition, fifteen states have an even more arduous hurdle called “Double Passage.” This is an amendment procedure that requires majority consensus by both houses from two separate legislative sessions. Lastly, all states except Delaware require that legislative amendment proposals be submitted to the state’s voters for their ultimate approval by a majority vote. With all these requirements, it seems rather a miracle that so many amendments have made it though the approval gauntlet. Contrary to popular belief, the majority of all state amendments adopted did not garner the general public’s attention or cause controversy at the polls; in fact, about two-thirds of all state amendments deal with rather mundane issues such as state and local governmental structure and debt management, state agency functions, and relatively minor taxation and finance issues (Lutz, 1994).

Constitutional Initiatives: The constitutional initiative, also know as the popular initiative, citizen initiative, minority initiative, and the “Oregon System,” empowers citizens to propose constitutional amendments directly to voters for their ultimate consideration. Available in 18 states, the process is broken down into either direct or indirect initiatives. The direct initiative process allows for a constitutional amendment proposed by the people to be placed directly on the ballot for voter approval or rejection, while the indirect initiative must first be submitted to the state legislature for its consideration before being placed on the popular ballot. Only the states of Mississippi and Massachusetts among the 18 states featuring the initiative process use the indirect initiative process.

Each state has their own requirements for placement on the ballot, but typically an initiative proposal requires a certain percentage of registered voters’ signatures before the state’s voters can place it on the ballot for consideration. In those states where the initiative is in place, it is particularly important that citizens keep informed about state and local government issues; these issues are very likely to come before them as voters on a rather regular basis.

The origins of the initiative process go back to 1902 when the Oregon legislature adopted a constitutional amendment to allow residents of Oregon to propose new laws or change the state constitution through a general election ballot measure (Oregon Blue Book, 2024; Swarthout and Gervais, 1969). This is why the initiative process is known nationally as the Oregon System of direct democracy. Its initial purpose was to provide a means to bypass the political status quo and corruption of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was felt, and rightly so, that many politicians of the day were “in the pockets” of the large private corporate interests of the day — namely, the railroads and timber companies. In response to the positive public opinion developed toward the Oregon System, the initiative process was adopted by 17 additional states and became one of the signature reforms of the Progressive Era. As in the past, those who distrust government still use the initiative today, but there is considerable concern that the process might be somewhat at risk because it tends to empower well-funded special interests that exercise disproportionate access to the ballot box through this process (Cronin, 1989).

Constitutional Convention: A Constitutional convention is the oldest and most traditional method to propose a new state constitution or extensively revise an existing constitution. The process of initiating a convention begins with a formal call from the legislature, an action which all 50 state legislatures and the District of Columbia have the ability to undertake. Fourteen states also require submitting the question of calling a constitutional convention to their voters (Dinan, 2006), thereby requiring the legislature to hold such a conclave. While each state has its own requirements in this regard, most states require majority approval by voters (termed “ratification”) before a new constitution can be adopted in place of an existing foundational legal framework.

Throughout the history of the United States, there have been relatively few constitutional conventions. As of the end of 2009, there have been only 234 constitutional conventions held in the U.S, with Rhode Island holding the last one in 1992 in an effort to address its dire fiscal challenges; the revision proposed was soundly defeated by 62 percent of the state’s voters (May, 1994). The trend of decline in the rate of use of constitutional conventions has been consistent; in the 20th century only 62 conventions were held, compared to 144 in 19th century. There are a number of reasons for this sharp decline, but the biggest possibility is the concern that holding a convention will open up “Pandora’s Box” (i.e., unleash a torrent of issues to which no course of action can be agreed to and ultimate resolution of the issue is not possible). Those on both sides of an issue often fear that a convention is an invitation to provide a forum for either reactionary populism — or the devotion of disproportionate attention to matters of temporary importance, thereby allowing the electorate an opportunity to insert provisions on controversial issues such as abortion, balanced budgets, and the death penalty, or address issues unrelated to the purpose giving rise to the convention (Alvarez and Brehm, 2002; Galie and Bopst, 1996).

For example, in 1997 a coalition of environmental interest groups and teachers’ unions in New York mobilized against a convention call. The environmentalists feared the 1894 “Forever Wild” provision that protects the Catskill and Adirondack Preserves would be altered or removed by pro-development interests. Teachers, on the other hand, were concerned about losing the constitutional guarantee of public employee pensions (Benjamin and Gais, 1996). The trend of declining use of constitutional conventions is unlikely to change due to the political atmosphere of partisan politics, apathy from the general public, and an overall fear of opening Pandora’s Box on the part of many organized interests. Framing a new constitution requires both consensus from political parties and widespread and durable support from the general public. These conditions are seldom met in most states.

Constitutional Commission: The constitutional commission is an entity that all states have the ability to use, but few in the general public have ever heard of the process. This is likely due to the fact that, with the exception of Florida, commissions have no direct contact with the public or voters. Each state commission’s role and membership varies from that of other states, but traditionally they represent a group of experts who are appointed, usually by the legislature and/or governor, to review the constitution and submit proposed amendments to the legislature or prepare for a constitutional convention. If members are deemed to be impartial, the commission can be successful; legislatures typically consider commission recommendations carefully if the commission is deemed to be unbiased, nonpartisan and expert in constitutional law.

With the decline of constitutional conventions, some states are turning to constitutional commissions to make their constitutions more workable in a time of need for periodic piecemeal amendments. The state of Utah, for example, in 1969 adopted a law to establish the Constitutional Revision Study Commission to study the state’s constitution and make periodic revision or amendment recommendations to the governor and state legislature (Utah State Law Library, n.d.). The commission was made permanent in 1997, and given the official title of Constitutional Revision Commission. This entity represents the nation’s only permanent constitutional commission; all the other states with such commissions feature bodies which are the temporary creations of specific, time-bound legislation.

The state of Florida’s Taxation and Budget Reform Commission is the only state-level commission that maintains direct contact with the state’s voters. Florida’s commission has the authority to submit recommended budgetary and tax-related constitutional changes directly to the voters, without prior approval from the legislature. In fact, in 1992 Florida made history when its voters approved amendments submitted by the commission without legislative action.

Role of the Courts: The state courts have a major role in amending state constitutions via their exercise of the power of judicial review. Unlike the U.S. Supreme Court, which under most circumstances won’t address “political questions” (legally classified as “nonjusticiable” issues), state appellate courts often rule on a wide range of both procedural and political issues. In the past, state courts of last resort have ruled on issues such as whether a particular state can call a constitutional convention, the validity of procedural mechanisms used in carrying out eminent domain powers, and whether some amendments developed by legislative and popular initiative are consistent with constitutional principles. Because state appellate court judges are elected in most states, unlike their lifetime appointment judicial counterparts in the federal courts, state court judges generally have a stronger sense of connection to “the people” than do members of the federal judiciary. As such, state courts are much more likely than federal courts to issue rulings and hear cases that federal courts would not consider.

Opponents of particular constitutional amendments enacted through the initiative process frequently have used the state courts to question the legality of such amendments in order to prevent them from being placed into effect. For example, opponents of Oregon’s ballot initiative 36, which amended the Oregon constitution to say “that only a marriage between one man and one woman shall be valid or legally recognized as a marriage” (Oregon Blue Book, 2007) unsuccessfully used the state courts to challenge the initiative, arguing in their brief that this statement represented such a radical change to the constitution that only the legislature or constitutional convention should have the ability to make such changes in the foundational framework of Oregon’s legal system. State supreme courts can deny a constitutional initiative a place on the ballot on the grounds that the content of the initiative was inconsistent with provisions of the U.S. Constitution. Such was the case in Colorado when a state district court held invalid an initiative intended to restrict the legal status of gays, lesbians and bisexuals under Colorado law. That ruling was subsequently allowed to stand as precedent in the state.

The role of the state courts known as the exercise of Judicial Federalism is a fairly recent phenomenon emerging in the 1970s when Warren Burger succeeded William Brennan as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. As the U.S. Supreme Court lost its liberal majority with the appointment of Burger, and began to take a far less progressive stance on civil liberties and social equity cases, the high courts in the states began interpreting their own constitutions to establish citizen rights in their states beyond those present in the U.S. Constitution (Tarr, 1998). Judicial Federalism is said to occur when state courts address their own state’s constitutional claims first in a case, and only consider federal constitutional claims when cases cannot be resolved on state grounds. This phenomenon ties directly into the enhancement of state civil liberties in many states during the 1970s, as state supreme courts worked to secure civil rights and liberties unavailable to their citizens under the U.S. Constitution as that document was being read by the members of the conservative Burger Court (Tarr, 1998). This activism on the part of state supreme courts adds an important dimension to the adaptive capacity of state government in the area of the promotion of an essential element of sustainability – namely, the promotion of social equity. Having established this capacity for court-initiated adaptation to change, this same capacity for adaptive action could be demonstrated in the area of citizen positive rights relating to governmental actions taken to address global climate change or energy shortages or access to information technology, for example; the social equity dimensions of those policies would have to pass muster with state courts even if the Congress remained silent on these matters.

Constitutional Amendment Trends

Over the past two centuries U.S. states have amended and revised their constitutions for a wide variety of reasons, whether to change their fiscal structure, to modernize their practices with the times, or to implement requirements for consistency in law coming from the federal courts. Often though, these changes featured in amendments to state constitutions have been in reaction to a larger issue or policy matter arising in the nation’s political discourse. We can anticipate such revisions to arise in connection to the promotion of sustainability in the years ahead as American state and local governments endeavor to adapt to the challenges of global climate change, ongoing environmental degradation, and the growing competition for and increased scarcity of some critical natural resources such as rare earth minerals.

The most prominent trend in state constitutional revision during the 19th century was the creation or complete revision of state constitutions through the constitutional convention process. In all, 41 different states completely revised their respective constitutions a total of 94 times. Thirty of those constitutional conventions were held to create entirely new constitutions for former territories that obtained statehood, but the majority of the 94 constitutional conventions were tied to the national turmoil that came before, during and after the American Civil War (1861–1865). Most of the states which left the union adopted a new constitution just prior or during the Civil War. During the Reconstruction Era ten of the southern states used the convention process to adopt a new constitution, and other unionist states changed their state constitutions to address the change in status of African Americans (Tarr, 1998). As a whole, the American states’ respective constitutional agendas tended to reflect the political movements of the time, including Jacksonian Democracy prior to the Civil War and the Progressive Era toward the end of the 19th century (see Boorstin, 1953). During the later period, the aims of the Progressive Movement reformers were reflected in the drive on the part of state legislatures and state courts alike to regulate more effectively the growing power and influence of private corporations, and to expand the suffrage beyond that of propertied white males (Seidelman and Harphan, 1985).

If the 19th century’s theme with regard to constitutionalism featured the accomplishment of wholesale constitutional reform through the holding of many constitution conventions, then it can be said that the 20th century was a time of piecemeal reform attained through the adoption of many amendments. Two potential reasons for this change are the introduction of the initiative process (the Oregon system) and the shift in the general public’s perception of patriotism and sense of place. Through much of the 19th century, political activity and patriotism was centered within one’s home state, but the Civil War, in the end, preserved the Union and marked the period of ascendance of national over state identity (Benjamin and Gais, 1998). This Civil War-related outcome, combined with dramatic population growth, massive immigration from European countries and cross-continental settlement occurring during the early 20th century made states’ constitutions less of a revered and out-of-reach grand symbol and more of a “working document” to be amended as necessary in order to govern effectively in rapidly changing times. As noted earlier in this chapter, the wide adoption of the constitutional initiative was part of a broad process of placing democracy more fully within the reach of the general voting public. This point is a key one with respect to the need for such adaptive modifications of state constitutions to promote the goals of sustainability in the 21st century.

The 20th century also represents a time when American states diverged widely on their approach to civil rights, with some states amending their constitutions to expand rights while others moved in the opposite direction to limit existing rights. Many southern states took the opportunity to amend their constitutions to re-establish dimensions of white supremacy in the aftermath of Reconstruction (Tarr, 1998), such as North Carolina’s amendments instituting a literary test and a poll tax. In stark contrast, states in the West, including Wyoming and Colorado, amended their state constitutions to establish women’s suffrage well before the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution afforded the right of women to vote as a feature of American citizenship. In the later part of the century there were numerous amendments on civil rights, and some expanding of rights that coincided with Judicial Federalism. The particular area of the rights accorded to the criminally accused, however, became a frequent a target of substantial rights restriction; of the 40 rights-restrictive amendments put into place between 1970 and 1986, a total of 30 of these amendments significantly reduced the rights of those facing criminal charges (Galie and Bopst, 1996).

Over time, American states have amended their constitutions to enable them to address various types of economic concerns, as well as to modify the civil liberty provisions of their foundational documents. Those states that came to view the power of corporate monopolies and centers of wealth as a threat to the public interest, such as the railroads and the banking and insurance industries, continued the Progressive Era efforts of the late 19th century to curb corporate influence with various targeted constitutional amendments. These amendments permitted robust governmental regulation and shifted greater tax burdens on to these interests (Zeigler, 1983). Just prior to and during the New Deal Era, many state constitutions were amended to facilitate various social reforms, particularly in the area of workers’ rights. Some of these efforts included constitutional amendments to permit workers to unionize, states to establish Workers Compensation funds and minimum wage levels, and states to create public agencies to promote public health and safety through the exercise of rights of inspection of private property. These amendments also ensured the protection of child labor through active state oversight (Goodsell, 2004).

Current Trends in State Constitutions

Recent trends in state constitutions reflect an increasing engagement with critical issues such as economic liberty, election integrity, environmental protection, and abortion rights, as states play a pivotal role in addressing topics of national importance within their jurisdictions.

Economic Liberty: The recent decision by the Georgia Supreme Court in Raffensperger v. Jackson is indicative of a burgeoning trend where state constitutions are being used to bolster economic liberties beyond the scope traditionally granted by the federal constitution. In this landmark ruling, Georgia’s constitution was interpreted to impose a stricter standard for justifying occupational licensing laws, requiring them to be “reasonably necessary” to further a legitimate public interest. This legal standard represents a departure from the more lenient federal “rational basis” test and signals a shift towards a more active judicial role in scrutinizing economic regulations at the state level.

This pivotal decision underscores a broader judicial recognition that state constitutions can serve as a reservoir of rights and protections, particularly in the sphere of economic freedoms. By demanding a tangible and direct link between licensing laws and the public interest they purport to serve, the court has laid down a significant marker that could reshape the regulatory landscape. Entrepreneurs and professionals burdened by onerous licensing requirements may find new recourse in state constitutional provisions, potentially igniting a wave of similar judicial reassessments in other states.

The Georgia case is a clear demonstration of how state courts are increasingly willing to diverge from federal interpretations, emboldening them to safeguard individual rights against perceived overreach. It reflects an evolving jurisprudence that could stimulate a reevaluation of economic regulations across the nation, inspiring litigants to appeal to state constitutional protections that align with this emergent philosophy. The decision’s reverberations could lead to a patchwork of state-specific economic rights, profoundly impacting the regulatory environment across various sectors and potentially fostering a climate more conducive to entrepreneurship and economic growth.

Election Integrity: The debate on election integrity has surged to the forefront of American political discourse in recent times. Central to this discourse is the role of state constitutions in safeguarding democratic processes. State constitutions, often seen as the bedrock of local governance, provide a framework for ensuring that elections are fair and equitable. They embody the aspirations of political equality and popular sovereignty, reflecting the will of the people at the most fundamental level of democracy. As such, when there is a concern about election integrity, these foundational documents become particularly vital. They offer a counterbalance to potential legislative overreach, asserting a standard against which new laws and regulations are measured.

Recent developments in various states have put these constitutional protections to the test. Legislation that potentially alters the electoral landscape raises questions about the extent to which such changes are in harmony with constitutional principles. The instance of Georgia’s recent laws is illustrative; these laws have sparked a vigorous debate about their impact on the integrity of the electoral process. Proponents argue that such laws are necessary to safeguard elections and prevent fraud, while opponents see them as veiled attempts to disenfranchise certain voters. Scholars and legal experts at institutions such as the Columbia Law School emphasize the importance of state constitutions not just as historical documents, but as living texts that must be continually interpreted in the light of contemporary challenges. They are the bulwarks that protect individual rights against the ebb and flow of political tides, ensuring that the voice of every eligible voter is heard and that the sanctity of the ballot box is maintained.

Environmental Protection: In an era where environmental concerns have escalated into a global dialogue, individual states within the U.S. are harnessing the power of their constitutions to address these critical issues. The recognition of environmental rights as constitutional rights marks a significant shift in legal paradigms. States such as Montana and Hawaii are leading the way, with their courts interpreting state constitutions as providing not just a general guideline, but a specific, enforceable right to a clean and healthful environment. This progressive interpretation by state courts underscores a broader acknowledgment of the environment as a public trust, where the state is the custodian of the environment for current and future generations.

The landmark decisions in these states reveal a deepening appreciation for environmental protection as an intrinsic value tied to the health and wellbeing of its citizens. This legal trend suggests a departure from treating environmental policy as solely the domain of administrative agencies, towards embedding it deeply within the fundamental law of the land. By framing environmental rights as constitutional rights, these states afford citizens a powerful legal avenue to challenge actions that threaten the environment. It also sets a precedent for environmental justice, recognizing that a healthy environment is a right that benefits all, irrespective of socio-economic status. As states continue to interpret and define these constitutional provisions, the implications for environmental law, public health, and community activism are profound, charting new territories for environmental stewardship and advocacy.

Abortion Rights: The decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in 2022, effectively reversed the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling. The Roe v. Wade decision had established a constitutional right to privacy under the Fourteenth Amendment that protected a woman’s liberty to choose to have an abortion without excessive government restriction. This precedent set by Roe, along with the subsequent Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision in 1992, which introduced the “undue burden” standard for abortion restrictions, had been the foundation of abortion law in the United States for nearly half a century.

In Dobbs, the Supreme Court held that the U.S. Constitution does not confer a right to abortion; Roe and Casey were overturned, and the authority to regulate abortion was returned to the individual states. This meant that the legal status of abortion would be determined by each state, leading to a patchwork of laws ranging from protections of abortion rights to significant restrictions or outright bans on the procedure. The ruling was the culmination of long-standing efforts to challenge Roe v. Wade and has had profound implications for reproductive rights and health care in the United States, prompting extensive legal, political, and social discussions and actions across the country.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade by the U.S. Supreme Court has catalyzed a significant shift in the legal landscape surrounding abortion rights in the United States. With the constitutional protection for abortion no longer recognized at the federal level, state constitutions have emerged as the new frontlines in the battle over these rights. States have gained the autonomy to navigate this contentious issue, leading to a patchwork of laws that either safeguard or severely limit access to abortion. Several states have moved swiftly to amend their constitutions, some embedding protections for reproductive rights, while others have introduced stringent restrictions or near-total bans.

As a result, state courts are finding themselves at the center of complex legal debates, interpreting new constitutional amendments and their implications for health care and legal procedures. The absence of a uniform federal standard has given rise to divergent state-by-state interpretations, with significant consequences for individuals seeking access to reproductive health services. This patchwork approach has not only legal but also profound social and economic implications, affecting the mobility and autonomy of individuals across state lines. The role of state constitutions, therefore, has never been more critical, as they are now the defining instruments that either uphold or undermine the right to abortion, deeply affecting the lives of millions. The ongoing legal challenges and debates continue to highlight the evolving nature of constitutional rights and their interpretation in light of shifting societal and political values.

Constitutionalism: What Can I Do?

Toward the beginning of this chapter we reported some survey data showing very low levels of knowledge among youth concerning the constitution, rights, and civic knowledge in general (see Table 5.1). These results are consistent with other surveys of civic knowledge in the U.S. (e.g., Milner, 2002). According to in the authors of the classic study What Americans Know About Politics and Why it Matters, political scientists Michael Delli Carpini and Scott Keeter convincingly argue that “…democracy functions best when its citizens are politically informed” (1996: 1). Here are two activities where you can test your level of awareness:

1. Take the Intercollegiate Studies Institute “Civic Quiz” on line and see how you fare:

http://www.americancivicliteracy.org/resources/quiz.aspx

2. See how well you would do with the 100 Typical Questions Asked by Immigration and Naturalization Service Examiners for U.S. citizenship:

https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/questions-and-answers/100q.pdf

State Constitutions and Sustainability

As we indicated in the preface, a central theme of this book is the pursuit of sustainability by America’s state and local governments. What role do state constitutions play in state and community sustainability? Are state constitutions to be seen as barriers to necessary societal adaptation, or as active channels for adaptive change in the effective promotion of sustainability and institutional resilience? Some critical observers of state government argue that state constitutions are deeply flawed, and that they have become rigid, time-bound documents reflecting piecemeal changes reflecting no appropriate plan for societal adaptation to change. Given their alleged hidebound nature, these governing documents require evermore amendments so that the states can govern at least somewhat effectively under their ponderous provisions. In adding amendment after amendment, the problem of new potential barriers to change is made worse yet. It follows from this reasoning that there is considerable potential for a state’s constitution to become a barrier to state and local government sustainability. If this is a fair characterization, then it follows that state constitutions have grown into unmanageable documents that inhibit the flexibility required for state and local governments to adapt to major events such as global climate change and rising sea levels in coastal areas. Considering the fact that there have been over 7,000 amendments to state constitutions, some of these amendments may well become potential barriers to effective adaptation.

In reviewing the history of state constitutional amendments and revisions with an objective frame of mind, however, it would seem that the many changes which have been introduced by constitutional amendment were often reasonable responses to the politics and major issues of concern of the time. The constitutional amendments adopted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by-and-large represented alterations that were in keeping with Progressive Era politics, where reformers moved toward the timely professionalization of state and local government and the introduction of new means to promote direct democracy through the initiative process. Later on in the 20th century, the New Deal Era moved state constitutions towards social reform in the same way, often employing the means allowed by the constitutional amendment process (Kelman, 1987).

Thus, one could argue the state constitutional amendment processes themselves neither promote nor bar progress toward community sustainability or resilience, but that history teaches that the political will of the states at any particular time often has been incorporated effectively into state constitutions through the amendment process. In the past, American states have amended their constitution frequently in response to the major political and social movements of the time. As society’s attention moves more fully to meeting the challenge of global climate change and sustainable development, it seems clear from our assessment of the states’ track record of historical adaptation that state constitutions will be able to incorporate appropriate provisions into their respective state constitutions. As demonstrated with California’s Proposition 71 enacted in 2004, if one state can adopt an amendment that has a positive impact on the state, a number of other states will likely follow suit. The California Stem Cell Research and Cures Act established an institute to support stem cell research for the development of life-saving regenerative medical treatments and cures. Such dramatic actions can happen again, where one state’s constitutional amendment can serve as a template for other states to follow.

It should be recalled that there are three basic methods of constitutional amendment available to the states; it is worthwhile to ask at this point which of the three major methods of constitutional change is best suited to promote sustainability? While the constitutional convention would be the most efficient method, allowing a thorough revision of the constitution, the potential of such a tool being used in this age of partisan politics and highly organized special interests is quite remote indeed. In contrast, the legislative amendment method has potential in some states; however, the super-majority of both legislative houses’ requirement may pose a difficult barrier in many states. Lastly, the popular initiative, which is still only available in 18 states, is the most likely method to be used to promote sustainability in American state and local government. A powerful potential tool for change, the popular initiative could be used by state-based grassroots groups to place a single amendment at a time in their constitution — the difficulty being that sufficient voter signatures must be garnered, and the amendment would need to win the popular vote in statewide balloting. With the potential impacts of global climate change becoming more apparent – for example, rising sea levels, more frequent and more violent storms, earlier snowmelt, extended droughts, raging wildfires and fires in heavily forested areas – some states with the initiative process are likely to see ballot initiatives directed toward the promotion of sustainable development and local community resilience into their constitutional fabric (Bowler et al., 1998). The non-initiative states will be witness to these developments in other states, and are likely to take up their own versions of these initiatives through legislative action. It is a safe bet that American states will be at the forefront of “thinking globally and acting locally” to confront the challenges of sustainable development, and that a likely goal of the advocates of sustainability will be achieving timely amendments to state constitutions where this avenue for change exists (Burby and May, 1997).

The New “Constitutions” of Sustainable Governance

While state constitutions are important vehicles for promoting the value and institutional shifts associated with sustainable governance, the formal constitution may not move quickly enough in response to changing needs or conditions. Traditional governance viewed many aspects of the constitution and institutional arrangements as steady and continuous. Sustainable governance requires that the constitution be viewed as a general governing structure; however, it is clear that the actual day-to-day process of governance operates as a form of organized chaos, responding to changing conditions, meeting ever-changing demands, and responding to rapid technological change and scientific discovery.

The new “constitutions” of sustainable governance have actually been around for quite a while, but they are playing an increasingly prominent role in sustainability. The intergovernmental agreement (IGA) and the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) are two such important legal/institutional tools available to promote sustainability in the coming years. Intergovernmental agreements are directly related to federalism and multi-state arrangements within the American federal system. Intergovernmentalism might involve national-state or national-local agreements or inter-state and inter-local agreements of various kinds. IGAs often recognize the inter-jurisdictional nature of many problems (e.g., the drug trade, human trafficking, rapid diffusion of communicable diseases, acid rain deposition, etc.), with sustainability being one very important current dilemma. In terms of sustainability, the basic question faced by any level of government is: “Can we maintain the existing conditions or achieve an even higher quality of life and provide basic services to future generations of citizens?” Achieving a positive outcome may involve governments working together in a manner in which all achieve positive results and no party loses. IGAs are an attempt to achieve this positive “win-win” outcome for a reasonable cost, while retaining the benefits of responsiveness and the unique nature of each participant governing body.

Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) are legal documents comparable to contracts that define the responsibilities and constraints faced by each governmental party engaged in a collective effort to achieve a shared policy goal. MOUs define goals and responsibilities of each participating government, oftentimes focusing on particular agencies within these governments. In an era of rapid response to emerging troublesome problems of sustainability, the Service Legal Agreement (SLA) — a specific form of MOU — defines the nature of response by each participating government and each government agency to include agreed-upon forms of intergovernmental and interagency planning and communication.

The proliferation of IGAs, MOUs, and SLAs in recent years is in part an appropriate recognition of the need for sustainable governance networks which respond to change rapidly, effectively, and efficiently while maintaining the higher-order values of the formal constitutional arrangements of participating jurisdictions. This capacity to invent new forms of inter-agency relationships among the states and their respective local governments is very important, not only because coordinated action is facilitated, but because this process allows citizens to take an active part in their own state and local governments. Sound research instructs that there is a strong association between level of citizen engagement and scale of government (Dahl and Tufte, 1973); if communities were to pass all problems to the national government for resolution, they would likely risk an even greater disengagement of citizens than currently occurring in state and local governments.

Conclusion

State constitutions are a very important aspect of American state and local government because they set forth the supreme law of the state, only subservient to the U.S. Constitution where there is direct federal authority to act. Among other things, state constitutions establish procedures for policy-making, define the structure of state and local government, set the conditions for inter-state and multi-state compacts, set forth requirements for public office, specify state obligations to citizens, enshrine principles of governance, determine the responsibilities of local governments, establish voting rights and determine how elections are to be conducted, and specify processes for constitutional change. These are all important functions at any time, but they are of great importance in a time when the challenges of sustainability will confront the leaders of our state and local governments.

The most important function of state constitutions, however, is to establish the rule of law and enforce the principle of limited government. All fifty state constitutions provide protections for individual liberty, and freedom of speech and association. Most state constitutions recognize a right to privacy. While these rights mostly reiterate protections provided in the U.S. Constitution, many state constitutions even extend right-based protections for their citizens that go beyond what is found in the national constitution as it is read by the U.S. Supreme Court. State constitutions may offer this same extension for the protection of citizens and their property in the area of sustainable development and local community resilience. Scholars who have studied the capacity for Americans to gain an understanding of difficult public policy issues and in time develop attitudes and policy preferences in line with needed change provide reason for optimism in this regard (Page and Shapiro, 2010). There are early signs of change in the public’s understanding of sustainability noted in this chapter, and it is likely that much more change will be handled by government at the state level as spelled-out in amendments of state constitutions.

Terms

- Civil Liberties

- Constitutional Convention

- Constitutional Democracy

- Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA)

- Jacksonian Democracy

- Judicial Federalism

- Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)

- New Deal Era

- Oregon System

- Progressive Era

- Republican Government

- Reserved Powers

- Special Purpose Government

- Supremacy Clause

Discussion Questions

- What are the primary purposes of state constitutions? How are they both similar to and different from the U.S. Constitution?

- What are some of the guiding principles found in state governments? From your own point of view, what types of guiding principles belong and do not belong in state constitutions?

- What are the various procedures available to change constitutions? What methods are available in your state to change the constitution? What is your assessment of the degree to which the states have established an historical track record of adaptability to change in their pattern of constitutional amendments?

- How do you feel about the “Oregon System” in terms of state constitutional amendments? What are some of the positive and negative aspects of allowing citizens to directly amen state constitutions through general election ballot measures?

References

Alvarez, R. M., and Brehm, J. (2002). Hard choices, easy answers. Princeton University Press.

Benjamin, G., and Gais, T. (1996). Constitutional convention phobia. Hofstra Law and Policy Symposium, 53.

Blaustein, A. (1990). Contemporary trends in constitution writing. In Elazar, D. (Ed.), Constitutionalism: The Israeli and American experiences. University Press of America.

Boorstin, D. J. (1953). The genius of American politics. University of Chicago Press.

Bowler, S., Donovan, T., and Tolbert, C. J. (Eds.). (1998). Citizens as legislators: Direct democracy in the United States. Ohio State University Press.

Burby, R. J., and May, P. J. (1997). Making governments plan: State experiments in managing land use. The Johns Hopkins Press.

Council of State Governments. (Ed.). (2006). The book of the states, 2006. The Council of State Governments.

Cronin, T. E. (1989). Direct democracy: The politics of initiative, referendum, and recall. Harvard University Press.

Dahl, R. A., and Tufte, E. R. (1973). Size and democracy. Stanford University Press.

Dinan, J. (2006). State Constitutional Developments in 2005. In The book of the states, 2006. The Council of State Governments.

Friedman, L. M. (1988). State constitutions in historical perspective. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 496, 33-42.

Galie, P. J., and Bopst, C. (1996). Changing state constitutions: Dual constitutionalism and the amending process. Hofstra Law and Policy Symposium, 27.

Goodsell, C. T. (2004). The case for bureaucracy: A public administration polemic (4th ed.). Congressional Quarterly Press.

Hammons, C. W. (1999). Was James Madison wrong? Rethinking the American preference for short, framework-oriented constitutions. American Political Science Review, 93, 837-849.

Kelman, S. (1987). Making public policy: A hopeful view of American government. Basic Books.

Lutz, D. S. (1994). Toward a theory of constitutional amendment. American Political Science Review, 88, 355-370.

Maddex, R. L. (2006). State constitutions of the United States (2nd ed.). Congressional Quarterly.

Oregon Blue Book. (2024). Initiative, referendum and recall introduction. Retrieved from http://bluebook.state.or.us/state/elections/elections09.htm

Oregon Blue Book. (2007). Constitution of Oregon: 2005 version. Retrieved from http://bluebook.state.or.us/state/constitution/constitution15.htm

Page, B. I., and Shapiro, R. Y. (2010). The rational public: Fifty years of trends in Americans’ policy preferences. University of Chicago Press.

Seidelman, R., and Harpham, E. J. (1985). Disenchanted realists: Political science and the American crisis, 1884-1984. State University of New York Press.

Stoner, J. R. (1992). Common law and liberal theory: Coke, Hobbes, and the origins of American constitutionalism. University Press of Kansas.

Swarthout, J. M., and Gervais, K. R. (1969). Oregon: Political experiment station. Politics in the American West, 296-325.

Tarr, G. A. (1998). Understanding state constitutions. Princeton University Press.

Utah State Law Library (n.d.). Research guide: Utah constitution. Retrieved from www.utcourts.gov/lawlibrary/docs/constitution_website.pdf

Wormuth, F. D. (1949). The Origins of modern constitutionalism. Harper and Brothers.

A system of governance premised on the belief that government can and should be legally limited in its powers, and that its rightful exercise of authority depends on observing these limitations established as the rule of law.

The most traditional method to propose a new state constitution or revise an existing constitution, the initiation of which requires a formal call from the legislature; this is an action which all 50 state legislatures and the District of Columbia are empowered to do.

The clause establishing the Constitution, Federal Statutes, and U.S. treaties as the supreme law of the land, mandating that state judges uphold them, even if state laws or constitutions conflict.