Chapter 7: Legislatures

Introduction

A legislature is an officially elected assembly formed to make laws for a political unit such as a nation, a state, or a local government. The genesis of legislatures traces back to the medieval period, when “Althing” (a Nordic word for ‘general assembly’) was established in Iceland and a uniform code of laws was proclaimed. In more contemporary times, there are various types of legislative forms, including the two most common categories of legislatures — the presidential style systems featuring separation of powers and the parliamentary style systems featuring integration of powers (Liphart, 1992; Weaver and Rockman, 1993). As discussed in the previous chapter, in political systems reflecting a separation of powers philosophy of governance, a policy adoption vs. policy administration and implementation dichotomy exists separating the legislative branch and the executive branch; in line with this demarcation of responsibilities, governmental powers are fairly clearly separated in law and in practice (Frederickson and Smith, 2003). In contrast, in political systems reflecting an integration of powers philosophy of governance, members of the executive branch are selected from and are held directly accountable to the legislative branch (Woodhouse, 1994). In the U.S., state legislatures are presidential style bodies which are primarily in charge of making laws of general purpose and universal application for the respective states, with governors being responsible for the “faithful execution” of state laws. At the local level both general-purpose governments and single-purpose governments are present. The former provides a wide range of services and serves a diversity of functions, while the latter carries out a specific function such as education, hospital services, the provision of utilities, the irrigation of farmlands, or the provision of transportation services, for example. There are a variety of legislative structures used in local governments, including boards of county commissioners, city councils, school district boards, and a wide variety of more specialized elective boards and commissions that will be discussed in this chapter.

The topics covered in this chapter include:

- the functions of legislatures.

- noteworthy variation in the ways state legislatures operate.

- legislatures in general-purpose local governments.

- legislatures in single-purpose local governments.

- the critical legislative role in promoting sustainability.

- current trends in state and local government legislatures.

State Legislatures

All the U.S. states have a popularly elected legislative branch, and each state constitution specifies the essential features of the composition and method of organization of state legislative bodies. State legislatures are the primary lawmaking bodies of American government, and they are, generally speaking, quite similar in structure to the U.S. Congress. The legislature in all cases is a multi-member body of popularly elected representatives. In forty-nine states the legislature is divided into two houses, generally a Senate and a House of Representatives, just as is the U.S. Congress. Only Nebraska features a unicameral (one chamber) legislature. The “upper house” (Senate) is usually significantly smaller than the lower house, which in most states is called the “House of Representatives.” Senators are most often elected for four-year terms, but some states elect their Senators every two years. State representatives usually are elected for two-year terms. In many states constitutional term limits control the number of terms – consecutive or otherwise – which a legislator is allowed to serve. Most states dictate that each legislative electoral district will elect only one representative and only one senator. However, eight states do allow multi-member districts wherein voters elect more than one representative for the lower house of the state legislature.

Nearly all the American states adopted the bicameral legislature in major part because they wished to allow landowners a major voice in government disproportionate to their number in the electorate. Senators were once elected by county or groups of counties as opposed to population, in a manner very similar to the U. S. Senate’s apportionment of two Senators per state, regardless of the size of its population. This apportionment of seats in the upper chamber allowed residents in rural and sparsely populated areas of a state to exercise significantly more influence than urban residents within American state legislatures. In 1962 (Baker v. Carr) and again in 1964 (Reynolds v. Sims), however, the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear cases wherein it was argued that the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution required that the principle of “one person, one vote” should apply to both houses of American state legislatures. It was reasoned by lawyers arguing for a fundamental change in the organization of state legislatures that the U.S. Congress organized membership around a principle of representation by geography because it is a federal system in which the individual states pre-existed the establishment of the United States of American. In the case of the U.S. states, however, they are each unitary governments wherein all citizens, regardless of where they reside (city, suburb, or rural area), are entitled to equal representation.

The U.S. Supreme Court determined in these landmark cases that both chambers of American state legislatures must be based upon population alone. The initial result of these decisions was that state legislatures redrew their upper chamber legislative district lines to reflect population, causing many more legislators to be representing urban areas in upper chambers of American state governments. These legislative districts must be redistricted every ten years when the U.S. Census is taken to assure that they conform to the equal representation [“one person, one vote”] standard as closely as possible. While the manifest intent of redistricting is to ensure equal representation in government, the process of drawing legislative district lines is the responsibility of state legislatures and tends to become highly politicized and partisan in nature in those states which do not establish an independent, bipartisan body to carry out redistricting. In fact, in a number of states legislative district lines are commonly redrawn to maximize the strength of the majority party and weaken the minority party in a process commonly known as gerrymandering. This process entails concentrating the minority party’s voters in as few districts as possible, and distributing the majority party’s voters in such a way that they are likely to prevail in as many legislative districts as possible.

As the process of gerrymandering indicates, political parties play a very important role in state legislatures. The majority party typically organizes the election of the leader of the lower house (the House Speaker in most cases), and in most states the leader of the upper house (typically the Senate Majority Leader) is put into office on the basis of a partisan vote. The party leadership in both chambers generally appoints legislators to their committee assignments, designates committee chairs in the case of the majority party, and typically controls floor activity fairly tightly with a party whip. As a result of these decisions influenced greatly by the majority political party, a relatively small number of key legislators in control of a legislative house typically dominate the agenda and content of bills heard during any legislative session.

The powers of state legislatures universally include modifying existing laws and making new statutes, developing the state government’s budget (Clarke, 1998), confirming the executive appointments brought before the legislature (Hamm and Robertson, 1981), impeaching governors and removing from office other members of the executive branch (Gerhardt, 2000). All these powers and associated activities can be assigned to one of the three major functions performed by state legislators singularly and state legislatures collectively: representation, lawmaking, and balancing the power of the executive (or oversight).

Representation

A major role of a state legislator is to represent the needs and concerns of the people residing in her and his legislative district. Since each legislator is responsible to a relatively small number of constituents coming from a specific geographical area, they can address concerns that are not as apparent to statewide officials such as the Governor or State Attorney General. This attention to localized needs can lead to intense debate over conflicting values when, for example, representatives of rural, conservative communities are forced to compromise with the interests represented by urban legislators representing liberal constituents.

Legislators also represent the interests of their constituents beyond the formal law-making process. Legislators are often enlisted to make a phone call or write a letter on behalf of a citizen who needs help getting a personal issue addressed or expedited by the state bureaucracy. Research conducted by political scientists has shown that such constituency service pays significant dividends at re-election time, with voters looking favorably on helpful legislators by either volunteering for campaign work or contributing money to re-election campaigns. Key components of sustainability as addressed in the literature include the development of civil society, active representation by elected officials, and the maintenance of continuous interaction between citizens and representatives. In this regard, how legislators interact with their constituents is an important part of the promotion of sustainability in those communities where efforts to promote sustainability require some level of state approval and/or financial support.

The process of representation works at two distinct levels. First, at an individual representative’s level there is a connection between the legislators and the districts from which they are elected. And secondly — as a unit — the legislature pursues policies that reflect the statewide interests and preferences of citizens (Rosenthal, 2004). The process of representation, from the perspective of political scientists, consists of four principal components: maintaining communications with constituents; demonstrating policy responsiveness by reflecting the needs of one’s constituency in one’s votes on bills and budgets; affecting the allocation of resources across elective districts; and providing individualized service to constituents (Barber, 1983; Jewell, 1982).

Another way to think about representation is in terms of the socio-demographic and gender composition of state and local legislative bodies. Many observers argue that legislative bodies should, to some significant extent, mirror the public they represent — in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, and such — to adequately represent the public at large. In this regard, it should be noted, “in the past, political scientists have convincingly demonstrated that race and gender matter in political representation” (Bratton, 2002). Research has consistently shown that in state legislatures “Black legislators sponsor a higher number of Black interest measures and female legislators sponsor a higher number of women’s interest measures” when compared to white men (Bratton, 2002).

In general, “female state legislators are reported to be more liberal than men, even when controlling for party membership, and female state legislators are more concerned with feminist issues than their male counterparts” (Barrett, 1995). Research has also found that black women legislators are similar to white women legislators in terms of their support for women’s issues — such as affirmative action, comparable worth, public support for day care, and many other issues. As with black male legislators, black women legislators tend to be strong supporters of minority targeted policies such as education, health care, and job creation-oriented economic development (Barrett, 1995: 223). However, research has also found that women legislators are generally as likely as their male counterparts to achieve passage of the legislation they introduce, whereas black legislators are significantly less likely than their white counterparts to get legislation they introduce enacted into law (Barrett, 1995).

In terms of the actual representation of women and minorities in state and local legislatures, there has been a noteworthy increase in numbers over the last several decades. The Center for American Women and Politics, an organization that systematically tracks the number of women in elected office, reports the following in terms of women serving in state legislatures across the country. In 1971, women comprised 4.5 percent of state legislators. As of 2024, women's representation in state legislatures across the United States has indeed reached a historical high, with women holding 32.9% of the nation’s 7,386 state legislature seats. This increase highlights significant and continuous progress in female representation in politics over the years (Center for Women in Politics, 2024). The states leading in gender representation showcase impressive figures: Nevada at 60.3%, Arizona at 50.0%, and Colorado at 49.0%, each setting benchmarks for gender parity in legislative roles. These states exemplify progressive political environments that actively promote diversity and inclusion within their governance structures (Center for Women in Politics, 2024).

Conversely, states like West Virginia, Tennessee, and Mississippi report the lowest percentages, with 11.9%, 15.2%, and 15.5%, respectively. These figures indicate areas where traditional political cultures might still pose challenges to gender parity in politics. The disparities between these states and the leaders in female legislative representation point to the varied impact of local political cultures, electoral systems, and recruitment practices on the promotion of women in politics (Center for Women ion Politics, 2024).

The broader trend of increasing women's participation in state legislatures, more than quintupling since 1971, reflects a steady, though gradual, push towards gender parity at the state level. This trend is not just a reflection of changing societal norms regarding women in leadership but is also the result of targeted efforts by advocacy groups, policy changes, and a growing recognition of the benefits of diverse legislative bodies (Center for Women in Politics, 2024). Such statistics are crucial as they not only reflect the current state of political representation but also influence future policies related to gender equality, providing a clearer picture of where focused efforts are needed to promote gender parity in politics across all states.

As of 2024, the landscape of African American leadership in U.S. cities has evolved significantly. Currently, 14 of the nation's 50 most populous cities are led by Black mayors. This marks a substantial presence and influence of African American leaders in major urban centers across the country, reflecting a notable trend in the increasing diversity of city-level governance (Booker, 2023). The African American Mayors Association (AAMA) has been a pivotal platform for these leaders, providing a forum for collaboration and advocacy on public policies that impact the vitality and sustainability of cities. This organization, exclusive to African American mayors, aims to empower local leaders for the benefit of their citizens, highlighting the significant role these mayors play in shaping the urban landscape.

In terms of political culture and its impact on minority representation in state and local legislatures, traditional cultural attitudes still play a substantial role. States with a more traditional political culture may have less favorable views towards minority and female candidates compared to states with more progressive cultures. This affects the likelihood of minorities and women running for office, their recruitment by political parties, and their success at the polls. Moreover, institutional arrangements like high incumbent reelection rates and the structure of electoral districts also influence the diversity of legislatures, where multi-member districts tend to be more inclusive (The White House, 2023).

The increasing presence of African American mayors and greater diversity in state and local legislatures highlights significant progress towards inclusivity in U.S. political systems. This change not only improves representation but also enriches policy discussions with a wider range of perspectives and experiences, crucial for addressing the needs of a diverse populace. Cities such as Los Angeles and New York, led by African American mayors, benefit from leadership that brings a deep understanding of multi-ethnic communities and their unique challenges (Booker, 2023).

These strides in representation are empowering for communities which have been historically underrepresented in political spheres and can lead to more equitable policy outcomes. For example, having African American mayors in significant urban centers allows for policies that directly tackle issues such as urban poverty, affordable housing, and education disparities, adverse conditions which often disproportionately affect minority populations (Booker, 2023; The White House, 2023). However, the journey towards truly inclusive governance remains ongoing. Challenges such as cultural biases that view politics as unsuitable for certain demographics or institutional hurdles such as the configuration of electoral districts continue to impede further progress. These challenges necessitate ongoing efforts to reform political institutions and reshape societal attitudes to create a truly equitable political landscape.

Addressing the challenges related to minority and women representation in political structures requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses both immediate actions and strategic long-term initiatives. In the short term, efforts there needs to be a focus on enhancing the recruitment and support for minority candidates. This involves not only identifying potential candidates from diverse backgrounds, but then also providing them with the necessary resources and support networks to run successful campaigns. Organizations and political parties play quite crucial roles here, offering training sessions, mentoring, funding, and ongoing consultation to prepare candidates for the complexities of electoral politics.

For the long term, broader societal changes are essential. This includes changing public perceptions about the roles and capabilities of minority leaders through education and positive media representation, both of which can help break down stereotypes and encourage a more inclusive view of leadership. Additionally, legal reforms are crucial to ensure fair representation. Amending laws that govern electoral processes—such as those related to districting, voting rights, and campaign finance—can help remove structural barriers that tend to disproportionately affect minority candidates and impact their ability to win elections and influence governance effectively (McGregor et al., 2017; Rao, 2005; Spicer et al., 2017).

Those that favor legislative diversity have proposed a variety of electoral mechanisms to increase the proportion of women and racial minorities serving in state and local legislative bodies. Some advocates have suggested the broadened adoption of term limits because the current re-election rate of incumbents is very high, while others have suggested the creation of majority Black or Latino districts by carefully drawing election district lines to favor minority districts (Darcy et al., 1987). However, this latter approach to the promotion of diversity in legislative bodies was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Miller v. Johnson 515 U.S. 900 (1995) and Shaw v. Hunt 517 U.S. 899 (1996).

However, while there are proponents of greater representation of minorities in elected office, several states have enacted what might be considered gerrymandered electoral districts to minimize minority representation. Recent Supreme Court cases have addressed issues of gerrymandering that disproportionately affect minority populations, often under the Voting Rights Act's Section 2. Here are some notable examples:

- Allen v. Milligan (formerly Merrill v. Milligan) – This case challenged Alabama's congressional redistricting. Plaintiffs argued that the state's map violated the Voting Rights Act by failing to create a second Black majority district despite significant demographic changes. The Supreme Court heard arguments suggesting that Alabama's drawing of district boundaries diluted Black voters' influence, a claim rooted in the historical division of the "Black Belt" area among multiple districts to minimize Black voters' electoral influence (Li and Rudensky, 2022).

- Georgia State Conference of the NAACP v. Georgia – In this ongoing case, plaintiffs contend that Georgia's redistricting maps are racial gerrymanders violating both the 14th Amendment and Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. They argue that the maps dilute Black voting power by packing Black voters into specific districts while spreading them thinly across others to minimize their electoral impact (Greenberg, 2023).

- Alexander v. South Carolina – After the South Carolina legislature redrew congressional maps, over 30,000 Black residents were moved from one district to another, significantly reducing the percentage of Black voters in their original districts. This redistricting was challenged as a racial gerrymander. The case highlighted the tension between claims of partisan and racial gerrymandering, with the state arguing that the changes were politically but not racially motivated (Green, 2023).

Legislative Lawmaking

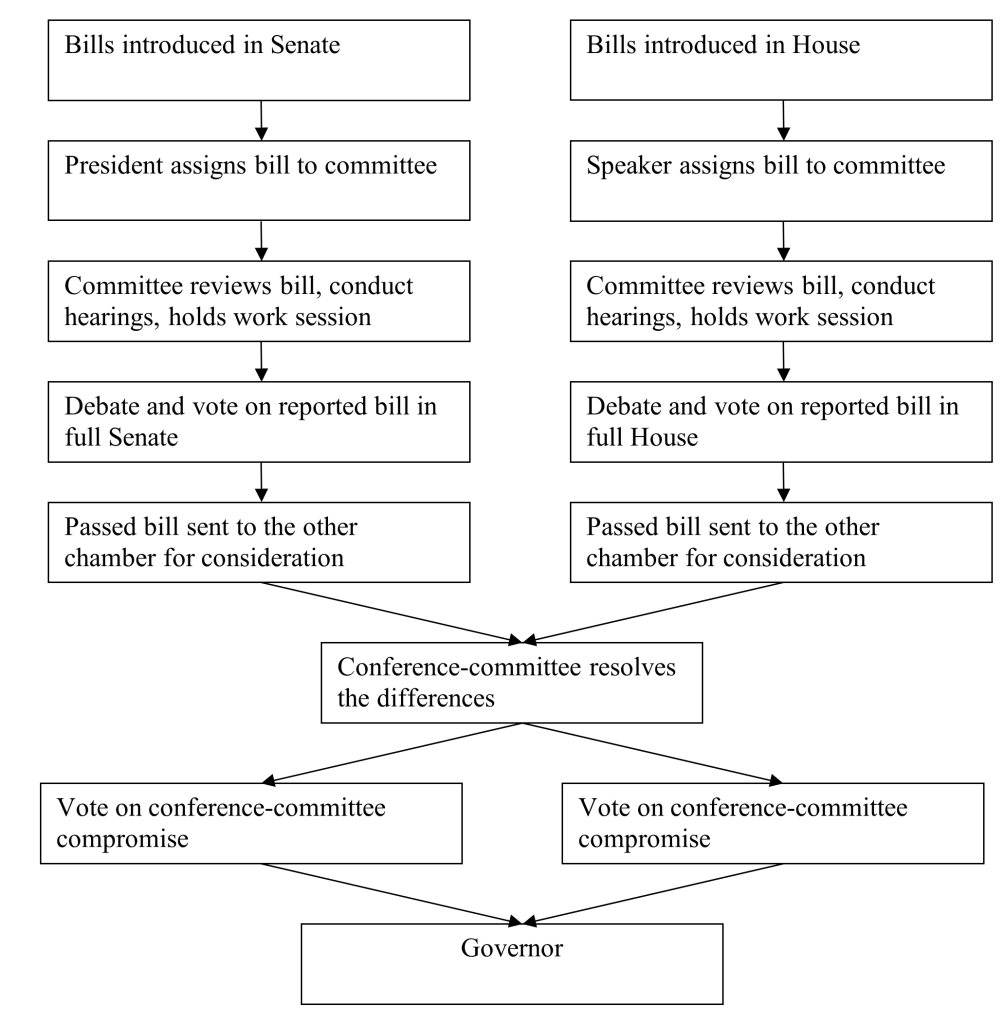

Policymaking is accomplished through the introduction and passage of bills that eventually become law. The process usually begins with the introduction of bills in either house of the legislature. While bills must be introduced by a legislator (sponsor), they usually have been crafted by a governor, an attorney general, a public agency, or an interest group with appropriate legal expertise. Once a legislator chooses to introduce the legislation, other fellow representatives and senators can sign on as co-sponsors, increasing the likelihood the bill will survive scrutiny in legislative committees. New bills are referred to policy committees in their chamber of origin. The committee chair decides whether to hold a hearing on the bill, and whether to hold a committee vote on it. Bills are frequently amended in committee before they are voted out. If the vote in committee is favorable, the bill is forwarded to a rules committee that makes decisions on which bills are placed on the calendar of the chamber to be heard. Bills can be amended once more on the floor, and if passed they are sent to the other chamber for its consideration. If the second chamber amends the bill and passes it, then members of both chambers go to a “conference committee” to determine if the differences between the two versions of the bill can be reconciled. If a compromise is achieved, the new bill is sent back to the floor of the Senate and House for a final vote. If the conference committee bill is approved in both houses of the legislature it is then sent to the governor where it will be signed into law, vetoed, or remain unsigned. If a bill is vetoed by the governor, it can return to the legislature for a possible veto override by a “supermajority” (usually two-thirds vote) in both chambers. If a governor neither signs nor vetoes a bill, it will become law in two-thirds of the states; in the remaining third of the states inaction by the governor is referred to as a “pocket veto” and the bill dies (see figure 7.1). Another way for a bill to become law in some states is a legislative referral, an action by the legislature and the governor that places the legislation on the ballot for voters to decide approval or disapproval.

Balancing the Power of the Executive

In a separation of powers governmental system, the three branches of government are expected to share power rather than allowing one branch to have disproportionate power over the others. This arrangement of governmental powers has been commonly known as the checks and balances system, a particular vision of governmental design enshrined in the U.S. Constitution by the Founding Fathers. The third principal role a legislature plays, therefore, is balancing the power of the executive branch. This balancing role can be achieved by performing legislative oversight that involves the legislature’s review and evaluation of selected activities of the executive branch and exercising the “power of the purse” – that is, carrying out the responsibility of developing the state budget. In American government no funds can be spent by an executive agency unless an express allocation is made by a legislative enactment (the budget is set in a bill enacted into law just as any other statute). A main reason for state legislatures to conduct oversight is that “it has a duty to ensure existing programs are implemented and administered efficiently, effectively, and in a manner consistent with legislative intent” (Ohio Legislative Service Commission, 2009). The job of exercising legislative oversight is carried out by a combination of standing committees, select committees, and task forces. In Ohio, for example, three such important oversight committees are the Joint Legislative Committee on Health Care Oversight, the Joint Legislative Committee on Medicaid Technology and Reform, and the Turnpike Legislative Review Committee composed of members of both chambers of the state legislature (Ohio Legislative Service Commission, 2007). Common forms of oversight activities include periodic review of administrative rules, the enactment of sunset provisions in legislation, the passage of legislation calling for fact finding studies into particular problems or existing programs, the engagement in active fiscal oversight and the provision of advice to executive agencies, and the granting of consent to gubernatorial appointments.

State legislatures assume the role of oversight to assure that laws are being implemented efficiently and effectively in the manner originally intended by the legislature. The legislature often evaluates the executive branch’s policy and programs through the employment of policy analysts and auditors working for legislative committees. These analysts and auditors attempt to assess progress toward the objectives and goals of policies and agencies reflecting the original intent of the legislation. The use of legislative policy analyses and audits has been credited with increasing efficiency and effectiveness in state government, thereby saving taxpayers money and improving program performance.

In the U.S. legislatures periodically review the rules and regulations employed by the executive branch in order to determine whether the intent of the law is being realized. This review process often accompanies budget hearings and ultimate budget approval for state agencies. If the legislature determines that an agency’s rules and regulations are unsatisfactory, they can insist that the rules be modified or suspended; in some cases the legislature retains the right to discontinue support for a program if, in its judgment, the agency in question is not following legislative intent or is determined to have failed to meet the goals set for it. Some states have determined that the “legislative veto” (an action of constraint upon a public agency by a legislature after legislation has been placed into law) is an unlawful violation of the separation of powers. Even without explicitly revoking a rule or regulation by direct action of the legislature after a law has been duly enacted, the legislature can exert great influence over previously enacted statutes by reducing the agency’s budgetary allotment to encourage more faithful compliance with legislative wishes.

Sunset laws are those pieces of legislation featuring a built-in expiration date for a statute. Legislation of this nature allows the legislature to review, implement changes in, or terminate a program simply by not renewing an existing law. While sunset laws ensure the bureaucracy will be subjected to periodic review, the process of review is often time-consuming, can be quite costly, but only rarely results in the termination of a program. Bowman and Kearney state in this regard, “sunset reviews are said to increase agency compliance with legislative intent . . . [but] only 13 percent of the agencies reviewed are eventually terminated, thus making termination more of a threat than an objective reality” (Bowman and Kearney, 2005).

The review and control of state (and federal “pass through”) funds is one of the most significant powers exercised by state legislatures. By holding the purse strings at both the state and federal level, the independence of the legislative branch ensures that the bureaucracy and executive branch agency leadership remains quite dependent upon legislative support. Thus, ongoing oversight is permitted, and the executive branch is prevented from becoming unresponsive to lawmakers and their constituencies. Furthermore, by reviewing and controlling federal funds given to the state through major intergovernmental programs such as interstate transportation, environmental regulation, Medicaid, etc., legislators are aware of how that federal government transfer money is being spent by the executive branch. Importantly, citizens who wish to know how those federal funds are being spent in their state and localities can contact their legislator and request an accounting. This type of constituent service is an important part of legislative representation. In the area of the promotion of sustainability, your state legislator should be able to provide you with specific, timely information concerning what federal and state programs are in place to address sustainability concerns such as wind farm development, solar energy generation by homes and businesses, availability of electric vehicle charging stations, etc.

Variation Among State Legislatures

State legislatures vary across the country in terms of their official names, the length of time they stay in session, the number of legislative districts they use, their party affiliations, and the way they operate. For example, state legislatures in most states are called “Legislatures;” for example, the Alabama Legislature, the Oklahoma Legislature, the Nevada Legislature, and Montana State Legislature are common names. In some states, however, the state legislature is referred to as the “General Assembly,” such as the Virginia General Assembly and the Pennsylvania General Assembly. In the states of Massachusetts and New Hampshire the term “General Court” is used to designate the state legislative branch. For bicameral state legislative bodies, the upper house is most typically called the “Senate,” but the terms used for the lower house vary widely across the states (see Table 7.1). Historically, most of the original American colonies were governed by unicameral legislative systems until a gradual process of adoption of bicameralism started and picked up momentum. The bicameralism movement was based on respect for the British model of bicameralism of the House of Lords and the House of Commons (Tsebelis and Money, 1997). Today, as noted previously, virtually all (49) state legislatures in the U.S. are bicameral, and only Nebraska has maintained a unicameral legislature (see Table 7.2).

Table 7.1 State Legislative Houses

| State | Both Bodies | Upper House | Lower House |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Alaska | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Arizona | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Arkansas | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| California | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| Colorado | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Connecticut | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Delaware | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Florida | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Georgia | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Hawaii | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Idaho | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Illinois | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Indiana | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Iowa | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Kansas | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Kentucky | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Louisiana | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Maine | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Maryland | General Assembly | Senate | House of Delegates |

| Massachusetts | General Court | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Michigan | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Minnesota | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Mississippi | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Missouri | Jefferson City | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Montana | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Nebraska | Legislature | - | - |

| Nevada | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| New Hampshire | General Court | Senate | House of Representatives |

| New Jersey | Legislature | Senate | General Assembly |

| New Mexico | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| New York | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| North Carolina | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| North Dakota | Legislative Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Ohio | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Oklahoma | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Oregon | Legislative Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Pennsylvania | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Rhode Island | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| South Carolina | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| South Dakota | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Tennessee | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Texas | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Utah | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Vermont | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Virginia | General Assembly | Senate | House of Delegates |

| Washington | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| West Virginia | Legislature | Senate | House of Delegates |

| Wisconsin | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| Wyoming | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

Table 7.2 Unicameral Legislature and Bicameral Legislature

| Indicators | Unicameral Legislature | Bicameral Legislature |

|---|---|---|

| Representation

Responsiveness to the Majority Responsiveness to Diverse and Minority Interests Responsiveness to Powerful Interests |

A citizen has one representative.

Favors rule by the majority. Deeper understanding of all various interests. ‘Almost heaven’ for the special lobbyists. |

A citizen has two respective representatives.

Bicameral deliberation. Gives voice to disparate points of views. Hard for lobbyists to affect legislative activities. |

| Legislative Stability | Not necessarily volatile | Maybe more stable |

| Procedural Simplicity | More | Less |

| Authority of the Legislators | Authority of a legislator is not shared. | Authority of a legislator is shared. |

| Concentration of Power within the Legislature | Concentrates power in one house | Concentrates power in a few members |

| Quality of Decision-Making | Promotes quality by deliberate, careful decision-making. | Promotes quality by slowing decision making, by having a second thought, and by requiring approval by two chambers. |

| Efficiency and Economy | Maybe more efficient in conducting its business and less costly to operate. | May require more cost, but also generate more benefits. |

Another difference between state legislatures concerns time status — some states have full-time legislatures meeting frequently on an annual basis, while other states have part-time legislatures that meet biannually and for a limited time. Many rural states tend to have a part-time legislature, while the states with larger populations are likely to have full-time legislatures. Texas is an exception in this regard, with the second largest population and a part-time legislature. The National Council of State Legislatures has categorized the 50 state legislatures into three basic groups: full-time legislatures, hybrid legislatures, and part-time legislatures. Full-time legislatures “…require the most time of legislators, usually 80 percent or more of a full-time job” (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021). These legislatures typically feature large numbers of legislative staffers and their members are usually paid salaries sufficient to make a decent living. Full time legislatures are typically found in the states with highly urbanized populations (see Tables 7.3).

Table 7.3 State Legislature Types

| Full-Time | Hybrid | Part-Time |

|---|---|---|

| California | Alabama | Georgia |

| Florida | Alaska | Idaho |

| Illinois | Arizona | Indiana |

| Massachusetts | Arkansas | Kansas |

| New Jersey | Colorado | Maine |

| Michigan | Connecticut | Mississippi |

| New York | Delaware | Montana |

| Ohio | Hawaii | Nevada |

| Pennsylvania | Iowa | New Hampshire |

| Wisconsin | Kentucky | New Mexico |

| Louisiana | North Dakota | |

| Maryland | Rhode Island | |

| Minnesota | South Dakota | |

| Missouri | Utah | |

| Nebraska | Vermont | |

| North Carolina | West Virginia | |

| Oklahoma | Wyoming | |

| Oregon | ||

| South Carolina | ||

| Tennessee | ||

| Texas | ||

| Virginia | ||

| Washington |

Legislators elected to hybrid legislatures “…typically say that they spend more than two-thirds of a full-time job being legislators” and their salaries are noticeably higher than part-time legislatures, but somewhat lower than those of members of full-time legislatures. Salaries are typically not sufficient to make a living on legislative pay alone, so additional outside employment is common among these state lawmakers. Hybrid legislatures tend to have intermediate-sized staffs, and they are typically found in states with moderate-sized populations.

Lawmakers in part-time legislatures generally spend “…the equivalent of half of a full-time job doing legislative work. The compensation they receive for this work is quite low and requires them to have other sources of income in order to make a living” (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021). Part-time legislatures are often called “citizen legislatures” and are most often found in rural states with relatively small populations. The legislative staff available to lawmakers in these states is typically rather small.

State legislatures are also diverse in terms of their size and their party composition. Legislators prefer policies that favor the preferences of voters in individual districts, and thus the size of a district matters when considering the implications of certain policies. Table 7.4 shows the number of seats in state upper and lower houses. While some economists have argued that larger legislatures are less efficient and prone to conflict because “…cooperation cannot be sustained in large legislatures,” there has been little empirical research on this topic (Koppel, 2004).

Table 7.4 Seats in Senates and Houses

| State | Seats in Senate | Seats in Houses |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 35 | 105 |

| Alaska | 20 | 40 |

| Arizona | 30 | 60 |

| Arkansas | 35 | 100 |

| California | 40 | 80 |

| Colorado | 35 | 65 |

| Connecticut | 36 | 151 |

| Delaware | 21 | 41 |

| Florida | 40 | 120 |

| Georgia | 56 | 180 |

| Hawaii | 25 | 51 |

| Idaho | 35 | 70 |

| Illinois | 59 | 118 |

| Indiana | 50 | 100 |

| Iowa | 50 | 100 |

| Kansas | 40 | 125 |

| Kentucky | 38 | 100 |

| Louisiana | 39 | 105 |

| Maine | 35 | 151 |

| Maryland | 47 | 141 |

| Massachusetts | 40 | 160 |

| Michigan | 38 | 110 |

| Minnesota | 67 | 134 |

| Mississippi | 52 | 122 |

| Missouri | 34 | 163 |

| Montana | 50 | 100 |

| Nebraska | 49 | Unicameral |

| Nevada | 21 | 42 |

| New Hampshire | 24 | 400 |

| New Jersey | 40 | 80 |

| New Mexico | 42 | 70 |

| New York | 62 | 150 |

| North Carolina | 50 | 120 |

| North Dakota | 47 | 94 |

| Ohio | 33 | 99 |

| Oklahoma | 48 | 101 |

| Oregon | 30 | 60 |

| Pennsylvania | 50 | 203 |

| Rhode Island | 38 | 75 |

| South Carolina | 46 | 124 |

| South Dakota | 35 | 70 |

| Tennessee | 33 | 99 |

| Texas | 31 | 150 |

| Utah | 29 | 100 |

| Vermont | 30 | 98 |

| Virginia | 40 | 100 |

| Washington | 49 | 98 |

| West Virginia | 34 | 100 |

| Wisconsin | 33 | 99 |

| Wyoming | 30 | 60 |

In terms of partisan alignment, as of 2023, the political landscape in state legislatures across the United States reflects a continued predominance of Republican control. Since 2016, Republicans have consistently maintained a significant majority of state legislative seats, consolidating their position as the dominant political force in numerous states. Notably, the 2016 elections marked a pivotal moment for the Republican Party, as they achieved their most substantial legislative victory in over a decade by securing control of both houses in 30 state legislatures (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024).

Conversely, Democratic majorities have persevered in maintaining control over both houses in 10 states, albeit facing formidable opposition from their Republican counterparts. This division underscores the ongoing political polarization and competition between the two major parties, shaping the legislative agenda and policy priorities at the state level. However, the political landscape in the remaining 10 states presents a nuanced picture of partisan control, characterized by a split legislature. In these states, one party asserts dominance in one chamber, while the opposing party wields control in the other chamber. This scenario of divided government reflects the complex dynamics of state politics, where competing interests and ideologies often necessitate compromise and negotiation to advance legislative agendas and enact meaningful policy reforms (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024).

The legislative activity across American states exhibits considerable variation in the number of bills introduced and enacted into law, reflecting diverse political landscapes and priorities. For instance, in 2023, New York saw a substantial volume of legislative activity, with 14,823 bills introduced during the year. Of these, 589 bills successfully navigated the legislative process and were enacted into law, highlighting the state's robust policymaking environment and the breadth of issues addressed by state lawmakers (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2024).

In contrast, Wyoming, in the same year, experienced markedly lower levels of legislative activity. Only 391 bills were introduced into the state legislature, indicating a more focused legislative agenda compared to larger and more populous states such as New York. Despite the lower number of bills introduced, Wyoming demonstrated efficient governance, with 204 bills successfully passing into law. This disparity in legislative output underscores the unique challenges and priorities faced by states with smaller populations and less complex policy landscapes, compared to their larger counterparts.

Legislatures in General-Purpose Local Government

General-purpose local governments, which include county governments, municipal governments, and town and township governments, provide a wide range of services that affect the day-to-day lives of citizens. Services such as police protection, road, street and bridge infrastructure, parks and recreation, and land use (zoning) are typical duties of general-purpose governments in the United States. These governments feature both an executive and legislative function, and the executive function is discussed elsewhere. This section focuses on the legislative role of general-purpose local governments whose legislative bodies are boards of county commissions, city councils, and town boards of aldermen or selectmen.

County Commissions: Counties function primarily as the administrative appendages of a state, and thus they implement many state laws and policies (such as carrying out elections) at the local level. The central legislative body in a county government is commonly a board of “commissioners” or “supervisors.” Typically, a county commission meets in regular session monthly or bimonthly, and its legislative responsibilities encompass the enactment of county ordinances, the development and approval of the county budget, and, in some states, the setting of certain tax rates.

City Councils: Municipal government in America originates from the English parish and borough system. The English parish was involved in both church service and road maintenance, while the English borough engaged in commercial and governmental affairs. These traditional aspects of civic society in England were gradually merged into a single entity and developed into the concept of municipality in the United States. In contrast to a county, which is an administrative appendage of a state, a city is considered a municipal “corporation” that can produce and implement its own local laws and public policy. For example, the City of New York creates its own sales tax, apart from the New York State sales tax created by the state government. The executive branch of city governments is generally organized into one of three basic forms: a mayor-council form, a city commission form, and a council-manager form. These executive structures are discussed in detail elsewhere. However the executive authority of the municipality might be organized, the legislative body provided for in each of these three basic forms is typically called a city council, and that legislative body exercises the power to make public policy.

Traditionally, members of most city councils were elected through at-large election, a practice that often resulted in their becoming somewhat unresponsiveness to some groups in their jurisdiction. In recent decades city councils have tended to emphasize district elections, and as a consequence, city councils have become considerably more diverse in terms of gender, race and ethnicity than they were in the past. Today, city legislative bodies are less white and less male and less business-dominated than they were in the past, and feature many more African Americans, Hispanics, and women.

Town Boards: Today, official town and township governments continue to operate in 20 states in three major regions (see Table 7.5). In terms of legislative process, many of these towns have a tradition of direct democracy through a “town meeting” wherein residents elect town officials, enact ordinances, and adopt a budget. Typically, all available voters are invited to provide input, offer amendments, and vote on township business. These types of local government legislatures are often found in smaller jurisdictions.

Table 7.5 Regions and States with Official Towns and Townships

| Regions | States |

|---|---|

| New England | Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island |

| Mid-Atlantic | New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania |

| Mid-west | Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Kansas, Nebraska and Missouri |

The Adapted City: Research by Frederickson and Johnson has found that while almost all U.S. cities were initially established as either a council-manager or mayor-council form of government, they typically “adapt” to incorporate the best features of both systems. They found that over-time, cities with council-manager systems tend to adopt features of mayor-council systems “…to increase their political responsiveness,” and that cities with mayor-council systems tend to adopt features of council-manager systems “…to improve their management and productivity capabilities.” Frederickson and Johnson argue that these developments have led to a third form of municipal governance they call the “adapted city” (Frederickson and Johnson, 2001). As emphasized in the introductory chapter regarding adaptation to change, this is a characteristic of institutional sustainability — the ability of cities to reform their governmental structures to promote economic and administrative efficiency, and to increase political responsiveness and strengthen civil society.

Legislatures in Single-Purpose Local Government

As their name implies, typical single-purpose local governments only have one principal function. These local government entities usually provide services that general-purpose local governments are either unwilling to perform or are incapable of performing. Special district boards and commissions and school district boards constitute the legislative bodies in single-purpose local governments.

Special District Boards: A special district usually has a population of residents occupying a specific geographic area, features a legal governing authority, maintains a legal identity separate from any other governmental authority, possesses the power to assess a tax for the purpose of supplying certain public services, and exercises a considerable extent of autonomy. Special districts have been created for a variety of purposes; for instance, a watershed district aims at promoting the beneficial use of water and a rural hospital district works to maintain health care services to a sparsely populated area. In many areas of the country a sanitary district strives to improve sewerage services, and a rural fire protection district focuses on providing fire protection through a combination of professional and volunteer firefighters. While the vast majority of the special districts in the U.S. perform a single function, a small proportion of them provide two or more services. Local government units known as county service areas in California, for example, provide police protection, library facilities, and television translator services in some sparsely populated areas of the state.

The category of special district governments includes both independent districts and dependent districts. For independent districts, the board members are generally elected by the public, but in some cases board members are appointed by public officials of the state, counties, municipalities, and town/townships that have joined to form special districts (Marks and Hooghe, 2004). Dependent districts are governed by other existing legislatures such as a city council or a county board. For instance, the County Service Areas noted above are dependent districts that are governed by their county boards of supervisors (Mizany and Manatt, 2002). The Oceanside Small Craft Harbor District in California is a subsidiary organ of the City of Oceanside, and the members of the Oceanside City Council also serve on the District’s board (Bui and Ihrke, 2003). To sum up, special districts are independent if the members of boards are independently elected or appointed for fixed term of office; special districts are dependent if they depend on another local government to govern them (Mizany and Manatt, 2002). However they are governed, in their financial and administrative aspects special districts are all considered fiscally ‘independent’ because they exist as separate legal entities and exercise a high degree of fiscal and administrative independence from the general-purpose governments around them.

School District Boards: As a type of single-purpose local government, a school district serves primarily to operate public primary and secondary schools or to contract for public school services. Its legislative body is typically called a “school board” (Condron and Roscigno, 2003) or a “board of trustees,” (Feuerstein, 2002) and the members of these boards can be either elected or appointed for fixed terms of office (Danzberger and Usdan, 1994). Typically, the school board has five to seven members whose job it is to make policy (e.g., adoption of special programs, approval of grant applications, setting disciplinary rules, going to the public to request passage of school levies, etc.) for the school district. One major issue in policy decisions is the development and enactment of a school district budget.

School districts also consist of both independent and dependent units. Independent school districts are defined as local governments that are fiscally and administratively independent of other government entities, such as townships, municipalities, and counties. They can provide for and promote public education, but they are not allowed to use their revenues on public goods other than education. Dependent school districts, in contrast, are not counted as separate governments because they are dependent on a ‘parent’ government capable of shifting public expenditure among various public goods (Barrow and Rouse, 2004). As of the latest available data from 2021, there were 13,363 public school districts in the United States. This is a decrease from the 15,029 public school systems reported in 2002. The reduction in the number of school districts over the years typically reflects consolidation efforts to streamline resources and administration.

Legislatures – What Can I do?

Find out more about state legislatures by visiting the National Council of State Legislators (NCSL) website at: http://www.ncsl.org/

Visit the International City Managers Association’s (ICMA) website to find out current issues confronting municipalities at http://icma.org/ and then use ICMA’s website to locate your own county or city government websites. Go to your own local government’s website and see when city council or country commissioner public meetings are held and attend one. Former U.S. Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill once said “all politics is local,” so go see for yourself what issues are confronting your own local governments and how they are approaching them (https://www.usa.gov/local-governments).

Legislatures and Sustainability

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) emphasizes the pivotal role of local governments in fostering sustainable development. Local government bodies, which include councils and legislative assemblies, are crucial because they craft laws, regulations, and ordinances directly impacting the local community's social, economic, and environmental aspects. These local bodies are often more attuned to the specific needs and challenges of their communities than more centralized forms of government. This close proximity to citizens allows them to engage effectively with citizens and tailor solutions that promote sustainability and inclusivity. For instance, local governments can implement policies promoting renewable energy use, waste reduction, efficient water management, and equitable economic growth as was presented in Chapter 4.

The involvement of local governments is recognized under the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 11, which aims to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. By empowering local authorities and enhancing their capacities, the UN believes that more effective and ground-up approaches to sustainability can be achieved, reflecting the unique contexts and needs of local populations. This approach aligns with broader governance principles that advocate for decentralization, where local autonomy and decision-making are critical for adapting and integrating sustainable practices effectively into the daily lives of citizens. The effectiveness of local governance in contributing to sustainable development can significantly impact global efforts to achieve the SDGs by 2030.

In Governing Sustainable Cities, Evans et al. present a working framework for what factors contribute to community sustainability (Evans et al., 2013). These scholars suggest that sustainability is in major part a function of two community-based components: institutional capacity and social capacity. Institutional capacity is defined in terms of levels of commitment from government officials, the demonstration of political will, investment in staff training, technological mainstreaming, engagement in knowledge-based networks, and provision of legislative support for maintaining network connections. Similarly, social capacity is defined by the degree of inclusion in collective civic efforts of local citizen volunteers, news media, business establishments, representatives of industry, local colleges and universities, and local non-governmental organizations (Evans et al., 2013). Based on the possible combinations of institutional and social capacities, Evans and his colleagues identify four potential governance outcomes (Evans, et al., 2013):

- Dynamic governing – communities with ‘higher’ levels of social and institutional capacity have ‘high possibility of accomplishing sustainability-promoting policy outcomes.

- Active government – communities with ‘lower’ levels of social capacity, but ‘higher’ levels of institutional capacity, have ‘medium or fairly high’ possibility for accomplishing sustainability-promoting policy outcomes.

- Voluntary governing – communities with ‘higher’ levels of social capacity, but ‘low’ institutional capacity, have ‘low’ possibility for accomplishing sustainability-promoting policy outcomes.

- Passive government – communities with ‘low’ levels of both institutional and social capacity have little possibility of achieving a sustainable future.

These findings are comport with the argument of Costantinos to the effect that the active support of the state and local government legislative bodies is a critical predictor of sustainable states and communities. This support is accomplished by (Costantinos, 2006):

…developing systems whereby public opinion can be made known to members of the legislature, including (the level of) support to develop their constituency, developing the capacity of the legislature to draft and introduce legislation or amendments to existing legislation on specific subjects.

As with local government legislatures, state legislatures can significantly influence sustainability through a combination of legislative actions, fiscal policies, and engagement in public-private partnerships. They serve as pivotal platforms for addressing both statewide and regional environmental challenges, as well as setting precedents that can inspire national policies. Some of the tools states have to promote sustainable policies are as follows:

- Legislative Actions: State legislatures can pass laws that mandate or incentivize practices supporting sustainable development. This can include imposing stricter emissions standards for vehicles and industrial activities to reduce air pollution, enacting water conservation laws to manage and protect water resources effectively and legislating against land-use practices that threaten biodiversity. Legislatures can also create frameworks for environmental accountability, requiring companies to report on their environmental impact and progress towards sustainability goals (Mazmanian and Kraft, 2009).

- Fiscal Policies: Through fiscal measures, state legislatures have the power to promote sustainability by redirecting public and private sector investments towards sustainable projects. This can be achieved by offering tax incentives, subsidies, or grants for renewable energy projects such as wind farms or solar panels installations, and by supporting research and development in sustainable technologies. Furthermore, state budgets can allocate significant funds for the restoration and conservation of natural habitats and for upgrading infrastructure to make it more energy-efficient (Chapman, 2008).

- Public-Private Partnerships: By fostering collaborations between the government, private sector, and non-profit organizations, state legislatures can leverage additional resources and expertise to undertake large-scale sustainability projects. These partnerships can facilitate the development of sustainable urban transit systems, energy-efficient buildings, and large-scale reforestation or land rehabilitation projects. Public-private partnerships can also be crucial in disaster resilience, helping states prepare for and respond to environmental crises with sustainable strategies (Pinz et al, 2021).

- Educational and Community Initiatives: Legislatures can also enact policies that support sustainability education in schools and public awareness campaigns to inform citizens about environmental issues and sustainable practices. By integrating sustainability into the educational curriculum, states ensure that future generations are better prepared to deal with environmental challenges. Community initiatives can also include support for local farming, recycling programs, and community-based conservation projects that empower local populations to contribute actively to sustainability goals (Rowe, 2007).

Overall, the role of state legislatures in promoting sustainability is comprehensive, addressing a wide range of issues through laws, policies, and initiatives that can foster an environmentally responsible and resource-efficient society. Their actions are crucial for ensuring that sustainability is embedded in the economic, social, and environmental fabric of their states.

Current Trends in State Legislatures

In the mid 2020s, U.S. state legislatures are tackling a diverse and dynamic array of policy challenges, with key trends shaped by ongoing social, economic, and technological changes. One prominent trend is the rising focus on public health issues, particularly the mental health crisis, substance misuse, and the integration of technology in health services. States are pushing forward initiatives to combat the opioid crisis and increase the availability of mental health resources, reflecting a broader shift towards enhancing the nation’s public health infrastructure (Politico, 2024).

Additionally, the legislative landscape is seeing significant attention on the regulation of emerging technologies, such as AI. States are drafting laws to manage the impacts of AI on privacy and misinformation, particularly concerning “deepfakes” in elections (Bloomberg Government, 2024). Privacy concerns are also driving legislation across the states, with many implementing or planning to implement more stringent data protection laws, influenced by varying local concerns and the broad push for greater consumer privacy protection (Bloomberg Government, 2024).

Education reform continues to be a hot-button issue, with states like Florida and Texas at the forefront of expanding school choice programs and refining how educational funds are utilized, amidst debates over the appropriate use of taxpayer money (Politico, 2024). On housing, states are exploring reforms to streamline building procedures and reduce bureaucratic barriers, which could significantly impact housing affordability and availability (Hamilton, et al., 2023). Immigration and civil rights are also key areas of legislative activity. Numerous states are considering laws that would expand or restrict rights for immigrants and LGBTQ communities, indicating a contentious and varied approach to civil liberties across the nation (American Civil Liberties Union, 2024; Avilez, 2024).

Additional areas of state legislative activity trends include the following:

- Healthcare Expansion and Mental Health: Many states are addressing healthcare accessibility, with initiatives to expand Medicaid and increase mental health services funding. For example, Georgia and other states are exploring ways to extend healthcare to lower-income families in a fiscally responsible manner. Simultaneously, significant investments are being made to bolster mental health services, as seen in North Carolina and Montana, which are making some of the largest investments in mental health care in their histories (Politico, 2024; Route-Fifty, 2023).

- Drug Policy and Overdose Crisis: Addressing the drug overdose crisis remains a top priority, with states like Washington proposing multi-million dollar plans to boost community health hubs and improve naloxone distribution. There's also a growing legislative interest in psychedelics, with states like Oregon leading the way in regulated therapeutic programs, and others like Illinois and California considering similar measures (Politico, 2024).

- Education and School Choice: Education reform, particularly regarding school choice and voucher programs, is a hot topic. Florida and Texas are notable examples where lawmakers are seeking to refine and expand voucher programs that allow public education funds to be used for private schooling. This includes tightening regulations on what the funds can be used for if provided to private schools (Politico, 2024).

- Technology and Privacy: States are increasingly focusing on technology's role in society, with several legislating against the risks posed by AI-generated deepfakes in elections and setting new standards for consumer privacy. Efforts to manage the impact of social media on young people are also evident, with states like Utah implementing age verification and enhanced parental controls for social media use by minors (Bloomberg Government, 2024).

- Electric Vehicles and Infrastructure: With federal funding from the Biden Administration’s Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, states are ramping up the build-out of electric vehicle charging infrastructure. This includes not only enhancing the charging network but also ensuring its accessibility in underserved areas (Politico, 2024; Route-Fifty, 2023).

Another disturbing trend in state legislatures is increasing incivility (Lovrich et al., 2021). Incivility in U.S. state legislatures has been a growing concern in recent years, reflecting a broader trend of political polarization. This behavior encompasses a range of disruptive and contentious actions among lawmakers, often undermining the legislative process and longstanding rules of decorum. One of the most visible aspects of this trend is the increasing partisan hostility and lack of capacity to find common ground across the political aisle. Lawmakers frequently engage in hostile exchanges, utilizing personal attacks and derogatory language. This environment of heightened antagonism often leads to a refusal to collaborate across party lines on issues requiring agreement to address pressing issues such as homelessness and school truancy, significantly impeding legislative progress and deepening the divide within legislative bodies.

The consequences of such incivility are far-reaching. Disruptions in proceedings, such as lawmakers shouting down speakers, interrupting sessions, and staging walkouts, have become more frequent and visibly contentious. These actions not only stall the legislative process but also prevent the passage of crucial legislation, affecting governance and public trust. Moreover, the rise of social media as a platform for public discourse has introduced a new arena for incivility. Legislators often use these platforms to sharply criticize their opponents in ways that can be disrespectful or inflammatory, exacerbating tensions both within legislative chambers and with the public. Additionally, although rare, there have been instances where disputes among legislators have escalated into physical altercations, starkly illustrating the breakdown of traditional norms of conduct and respectful disagreement. Such episodes of incivility lead to legislative gridlock, where little substantive legislation is passed, and polarize issues to the extent that achieving bipartisan cooperation becomes increasingly challenging. This dynamic underscores the pressing need for reforms aimed at restoring civility and functionality in state legislatures.

Some examples of state legislative incivility include the following:

- Oregon – Walkout to Block Legislation: In recent years, Republican senators in Oregon have repeatedly staged walkouts to block legislation, particularly to prevent the passage of climate change legislation. This tactic, while legal, has been criticized as highly disruptive and an abandonment of democratic responsibilities. The walkouts have prevented the legislature from reaching a quorum, effectively halting all legislative activity.

- Texas – Physical Scuffle Over Immigration Law: In 2017, a physical altercation broke out on the floor of the Texas House of Representatives. The confrontation occurred after a Republican lawmaker called for Immigration and Customs Enforcement action on protesters who were opposing a new state law targeting sanctuary cities. The situation escalated when he was confronted by Democratic lawmakers, leading to shoving and threats being exchanged.

- Pennsylvania – Verbal Abuse During a Session: In 2019, a session in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives turned uncivil when a Democratic member started shouting insults during a debate, referring to the sitting speaker as a “tyrant” among other things. This incident was part of a larger pattern of heated exchanges that session, reflecting deep-seated tensions between the political parties in the state.

- Idaho – Disruption Over COVID-19 Measures: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Idaho legislature saw significant disruptions, including from its own members who opposed pandemic-related restrictions. In one instance, a lawmaker made headlines by participating in a protest that involved burning masks on the Capitol steps, and another brought a large group of unmasked citizens into a gallery that was supposed to be limited to lawmakers.

- Michigan – Threats of Violence Over Election Certification: Following the 2020 presidential election, legislators in Michigan faced threats of violence and intense pressure as they debated the certification of election results. Some lawmakers reported receiving threatening messages and calls, which were part of a broader wave of hostility related to election outcomes across several states.

A central driving force of the increased incivility is the rise of "Trumpism" in American politics, which encompasses the political style, rhetoric, and policies of former President Donald Trump, has undeniably affected the climate of civility within state legislatures (Lebow, 2019). The brand of Trumpism is characterized by heightened political polarization, often manifesting in more combative and uncompromising positions being taken among lawmakers. This shift in political culture has emboldened legislators to engage in confrontational behavior and has weakened the longstanding tradition of bipartisan cooperation. Such a political environment leads to increased incivility, as fact-based public policy discussions are overshadowed by personal attacks, partisan positioning, and ultimate legislative deadlock. The U.S. House of Representatives exemplifies legislative partisan gridlock; that same brand of political stalemate is being replicated in many state legislatures.

Moreover, Trumpism has encouraged some state legislators to challenge established norms and conventions of political engagement which once were strongly held by both Democratic and Republican lawmakers. This erosion of traditional decorum, often justified as a means to an end for political strategy, has led to an increase in use of inflammatory language, disruptions of proceedings, and at times, outright threats against political adversaries. The impact extends to legislative debates on hot-button issues, such as election integrity, immigration, and pandemic responses — topics that are central to Trump's rhetoric and that resonate strongly with his base of supporters. This influence has rendered such issues incendiary within legislative chambers, with debates marked by intense incivility that mirrors the emotional and ideological fervor of Trumpism. The resulting dynamic is a legislative landscape wherein civility is in decline – both across partisan lines and within the legislative caucuses, making the path toward restoring respectful dialogue and bipartisan efforts more challenging.

Current Local Government Legislative Trends

Current trends in U.S. local governments involve addressing both immediate and long-term challenges, with a strong emphasis on fiscal management, social issues, technology, and infrastructural development. After the pandemic stimulus, local governments are bracing for the time when these funds wane, meaning that fiscal prudence is crucial to maintain stability and credit quality. They are proactively managing changes, especially in the context of economic headwinds like high interest rates and shifts in commercial and residential real estate markets. The response to the evolving needs of commercial real estate and its implications for local tax bases is particularly significant (Ridley, 2024).

The challenges of providing senior-friendly housing and infrastructure are becoming increasingly urgent as the population ages. In New York City, the number of seniors is growing, with the senior population more racially diverse than a decade ago and many living in poverty with limited English proficiency. Affordable housing for seniors is in short supply, with long waiting lists for programs like the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Section 202 Supportive Housing for the Elderly program. The number of working seniors has grown, and a significant portion of senior-headed households rely heavily on Social Security benefits for more than half of their income (Lander, 2017).

Nationally, the issue is compounded by the lack of homes ready to accommodate the needs of older adults. Most homes are not equipped to deal with the difficulties faced by adults who may have mobility issues or other disabilities. Only about 10% of homes in the U.S. have aging-accessible features like step-free entryways, first-floor bedrooms and bathrooms, and handrails or built-in shower seats in bathrooms. This scarcity is even more pronounced in certain regions, like the Mid-Atlantic, where only 6% of homes are considered aging-ready (Vespa, 2020).

The suburbs, where a large majority of seniors and their families live, face particular challenges. They tend to be car-dependent, and with increasing numbers of seniors no longer driving, the lack of public transportation options can lead to social isolation. There is a pressing need for the development of more walkable suburban communities with accessible retail amenities and services. Some towns and developers are recognizing this and creating mixed-use, walkable communities that are attractive to seniors, integrating senior housing into the fabric of these communities, which helps to spread the costs of services commonly associated with senior living (Fang, 2013).

Local governments are intensively working to bridge the digital divide, as equitable access to broadband internet is essential for participation in education, healthcare, employment, and even maintaining social connections. The digital divide not only affects rural areas but also urban communities. For example, approximately 18% of residents in New York City lack broadband access. This issue spans across demographic lines and has been exacerbated during the pandemic, highlighting the necessity of reliable internet access for daily activities.

To address these challenges, the federal government has made significant commitments, such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which provides $65 billion for broadband expansion. This includes the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD) allocating $42.45 billion for broadband deployment to underserved communities, and efforts to promote digital equity and broadband affordability through a $1.3 billion investment in the Digital Equity Act. California has initiated a considerable investment of $6 billion to enhance internet access across the state. This plan includes the development of a state-owned open access middle mile network and last mile projects to connect unserved households and businesses, aiming to reach underserved and rural communities (DePreta, 2023).

Cybersecurity remains a high priority, with state and local governments aiming to protect their infrastructures from cyber threats. This focus is due to the significant role states play in various critical sectors and the recognition of cyber resilience as essential to public safety and service continuity. At the same time, the IT landscape in local government is expected to grow, presenting an opportunity to innovate and improve services for residents. Investments in workforce development are also being emphasized to address skill shortages and to bolster economic growth and job creation (DePreta, 2023).

Moreover, governments are taking advantage of technological advancements, like AI, to improve public service delivery and operations, with a significant drive toward enhancing customer experiences. There's also a noticeable trend towards fostering innovation ecosystems and cross-sector collaboration to tackle complex challenges and transform mission effectiveness (Deloitte, 2024).

Conclusion