Chapter 8. Working with Institutional Review Boards

Introduction

The thought of having to submit a proposal to IRB for approval has been enough to turn away many students (and some practitioners) from engaging in qualitative research. IRB approval is generally required for any studies involving “human subjects.” It may seem easier to work with numbers rather than people. Although I share common frustrations with delays and bureaucratic hassles associated with IRBs, on the whole, seeking IRB approval for your study should not keep you from doing the kind of research you want to do or answering the questions that truly matter to you. This chapter will walk you through what you need to know to have a successful relationship with your institutional review board.

What are IRBs?

Any researcher whose research includes “human subjects” is required by federal guidelines to have their research protocol reviewed in advance by their institution’s ethical review panel.[1] In the US, these panels are known as institutional review boards, or IRBs. The federal policy on human subjects research is often referred to simply as the Common Rule. First codified as such in 1974, the Common Rule was substantially revised in 2017, with those revisions being implemented in 2019. In the grand scheme of things, these rule changes are very new, so the first thing you must realize is that much of what has been written about IRBs and the Common Rule has since changed. As a new student to qualitative research, you will be operating under the new updated Common Rule, and this may differ from what your teacher or past researchers understood. That said, the changes were not quite as substantial as some had hoped (more on this below). More commonly, the shifting guidelines put a lot of burden on local IRBs to modify their reviewing practices. As this often included structural changes in personnel and software, resulting delays occurred in 2019–2021, just as the global pandemic hit. Your institution may still be working to adapt. These adaptations are really the first major change since the inception of the IRB system in the 1970s.

The Common Rule and the establishment of IRBs occurred on the heels of several well-publicized ethical breaches in research design and study of the mid-twentieth century. In the 1930s, there was the infamous Tuskegee experiment, in which African American men, roughly half of whom had syphilis, had treatment withheld. Horrendous and inhumane medical “experiments” by Nazi doctors during the 1940s came to light during the 1947 Nuremberg trials, leading to calls for the regulation and oversight of medical experiments and the eventual “Nuremberg Code.”

The Nuremberg Code (1947)

Permissible Medical Experiments

The great weight of the evidence before us to effect that certain types of medical experiments on human beings, when kept within reasonably well-defined bounds, conform to the ethics of the medical profession generally. The protagonists of the practice of human experimentation justify their views on the basis that such experiments yield results for the good of society that are unprocurable by other methods or means of study. All agree, however, that certain basic principles must be observed in order to satisfy moral, ethical and legal concepts:

- The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential. This means that the person involved should have legal capacity to give consent; should be so situated as to be able to exercise free power of choice, without the intervention of any element of force, fraud, deceit, duress, overreaching, or other ulterior form of constraint or coercion; and should have sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the elements of the subject matter involved as to enable him to make an understanding and enlightened decision. This latter element requires that before the acceptance of an affirmative decision by the experimental subject there should be made known to him the nature, duration, and purpose of the experiment; the method and means by which it is to be conducted; all inconveniences and hazards reasonably to be expected; and the effects upon his health or person which may possibly come from his participation in the experiment.The duty and responsibility for ascertaining the quality of the consent rests upon each individual who initiates, directs, or engages in the experiment. It is a personal duty and responsibility which may not be delegated to another with impunity.

- The experiment should be such as to yield fruitful results for the good of society, unprocurable by other methods or means of study, and not random and unnecessary in nature.

- The experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation and a knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study that the anticipated results justify the performance of the experiment.

- The experiment should be so conducted as to avoid all unnecessary physical and mental suffering and injury.

- No experiment should be conducted where there is an a priori reason to believe that death or disabling injury will occur; except, perhaps, in those experiments where the experimental physicians also serve as subjects.

- The degree of risk to be taken should never exceed that determined by the humanitarian importance of the problem to be solved by the experiment.

- Proper preparations should be made and adequate facilities provided to protect the experimental subject against even remote possibilities of injury, disability or death.

- The experiment should be conducted only by scientifically qualified persons. The highest degree of skill and care should be required through all stages of the experiment of those who conduct or engage in the experiment.

- During the course of the experiment the human subject should be at liberty to bring the experiment to an end if he has reached the physical or mental state where continuation of the experiment seems to him to be impossible.

- During the course of the experiment the scientist in charge must be prepared to terminate the experiment at any stage, if he has probable cause to believe, in the exercise of the good faith, superior skill and careful judgment required of him, that a continuation of the experiment is likely to result in injury, disability, or death to the experimental subject.

Despite this code, the Tuskegee experiment continued in the US (until 1972), as did several other unethical studies: the Willowbrook study of hepatitis transmission in a hospital for mentally impaired children, the Fernald School trials using radioactive minerals in impaired children, and the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital case in which chronically ill patients were injected with cancer cells.

The National Research Act was passed in 1974, creating the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. This commission authored the Belmont Report, enunciating three ethical principles that form the basis of acceptable human subjects research. These principles are the following:

Respect for persons. Treat individuals as autonomous human beings, capable of making their own decisions and choices; do not use people as a means to an end. Respect for person requires (1) obtaining and documenting informed consent; (2) respect the privacy interests of research subjects; and (3) considering additional protection when conducting research on individuals with limited autonomy (e.g., children, prisoners and others under custodial supervision).

Beneficence. Minimize the risks of harm and maximize the potential benefits. Beneficence requires: (1) using procedures that present the least risk to subjects consistent with answering the research question(s); (2) gathering data from procedures or activities that are already being performed for non-research reasons; (3) ensuring that risks to subjects should be reasonable in relation to both the potential benefits to the subjects and the importance of the knowledge expected to result from the study; (4) maintaining promises of confidentiality; and (5) monitoring the data to ensure the safety of subjects.

Justice. Treat people fairly and design research so that its burden and benefits are shared equitably. Justice requires: (1) selecting subjects equitably (not excluding a group out of bias or mere convenience) and (2) avoiding exploitation of vulnerable populations or populations of convenience.

These principles should look familiar to you if you read chapter 7, as they are similar to the general ethical principles of qualitative research. You might notice, however, that the context of the Belmont Report and some of its language on principles are geared toward the kinds of biomedical research that had raised concerns (e.g., What does “monitoring the data to ensure the safety of subjects” mean in the context of interview-based research?). Indeed, the Common Rule that followed from the Belmont Report was really created with the image of human subjects in medical experiments in mind and so imperfectly aligned itself with codes of ethics that made sense for those who talked to people (rather than injecting them with a potential vaccine). This would become a big issue in the following decades and was the primary reason the Common Rule was revised in 2017.

The IRB review system was designed following the Belmont Report to provide an independent, objective review of research involving human subjects. Any institution that received federal funding was subject to the Common Rule. Rather than create a corps of federal agents reviewing research protocols, the Common Rule required each and every research institution (all colleges, hospitals, research foundations) to create its own review panel, known as its IRB. In accordance with federal regulations, an IRB has the authority to approve, require modifications in, or disapprove research. According to the regulations, the IRB must be composed of diverse members,[2] including at least one person from the local community outside of the institution itself. In practice, most IRBs also include at least one attorney. For university IRBs, the majority of its members are drawn from different disciplines (e.g., there might be one biology faculty member and one sociologist). These are not full-time positions, which explains some of the delays and long processing times students confront (and complain about). Some applications will require “full-board review,” while others can be addressed by IRB representatives.

The Common Rule Since 2019

IRB jurisdiction is triggered whenever there is research involving human subjects. Part of the changes implemented in the Common Rule had to do with defining both “human subjects” and “research.” You may wonder why this was necessary, but consider the following: Is asking your grandmother questions about her childhood for a classroom project “research”? Does an IRB have to review your research design before you talk to her? What about the journalist who observes the Taliban taking over Kabul and then writes about this for the New York Times? What if she includes quotes from Afghanis? Or this: You collect information from blogs about cooking for a thesis on cultural transmission. Do you need IRB approval here? Or this: You code and analyze diaries of people who lived through the US Civil War for a dissertation in US history. Before the Common Rule clarifications, some IRBs were in fact claiming that all were human subjects research (see “Advanced: IRB Imperialism?” for more). This caused a great deal of frustration and confusion among researchers, journalists, librarians, historians, and students.

According to recent clarifications, a human subject is “a living individual about whom an investigator conducting research obtains (1) information or biospecimens through intervention or interaction with the individual, and uses, studies, or analyzes the information or biospecimens; or (2) uses, studies, analyzes, or generates identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens” (45 CFR 46). I have added the italics to emphasize the aspect of this definition most applicable to qualitative research (we do not take biospecimens). Note that the individual must be living, so historical analyses of diaries or oral histories fall outside IRB jurisdiction. There are still ethics involved in doing this kind of research, but your IRB will not be weighing in on those. Note, too, that the information must be gained through some form of interaction. This would seem to suggest that preexisting data sets such as already collected oral histories or blogs, even of living persons, are also outside the IRB’s jurisdiction (although there are privacy concerns; see [2] of the definition).

Not everything involving human subjects is covered by IRBs. The interaction must be part of “research.” (This requirement excludes most journalism and classroom projects.) Research is designed as “a systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge” (emphases added). If you are writing a research paper for a class and you are not expecting to publish that paper beyond the classroom, it does not count as “research” under this definition. Further, if you are collecting data from human subjects for the sake of the data itself and not to make any analyses based on that data, it is not research (think of the US Census or data gathered by public health officials). My own institution’s IRB (the Oregon State University Institutional Review Board) clarifies that “the intent or purpose of the systematic investigation is dissemination of findings (publication or presentation) outside of OSU” and is “intended to have an impact (theoretical or practical) on others within one’s discipline.”[3] Activities that are specifically not deemed to be research include “scholarly and journalistic activities” such as oral histories, journalism, biographies, literary criticism, legal research, and most historical scholarship. Government functions with separately mandated protections (e.g., US Census) are not research.

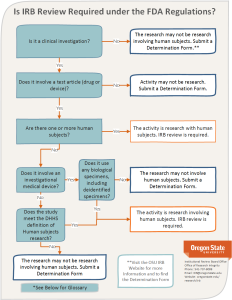

Figure 8.1 displays the decision tree used at Oregon State University for determining IRB jurisdiction.

Applying the Belmont Principles to Human Subject Research

Now that we know what “human subjects research” is in IRB-land, we need to understand how the three Belmont principles are applied to research that is subject to review.

As part of the Respect for Persons principle, IRBs are looking to ensure that human subjects have consented to be part of the study. People cannot consent to something they do not understand, so IRBs look to ensure that potential participants have been duly informed about both the study itself and their rights regarding the study (e.g., the right to opt out at any time, something denied the men in the Tuskegee experiment). IRBs will carefully scrutinize consent forms and recruitment material. Most IRBs recognize informed consent as a process, not a single document. Information must be presented that will enable potential participants to voluntarily decide whether to enroll in the study and then also to stay in the study during its duration. Anything that could pressure participation (such as including one’s employee or student) will raise red flags. The procedures used in obtaining informed consent, including recruitment flyers, should be designed to educate potential study participants in terms that they can understand. IRBs will probably stop you from recruiting participants with a promise of money in bold letters. Your IRB may also ask you to include a translation of the document if you are recruiting persons whose primary language is not English.

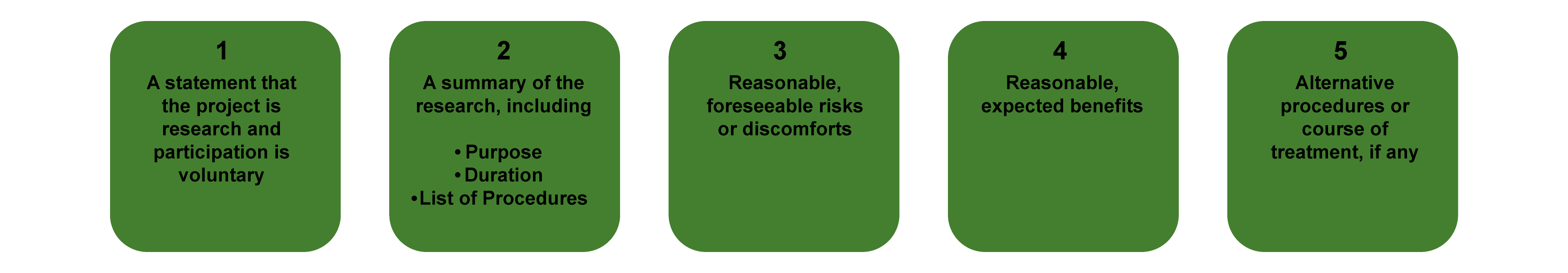

There are some standard attributes to include on any consent form (figure 8.2). Your IRB office probably has a template it makes available to researchers. Download this, and adapt it to your study.

In general, deception is frowned upon, as it undercuts informed consent. As mentioned in the previous chapter, however, there are a few recognized exceptions. Deception may be permitted when all of the following obtains:

- The study must not involve more than minimal risk to the subjects.

- The use of deceptive methods must be justified by the study’s significant prospective scientific, educational, or applied value.

- The protocol must clearly address why deception or incomplete disclosure is necessary to ensure that the research is scientifically valid and feasible and that an alternative, nondeceptive methodology could not be used.

- Subjects should not be deceived about any aspect of the study that would affect their willingness to participate.

In addition, an immediate debriefing, when possible, is often required.

IRBs will also look to see that you have presented the study so that the risks of harm are minimized and the potential benefits (e.g., knowledge production, increased understanding) are maximized (Beneficence principle). They will want to know that you are conducting the study with as minimal intrusion as possible and that you have thought about the importance of the research and balanced this against the inconvenience or harm that could accrue to the people you are studying. Further, IRBs spend a lot of care ensuring that you are taking all available precautions against breaches of confidentiality and anonymity. At a minimum, they will want you to include descriptions of how you are safeguarding the data you collect, where you are warehousing it (e.g., a password-protected computer file), and how long you will store it after the completion of the study.

Finally, IRBs will review your application for adherence to the Justice principle. They will scrutinize your protocol to ensure that you have selected your subjects equitably (not excluding a group out of bias or mere convenience) and that you have avoided exploiting vulnerable populations or populations of convenience.

There are three levels of IRB review: full, expedited, and exempt. Full-board reviews are invoked when a preliminary review (sometimes by a single IRB representative) indicates that the research involves greater than minimal risk or is of minimal risk research but does not meet one or more of the expedited review categories. Full review is used whenever vulnerable populations are included in the protocol. Vulnerable populations have historically encompassed children, prisoners, and pregnant persons. There are separate guidelines listing when expedited review is possible (see your own IRB website for its list). Exempt review is a specific subset of research involving human subjects that does not require continuing IRB oversight. Studies that are deemed full or expedited require continuing review. Changes in the protocol can move a study from one category of review to another. If all of this sounds confusing, welcome to bureaucracy! There are good reasons for IRB to set its own guidelines for how the categorizations work, as each institution is a bit different in the kinds of research that are likely to be reviewed. You will have to work with your IRB for more clarity in this area.

Working with your IRB

Every institution has a unique IRB. It is helpful to find your IRB’s website and review the process described there. Although all adhere to the Common Rule, the actual process of review may differ. Some IRBs use software programs to help route applications between expedited, exempt, and full-board reviews. Smaller institutions are likely to have more personal review processes where you may end up talking to an actual person who manages the entire process. Given the substantial changes enacted in the Common Rule in 2017, it is likely that your IRB’s website has been recently updated and includes a wealth of helpful material.

Know that the process takes a lot of time and that the actual amount may depend on staffing at your institution. A fully functioning IRB may take two to three weeks to review your protocol. Another may take six to nine months. It is helpful to know in advance the time frame for your application process. Ask your IRB or colleagues at your institution who have recently submitted a study for review. Know what triggers “full-board review” (e.g., inclusion of “vulnerable” populations). Note, too, that many IRBs require some determination of whether a study is “exempt” from IRB review. In other words, even if you are pretty sure that what you are doing is not “human subjects research” (see above), you may still have to go through some form of review process.

Have all of your documents in shape for submitting your application, as any errors or missing documents will delay the review process. Although each IRB’s process is different, you can generally expect to include at least the following documents for a qualitative project:

- Protocol (research design). This should include a full description of your sample and site selection, how participants will be recruited, how consent will be obtained, and how documents (e.g., transcripts, consent forms) will be safeguarded. The reviewers will also need to know about your research question and the importance of the study so they can balance the benefits and costs of the study.

- Consent form. Your IRB will probably have its own template for this (see the website). If not, there are numerous models available online, and I have included a basic one here as well. You will want to make sure you include a decent description of the study targeted to your audience, that you include contact information for you (the principal investigator, or PI) and the IRB, and that you include the signature and date lines as well as separate initial lines if you are asking for consent to be recorded (audio and/or video).

- Recruitment material. If you are using a poster/flyer or email to distribute, you will need to attach this to your protocol. The IRB will be looking for clarity and honesty in your recruitment materials.

Once you have submitted your materials, keep in touch with your IRB. If your IRB uses a software system, you may be able to monitor the process online and will be able to know if it gets held up somewhere. Otherwise, contact the IRB if things seem to be taking longer than one would expect (knowing what you know about how your IRB works)—it may be that there is a problem with your materials that you need to correct.

I cannot stress strongly enough that it pays to establish a good working relationship with your IRB office. Be polite in all correspondence with IRB officers, and when you have been assigned an IRB tracking number, use this number in the subject line of any correspondence. Reach out if you have questions. They really are there to help you.

Advanced Reading: IRB Imperialism?

Throughout its history, two major critiques have been leveled at IRBs by qualitative researchers. The first is that, designed to prevent unethical biomedical experiments and often composed of members who do those kinds of research, IRBs are ill-equipped to review most qualitative research. Second, and relatedly, “mission creep” of IRBs and federal regulations more broadly has occurred. Thus, IRBs were never very well suited to reviewing the kinds of work qualitative researchers do (interviewing and observing humans), and they have been increasingly intrusive over the decades. At the very least, “there is a culture clash in the bureaucratic gatekeeping demands of the IRB and the emergent ‘figure it out as you go along’ character” of qualitative research (Lareau 2021:39). But some critics have gone so far as to charge IRBs with silencing important research, or at least putting so many hurdles in the way that researchers opt out of more challenging (and potentially insightful) research designs. Recall that most IRBs have a lawyer or two on board. Lawyers are famously wary of litigation and tend to encourage boards to withhold permission to study those with power or who might otherwise cause conflict. Graduate students in particular are advised or compelled to seek less controversial subjects or to avoid human subjects entirely as being too much of a hassle. After all, there is no IRB that will stand in the way of quantitative analyses of already collected data sets. Pressure to change the Common Rule was relentless throughout the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, eventually resulting in the 2017 revision, which, to many, was “too little too late.” Although the jurisdiction of IRBs has been somewhat scaled back (see above), the larger critiques remain, and there is some reason to fear mission creep will reassert itself in the future.

Two books published during the fight to change the Common Rule speak eloquently to these issues. Schrag’s (2010) historical analysis of how qualitative research became included in the jurisdiction of the Common Rule in the first place and with what consequences is a fascinating read. Each field of research, Schrag argues, has, by necessity, its own ethical rules and guidelines. What works to protect human subjects against biomedical experimentation is not the same at all as what will protect a human subject against being exploited and used by an unethical ethnographer who leaves the field precipitously. How did the biomedical researchers manage to impose their own field’s rules so completely on another field? This “ethical imperialism” resulted in an ethics regime that is “contrary to the norms of freedom and scholarship that lie at the heart of American universities” (8). For the sake of simplicity, regulators “forced social science research into an ill-fitting biomedical model” (9). The regime was created largely in response to biomedical ethical violations (e.g., Tuskegee), with very little attention paid to social sciences and humanities. Questions over the meaning of “human subjects” and “research” were never properly answered. In speaking of the National Commission, “it was as if a national commission on the lime industry had completed its work without deciding whether it was regulating citrus fruit or calcium oxide” (76). Further, “IRB review of the social sciences and the humanities was founded on ignorance, haste, and disrespect. The more people understand the current system as a product of this history, the more they will see it as capable of change” (192).

Van den Hoonaard (2011), writing contemporaneously of research ethics boards (REBs) in Canada, whose establishment paralleled IRBs in the US, demonstrates how their reach has impaired and deformed qualitative research during this period. Researchers have tailored their approaches in response to technical demands imposed by REBs, leading social science disciplines to resemble one another more closely and to lose the richness of their research: “Many social scientists get lost in the moral tundra because the signage speaks to biomedical research, as opposed to social research” (4). By observing the work of REBs (a qualitative research in and of itself!), Van den Hoonaard uncovers the social relations and power tied up in this ethics regime. Rather than seeing research as a right, review boards act as if research is a privilege, retaining the power to themselves to grant or deny permission. Researchers then employ particular strategies of avoidance or partial or full compliance as they seek approval from ethics committees. Both researchers and individual members of the ethics review system recognize that something is not working here, but no one is able to change course. The current ethics regime offers an inappropriate model for social science research. It can sometimes appear to strangle legitimate research, curtail academic freedom, and throw up so much red tape that the actual pursuit of doing qualitative research ethically gets lost in the bureaucratic “normalization” of ethics (55).

The changes to the Common Rule have addressed some of the concerns of Schrag and Van den Hoonaard. Furthermore, the issues they speak of (mission creep, silencing and diverting studies away from the powerful) occurred variously depending on location. Some IRBs have been better managers of the delicate balance between protecting human subjects and advancing important research than others. I hope that however your IRB operates, you do understand that the ethics of your research should not be confined to or equated with IRB review. There are many other ethical issues raised by qualitative research that by and large go unexamined by IRBs and REBs (see chapter 7). It is helpful to understand the role and place of IRBs and how they particularly protect you and your university from incurring legal liability. Try not to get too frustrated with the bureaucracy. And most of all, remember that your role as an ethical researcher is ongoing, and securing IRB approval for a study is just one of many duties and responsibilities you bear.

Research Consent Form

Study Title:

Principle Investigator:

Study team:

Version*Date:

We are inviting you to take part in a research study.

Purpose: This study is about…..

We are asking you if you want to be part of this study because……

You should not be in this if……

Voluntary: You do not have to be in this study if you do not want to. You can also decide to be in the study now and change your mind later.

Activities: The study activities…

Time: Your participation in this study will take approximately…

Risk: The possible risks or discomforts associated with being in this study include…

Benefit: This study is not designed to benefit you directly. Your participation will advance knowledge in this area. [discuss any other possible benefits]

Confidentiality: We cannot assure that the information you provide will be entirely safe from breaches of confidentiality, but we will take the following steps to ensure this…

Payment: You [will OR will not] be paid for being in this research study. [describe]

Study contacts: We would like you to ask us questions if there is anything about the study that you do not understand. You can call us at …. or email us at ….

You can also contact the [IRB office] with any concerns you have about your rights or welfare as a study participant. The office can be reached at … or by email at….

Signatures:

Your signature indicates that this study has been explained to you, that your questions have been answered, and that you agree to take part in the study. You will receive a copy of this form.

Participant Name:____________________________

Participant Signature:_________________________

Date Signed:________________________________

Do you agree to be recorded (video/audio): YES/NO Initial:

Name of Person Obtaining Consent:___________________________

Signature of Person Obtaining Consent:________________________

Date Signed:_______________________

For Further Readings on IRB

Boser. Susan 2007. “Power, Ethics and the IRB: Dissonance over Human Participant Review of Participatory Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 13(8): 1060-1074. Addresses various challenges IRBs pose for participatory research.

Cheek, Julianne 2007. “Qualitative Inquiry, Ethics, and the Politics of Evidence: Working within these Spaces rather than Being Worked over by Them.” Qualitative Inquiry 13(8): 1051-1069. Argues for the necessity of creativity when dealing with the audit culture and other aspects of knowledge regimes associated with IRBs.

Howe, Kenneth R., and Katharine Cutts Dougherty. 1993. “Ethics, Institutional Review Boards, and the Changing Face of Educational Research.” Educational Researcher 22(9): 16-21. Gives an historical overview of special exemptions of IRB review for educational research and discusses which kinds of educational research should properly be exempt.

Lincoln, Y.S. and Tierney, W.G., 2004. “Qualitative Research and Institutional Review Boards.” Qualitative Inquiry 10(2): 219-234. Reports several actual case studies where IRBs impeded qualitative research and provides strategies for addressing IRB concerns in the proposal to avoid these kinds of problems.

Nelson, Carey. 2004. “The Brave New World of Research Surveillance.” Qualitative Inquiry 10(2):207-218. Examines the problem of IRB jurisdiction over humanities and social science research. Argues this poses a potential threat to academic freedom.

- The remainder of this chapter will focus on the set of guidelines in place in the United States. Other nations have their own sets of guidelines for ethical review. For example, Canada employs REBs (research ethics boards) instead of IRBs (institutional review boards). ↵

- The actual regulations require that, as part of being qualified as an IRB, the IRB must have a “diversity of members, including consideration of race, gender, cultural backgrounds and sensitivity to such issues as community attitudes” (21 CFR 56.107(a)). ↵

- See the website: https://research.oregonstate.edu/irb/does-your-study-require-irb-review. ↵

An administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated. The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research involving human participants. The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects. The IRB has the authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

Research, according to US federal guidelines, that involves “a living individual about whom an investigator (whether professional or student) conducting research: (1) Obtains information or biospecimens through intervention or interaction with the individual, and uses, studies, or analyzes the information or biospecimens; or (2) Obtains, uses, studies, analyzes, or generates identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens.”

The section of US federal regulations that establishes the core procedures for human research subject protections, which include informed consent and review by an institutional review board (IRB). The Common Rule was substantially revised in 2017. See chapter 8 for more details.

The report of the US National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, first published in 1974. It identified the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of research involving human subjects and developed guidelines to ensure that such research is conducted in accordance with those principles.

An ethical and legal requirement for research involving human participants; the process whereby a participant is informed about all aspects of the research so they can make an informed decision to participate. The concept of informed consent is embedded in the principles of the Belmont Report. Obtaining consent involves informing the subject about his or her rights, the purpose of the study, procedures to be undertaken, potential risks and benefits of participation, expected duration of study, and the extent of confidentiality of personal identification and demographic data.

One of the three principles identified in the Belmont Report: the risks of harm should be minimized and the potential benefits (e.g., knowledge production, increased understanding) should be maximized. In other words, the benefits of the study should outweigh any harm (including discomfort to the participants). Just because one is able to conduct a study does not mean one should or that the study is worth pursuing

One of the key principles found in the Belmont Report and a foundational ethical requirement for all research involving human subjects. “Respect for persons incorporates at least two ethical convictions: first, that individuals should be treated as autonomous agents, and second, that persons with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. The principle of respect for persons thus divides into two separate moral requirements: the requirement to acknowledge autonomy and the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy”- Belmont Report.

One of the three principles identified in the Belmont Report: the human subjects involved in the research should be equitably chosen (i.e., not excluding a group out of bias or mere convenience), and the researcher should avoid exploiting vulnerable populations or populations of convenience.

A specific subset of research involving human subjects that is deemed more than “minimal risk” or involves one of the definitions of vulnerable population and thus requires review by a formally convened committee (board) meeting. All full-board studies must adhere to the requirements for informed consent or its waiver or alteration. Full-board studies must undergo annual review.

A specific subset of research involving human subjects that is no more than “minimal risk” and fits in one of the federally designated expedited review categories. Expedited reviews do not require a convened committee meeting. All expedited studies must adhere to the requirements for informed consent or its waiver or alteration. Expedited studies may or may not be required to undergo annual review.

A specific subset of research involving human subjects that does not require ongoing IRB oversight. Research can qualify for an exemption if it is no more than minimal risk and all of the research procedures fit within one or more of the exemption categories in the federal IRB regulations.

A detailed description of any proposed research that involves human subjects for review by IRB. The protocol serves as the recipe for the conduct of the research activity. It includes the scientific rationale to justify the conduct of the study, the information necessary to conduct the study, the plan for managing and analyzing the data, and a discussion of the research ethical issues relevant to the research. Protocols for qualitative research often include interview guides, all documents related to recruitment, informed consent forms, very clear guidelines on the safekeeping of materials collected, and plans for de-identifying transcripts or other data that include personal identifying information.

The term used in Canada for entities reviewing human subjects research, parallel to IRB in the US.