Chapter 19. Advanced Codes and Coding

Introduction: Forest and Trees

Chapter 17 introduced you to content analysis, a particular way of analyzing historical artifacts, media, and other such “content” for its communicative aspects. Chapter 18 introduced you to the more general process of data analysis for qualitative research, how you would go about beginning to organize, simplify, and code interview transcripts and fieldnotes. This chapter takes you a bit deeper into the specifics of codes and how to use them, particularly the later stages of coding, in which our codes are refined, simplified, combined, and organized for the purpose of identifying what it all means, theoretically. These later rounds of coding are essential to getting the most out of the data we’ve collected. By the end of the chapter, you should understand how “findings” are actually found.

I am going to use a particular analogy throughout this chapter, that of the relationship between the forest and trees. You know the saying “You can’t see the forest for the trees”? Think about what this actually means. One is so focused on individual trees that one neglects to notice the overall system of which the trees are a part. This is something beginning researchers do all the time, and the laborious process of coding can make this tendency worse. You focus on the details of your codes but forget that they are merely the first step in the analysis process, that after you have tagged your trees, you need to step back and look at the big picture that is the entire forest. Keep this metaphor in mind. We will come back to it a few times.

Let’s imagine you have interviewed fifty college students about their experiences during the pandemic, both as students and as workers. Each of these interviews has been transcribed and runs to about 35 pages, double-spaced. That is 1,750 pages of data you will need to code before you can properly begin to make sense of it all. Taking a sample of the interviews for a first round of coding (see chapter 17), you are likely to first note things that are common to the interviews. A general feeling of fear, anxiety, or frustration may jump out at you. There is something about the human brain that is primed to look for “the one common story” at the outset. Often, we are wrong about this. The process of coding and recoding and memoing will often show us that our initial takes on “what the data say” are seriously misleading for a couple of reasons: first, because voices or stories that counter the predominant theme are often ignored in the first round, and, second, because what startles us or surprises us can drive away the more mundane findings that actually are at the heart of what the data are saying. If we have experienced the pandemic with little anxiety, seeing anxiety in the interviews will surprise us and make us overstate its importance in general. If we expect to find something and we see something very different, we tend to overnotice that difference. This is basic psychology, I am sure.

This is where coding comes in to help you verify, amplify, complicate, or delimit your initial first impressions. Coding is a rigorous process because it helps us move away from preconceptions and other judgment errors and pin down what is actually present in the data. It helps you identify the trees, which is actually important before we can properly see the forest. We start with “It’s a forest” (not really that helpful), then move to “These are specific trees, with particular roots and branches,” and finally move back to a better understanding of the forest (“It’s a boreal forest that works like this…”). Coding is the rigorous connecting process between the first (often wrong or incomplete) impression and the final interpretation, the “results” of the study (figure 19.1). If you remember that this is the point of coding, you will be less likely to get lost in the woods. Coding is not about tagging every possible root and branch of every tree to create some kind of master compendium of forest particulars. Coding is about learning how to identify what is important about that forest overall.[1] When you are new to the forest, you won’t know which root or branch is of importance, but as you walk through it again and again, you will learn to appreciate its rhythms and know what to pick up as important and what to discard as irrelevant.

There is no single correct way to go about coding your data. When I first began teaching qualitative research methods, I resolutely refused to “teach” coding, as I thought it was a little like trying to teach people to write fiction. It’s very personal and best developed through practice. But I have come to see the value of providing some guidelines—maps through the forest, if you will. I have drawn heavily here from Johnny Saldaña’s extensive and beautiful “coding manual,” but the particular suggestions here are what have worked best for me. We are going to walk through the forest many times, first in an open exploratory way and then in a more focused way once we have found our stride. Finally, we will sit down with all of our maps and materials and see what it is we can discover about the world by looking at our data.

First Walks in the Woods: Open Coding

Saldaña (2014) provides dozens of types of codes and coding processes, but we are going to confine our discussion two five. These are the five kinds of codes that I think work best for beginning researchers in your first walks through the woods. Used together, they have the potential to get at the heart of what is important in social science research. They are descriptive, in vivo, process, values, and emotions. Select a sample of your data in the first round of coding. If you tried to tag everything in these initial rounds, you will never get out of the woods. Your sample should be broad enough to capture essential aspects of your data corpus but small enough to allow you free rein to pick up as many branches as you think interesting. Set aside a significant amount of time for this. And then double or triple that time allotment. You’ll need it.

Descriptive codes are codes used to tag specific activities, places, and things that seem to be important in particular passages. They are identifying tags (“This is a branch from an elm tree”; “This is an acorn”). Be careful here because you can really end up trying to identify everything—every word, every line, every passage. Don’t do that! It’s helpful to remind yourself what your research is about—what is your research question or focus? Some twigs can stay on the forest floor. Saldaña’s (2014) use of the term is narrower. Descriptive codes are meant to summarize the basic topic of a passage in a single word or short phrase, what is also called “topic coding” or “index coding.” These descriptive codes will allow you to easily search for and return to passages about a particular topic or feature of the forest; this will allow you to make better comparisons in later rounds of analysis. The actual word or phrase you come up with will be rather personal to you and dependent on the focus of your research. Here is an exemplary passage from a fictitious interview with a working-class college student: “I had no idea what scholarships were available! No one in my family had ever gone to college before, so there was no one I could ask. And my high school counselor was always too busy. What a joke! Plus, I was a little embarrassed, to be honest. So, yeah, I owe a lot of money. It’s really not that fair.”

What descriptive codes can be developed here? How would you define the topic or topics of this passage? On the one hand, the subject appears to be scholarships or how this student paid for college. “How Pay” might be a good descriptive code for the entire passage. But there are a lot of other interesting things going on here too. If your focus is on how peer groups work or social networks, you might focus on those aspects of the passage. Perhaps “No Assistance” could work as a descriptive code in this first round of coding. Descriptive codes are pretty straightforward, so they are easy for beginning researchers to use, but “they may not enable more complex and theoretical analyses as the study progresses, particularly with interview transcript data” (137).

In vivo codes are codes that use the actual words people have used to tag an important point or message. In the above passage, “no one I could ask” might be such a code. These indigenous terms or phrases are particularly useful when seeking to “honor or prioritize” the voice of the participants (Saldaña 2014:138). They don’t require you to impose your own sense on a passage. They are also rather enjoyable to generate, as they encourage you to step into the shoes of those you have interviewed or observed. The terms or phrases should jump out at you as something salient to your research question or focus (or simply jump out at you in surprising ways that you hadn’t expected, given your research question).

Process codes are codes that label conceptual actions. This is another way to describe the data, but rather than focus on the topic, we organize it around key actions and activities. For example, we could tag the passage above with “asking for help.” By convention, process codes are gerunds, those strange verb forms that end in -ing and operate a bit like nouns. Process codes are particularly helpful for studies that focus on change and development over time, as the use of tagged gerunds can really highlight stages, if such exist. Grounded theorists often employ process codes for this reason. I find it useful, as it reminds me to focus not only on what participants say and how they say it but on the activities that they are engaged in.

Values codes are codes that reflect the attitudes, beliefs, or values held by a participant. Values codes capture things such as principles, moral codes and situational norms (“values”), the way we think about ourselves and others (“attitudes”), and all of our personal knowledge, experience, opinions, assumptions, biases, prejudices, morals, and other interpretive perceptions of the world (“beliefs”). They are extremely powerful tags and absolutely essential for phenomenological researchers. We might attach the values code “unfair” to the passage above or even note the “What a joke!” passage as disbelief or disgust.

Values codes are a particular subset of affective coding, where codes are developed to “investigate subjective qualities of human experience (e.g., emotions, values, conflicts, judgments) by directly acknowledging and naming those experiences” (Saldaña 2014:159). The fifth suggested code is also another form of affective coding, emotions codes, labels of feelings shared by the participants. “Embarrassment” is an obvious emotion code in the above passage. In the kinds of research I mostly do, phenomenological and interview based, often about sensitive subjects around discrimination, power, and marginalization, coding emotions is incredibly helpful and productive: “Emotion coding is appropriate for virtually all qualitative studies, but particularly for those that explore intrapersonal or interpersonal participant experiences and actions, especially in matters of identity, social relationships, reasoning, decision-making, judgment, and risk-taking” (160).

A Final Purposeful Hike through the Forest: Closed Coding

After initial rounds of coding (several walks through the woods), you should begin to see important themes emerge from your data and have a general idea of what is important enough to look at more closely. Between first-cycle coding and your last hike through the forest, you will have created a list of codes or even a codebook that records these emergent categories and themes (see chapter 18). It is quite possible your research question(s) or focus has shifted based on what you have seen in the first rounds of coding.[2] If you need more data collection based on these shifts, collect more data. Once you feel comfortable that you have reached saturation and know what it is you are looking at and for, you are ready for one final purposeful hike through your forest to tag (code) all your data using a pared-down set of codes.

Building Meaning, Identifying Patterns, Comparing Trees, and Seeing Forests

The final cycle of coding is also the time to generate analyses of your data. As with so much qualitative research, this is not a linear process (finish stage A and move to stage B followed by stage C). To some extent, analysis is happening all the time, even when you are in the field. Journaling, reflecting, and writing analytical memos are important in all stages of coding. But it is in the final stages of coding that you truly start to put everything together—that’s when you start understanding the nature of the forest you have been walking through. That, after all, is the point. What do all these codes of various people’s actions (fieldnotes) or people’s words (interviews) tell you about the larger phenomenon of interest? This will require mapping your codes across your data set, comparing and contrasting themes and patterns often relative to demographic factors, and overall trying to “see” the forest instead of the trees.

Different researchers employ various tools and methods to do this. Some draw pictures or concept maps, seeking to understand the connections between the themes that have emerged. Others spend time counting code frequencies or drawing elaborate outlines of codes and reworking these in search of general patterns and structure. Some even use in vivo codes to generate found poems that might provide insight into the deeper meanings and connections of the data. Mapping word clouds is a similar process. As a sociologist who is interested in issues of identity, my go-to method is to look for interactions between the codes, noting demographic elements of comparison. For example, in the very first study I conducted (Hurst 2010a), I used emotion codes. Specifically, I found numerous examples of sadness, anger, shame, embarrassment, pride, resentment, and fear. With the exception of pride, these are not very positive emotions. I could have stopped there, with the finding of overwhelming instances of negative emotions in the stories told by working-class college students. But I played around with these categories, clustering them by incidence and frequency and then comparing these across demographic categories (age, race, gender). I found no race or gender differences and only a hint of a difference between traditional-age college students and older students. What I did find, however, was that the emotions sorted themselves out in clusters relative to other codes. Embarrassment, shame, resentment, and fear were often found together in the same interview, along with a pattern of using “they” to refer to working-class people like the interviewees’ families. Conversely, anger, sadness, and pride were often found together, along with a pattern of using “we” to refer to working-class people. This led me to develop a theory about how working-class students manage their class identities in college, with some desirous of becoming middle class (“Renegades”) and others wanting very strongly to remain identified as working class (“Loyalists”; Hurst 2010a).

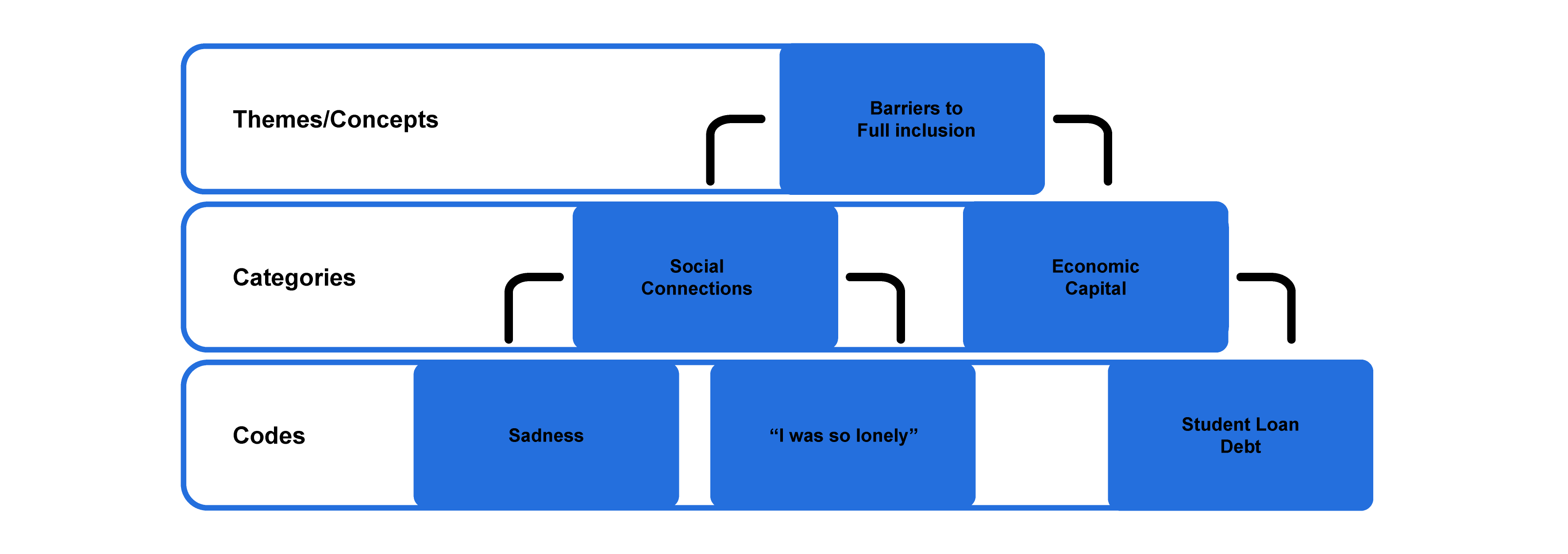

Saldaña (2014) summarizes many of these techniques. He draws a distinction between "code mapping" and “code landscaping.” Code mapping is a systematic and rigorous reordering of all codes into an increasingly simplified hierarchical organization. One can move from fifty or so specific stand-alone codes of various types (e.g., sadness, “I was so alone,” socializing, financial aid) and attempt to impose some meaningful order on them by clustering like phenomena with like phenomena. Perhaps sadness (an emotion code), “I was so alone” (an in vivo code), and socializing (an action code) are understood as belonging together, perhaps under a category of SOCIAL CONNECTIONS or, depending on what has emerged from your data, EXCLUSION. Code mapping is an iterative process, meaning that you can do a second or a third take of simplification and reordering. In the end, you might be left with one or two big conceptual themes or patterns.

Code landscaping “integrates textual and visual methods to see both the forest and trees” (Saldaña 2014:285). Using computer-assisted word cloud mapping (WordItOut.com, wordclouds.com, wordle.net) is one way of doing this, or at least a way to jump-start the process. Word clouds quickly allow you to see what stands out in the interview or fieldnotes and can suggest relationships of importance between codes. Manually, one can also diagram the codes in terms of relationship, stressing the processual elements (what leads to what: “I felt so alone” >> sadness).

Another helpful suggestion is to chart the incidence of codes across your data set. This is particularly helpful with interview data. What (simplified) codes emerge in each interview transcript? Is there a pattern here? The two categories of Loyalist and Renegade would not have emerged had I not made these kinds of code comparisons by person interviewed. You might create a master document or spreadsheet that places each interview subject on its own row, with a brief description of that person’s story (what emerges as the focus of the interview or who they are in terms of social location, character, etc.) in a separate column and then a third column listing the key codes found in the interview. This is a good way to “see” the forest in a snapshot.

Whatever method or technique is employed, the general direction is to move from simple tags (codes) to categories to themes/concepts (figure 19.2). Eventually, those identified themes/concepts will help you build a new theory or at a minimum produce relevant theoretically informed findings, as in the second example at the end of this chapter.

Grounded Theory has its own vocabulary when it comes to coding and data analysis, so if you are trying to do a “proper” Grounded Theory study, you might want to read up on this in more detail (Charmaz 2014; Strauss 1987; Strauss and Corbin 2015). A quick summary of the approach follows. First-cycle coding employs the following kinds of codes: in vivo, process, and initial. Second-cycle coding employs focused, axial, and theoretical codes. The names of these second-cycle codes are meant to evoke the Grounded Theory approach itself: in the second cycle, the grounded theorists focus the study on axes of importance to generate theories. Focused coding pulls out the most frequent or significant codes from the first round. Axial coding reassembles data around a category, or axis. These categories or axes are meant to be concept generating: “Categories should not be so abstract as to lose their sensitizing aspect, but yet must be abstract enough to make [the emerging] theory a general guide” (Glaser and Strauss 1967:242). Theoretical codes “function like umbrellas that cover and account for all other codes and categories” (Saldaña 2014:314). Key words or key phrases (e.g., “Exclusion” or “Always Crying”) capture the emergent theory in the theoretical code.

Describing and Explaining the Forest: Findings and Theories

It is only now, after the laborious process of coding is complete, that you can actually move on to generate and present findings about your data. Many beginning researchers attempt to skip the middle work and get straight to writing, only to find that what they say about the data is pretty thin. The quality of qualitative research comes from the entire analytical process: open and closed coding, writing analytical memos, identifying patterns, making comparisons, and searching for order in the voluminous transcripts and fieldnotes.

But let’s say that you have followed all the steps so far. You have done multiple rounds of coding—refining, simplifying, and ordering your codes. You’ve looked for patterns. You think you have seen some master concepts emerge, and you have a good idea of what the important themes and stories are in your data. How do you begin to explain and describe those themes and stories and theories to an audience? Chapter 20 will go into further detail on how to present your work (e.g., formats, length, audience, etc.), but before we get to that, we need to talk about the stage after coding but before writing. You will want to be clear in your mind that you have the story right, that you have not missed anything of importance, and that you have searched for disconfirming evidence and not found it (if you have, you have to go back to the data and start again on a new track).

Begin with your research question(s), either as originally asked or as reformulated. What is your answer to these questions? How have your underlying goals (see chapter 4) been addressed or achieved by these answers? In other words, what is the outcome of your study? Is it about describing a culture, raising awareness of a problem, finding solutions, or delineating strategies employed by participants? Perhaps you have taken a critical approach, and your outcome is all about “giving voice” to those whose voices are often unheard. In that case, your findings will be participant driven, and your challenge will be to present passages (direct quotes) that exemplify the most salient themes found in your data. On the other hand, if you have engaged in an ethnographic study, your findings may be thick, theoretically informed descriptions of the culture under study. Your challenge there will be writing evocatively. Or to take a final example, perhaps you undertook a mixed methods study to find the best way to improve a program or policy. Your findings should be such that suggest particular recommendations. Note that in none of these cases are you presenting your codes as your findings! The coding process merely helps you find what is important to say about the case based on your research questions and underlying aims and goals.

The gold star of qualitative research presentation is the formulation of theory. Even for those not following the Grounded Theory tradition, finding something to say that goes beyond the particulars of your case is an important part of doing social science research. Remember, social science is generally not idiographic. A “theory” need not be earth shattering, as in the case of Freud’s theory of Ego, Id, and Superego. A theory is simply an explanation of something general.[3] It is a story we tell about how the world works. Theories are provisional. They can never be proven (although they can be disproven). My description of Loyalists and Renegades is a theory about how college students from the working class manage the problem of class identity when their class backgrounds no longer match their class destinations. While qualitative research is not statistically generalizable, it is and should be theoretically generalizable in this way. Loyalists and Renegades are strategies that I believe occur generally among those who are experiencing upward social mobility; they are not confined solely to the twenty-one students I interviewed in 2005 in a college in the Pacific Northwest.

What is the story your research results are telling about the world? That is the ultimate question to ask yourself as you conclude your data analysis and begin to think about writing up your results.

Further Readings

Note: Please see chapter 18 for further reading on coding generally.

Charmaz, Kathy 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Although this is a general textbook on conducting all stages of Grounded Theory research, a significant portion is directed at the coding process.

Strauss, Anselm. 1987. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. An essential reading on coding Grounded Theory for advanced students, written by one of the originators of the Grounded Theory approach. Not an easy read.

Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 2015. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A good basic textbook for those exploring Grounded Theory. Accessible to undergraduates and graduate students

- A small aside here on social science in general and sociology in particular: It is often believed that sociologists are concerned about “people” and what people do and believe. Actually, people are our trees. We are really interested in the forest, or society. We try to understand society by listening to and observing the people who compose it. Behavioral science, in contrast, does take the individual as the object of study. ↵

- It might be helpful to read the first example of writings about qualitative data analysis in the "Further Readings" section. ↵

- Saldaña (2014) lists five essential characteristics of a social science theory: “(1) expresses a patterned relationship between two or more concepts; (2) predicts and controls action through if-then logic; (3) accounts for parameters of or variation in the empirical observations; (4) explains how and/or why something happens by stating its cause(s); and (5) provides insights and guidance for improving social life” (349). ↵

A form of first-cycle coding in which codes are developed to “investigate subjective qualities of human experience (e.g., emotions, values, conflicts, judgments) by directly acknowledging and naming those experiences” (Saldaña 2021:159). See also emotions coding and values coding.

A technique of second-cycle coding in which codes developed in the first rounds of coding are restructured into an increasingly simplified hierarchical organization, thereby allowing the general patterns and underlying structure of the field data to emerge more clearly.

A technique of second-cycle coding that “integrates textual and visual methods to see both the forest and trees" (Saldaña 2021:285).

A first-cycle coding process in which terms or phrases used by the participants become the code applied to a particular passage. It is also known as “verbatim coding,” “indigenous coding,” “natural coding,” “emic coding,” and “inductive coding,” depending on the tradition of inquiry of the researcher. It is common in Grounded Theory approaches and has even given its name to one of the primary CAQDAS programs (“NVivo”).

A later stage coding process used in Grounded Theory that pulls out the most frequent or significant codes from initial coding.

A later stage coding process used in Grounded Theory in which data is reassembled around a category, or axis.

A later stage-coding process used in Grounded Theory in which key words or key phrases capture the emergent theory.