Chapter 2: Court Procedures

2.1 How Much is A Leg Worth? What do Civil Trial Courts Do, and Why Should We Care?

What do Civil Trial Courts Do, and Why Should We Care?

Tao Dumas

Abstract

This essay explores the function and role of state civil jury trials and the political and policy debates surrounding them. The most recent Republican Party Platform calls for additional tort reforms to protect doctors from frivolous lawsuits and reduce consumer costs. Yet while the political conflict over the civil justice system continues, these courts remain severely understudied, largely due to a lack of data availability. Consequently, much of the debate relies on limited empirical evidence. Despite the constrained scholarly attention, especially in political science, state civil trial courts of general jurisdiction are the final arbiters of the law in most civil cases. In order to begin to understand what these critically important courts do, I review legal academic and political science literature related to state court decision-making and case processing. I then use an original data collection of civil jury verdicts in four states (Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee) to examine variation in docket composition, winners and losers, and institutional design across the states, with specific attention to tort reforms. For example, Alabama has enacted 29 different tort reforms, second only to Texas in total reforms. Meanwhile, Indiana utilizes institutional review boards, a type of reform where groups of medical professionals make a pre-trial determination about the merits of medical malpractice cases, with the proposed intent of reducing meritless malpractice trials. I then discuss possible relationships between institutional variation and jury verdicts.

Although an infrequent topic of discussion, civil trial courts are important and powerful institutions that rely on judges and juries to settle disputes and prescribe (typically) monetary retribution for injuries. By allowing injured parties to access the justice system and seek compensation for harms, the civil courts serve four primary purposes: 1) dispute resolution; 2) creating predictability in societal actors’ behavior; 3) deterring misconduct and modifying conduct; and 4) allocating resources (Shapiro 1981). In civil cases, injured litigants, often individuals or groups with limited resources, bring suits against defendants who may possess “deep pockets,” asking juries to convert damages to dollars by determining both the winner and the appropriate compensation. Civil trials often pit “have-not” plaintiffs against the “haves” (Galanter 1974). These courts constitute one of the few institutions where ordinary people and groups with grievances can directly access the government to solve their disagreements, challenge wealthy and powerful businesses and organizations, and obtain a remedy for their injuries through monetary awards. Damage awards also perform the important function of punishing individuals, businesses, and organizations that engage in reckless or negligent behavior that harms others and encouraging them to cease said behavior. Moreover, the use of juries to solve most civil disputes allows members of the local community to determine winners and losers and appropriate compensation for injuries. Although civil trial courts clearly perform a central institutional and societal role, the merits of allowing lay jurors to solve disputes has and continues to be the subject of much deliberation among academics, reformers, and policymakers.

These persistent normative and political tensions regarding the role of civil juries in American society give rise to two empirical questions: First, are there observable differences in the way that civil juries resolve disputes and render damage awards from one community to another? Secondly, if we observe differences across communities, what factors might explain those differences? Civil trial courts operate in a variety of social and political contexts and under varying laws and constraints. This is especially true in the state courts where each state is largely allowed to decide how to organize and structure its courts and develop its own institutional rules. According to Brace and Hall (1993), “Institutional arrangements, which consists of internal and external rules as well as organizational structures, determine the aggregation of individual preferences within any given institutional body (916).” As such, varying institutional court structures and contexts might lead to disparate outcomes for similar cases. In order to better to understand what these critically important courts do, I begin by discussing the debates surrounding the civil justice system and the history of the tort reform movement. Next, I review legal academic and political science literatures related to the actors in civil justice system and state court institutions. I then use an original data collection of civil jury verdicts in four states (Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee) to examine variation in docket composition, winners and losers, and institutional design across the states, with specific attention to tort reforms and judicial selection methods. I then discuss possible relationships between institutional variation and jury verdicts.

Debating the Civil Justice System

During the ratification debates the Federalists and Anti-Federalists contested the desirability of the constitutional protection of civil juries. The Anti-Federalists, preferring strong local government, argued that civil juries empowered communities to settle disputes themselves based on local standards. “Juries are constantly and frequently drawn from the body of the people, and freemen of the country; and by holding the jury’s right to return a general verdict in all cases sacred, we secure to the people at large, their rightful control in the judicial department (Federal Farmer XV, Storing 1981, 320).” On the other hand, the Federalists maintained that civil juries were outmoded and produced inconsistent applications of the law from one jurisdiction to another, jeopardizing the rule of law. Hamilton argued that, “The capricious operation of so dissimilar a method of trial in the same cases, under the same government, is of itself sufficient to indispose every well regulated judgment towards it…The best judges of the matter [civil juries] will be the least anxious for a constitutional establishment of the trial by jury in civil cases…”(Federalist 83, Goldman 2008, 416).

Although the Framers ultimately included the Seventh Amendment’s guarantee of the right to a jury trial in all disputes involving claims greater than $20, the disagreement between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists closely mirrors the current debate about tort law, a type of civil litigation where an injured party or parties seeks compensation by suing another party or parties for failing to act in a reasonably responsible way and causing an injury. Today’s tort reform advocates frequently espouse the need to protect doctors and businesses from meritless lawsuits and limit the amount of money civil juries may award injured parties in order to bring down consumer costs and insurance premiums, especially for medical malpractice litigation. Groups seeking to limit the discretion available to jurors argue that trial verdicts do not represent rational, consistent analyses of the conflicts at bar, and variability in outcomes negatively affects businesses and individuals involved in litigation. Opponents of civil juries maintain that when individuals and groups bring frivolous lawsuits and/or when juries award unwarranted or excessively large damage awards, civil courts drive up the cost of doing business and either force doctors and companies out of business or increase consumer costs.

Conversely, those who trust the constitutional mandate of a trial by jury assert that jurors are capable of equitable resolutions. First, proponents of civil juries argue that juries are more sensitive to community values and are therefore more capable of deciding liability and determining damages regarding complex or conflicting social issues than judges. Additionally, juries serve to localize courts in the federal structure and allow citizens to govern themselves (Chapman 2007). Similarly, Haddon argues that juries provide the opportunity for diverse groups to contribute to legal decision-making and “provide the local knowledge and experience and community connection” that judges and experts lack (1994, 61). Furthermore, juries might better represent the community, since jury verdicts reflect group decisions, rather than the decisions of a single judge (Jonakait 2006). Second, Litan (1993) states that supporters of civil juries maintain that jurors can restrain governmental abuses of power. Finally, Litan states that advocates of civil juries rely on De Tocqueville’s belief that civil juries educate citizens about democracy. Marder (2003) maintains that juries fulfill an important political role in addition to educating citizens in the democratic process, because juries also make difficult political decisions regarding complex civil disputes.

In political science, two common definitions of politics include “competition over scares resources” and “who gets what, when, why, and how” (Lasswell 1950). Referring to the politics of tort reform, Burke (2002) states, “[The] battle is highly partisan, with most Republicans taking the anti-litigation side and most Democrats lined up with the plaintiffs. These are struggles over distributional justice—who gets what— (27).” These arguments over civil litigation clearly reflect a disagreement over how resources should be distributed and who should make the allocation decisions, thus representing a classic political debate. Moreover, limitations on individuals’ and groups’ rights to sue for damages directly affect their ability to seek and obtain justice and have their grievances redressed by a court.

History of the Tort Reform Movement

Although efforts to restrict tort law prominently emerged in the 1980s, the call for reform began in the 1970s and continues. Congress has taken up several tort reform proposals, all unsuccessful to date. Congress enacted the first federal tort reform legislation in 1996; however, President Clinton vetoed both bills (see Allen 2006 for a more detailed discussion of the history of tort reform). President George W. Bush, in his 2004 State of The Union Address,[1] called for enacting caps on medical malpractice damage awards, once again bringing national attention to the issue. Despite congressional failure to enact reforms during the Bush administration, calls for national legislation continued, particularly during the Obama administration’s efforts to enact the Affordable Care Act. In fact, in the 2011 State of The Union Address, President Obama suggested medical malpractice reform as a potential way to bring down health care costs, in spite of Democrats’ traditional opposition to tort reform. In reference to bringing down health care expenses, President Obama said, “Still, I’m willing to look at other ideas to bring down costs, including one that Republicans suggested last year — medical malpractice reform– to rein in frivolous lawsuits.”[2] The 2016 Republican Party Platform again called for tort reform to bring down healthcare costs.[3] Most recently, in June 2017, the House of Representatives passed a bill that would limit the amount injured plaintiffs could receive for noneconomic damages to $250,000 and limit the amount attorneys could collect in medical malpractice cases, but the bill was unsuccessful in the Senate. Even though tort reform advocates failed to achieve federal legislation, tort reform garnered considerable success in the states, with every state enacting at least one reform.

The Civil Justice System, Purposes, and Processes

A civil case involves four sets of key actors, litigants, lawyers, judges, and jurors who act within specific institutional contexts and arrangements. To better understand the civil justice system, I will begin by discussing the trial process as it relates to each actor and review related scholarly literature. I then discuss how overarching institutional features might affect the behavior of the actors. Although this research focuses primarily on the factors that influence civil litigation outcomes, it should be noted that trials represent only the final stage of the litigation process (Miller and Sarat 1980). “It is well known however, that only a small fraction of disputes come to trial and an even smaller fraction is appealed” (Priest and Klein 1984). Baum (1998) estimates that 62% of all cases settle without a trial. According to Baum trials settle at very high rates because trials present serious drawbacks for litigants: Litigation is expensive; the parties to the dispute lose control of the resolution; judges and juries may deliver unfavorable outcomes; and litigation increases the conflict between the parties. In fact, Engel and Steele (1979) describe the civil litigation process as a pyramid. “The life of a legal case can be conceived in terms of five stages: (1) the primary event, (2) the response decision, (3) pre-judicial processing, (4) judicial processing, and (5) implementation and consequences” (Engel and Steel 1979, 300). Each stage of the pyramid contains fewer claims as disputes are resolved through various means, with trials representing the least common civil disputes.

Litigants

Every civil dispute begins with a plaintiff’s alleged accident or injury and the decision on the part of the injured to hire an attorney to represent his/her interests. Civil courts of general jurisdiction process both contractual disputes (cases in which one party argues that the other failed to uphold the terms of a prior legally binding agreement) and torts. Plaintiffs’ injuries can result from either intentional or unintentional, negligent behavior. Although the civil justice system technically allows anyone with a legitimate injury to bring a suit, Galanter’s now famous party capability theory exposes how the basic architecture of the legal system serves to systematically advantage the “haves” over the “have-nots” (Galanter 1974). Scholarship in this vein generally relies on litigants’ status as individuals, businesses, and organizations to serve as proxies for haves and have-nots, and in general, studies examining litigant success before U.S. courts find support for the notion that well-resources parties such as businesses garner more favorable outcomes when compared to individuals (Farole 1999; Songer and Sheehan 1992; Songer, Sheehan, and Haire 2000). In particular, the government possesses considerable resources and uses them to achieve success rates far greater than other litigant class (Farole 1999; Kritzer 2003). Litigant status appears to consistently impact the likelihood of achieving a favorable ruling before a court (Kinsey and Stalans 1999). Furthermore, disparities in success rates grow as the inequality in resources between the parties increases (Songer, Sheehan, and Haire 1999). Since civil trails routinely pit “have-not” plaintiffs against better-resourced defendants, Galanter’s theory predicts that plaintiffs might encounter considerable disadvantages in achieving compensation for their injuries in court.

Lawyers

Once the injured party contacts a personal injury attorney, the attorney must decide whether to take the case. Scholars maintain that plaintiffs’ lawyers are important gatekeepers to civil justice system who largely determine whether a plaintiff’s grievance becomes litigation (Daniels and Martin 2015; Kritzer 1997-98, 1999; Yeazell 2018). According to Priest and Klein (1984), parties and their attorneys make strategic calculations when deciding to bring a case to trial based on the expected costs and the probability of favorable and unfavorable outcomes based on the decision standards in place, the uncertainty about the relative merits and potential success of any case, and the stakes for the parties involved.[4] Due to attorney strategy, trial courts adjudicate only the most contentious and unpredictable cases.

Most plaintiff attorneys in civil cases utilize contingency fees, a compensation system where lawyers defer payment until the case is successfully settled and receive a portion of their client’s winnings, to attract clients. The inherent risk and uncertainty in contingency fee practice (Daniels and Martin 2000, 2002; Kritzer 2004) encourages attorneys to seek speedy case processing (Kritzer 1990) and makes settlement and negotiation central features of the civil practice (Kritzer 1991, 2004, 2015). Whether and how much insurance coverage the defendant possesses largely dictates whether an attorney will take the plaintiff’s case (Yeazell 2018). Although insurance does not determine whether a defendant is or is not liable, insurance policies provide the assets from which damages can be collected, and the policy limits determine whether an attorney can profit from the claim. If a lawyer will need to invest more money in a case than the defendant’s policy limits, the case is not profitable and an injured plaintiff is unlikely to obtain legal representation, regardless of the merit of the plaintiff’s claim. Yeazell argues that, “In a world where litigants pay their own lawyers and in which money damages predominate as a remedy, few will sue an insolvent, or even a poor, defendant” (2018, 16).

Scholars note that the contingency fee system allows more “have-nots” to participate in the legal system (Karsten 1997; Kritzer and Krishnan 1999), since those with strong cases can obtain high quality representation (Yeazell 2018). Yet plaintiff attorneys routinely face better-resourced defense attorneys who often serve as corporate counsel and typically receive pay regardless of the outcome, which could disadvantage plaintiffs in the negotiation and settlement process. In fact, Heinz et al. (1998) observe that 90% personal injury lawyers who represent plaintiffs practice in small firms or solo practice. However, Dumas, Haynie, and Daboval (2015) uncover evidence that local plaintiffs’ lawyers, despite practicing in smaller firms with fewer resources, appear to use their familiarity with the local legal community to offset resource imbalances when pursuing cases against larger out-of-town firms. Overall, the literature suggests that lawyers working on a contingency fee basis must strategically screen cases for profitability, and plaintiffs with strong cases can obtain legal representation, although that lawyer might be outmatched by the defense in terms of resources.

Once an attorney accepts a case, and the attorney files an official a document called a complaint with the court, the case becomes a trial. A complaint states the plaintiff’s alleged injury, the defendant’s role in causing that harm, and the desired remedy.

Judges & Jurors

While most civil cases end in settlement (Eisenberg and Lanvers 2009; Galanter 2004; Yeazell 2018), those cases that survive the pretrial process without settling then go on to trial. The trial judge plays a key role in shaping the trial and exercises considerable discretion at the trial and pretrial phases of litigation. Judges determine jurisdictional questions, limits on discovery, the trial date, pretrial publicity issues, change of venue requests, and motions to dismiss or for summary judgment, give jury instructions, render judgment notwithstanding the verdict decisions, and make other important decisions that affect a trial’s resolution. In Democracy in America, Alexis De Tocqueville ascribes a substantial role to judges and their ability to influence juries in civil trials. De Tocqueville states, “It is the judge who sums up the various arguments which have wearied their [jurors‘] memory, and who guides them the devious course of the proceedings; he paints their attention to the exact question of fact that they are called upon to decide and tells them how to answer the question of law. His influence over them [jurors] is unlimited” (Tocqueville 1948, 286). If Tocqueville is correct, the judge presiding over a case likely possess a considerable role in influencing the outcome, which also suggests a role for institutional rules that condition judges’ behavior.

The trial concludes after both parties present their arguments, and the judge then instructs the jury on the points of law relevant for the particular case. Judges typically give two types of jury instructions, pattern and general jury instruction.[5] General instructions involve the burden of proof, inferences, demeanor of jurors, unanimous verdicts, and admission of expert testimony. Pattern instructions are specific to the individual case. For example, depending on the case type, judges will provide definitions of negligence, wantonness, or other torts. The judge also informs the jurors of the charge on damages. In other words, the judge tells the jury the type of damages the plaintiff seeks (pain and suffering, future damages, punitive damages, or special damages). For civil cases, the jury must evaluate the severity of the plaintiff’s alleged injury. Then, the jury must decide if the defendant’s actions or inactions caused the plaintiff’s injury.

If the jury deems the defendant liable, the jury must then determine the appropriate compensation. In Determining Damages (Greene and Bornstein 2003) outline three broad types of damages that juries consider. Compensatory damages are damages intended to repay the injured party and return him or her to pre-injury levels of function or replace the loss caused by the injury or incident. If the defendant is liable, the jury typically awards compensatory damages. Compensatory damages, also called economic damages, may be awarded for things such as property damage or monetary loss. Plaintiffs may also seek, and juries sometimes award punitive damages. The jury awards punitive damages when the defendant’s conduct goes beyond negligence to the extent of reckless or malicious behavior (Ghiaridi and Kircher 1995). Punitive damages awards are often large sums and serve the purpose of punishing the defendant and deterring similar behavior in the future. Most states only allow punitive damage awards when the jury first awards compensatory damages; however, some states, such as Alabama and Kentucky, allow juries to award only punitive damages. Although tort reform advocates generally support limitations on punitive damage awards, academic scholarship suggest that punitive damage awards occur very infrequently (Eisenberg et al. 2002). Plaintiffs may also seek and receive non-pecuniary (non-economic) damages, which include awards for emotional injuries, pain and suffering, and loss of life enjoyment. Punitive and non-pecuniary damage awards often draw ire from tort reform advocates due to their subjective and unquantifiable nature.

Institutions

Litigants, lawyers, judges, and jurors all operate within institutional arraignments and societal contexts that structure the decision-making process for each actor. However, since each state controls its own civil courts, institutional arrangements vary by state, and actors in the legal system make choices under very different procedural rules and processes. As such, we might reasonably expect that outcomes will vary across states based on the institutions in place. According to Galanter (1999), tort reform constitutes the most recent and salient change to the civil justice system. Haltom and McCann (2004) maintain that the modern tort reform movement began in the 1970’s as response to a number of expansions in access to the courts, the creation of class action lawsuits, a growth in the size of the legal profession, and social reform movements that engaged in strategic legal mobilization through tort law that altered the “cost, risks, and profits” for corporations and service providers, especially doctors, who had previously benefited from restrictions on lawsuits. In addition to lobbying state and national legislatures and other direct attempts at altering tort law, reformers also engaged in mass media campaigns aimed at creating a cultural perception that tort filers are irresponsible, immoral, and greedy and that plaintiff’s lawyers are dishonest and self-serving (Haltom and McCann 2004). While reformers seek to address several perceived deficiencies in the civil jury system, reforms generally attempt to address two issues, protecting defendants from “frivolous” lawsuits and limiting the size of awards juries can assess against them.

Despite tort reform’s highly salient effect on the civil courts, scholars debate both the causes and goals of the tort reform movement. The American Tort Reform Association (ATRA) is a national organization dedicated to reforming the civil justice system. ATRA’s website states that, “ATRA was founded in 1986 by the American Council of Engineer Companies. Shortly thereafter, the American Medical Association joined them. Since that time, ATRA has been working to bring greater fairness, predictability, and efficiency to American’s civil justice system.”[6] However, Sloan and Chepke (2008) maintain that “[I]t seems unlikely that it [tort reform] is fundamentally about the goals espoused by its proponents, which are said to benefit people in their roles as patients and tax and premium payers (86).” Other scholars are similarly skeptical of reformers purported goals. Yeazell (2018) argues that tort reform emerged in the late 1970s as a partisan political issue due to significant economic changes such as the rise in health care costs and the decline of domestic manufacturing. “Republicans sought to limit civil litigation on the grounds that lawyers and litigation were ruining the country—or at least important swaths of the economy—while Democrats defended litigation and proposed more of it as a solution to one or more problems (83).” While in actuality, it seems that civil litigation served as a scapegoat for both parties’ failure to ensure the public’s access to affordable health care and to protect people from global competition and dangerous products. Moreover, in addition to altering the formal rules, tort reform changed public perception of the civil justice system though a massive public relations campaign, altering both the way jurors evaluate torts and how attorneys practice law (Daniels and Martin 2001, 2004).

Although tort reform affects all aspects of tort law, the academic studies that examine the effect of tort reform, like the political debate surrounding the subject, tend to focus on medical malpractice. Baker (2005) describes what he calls the “Medical Malpractice Myth,” the idea that the vast expansion of medical malpractice lawsuits and pro-plaintiff jury awards, regardless of the merits of the actual case, drive up health care costs for patients and/or force doctors and health clinics out of business. Although Baker and other academic researchers largely reject the myth, medical malpractice remains at the forefront of the tort reform debate. Although the precise reason for tort reform’s focus on medical malpractice is uncertain, it likely stems at least in part from the fact that health care costs continue to rise at rates much higher than average incomes (Buchmueller, Carey, and Levy 2013), and doctor’s malpractice insurance premiums continue to experience cost spikes (Sloan and Chepke 2008; Yeazell 2018).

Much like the discussion about the causes of tort reform, scholars and reformers disagree about the effects of reforms on medical practice. Although research finds that tort reforms decrease the number of tort filings (Avraham 2007; Stewart et al. 2011; Yates, Davis, and Glick 2001) and diminish the size of awards successful parties receive (Dumas 2016; Hyman et al. 2009; Shepherd 2008; Yoon 2001; Zeiler 2010), many scholars disagree about whether reforms achieve their stated goals. Some research shows that tort reforms reduce insurance company loses (Born, Viscusi, and Baker 2009), reduce the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance premiums (Avraham, Dafny and Schanzenbach 2012), and bring down medical malpractice premiums (Danzon, Epstein, and Johnson 2004; Kilgore, Morrisey, and Nelson 2006). Additionally, Avraham and Schanzenbach (2010) maintain that tort reforms increase health insurance coverage by bringing down the cost of private insurance. Yet other scholarship finds that reforms do not bring down medical malpractice insurance premiums (Baker 2005; Sloan and Chepke 2008; Yeazell 2018), consumer costs (Paik et al. 2012; Sloan and Shadle 2009; Zeiler 2010), or consumer risk (Rubin and Shepherd 2007; Shepherd 2008). Others argue that the effect of tort reform varies by the type of reform (Currie and MacLeod 2008).

In addition to debate regarding the effectiveness of tort reforms, scholars also question their normative good (Zeiler 2010). For example, Koenig and Rustad (1995) find that women receive non-economic and punitive damages awards at higher rates than men due to gender differences in the types of injuries male and female litigants sustain; therefore, caps on punitive and non-economic damages disproportionately affect women plaintiffs. Additionally, Finley (2004) shows that women and elderly victims are more likely to experience noneconomic injuries, such as assault, fertility loss, or abuse and are thus disproportionately impacted by noneconomic damage caps, suggesting that tort reforms produce negative consequents for the more vulnerable members of society.

Data and Analyses

Unfortunately, the numerous normative and political debates surrounding civil jury decision-making suffer from a severe lack of reliable empirical data, preventing a rigorous assessment of the claims of either side (Elliot 2004; Galanter 1993; Galanter et al 1994; Saks 1992; Sanders and Joyce 1990; Vidmar 1995). Even though state civil trial courts adjudicate most civil disputes (Galanter 2004), data limitations result in even fewer studies of these courts than their federal district court counterparts. The lack of civil trial court research is especially pervasive in political science where scholars largely study appellate courts, and when political scientists study trial courts, that research typically examines criminal courts. Consequently, these critically important institutions remain under-studied, and policymakers debate and adopt reforms without the aid of comprehensive research.

Unlike all federal court or state appellate court decisions, which are published and publicly available, state civil jury verdicts are often unpublished, unavailable to the public, and not systematically archived at all in several states. Consequently, many studies of civil jury decision-making rely on post-trial interviews and mock jury simulations, or quantitative studies of relatively limited data sources. Although each method of studying jury verdicts contributes to our understanding of trial court behavior, each method possesses benefits and limitations.

Post-trial interviews provide the ability to speak directly with actual jurors; however, these interviews depend on self-reported data that might not adequately reflect jurors’ actual decision-making processes and evaluations (Sommers and Ellsworth 2003). Mock trials often seek to observe the influence of individual juror traits on verdicts. However, scholars critique mock jury research for lacking external validity (Breau and Brook 2007), over-reliance on students (Bray and Kerr 1982; Devin, Clayton, and Dunford 2001; Howard and Leber 1988) and for lacking the depth, detail, and authenticity of actual trials (Bray and Kerr 1982). The use of experimental methods also prevents the exploration of actual trials. On the other hand, scholars critique many quantitative studies that rely on available data sources for their inability to control for case facts, injuries, or quality of representation (Saks 2002).

While not immune from flaws, the data collection for this project improves the quality of civil jury verdict research through the creation of a comprehensive trial court database. Jury verdict reporters provide the primary data source utilized in this study. Jury verdict reporters are independent publications primarily used by attorneys that provide a summary of each civil case, the attorneys for the parties, the judge presiding over the case, the type of case, the type of injury alleged, and the jury verdict. Practicing attorneys use jury verdict reporters to assess what types of cases win, where cases win, and the types of awards juries hand down. The data collection for the volumes runs from November 2008 to November 2009. Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee Reporters were selected, because the editors of these volumes attempt to consistently report every jury verdict in each state based on actual trial records rather than self-reported data.[7] Although the civil trial courts in Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee may or may not necessarily represent the nation’s civil courts, these data provide the most comprehensive source of civil verdicts available.[8] Additionally, these states provide ample variation at the sub-state level on social, political, and economic indicators. These states also provide the opportunity to explore how civil trial courts operate in four states within relative geographic proximity to each other.

Comparing Civil Courts in Four States: Docket Composition, Win/Loss Rates, and Awards

Variation in civil rules, procedures, and outcomes comprised the Federalist’s primary objection to a constitutional mandate protecting civil juries. In Federalist 83, Hamilton highlights the numerous dissimilarities in civil jury selection and civil procedure that existed at the time of the ratification and the potential for inconsistent outcomes. Moreover, current tort reform advocates argue the need for reform to create greater “fairness, predictability, and efficiency (ATRA website).” However, assessing the influences of state-level variation on civil jury verdicts requires previously unavailable comprehensive data. The following research descriptively examines the composition of courts’ dockets, verdicts, institutional structures, and litigant characteristics to assess the extent to which case types and outcomes vary across states.[9] Do these courts adjudicate similar types of cases and reach similar verdicts? If not, what factor might contribute to the variation?

| State | Number of Jury Verdicts | Verdicts of Per Million Persons | Median Award | Maximum Award | % Pro-Plaintiff | % Punitive Damages |

| Alabama | 258 | 56.1 | $30,000 | $33,257,694 | 50% | 6.6% |

| Indiana | 244 | 38.1 | $23,380 | $157,000,000 | 62% | 1.7% |

| Kentucky | 210 | 48.8 | $42,612 | $55,900,000 | 49% | 4.5% |

| Tennessee | 199 | 32.1 | $16,250 | $23,600,000 | 56% | 1.5% |

Table 1 reports the number of verdicts in each state in 2009, verdicts per one million residents (based on the size of the state’s population in 2009 according to the U.S. Census), the median and maximum awards in each state, the percentage of verdicts favoring plaintiffs, and the percentage of verdicts in which the jury awarded punitive damages. In 2009 civil juries in the four states adjudicated 926 civil disputes and awarded $520,491,229 in total damages. Of the five states, Alabama and Kentucky both possess similar population sizes, near 4.5 million residents. Tennessee and Indiana also hold comparable populations near 6.3 million persons. Looking at the verdicts per-million residents indicates that Alabama juries adjudicate more trials per capita than the other three states (56.1 verdicts per million residents), despite having a population smaller than both Tennessee and Indiana. Indiana trial courts rendered the second largest number of verdicts per million persons (48.8). Yet, even in Alabama where civil juries adjudicate the most civil trials, the data show less than 60 trials for every million residents, demonstrating that trials are infrequent events. Overall, a comparison of the number of civil jury verdicts in each state, relative to state population, implies that factors beyond population size determine the number of jury trials in each state.

Awards

Table 1 also reports the median and maximum initial awards compared to the typical award in each state. The data reveal the highly skewed nature of awards (awards in 2009 range from zero dollars to $157,000,000).[10] In order the capture the jury’s evaluation of litigants’ claims, the data set records the jury’s initial award in each case. However, jury awards are often reduced post-trial either through settlement, court action, or appeal (Greene and Bornstein 2003; Ostrom, Hanson, and Daley 1993). Additionally, successful plaintiffs often recover little if any of the actual award (Hans 2008). In an analysis of medical malpractice verdicts in New York City, Vidmar, Grose, and Rose (1998) observe that 44% of all verdicts were reduced post trial, and that on average, plaintiffs received 62% of the jury’s initial award. Although plaintiffs may not receive the jury’s initial award, the median and maximum jury awards provide insight into the typical award in a state and the factors that lead juries to generously compensate plaintiffs.

The smallest median award, only $16,250 occurs in Tennessee. The median award in Alabama is $30,000, while the median awards in Kentucky and Indiana are $42,612 and $23,380, respectively. The median awards in each state suggests that the typical jury award is not especially large. The data also show that juries award punitive damages infrequently. Alabama juries award punitive damages most often of the five states; however, even in Alabama only about 7% of awards include punitive damages. Juries award punitive damages in about 2% of trials in Indiana and Tennessee and in 4.5% of trials in Kentucky.

Obviously, cases involving extremely large awards represent atypical trials; however, the largest award cases provide illustrations of actual litigation where juries delivered million-dollar verdicts, and cases involving very large awards garner the most media attention (Bailis and MacCoun 1996; Garber and Bower 1999). For example, Alabama juries awarded $33,257,694 to the state in State of Alabama v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. et al in which the state claimed that Novartis fraudulently overcharged the state’s Medicaid system for drugs (05-219.52) (Miller AJVR 2009, 412). Novartis charged the state of Alabama the average wholesale prices (AWP) or average wholesale acquisitions costs (WAC) for drugs over a 10-year period. However, the state alleged that the true cost paid by pharmacies and providers was significantly less than that paid by the state. In Novartis’ defense, the company claimed that the state knew that WAC and AWP did not reflect the actual prices charged to wholesalers. Additionally, Novartis maintained that the state possessed the right to audit pharmacies and should have done so. The trial lasted half a month and was appealed to the Supreme Court of Alabama.

The largest award in Indiana occurred in a product liability case. The jury awarded $157,000,000 to the family of a man who was tragically strangled to death when his treestand collapsed while hunting in the case, Estate of Simonton v. L&L Enterprises Inc. (79D01-0602-CT-20) (Miller IJVR 2009, 475). After finding the man hanging from a tree, the plaintiffs, the wife and stepson of the deceased, alleged that the company was liable for the defective treestand. The treestand had been recalled the year before. The company, having previously gone out of business in 2004, did not participate in this litigation. The court granted the estate a default judgment on liability, and the jury issued a verdict on damages only. Although the jury decided to compensate the family, this case presents an example of the type of trial where the plaintiff likely received little if any of the actual award since the business probably possesses few if any resources after going out of business.

Kentucky jurors awarded $55,900,000 ($53,000,000 of the verdict representing punitive damages) to the family of a woman involved in a fatal assault in Wittich v. Flick (08-4294) (Miller KJVR 2009, 581). The case began when two business partners in an optometry office had a business disagreement that apparently became violent. Flick, one of the business partners, invaded his colleague’s home and shot and killed his girlfriend, Wittich. Flick then waited for his partner to return home and shot him as well before being subdued (a Kentucky jury also resolved a civil suit regarding the second shooting in another trial). Wittich’s estate filed suit against Flick, who by this time was serving a life sentence for her murder. However, like the previous example, the deceased’s family is unlikely to obtain the amount awarded from a convicted murderer serving a life sentence.

In Hill v. Moise (000093-06) (Miller TJVR 2009, 288) a Tennessee jury awarded the plaintiff $23,600,000 in a medical malpractice suit. Hill, a woman in her early twenties in 2003, found a lump in her breast and reported it to her Ob-Gyn. After examining the lump in an office visit by palpating the lump, Dr. Moise concluded that the lump was harmless and ran no additional tests. In 2005, during her pregnancy, Hill noticed that the lump appeared larger and visited a second doctor. At that time, medical tests revealed that Hill had breast cancer that had spread to her liver. Hill’s diagnosis at the time of the trial predicted a small chance of survival, and she was physically unable to attend. Hill alleged that Dr. Moise’s failure to perform cancer screening on the lump violated the standard of care and lead to a later diagnosis of the cancer, allowing the cancer to spread and preventing early treatment.

Although the cases where juries handed down the largest awards are atypical when compared to most cases, and it is impossible to generalize from a small, non-random set of cases, these four cases have several features in common. Of the four cases involving the largest awards, there is one medical malpractice case, one product liability, one fraud, and one fatal assault claim. All four cases involve severe injuries. Case injuries include two deaths, a high probability of death, and a claim for a large monetary loss. In three of the four cases, an individual (or an individual’s estate), presumably a party with limited resources in most cases, alleged an injury against the defendant. Additionally, three of the four cases involve a business defendant. At a minimum these cases support previous research showing that awards amounts are not random and rather are correlated with the severity of the plaintiff’s injury (Bovbjerg et al. 1991; Dumas and Haynie 2012; Greene and Bornstein 2003).

Docket Composition

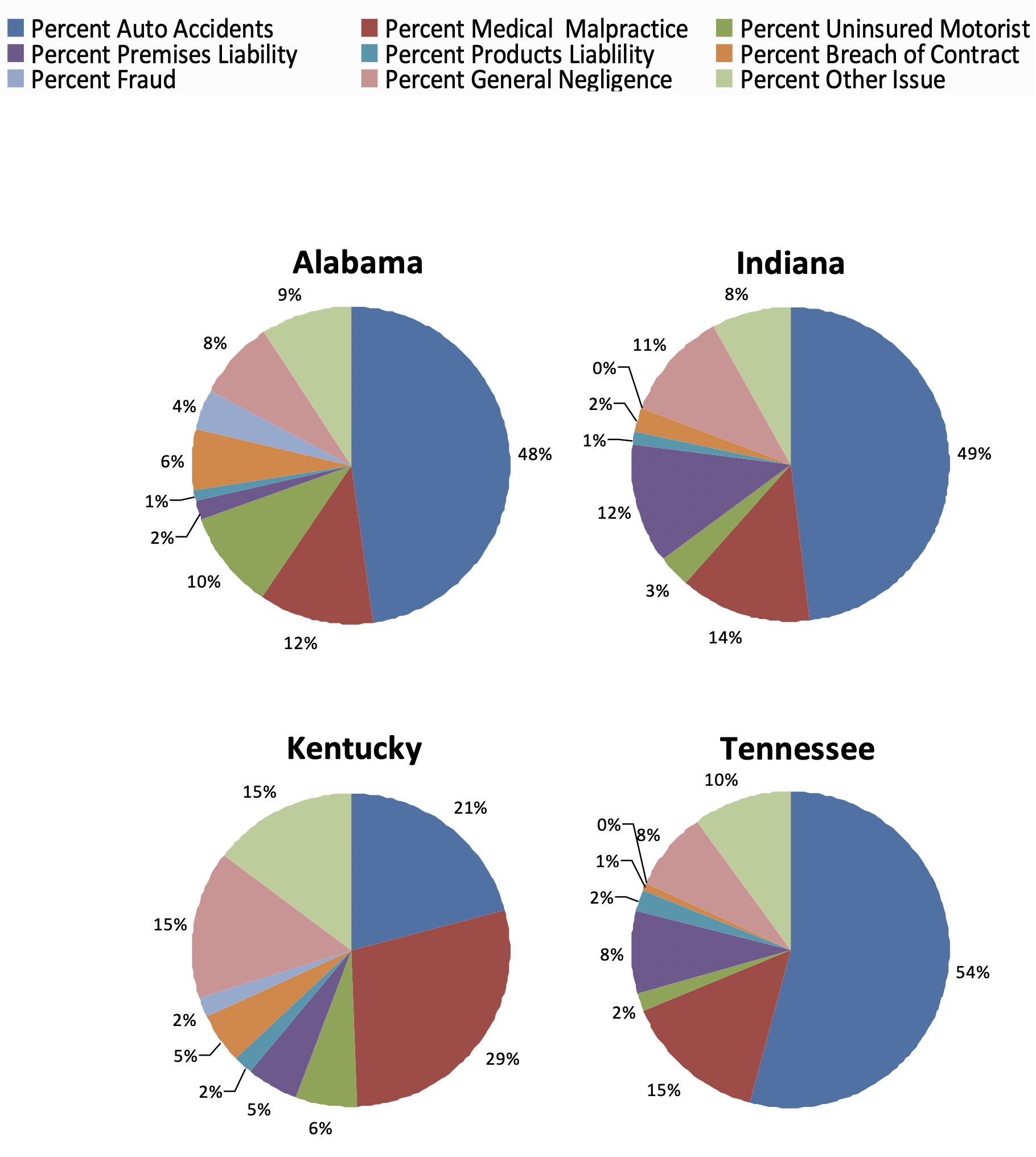

Do juries in the four states decide similar cases? To explore this question, Figure 1 provides a descriptive overview of the 2009 dockets in Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Cases types are aggregated into the seven most common issue areas including auto negligence, premises liability, fraud, medical malpractice, products liability, uninsured motorist, and breach of contract. A general negligence category captures all other types of negligence claims, while an “other issue” category represents cases not captured by any other category. A comprehensive examination of the cases shaping the dockets in the states demonstrates that civil trial courts handle similar case issues; however, the frequency of case types across states varies considerably.

The general public likely recognizes trials involving automobile accidents and medical malpractice, but other case types might be less familiar. For example, premises liability cases involve a plaintiff’s claim that the defendant negligently maintained an unsafe premise. Felix v. Wal-Mart (06-0754) (Miller KJVR 2009, 659) provides an example of typical premise liability case in which a woman slipped and fell on a sticky substance on a Wal-Mart floor and dislocated her hip in the fall. Although Wal-Mart prevailed at trial, the plaintiff argued that Wal-Mart failed to maintain a reasonably safe floor. Products liability cases involve an allegation that the defendant failed to provide a reasonably safe product. In the product’s liability case, Maroney v. Taurus International Manufacturing (07-73) (Miller AJVR 2009, 490), a man sued a gun manufacturer for making and selling an unsafe product when the gun allegedly fired a bullet into the man’s buttocks after falling from the man’s pocket and hitting a cement floor, despite the engaged safety (the jury awarded Maroney $500,000 in compensatory damages and $750,000 in punitive damages).

Uninsured or under-insured motorist cases involve plaintiffs injured in automobile accidents in which the driver at fault lacked insurance or adequate coverage for all the damages. In these cases, the injured plaintiff sues his or her own insurance company for damages caused by the uninsured or under-insured driver. Civil trial courts also examine economic cases such as fraud and breach of contract. The previously discussed case of State of Alabama v. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. et al (Miller AJVR 2009, 412) provides a good example of a fraud trial. A breach of contract trial occurred following the alleged theft of a man’s SUV. When the man made a claim with his insurer for the loss of the stolen vehicle, the insurance company found the theft fraudulent and denied that claim. Although unsuccessful at trial, the man made a breach of contract claim against the insurer in Green v. Allstate Insurance Company (49D06-0606-PL-27082) (Miller IJVR 2009, 380), alleging that company failed to uphold its contractual agreement to insure the vehicle against theft.

Figure 1 shows that trials involving auto accidents make up close to fifty percent of the docket in Alabama (48%), Indiana (49%), and Tennessee (54%). This is consistent with previous scholarship finding that vehicular negligence cases comprise the majority of civil cases (Langton and Cohen 2008; Ostrom et al. 1996). Unlike the other states, only 21% of the trials in Kentucky entail auto accidents. Medical Malpractice cases make up the second largest proportion of the docket in Alabama (12%), Indiana (14%), and Tennessee (15%), and represent the largest segment of the docket in Kentucky (29%). The next largest category of trials varies by state. The dockets of all four states suggest that products liability cases occur infrequently.

Overall, trials involving auto accidents, medical malpractice, and general negligence cases make up the majority of the dockets in all four states. Kentucky civil trial courts adjudicate almost twice as many medical negligence cases as any of the other states. Indiana courts hear considerably more premises liability cases, and Alabama trial courts resolve more economic (fraud and breach of contract) disputes than any other state. Although these data cannot explicate the underlying causal mechanism that generates cases in each state, clear differences emerge in each state’s docket composition.

Outcomes and Awards across Case Issues & Injuries

| Auto Negligence | Premises Liability | Fraud | Medical Malpractice | Products Liability | General Negligence | Uninsured Motorist | Breach of Contract | ||

| Alabama | Pro-plaint

Median Avg. |

38% $0 $771,700 |

64% $35,000 $3,139645 |

64% $35,000 $3,139,645 |

23% $0 $515,001 |

33% $1,250,000 $3,250,000 |

67% $5,000 $336,724 |

73% $20,500 $46,343 |

80% $18,645 $696,429 |

| Indiana | Pro-plaint.

Median Avg. |

84% $10,000 $75,348 |

20% $0 $19,305 |

N/A |

36% $0 $595,001 |

33% $0 $5,230,000 |

48% $0 $606,166 |

75% $66,000 $75,589 |

33% $0 $43,779 |

| Kentucky | Pro-plaint.

Median Avg. |

66% $4,903 $278,172 |

45% $0 $58,494 |

75% $53,338 $6,666,896 |

22% $0 $221,169 |

50% $52,500 $181,275 |

56% $1,500 $54,327 |

69% $5,660 $321,857 |

91% $43,623 $1,053,885 |

| Tennessee | Pro-plaint.

Median Avg. |

68% $6,800 $37,486 |

29% $0 $14,649 |

N/A |

26% $0 $1,453,678 |

25% $1,269,958 $2,277,479 |

50% $545 $660,808 |

100% $13,500 $33,097 |

100% $0 $9,717 |

Next, Table 2 examines winners and awards across case types and reports the percent pro-plaintiff outcomes and the median and mean awards by case type for each of the four states. First, the data show considerable variation in plaintiff wins rates and median awards across states for the same issue areas. For example, plaintiff win rates in auto negligence cases range from 38% in Alabama to 68% in Tennessee, while median awards range from $0 in Alabama to $10,000 in Indiana. On the other hand, the data show that plaintiffs consistently encounter considerable difficulty when pursuing premises liability and medical malpractice cases in all four states, as evidence by the low percentages of plaintiff wins. Plaintiffs also win over 70% of uninsured motorist cases in all four states. Given that each uninsured motorist case involves an injured individual suing his/her insurance company, the considerably higher win rates in this category might support the “deep pockets” hypothesis, which suggests that juries treat corporate and business defendants more harshly due to their perceived greater ability pay (Bornstein and Rajki 1994; Dumas and Haynie 2012; Hans 2000). Furthermore, the table shows that the median award for several issue areas and states is no award, indicating that half of the plaintiffs in these cases receive no compensation. Interestingly, zero dollars is the median award in medical malpractice cases for all four states, and the average medical malpractice award in each state ranges from $515,000 in Alabama to $1.5 million in Tennessee. Given that medical malpractice cases often feature seriously injured parties, typical jury awards in these cases appear lower than the medical malpractice debate might imply. On the other hand, products liability cases tend to produce low plaintiff award rates, but relatively large awards. Taken together verdicts across the states evidence both considerable variation and consistency. Plaintiff win and award rates differ noticeably across issue areas and across states; however, jurors in each state are most supportive of plaintiffs in uninsured motorist cases and least supportive in premises liability and medical malpractice cases.

| Alleged Injury | Alabama | Indiana | Kentucky | Tennessee | Total |

| Property Loss/Damage | 23 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 34 |

| Monetary Loss | 32 | 10 | 25 | 2 | 69 |

| Emotional | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 16 |

| Broken Bone(s) | 8 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 56 |

| Death | 25 | 22 | 21 | 11 | 82 |

| Injury Required Surgical Repair | 22 | 26 | 24 | 11 | 84 |

| Slip and Fall | 1 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 25 |

| Soft Tissue | 32 | 51 | 31 | 84 | 200 |

| Other Physical Injuries | 111 | 96 | 76 | 57 | 270 |

| Other Non-Physical Injuries | 3 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 92 |

To further examine how case facts effect verdicts, I also code for eight injury categories ranging from emotional and soft tissue (scratches, bruises, and whiplash, etc.) to extreme injuries such as paralysis and death. Table 3 reports the frequencies of alleged injuries in cases coming before civil juries across the states. Interestingly, while the data show substantial variation in case occurrence across states, the results suggest that the frequency of alleged injuries in civil trials is relatively evenly distributed. Although previous research finds that soft tissue injuries garner less compensation than other types of injuries (Bovbjerg et al. 1991), suffer from a lack of familiarity among the general public (Hans 2008), and are often viewed as illegitimate (Hans 2008), soft tissue injuries are the most frequent type of injury in civil trials in the five states (195 total cases, combined). While the data cannot explain the prevalence of soft tissue injuries in civil trials, soft tissue injuries might simply occur more commonly than other injuries. On the other hand, the difficulty in proving a soft tissue injury might encourage cases involving soft tissue symptoms to go to trial rather than settling beforehand. The second and third most frequent injuries occur in cases in which the plaintiff underwent a surgery as a result of an accident or died. Injuries involving broken bones are the fourth most common in all states. Combined, physical injuries account for 77.2% of civil trials (712 our 923 cases). The most interesting difference between states is the far greater frequency of property and monetary disputes in Alabama. While the other states appear to decide cases involving economic injuries relatively infrequently, Alabama juries decide a comparatively large number of these cases in a given year.

Litigants

| State | Individual v. Individual | Individual v. Business | Individual v. Government | Individual v. Other Defendant |

|

Alabama Pro-plaintiff |

54.2% (45%) |

30% (60%) |

0 |

1.2% (66%) |

|

Indiana Pro-plaintiff |

62.7% (70%) |

19.7% (46%) |

2.7% (43%) |

2.5% (67%) |

|

Kentucky Pro-plaintiff |

45.5% (48%) |

36% (43%) |

4.7% (10%) |

1% (100%) |

|

Tennessee Pro-plaintiff |

62.3% (62%) |

26.6% (53%) |

2.5% (40%) |

1.5% (33%) |

|

All States Pro-plaintiff |

56% (57%) |

28% (55%) |

2% (32%) |

2% (64%) |

In evaluating who participates in litigation, I code each plaintiff and defendant as an individual, business, or government. Remaining classes of litigants such as organizations or estates are coded as “other.” This coding scheme is consistent with prior studies. Examining the types of litigants participating in civil trials and pro-plaintiff verdicts across the states in Table 4, the data demonstrates that the vast majority of all cases involve an individual plaintiff suing an individual defendant.[11] The next largest category of litigants entails individuals seeking damages from business defendants. Only 4% of cases involve an individual challenging the government or any other class of defendant. Individual plaintiffs, Galanter’s prototypical “have-nots,” account for 88% of plaintiffs in the four states. The distribution of litigant classes across states suggests that the combinations of litigants involved in civil trials are fairly consistent across states.

When we examine how “have-not” plaintiffs fair against “have” defendants, the data shows that “have-nots” appear to do somewhat better than theory would expect. The data also implies that the contingency fee system does allow “have-not” plaintiffs to obtain quality representation. Although plaintiffs do not appear to suffer an overwhelming disadvantage in any state, the data supports the dominance of the government in court cases (Kritzer 2003), evidenced by the very low plaintiff success rates when the government is the defendant.

Institutions & Tort Reforms

| State | Judicial Selection Method | Punitive Damage Caps | Non-economic Damage Caps | Collateral Source Rule | Joint & Several Liability | Frivolous Lawsuit Penalties | Total # of Tort Reforms Enacted | Institutional Review Board | Comparative Fault |

| Alabama | Partisan Elections | X | X | X | X | X | 29 | ||

| Indiana | Mixed | X | X | X | 16 | X | X | ||

| Kentucky | Non-Partisan | X | X | 12 | X | ||||

| Tennessee | Partisan | X | X | X | X | 25 | X |

Finally, I examine institutional variation across states. While courts in each state appear to adjudicate similar case issues with similar litigants, each court operates under very different institutional frameworks. If institutional rules and frameworks affect the decision calculus for actors in their respective legal systems as previous research suggests (Brace and Hall 1990), variation across states might at least partially explain varying court dockets and trial outcomes across sates. Table 5 reports the institutional arrangements explored in this study. Although the influence of judicial selection and retention methods on trial court behavior remains understudied, previous research demonstrates that judicial selection and retention methods strongly influence decision-making at the state supreme court level, especially in highly salient cases (Brace and Hall 1990, 1993; Brace and Boyea 2008; Caldarone, Canes-Wrone, and Clarke 2009; Canes-Wrone, Clark, and Park 2012). If judges shape jury decision-making through their rulings or courtroom demeanor, jury verdicts might vary across judicial selection and retention mechanisms. In fact, Rowland, Traficanti, and Vernon (2010) argue, that every jury trial is actually a bench trial. “What the constitutional right to a jury trial actually guarantees citizens is the right to a trial in which a jury decides a dispute largely defined and engineered by the exercise of judicial discretion (for a detailed discussion of judicial selection in each state’s trial courts, see Appendix A).” (186).

Furthermore, the method states use to determine fault in the jury decision-making process constitutes a significant institutional difference between states. Juries in states utilizing comparative fault can adjust awards to offset the plaintiff’s contributing negligence. Defense verdicts can also occur in states that use comparative fault in cases in which the jury assesses plaintiff fault over a certain threshold, usually when the jury assess more than 50% fault to the plaintiff. In Alabama, civil courts rely on the contributory negligence standard to determine fault where jurors use a two-stage process to determine fault. First, jurors must determine if the defendant is negligent. If jurors find the defendant negligent, they then decide if the plaintiff contributed in any way to his or her injury. Under contributory negligence, if the plaintiff was even 1% at fault, the plaintiff cannot recover damages.

State tort reform adoptions seek to deliberately reshape how trial courts reach decisions, as such we would expect that the adoption of various tort reforms to alter trial outputs. Although much of the debate surrounding tort reform focuses on medical malpractice, states largely adopt general reforms that affect outcomes for all tort cases (for more detail about tort reform in these states, see Appendix B). Table 5 reports whether each stated adopted the five most common tort reforms (Schmidt, Browne, and Lee 1997).[12] On the other hand, the Medical Review Board reform seeks to specifically address medical malpractice cases.

Advocates of tort reform often favor the creation of medical review boards, panels of medical experts, to independently review the merits of medical malpractice claims prior to a formal trial to prevent “meritless” cases from reaching trial. Half of US states have enacted medical malpractice review panels (Nathanson 2004). Review panels vary by state, but panels generally comprise 3-7 members, often one may be an attorney, another a health care provider, and/or judge, and some include lay persons. Although more informal than a trial, panels can subpoena witnesses and documents, hear testimony, and make an initial malpractice ruling (Sloan and Chepke 2008). The state of Indiana requires that all plaintiffs alleging medical malpractice take their claims before an institutional review board prior to trial. Although the board’s decision is not binding, the board’s determination is admissible as evidence at the trial and likely significantly influences the plaintiff’s chances of success at trial. The review board first determines if a breach in the standard of care occurred in the plaintiff’s treatment. Then, if the board finds a breach in the standard of care, the board determines whether that deviation in care caused the plaintiff’s injury.

| Review Board Decision | Plaintiff Verdicts Out of the Total | % Pro-Plaintiff Verdicts |

| For the Plaintiff | 6/7 | 85.7% |

| Mixed Decision | 1/6 | 16.7% |

| For the Defense | 4/16 | 25% |

In 2009 Indiana juries decided 33 medical malpractice cases. Of those, the reporter provides the review boards’ decision in 29 trials. Table 4 shows the review boards’ decisions and the corresponding jury verdicts. The table reports cases in which the review issued a unanimous vote in favor of the plaintiff; in other words, the board determined that the doctor or medical facility breached the standard of care, causing the plaintiff’s injury. Mixed decisions occur when the board cannot agree on one or both parts of the decision. Decisions in favor of the defense result when either the board unanimously agrees that the doctor or medical facility upheld the standard of care, or that the breach in the standard of care was causally unrelated to the plaintiff’s injury.Overall, plaintiffs in Indiana won 11 out of 29 medical malpractice cases tried in the state in 2009. However, examining the table indicates that of the seven cases in which the review board found that a breach in the standard of care was causally related to the injury, plaintiffs won 6 (85.7%). Although the board found in favor of the plaintiff in only six cases, the plaintiffs’ success rates in those cases are substantially higher than the overall success rates for plaintiffs pursuing medical malpractice claims. On the other hand, the observations suggest that the review board issues considerably more verdicts in favor of the defense and mixed opinions than decisions in favor of the plaintiff. Sixteen decisions of the Institutional Review Board favored the defense while 6 were mixed decisions. However, it appears that even mixed decisions from the review board hurt plaintiffs’ changes of success. When the board issued a mixed decision, juries decided only one out six cases (16.7%) in favor of the plaintiff. Interestingly, juries delivered more pro-plaintiff verdicts in trials where the board found against the plaintiff than in cases with mixed decisions from the board. Of cases in which the board found no breach in the standard of care or no injury to plaintiff as a result of the breach, plaintiffs won 4 of 16 trials (25%).

Discussion

These data provide the most comprehensive database of civil trials to date, allowing for an in-depth investigation of the dockets, case outcomes, issues and injuries, and litigants in the civil jury trials in each state. Examining courts’ dockets comprehensively shows that the types of cases adjudicated do not vary considerably across the states; however, the percent of the docket allocated to each issue area changes considerably from state to state. Additionally, factors beyond the population size appear to determine the volume of cases adjudicated in each state. Descriptive comparison of jury verdicts across states also provides evidence that considerable variation occurs between states in terms of who wins and who loses, and how much successful parties receive. But, is variation good or bad? Should we continue to rely on juries to make important dispute resolution and resource allocation decisions? The answer depends in part on what society expects from juries. If one is concerned with consistency, like the Federalists, the results provide evidence to support their gravest concerns. On the one hand, those that favor allowing lay people to solve disputes and determine damages argue that juries apply community values. Under this view, one could consider variation from one community to another as evidence that juries are functioning as they should. However, the significant difference in institutional arrangements from one state to the next likely accounts for at least a portion of the observed variation in outcomes. States vary in terms of the tort reforms enacted, the method used to select and retain judges, and the fault standards juries apply, etc. All these factors likely contribute to differences in litigant outcomes across states. Although additional research is need to more fully discern how state institutions affect litigant outcomes, the data provide support for the Federalists’ contention that states employ dissimilar systems of civil law, engendering variable outcomes. As long as states adopt widely dissimilar civil justice systems, juries will likely continue to reach disparate verdicts. Ironically, tort reform, despite its champions’ promises of greater consistency, might actually yield the unintended consequence of producing greater variation in court outcomes as states adopt different types and numbers of reforms.

On the other hand, the data evidence several similarities between courts in each state and suggest reasons for optimism, even for those critical of the civil justice system. Despite differences in docket composition, auto negligence and medical malpractice cases encompass most trials in each state. However, plaintiffs garner comparatively few wins in medical malpractice cases in each state. For those concerned that juries award large sums to sympathetic plaintiffs who suffer medical injuries, regardless of the merits of their cases, these results should assuage some of their concerns. On the other hand, the data provide cause for apprehension for those who worry that victims of medical malpractice have little recourse. Moreover, awards appear sensitive to both injury severity and perceived resources. The data suggest that juries’ awards are not as capricious as some reformers suggest; however, wealthy defendants may well pay more when the they lose. Investigating the participants in civil litigation shows that individuals are the most frequent participants in civil litigation, and they initiate the majority of civil trials. Fifty-six percent of trials involve an individual suing another individual, and 88% of all trials involve an individual plaintiff. However, plaintiff win rates imply that plaintiffs with strong cases can obtain quality representation and offset at least some of the resource imbalances they might suffer.

Obviously more research is needed to better ascertain the connection between institutions and jury verdicts and explain the causes of case outcome variability. Yet the evidence presented here provides both causes for optimism and trepidation, depending on one’s side of the debate. Whether or not we choose to continue to entrust civil juries to settle disputes, right wrongs, and punish wrongdoers with monetary compensation, depends on what we want our civil justice system to do and who we want to make these decisions. Although adoption of national reforms might produce greater consistency in outcomes, to the pleasure of Federalists and tort reformers, taking the authority away from states and local jurors would undoubtably limit the ability for states and community members to settle disputes for themselves as Anti-Federalists initially fearer. Furthermore, if we take decision-making power away from juries, who should we entrust? Ultimately, questions over individuals’ and groups’ rights to sue for damages and have their grievances redressed by a court are fundamental questions about justice and politics that will hopefully be decided on more comprehensive future research.

References

Allen, Michael P. 2006. “A Survey and Some Commentary on Federal Tort Reform.” Akron Law Review 39(4): 909-41. (↵ Return)

Avraham, Ronene. 2007. “Current Research on Medical Malpractice Liability.” Journal of Legal Studies 36:183–212. (↵ Return)

Avraham, Ronen, Leemore S. Dafny, and Max M. Schanzenbach. 2012. “Does Tort Reform Reduce Health Care Costs?” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 28(4): 657-86. (↵ Return)

Avraham, Ronen, and Max Schanzenback. 2010. “The Impact of Tort Reform on Private Health Insurance Coverage.” American Law and Economics Review 12(2): 319-55. (↵ Return)

Bailis, Daniel S. and Robert J. MacCoun. 1996. “Estimating Liability Risks with the Media as Your Guide: A Content Analysis of Media Coverage of Tort Litigation.” Law and Human Behavior 20: 419-29. (↵ Return)

Baker, Tom. 2005. The Medical Malpractice Myth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Baum, Lawrence. 1998. American Courts. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. (↵ Return)

Baxter, William. 1980. “The Political Economy of Anti-Trust.” In The Political Economy of Antitrust, ed. Robert Tollison. Lexington: Lexington Press. (↵ Return)

Buchmueller, Thomas, Colleen Carey, and Helen G. Levy. “Will Employers Drop Health Insurance Coverage Because of The Affordable Care Act?.” Health Affairs 32.9 (2013): 1522-1530. (↵ Return)

Born, Patricia, W. Kip Viscusi, and Tom Baker. 2009. “The Effects of Tort Reform on Medical Malpractice Insurers’ Ultimate Losses.” Journal of Risk and Insurance 76(1): 197-219. (↵ Return)

Bornstein, Brian H., and Michelle Rajki. 1994. “Extra-Legal Factors and Product Liability: The Influence of Mock Jurors’ Demographic Characteristics and Intuitions about the Cause of an Injury.” Behavioral Science & the Law 12(2): 127–47. (↵ Return)

Bovbjerg, Ronald R., Frank A. Sloan, Avi Dor, and Chee Ruey Hsieh. 1991 “Juries and Justice: Are Malpractice & Other Personal Injuries Created Equal?” Law & Contemporary Problems 54(1): 5-42. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Brace, Paul and Brent D. Boyea. 2008. “State Public Opinion, the Death Penalty, and thePractice of Electing Judges.” American Journal of Politics 52: 360-72. (↵ Return)

Brace, Paul, and Melinda Gann Hall. 1990. “Neo-Institutionalism and Dissent in State Supreme Courts. Journal of Politics 52: 54-70. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

____1993. “Integrated Models of Judicial Dissent.” Journal of Politics 55: 914-935. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Bray, Robert M. and Norbert L. Kerr. 1982. “Methodological Considerations in the Study of the Psychology of the Court.” In The Psychology of the Courtroom, Norbert L. Kerr and Robert M. Bray, eds.. New York: Academic Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Breau, David L. and Brian Brook. 2007. “’Mock’ Mock Juries: A Field Experiment on the Ecological Validity of Jury Simulations.” Law and Psychology Review 31: 77-92. (↵ Return)

Burke, Thomas F. 2002. Lawyers, Lawsuits, and Legal Rights: The Battle over Litigation in American Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. (↵ Return)

Caldarone, Richard P., Brandice Canes-Wrone, and Tom S. Clark. 2009. “Partisan Labels and Democratic Accountability: An Analysis of State Supreme Court Abortion Decisions.” Journal of Politics 71(2): 560-73. (↵ Return)

Canes-Wrone, Brandice, Tom S. Clark, and Jee-Kwang Park. 2012. “Judicial Independence and Retention Elections.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 28(2): 211-34. (↵ Return)

Chapman, Nathan Seth. 2007. “Punishment by the People: Rethinking the Jury’s Political Role.” Duke Law Journal 56(4): 1119-57. (↵ Return)

Currie, Janet, and W. Bentley MacLeod. 2008. “First Do No Harm? Tort Reform and Birth Outcomes.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(2): 795-830. (↵ Return)

Daniels, Stephen, Joanne Martin. 2000. “The Impact it has Had Is between People’s Ears: Tort Reform, Mass Culture, and Plaintiff’s Lawyers. DePaul Law Review 50(2): 453-96. (↵ Return)

Daniels, Stephen, Joanne Martin. 2001. “‘We Live on the Edge of Extinction All the Time’: Entrepreneurs, Innovations, and the Plaintiffs’ Bar in the Wake of Tort Reform.” Legal Professions: Work, Structure and Organization, ed. Jerry Van Hoy, 149-80. New York: JAI/Elsevier Science Ltd. (↵ Return)

Daniels, Stephen, Joanne Martin. 2002. “It Was the Best of Times, It Was the Worst of Times: The Precarious Nature of Plaintiff’s Practice in Texas.” Texas Law Review 80: 1781-828. (↵ Return)

Daniels, Stephen, Joanne Martin. 2004. “The Strange Success of Tort Reform.” Emory Law Journal 53(3): 1225-62. (↵ Return)

Daniels, Stephen and Joanne Martin. 2015. Tort Reform, Plaintiff’s Lawyers, and Access to Justice. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press. (↵ Return)

Danzon, Patricia M., Andrew J. Epstein, and Scott Johnson. 2004. “The Crisis in Medical Malpractice Insurance.” In Brookings-Wharton Papers on Financial Services, eds. R. Herring and R. Litan. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. (↵ Return)

Devin, Dennis J., Laura D. Clayton, Benjamin B. Dunford, Ramsy Seying, and Jennifer Pryce. 2001. “Jury Decision Making: 45 Years of Empirical Research on Deliberating Groups.” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 7(3): 622-727. (↵ Return)

Dumas, Tao L. 2016. “Contextualizing the Black Box: State Institutions, Trial Context & Civil Jury Verdicts.” Journal of Law and Courts 4(2): 291-312. (↵ Return)

Dumas, Tao L. & Stacia L. Haynie. 2012. “Building an integrated model of trial court decision making: Predicting plaintiff success and awards across circuits.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 12(2): 103-26. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Dumas, Tao L., Stacia L. Haynie, and Dorothy Daboval. 2015. “Does Size Matter? The Influence of Law Firm Size on Litigant Success Rates.” Justice System Journal 36(4): 341-54. (↵ Return)

Eisenberg, Theodore. 1990. “Testing the Selection Effect: A New Theoretical Framework with Empirical Tests.” Journal of Legal Studies 19(2): 337-58. (↵ Return)

Eisenberg, Theodore, Neil LaFountain, Brian Ostrom, David Rottman, and Marin T. Wells. 2002. “Juries, Judges, and Punitive Damages: An Empirical Study.” Cornell Law Review 87(3): 743-768. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Eisenberg, Theodore and Charlotte Lanvers. 2009. “What is the Settlement Rate and Why Should We Car?” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 6(1): 111-46. (↵ Return)

Elliot, Cary. 2004. “The Effects of Tort Reform: Evidence from the States.” Congressional Budget Office, Microeconomic and Financial Studies Division. www.cbo.gov (↵ Return)

Engel, David M. and Eric H. Steele. 1979. “Civil Cases and Society: Process and Order in the Civil Justice System.” American Bar Foundation Research Journal 4(2): 295-346. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Farole, Donald J., Jr. 1999. “Reexamining Litigant Success in State Supreme Courts.” Law & Society Rev. 33(4): 1043–58. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Finley, Lucinda M. 2004. “The Hidden Victims of Tort Reform: Women, Children, and the Elderly.” Emory Law Journal53(3): 1263-14. (↵ Return)

Galanter, Marc. 1974. “Why the ‘haves’ come out ahead: Speculations on The Limits of Legal Change.” Law & Society Review 9(1): 95-160. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Galanter, Marc. 1993. “News from Nowhere: The Debased Debate on Civil Juries.” Denver University Law Review 71(1): 77-113. (↵ Return)

Galanter, Marc. 1999. “Farther Along.” Law & Society Review 33(4): 1113–23. (↵ Return)

Galanter, Marc. 2004. “The Vanishing Trial: An Examination of Trial and Related Matters in Federal and State Courts.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 1(3): 459-570. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Galanter, Marc, Bryant Garth, Deborah R. Hensler, and Frances Kahn Zemans. 1994. “How to Improve Civil Justice Policy.” Judicature 77(4): 77-113. (↵ Return)

Garber, Anthony G. and Bower. 1999. “Newspaper Coverage of Automotive Product Liability Verdicts.” Law and Society Review 33(1): 93-122. (↵ Return)

Ghiaridi, James D, and John J. Kircher. 1995. Punitive Damages: Law and Practice. Deerfield, IL: Clark, Boardman, and Callaghan. (↵ Return)

Goldman, Lawrence. 2008. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay: The Federalist Papers. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Greene, Edie and Brain Bornstein. 2003. Determining Damages: The Psychology of Jury Awards. Washington D.C.: The American Psychological Association. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Haddon, Phoebe A. 1994. “Rethinking Jury.” William and Mary Rights Journal 3: 29-106. (↵ Return)

Haltom, William, and Michael McCann. 2004. Distorting the Law: Politics, Media, and The Litigation Crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Hans, Valerie P. 2000. Business on Trial. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. (↵ Return)

Hans, Valerie P. 2008. “Faking It? Citizen Perceptions of Whiplash Injuries.” In Civil Juries and Civil Justice: Psychological & Legal Perspectives, Bornstein et al. eds. New York: Springer. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Heinz, John P., EdwardO. Laumann, Robert L. Nelson, and Ethan Michelson. 1998. “The Changing Character of Lawyers’ Work: Chicago in 1975 and 1995.” Law & Society Review 32(4): 751–76. (↵ Return)

Helland, Eric, Daniel M. Klerman, and Yoon-Ho Alex Lee. 2017. “Maybe there’s No Selection Bias in the Selection of Disputes for Litigation.” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economic 20(2): 382-459. (↵ Return)

Howard, Judith A. and B. Douglas Leber. 1988. “Socializing Attribution: Generalizations to ‘Real Social Environments.” Journal of Applied Psychology 8(18): 664-87. (↵ Return)

Hylton, Keith N. 1993. “Asymmetric Information and the Selection of Disputes for Litigation.” Journal of Legal Studies22(1): 187-210. (↵ Return)

Hyman, David A., Bernard Black, Charles Silver, and William M. Sage. 2009. “Estimating the Effect of Damages Caps in Medical Malpractice Cases: Evidence from Texas.” Journal of Legal Analysis 1(1): 355–409. (↵ Return)

Jonakait, Randolph N. 2006. The American Jury System. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. (↵ Return)

Lasswell, Harold. 1950. Politics: Who Gets What, When, and How. New York: P. Smith. (↵ Return)

Karsten, Peter. 1997. “Enabling the Poor to Have their Day in Court: The Sanctioning of Contingency Fee Contracts, a History to 1940.” DePaul Law Review 47(2): 231-60. (↵ Return)

Kinsey, Karl A., and Loretta J. Stalans. 1999. “Which ‘Haves’ Come out Ahead and Why? Cultural Capital and Legal Mobilization in Frontline Law Enforcement.” Law & Society Review 33(4): 993-1023. (↵ Return)

Koenig, Thomas, and Michael Rustad. 1995. “His and Her Tort Reform: Gender Injustice in Disguise.” Washington Law Review 70(1): 1-90. (↵ Return)

Kessler, Daniel, Thomas Meites, and Geoffrey Miller. 1996. “Explaining Deviations from the Fifty Percent Rule: A Multimodal Approach to the Selection of Cases for Litigation.” Journal of Legal Studies 25(1): 233-59. (↵ Return)

Kritzer, Herbert M. 1990. The Justice Broker: Lawyers and Ordinary Litigation. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

————1991. Let’s Make a Deal: Understanding the Negotiation Process in Ordinary Litigation. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. (↵ Return)

——1997-98. “Contingency Fee Lawyers as Gatekeepers in the Civil Justice System.” Judicature 81(1): 22-29. (↵ Return)

——2003. “The Government Gorilla: Why Does Government Come Out Ahead in Appellate Courts?” In, In Litigation: Do the “Haves Still Come Out Ahead?,” Herbert M. Kritzer and Susan Silbey, eds. Stanford: Stanford University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)