Chapter 1: Actors in the Judicial Process

1.6 The Transmission of Legal Precedent in the U.S. Court of Appeals

Kristen M. Renberg

The published opinions by a US Court of Appeals are replete with citations to legal precedents—precedents from the US Supreme Court, from within their own circuit, and from the court of appeals in their sister circuits. The first two types of citation are easy to explain, as precedents from the US Supreme Court and from their circuit are binding. However, precedents from other appellate courts in other jurisdictions are not. How does a judge choose whether to cite such nonbinding precedents when authoring an opinion? Will a judge cite precedents published by courts that are institutionally similar to hers? Alternatively, does a judge prefer to cite precedents that were authored by other judges with whom they share similar characteristics? This chapter seeks to answer these questions by identifying the judge-level characteristics (race, gender, and partisanship) along with court-level characteristics (internal procedural rules) in these cases to understand under what conditions we observe the transmission of precedent from one court of appeals to another.

It is critical to understand how and why precedents travel from one circuit to another. In most cases, the court of appeals will make the final decision in a case and on an issue of law. The finality of these decisions has increased as the US Supreme Court has decreased its caseload over the past few decades. On average, the current Supreme Court now resolves around seventy-five cases a year, whereas the courts of appeals resolve more than fifty thousand cases a year. The Supreme Court hears less than 2 percent of the cases appealed to it, and less than 15 percent of the cases resolved by the courts of appeals are appealed to the Supreme Court (Cross 2007, 2). Given this, a large proportion of the cases resolved by courts of appeals as well as the precedents they produce are left untouched by the Supreme Court and are deserving of rigorous study in judicial politics.

Following in the path of several scholars (Walker 1969; Canon and Baum 1981; Landes and Posner 1976; Caldeira 1985; Fowler and Jeon 2008; Landes, Lessig, and Solimine 1998), I rely on network analysis to understand interdependent relationships in the judiciary. There are many reasons why treating citations as a network makes sense. The main reason is that citations within opinions do not occur independently. For example, a judge can observe which precedents were previously cited, and this may influence her decision to cite a given precedent. Likewise, we may expect that a judge is more likely to cite a precedent if she has previously cited the precedent. Further, some judges have cultivated prominent reputations; therefore, the opinions they author are cited more frequently as compared to other judges. For these reasons, network analysis is an appropriate methodological approach for understanding and modeling who cites precedents from whom.

Courts of Appeals

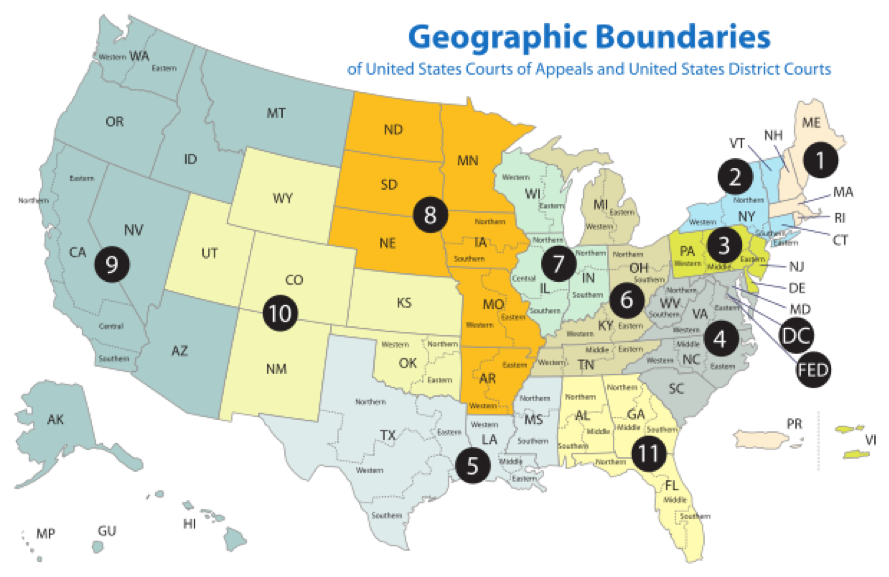

Sitting directly below the US Supreme Court, the court of appeals are usually considered the second-highest tier of federal courts in the United States. There are thirteen federal judicial circuits within the United States. Eleven of the circuits are characterized as regional, since their jurisdictions often cover multiple states. The District of Columbia (DC) Circuit has jurisdiction over the United States’ capital, which makes it somewhat different from its sister circuits in terms of caseload and jurisdiction. While the DC Circuit is unusual when compared to the other eleven regional circuits, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (FED) is really a different animal—this court has nationwide jurisdiction to hear appeals in specialized cases.

Each federal circuit has a single appellate court and multiple district courts. These courts of appeals have mandatory and appellate jurisdiction. As such, the courts of appeals do not have to review every decision made by the district courts in its circuit; however, it does mean a court of appeals must review if an appeal is submitted. Losing parties at the courts of appeals have two options: they can seek a hearing from the US Supreme Court or they can request an en banc review. An en banc review is when all or a majority of active judges from the circuit hear the appeal. Requests for en banc review are rare and infrequently granted. Figure 1 displays a map of the geographic boundaries of the federal judicial circuits.

Legal Precedent

Courts of appeals resolve cases through panels composed of three randomly assigned judges. If the judges decide to issue an opinion, one of the three judges is tasked with authoring the majority coalition’s opinion. If that opinion is published, it becomes a binding precedent and guides future legal decisions by appellate and district judges within the circuit (Aldisert 1989, 632; Hinkle 2017; Caminker 1994). Precedents are born out of legal opinions and establish either a principle or rule. Opinions published by one court of appeals are not binding over decisions in other courts of appeals, and not all opinions are published. An unpublished opinion resolves only the specific legal issue in the case before the court. The decision to publish an opinion is highly relevant for the judge who authored the opinion and judges from her circuit, as the choice to publish is also a de facto decision to establish a precedent and constrain future decisions.

Again, precedents are meant to guide future decision-making. This legal norm is known as stare decisis, which translates from Latin into “to stand by things decided.” Judges are expected to rely on previous binding decisions when crafting their opinion in a similar case. Epstein and Knight describe this process: “If judges want to establish a legal rule of behavior that will govern the future activity of the members of the society in which the court exists, they will be constrained to choose from a set of rules that the members of the society will recognize and accept” (1998, 164). As such, reliance on precedents provides many institutional benefits. The norm of stare decisis leads to reasonable expectations and stability in decisions made by different judges (Lee 1999; Caminker 1994; Rasmusen 1994). Stare decisis does not limit the law from evolving as society changes; however, it does lead to law evolving incrementally on a case-by-case basis (Kozel 2012). From an outsider’s perspective, having a precedent guide a judge’s decision makes the verdict appear more legitimate. Finally, and most importantly for the operation of courts, stare decisis promotes efficiency by expediting the decision-making and opinion-writing processes for judges (Lee 1999; Caminker 1994).

Within the judiciary, we observe two forms of stare decisis: vertical and horizontal. Vertical stare decisis is based on the hierarchy of the judiciary, where precedents by higher courts supersede precedents by lower courts. Horizontal stare decisis occurs when a precedent transmits across courts that are on the same tier of the judicial hierarchy. For example, a federal district court in California is in the Ninth Circuit. Due to the norm of vertical stare decisis, the district court needs to adhere to precedents established by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Likewise, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and the federal district court in California must adhere to precedents established by the US Supreme Court. Under the norm of horizontal stare decisis, the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, for example, needs to adhere to precedents previously established on the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

Judicial politics research has traditionally focused on vertical stare decisis, arguing that lower courts will almost always be compliant with Supreme Court precedents (Klein 2002; Songer, Segal, and Cameron 1994; Songer and Sheehan 1990; Caminker 1994; and Westerland et al. 2010). Benesh and Reddick (2002), for example, conducted an event-history analysis and observed that following the overruling of a precedent by the Supreme Court, lower courts quickly adopted the new precedent and stopped relying on the overruled precedent.

This chapter focuses on horizontal stare decisis, specifically the transmission of precedent from one court of appeals to another. When a court of appeals relies on a precedent that was determined in a separate appellate court, the transmitted precedent is influencing a case outside of its jurisdiction through persuasion rather than normative binding influence. Some scholars have argued that these citations are evidence of strategic considerations by the judge who authored the opinion (e.g., Calderia 1985). This vein of the literature postulates that when a judge cites a precedent that was published outside of her jurisdiction, she is attempting to provide evidence that her argument is widely supported and intellectually grounded (Hume 2009). Others have suggested that these transmitted citations are a product of the different reservoirs of precedents among the courts of appeals. In other words, some courts may have more experience and therefore a more extensive stock of precedents relating to a specific legal issue than other courts (Solberg, Emrey, and Haire 2006).

Empirically, some scholars have viewed the act of transmitting precedents across courts as a signal of prestige, suggesting that the more often a precedent is cited in opinions by other courts, the more influential the judge who authored the precedent is. Landes, Lessig, and Solimine (1998) created a total influence measure based on the number of citations a judge’s opinion received from her colleagues and concluded that the gender, race, and political affiliation of a judge can predict her level of influence.

Nevertheless, there is no clear prediction as to when published opinions from one court of appeals will be cited in an opinion from another court of appeals. This chapter argues that institutional differences and individual-level characteristics of judges across courts influence the transmission of precedents and can be used to formulate such predictions.

Institutions, Judge Characteristics, and Predicted Citation Behavior

The court of appeals in each judicial circuit operates under its own set of local procedural rules. I consider the differences in publishing rules to be one of the most critical procedures for predicting the transmission of precedent. These rules determine whether an opinion is published and has precedential value. To use this variable, I must classify each circuit by its publishing rules. The least ambiguous publication rule was used to classify the courts—this rule outlines the number of judges from a panel needed to agree in order for the majority opinion to be published. In some courts, the rule states that the three-member panel must unanimously agree to the publication of the opinion. In other courts, the rule states that only the judge who authors the opinion faces the decision to publish her opinion. The type of publication rule for each court of appeals is shown in table 1.

| Circuit | Rule | Circuit | Rule | Circuit | Rule |

| 1st | Unanimous | 5th | Unanimous | 9th | Author-Only |

| 2nd | Author-Only | 6th | Author-Only | 10th | Unanimous |

| 3rd | Unanimous | 7th | Unanimous | 11th | Unanimous |

| 4th | Author-Only | 8th | Unanimous | DC | Unanimous |

Four of the twelve courts of appeals operate under the author-only publication rule, which leaves two-thirds of the courts operating under the unanimous-agreement publication rule. There is no apparent geographic or political reason for this variation.

There are many opinion-writing strategies a judge may take on while operating under the unanimous-agreement publication rule. One strategy the authoring judge can adopt is devising a well-researched and well-written initial draft that potentially can shield her opinion from criticism and veto threats from the two other panel members (Hume 2009). Another strategy available for the authoring judge is to seek out amendments from the other panel members and incorporate this additional language into her opinion. I expect that the unanimous-agreement rule places institutional constraints on the judge who is authoring the majority coalition’s opinion. In turn, the judge will author a high-quality opinion. High-quality opinions are not cheap to produce, as they are generally longer and well researched and contain many citations. A judge and her clerks must devote more time and more resources when crafting a high-quality opinion.

In turn, the different publication rules are expected to influence the broader network of precedents transmitting across the courts. When judges are researching precedents to cite in their own opinion, they will most likely prefer to cite precedents that are likewise grounded in research and add to the credibility of their opinions. For this reason, I expect precedents published by courts that have the unanimous-agreement publication rule will be transmitted through citations more frequently than precedents published by courts with the author-only publication rule.

I also predict that judges who share similar backgrounds, such as their legal education, are more likely to cite each other’s opinions. Those who have received similar legal training are expected to be more receptive and therefore more likely to cite the others’ opinions. Other immutable characteristics, such as the race and gender of judges, may also influence their citation behaviors. Likewise, judges with similar partisanship are expected to be more likely to cite each other’s opinions because the judges will share similar views about legal issues. Prior research in judicial politics has demonstrated that partisan ideology is one of the most influential predictors for explaining judicial behavior (Segal and Spaeth 2008); however, ideology does not explain all judicial behavior (Epstein and Knight 2013).

Data and Network Methodology

An original data set of over 300,000 majority opinions published by the US Courts of Appeals between 1970 and 2010 was developed in order to explore citation patterns and the transmission of precedent. The author, date of publication, and all citations were parsed from the text of each opinion. Citations were limited to opinions listed in either the Second or Third Series Federal Reporter. Further, citations to precedents that originated in the same court of appeals as the opinion were not included in the citation analysis. Altogether, there were 575,224 citations available to study.

Next, a series of variables related to features of the judge who authored the citing opinion and the judge who authored the cited opinion were developed using biographical data from the Federal Judicial Center (FJC). The law school attended by each judge was identified as either an elite law school or not; this allows us to observe whether a judge’s legal education impacts his opinion-writing behavior. Two binary variables, citing judge elite law and cited judge elite law, were created. Next, the race and gender of the citing judge and cited judge were identified. If the two judges shared the same gender, the variable same gender was valued at 1 and was otherwise valued at 0. If the two judges shared the same race, the variable same race was valued at 1 and was otherwise 0. Within the citation data set, the citing and cited judges were the same gender 82.3 percent of the time and were the same race 85.1 percent of the time. These judge-level characteristic variables likely have high values, since diversity in the form of race and gender was largely missing from the federal judiciary up until the 1980s.

Network Methodology

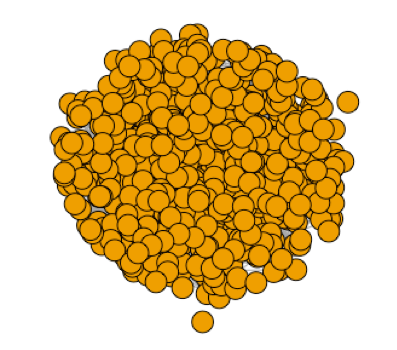

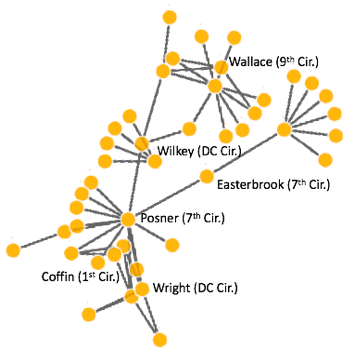

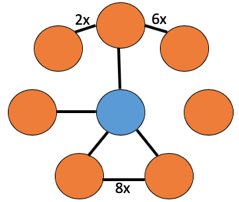

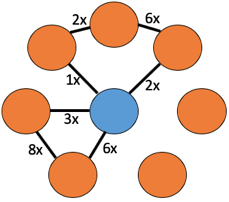

A network is a group or system of interconnected people or things. When people think of networks, they often think of social media—who follows whom online. By analyzing these connections, we can gain more nuanced insights into relationships among connected people. In this chapter, I study how judges are connected to other judges through citations to precedents. If a judge cites an opinion authored by another judge, they are connected in the legal network. Figure 2 depicts the legal network in this study. Each judge in the legal network is a node in the network, and each judge is represented with a circle. The citation from one judge to another is referred to as the edge in the network and is represented with a line that connects two circles. Figure 2A presents a network of judges citing each other’s opinions. Figure 2B zooms in to a specific part of figure 2A to highlight and identify some of the most connected judges in the network.

There are many reasons to believe that the reputation of a judge will impact how other judges cite her opinions. As one judge’s opinions are cited more frequently, other judges can observe this citation trend and, in turn, begin also citing opinions authored by the judge. For this reason, we need to account for how central each judge’s opinions are within the citation network. Observing whose opinions are being cited by whom will give us a great deal of insight into the transmission of precedents. Harris (1979) and other scholars have argued that the degree to which other judges cite a precedent is the single best indicator of how influential a precedent is and how influential the judge who authored the precedent is. Based on this logic, three network centrality measures were calculated to account for the reputation of each judge in the legal network.

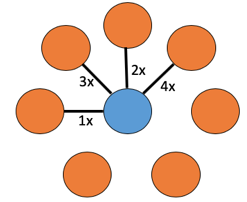

The first network measure is strength; this is a measure of the number of citations a judge has received and accounts for the total number of other judges who are issuing those citations. The next network measure is centrality, which essentially measures how often a judge is cited by other highly cited judges in the network. The final network measure is known as authority; here judges are given a higher authority score if they are frequently cited by judges that are also very well cited. Figure 3 depicts examples of each of the network measures calculated in the citation network. Note that judges are represented as nodes (circles) in the network, and citations between two judges are represented as edges (lines). The number of citations between two judges is also indicated in the visualizations. Each example in figure 3 depicts how a network measure for one judge, highlighted in blue, is conceptualized.

While the three network measures all relate to a cited judges’ reputation in the legal citation network, each is estimated differently. It is important to note that all three network measures are positively correlated. This positive correlation implies that when we observe one network centrality measure increasing, we can expect the other two measures will also increase in value. In turn, the network methodology has provided us with important variables for modeling citation behavior. Without these variables, the statistical test in the following section would likely suffer from omitted variable bias.

Results

In order to understand how judge-level attributes impact the transmission of precedents across the courts of appeals, the data are structured so that the unit of analysis is the number of times one judge (Ji) cites another judge (Jj) for each year (Ti). This procedure resulted in 7,868,474 observations and provided us with a count dependent variable that ranged from 0 to 38. The most common transmission pattern observed was judges from the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit citing precedents published by the Second Circuit. Female judges from the Court of Appeals in the Ninth Circuit are the most frequently cited female judges within the citation network.

Given that the dependent variable is a count of the number of times one judge cites another judge’s opinions in a year, a negative binomial regression is estimated. When a dependent variable is a count variable, a Poisson regression model is also an option; however, a Poisson regression model is not an appropriate choice here because the variance of the dependent variable, the count of citations, is greater than its mean. When the variance of a count variable is greater than the mean, it is a sign that the variable is overdispersed. If a Poisson model were to be employed with an overdispersed dependent variable, we would observe consistent but inefficient estimates along with downwardly biased standard errors (Long 2011). In other words, we could not trust the results of the analysis. For this reason, a negative binomial regression model was implemented, since it accounts for overdispersion by allowing “the conditional variance of y to exceed its conditional mean” (Long 2011, 230). Or to be blunt, this model fits the data better and produces more reliable results.

Given that the data capture forty years (1970–2010), fixed effects for each year and circuit were included in the analysis to control for unobserved heterogeneity in the courts (Beck and Katz 1995). This method is employed to make the results reliable and ensure the model best fits the data. Table 2 presents the estimated results. The percent change column represents how the number of citations is expected to change when there is a one-unit increase in a covariate or variable in the model while holding all other covariates constant. For example, if a dyad of judges changes from being different races to being the same race, we expect the number of citations to increase by 38.4 percent.

| Number of Citations | Percent Change | |

| Unanimous Agreement Publication Rule:

Citing Court of Appeals

Cited Court of Appeals

|

0.076** (0.004) 0.092*** (0.004) |

7.9%

9.6%

|

| Judge Characteristics:

Same Gender

Same Race

Same Political Party

Citing Judge Elite Law School

Cited Judge Elite Law School

|

-0.731 (2.908) 0.325*** (0.064) 0.012 (0.002) 0.032** ( 0.002) 0.059*** (0.000) |

-107.7%

38.4%

1.2%

3.2%

6.1% |

| Network Measures:

Cited Judge Strength

Cited Judge Centrality

Cited Judge Authority Intercept

|

-2.277 (6.1554) -1.364 (6.556) 0.424)** (0.050) 1.001*** (0.000) |

-874.7%

291.1%

52.8%

|

| N

Year Fixed Effects |

7,868,474

YES |

|

Note: *p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01d

The results concerning the publication rule in each circuit confirm prior expectations. When a judge is on a court that has the unanimous-agreement publication rule, their opinions are cited at a higher rate than judges from courts that have the author-only publication rule. Likewise, judges from courts with the unanimous-agreement publication rule are more likely to cite others—almost 8 percent more opinions from other circuits than judges from courts with the author-only publication rule. Substantively, judges from courts of appeals with the unanimous-agreement publication rule (found in the First, Third, Fifth, Seventh, Eighth, Tenth, Eleventh, and DC Circuits) are more likely to cite precedents that were established in other judicial circuits and are more likely to have their own precedents cited by judges in other judicial circuits. This result implies that the rules that dictate how an opinion is published have long-term implications for how other judges in the future might cite the opinion.

With regards to judge characteristics, the results indicate that when the citing judge and the cited judge share the same partisanship, the number of citations between these judges is expected to increase by 1.2 percent while holding the other covariates in the model constant. This finding suggests that judges who share the same partisan ideology are more likely to cite each other than judges with different partisan ideologies. Likewise, if the citing and cited judges are the same race, we are more likely to observe them citing each other than if the two judges were of different races. The results related to the gender of the citing and cited judges are not statistically significant, and thus this analysis cannot confirm whether there is a meaningful statistical relationship between the gender of a judge and how other judges cite her opinions. The findings in table 2 also suggest that if a judge attended an elite law school, she is cited more frequently by judges from other circuits as compared to judges who did not attend an elite law school. Likewise, judges who attended an elite law school are observed to cite about 3 percent more opinions from other circuits as compared to judges who did not attend an elite law school.

Only one of the three network measures was estimated to have a statistically significant relationship with the number of citations observed between two judges. The results indicate that as the cited judge’s authority within the network increases, we should expect to observe more citations to the opinion they author. Given that the authority score of judges in the network is based on how well connected one judge is to other frequently cited judges, it suggests that as a judge becomes more central and more popular with judges who are already popular, we are more likely to observe judges from other circuits citing her opinions. Interestingly, the authority network measure incorporates more information from the citation network as compared to the two other network measures (see figure 3).

Altogether, the results in table 2 have important implications for the transmission of precedents across courts of appeals. First, table 2 found a statistically significant relationship between the publication rule in the citing and cited judges’ courts and the number of citations connecting these judges. Other internal rules within each court of appeals may need to be studied in the future in order to fully unpack the relationship between these rules and the decision to import a precedent from another circuit. The results in table 2 also uncovered important nuances of judge-level characteristics, such as race and legal education. Up until the mid-1980s, most of the federal bench was composed of white male judges; it will be interesting to observe how the relationship between judge characteristics and citation behavior is impacted as the federal bench becomes more diverse. Finally, the results lead us to think about the role of reputations among judges and how a network of judicial relationships may impact law.

Conclusion

There is very little prior research concerning how variations in the publishing rules within a court of appeals’ local rules may impact the transmission of its precedents. Procedural rules have been extensively studied on the Supreme Court and shown to affect the decisions produced and how opinions are written. From the importance of opinion assignment (Maltzman and Walhbeck 1996; 2005; Lax and Cameron 2007; Segal and Spaeth 2002) to the voting rules in conference (Calderia, Wright, and Zorn 1999; Epstein, Landes, and Posner 2013), it is surprising that this area of research has yet to spill over to other, very salient, appellate courts.

This chapter found that institutional features do impact the citation network, the transmission of precedents across courts, and by implication, prestige. Further, individual-level characteristics of judges, such as race and legal education, were also shown to impact the transmission of precedents. Future research may also want to explore how judge characteristics impact the transmission of precedents within a court of appeals over time. This type of research question would have important implications for understanding the longevity of precedents.

The courts of appeals resolve many important legal questions each year. As the docket of the Supreme Court continues to shrink, the finality of decisions and the legal resolutions produced by each US Court of Appeals is expected to grow. As this trend continues, it becomes more important to understand the behaviors and development of precedent in the courts of appeals.

References

Aldisert, Ruggero J., 1989. “Precedent: What It Is and What It Isn’t: When Do We Kiss It and When Do We Kill It.” Pepperdine Law Review 17:605. (↵ Return)

Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan N. Katz. 1995. “What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data.” American Political Science Review 89 (3): 634–47. (↵ Return)

Benesh, Sara C., and Malia Reddick. 2002. “Overruled: An event history analysis of lower court reaction to Supreme Court alteration of precedent.” Journal of Politics 64(2): 534–50. (↵ Return)

Caldeira, Gregory A., 1985. “The Transmission of Legal Precedent: A Study of State Supreme Courts.” American Political Science Review 79: 178–94. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Caldeira, Gregory A., John R. Wright, and Christopher JW Zorn. 1999. “Sophisticated Voting And Gate-Keeping In The Supreme Court.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 15 (3): 549–72. (↵ Return)

Caminker, Evan H., 1994. “Why Must Inferior Courts Obey Superior Court Precedents?” Stan. L. Rev. 46 (817): 823–25. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4)

Canon, Bradley C., and Lawrence Baum. 1981. “Patterns Of Adoption Of Tort Law Innovations: An Application Of Diffusion Theory To Judicial Doctrines.” American Political Science Review 75 (4): 975–87. (↵ Return)

Cross, Frank. 2007. Decision Making in the U.S. Courts of Appeals. Stanford University Press. (↵ Return)

Epstein, Lee and Jack Knight. 1998. The Choices Judges Make. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly. (↵ Return)

———2013. “Reconsidering Judicial Preferences.” Annual Review of Political Science 16. (↵ Return)

Epstein, Lee, William M. Landes, and Richard A. Posner. 2013. The Behavior of Federal Judges: a Theoretical and Empirical Study of Rational Choice. Harvard University Press. (↵ Return)

Fowler, James H., and Sangick Jeon. 2008. “The authority of Supreme Court precedent.” Social Networks 30 (1): 16–30. (↵ Return)

Hinkle, Rachel K. 2017. “Panel Effects and Opinion Crafting in the US Courts of Appeals.” Journal of Law and Courts 5 (2): 313–36. (↵ Return)

———2015. “Legal constraint in the US Courts of Appeals.” The Journal of Politics 77 (3): 721–35.

Hume, R. J. 2009. “Courting multiple audiences: The strategic selection of legal groundings by judges on the US courts of appeals.” Justice System Journal 30 (1): 14–33. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Klein, D. E. 2002. Making law in the United States Courts of Appeals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return)

Kozel, R. J. 2012. “Precedent and Reliance.” Emory LJ. 62: 1459. (↵ Return)

Landes, William M., Lawrence Lessig, and Michael E. Solimine. 1998. “Judicial Influence: A Citation Analysis Of Federal Courts Of Appeals Judges.” The Journal of Legal Studies 27 (2): 271–32. (↵ Return)

Landes, William M., and Richared A. Posner. 1976. “Legal Precedent: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Law & Economics 19: 249. (↵ Return)

Lax, Jeffrey R., and Charles M. Cameron. 2007. “Bargaining and opinion assignment on the US Supreme Court.” The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 23 (2): 276–02. (↵ Return)

Lee, T. R., 1999. “Stare Decisis in Historical Perspective: From the Founding Era to the Rehnquist Court.” Vand. L. Rev. 52 (647). (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Long, J. Scott. 2011. Regression Models For Categorical And Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Maltzman, Forrest, and Paul J. Wahlbeck. 1996. “Strategic Policy Considerations And Voting Fluidity On The Burger Court.” American Political Science Review 90 (3): 581–92. (↵ Return)

———2005. “Opinion assignment on the Rehnquist court.” Judicature 89: 121. (↵ Return)

Rasmusen, E. 1994. “Judicial Legitimacy As A Repeated Game.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 10 (1): 63–83. (↵ Return)

Segal, Jeffrey Allan, and Harold J Spaeth. 2008. The Supreme Court And The Attitudinal Model Revisited. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return)

Solberg, Rorie Spill, Jolly A. Emrey, and Susan B. Haire. 2006. “Inter-Court Dynamics And The Development Of Legal Policy: Citation Patterns In The Decisions Of The U.S. Courts Of Appeals.” Policy Studies Journal 34 (2): 277–93. (↵ Return)

Songer, Donald R., Jeffrey A. Segal, and Charles M. Cameron. 1994. “The Hierarchy Of Justice: Testing A Principal-Agent Model Of Supreme Court-Circuit Court Interactions.” American Journal of Political Science 38 (3): 673. (↵ Return)

Songer, Donald R., and Reginald S. Sheehan. 1990. “Supreme Court Impact On Compliance And Outcomes: Miranda And New York Times In The United States Courts Of Appeals.” The Western Political Quarterly 43 (2): 297. (↵ Return)

Walker, Jack L. 1969. “The Diffusion Of Innovations Among The American States.” American Political Science Review 63 (3): 880–99. (↵ Return)

Westerland, Chad et al. 2010. “Strategic Defiance And Compliance In The U.S. Courts Of Appeals.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (4): 891–905. (↵ Return)

Class Activity

R is a powerful open source program for statistics and graphics. RStudio is an integrated development environment (IDE) for R. It is essentially a nice front-end for R. Rstudio provides a console, a scripting window, a graphics window, and an R workspace.

For information on installing R and Rstudio in Windows or in Mac OS X please see one of the following links:

- https://www.andrewheiss.com/blog/2012/04/17/install-r-rstudio-r-commander-windows-osx/

- https://owi.usgs.gov/R/training-curriculum/installr/

- https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/R-admin.html

Once R and Rstudio is installed on your computer, please open the .R file for in class exercise in Rstudio. Please note that the R file and accompanying data files should be saved in the same folder on your computer.

You will need to set the working directory of your Rstudio session to the folder where the script and data is saved. From Rstudio, use the menu to change your working directory under Session > Set Working Directory > Choose Directory.

Once the working directory is set, you can click and highlight sections of the code in the scripting window and click the ‘run’ button in the top left section of the window.