Chapter 1: Actors in the Judicial Process

1.4 Women of SCOTUS: An Analysis of the Different Voice Debate

Jeanine E. Kraybill

A Different Voice

As more women in the 1980s and 1990s attained judicial positions on federal and state courts, some social scientists and feminist scholars began to question if female judicial officers would adjudicate differently than their male counterparts (Kenney 2013). This potential difference spurs a series of important research questions whose answers provide valuable insight into judicial decision-making. For example, would gender diversity on the bench lead to differences in case outcomes, legal reasoning, and the judicial decision-making process? Drawing on the work of Carol Gilligan (1982), would women judges rule in a different voice than their male counterparts? Would women judges employ an ethics of care, prioritizing social relationships and context? Would male judges use more of an ethics of justice, focusing on competing rights, choice, and individual autonomy? Or would there be little difference between male and female judges because they operate under principles of judicial independence and impartiality and employ well-established legal norms (Hunter 2015)?

These unsettled questions continue to be examined by scholars via interviews, case rulings, and outcomes, with much attention given to the lower levels of federal and state courts, where diversity is increasing at a faster clip and there are larger number of judges overall, leaving the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) in need of further exploration. Therefore, I raise the question of whether there is evidence of Gilligan’s (1982) different voice among the women of SCOTUS and if their “voice” in legal opinions varies from their male counterparts. In particular, do female justices employ particular language characteristics associated with the ethics of care and the ethics of justice, as suggested by Gilligan (1982)? While ideally, all SCOTUS cases would be examined, this is beyond the scope of this study. Therefore, I focus on cases where issues relating to gender matter and/or may be a factor and where a different voice is most likely to manifest. To that end, this study centers on court opinions pertaining to gender, health care, LGBTQ+ issues, and religious liberty over the course of thirty-six years, beginning with the October term 1981 (and the appointment of the first female justice) through October term 2017, using a computer-assisted text analysis (CATA) program called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). The findings from this study suggest some evidence of the different voice debate on the Supreme Court—but not necessarily in the expected direction. Overall, this research provides more insight into the different voice debate at the highest level of power and justice and finds that the parameters of the debate as spelled out by Gilligan (1982) do not seem to apply to the High Court.

Issues of Gender and Justice

Symbolic Influence and the Judiciary

Some advocates for an increase in the number of female jurists center their arguments on the power of symbolism. For example, Kenney (2013) argues that the presence of women judges fosters a sense of democratic legitimacy in legal institutions because by including women, the courts are more representative of the wider fabric of society and the populations they serve. Similarly, Hunter (2015) argues that women should be represented in equal numbers on the bench, as this would better reflect their portion in terms of the general population and also among law school graduates. George and Yoon (2018) argue that judges’ backgrounds not only have important internal implications for the inner workings of the courts but also impact external perceptions of legal institutions. George and Yoon pay particular attention to this dynamic at the state court level, since these courts hear over 90 percent of all court cases. They refer to this symbolic underrepresentation as the “gavel gap,” which is measured by the proportional difference between the number of women and minorities serving as judges and the number of women and minorities in the general population. These scholars argue that as a way to cultivate trust and legitimacy in the courts and legal system, judges must be more demographically representative in terms of gender, race, and ethnicity.

Additionally, Kenney (2013) argues that an increase of female judges signals a sense of equal opportunity for women lawyers who are looking to become judicial officers, demonstrating the process of becoming a judge is what it purports to be: merit based, nondiscriminatory, and impartial. The law, like many institutions, has been designed by men and has worked to promote a male leadership and mentorship model. Therefore, having more female judges not only provides a sense of encouragement to other women who aspire to become lawyers and judges but facilitates mentorship between and among women already serving on the bench. Moreover, an increased presence of women judges can build mentorship opportunities with female law students as well as younger women and girls who are looking to become judges (Hunter 2015).

In addition to the symbolic arguments advocating for more female judges, scholars also argue for increased representation on practical grounds. For example, some argue that women judges may have a heightened empathy for female litigants, witnesses, and victims; therefore, they cultivate a more positive courtroom experience for them. Moreover, women judges may bring a sense of “gendered sensibility” to judicial decision-making by considering their unique perspectives as women and mothers, balancing work and family responsibilities, and dealing with various forms of sexism and discrimination (Hunter 2015; Hale and Hunter 2008). Gendered sensibility is also in line with feminist standpoint theory (FST), which Martin, Reynolds, and Keith (2002) use to advocate for more women judges. Stemming from Marxism, FST is the idea that one’s social location and experience matter, and hence women as a minority are aware of how the world (or in this case, the law) can be structured to favor some groups and disfavor others, producing a female consciousness in some judicial officers. This is also in line with Gilligan’s (1982) different voice argument, as she emphasizes that an ethics of care places a premium on relationships, stressing the importance of everyone having a voice.

Gender Differences and Judicial Outcomes

As women began to enter the judiciary in more appreciable numbers, scholars began to ask if their gender would impact their decision-making and if their presence would influence their male colleagues on the bench. Thus far, studies report mixed findings regarding if having women on the bench results in different judicial outcomes. For example, in looking at trial proceedings in urban areas, studies found differences in rulings between male and female judges (Gruhl, Sophn, and Welch 1981; Kritzer and Uhlman 1977). Yet at the federal level, Gottschall (1983) found little effect of gender among appellate judges, and Segal (2000) found that female Clinton appointees in district courts were less likely than their male counterparts to rule in favor of female plaintiffs making sexual discrimination claims. However, Peresie (2005) finds that the presence of women on three judge panels affects the collegial decision-making process and that male judges are more likely to find for the plaintiff when there is at least one female judge on the panel. And still other scholars find and argue that differences between male and female judges appear to be most pronounced in cases where gender is a salient factor, such as those involving discrimination and harassment (Allen and Wall 1987; Boyd, Epstein, and Mark 2010; Peresie 2005).

There are several factors that scholars argue may explain the mixed findings regarding gender differences and judicial outcomes. First, earlier work focused on a small sample of female judges that was not large enough to allow scholars to pick up differences between them and their male counterparts. Second, because female judges were once viewed as “novelties” or “tokens,” they felt pressure to rule in cases the way their male counterparts did (Davis 1986). This also speaks to the literature that argues that regardless of a judges’ background, he or she is superseded by long-standing norms of judicial behavior and reasoning and that exhibiting differences is inimical to the role of the judiciary; therefore, the law is impervious to a feminist judicial decision-making approach (Hunter 2015; Thornton 1996). Third, previous studies examined a range of issues, some of which did not include disputes where gender was a primary factor, which may have caused differences among male and female judges (Davis 1986; Walker and Barrow 1985). Fourth, former analyses did not include proper controls that may impact judicial outcomes, such as the ideology, previous careers, and experience of judges (Rhode 2001).

The Different Voice Debate

Beyond symbolism, it has been argued that more female judges will improve the judicial system by bringing a different voice to the bench and changing the position of women in the law more generally. Up until the 1990s, there had been little attempt to work through this argument. As previously noted, an unresolved debate has ensued on whether women make a qualitative difference in court case outcomes and if they rule from a different perspective then their male counterparts (Feenan 2008). In part, this debate gained more attention when Bertha Wilson, the first female justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, wrote her 1990 piece “Will Women Judges Really Make a Difference?” Wilson argues that if one holds to the tenants of judicial independence and impartiality, then the increased number of women judges should not make a difference. However, Wilson also calls attention to Carol Gilligan’s (1982) argument that women and men think differently about ethical and moral dilemmas and that women view themselves as connected to a community, whereas men see themselves as more autonomous. Wilson notes that Gilligan (1982) lays out the possibility that these differing perspectives may be a result of the childhood socialization process, arguing that female children are more attached to their mothers and hence prioritize relationships, whereas male children may be less connected and hence are defined through separation and individualism. Paralleling this to court cases, for women, it is not about winning or losing but about preserving relationships and developing an ethics of care that takes into account circumstance and context. Wilson (1990) argues that there is merit in the ethics of care perspective, as it helps explain the reluctance of courts (whose judicial officers are predominately male) to consider the circumstances of cases along with the courts’ propensity to reduce disputes to their essential components and rules. Here, Wilson emphasizes Gilligan’s ethics of justice perspective, which argues that men see moral dilemmas as arising from competing rights, welcome the adversarial process, and view disputes in terms of winners and losers, whereas women are more likely to reconcile competing obligations and hence view cases in a broader context. Therefore, Wilson concludes that from their different perspectives, women judges have the potential to bring a “new humanity” to court decisions and can make a difference by viewing and ruling on cases in terms of a larger societal picture and impact.

In looking at gender as a variable in order to determine if women adjudicate differently than men, scholars have examined whether the judge being a feminist makes an impact, with some studies showing feminism among male and female jurists as an important factor (Martin, Reynolds, and Keith 2002). In looking at cases of paired men and women on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, Davis (1992) finds minimal evidence of gender differences. However, in another study, Songer, Davis, and Haire (1994) do find evidence of gender differences in sex discrimination cases, which is consistent with some of the research previously addressed. In looking at divorce cases, Martin and Pyle (2005) find that women judges were more supportive of female litigants. Moreover, when serving alongside one other female, male judges were also more supportive of women litigants.

Overall, the studies that examine gender differences among judges and their impact on court cases tend to focus on their outcomes and have yielded mixed results. To my knowledge, previous research has not examined the language style of court opinions in the specific context of the difference voice debate. In order to more effectively examine this difference, one must analyze the words and rhetorical style that male and female judges use. Moreover, the work noted above has not examined this debate among the women and men of the Supreme Court of the United States, adding a new avenue of research to explore if male and female judicial officers adjudicate in a different voice.

Research Questions and Expectations

Are women of the Supreme Court more likely to employ language in their opinions that is associated with an ethics of care and men with an ethics of justice? Most research on court opinions has focused on liberal or conservative ideological outcomes; however, Lupu and Fowler (2010) argue that the content of opinions is more important than the holding (decision) of the court case. Rhode and Spaeth (1976) note that it is not the ideological dimension of the opinion but the content of it that makes policy. Citations of Supreme Court opinions have also been analyzed in terms of positive and negative treatment, finding that once a particular case is positively cited, it gains vitality and tends to be cited more frequently in subsequent cases (Hansford and Spriggs 2006). As Cross and Pennebaker (2014) and Tiller and Cross (2006) note, in contrast to social and political scientists, legal scholars analyze the particular details of a case with little attention to the overall meaning of language in the opinion, and they do not employ statistical analysis to find relationships, patterns, or associations, which provide broader and more general understanding of the content of court opinions.

Therefore, the analysis I present in this chapter is poised to make a meaningful contribution to this unsettled debate by directly testing if men and women of the High Court employ different language styles and hence speak with a different voice. Overall, I expect that they do—that there will be differences in the language men and women of the High Court use in their opinions, with female justices of the Supreme Court employing language associated with an ethics of care and male justices using language that is more affiliated with an ethics of justice. For example, as previously noted, words associated with an ethics of care is more collective and contextual and prioritizes relationships, and some scholars in political and social science have suggested that this type of rhetoric can be associated with women legislators and leaders (Dodson and Carroll 1991; Kathlene 1994; Rosenthal 1998; Thomas 1997).

Examining the Language of Court Opinions

Since we need to look at the context of opinions, I use the CATA program LIWC, which examines language by reading and analyzing text for characteristics such as, but not limited to, emotion, tone, and affect. It consists of approximately ninety output variables and is designed with a preformulated dictionary composed of over six thousand words, word stems, and emoticons (LIWC 2015). The language and content of court opinions are at the core of what the law is and have an impact on both society and the legal system (Cross and Pennebaker 2015). For example, scholars argue that the formulation of an opinion is at the center of appellate adjudication and that what judges say can be even more consequential than how they vote, as a case’s legal reasoning can have a wide-ranging impact by altering legal policy and hence structuring the outcome of future disputes (Coffin 1994; Shapiro and Stone Sweet 2002; Hansford and Spriggs 2006). Overall, it is the rhetoric of judges that is persuasive in legal opinions, and it is the style of their language that can assist in understanding the court’s work; therefore, it is imperative that it be more systematically studied (Murphy 1964; Chemerinsky 2002).

Methodology

As briefly noted in the introduction, in order to conduct an analysis testing the different voice theory via Supreme Court opinions, I examine cases dealing with gender, health care, religious liberty, and LGBTQ+ issues from the 1981–82 session through the 2017–18 session. This is consistent with previous scholars who have analyzed differences of opinion between male and female justices using cases relating to gender—that is, cases where gender is more pronounced or a salient factor (Allen and Wall 1987; Boyd, Epstein, and Martin 2010; Peresie 2005). These four categories of cases are employed because issues of gender can and do get intertwined with these topics. The time period was chosen in order to include and analyze opinions across the four selected topics by women who have served on the US Supreme Court, with Sandra Day O’Connor being the first in 1981. In total, the sample consisted of 649 opinions (see table 1).[1]

| Category | Number of Cases | Number of Opinions | Number of Lead Female Authored Opinions | Number of Lead Male Authored Opinions | Number of Per Curiam Opinions |

| Gender | 35 | 90 | 24 | 64 | 2 |

| Health Care | 122 | 277 | 51 | 217 | 9 |

| LGBTQ+ | 12 | 34 | 1 | 30 | 3 |

| Religious Liberty | 73 | 248 | 46 | 200 | 2 |

| Total | 242 | 649 | 122 | 511 | 16 |

After gathering the descriptive data captured in table 1, all opinions were separated into individual Microsoft Word files and labeled by the lead author. Each file consisted only of the text of the opinion. Majority, dissenting, concurring, and per curiam opinions were analyzed.[2] For example, in the case of Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, 458 U.S. 718 (1982), Justice Harry Blackum’s dissent was stored in its own Word file and was cleared of any additional words, citations, or symbols that were not included in the actual text of the opinion, and Sandra Day O’Connor’s majority opinion on this case was handled the same way. This file preparation was done for easy upload into the LIWC program and so that only the text of each opinion was analyzed.

LIWC is equipped with word variables that help capture the frequency and percentage of certain words and related phrases. LIWC’s program analyzes over six thousand common words and word stems. LIWC is an appropriate tool to use to study court opinions, as they often employ ordinary language so that they are understood. Moreover, LIWC is one of the most common language tools used to study large bodies of text and has been used in previous research examining court decisions (Cross and Pennebaker 2015). Word variables in LIWC that were associated with the characteristics of an ethics of care and an ethics of justice were combined in order to create each respective category. For example, the category “ethics of care” was devised by combining the LIWC word variables social, family, friend, and we. The “ethics of justice” category was devised by combining the word variables power, achieve, and I.

Once the sample of court opinions were run through the LIWC program, t-tests were conducted to compare the use of language associated with the ethics of justice and ethics of care categories among the women of the Supreme Court in order to determine if they employed more of the latter. A t-test is a form of inferential statistics used to assess if there is a significant difference between the means (averages) of two different groups (Siegel 2018). This allows the researcher to make predictions from the data about the groups he or she is comparing. T-tests were also performed to see if the women varied in their use of either category when compared to the total number of male-authored opinions. When comparing the use of language associated with the ethics of care and the ethics of justice frameworks among and between only the women of the Supreme Court, Sandra Day O’Connor is used as the baseline. For example, in looking at the cases involving gender, t-tests were done to compare Sandra Day O’Connor versus Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sandra Day O’Connor versus Sonia Sotomayor, and Sandra Day O’Connor versus Elena Kagan across the various case types. Since O’Connor was the first woman to serve on the High Court and has been arguably the most critical of the different voice debate among the four female justices examined, she is the logical candidate to serve as the baseline female justice.

Findings

The study yields interesting results and shows that men and women of the Supreme Court can employ a different voice. However, the findings run counter to expectations and Gilligan’s (1982), as they demonstrate that the female justices overall tend to employ more language associated with an ethics of justice and that the male justices utilize language that is more aligned with an ethics of care. Furthermore, there are times when Sandra Day O’Connor (who again referred to this debate as “dangerous and unanswerable”) employs more language associated with an ethics of care compared to her female counterparts. The discussion of the findings below highlights the key takeaways from this analysis.[3]

Male and Female Comparison across the Entire Sample

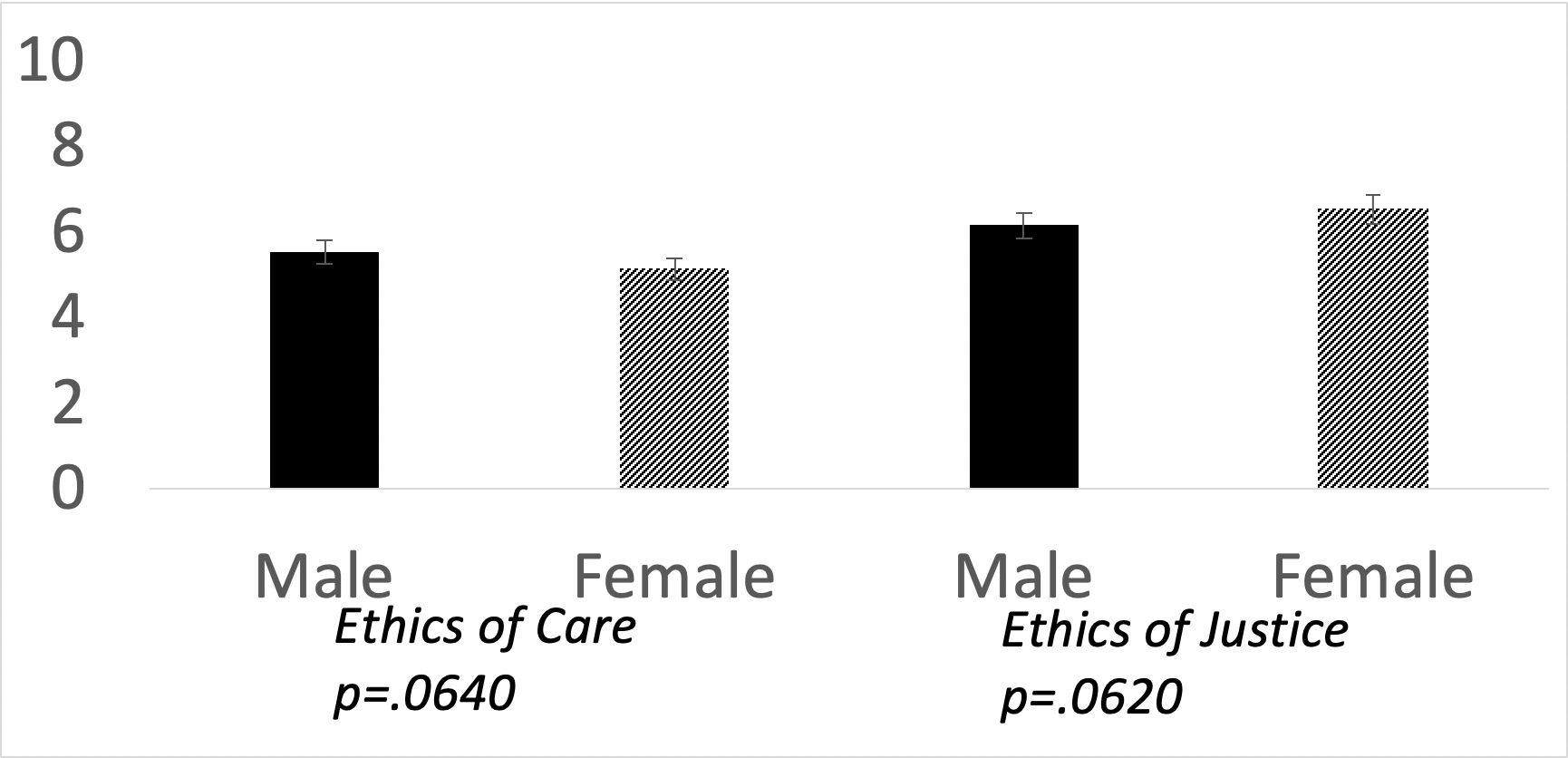

When looking at the entire sample of opinions across the four types of cases over the period analyzed, the results show that male justices of the Supreme Court significantly employed slightly more language associated with an ethics of care (5.53 percent to 5.13 percent), and the female justices significantly utilized slightly more language aligned with an ethics of justice (6.52 percent to 6.14 percent), which is not in line with expectations (see figure 1).

Gender

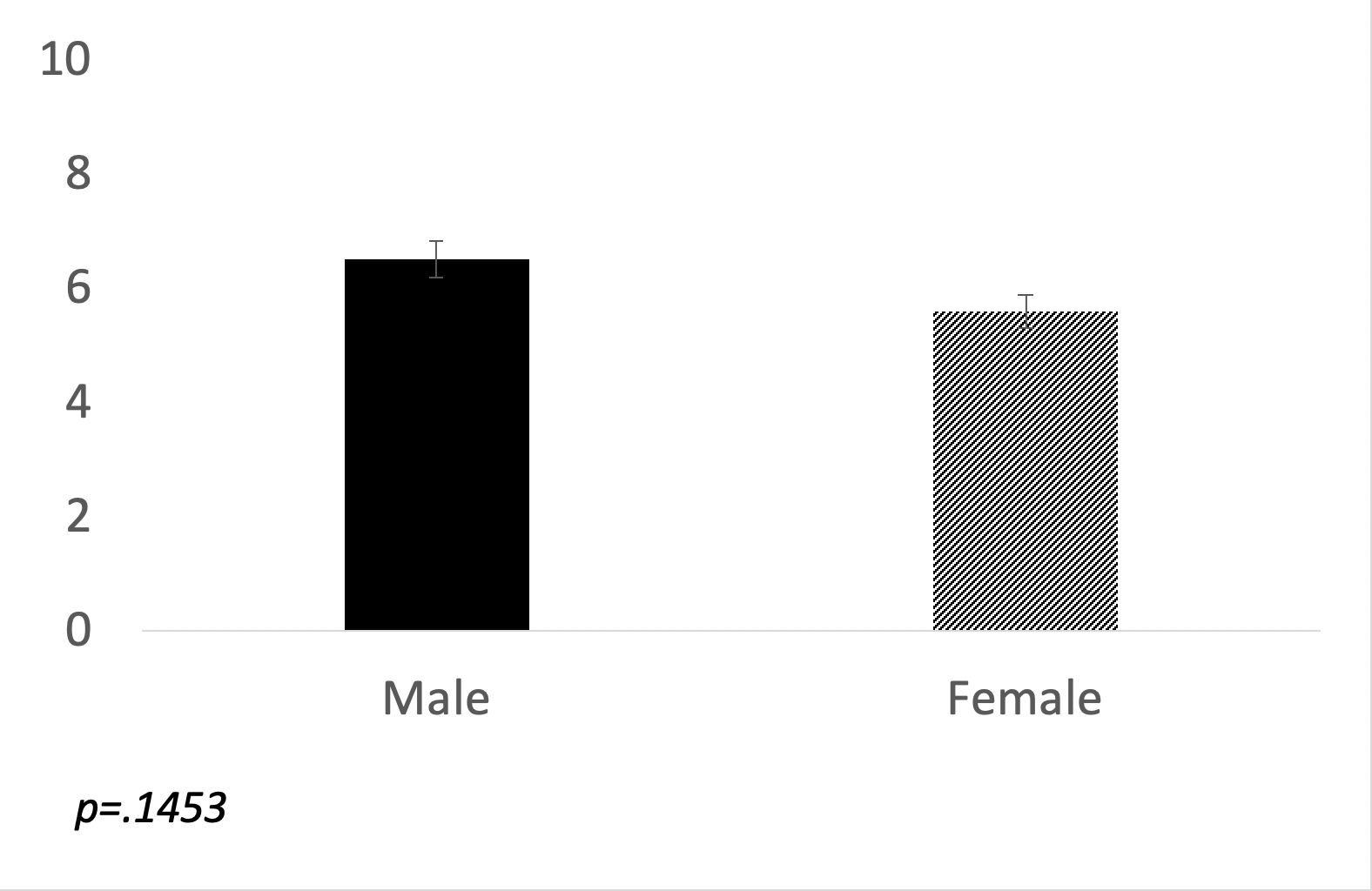

In looking at cases only involving gender, we see that the women of the High Court employed a slightly higher percentage of language associated with the ethics of justice category (focusing on individual rights) compared to the total group of male justices (6.58 percent to 6.42 percent, respectively); however, the results were not significant. Yet counter to expectations, when looking at language associated with the ethics of care category (placing a premium on relationships), the men of the Supreme Court used this language at a higher percentage than their female counterparts (6.49 percent to 5.58 percent, respectively), with a suggestive significance level of p = 0.1453 (see figure 2).

This trend can be seen in cases such as Tuan Anh Nguyen v. INS, 533 U.S. 53 (2001), which dealt with gender-based distinctions of parents to fulfill citizenship requirements of children born out of wedlock and abroad to a citizen father and noncitizen mother. The Court’s majority opinion, authored by Kennedy, focused not only on DNA proof to claim paternity of the father but also on the relationship between the male parent and child, arguing that making sure there was an opportunity for such a relationship helped further an important government interest. Kennedy argued, “To ensure that the child and the citizen parent have some demonstrated opportunity or potential to develop not just a relationship that is recognized as a formal matter, by law, but one that consists of the real, everyday ties that provide a connection between child and citizen parent” (Tuan Anh Nguyen v. INS, 533 U.S. 53 [2001]). The majority acknowledge that the DNA requirement was met by the father in this case, who was also the citizen parent. The opinion focused more on the relationship opportunity standard; citizen fathers must show that there was, at the very least, the opportunity for a parental bond between the citizen parent and the child. The lack of contact in this case allowed the Court to deny citizenship to the child. In her dissent (to which Ginsburg concurred), O’Connor argued that sex-based classifications impede on individual rights and “deny individuals opportunity” (Tuan Anh Nguyen v. INS, 533 U.S. 53 [2001]). In refuting the relationship opportunity standard, O’Connor argued that “children who have an opportunity for such a tie with a parent, of course, may never develop and actual relationship with that parent” (Tuan Anh Nguyen v. INS, 533 U.S. 53 [2001]). The language of O’Connor’s dissent is more consistent with the ethics of justice framework because it focuses on Tuan’s individual ability to seek citizenship on the basis of his father being a US citizen rather than on the opportunity for a father-son relationship to exist and develop between them. Overall, O’Connor argued that different requirements for children’s acquisition of citizenship depending on whether the citizen parent was a mother or father denied Tuan equal opportunity and protection.

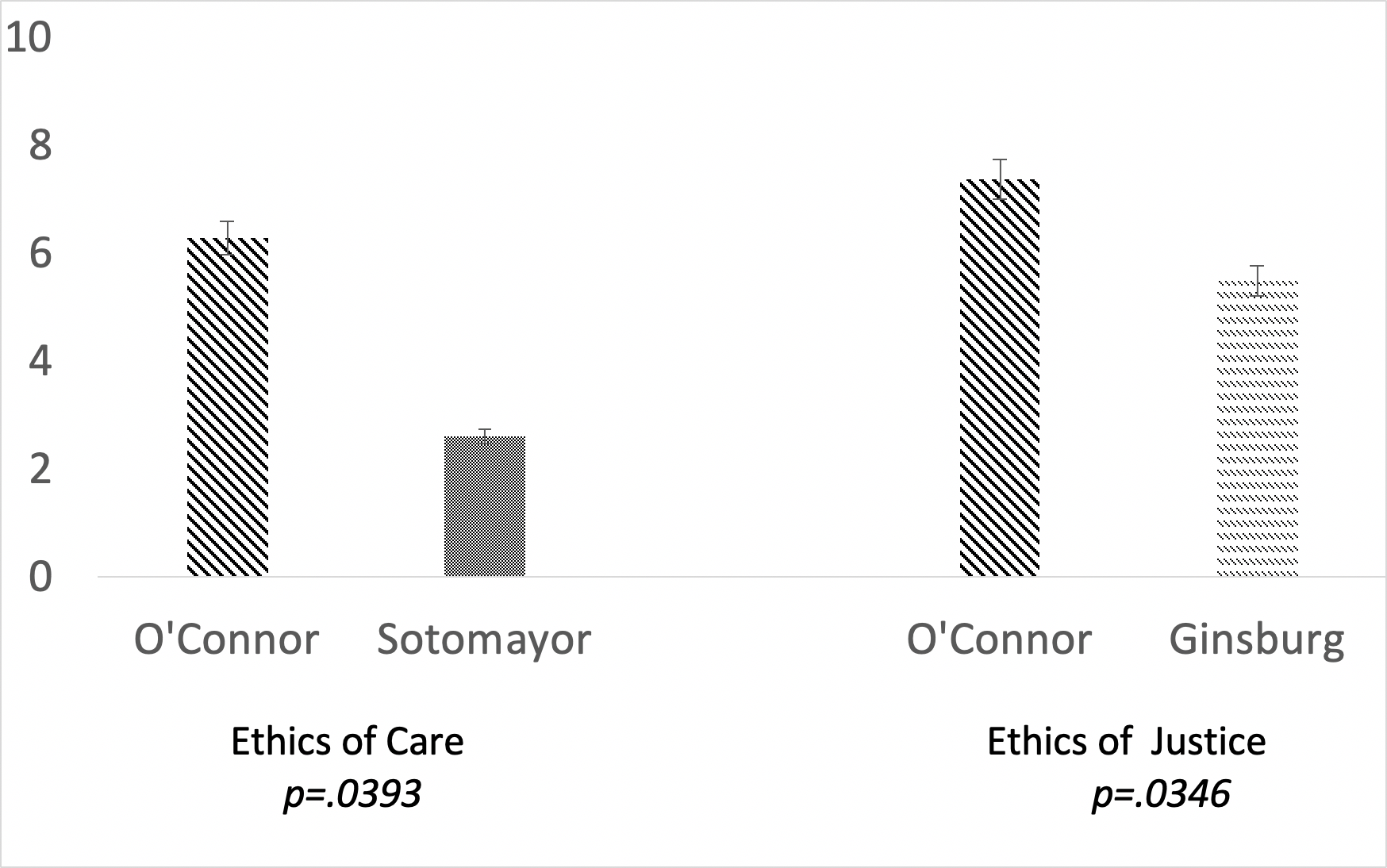

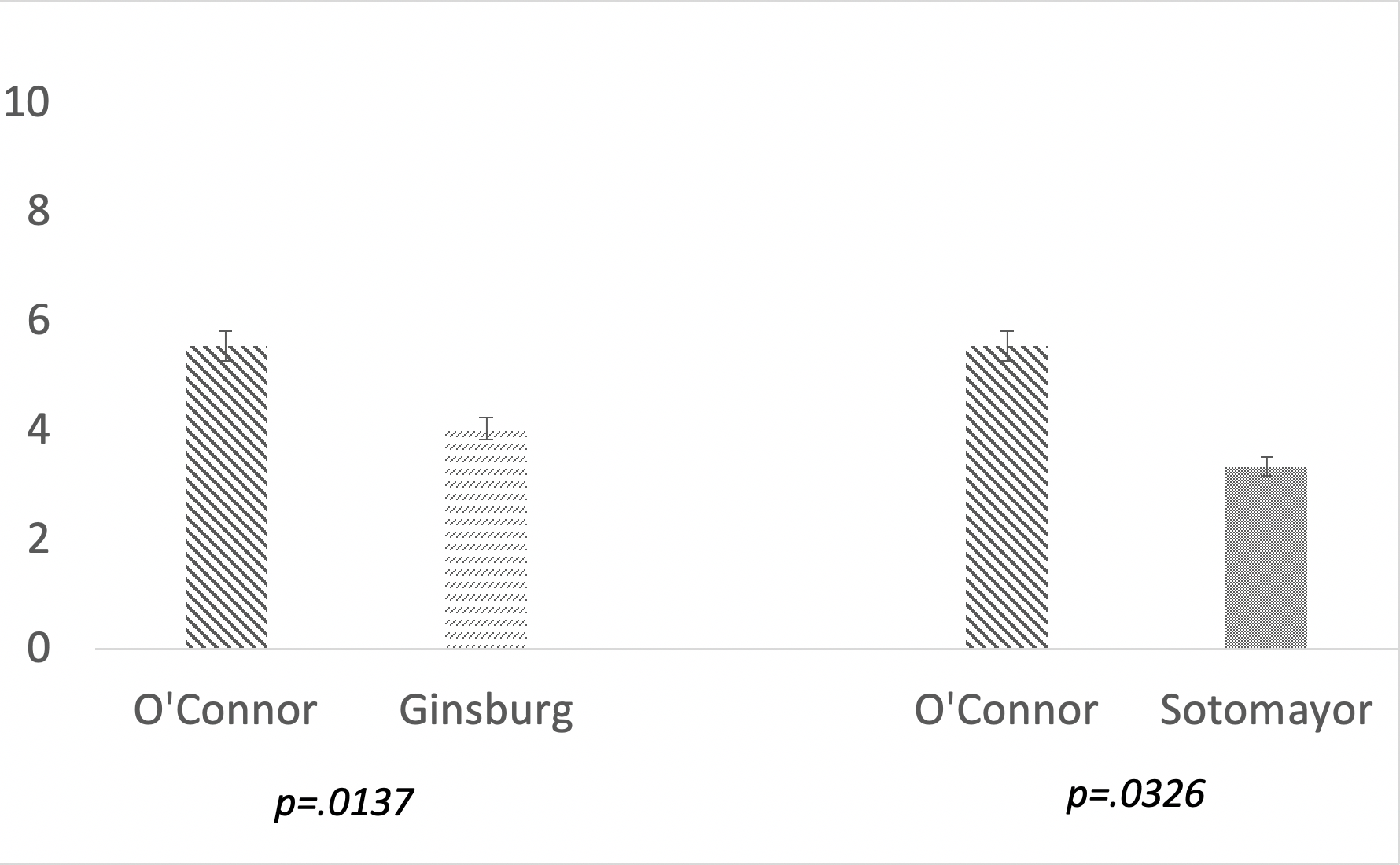

Now, in turning our attention specifically to the women of the Supreme Court and cases involving gender, I find that O’Connor was more likely to employ language associated with both an ethics of care and an ethics of justice compared to her female counterparts. For example, as figure 3 shows, when compared with Sonia Sotomayor, O’Connor significantly used more language associated with an ethics of care (6.28 percent compared to 2.6 percent).

Figure 3 also shows that O’Connor significantly employed more language associated with an ethics of justice than Ruth Bader Ginsburg (7.37 percent compared to 5.49 percent). These results are somewhat counter to expectations, as I argue that women of the Court (including O’Connor) would be more likely to employ language associated with an ethics of care. However, I found that O’Connor used both types of language more so than her female counterparts. In some ways, these findings echo back to O’Connor’s criticism of the different voice debate—that women are not a monolith. It may also signal that at times when dealing with issues of gender, O’Connor felt she could not differ from traditional norms of the Court, which have been established under male paradigms.

Health Care

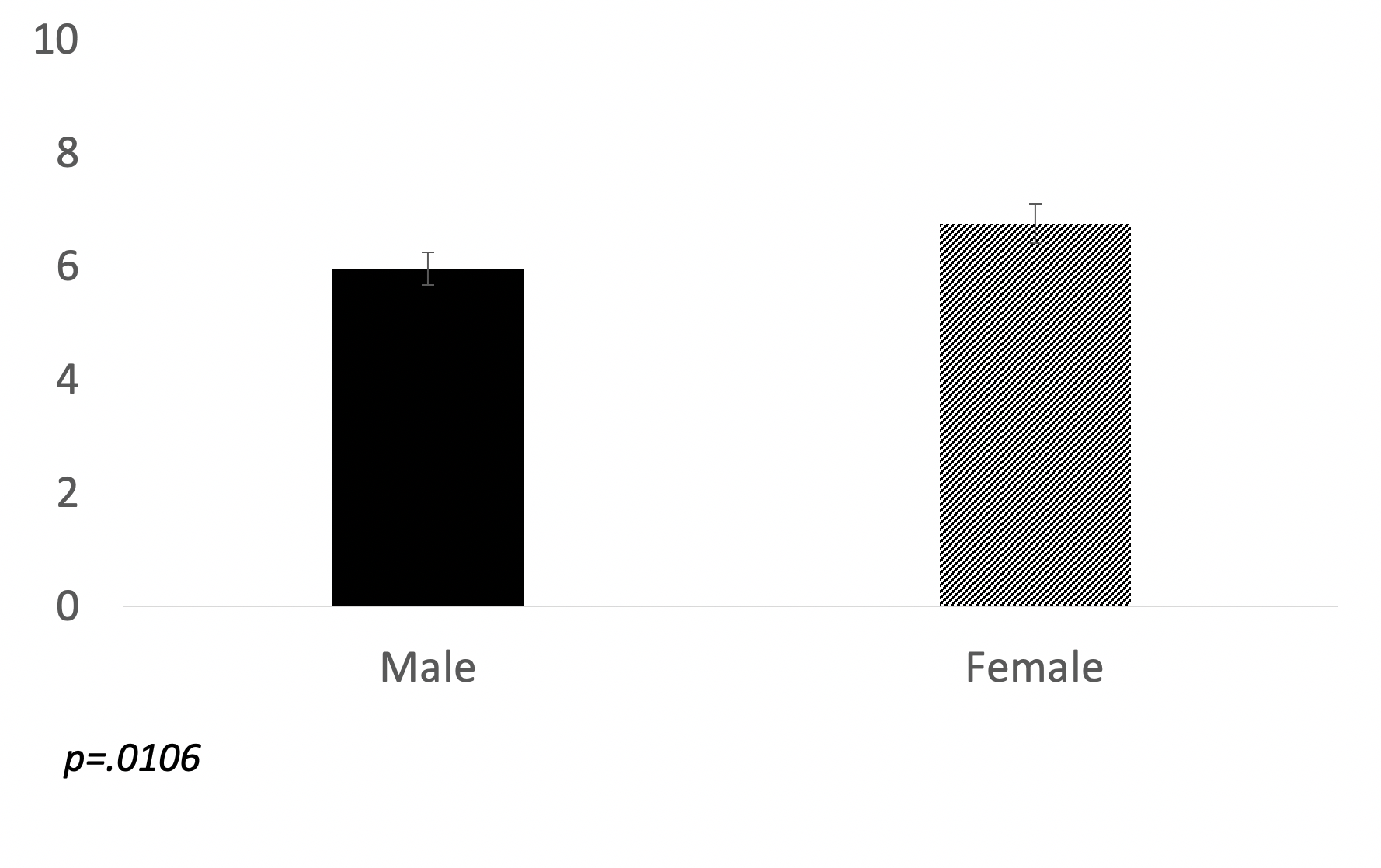

All male and female court opinions on cases involving health care were also compared via the ethics of care and ethics of justice categories. Similarly to the cases involving gender, the male justices of the Supreme Court employed more language associated with an ethics of care (5.19 percent compared to 4.72 percent, respectively), with a p-value of .1377, which is not highly significant but suggests a close probability for the use of this type of language. Involving these types of cases, the results also show that the women of the Supreme Court employed significantly more language associated with the ethics of justice framework than their male counterparts (6.76 percent to 5.97 percent, respectively; see figure 4).

This trend can be seen in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 83 (1992), which dealt with required health care procedures and provisions before a female could seek and obtain an abortion in the state. The provisions enacted by the state legislature required informed consent, a twenty-four-hour waiting period prior to the procedure, parental consent, clinic reporting procedures, and spousal consent. The Court agreed the first four regulations were constitutionally admissible but were divided on spousal consent, which was ultimately ruled to create an “undue burden” on a women’s right to terminate her pregnancy. Counter to expectations, Sandra Day O’Connor, who authored the Court’s decision, framed her opinion within the context of an ethics of justice by discussing women’s personal liberty and the health-related issue of reproductive rights, arguing for women’s autonomy in these decisions. In so doing, O’Connor stated,

Though abortion is conduct, it does not follow that the State is entitled to proscribe it in all instances. That is because the liberty of the woman is at stake in a sense unique to the human condition and so unique to the law. The mother who carries a child to full term is subject to anxieties, to physical constraints, to pain that only she must bear. That these sacrifices have from the beginning of the human race been endured by woman with a pride that ennobles her in the eyes of others and gives to the infant a bond of love cannot alone be grounds for the State to insist she make the sacrifice. Her suffering is too intimate and personal for the State to insist, without more, upon its own vision of the woman’s role, however dominant that vision has been in the course of our history and our culture. The destiny of the woman must be shaped to a large extent on her own conception of her spiritual imperatives and her place in society.

O’Connor’s reference to women’s “liberty” being at stake, her discussion of women in an individual context—emphasizing consequences that “only she must bear” with the realities of bringing a child to full term—her mention of women’s suffering as “personal,” and her assertion that women should have the ability to construct their “destiny” on their “own conception” are all associated with the concept of the ethics of justice framework.

On the other hand, in their dissent, William Rehnquist, Byron White, Antonin Scalia, and Clearance Thomas put a premium on the spousal relationship, which is more aligned with an ethics of care, arguing that the state had “legitimate interests” in protecting the “interests of the father and in protecting the potential life of the fetus . . . and promoting the integrity of the marital relationship.”

In looking at the women of the Supreme Court and their opinions on health care, the findings show that O’Connor employed more language associated with an ethics of care when compared to Ginsburg and Sotomayor (see figures 5). However, when compared to Kagan, O’Connor employed less language relating to an ethics of care (5.54 percent compared to 6.50 percent, respectively), though the results are not significant. When comparing the opinions on health care via the ethics of justice overall, O’Connor employed slightly less language associated with this concept compared to Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Kagan (6.51 percent compared to 7.08 percent, 6.6 percent, and 6.6 percent, respectively); however, none of the results were significant.

Religious Liberty

Regarding the results for the total of male- and female-authored opinions on religious liberty, there are negligible differences between the two groups regarding language associated with the ethics of care and ethics of justice categories. For example, the male justices employed 5.39 percent of language associated with an ethics of care and the women 5.37 percent. A similar pattern continues with an ethics of justice, with the men using 6.29 percent of this language in their opinions on religious liberty and the women 6.17 percent.

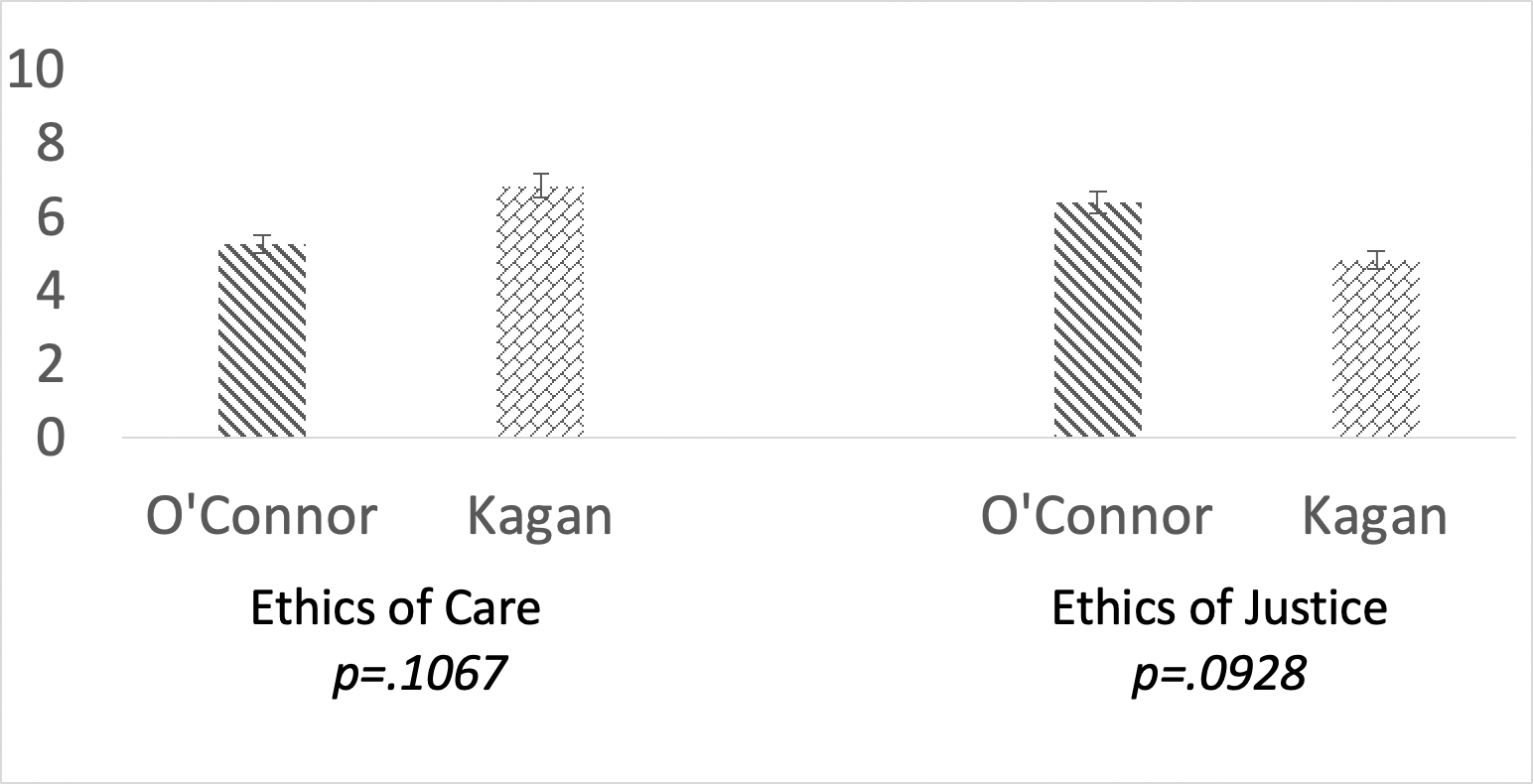

However, the results are a mixed bag across religious liberty opinions authored by the female justices of the Supreme Court. For example, O’Connor employed slightly less language associated with the ethics of care framework when compared to Ginsburg (5.27 percent to 5.85 percent, respectively), although the results are not significant. Yet O’Connor did employ more of this type of language compared to Sotomayor (5.27 percent to 4.21 percent, respectively), though again, the results are not significant. However, similarly to the findings on health care, Kagan employed more language associated with an ethics of care compared to O’Connor (6.86 percent to 5.27 percent, respectively), and the results are hovering around significance with a p-value of 0.1067. In looking at the results among the women of the Supreme Court regarding opinions on religious liberty and the use of language associated with an ethics of justice, O’Connor employed more of this language than any of her female counterparts (6.40 percent compared to 5.96 percent for Ginsburg and 6.11 percent for Sotomayor); however, this was only significant when examining the use of this language between O’Connor and Kagan (see figure 6).

Implications and Future Research

This analysis of gender-related cases and their opinions yields further insight into the different voice debate. First, the findings show that when looking at the women of the Supreme Court, they are not a monolith. Unlike what some of the political science scholarship noted above has found regarding women in legislative bodies, this study finds that there is not a particular language style the women of SCOTUS use—at least in terms of language associated more with women and men. For example, the findings in this analysis show that female justices do not uniformly rule using language associated with an ethics of care or ethics of justice. For instance, in opinions on gender and health care, Sandra Day O’Connor employed both styles of language and more so than Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor but not necessarily Elena Kagan. Although the women of the Supreme Court did not uniformly issue opinions associated with the ethics of care, we see that women among and between themselves can rule in a different voice.

The results also show interesting differences between the male- and female-authored opinions. For example, in cases on gender and health care, we see that the male justices in total tended to employ language associated more with an ethics of care and women with an ethics of justice. We see this same pattern when comparing the total amount of male- versus female-authored opinions across the entire sample. This pattern challenges Gilligan’s (1982) argument that the ethics of care perspective is more associated with women than men, giving further insight into the different voice debate. Some scholars may again chalk this up to women of the High Court conforming to the male norms of their profession or not wanting to appear to rule in a way that has been traditionally associated with women. Or in the cases relating to gender and health care, one may argue that the women employ more language associated with the ethics of justice category because of their feminist consciousness and are hence more likely to put a premium on women’s autonomous individual rights over women’s connections to their society, family, and so on. These potential explanations, though, do not address the findings regarding male justices and their use of language associated with an ethics of care. Regardless, the results show that women on the bench do employ language in their opinions that is not always consistent with an ethics of care and that there is diversity among women (at least on the High Court) in terms of the language style.

The next step in this type of study would be to more directly examine whether utilizing language associated with an ethics of care or ethics of justice adds to actual differences of opinion among and between the female justices and then among the male versus female justices. Surveying and/or interviewing judges to assess their positions on the different voice debate would help shed light on whether female and male judicial officers feel there is merit in this debate and how it may impact the courts and legal system overall.

References

Allen, David and Diane Wall. 1987. “The Behavior of Women State Supreme Court Justices: Are They Tokens or Outsiders?” Justice System Journal 12 (2): 232–245. Accessed November 24, 2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27976640 (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Boyd, Christina, Lee Epstein, and Andrew D. Martin. 2010. “Untangling the Causal Effects of Sex on Judging.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (2): 389–411. Accessed November 24, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00437.x (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Chemerinsky, Erwin. 2002. “The Rhetoric of Constitutional Law.” 100 Michigan Law Review: 2008–2035. Accessed December 24, 2018. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/713/ (↵ Return)

Coffin, Frank M. 1994. On Appeal: Courts, Lawyering, and Judging. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. (↵ Return)

Cross, Frank B. and James W. Pennebaker. 2015. “Language of the Roberts Court.” Michigan State Law Review 853–894. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Davis, Sue. 1986. “President Carter’s Selection Reforms and Judicial Policymaking: A Voting Analysis of the United States Courts of Appeals.” American Politics Research 14(4): 328–344. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X8601400404 (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Davis, Sue. 1992. “Do Women Judges Speak ‘In a Different Voice?’ Carol Gilligan, Feminist Theory, and the Ninth Circuit.” Wisconsin Women’s Law Journal 8 (1): 143–173. (↵ Return)

Dodson, Deborah L. and Susan J. Carroll. 1991. Reshaping the Agenda: Women in State Legislatures. New Brunswick, NJ: The State University of New Jersey Press. (↵ Return)

Feenan, Dermont. 2008. “Women Judges: Gendering Judging, Justifying Diversity.” Journal of Law and Society, 35 (4): 490–519. (↵ Return)

George, Tracey E. and Albert H. Yoon. 2018. “The Gavel Gap: Who Sits in Judgement on State Courts?” American Constitution Society for Law and Policy. Accessed November 21, 2018. http://gavelgap.org/pdf/gavel-gap-report.pdf (↵ Return)

Gilligan, Carol. 1982. In A Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6) (↵ Return 7) (↵ Return 8)

Gottschall, Jon. 1983. “Carter’s Judicial Appointments: The Influence of Affirmative Action and Merit Selection on Voting on the U.S. Courts of Appeals.” Judicature 67 (4): 165–173. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/judica67&div=42&id=&page= (↵ Return)

Gruhl, John, Cassia Sophn, and Susan Welch. 1981. “Women as Policymakers: The Case of Trial Judges.” American Journal of Political Science 25 (2): 308–322. Accessed November 24, 2018. doi: 10.2307/2110855 (↵ Return)

Hale, Brenda and Rosemary Hunter. 2008. “A Conversation with Baroness Hale.” Feminist Legal Studies 16: 237–248. Accessed November 21, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s10691-008-9090-5 (↵ Return)

Hansford, Thomas G. and James E. Spriggs II. 2006. The Politics of Precedent on the U.S. Supreme Court. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Hunter, Rosemary. 2015. “More than Just a Different Face? Judicial Diversity and Decision-making.” Current Legal Problems 68: 119–141. Accessed November 21, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/cuv001 (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5)

Kathlene, Lyn. 1994. “Power and Influence in State Legislative Policymaking. The Interaction of Gender and Position in Committee Hearing Debates.” American Political Science Review 88 (3): 560–576. doi: 10.2307/2944795 (↵ Return)

Kenney, Sally J. 2013. Gender & Justice: Why Women in the Judiciary Really Matter. New York, NY: Routledge. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Kritzer, Herbert M. and Thomas M. Uhlman. 1977. “Sisterhood in the Courtroom: Sex of Judge and Defendant as Factors in Criminal Case Disposition.” Social Science Journal 14 (2): 77–88. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://experts.umn.edu/en/publications/sisterhood-in-the-courtroom-sex-of-judge-and-defendant-as-factors (↵ Return)

Legal Information Institute. 2018. “Per Curiam Decision.” Cornell Law School. Accessed November 24, 2017. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/per_curiam (↵ Return)

Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). 2015. “The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC 2015. LIWC Manual. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/31333/LIWC2015_LanguageManual.pdf (↵ Return)

Lupu, Yonatan and James H. Fowler. 2010. “The Strategic Content Model of Supreme Court Opinion Writing.” Accessed December 24, 2018. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ef7d/87f0f44b07f1462f51216638828fe6b6fdea.pdf (↵ Return)

Martin, Elaine and Barry Pyle. 2005. “State High Courts and Divorce: The Impact of Judicial Gender.” University of Toledo Law Review 36 (4): 923–948. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Martin, Patricia Yancey, John R. Reynolds, and Shelley Keith. 2002. “Gender Bias and Feminist Consciousness among Judges and Attorneys: A Standpoint Theory of Analysis.” Signs 27 (3): 665–701. doi: 10.1086/337941 (↵ Return)

Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, 458 U.S. 718 (1982). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/458/718/

Murphy, Walter F. 1964. Elements of Judicial Strategy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Peresie, Jennifer L. 2005. “Female Judges Matter: Gender and Collegial Decision making in the Federal Appellate Courts.” The Yale Law Journal 114 (7): 1759–1790. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://www.yalelawjournal.org/note/female-judges-matter-gender-and-collegial-decisionmaking-in-the-federal-appellate-courts (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 121 S.Ct. 2791 (1992). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/505/833/

Rhode, David W. and Harold J. Spaeth. 1976. Supreme Court Decision Making. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co. (↵ Return)

Rhode, Deborah L. 2001. “The Unfinished Agenda: Women and the Legal Profession.” ABA Commission on Women in the Profession. Accessed November 24, 2018. http://womenlaw.law.stanford.edu/pdf/aba.unfinished.agenda.pdf (↵ Return)

Rosenthal, Cindy S. 1998. When Women Lead: Intergrative Leadership in State Legislatures. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Segal, Jennifer A. 2000. “Representative Decision Making on the Federal Bench: Clinton’s District Court Appointees.” Political Research Quarterly 53 (1): 137–150. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290005300107 (↵ Return)

Shapiro, Martin and Alec Stone Sweet. 2002. “On the Law, Politics, and Judicialization.” Oxford Scholarship Online. doi 10.1093/0199256489.001.0001. (↵ Return)

Siegle, Del. 2019. “Educational Research: Ttest.” University of Connecticut. Accessed January 2, 2019. https://researchbasics.education.uconn.edu/t-test/# (↵ Return)

Songer, Donald R., Sue Davis, and Susan Haire. 1994. “A Reappraisal of Diversification in the Federal Courts: Gender Effects in the Courts of Appeal.” Journal of Politics 56 (2): 425–439. (↵ Return)

Supreme Court of the United States. “Sandra Day O’Connor, First Woman on the Supreme Court.” Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.supremecourt.gov/visiting/SandraDayOConnor.aspx

Thomas, Susan 1997. “Why Gender Matters: The Perceptions of Women Officerholders.” Women and Politics 17 (1): 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1300/J014v17n01_02 (↵ Return)

Thornton, Margaret. 1996. Dissonance and Distrust: Women in the Legal Profession. Australia: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Tiller, Emerson H. and Frank B. Cross. 2006. “What is Legal Doctrine.” Northwestern University Law Review 100 (1): 517–533. (↵ Return)

Tuan Anh Nguyen v. INS, 121 S.Ct. 2053, 533 U.S. 53 (2001). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/533/53/

United States Courts. 2019. “Code of Conduct for United States Judges.” Accessed January 2, 2019. https://www.uscourts.gov/judges-judgeships/code-conduct-united-states-judges

US Legal Definitions. 2019. “Judicial Independence Law and Legal Definition.” Accessed January 2, 2019. https://definitions.uslegal.com/j/judicial-independence/

Walker, Thomas G. and Deborah J. Barrow. 1985. “The Diversification of the Federal Bench: Policy and Process Ramifications.” The Journal of Politics 47 (2): 596–617. doi: 10.2307/2130898 (↵ Return)

Wilson, Bertha. 1990. “Will Women Judges Really Make a Difference?” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 28 (3): 507–522. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol28/iss3/1 (↵ Return)

Class Activity

Please thoughtfully consider and respond to the questions below. You may need to pull up information online to assist you in your response.

- The term judicial independence refers to keeping the judiciary away from encroachments by the political branches of government, meaning the executive and the legislature (US Legal Definitions 2019). The term judicial impartiality refers to judges’ respect and compliance with the law and their acting in a manner that supports and promotes public confidence (United States Courts 2019). Bearing these definitions in mind, if all judges are tasked to act with independence and impartiality, does gender diversity matter in the Court? Why or why not?

- As the results of the chapter discussion, women judges do not always rule from an ethics of care perspective, and there is diversity among the female justices of the Supreme Court in terms of the language style they use. Would you expect to find a similar pattern for female legislators? Would you expect female legislators to legislate in a different voice than their male counterparts? Why or why not?

- The analysis presented in this chapter looks at particular types of cases (gender, LGBTQ+, health care, and religious liberty). Would you expect to find similar findings in different issue areas? What might those other categories of cases be? What it would mean if the pattern of results with different case areas were the same as discussed in this chapter?

- I would like to thank my former research assistant at CSU, Bakersfield, Nicole Mirkazemi, for her coordination and efforts with collecting and organizing this data set/sample of cases. ↵

- Although per curiam opinions refer to decisions from an appellate court that does not identify a specific judge as authoring the opinion (Legal Information Institute 2018), they were not dropped from the analysis in order to have a complete sample of opinions for the time period specified. Moreover, per curiam opinions represented a small portion of the sample (2.4 percent) and hence would not have significantly impacted the results. ↵

- Note that only one opinion for the category of LGBTQ+ cases was female-authored. Therefore, individual t-tests between the women in this category of cases were not done; however, the LGBTQ+ cases are still part of the aggregate analysis when comparing male and female justices and the language associated with the ethics of care and the ethics of justice across the entire sample. ↵