Media

16 Legitimacy, Trust, and Cameras in the U.S. Supreme Court

Ryan C. Black; Timothy R. Johnson; Ryan J. Owens; and Justin Wedeking

Introduction

In May 2020, two unprecedented events occurred at the US Supreme Court: the justices held oral arguments remotely (via telephone), and more importantly, they allowed the public to listen to those arguments online as they occurred.[1] The Court made these changes because the government’s response to COVID-19 prevented justices, counsel, and spectators from meeting in open court.[2] Once the Court allowed real-time access, it was impossible to stop it. When the justices returned to in-person arguments in October 2021, they continued to livestream their proceedings.[3] And on September 28, 2022, the Court issued a press release stating that it would continue to livestream arguments in the 2022 term. The world could continue to listen to oral arguments as they occurred. No longer would the Court’s small courtroom (and distant location) prevent the public from hearing its oral arguments contemporaneously.[4]

The Court’s decision to livestream the audio of its oral arguments broke with its long-standing practices. Previously, the Court allowed only in-person access to its oral arguments. With a seating capacity of 50–100 people, only a handful of people could listen to the justices’ oral arguments. What’s more, the Court previously prohibited non-Court personnel—even reporters—from recording its proceedings (Schubert et al. 1992; Wasby et al. 1976; Carter 2012; Houston et al. 2023). Though the Court began recording the audio of its arguments in 1955, it simply sent those files to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). It did not release audio files to the public until 1993. But even after the 1993 rules change, the Court did not publicly release its oral argument audio files (with rare exception) until the beginning of its next term, well after most Americans had forgotten about the past term’s cases.[5]

Not until the beginning of the 2010 term did the Court release audio in a timely manner (then, at the end of each argument week).[6] Just prior to the pandemic, the Court decided to release the audio files the same day it heard a case, but the release still occurred hours after the proceedings took place.[7] By livestreaming the audio, the Court significantly expanded access to the public.

Yet for all the significant enhancements to the audio of oral argument proceedings, the justices still have not permitted cameras to allow the public to hear and see oral arguments. Those who support cameras argue they will increase accountability, educate the populace, and enhance trust in the Court. Those opposed argue that placing cameras in the courtroom will allow the media to misrepresent what justices really do and decrease trust in the Court. The justices face a dilemma. Opening the courtroom to cameras could allow the public more access but at the risk of increasing or decreasing public trust in their institution. And as an unelected branch, the Court requires public trust to maintain its power.

In this chapter, we examine whether people’s trust in and support for the Court varies as a function of how they access oral arguments. We provide results from two experiments conducted more than a decade apart.[8] The first experiment varied the medium through which individuals received information about oral arguments. Some people read a written transcript of the proceedings; others listened to an audio recording of them. The results of this first experiment show that people’s support for the Court does not differ as a function of whether they read or listened to the arguments.

The second experiment exposed people to real video clips of oral arguments in two US state supreme courts. While we again focus on the medium by which individuals receive information, here we compare video versus audio. And in keeping with the concerns about what types of clips might be spotlighted by the media, we examine whether the contentiousness (neutral or contentious) of exchanges between an attorney and judge affects people’s overall trust that they have in the Court as an institution. We find that watching a clip has little effect on trust—compared to listening to that same exchange—and contentiousness does not increase or decrease trust. Moreover, we find that, when compared to people who were not exposed to any treatment (our control group), trust levels of those who watched a clip were significantly higher. Our results, when combined with previous research, underscore the complicated nature of placing cameras in the Supreme Court during oral arguments.

Judicial Legitimacy and Cameras in Courtrooms

Because courts often lack an electoral connection to voters, they must mind their institutional support and undertake actions that meet the public’s expectations of proper judging. Courts cannot implement their own decisions. They cannot raise their own funds. They do not have public relations experts to improve their images. Yet courts require public support. Without it, they may not be able to persuade recalcitrant public officials, private actors, and others to comply with their decisions. To survive as effective institutions, courts must meet the public’s expectations of what they are supposed to do. The closer judges come to meeting these expectations, the more legitimacy courts acquire.

Determining what the public expects of judges is a complicated endeavor (Gibson and Caldeira 2012, 2009a). Some research argues that the public’s support for courts is tied to substantive support for its decisions (Zilis 2021; Christenson and Glick 2015). Under this theory, people support courts that render case outcomes they like. And they will rein in courts that render case outcomes they dislike (Bartels and Johnston 2020).[9] While this line of scholarship is making serious headway in the literature, a long-standing line of scholarship advocates for a different view: a process-based theory of legitimacy.

The process-based theory claims that courts build and maintain support by making decisions that are based on law, logic, and history and by doing so in a fair and objective manner. “Procedural theories predict that people will focus on how decisions are made, not [just] on the decisions themselves, when making evaluations of fairness” (Tyler 2021, 736; emphasis added). If a “judge treats [people] fairly by listening to their arguments and considering them, by being neutral, and by stating good reasons for his or her decision, [litigants] will react positively to their experience, whether or not they receive a favorable outcome” (Tyler 2021, 6; emphasis added). Research shows that citizens are more likely to support court rulings (or at least recognize the theoretical importance of those rulings) when they internalize the judiciary’s institutional legitimacy (Nelson and Tucker 2021; Nelson and Gibson 2020; Gibson and Nelson 2015; Caldeira and Gibson 1992). Accordingly, courts can generate a strong base of institutional loyalty when they employ fair procedures and are perceived to treat people fairly (Gibson et al. 1998; Gibson and Caldeira 2011).

How might cameras influence judicial legitimacy and trust in the court system? Other than Bartels and Johnston’s (2020, 100) finding that people who disagree with the Supreme Court’s decisions are slightly more likely to support cameras in the US Supreme Court than people who agree with them, scant quantitative research examines the link between cameras and support for courts (but see Lee et al. 2022; Black, Owens, Johnson, and Wedeking 2023). That dearth of data, however, has not stopped people from hypothesizing the effects of cameras.

Some people argue that putting cameras in courtrooms, particularly in the US Supreme Court, will enhance judicial legitimacy. Research suggests that knowledge leads to support or, as one article pithily said, “to know it is to love it” (Gibson and Caldeira 2009b, 437). Increased transparency through televising oral arguments could educate the citizenry about the high court, presumably show that it is different from the “political branches,” and thereby enhance its legitimacy. The public might see justices engaged in legal and constitutional discussions that show they are not simply politicians in robes.

Similarly, it is possible that televising oral arguments would model proper civic behavior. Justices and attorneys discussing serious constitutional issues with civility and intelligence could act as role models. Justice Elena Kagan once stated, “[Cameras] would allow the public to see an institution working thoughtfully and deliberately and very much trying to get the right answers, all of us together” (Wolf 2019). The public may reward their good behavior with increased support.

Still, others argue that cameras will harm judicial legitimacy. They worry that the media will reduce a complex and largely collegial oral argument to a short, unrepresentative video clip that focuses on conflict. Justice Antonin Scalia argued that video clips would “miseducate and misinform” the public (C-SPAN 2011). Justice David Souter formed similar beliefs during his time on the New Hampshire Supreme Court, which allowed cameras. “My fifteen-second question would be there…[but used such that] it would create a misimpression either about what was going on in the Courtroom, or about me, or about my impartiality” (Souter 1996).[10]

Experiment 1

Theory and Hypotheses

Alexander Hamilton famously wrote of the judiciary that “it may truly be said to have neither force nor will, but merely judgment” (1788; emphasis in original). A long line of scholarship has attempted to understand how people react to the Court’s actions. Perhaps the most ubiquitous finding from much of this research is that the Supreme Court enjoys a deep reservoir of goodwill—a “positivity bias” (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2003a, 2003b). This reservoir of goodwill appears to stem at least partly from the fact that public confidence in the Court is rooted more in general support for the Court as an institution rather than specific support for the justices and their decisions (Caldeira and Gibson 1992).

Some research suggests this reservoir might be close to bottomless. Consider the Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore (2000). While commentators predicted the Court’s decision would undermine its legitimacy, a survey fielded by political scientists shortly after the decision showed almost no impact on its legitimacy (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2003a). If deciding a contentious presidential election is unable to move the needle, then it seems as though very little—cameras potentially included—can diminish the Court’s standing in the eyes of the public. These findings bode well for camera supporters.

More recent scholarship, however, suggests that exposure to disliked Court decisions can endanger the Court’s legitimacy. Examining the effects of Bush v. Gore, Nicholson and Howard (2003) find that diffuse support (i.e., institutional loyalty) for the Court varied depending on how the decision was framed. When the framing emphasized the justices’ motives as ending the election, diffuse support dropped. When the framing emphasized partisan motives, diffuse support remained constant (while specific support for the decision dropped).

Two other studies help inform our theoretical expectations. Zink, Spriggs, and Scott (2009) use textual vignettes to show that decisional attributes, such as the vote split, influenced an individual’s likelihood of accepting a case outcome as legitimate, with acceptance being more likely when a decision is unanimous versus divided. In a different vein, Gibson and Caldeira (2009) show that when people perceive televised confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominees in a negative light, the Court’s legitimacy can suffer. Viewed as a whole, these findings suggest that when the public observes conflict and fighting, the Court’s much-touted reservoir of goodwill dries up. Thus, we expect that individuals who are exposed to oral arguments containing more disagreement will exhibit less trust in the Court.

Survey and Design

Our first experiment was an online survey experiment of all political science majors at a large public university in the Midwest. We contacted respondents in mid-March 2012 and invited them to participate in the study. Subjects who fully completed the survey were entered into a lottery to win 1 of 15 gift cards. We invited 635 subjects to participate and 116 fully completed the study.[11] We varied the medium by which respondents were exposed to oral argument content (audio versus text only) and the level of agreement present in the content itself (low versus high). Subjects assigned to the control condition received no oral argument content.[12]

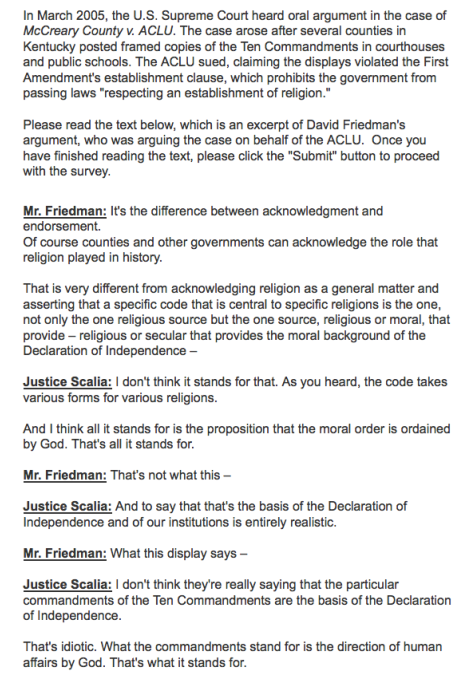

Our content came from the oral argument in McCreary County v. ACLU (2005). In this case, the Court sought to determine whether public schools or courthouses violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment when they displayed the 10 Commandments. Our respondents either read written transcripts or listened to excerpts from the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) attorney, David Friedman (see the appendix for the full excerpts). Our “low-agreement” segment features several exchanges between Friedman and Justice Scalia, including two instances where Scalia interrupted Friedman, and culminates in Scalia saying a particular argument is “idiotic.” We chose this segment precisely because of the sensational nature of the comment and the general disagreement between Justice Scalia and Friedman. The low-agreement segment is roughly 85 seconds long.

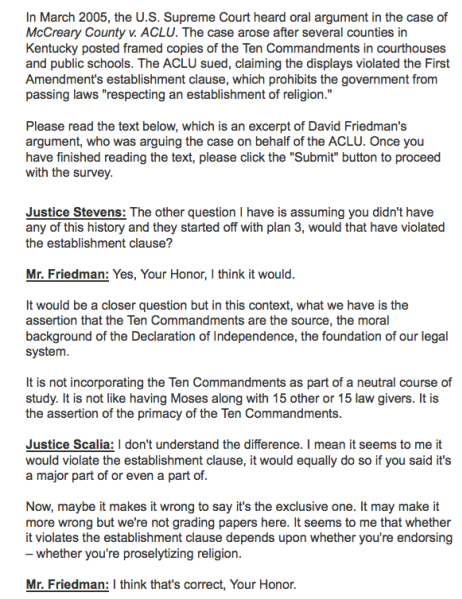

Our “high-agreement” segment, by contrast, starts with Justice Stevens asking a question, which Friedman addresses. Justice Scalia then makes a statement, and the segment concludes with Friedman agreeing with Scalia’s argument. This segment lacks the disagreement and punch of the comments in the low-agreement treatment. The segment also portrays oral arguments as a collective process, with at least two justices involved from opposite sides of the ideological spectrum. The high-agreement segment is approximately 77 seconds long.

After exposing subjects to their assigned segments, we presented them with a total of 10 statements designed to assess their attitudes toward the Supreme Court on legitimacy and trust—commonly referred to as institutional loyalty.[13] These statements generally measure legitimacy and trust. We asked respondents about the extent to which they agree with propositions such as

- “The Supreme Court can usually be trusted to make decisions that are right for the country as a whole,”

- “The right of the Supreme Court to decide certain types of controversial issues should be reduced,” and

- “The US Supreme Court gets too mixed up in politics.”

Respondents provided their replies on a five-point Likert scale that consists of (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) agree, (5) strongly agree.[14] To be thorough, we constructed two different indexes for our dependent variables.

The first index is a simple summative scale that adds each subject’s responses to the 10 questions, resulting in a measure that has a possible range from 10 (low institutional loyalty) to 50 (high institutional loyalty).[15] As an additional test of our argument, we computed a second index variable—a 10-point scale—coded as the total number of pro-Court responses a subject provided to each of the 10 loyalty questions. We consider a response pro-Court if the subject either agreed or strongly agreed with the propositions—for example, “The Supreme Court can usually be trusted to make decisions that are right for the country as a whole.” This second index variable is a different test because it does not account for any nuance between responding with “strongly agree” as opposed to merely “somewhat agree.” That is, it is only interested if the respondent gives a pro-Court response.

Summary of Results

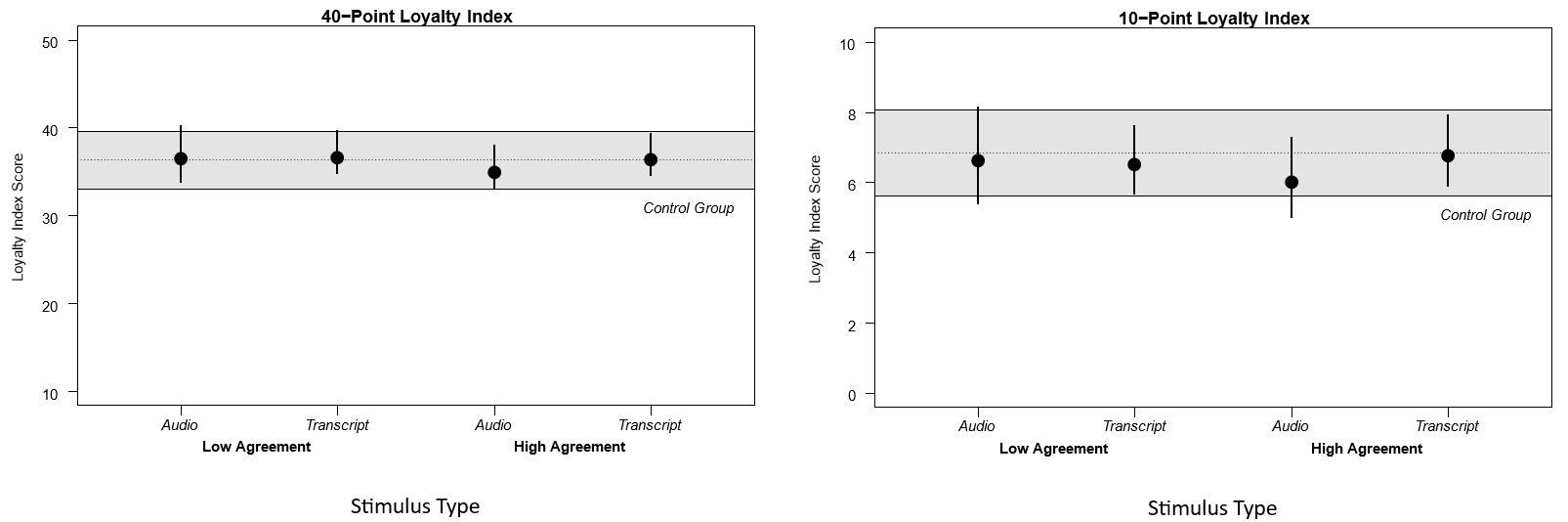

Figure 1 shows the results for whether exposure to oral arguments influences institutional loyalty. The top figure shows the results for our 40-point index, and the bottom figure shows our 10-point index. The dots represent the means for the four experimental conditions. The horizontal dashed line represents the mean for the control group. The whiskers around the dots represent 95% confidence intervals (and the shaded region indicates the corresponding confidence interval for the control group, which received no oral argument content). In general, institutional loyalty does not significantly differ among exposure to the different treatments. People showed just as much support for the Court when they read a transcript as when they listened to an oral argument in either the low-agreement or the high-agreement conditions.

Our first survey experiment tends to suggest that whether they read oral argument transcripts or listened to clips and whether they were exposed to low- or high-agreement clips, respondents supported the Court about the same. These results bode well for those seeking cameras in the Supreme Court. They suggest that the Court can withstand even low-agreement audio conditions.

Experiment 2

Theory and Hypotheses

Research suggests that video may have stronger effects on legitimacy than audio does. As such, we are next interested in comparing how watching an oral argument differs from listening to it. Studies find that “video is processed more superficially, and therefore users believe in it more readily [than audio] and share it with others” (Sundar et al. 2021, 301). Watching a video news clip decreases the depth of processing as compared to reading and listening (Powell et al. 2018). As Slotnick and Segal (1998, 7) write, “Telenews has the ability to portray events with a sense of realism and emotional drama that other forms of news do not.” Video “can transport you to the scene and can tell you quickly what is at issue in a rather simple way” that audio cannot (Slotnick and Segal 1998, 47).

In one relevant study, Druckman (2003) reexamined the conventional wisdom of the 1960 presidential debate, which held that radio listeners thought Nixon won the debate while television viewers thought Kennedy won it. Using an experiment that had participants evaluate the candidates after either listening to the debate or watching a televised version (with sound), Druckman found that television increased people’s reliance on personality perceptions while audio led them to focus on issues (2003, 567). This comports with earlier findings that show audio-only exposure to the news enhances understanding, while audiovisual is more emotionally arousing (Crigler et al. 1994).

Video likely has a greater influence than audio because of its “presence.” Presence is a subjective sense of immersion within a mediated environment. It reflects how much a person feels they are involved with what they are observing. (We will address presence—and the camera angles that enhance it—more fully below.) Video delivers more presence than audio. It is more imaginable, which makes the message more believable and potent (Sundar et al. 2021, 303; Yadav et al. 2011). That is why media focuses on visuals when possible and why audio does not hold out the same hopes or fears as video. Indeed, media has access today to audio clips of oral arguments. And the media could, if it wished, disseminate audio clips of oral arguments that might educate or mislead. But audio does not capture the public the same way as video. It does not have the same presence. “Television and film, more than newspapers or radio, provide an approximation of human experience in terms of visual and aural sensory input” (Mutz and Reeves 2005, 4). Video is important, then, because it can enhance a message’s impact.

Accordingly, cameras could enhance the benefits of observing positive behavior. Video, and its enhanced presence, has a unique ability to highlight what Tyler (1989) has called “standing.” Standing (or “status recognition”) examines how politely, respectfully, and fairly authorities treat people. A friendly exchange between judge and attorney could showcase good standing. Research shows that politeness toward those in a legal conflict can enhance perceptions of fair treatment. Tyler and Rasinski (1991) note that people’s views about the fairness of legal institutions’ decision-making procedures influence their legitimacy and willingness to accept their decisions. Krewson (2019) similarly finds that justices who “remind” people about the Supreme Court’s constitutional role can enhance its legitimacy. When people believe procedures are fair, they accord institutions more legitimacy. And so viewing a positive exchange could improve people’s support for courts.

Conversely, cameras could exacerbate the harm that might come from observing negative behavior. A contentious exchange between an authority and a subject can increase tensions or, at minimum, lead to feelings of unease. Mutz and Reeves (2005) examined how civil or contentious two politicians were during a televised political discussion. When the politicians acted politely and civilly, the respondents maintained trust in institutions. But when the politicians raised their voices, interrupted, or displayed negative nonverbal cues (e.g., shaking their heads), respondents trusted them less. Television simply operates in an environment where people can see themselves existing. And the discomfort associated with observing contentious exchanges between or among people is easier to observe—and more likely to be felt and personalized—from watching television than from audio.[16] In short, the wrong message seen on video could significantly harm a court.

This discussion brings us back to “presence” and, importantly, camera angle. As anyone who has ever watched a movie can attest, things like camera angles and scene changes affect how a viewer takes in and processes the video. Some presentations can enhance presence and cause viewers to feel as though they are part of the scene, such as when one sees through the eyes of a character. For example, Lombard and Ditton (1997) find that rapid movement of the point of view improves viewers’ presence. Similarly, when examining feelings of fan presence watching a college football game, Cummins (2009) compared the images from a largely static sideline shot to a skycam that portrayed a subjective perspective with changing angles. He found that the skycam angle elicited a greater sense of presence.

This research shows that videos presented more dynamically are more likely to enhance subjects’ presence in the scene (Cummins et al. 2012) and are associated with increases in emotional arousal, memory, and sustained attention (Lang et al. 2000; Simons et al. 2003). In contrast, videos with fewer scene changes (i.e., they are more static) are associated with significant decreases in emotional arousal, memory, and sustained attention (Lang et al. 2000; Simons et al. 2003).

In a recent study, we examined the impact of medium (video versus audio), contentiousness, and camera angle on legitimacy (Black, Owens, Johnson, and Wedeking 2023). We found that static angles do not appear to influence legitimacy but that using dynamic angles might have a limited effect. Watching a neutral exchange might increase judicial legitimacy—compared to listening to that exchange—but watching a contentious exchange might decrease it. In a second experiment, we examined whether the presence of judicial symbols interacts with these effects. Evidence here is suggestive that these symbols could mitigate the negative effect of exposure to contentious content.

The existing literature leads us to three expectations. First, we expect that respondents who watch a neutral exchange will find courts and judges to be more trustworthy than respondents who listen to it. The exchange will represent all the virtues camera supporters suggest: modeling good behavior, watching civil and intelligent dialogue, and educating the public. Second, we expect that respondents who watch a contentious exchange will find courts and judges to be less trustworthy than respondents who listen to it. The increased personalization that comes from the visuals, coupled with the discomfort of the exchange, may lead people to be less supportive of courts. Third, we expect that dynamic clips—but not static clips—will exacerbate the effects of neutral or contentious exchanges on trust in the judiciary. The presence that comes from the dynamic clip will magnify the effects of the good behavior (neutral exchanges) and the effects of the bad behavior (contentious exchanges).

Survey and Design

To execute this experiment, we utilized the Lucid Theorem. Though a convenience sample, Lucid improves upon earlier platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk by using respondent quotas to achieve a census-balanced sample. Lucid samples provide demographic and experimental results that track well with US national benchmarks (Coppock and McClellan 2019) and are increasingly common in experimental studies like ours (see, e.g., Fang and Huber 2019). Conducted in late April 2020, the survey experiment employed a total of 1,475 respondents.[17]

The first dimension of the design manipulated the contentiousness of the exchange between the judge and the attorney.[18] In the contentious clip, a justice aggressively questioned the attorney, interrupted him, and appeared impatient. The neutral clip featured the same attorney, the same justice, in the same case, and on the same general topic but showed them engaged in a different set of unremarkable exchanges. Given the potentially subjective nature of this distinction, we validated our clips before using them by measuring differences in vocal pitch. We also implemented a short battery of questions in the experiment itself to confirm that respondents perceived the content difference. They did.[19]

The second dimension of the design manipulated the clip’s modality. Respondents either watched the video clip (with sound) or listened to the audio without video. The final condition was a control where respondents neither viewed nor listened to an oral argument clip.[20]

Generating the video clips for our experiment posed a number of challenges. Most federal appellate courts and many state courts do not allow cameras in their courtrooms, which limits the jurisdictions where we could find video. Just as important, we wanted courts whose video or audio lacked anything that allowed a respondent to discern the specific court we used. Although we did not attempt to deceive our respondents into thinking they were seeing or hearing a particular court, we sought to protect our results from being influenced by respondents’ state-specific or court-specific attitudes. We chose to use actual clips rather than embed clips within mock news reports to make sure the responses were a result of the courtroom footage itself and not attributable to media coverage, which some respondents might find biased (either favorably or unfavorably). Ultimately, we selected oral arguments from two state supreme courts—Minnesota and Indiana.[21]

As we show below, Minnesota’s camera perspective was static, whereas Indiana’s camera perspective was dynamic. These two perspectives represent the two general ways courts record oral arguments. Figure 2 depicts screen captures from each court. The left panel shows the Minnesota Supreme Court, which employed a static wide-angle shot of the full bench from a distance. It also captured a side view of the attorney. Given the camera’s distance from the attorney and the justices, the viewer could not easily see their facial expressions. Instead, the viewer observed the full complement of justices and the attorney.

The Indiana Supreme Court, in contrast, used multiple camera angles and scene changes. Cameras located behind the bench and behind the attorney shifted to whoever spoke at a particular moment (much like the “speaker view” in a Zoom meeting). This dynamic approach made it possible to see the faces of the attorney and the justice during an exchange but came at the cost of not being able to see the court as a full body.

We assigned respondents to one of eight clip conditions (contentiousness × modality × two states) and provided them with a few sentences of background material about the case stimuli they would see or hear. Then after we exposed them to the stimuli, we asked them questions to assess whether they paid attention to the argument and whether they recognized the manipulations (i.e., contentious versus neutral). Individuals assigned to the control group did not hear or see an argument clip. Therefore, we did not ask them the manipulation check questions.[22] We then asked all respondents to rate their agreement on a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree) with a number of survey items. Here we focus on the results for an item we have not yet otherwise reported on, which was the following statement: “The courts can usually be trusted to make decisions that are right for the country as a whole.” Overall, the descriptive results across all conditions were as follows: 19% strongly agree, 42% somewhat agree, 24% neither agree nor disagree, 11% somewhat disagree, and 3% strongly disagree. For the empirical analysis that we present below, we convert these responses to a fraction, such that 0 represents strongly disagree, 0.5 is neither agree nor disagree, and 1 represents strongly agree.

Empirical Results

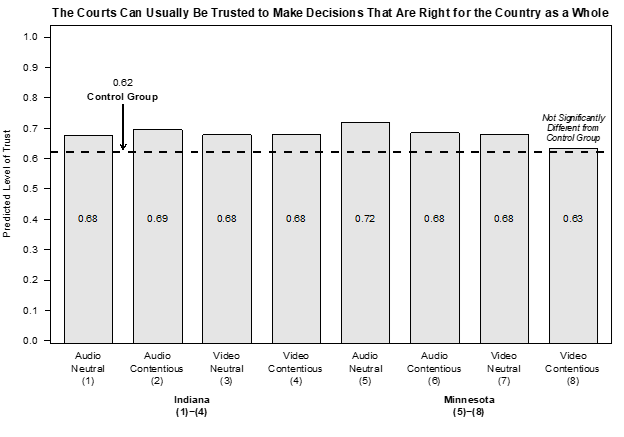

Figure 3 visualizes the predicted level of trust score (y-axis). Along the x-axis, we show each of our eight treatments, grouped such that respondents exposed to Indiana materials are on the left half of the figure and respondents exposed to Minnesota materials are on the right half of the figure. The dashed horizontal line running across the figure denotes the level of trust for the control group, which observed no oral argument materials at all.

We first evaluate whether exposure to any type of oral argument content has an appreciable effect on respondents’ level of trust. In other words, are there any differences between the treatment groups and the control group? The answer is nuanced. In terms of statistical significance, we find a significant increase in trust for seven of the eight treatments as compared to the control group.[23] We find no significant difference between the control group and the Minnesota Video Contentious treatment (8). This would suggest, at first blush, that to see a court “in action” increases the level of trust one has in courts.

Why, then, do we say the results are nuanced? Statistical significance is a necessary but insufficient condition for concluding that something “matters.” Statistical significance establishes that a difference we observe is unlikely to have occurred by chance alone, but it does not establish that a difference is substantively meaningful. For example, suppose we told you that studying more would yield a statistically significant increase in your grade in the (undoubtedly terrific) class for which you are reading this chapter. You would (rightfully) be interested in this finding. But you would probably also want to know how much more you needed to study and how big a grade increase you would observe. If we told you that an extra hour per week would raise your grade by 10%, that would be a great trade-off. Alternatively, if we told you that the same extra hour per week would only yield a 1% increase in your grade, you would probably find yourself doing something else instead.

When examining our results through the lens of substantive significance, prudence demands that we are far more circumspect about our results. Respondents in our control group—those who did not see or hear any oral argument content—have a trust level of about 0.62. The highest value we observe among the treatment groups is 0.72, which is the predicted value for respondents assigned to the Minnesota audio neutral condition (i.e., #5). This is an absolute increase of 0.10 (i.e., 0.72–0.62) and is a relative change of about 16% (i.e., 0.72/0.62). But in terms of the overall distribution of the trust measure, a 0.10 increase corresponds to just two-fifths of one standard deviation of that measure, which is to say that this is not much of an increase.

We turn next to working our way through the various hypotheses. Recall that our first two expectations involved the interplay between the modality by which respondents experienced oral argument (video versus audio) and the nature of the content (neutral or contentious).

Neutral Exchanges

We first examine how exposure to neutral audio or video influences trust in the judiciary. We expected that video exposure would lead to higher trust relative to audio-only exposure and that the effects would be greater in the dynamic condition. We can again turn to figure 3 to assess this question. Respondents assigned to the Indiana materials had predicted trust scores of 0.68 when they watched a video of the neutral oral argument exchange, which is identical to the values of those who only listened to it. As for respondents in the Minnesota conditions, those who watched the neutral clip perceived the court to be slightly less trustworthy (0.68) than those who listened to it (0.72), but this difference is not, itself, statistically significant. In short, there is no evidence that trust is differentially impacted when individuals watch neutral oral argument content versus when they listen to it. Cameras do not appear to increase support even under favorable conditions.

Contentious Exchanges

Figure 3 also presents the analogous results for contentious content. We expected that exposure to video of this content would lead to lower trust attitudes relative to audio-only exposure and that the effects would be greater in the dynamic condition. In the Indiana content, we recover no meaningful differences between individuals who saw the contentious exchanges versus those who listened to them. In the Minnesota conditions, however, we do find some modest evidence of a systematic effect. Individuals who watched a testy exchange between the attorney and judge had a predicted trust score of 0.63. By contrast, those who listened to that same exchange had a predicted trust score of 0.68. This difference has a p value of 0.08, which is too close to statistical significance to dismiss out of hand. That being said, the size of the difference—0.05—is half the size of the earlier one we already discussed and dismissed as being substantively unimpressive. Ultimately, we believe this provides weak support for our second hypothesis. Cameras seem to decrease support, weakly, under unfavorable conditions.

Finally, recall that our third hypothesis suggested a role to be played by the style of the video presentation. More specifically, dynamic presentation should result in a heightened impact for contentious content as compared to a static presentation. Figure 3 again allows us to assess the evidence for this hypothesis. Among those in the static video condition (Minnesota), exposure to neutral content had a predicted trust score of 0.68 versus a predicted trust score of 0.63 when exposed to contentious content. This difference of 0.05 has a p value of 0.12, which puts it in the statistical gray zone: it is not statistically significant but also is not so far off the mark that we could emphatically conclude that no difference exists. As for those in the dynamic video condition (Indiana), we find no real difference at all. Respondents exposed to both the neutral and the contentious content have predicted trust scores of 0.68. This runs contrary to our hypothesis, which expected to find an effect for dynamic content but not for static content.[24]

Discussion

Our analysis provides evidence that focuses on the very important question of whether televising oral arguments will affect trust in the Court. We turned first to a text-versus-audio experiment. There did not appear to be any statistical relationship between the type of exposure and trust in the Court as an institution. Does this definitively answer the question of interest? Certainly not fully. Thus, we turned to a second experiment. Those findings indicate that exposure to any content from oral argument tends to result in a substantively small but statistically significant increase in the level of overall trust courts enjoy. On the other hand, we also find that video exposure to contentious content could be slightly harmful to how much people trust courts as compared to audio exposure of that same content. Still, even this result requires some caution because the size of the difference itself was slight.

In the end, the Court will continue to grapple with livestreaming the audio of its oral arguments, and it will continue to receive calls to allow cameras in its courtroom. Whether it chooses to allow cameras will turn on our findings and future work on cameras and legitimacy. More data and analyses are needed before the justices make any final decisions on this important issue.

Learning Activity

- Open the website oyez.org. The website is devoted to oral arguments at the US Supreme Court. With a partner, find the oral argument for McCreary County v. ACLU (2005) and listen to the two segments highlighted in the first experiment (see appendix for the transcripts, which should be searchable on Oyez). Do you hear any tone differences? Is the justice being argumentative? What do you think? Share your answers with a partner and speculate on how your thoughts match with the findings in the chapter.

- With a partner, navigate to the Indiana website that hosts video footage of its oral arguments (https://mycourts.in.gov/arguments/default.aspx?court=sup). Use the search options to select a case that has been argued and watch three to five minutes. Observe and note how the attorneys and justices speak and interact. Describe to a partner how this compares to what your expectations are for lawyers and judges to act in a courtroom.

References

Amira, Karyn, Christopher A. Cooper, H. Gibbs Knotts, and Claire Wofford. 2018. “The Southern Accent as a Heuristic in American Campaigns and Elections.” American Politics Research 46(6): 1065–93.

Armaly, Miles T. 2018. “Extra-judicial Actor Induced Change in Supreme Court Legitimacy.” Political Research Quarterly 71(3): 600–613.

Bartels, Brandon L., and Christopher D. Johnston. 2013. “On the Ideological Foundations of Supreme Court Legitimacy in the American Public.” American Journal of Political Science 57(1): 184–99.

Bartels, Brandon. L., and Christopher D. Johnston. 2020. Curbing the Court: Why the Public Constrains Judicial Independence. Cambridge University Press.

Berinsky, Adam J., Michele F. Margolis, and Michael W. Sances. 2014. “Separating the Shirkers from the Workers? Making Sure Respondents Pay Attention on Self-Administered Surveys.” American Journal of Political Science 58(3): 739–53.

Black, Ryan C., Timothy R. Johnson, Ryan J. Owens, and Justin Wedeking. 2024. “Televised Oral Arguments and Judicial Legitimacy: An Initial Assessment.” Political Behavior 46(2): 777–97.

Caldeira, Gregory A., and James L. Gibson. 1992. “The Etiology of Public Support for the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 36(3): 635–64.

Christenson, Dino P., and David M. Glick. 2015. “Chief Justice Roberts’s Health Care Decision Disrobed: The Microfoundations of the Supreme Court’s Legitimacy.” American Journal of Political Science 59(2): 403–18.

Coppock, Alexander, and Oliver A. McClellan. 2019. “Validating the Demographic, Political, Psychological, and Experimental Results Obtained from a New Source of Online Survey Respondents.” Research and Politics 6(1): 1–14.

Crigler, Ann N., Marion Just, and W. Rusell Neuman. 1994. “Interpreting Visual versus Audio Messages in Television News.” Journal of Communication 44(4): 132–49.

C-SPAN. 2011. “Cameras in the Court: Learn about the Justice’s Views on the Issue of Opening the Court to Cameras, Based on Their Public Statements.” http://www.c-span.org/The-Courts/Cameras-in-The-Court/. Accessed October 11, 2011.

Cummins, R. Glenn. 2009. “The Effects of Subjective Camera and Fanship on Viewers’ Experience of Presence and Perception of Play in Sports Telecasts.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 37(4): 374–96.

Cummins, R. Glenn, Justin R. Keene, and Brandon H. Nutting. 2012. “The Impact of Subjective Camera in Sports on Arousal and Enjoyment.” Mass Communication and Society 15(1): 74–97.

Druckman, James N. 2003. “The Power of Television Images: The First Kennedy-Nixon Debate Revisited.” The Journal of Politics 65(2): 559–71.

Druckman, James N., and Cindy D. Kam. 2011. “Students as Experimental Participants: A Defense of the ‘Narrow Data Base.’” In Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Political Science, edited by James N. Druckman, Donald P. Greene, and James H. Kuklinski, 41–57. Cambridge University Press.

Fang, Albert H., and Gregory A. Huber. 2019. “Perceptions of Deservingness and the Politicization of Social Insurance: Evidence from Disability Insurance in the United States.” American Politics Research 48: 543–59.

Gaines, Brian J., James H. Kuklinski, and Paul J. Quirk. 2007. “The Logic of the Survey Experiment Reexamined.” Political Analysis 15(1): 1–20.

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009a. Citizens, Courts, and Confirmations: Positivity Theory and the Judgments of the American People. Princeton University Press.

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009b. “Knowing the Supreme Court? A Reconsideration of Public Ignorance of the High Court.” The Journal of Politics 71(2): 429–41.

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2011. “Has Legal Realism Damaged the Legitimacy of the U.S. Supreme Court?” Law & Society Review 45(1): 195–219.

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2012. “Campaign Support, Conflicts of Interest, and Judicial Impartiality: Can Recusals Rescue the Legitimacy of Courts?” The Journal of Politics 74(1): 18–34.

Gibson, James L., Gregory A. Caldeira, and Vanessa A. Baird. 1998. “On the Legitimacy of National High Courts.” American Political Science Review 92(2): 343–58

Gibson, James L., Gregory A. Caldeira, and Lester Kenyatta Spence. 2003a. “Measuring Attitudes toward the United States Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 47(2): 354–67.

Gibson, James L., Gregory A. Caldeira, and Lester Kenyatta Spence. 2003b. “The Supreme Court and the US Presidential Election of 2000: Wounds, Self-Inflicted or Otherwise?” British Journal of Political Science 33(4): 535–56.

Gibson, James L., and Michael J. Nelson. 2015. “Is the U.S. Supreme Court’s Legitimacy Grounded in Performance Satisfaction and Ideology?” American Journal of Political Science 59(1): 162–74.

Gibson, James L., and Michael J. Nelson. 2018. Black and Blue: How African Americans Judge the U.S. Legal System. Oxford University Press.

Huber, Gregory A., and John S. Lapinski. 2006. “The ‘Race Card’ Revisited: Assessing Racial Priming in Policy Contests.” American Journal of Political Science 50(2): 421–40.

Jansen, Anja M., Ellen Giebels, Thomas J. van Rompay, and Marianne Junger. 2018. “The Influence of the Presentation of Camera Surveillance on Cheating and Pro-social Behavior.” Frontiers in Psychology 9(1937): 1–12.

Kennedy, Anthony. 1996. “Testimony before House Appropriations Subcommittee.” March 28. https://www.c-span.org/video/?70835-1/us-supreme-court-appropriations. Accessed July 15, 2024.

Krewson, Christopher N. 2019. “Save This Honorable Court: Shaping Public Perceptions of the Supreme Court off the Bench.” Political Research Quarterly 72(3): 686–99.

Lang, Annie, Shuhua Zhou, Nancy Schwartz, Paul D. Bolls, and Robert F. Potter. 2000. “The Effects of Edits on Arousal, Attention, and Memory for Television Messages: When an Edit Is an Edit Can an Edit Be Too Much?” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 44(1): 94–109.

Lee, Claire, Rorie Solberg, and Eric N. Waltenburg. 2022. “See Jane Judge: Descriptive Representation and Diffuse Support for a State Supreme Court.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 10(4): 581–96

Lombard, Matthew, and Theresa Ditton. 1997. “At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 3(2): JCMC321.

Morton, Rebecca B., and Kenneth C. Williams. 2008. “Experimentation in Political Science.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier, Henry E. Brady, and David Collier, 339–56.

Mutz, Diana C., and Byron Reeves. 2005. “The New Videomalaise: Effects of Televised Incivility on Political Trust.” American Political Science Review 99(1): 1–15.

Nelson, Michael J., and James L. Gibson. 2020. “Measuring Subjective Ideological Disagreement with the US Supreme Court.” Journal of Law and Courts 8(1): 75–94.

Nelson, Michael J., and Patrick D. Tucker. 2021. “The Stability and Durability of the US Supreme Court’s Legitimacy.” The Journal of Politics 83(2): 767–71.

Nicholson, Stephen P., and Thomas G. Hansford. 2014. “Partisans in Robes: Party Cues and Public Acceptance of Supreme Court Decisions.” American Journal of Political Science 58(3): 620–36.

Nicholson, Stephen P., and Robert M. Howard. 2003. “Framing Support for the Supreme Court in the Aftermath of Bush v. Gore.” The Journal of Politics 65(3): 676–95.

Patton, Dana, and Joseph L. Smith. 2017. “Lawyer, Interrupted: Gender Bias in Oral Arguments at the US Supreme Court.” Journal of Law and Courts 5(2): 337–61.

Powell, Thomas E., Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Knut D. Swert, and Claes H. de Vresse. 2018. “Video Killed the News Article? Comparing Multimodal Framing Effects in News Videos and Articles.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 62(4): 578–96.

Simons, Robert F., Benjamin H. Detenber, Bruce N. Cuthbert, David D. Schwartz, and Jason E. Reiss. 2003. “Attention to Television: Alpha Power and Its Relationship to Image Motion and Emotional Content.” Media Psychology 5(3): 283–301.

Slotnick, Elliot E., and Jennifer A. Segal. 1998. Television News and the Supreme Court: All the News That’s Fit to Air? Cambridge University Press.

Souter, David J. 1996. “Testimony before House Appropriations Subcommittee.” March 28. https://www.c-span.org/video/?70835-1/us-supreme-court-appropriations. Accessed July 15, 2024.

Sundar, S. Shyam, Maria D. Molina, and Eugene Cho. 2021. “Seeing Is Believing: Is Video Modality More Powerful in Spreading Fake News via Online Messaging Apps?” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 26(6): 310–19.

Tyler, Tom R. 1989. “The Psychology of Procedural Justice: A Rest of the Group-Value Model.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57(5): 830–38.

Tyler, Tom R., and Kenneth Rasinski. 1991. “Procedural Justice, Institutional Legitimacy, and the Acceptance of Unpopular US Supreme Court Decisions: A Reply to Gibson.” Law & Society Review 23(3): 621–30.

Wolf, Richard. 2019. “Cameras in the Supreme Court? Not Anytime Soon.” USA Today, March 7.

Yadav, Aman, Michael M. Phillips, Mary A. Lundeberg, Matthew J. Koehler, Katherine Hilden, and Kathryn H. Dirkin. 2011. “If a Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words Is Video Worth a Million? Differences in Affective and Cognitive Processing of Video and Text Cases.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 23: 15–37.

Zilis, Michael A. 2018. “Minority Groups and Judicial Legitimacy: Group Affect and the Incentives for Judicial Responsiveness.” Political Research Quarterly 71(2): 270–83.

Zilis, Michael A. 2021. The Rights Paradox: How Group Attitudes Shape US Supreme Court Legitimacy. Cambridge University Press.

Zink, James R., James F. Spriggs II, and John T. Scott. 2009. “Courting the Public: The Influence of Decision Attributes on Individuals’ Views of Court Opinions.” The Journal of Politics 71(3): 909–25.

Appendix: Experiment Materials

Experiment 1 Materials

We performed a randomization check on the data to ensure that there were no factors that explained subjects’ assignment to condition. This confirms that there are no observable differences across our five conditions.[25]

Experiment 2 Materials

To view the four video clips, you can visit the replication materials for Black, Johnson, Owens, and Wedeking (2023) hosted on the Harvard Dataverse website: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/IUANCE

- For information about oral arguments, see https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/oral_arguments.aspx (last accessed December 30, 2022). The importance of this cannot be understated. Indeed, while members of the press and a lucky few from the public who obtain seats in the courtroom experience arguments in real time, space is quite limited (see, e.g., https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/courtroomseating.aspx, last accessed December 30, 2022). We discuss this at length below. ↵

- During the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, the justices postponed arguments for a month. However, the technology did not then exist to hold remote arguments (see, e.g., https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/04/courtroom-access-faced-with-a-pandemic-the-supreme-court-pivots/, last accessed December 30, 2022). ↵

- https://www.supremecourt.gov/ (last accessed December 30, 2022). ↵

- https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/press/pressreleases/pr_09-28-22 (last accessed December 30, 2022). ↵

- The Court’s term starts on the first Monday of every October and runs through late June or early July the following year. The Court sometimes released audio of the proceedings in very high-profile cases on the same day as the arguments. See, e.g., Bush v. Gore (2000), Citizens United v. FEC (2010), and NFIB v. Sebelius (2012). ↵

- https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/press/pressreleases/pr_09-28-10 (last accessed December 30, 2022). ↵

- https://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/argument_audio/2021 (last accessed December 30, 2022). ↵

- This amount of time might seem excessive, but it is not all that unusual for scholars. They begin a project, as we did in 2012, then divert to something else and eventually return with (hopefully) better ideas. ↵

- Several studies find a connection between legitimacy and things like partisan or ideological agreement with decisions (Bartels and Johnston 2020; Zilis 2018; Christenson and Glick 2015; Nicholson and Hansford 2014; Bartels and Johnston 2013). ↵

- Some worry that cameras would lead attorneys to grandstand (Kennedy 1996). While that outcome is possible, it is worth noting that Jansen et al. (2018) find that people engage in “good behavior” in the presence of cameras. ↵

- Research by Druckman and Kam (2011) demonstrates that the use of student subjects does not pose a validity problem. ↵

- The subjects who completed the survey had these characteristics: 81% self-identified as white, while 19% self-identified as either Asian, Black, Hispanic, or other; 44% Democrat, 40% Republican, and 16% independent; the mean age was 20.9, with 91.23% of the respondents in the 18–22 range; 48% were seniors, 29% juniors, 14% sophomores, and 9% freshman. ↵

- Strictly speaking, the loyalty questions were not asked immediately after the experimental stimulus but rather after three background questions about a respondent’s experience with the judiciary (e.g., Have you ever served on a jury?). We did this for two reasons. First, we wanted to guard against the criticism that we were stacking the deck in our favor (of finding an effect) by asking the dependent measures too close to the stimulus (i.e., making it too obvious that it lacks credibility). Second, we wanted to avoid having the subjects easily detect the underlying relationships that we were interested in assessing. ↵

- Eight of our 10 questions were asked in succession after the three background experience questions described above. To account for the possibility that any treatment effects might be short lived, following the recommendation of Gaines, Kuklinski, and Quirk (2007), we asked the two final loyalty questions toward the end of the survey after asking approximately 23 other non-loyalty-based questions. We admit, this is a short duration, but it at least provides a minimal check that any experimental effect does not decay too rapidly to be meaningless in a political context. While we find that, in general, subjects (across almost all treatment categories) responded with higher loyalty in the initial eight questions as opposed to the latter two, the results we report below are unchanged by omitting the latter responses. ↵

- Because we used 10 questions to develop a scale that measures an individual’s loyalty or support toward the Court, we assessed some properties of the scale to ensure that our measures are reasonably sound. First, to ensure that all 10 items mapped onto one factor (and not two or more), we performed a factor analysis on the 10 items, keeping any factor with an eigenvalue greater than one. The factor analysis returned a single factor. Second, to ensure the reliability of the scale, we computed Cronbach’s alpha (a way of assessing reliability by comparing the amount of shared variance, or covariance, among the items making up an instrument to the amount of overall variance), which, at 0.84, is well above generally acceptable levels. ↵

- Relatedly, Crigler et al. (1994) found that subjects were most emotionally aroused in the audiovisual condition. And emotion has been associated with decreases in court legitimacy (Armaly 2018). ↵

- We fielded the survey after the Supreme Court announced it would hold teleconferenced oral arguments (April 13, 2020) but before it provided the specific details of how it would operate such proceedings (April 30, 2020). Nearly all our respondents took the survey on April 24, 2020, which is when we launched it. The reader can watch the experimental materials by visiting the Harvard Dataverse page for Black et al. (2023), which is located at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/IUANCE (last accessed June 22, 2023). ↵

- In all of our stimuli, both the attorneys and judges are white males, which holds constant race and gender. Varying both of these in future studies would be useful given existing work on, for example, legitimacy and race (Gibson and Nelson 2018) as well as on gender and oral argument (Patton and Smith 2017). ↵

- Because we used real-world materials, we could not manipulate only the tone or manner in which the exchanges took place while holding constant the actual words being spoken. Thus, there are differences in the stimuli aside from the tone and behavior of the justice. See the supplementary materials for Black et al. (2023) for additional discussion of this point. ↵

- As we note above, most appellate courts already record (and often livestream) audio of their proceedings, which means, as a policy matter, audio is a natural baseline (Morton and Williams 2008). We still include a control group that lacks any stimuli at all (Gaines et al. 2007), as it allows us to evaluate how a change to video might impact individuals who would be newly exposed to oral argument content (presumably due to increased media coverage of the proceedings). ↵

- As both of these states are midwestern, this means we also held constant possible differences in the accents of the speakers—justices and attorneys alike. This is noteworthy since accents from some regions—particularly the north (e.g., New York) and the south—are perceived less favorably than others (Amira et al. 2018). Note, additionally, that none of the Minnesota speakers sounded like someone from the movie Fargo. ↵

- As with any survey experiment, there was variation in the seriousness with which respondents completed the assigned tasks (Berinsky et al. 2014). The results we describe below include all respondents in the analysis. ↵

- There are different levels one can use to determine whether something is (or is not) statistically significant. The most common is the so-called 95% level. Another one that also is used frequently is the 90% level. If you’re into splitting hairs, then five of our six significant results pass at the 95% level. The sixth, Indiana Audio Neutral (1), passes at the 90% level. The one that is not significant, Minnesota Video Contentious, is not even close to passing at any level. ↵

- Sometimes this is just the way the cookie crumbles in social science. Now having seen the results, we do have some thoughts about why it might have shaken out in this particular way. Our use of real-world materials did not allow us to formally manipulate the video presentation style. That is, the ideal video clips would portray the same exact set of exchanges in both a static and dynamic manner. As this was not possible here (we did not use actors), it means that the difference, which we attribute to the difference in presentation style, could be driven by other variations between the two courts’ materials. ↵

- For the details, similar to Huber and Lapinski (2006), we use a multinomial logit model to predict the condition as a function of age, race, partisanship, religious worship, and two opinion items measuring religious predispositions. All the variables are statistically insignificant, and the entire model, as indicated by the likelihood ratio chi-square test, is also statistically insignificant. ↵