Decision Making

2 In Her Words

An Analysis of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Use of Emotive Language in Her Authored Dissenting Opinions

Nicolas Ellis and Jennifer Bowie

The effective judge, I believe…strives to persuade, and not to pontificate. She speaks in a “moderate and restrained” voice, engaging in a dialogue with, not a diatribe against, co-equal departments of government, state authorities, and even her own colleagues.

—Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Introduction

During the spring of 2020, which marked Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s final months on the Supreme Court, the world was engulfed by the coronavirus pandemic, relegating the justices to their homes to hear oral arguments by teleconference, to vote, and to craft their opinions beyond the inner sanctums of the Supreme Court. In her last dissenting opinion, before her death, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg forcefully condemned the Court’s curtailment of women’s access to contraception. The seven-justice majority in Little Sisters of the Poor Saints Peter and Paul v. Pennsylvania exempted religious organizations from providing contraceptive coverage in their health plans per the requirements of the Affordable Care Act. Justice Ginsburg decried the threat to family planning on female autonomy that this ruling posed. In her dissent, Justice Ginsburg criticized the Court by writing, “Today for the first time, the Court casts totally aside countervailing rights and interests in its zeal to secure religious rights to the nth degree.”[1] Though only a vignette of her career, Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinion in the Little Sisters of the Poor case is emblematic of the understated force that she brought to so many of her written opinions that led to her public anointment as the “Notorious RBG” in 2013.

Since her designated status as the Notorious RBG, claims have routinely been made that as she became more famous, “her dissenting opinions became increasingly fiery” (Rosen 2019, 132) and that she had emerged as a “forceful and passionate dissenter” (Guinier 2015, 206). Despite Justice Ginsburg’s celebrity and cultural icon status as a crusader for the underdog, judicial scholars know little about whether her rhetoric and communication style changed over her career on the Court. While the world around her insisted she had altered her dissenting opinion writing style, she refuted that idea in a 2014 interview. In the interview, Jeffrey Rosen noted that she seemed to have recently found her voice, and he asked her “what changed” (Rosen 2019, 137–38). Justice Ginsburg answered, “Jeff, I don’t think I changed. Perhaps I was a little less tentative than I was when I was a new justice. But what really changed was the composition of the Court” (138). This leads us to ask whether Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinion writing style changed over time. More specifically, did she use more emotive language in her authored dissenting opinions over her career, particularly after becoming known as the Notorious RBG?

With such increased public exposure, the audience that a justice reaches invariably changes (Garoupa and Ginsburg 2009; Black et al. 2016a), arguably resulting in a subsequent shift in the use of language to communicate with their different audiences, whether it be the public, the judicial community, or the members of legislative bodies (Baum 2006; Epstein and Knight 1997; Krewson 2019). Among the several points in the judicial decision-making process for which language is critical, dissenting opinions offer a particularly apt lens for analyzing the use of emotive language given its function as a means to articulate disagreement with a decision, often by communicating with external audiences (Johnson et al. 2009; Krewson 2019; Ryan 2016).

We build upon earlier scholarship that examines the use of emotive language at different stages of the judicial-making process (Bryan and Ringsmuth 2016; Corley and Wedeking 2014; Gleason 2019, 2020, 2023; Hinkle 2017; Hazelton and Hinkle 2022; Rice and Zorn 2016; Wedeking and Zilis 2018). Specifically, we investigate Justice Ginsburg’s use of emotive language in her authored dissenting opinions throughout her career using a language-based software program called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). In this study, we analyze (1) Justice Ginsburg’s emotional language usage in her dissenting opinions over her career, (2) whether Ginsburg’s use of emotive language in her authored dissenting opinions before and after becoming the “Notorious RBG” differs, and (3) whether case salience, the ideological direction of the majority opinion, issue area, and opinion vote breakdown affect the frequency and degree to which she utilizes emotive language.

We find that although Ginsburg’s use of emotive language did not change at the inflection point of 2013, she used significantly more emotive language in liberal dissenting opinions than conservative ones, in civil rights and liberties cases, and in cases decided by a minimum-winning coalition (such as 5–4 or 4–3 decisions). Although Ginsburg’s career as a lawyer, judge, and justice is well documented among scholars of the Court, journalists, and civil rights activists alike, this study analyzes her time on the bench through a new lens, contributes to the robust lineage of scholarship on judicial opinion writing, and offers several paths for further research that could work in concert with this study to further develop our understanding of the Court.

The Paramountcy of Language in Judicial Opinion Writing

Scholarship shows the language that justices decide to use throughout the opinion writing stage plays a crucial role in the judicial decision-making process, from how a decision is received by the general public to how other political actors in the legislative and executive branches react to a given decision (Owens et al. 2013; Krewson 2019). It has been well established that Supreme Court justices are decision makers who operate in an interdependent environment that includes other justices and political actors beyond the Court (Epstein and Knight 1997; Epstein and Jacobi 2010). Numerous studies demonstrate there are several ways justices can influence policy. For instance, justices can explicitly support one position over another by virtue of their vote on a given case (Epstein and Knight 1997; Segal and Spaeth 2002), they have discretionary influence over the cases heard by their agenda-setting powers (Black and Owens 2012), and they can use judicial review to overturn legislation (Epstein and Knight 1997). However, not only do the decisions justices make constrain political and legal actors in the present and those immediately affected by the case, but the content of their opinions also constrain future actors and have a powerful, lasting impact (Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth 2016; Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000; Carlson, Livermore, and Rockmore 2015; Corley, Collins, and Calvin 2011). Therefore, it follows that the specific language justices use to craft an opinion is painstakingly selected and has critical implications for understanding judicial decision making (Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth 2016; Corley 2008; Corley, Collins, and Calvin 2011; Bowie and Savchak 2022), the extent to which decisions are implemented (Hume 2009), the rule of law and stare decisis (Owens and Wedeking 2011), and judicial strategy (Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth 2013). Fundamentally, the language used by appellate courts is of preeminent importance given their ability to set precedents. The opinions justices write create legal doctrine that lower court judges must adhere to in addition to articulating legal principles and interpretations of legal documents that help guide policymakers (Corley, Collins, and Calvin 2011; Bowie and Savchak 2022).

Writing with a Judicial Voice

In opinion writing as well as certain other areas of the judicial process, scholarship demonstrates that writing in a neutral “judicial voice” is typically more successful than using emotionally laden language (Scalia and Garner 2008; Gleason 2019). For instance, in exploring the reception of legal briefs by appellate judges in the Supreme Court and at the circuit level, Black, Hall, Owens, and Ringsmuth (2016) find that justices are more likely to vote for parties whose briefs “eschew” emotionally charged language, as justices view that type of language as damaging to that party’s credibility and, in some cases, consider it unprofessional (see also Hazelton and Hinkle 2022). Because judges and justices have been trained and socialized in the traditional “rule of law” approach, which values objective and logical argumentation (see Massaro 1989; Scalia and Garner 2008), they find legal briefs that directly appeal to logic, avoid irrelevant or emotive language, and have reasoned arguments are most successful before appellate judges, even when controlling for attorney quality (Black, Hall, Owens, and Ringsmuth 2016).

Likewise, Corley and Wedeking (2014) find that opinions issued by the Court are treated more positively or adhered to more often by lower courts when the language of those opinions contains more “certain” or assertive and concise language. Their findings are undergirded by empirical research that finds more assertive messages to be more persuasive (Hazelton, Cupach, and Liska 1986; Sniezek and Buckley 1995). Pivoting to the influence of other legal actors in the federal judicial process, Corley (2008) examines the influence of litigant briefs on justices’ written opinions. She finds that justices borrow language from briefs from the solicitor general’s office, Washington elite attorneys, and more experienced attorneys—those attorneys who are more credible and likely to use reasoned, logical writing to express their arguments. Bowie and Savchak (2022) look at this similar “borrowing” phenomenon in opinion writing and examine the influence of state court opinions on Supreme Court opinion writing. They show that justices are more likely to borrow from state court opinions that are written more clearly in terms of the use of active voice as compared to passive voice. Altogether, these findings demonstrate that legal writing is generally more persuasive among members of the legal community when it is more reasoned, certain, and clear. Justice Ginsburg herself echoed this sentiment in a lecture she gave at New York University, saying that the role of a judge is to “persuade, not pontificate” (Ginsburg 1992, 1186). Therefore, to be successful and impactful, justices should write more logically, concisely, and with less emotionally charged language.

Yet Gleason and colleagues (2019, 2020, 2023), in a series of studies analyzing oral arguments, find that female litigants are more successful when they avoid the traditional expectation that actors in the judicial process communicate in a neutral “judicial voice.” While rarely deterministic, the stakes are high at oral arguments because they can shape the contours of judicial decision making (Black, Johnson, and Wedeking 2012; Johnson 2004; Johnson et al. 2006) and can sway a justice sitting on the proverbial fence (Ringsmuth, Bryan, and Johnson 2013). Clearly, the language litigants select is fundamental to their success. However, scholarship demonstrates that gender permeates through language (Butler 1999; Jones 2016), and scholars note a number of measurable differences in how men and women communicate in the amount of emotional language used (Pennebaker 2011; Newman et al. 2008; Schwartz et al. 2013). For instance, women use emotional language more often than men (Chaplin 2015; Newman et al. 2008), and people subconsciously hold both men and women to these standards of communication (Mulac et al. 2013). Gleason (2020) finds that female attorneys are more successful at oral arguments when they conform with gender norms by using more emotive language relative to male attorneys, incongruent with the prevailing wisdom that more concise, logical language is the superior mode of communication at the Court across groups.

The Different Audiences That Justices Reach

As suggested earlier, justices operate in an interdependent environment that includes those beyond the legal community—their fellow justices, litigants, lower court judges, and the general public, to name a few. Baum (2006), in his work on judges and their audiences, explains that it is unrealistic to conceptualize judges and justices as individuals so far removed from their social environments and the constant inundation of the public at large. For example, scholarship analyzing the private papers of Justices Marshall, Brennan, and Powell found that Court members regularly clip articles and editorials about specific cases, thus providing evidence that justices pay attention to how their decisions are perceived by various audiences (Epstein and Knight 1997).

Garoupa and Ginsburg (2009) and Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth (2016) distinguish between two primary audiences that justices engage with: internal and external. For example, Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth (2016) refer to internal audiences as members of the judiciary and legal community and external audiences as the media and general public. In his seminal work on judicial behavior, Murphy (1964) finds that justices recognize their limited ability to singularly achieve their legal policy goals and “may succeed in influencing…segments of public opinion so that the effectiveness of opposition to the Court’s decisions will be reduced or positive cooperation induced.” This sentiment comports with a fundamental tenet of the strategic account of judicial decision making put forth by Epstein and Knight (1997). Justices must consider the preferences of other political actors, including the public, to achieve their legal policy goals. Employing a strategic theoretical framework, Casillas and colleagues (2011) find support for this notion when examining the degree to which public opinion affects justices’ voting. Even after controlling for the influence of social forces, they demonstrate that public mood has a significant short- and long-term influence on the Court’s decisions—as the public shifts in a liberal direction, the Court issues more liberal decisions in the short term, even after controlling for Court composition, and this will affect the justices’ collective decision making during the following term (Casillas et al. 2011).

Why Dissent?

Dissenting opinions are distinct from majority opinions in several clear and more nuanced ways. Justice Ginsburg (2010) described the multifaceted utility of dissenting opinions. In terms of their in-house impact, she found that there is “nothing better” than an impressive dissent to cause the author of the majority opinion to refine and clarify their initial circulation of opinions before a decision ultimately goes public (Ginsburg 2010, 3). In addition, she recognized that other dissents aim at propelling legislative change (Ginsburg 2010). Justices also use dissenting opinions as a means for suggesting to future litigators, judges, and justices a different lens through which to view a case with the hopes of impacting the legal policy on a given issue. By doing so, they can signal to litigators that they have a “friend” on the Court if they were to pursue overruling the case on which the given justice wrote a dissenting opinion (Johnson et al. 2009). Exploring the factors that cause justices to read their dissents from the bench, Johnson and colleagues (2009) find that justices will participate in oral dissents when they care a good deal about the issue and when they want to change the policy set by the majority. Justice Ginsburg’s (2010) perception comports with the findings of Johnson et al. (2009). She explained, “A dissent presented orally, therefore, garners immediate attention. It signals that, in the dissenters’ view, the Court’s opinion is not just wrong, but grievously misguided” (Ginsburg 2010, 2).

When writing a dissent, justices employ language that is often distinct from the “judicial voice” used in majority opinions to instruct an already engaged audience. One of the most important roles of a dissenting opinion is to explain the disagreement with the majority opinion (Ginsburg 2010). Additionally, dissenting opinion writers know they do not need to win over votes or maintain any majority (Bryan and Ringsmuth 2016). Bryan and Ringsmuth explain, “Dissents may be designed to contribute to the public debate on a given issue” (2016, 164). In analyzing the sensationalism in the language of Supreme Court written opinions and dissents, Krewson (2019) finds that rather than instructing, justices are seeking to grab the attention of a nonlegal audience and influence them through emotional appeals in dissenting opinions. Additionally, Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth (2016) found that even Justice Antonin Scalia used rhetorical devices and emotive language in his written opinions not to appeal to his “internal” audience but rather with the intention of reaching and influencing the general public. In tandem with the understanding that justices appeal to different audiences, it follows that justices are, to varying degrees, conscious of the manner in which the language they select for their dissenting opinions affects their external audience. These findings suggest that justices are implicitly, if not explicitly, cognizant of their external audience when writing majority and dissenting opinions.

It is surprising, therefore, that few studies specifically examine the trends in language that individual justices use in their dissenting opinions throughout their tenure on the Court. Given that the decision to dissent and the language a justice uses when authoring any written opinion is vital to the judicial decision-making process (Peterson 1981), examining the manner in which an individual justice writes their dissent, including the emotive quality of their language, would shed valuable light to understanding judicial behavior. Thus we suggest that studying Justice Ginsburg’s 25-year tenure through the lens of emotional language in her written dissenting opinions can provide novel insight into her judicial style and relationship with her external audience.

Justice Ginsburg’s Judicial Style and Rise as the Notorious RBG.

Court observers describe Ginsburg as a justice who favored a gradualist approach to changing the law and whose written work is generally pragmatic, not delivering decisions that are unnecessarily broad in scope (Slobogin 2010; Shapiro 2004). For example, Slobogin (2010) explains, in his analysis of Fourth Amendment cases, that Ginsburg engaged in two forms of gradualism. Occasionally, Justice Ginsburg engaged in “positive” gradualism by writing or joining a majority opinion that tried to emulate her famously incrementally attained success in gender discrimination cases by moving the Court in a defendant-oriented direction (Slobogin 2010). However, most of her gradualism has been of the “negative” variety, meaning that she has attempted to constrain a prosecution-oriented majority coalition through concurring and dissenting opinions by pointing out the limitations of the majority’s ruling without threatening the collegiality of the Court (Slobogin 2010). In regard to her proceduralist approach, Yip and Yamamoto (1998) find that Ginsburg utilized a proceduralist approach in her decision making and judicial writings. Yip and Yamanto (1998) suggest that Ginsburg avoided language that may “disrupt the balance among process values” in future cases while acknowledging that a certain level of dynamism is necessary to accommodate different case types (672). Taken together, these examinations portray Ginsburg as a justice who (1) understands the value of procedural guardrails to judicial decision making, (2) is reluctant to issue sweeping changes that fundamentally change the rule of law on a given issue, and (3) avoids disturbing collegiality on the Court in one fell swoop.

To further understand her perspective, in a 1992 speech at New York University, she quoted Justice William Brennan’s defense of dissenting opinion: “None of us…must ever feel that to express a conviction, honestly and sincerely maintained, is to violate some unwritten law of manners or decorum. I question, however, resort to expressions in separate opinions that generate more heat than light” (Brennan 1986, 437). Justice Ginsburg, in the same speech, later said that language “impugning the motives of a colleague” does not have a place in a dissent, as it threatens collegial relations on the Court. Scholarship on Ginsburg’s tenure on the Court, along with her own words, emphasize that maintaining collegiality was of utmost importance to her (Ginsburg 1992; Ginsburg 2010; Shapiro 2004; Barnhart and Zelesne 2004). Even when examining dissenting opinions in gender discrimination cases, Barnhart and Zelesne (2004) show that Ginsburg navigated the fine line between advocating for the rejection of gender-role stereotypes that repress women and maintaining collegiality among judges, “proving that her twin objectives of gender equality and collegiality are not mutually exclusive” (Barnhart and Zelesne 2004, 312). Taken together with her gradualist and “values proceduralist” approach, it follows that Ginsburg, in her early years on the Court, would be unlikely to pen dissenting opinions that used overly emotive language that may disturb the collegiality of the Court or fly in the face of precedent. Though this scholarship is helpful in understanding the early years of Justice Ginsburg’s tenure on the Court and foundational elements of her judicial style, it leaves out her critical later years on the Court, during which she embraced her celebrity status as the “Notorious RBG.”

The Notorious RBG

In the 2010s, Ginsburg increasingly found herself as a liberal bulwark against the growing conservative majority on the Court. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which struck down a significant portion of the Voting Rights Act, Ginsburg authored a “strongly worded dissent” that she read aloud, signaling her acute disagreement with the majority opinion. Following this decision, New York University law student Shana Khizhnik started a Tumblr blog titled Notorious RBG, whose virality thrust Ginsburg into a new echelon of public glorification among not just the liberal legal community but also the public at large.[2]

Though there is ample prose and journalistic coverage of Justice Ginsburg in these later years and the Court as a collective, there is a lack of scholarship on her individual judicial-style postidolization, notably a comprehensive examination of trends in her use of language in her dissenting opinions. After garnering increased exposure in the public eye, we suggest that Ginsburg’s relationship with her external audience changed in some foundational way (Garoupa and Ginsburg 2009; Baum 2006; Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth 2016; Krewson 2019). Based on Krewson’s finding that justices use increasingly sensational, emotive language as their public audience becomes more relevant, we expect that Ginsburg used increasingly more emotive language in her dissenting opinions as a means to communicate with her public audience.

H1: Justice Ginsburg Used More Emotive Language in Her Dissenting Opinions Post–Notorious RBG Status

Scholarship has noted that salient cases may be on a different footing than nonsalient cases (Corley, Collins, and Calvin 2011; Canelo 2022; Epstein and Segal 2000). For example, in salient cases, the justices might expend more time and energy shaping the content of the majority opinion than in relatively trivial disputes (Corley 2008; Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000). Furthermore, Johnson et al. (2009) find that when a case is particularly salient, a judge’s or justice’s beliefs are more intensely held.

H2: Justice Ginsburg Used More Emotive Language in Salient Cases

Like case salience, civil rights and liberties are issue areas that are high stakes due to increased public exposure to these cases and the passion that justices feel on these issues (Lewis and Rose 2014; Unah and Hancock 2006). Given that justices may be impassioned by cases that deal with civil rights and liberties issues (Bryan and Ringsmuth 2016), it follows that Justice Ginsburg would use more emotive language in her dissenting opinions on civil rights and liberties issues than other case types.

H3: Justice Ginsburg Used More Emotive Language in Civil Rights and Liberties Cases

The use of emotive language may be more prevalent in closely divided cases. Such divisions indicate a clear-cut disagreement over the policy set by the majority. In other words, a justice may be more distraught about a majority decision in these cases than when the justices reach a unanimous or near-unanimous decision. Therefore, we suggest that Justice Ginsburg would use more emotive language in these closely decided split decision cases than in cases decided by larger majority coalitions.

H4: Justice Ginsburg Used More Emotive Language in Split Decision Minimum-Winning Coalition Cases

Finally, numerous studies have shown that ideology matters in judicial decision making (Segal and Spaeth 2002; Zorn and Bowie 2010). Additionally, scholars have found that justices are strategic actors and that their ability to achieve their policy goals depends on the preferences and choices of other actors (Epstein and Knight 1997). Marrying these theoretical accounts with the understanding that justices are cognizant of public opinion and that they use more sensational, or emotive, language in written opinions as their external audience becomes more relevant, it follows that justices would use more emotive language in dissenting opinions that are ideologically congruent to their preferences in response to the majority opinion. In other words, we suggest that Justice Ginsburg will use more emotive language when she is writing ideologically liberal dissenting opinions (in response to conservative majority opinions) than conservative dissenting opinions (in response to a liberal majority opinion), particularly given the heightened public receptiveness their audience will have to those opinions (Casillas et al. 2011; Krewson 2019; Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth 2016).

H5: Justice Ginsburg Used More Emotive Language in Ideologically Liberal Dissenting Opinions (Conservative Majority Opinion) Than in Conservative Dissenting Opinions (Liberal Majority Opinion)

Data and Methods

Our goal involves examining Justice Ginsburg’s use of emotional language in her dissenting opinion over her career on the US Supreme Court. We utilize data from existing data sources along with our own extensive data collection effort. Using the Spaeth et al. (2022) Supreme Court Database, we begin by identifying all dissenting opinions on the merits authored by Justice Ginsburg during her tenure on the Court from the 1993–2019 terms (this covers the 1994–2020 time period). Overall, our data includes 144 authored dissenting opinions on the merits.

Because we are focusing on analyzing Ginsburg’s language in each dissenting opinion she wrote, we looked up each dissenting opinion in the Nexis Uni database and copied and pasted each dissent into separate text files (where each dissent has its own text file). Our analysis uses the LIWC software to measure the amount of emotional language present in each dissenting opinion within our data. LIWC is a dictionary-based computer application program that analyzes text files. LIWC reads a given text, compares each word in the text to the list of dictionary words, and calculates the percentage of total words in the text that match each dictionary category (Pennebaker et al. 2015). LIWC provides 90 output variables and matches them to the dictionary words within the software (Pennebaker et al. 2015). In other words, LIWC analyzes the language in each file, looking for characteristics like emotion, tone, affect, and so on. While other programs exist to evaluate the emotive content of texts (e.g., the Dictionary of Affect in Language [DAL]), we use LIWC because of its demonstrated internal and external validity (see, e.g., Pennebaker and King 1999; Kahn et al. 2007; Tausczik and Pennebaker 2010). LIWC has been used in research across the social sciences, from psychology (e.g., Niederhoffer and Pennebaker 2009), to sociology (e.g., Bell, McCarthy, and McNamara 2006), to, more recently, judicial politics (Bryan and Ringsmuth 2016; Corley and Wedeking 2014; Hinkle 2017; Hazelton and Hinkle 2022; Rice and Zorn 2016; Wedeking and Zilis 2018). To create the dependent variable, we run all the dissenting opinion text files through the LIWC software to obtain the percentage of emotional language used in each dissenting opinion (Pennebaker and King 1999). To measure this variable, we use the LIWC emotion variable, which calculates the percentage of emotional words—positive or negative—in a dissenting opinion. The dependent variable ranges from 0 (no emotional language) to 25.6%.

Independent Variables

We are also interested in understanding the variation in emotional language used in Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinions. We include several independent variables to explain when we might expect more emotive language to be utilized in a dissenting opinion. Our first independent variable, Notorious RBG status, indicates whether the dissenting opinion was written after Justice Ginsburg was named the “Notorious RBG.” This variable is coded 1 if the dissent was written after the last day of the 2012 term and 0 if the dissent was written before this date. We include a variable that accounts for case salience because we recognize that case importance may evoke more emotional language than nonsalient cases. We use the Epstein and Spaeth (2000) CQ Salience measure, which denotes whether the case is designated a landmark decision by the Congressional Quarterly. The case salience variable takes a value of 1 if designated a landmark case and 0 otherwise. Our third independent variable, civil rights and liberties, indicates whether a civil rights and liberties issue is present in the case.[3] Epstein and Segal (2000) and Bryan and Ringsmuth (2016) demonstrate that constitutional civil liberties and other civil rights cases may evoke stronger preferences in the justices and the public. Using the Spaeth et al. (2022) issue area variable (which codes for the predominant issue area in each case), we classify the following issue areas as civil rights and liberties issues: First Amendment, privacy, due process, and civil rights. This variable is coded as 1 if the case possesses a civil rights and liberties issue and 0 otherwise. We include a variable to account for split decisions (decisions made by a minimum-winning coalition). Cases decided by a 5–4 or 4–3 majority take a value of 1, and all other vote distributions (e.g., 6–3, 7–2, 8–1) take a value of 0. We include a variable that accounts for the ideological direction of the majority decisions. We use the Supreme Court Database’s decision direction variable, which indicates whether the majority opinion is conservative or liberal. This variable takes a value of 1 if the majority opinion is conservative and 0 for liberal decisions.[4] Finally, because longer opinions provide a greater opportunity to write with more emotional language, we include a control variable, opinion length, which measures the total number of words in the opinion. To make this variable easier to interpret, we divide the number of words by 1,000 (see Savchak and Bowie 2016; Canelo 2022).

Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of our data. Our data include the percentage of emotional language used in each of Justice Ginsburg’s dissents during her time on the US Supreme Court. During her tenure on the Court, we find her dissenting opinions averaged approximately 5.37% emotional language and that she used emotional language in approximately 92% of her dissenting opinions. Since we are interested in how her use of emotional language in her dissenting opinions evolved over time, we calculate the mean emotional language by term.

| Issue area | Percentage of dissents | Average amount of emotional language used (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Attorney | 2 | 2.13 |

| Civil rights and liberties | 32 | 5.12 |

| Criminal procedure | 24 | 4.32 |

| Economic activity | 22 | 5.20 |

| Federalism | 4 | 7.69 |

| Judicial power | 11 | 4.90 |

| Unions | 2 | 7.50 |

| Misc. | 1 | 2.80 |

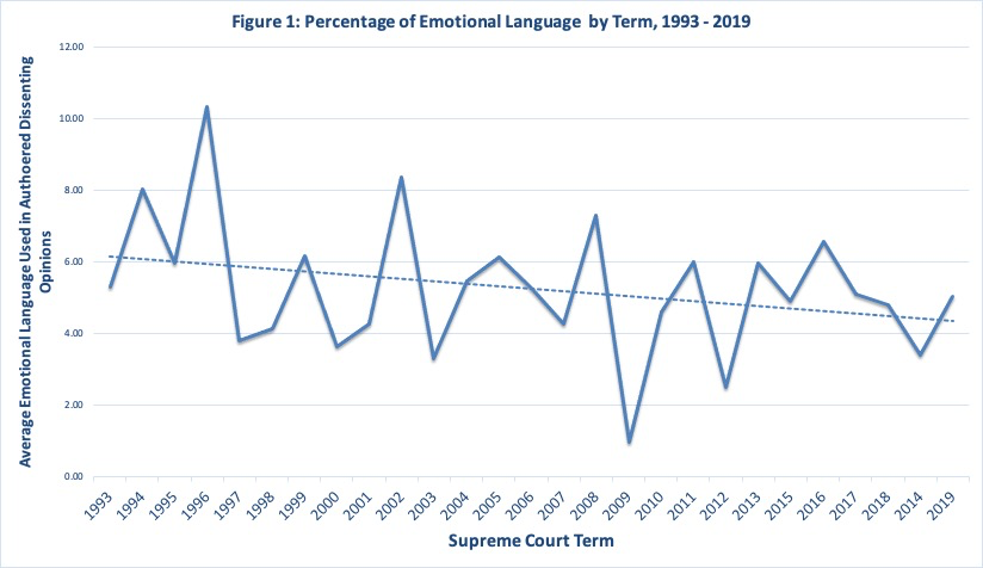

Figure 1 provides an overview of the average amount of emotional language Justice Ginsburg used over her career. As figure 1 shows, Justice Ginsburg’s emotional language usage varies over time. We find that Justice Ginsburg averaged the most emotional language in the 1995 term and the least in the 2009 term. While we do not see an upward increase in emotional language usage over time by term, we do, however, find a slight uptick in the average emotional language usage from the 2012 and 2013 terms. Figure 1 shows that after the Notorious RBG label, her use of emotional language increased from approximately 2% in the 2012 term to 6% in the 2013 term but then leveled off in the remaining years.

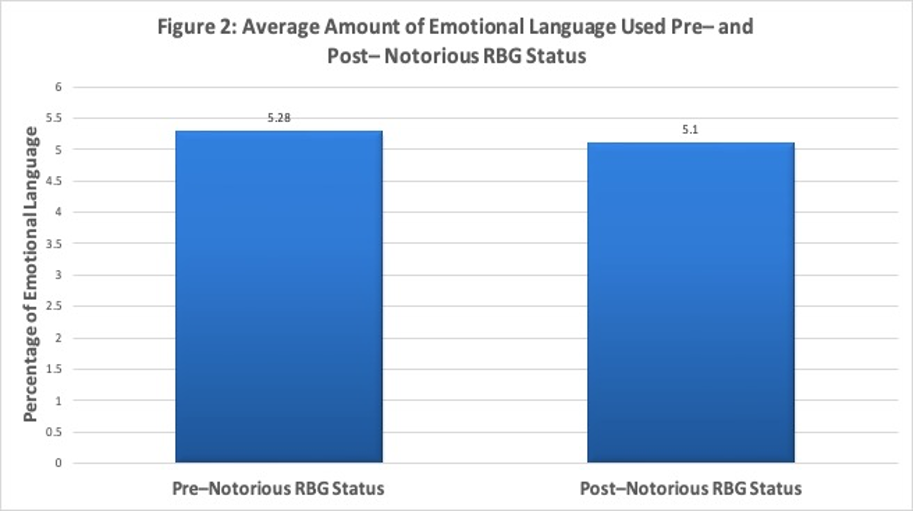

Popular accounts of Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinions suggest that she wrote more emotional and poignant dissents later in her career. Figure 2 illustrates the average amount of emotional language used in her dissenting opinions pre–Notorious RBG status (1994–2012 terms) and post–Notorious RBG status (2013–19 terms). As figure 2 demonstrates, there was no increase in emotional language. In fact, figure 2 reveals a slight decrease in the average amount of emotional language used in dissenting opinions post–Notorious RBG status.

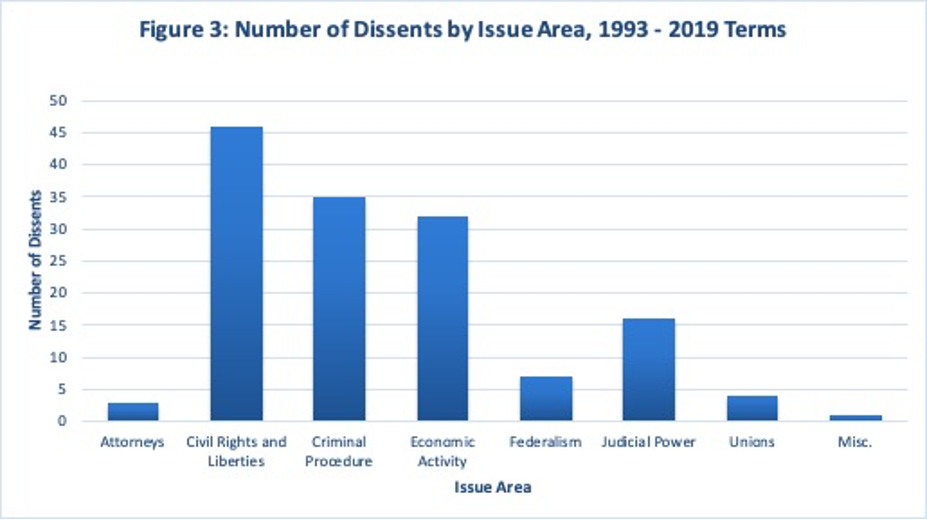

Figure 3 displays the number of dissents by issue area that Justice Ginsburg wrote while in the Court. The results indicate that Justice Ginsburg wrote the most dissents in civil rights and liberties cases, closely followed by criminal procedure and economic activity cases. Table 2 provides trends in her dissenting behavior by issue area and provides the average amount of emotional language used by issue area. To highlight, while federalism and union cases make up approximately 4% and 2% of the dissents she wrote, respectively, both issue areas evince the most emotional language used when compared to the other issue areas. For civil rights and liberties cases, we see that, on average, when Justice Ginsburg wrote a dissent for this case type, she used approximately 5.12% of emotional language.

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation | Min–max |

|---|---|---|---|

| Civil rights and liberties issue | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0–1 |

| Split decision | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0–1 |

| Conservative majority opinion | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0–1 |

| Case salience | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0–1 |

| Notorious RBG status | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0–1 |

| Opinion length | 3.00 | 2.35 | 0.03–10.98 |

| Dependent variable | – | ||

| Emotional language | 5.37 | 4.37 | 0–25.6 |

N = 144

Because of the continuous nature of our dependent variable, we estimate a linear regression model to directly test how our independent variables influence the amount of emotional language used in her dissenting opinions. Our results are reported in table 3. We have suggested several variables that might provide insight into the variation of emotional language used in Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinions. First, we proposed that if popular accounts were correct, Justice Ginsburg would use more emotive language in her authored dissenting opinions after her celebrity became a fixture in popular culture in 2013 given the larger external audience she reached. As our results illustrate, we did not find support for this hypothesis. The coefficient estimate for RBG status is not statistically significant, indicating that her popular icon status did not positively or negatively influence her use of emotional language. Counter to media accounts, we do not find evidence that her emotional language usage in her dissenting opinions increased after her Notorious RBG status. However, this finding in some ways should be unsurprising given that Justice Ginsburg herself put a premium on collegiality in the Court, even when she wrote her dissenting opinions.

| Independent variable | Expectation | Coefficient estimate | Robust standard error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Civil rights and liberties issue | + | 1.176* | 0.85 |

| Split decision | + | 1.32* | 0.74 |

| Conservative majority opinion | + | 1.57* | 0.67 |

| Case salience | + | −0.76 | 0.97 |

| Notorious RBG status | + | 0.10 | 0.75 |

| Opinion length | N/A | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| Constant | N/A | 2.71* | 0.81 |

N = 144

Note: The dependent variable is the percentage of emotional language in the dissenting opinion. *p < .05 (one-tailed tests).

We, however, find support for several of our other independent variables. We suggest that civil rights and liberties cases would provide opportunities, given the nature of the issue area, to write dissenting opinions with more emotional language. In substantive terms, we find that dissenting opinions with civil rights and liberties issues include approximately 1.75% more emotional language than those cases without. This finding shows that the nature of the issue, here civil rights and liberties, evokes more emotional language usage than other issue areas. We also find support that closely decided cases increase the amount of emotional language Justice Ginsburg used in her dissenting opinions. For instance, the statistically significant coefficient estimate split decision shows that Ginsburg used 1.33% more emotional language when the case was decided by a minimum-winning coalition (cases decided by a 5–4 or 4–3 majority).

We hypothesized that when the majority decision is ideologically conservative (which means she wrote an ideologically liberal dissenting opinion), Justice Ginsburg would utilize more emotional language in her dissenting opinion. Our statistically significant coefficient estimate for conservative majority decision provides support that Ginsburg used more emotional language in her liberal dissenting opinions. Clearly, responding to conservative majority reasoning evokes more usage of emotional language. Our results indicate that Ginsburg used approximately 1.56% more emotional language in her dissenting opinion when the majority opinion was ideologically conservative. In other words, when Justice Ginsburg wrote an ideologically liberal dissent, she used more emotional language. We find no statistically significant support that case salience influenced emotional language usage.[5] Justice Ginsburg did not use more or less emotional language when an important issue was present. Similarly, we find no support for our control variable, opinion length. Interestingly, the number of words in a dissenting opinion does not positively or negatively influence emotional language usage.

Conclusion

Scholarship on the use of language throughout the judicial decision-making process, particularly in written opinions, shows that though speaking or writing in a “judicial voice” is nominally the most effective means of communication, using emotive language can be effective in dissenting written opinions and other stages of the judicial process when an external audience is more acutely involved or aware (Krewson 2019; Gleason 2020; Garoupa and Ginsburg 2009; Black, Owens, Wedeking, and Wohlfarth 2016). Our research shows that civil rights and liberties cases, split decisions, and the ideological direction of a dissenting opinion affected Justice Ginsburg’s use of emotive language in her authored dissenting opinions but that there was not a critical inflection point of the year 2013 in terms of her use of emotive language in her authored dissents. Though this latter finding is not consistent with our first hypothesis, Ginsburg’s consistency in her writing on her judicial philosophy, especially with regard to the purpose of dissenting opinions and collegiality on the Court, offers some perspective on why there was such stability in her use of emotive language across her tenure (Ginsburg 1992, 2010; Barnhart et al. 2004). We find evidence that Justice Ginsburg used more emotive language in her authored dissenting opinions for civil rights and liberties cases. Additionally, we find Justice Ginsburg used more emotive language when the majority opinion was ideologically conservative. In other words, Justice Ginsburg’s ideologically liberal dissenting opinions contained more emotional language than conservative dissenting opinions. Both of these findings are conceptually consistent with the literature given that more civil rights and liberties cases often speak to a larger external audience and that Ginsburg’s ideologically liberal dissenting opinions garnered closer attention from her largely liberal external audience (Corley 2008; Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck 2000; Krewson 2019; Johnson et al. 2019; Lewis and Rose 2014; Unah and Hancock 2006).

There are two limitations to our study. Though this study naturally limits the tendency to overgeneralize, given its narrow scope to Ginsburg’s authored dissents, we do not test for whether the justice composition of the majority coalition and the majority opinion writer affect the emotional tone of Ginsburg’s dissents. For instance, perhaps there is a statistically significant difference between the emotional tone of Ginsburg’s authored dissenting opinions when she was joined by a given justice, or combination of justices, in her dissent compared to another combination of justices. Likewise, this study does not examine if there is a statistically significant difference between the emotional tone of her dissenting opinions in relation to the majority opinion author. However, we suggest a natural continuation of this study would be to investigate whether the emotional language of Ginsburg’s dissenting opinions changed in relation to the majority opinion author and whether she used more emotive language in dissenting opinions she read from the bench. For example, did Ginsburg use stronger emotive language in her dissents to majority opinions written by Justice Antonin Scalia than in those authored by Chief Justice John Roberts? Or did she use stronger emotive language in her dissenting opinions that rebuke the majority opinions of a justice in the liberal bloc, like Justice Sonia Sotomayor or Justice Stephen Breyer? Answering these questions, among others related to Justice Ginsburg’s implicit interactions with other members of the Court through the language of her decisions, would be a compelling avenue for future study that could illuminate relationships between the Court and judicial behavior more generally.

Expanding the study of justices’ use of language using LIWC software beyond Justice Ginsburg herself could also be helpful in understanding the internal dynamics of given Court compositions and individual justices over time. For example, future research could examine the opinion writing, both majority and dissenting opinions, of members of the Warren Court, the Burger Court, the Rehnquist Court, or the Roberts Court to better understand Court dynamics during continuous periods of membership stability or how a given justice’s (or justices’) use of language changes in relation to internal or external stimuli like the addition of a new justice or a particular political or social event. Additionally, it could be fruitful to use the LIWC software to understand differences in emotional tone, authenticity, or analytic quality of conservative justices compared to liberal justices (or simply those dissenting or majority opinions that ideologically lean in one direction or the other, given that this study and others demonstrate that nominally liberal justices do author ideologically conservative dissenting opinions and vice versa). By better understanding trends in the language of opinions from justices of each ideological bloc, one could understand in a different light the changing trends in how justices from each group have operated over the decades to achieve their strategic goals.

Learning Activity

This chapter examines Justice Ginsburg’s use of emotional language in her dissenting opinions over her career in the US Supreme Court.

Break students into groups and have them review the “LIWC-22 Language Dimensions and Reliability,” which can be found in table 2 of the LIWC-22 Development Manual (11–12) (https://www.liwc.app/static/documents/LIWC-22 Manual – Development and Psychometrics.pdf).

Based on the language dimensions presented in table 2 of the LIWC-22 Development Manual, what other possible language dimensions could be used to analyze judicial texts? What was the reasoning for picking those dimensions?

Next, students should work together to develop a research question that would utilize LIWC as a means to analyze judicial behavior. The conclusion of this study offered several potential research questions that students may develop further (or they may come up with their own research questions). For instance, students may consider the dynamics of opinion language on the Court during continuous periods of unchanging membership, comparing a justice’s language in majority, concurring, and dissenting opinions; the influence of ideology on opinion language; how a justice’s gender and race influence language usage; whether a justice’s writing style and tone change based issue area; or the analytic quality of a single justice over their career or period of interest to name a few. Students are encouraged to look beyond the US Supreme Court and even beyond the proposed ideas listed above if a given topic piques their interest.

After developing a research question, students should consult existing scholarship and craft or outline a research proposal based on the research question.

Discussion

Students should be prepared to articulate the following during the class discussion: (1) Why did you choose your research question? (2) Why does it merit investigation? (3) Does it fill a gap in the existing scholarship? (4) What data is needed to carry out the study? (5) What could we learn from the proposed research?

References

Barnhart, Rebecca L., and Deborah Zalesne. 2004. “Twin Pillars of Judicial Philosophy: The Impact of the Ginsburg Collegiality and Gender Discrimination Principles on Her Separate Opinions Involving Gender Discrimination.” New York City Law Review 7 (2): 275–314.

Baum, Lawrence. 2006. Judges and Their Audiences: A Perspective on Judicial Behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bell, Courtney M., Phillip M. McCarthy, and Danielle S. McNamara. 2006. “Variations in Language Use across Biological versus Sociological Theories.” Manuscript, Institute for Intelligent Systems, University of Memphis.

Black, Ryan C., Matthew E. K. Hall, Ryan J. Owens, and Eve M. Ringsmuth. 2016. “The Role of Emotional Language in Briefs before the US Supreme Court.” Journal of Law and Courts 4 (2): 377–407.

Black, Ryan C., Timothy R. Johnson, and Justin Wedeking. 2012. Oral Arguments and Coalition Formation on the US Supreme Court: A Deliberate Dialogue. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Black, Ryan C., and Ryan J. Owens. 2012. “Supreme Court Agenda Setting: Policy Uncertainty and Legal Considerations.” In New Directions in Judicial Politics, edited by Kevin McGuire, 144–66. New York: Routledge.

Black, Ryan C., Ryan J. Owens, Justin Wedeking, and Patrick C. Wohlfarth. 2016. “The Influence of Public Sentiment on Supreme Court Opinion Clarity.” Law & Society Review 50(3): 703–32.

Bowie, Jennifer, and Elisha Carol Savchak. 2022. “State Court Influence on US Supreme Court Opinions.” Journal of Law and Courts 10 (1): 139–65.

Brennan, William, Jr. 1986. “In Defense of Dissents.” Hastings Law Journal 37 (3): 427–38.

Bryan, Amanda, and Eve Ringsmuth. 2016. “Jeremiad or Weapon of Words? The Power of Emotive Language in Supreme Court Dissents.” Journal of Law and Courts 4(1): 159–85.

Butler, Judith. 1999. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Canelo, Kayla S. 2022. “The Supreme Court, Ideology, and the Decision to Cite or Borrow from Amicus Curiae Briefs.” American Politics Research 50 (2): 255–64.

Carlson, Keith, Michael A. Livermore, and Daniel Rockmore. 2015. “A Quantitative Analysis of Writing Style on the US Supreme Court.” Washington University Law Review 93 (6): 1461–510.

Casillas, Christopher J., Peter K. Enns, and Patrick K. Wohlfarth. 2011. “How Public Opinion Constrains the US Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (1): 74–88.

Chaplin, Tara M. 2015. “Gender and Emotion Expression: A Developmental Contextual Perspective.” Emotion Review 7 (1): 14–21.

Corley, Pamela C. 2008. “The Supreme Court and Opinion Content: The Influence of Party Briefs.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (3): 468–78.

Corley, Pamela C., Paul M. Collins, and Bryan Calvin. 2011. “Lower Court Influence on US Supreme Court Opinion Content.” The Journal of Politics 73 (1): 31–44.

Corley, Pamela C., and Justin Wedeking. 2014. “The (Dis)Advantage of Certainty: The Importance of Certainty in Language.” Law & Society Review 48 (1): 35–62.

Epstein, Lee, and Tonja Jacobi. 2010. “The Strategic Analysis of Judicial Decisions.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 6 (1): 341–58.

Epstein, Lee, and Jack Knight. 1997. The Choices Justices Make. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Epstein, Lee, and Jeffrey A. Segal. 2000. “Measuring Issue Salience.” American Journal of Political Science 44 (1): 66–83.

Garoupa, Nuno, and Tom Ginsburg. 2009. “Judicial Audiences and Reputation: Perspectives from Comparative Law.” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 47: 451–90.

Ginsburg, Ruth Bader. 1992. “Speaking in a Judicial Voice.” New York University Law Review 67 (6): 1185–209.

Ginsburg, Ruth Bader. 2010. “The Role of Dissenting Opinions.” Minnesota Law Review 95 (1): 1–8.

Gleason, Shane A. 2020. “Beyond Mere Presence: Gender Norms in Oral Arguments at the US Supreme Court.” Political Research Quarterly 73 (3): 596–608.

Gleason, Shane A., Jennifer J. Jones, and Jessica Rae McBean. 2019. “The Role of Gender Norms in Judicial Decision-Making at the US Supreme Court: The Case of Male & Female Justices.” American Politics Research 47 (3): 494–529.

Gleason, Shane A., and EmiLee Smart. 2023. “You Think; Therefore I Am: Gender Schemas & Context in Oral Arguments at the Supreme Court, 1979–2016.” Political Research Quarterly 76 (1): 143–47.

Guinier, Lani. 2015. “Justice Ginsburg: Demosprudence through Dissent.” In The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, edited by Scott Dodson. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hazelton, Morgan L. W., and Rachael K. Hinkle. 2022. Persuading the Supreme Court: The Significance of Briefs in Judicial Decision-Making. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Hazelton, Vincent, William R. Cupach, and Jo Liska. 1986. “Message Style: An Investigation of the Perceived Characteristics of Persuasive Messages.” Journal of Social Behavior & Personality 1 (4): 565–74.

Hinkle, Rachael K. 2017. “Panel Assignment and Opinion Crafting in the US Courts of Appeals.” Journal of Law and Courts 5 (2): 313–36.

Hume, Robert J. 2009. How the Courts Impact Federal Administrative Behavior. New York: Routledge.

Johnson, Timothy R. 2004. Oral Arguments and Decision Making on the United States Supreme Court. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Johnson, Timothy R., Ryan C. Black, and Eve M. Ringsmuth. 2009. “Hear Me Roar: What Provokes Supreme Court Justices to Dissent from the Bench?” Minnesota Law Review 93: 1560–81.

Johnson, Timothy R., Paul J. Wahlbeck, and James F. Spriggs II. 2006. “The Influence of Oral Argument on the US Supreme Court.” American Political Science Review 100 (1): 99–113.

Jones, Jennifer J. 2016. “Talk ‘Like a Man’: The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992–2013.” Perspectives on Politics 14 (3): 625–42.

Kahn, Jeffrey H., Renee M. Tobin, Audra E. Massey, and Jennifer A. Anderson. 2007. “Measuring Emotional Expression with the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count.” American Journal of Psychology 120 (2): 263–86.

Krewson, Christopher N. 2019. “Strategic Sensationalism: Why Justices Use Emotional Appeals in Supreme Court Opinions.” Justice System Journal 40 (4): 319–36.

Lewis, David, and Roger P. Rose. 2014. “Case Salience and the Attitudinal Model: An Analysis of Ordered and Unanimous Votes on the Rehnquist Court.” Justice System Journal 35 (1): 27–44.

Maltzman, Forrest, James F. Spriggs, and Paul J. Wahlbeck. 2000. Crafting Law on the Supreme Court: The Collegial Game. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Massaro, Toni M. 1989. “Empathy, Legal Storytelling, and the Rule of Law: New Words, Old Wounds?” University of Michigan Law Review 87 (8): 2099–127.

Mulac, Antony, Howard Giles, James J. Bradac, and Nicholas A. Palomares. 2013. “The Gender-Linked Language Effect: An Empirical Test of a General Process Model.” Language Sciences 38: 22–31.

Murphy, Walter F. 1964. Elements of Judicial Strategy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Newman, Matthew L., Carla J. Groom, Lori D. Handelman, and James W. Pennebaker. 2008. “Gender Differences in Language Use: An Analysis of 14,000 Text Samples.” Discourse Process 45 (3): 211–36.

Niederhoffer, Kate G., and James W. Pennebaker. 2009. “Sharing One’s Story: On the Benefits of Writing or Talking about Emotional Experience.” In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, edited by Shane J. Lopez and C. R. Snyder, 621–32. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Owens, Ryan J., and Justin Wedeking. 2011. “Justices and Legal Clarity: Analyzing the Complexity of US Supreme Court Opinions.” Law & Society Review 45 (4): 1027–61.

Owens, Ryan J., Justin Wedeking, and Patrick C. Wohlfarth. 2013. “How the Supreme Court Alters Opinion Language to Evade Congressional Review.” Journal of Law and Courts 1: 35–59.

Pennebaker, J. W. 2011. The Secret Life of Pronouns: What Our Words Say about Us. New York: Bloomsbury.

Pennebaker, J. W., Ryan L. Boyd, Kayla Jordan, and Kate Blackburn. 2015. The Development of Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015. Austin: University of Texas at Austin.

Pennebaker, J. W., and L. A. King. 1999. “Linguistic Styles: Language Use as an Individual Difference.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (6): 1296–312.

Peterson, Steven A. 1981. “Dissent in American Courts.” The Journal of Politics 43 (2): 412–34.

Rice, Douglas, and Christopher Zorn. 2016. “Troll-in-Chief? Affective Opinion Content and the Influence of the Chief Justice.” In The Chief Justice: Appointment and Influence, edited by David J. Danelski and Artemus Ward, 306–29. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ringsmuth, Eve M., Amanda C. Bryan, and Timothy R. Johnson. 2013. “Voting Fluidity and Oral Argument on the US Supreme Court.” Political Research Quarterly 66 (2): 429–40.

Rosen, Jeffrey. 2019. Conversations with RBG: Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Life, Love, Liberty, and Law. New York: Henry Holt.

Savchak, Elisha Carol, and Jennifer Bowie. 2016. “A Bottom-Up Account of State Supreme Court Opinion Writing.” Justice System Journal 37 (2): 94–114.

Scalia, Antonin, and Bryan A. Garner. 2008. Making Your Case: The Art of Persuading Judges. St. Paul, MN: Thomson.

Schwartz, H. Andrew, Johannes C. Eichstaedt, Margaret L. Kern, Lukasz Dziurzynski, Stephanie M. Ramones, Megha Agrawal, Achal Shah, et al. 2013. “Personality, Gender, and Age in the Language of Social Media: The Open-Vocabulary Approach.” PLOS One 8 (9): 1–16.

Segal, Jeffrey A., and Harold Spaeth. 2002. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shapiro, David L. 2004. “Justice Ginsburg’s First Decade: Some Thoughts About Her Contributions in the Fields of Procedure and Jurisdiction.” Columbia Law Review 104 (1): 21–31.

Slobogin, Christopher. 2009. “Justice Ginsburg’s Gradualism in Criminal Procedure.” Ohio State Law Journal 70 (4): 867–88.

Sniezek, Janet A., and Timothy Buckley. 1995. “Cueing and Cognitive Conflict in Judge-Advisor Decision Making.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 62 (2): 159–74.

Spaeth, Harold J., Lee Epstein, Andrew D. Martin, Jeffrey A. Segal, Theodore J. Ruger, and Sara C. Benesh. 2022. Supreme Court Database, Version 2022. Release 01. http://supremecourtdatabase.org.

Tausczik, Yla R., and James W. Pennebaker. 2010. “The Psychological Meaning of Words: LIWC and Computerized Text Analysis Methods.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 29 (1): 24–54.

Unah, Issac, and Ange-Marie Hancock. 2006. “US Supreme Court Decision Making, Case Salience, and the Attitudinal Model.” Law & Policy 28 (3): 295–320.

Wedeking, Justin, and Michael A. Zilis. 2018. “Disagreeable Rhetoric and the Prospect of Public Opposition: Opinion Moderation on the US Supreme Court.” Political Research Quarterly 71 (2): 380–94.

Yip, Elijah, and Eric K. Yamamoto. 1998. “Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Jurisprudence of Process and Procedure.” Hawai‘i Law Review 20 (2): 647–98.

Zorn, Christopher, and Jennifer Bowie. 2010. “An Empirical Analysis of Hierarchy Effects in Judicial Decision Making.” The Journal of Politics 72 (4): 1212–21.

- Little Sisters of the Poor Saints Peter and Paul v. Pennsylvania (2020) 140 S. Ct. 2367, 2400. ↵

- In a 1996 speech, Justice Ginsburg explained her once private life had become public (Rosen 2019). She described in this speech, “Now trivial things are noticed,” and soon after her confirmation hearing, she “made the Style page of the New York Times and People magazine list of America’s Worst Dressed” (Rosen 2019, 130–31). However, this early public attention was minor compared to how her celebrity status took off in 2013 with the creation of the Tumblr blog. ↵

- It is worth noting that salience and civil rights and liberties issues correlate at just .322. Thus, there are no concerns about multicollinearity. ↵

- Because we recognize that even when a justice dissents, the dissenting opinion may be ideologically aligned with the ideological direction of the majority decision. However, in our data, all of Justice Ginsburg’s dissents were ideologically unaligned with the majority opinion. For instance, if the majority decision was ideologically conservative, Justice Ginsburg’s dissent was liberal and vice versa. ↵

- We also ran our model excluding civil rights and liberties, and the results did not change. ↵