Media

15 Co-Opting the Court

Partisan Actors, Mobilization, and the Supreme Court on Social Meda

Levi Bankston and Marcy Shieh

Introduction

Many political observers viewed Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination and confirmation in 2018 as a high-water mark of Supreme Court politicization in the United States (Gelman 2021; Krewson and Schroedel 2020). His confirmation was the continuation of a bitter fight between Democrats and Republicans over who gets to be one of the nine justices that sit on the Court. The fight began in 2016 after the unexpected death of Associate Justice Antonin Scalia. The Obama administration nominated Merrick Garland, and the Republican-controlled Senate refused to hold confirmation hearings. When Democrats lost the White House in 2016, the Trump administration quickly nominated conservative Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. And the Senate, still in Republican hands, then voted largely along partisan lines to first end the filibuster, a tradition of requiring 60 votes to confirm Supreme Court justices and then again to confirm Gorsuch by a vote of 54 to 45.

The battle over the Supreme Court intensified after Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy, the Court’s ideological median and swing vote, retired in June 2018 in the lead-up to the midterm elections. In his place, the Trump administration nominated conservative Brett Kavanaugh to fill the open seat. The Democratic minority in the closely divided Senate immediately declared united opposition against Trump’s nominee and attempted to delay the confirmation. Following the first confirmation hearing, sexual assault allegations made by Christine Blasey Ford against Kavanaugh became public, which eventually led the Senate Judiciary Committee in charge of the proceedings to hold additional hearings where both Ford and Kavanaugh testified. After the second set of hearings, the Senate then voted to confirm Kavanaugh as the 102nd associate justice of the Supreme Court on a narrow partisan vote of 50–48, ultimately shifting the ideological makeup of the Court in a conservative direction ahead of the 2018 midterm elections.

This chapter examines the extent to which the partisan conflicts within the walls of Congress have spilled over into the broader public by examining social media advertising related to Kavanaugh’s confirmation. As the lead-up and outcome of his confirmation illustrate, the contemporary confirmation process in the Senate is an intense partisan confrontation over the fate of the Supreme Court (Epstein et al. 2006). Today, both politicians and the public place high importance on the perceived partisan leanings of potential justices (Owens et al. 2014; Primo, Binder, and Maltzman 2008; Sen 2017; Shipan and Shannon 2003). Yet few studies have investigated how political actors choose to engage with the public about the future of the Supreme Court in a digital media environment (Vining 2011). The rise of interest groups has only accentuated the partisan mindsets of politicians and the public. In fact, interest groups–funded partisan messaging has become as potent as ever. While interest groups still leverage more traditional modes, such as television advertisements, to advocate their positions, they have no doubt established a stronghold on social media as well (Chadwick 2007; Fowler et al. 2021; West 2017). With over 220 million people in the US on Facebook, social media has become integral to the promotion of and exposure to various causes.

Analyzing approximately 50,000 political Facebook ads purchased between Kavanaugh’s nomination and midterm election day after his confirmation, we find that the groups behind these ads were largely partisan actors that included not only interest groups but also candidates and parties. These groups sent messages that emphasized the partisan implications of Kavanaugh’s polarizing confirmation and attempted to encourage the American public to donate money, contact their member of Congress, vote, and volunteer. They timed their mobilization appeals to correspond with the most salient moments during the confirmation process and were strategically tailored for and targeted at individuals perceived as most likely to respond to such appeals. In turn, our results suggest that a broad set of partisan actors seized on the saliency of Kavanaugh’s confirmation and leveraged the efficiency and targeting capacity of social media to mobilize supporters with divisive messaging.

We see the implications of our study as twofold. On the one hand, these actors may play a potential role in increasing both political engagement and even knowledge about the Court. Yet on the other hand, they have the potential to threaten the institution’s legitimacy in the eyes of the public. Without the public’s approval, the Court’s decisions risk social and political irrelevance and mass noncompliance.

Literature Review and Expectations

Article II, Section 2 of the US Constitution gives the president the authority to nominate individuals to serve as Supreme Court justices with the “advice and consent” of the Senate. For much of American history, the Senate approved of the president’s pick without much public pushback. The Senate Judiciary Committee in charge of reviewing nominees typically conducted brief, low-key hearings that garnered little outside attention or news coverage. With few exceptions, confirmation votes in front of the full Senate resulted in wide margins in favor of the president’s nominee and included support from senators of both parties (Epstein and Segal 2005).

Gone are the days of bipartisan support for judicial nominees and presidential deference where the Senate would accept whoever the president nominated (Binder and Maltzman 2002; Johnson and Roberts 2004). Over the past few decades, senators voting to confirm the president’s judicial nominees have placed greater and greater importance on the politics and ideology of potential federal judges (Cameron, Cover, and, Segal 1990; Epstein, Lindstädt, Segal, and Westerland 2006) as the Democratic and Republican Parties have become ideologically cohesive and polarized on many political issues (Abramowitz 2011; Abramowitz, Alexander, and Gunning 2006; Fiorina and Abrams 2012; Levendusky 2009). The American public likewise now considers who sits on the Supreme Court to be of political importance (Badas and Simas 2022; Kastellec, Lax, and Phillips 2010; Lane and Schoenherr 2019). For instance, in the 2018 election, 64% of voters listed Kavanaugh’s recent confirmation as an extremely or very important issue facing the country (Gallup 2018), and approval of the associate justice fell almost entirely along partisan lines (Marquette 2018). Other studies echo these findings of Supreme Court politicization by demonstrating the public’s reliance on partisan cues to determine support for a nominee (Armaly 2020; Sen 2017).

Existing research investigating the connection between Supreme Court nominations and public appeals has focused on interest groups and their mobilization activities. These investigations include, for example, examining the advertising, direct mail, and email crafted by interest groups during specific confirmations (Cameron, Gray, Kastellec, and Park 2020; Gibson and Caldeira 2009a; O’Connor, Yannus, and Patterson 2007; Vining 2011). Interest groups engage in these activities to influence governmental decisions and advocate for their preferred policy goals. During the confirmation proceedings, they often encourage their supporters to take action—for example, by contacting senators in support of or opposition to the nominee (Caldeira and Wright 1998; Vining 2011). Interest groups assume that senators care about public opinion and hope that their efforts will affect confirmation votes (Caldeira, Hojnacki, and Wright 2000; Kastellec, Lax, and Phillips 2010). An additional goal of these interest groups is organizational maintenance (Solberg and Waltenburg 2006). Interest groups capitalize on the public attention paid to the Supreme Court confirmation process to “demonstrate that they are active, recruit new members, and raise funds” (Vining 2011). Most existing literature has focused on formal interest groups’ attempts to mobilize the public in response to Supreme Court nominations. These investigations include, for example, examining the advertising, direct mail, and email crafted by interest groups during specific confirmations (Cameron, Gray, Kastellec, and Park 2020; Gibson and Caldeira 2009a; O’Connor, Yannus, and Patterson 2007; Vining 2011).

When interest groups get involved in confirmations, the content of their public appeals generally depends on support for the nominee (Caldeira and Wright 1998). Supportive interest groups typically leverage the public’s desire for an independent legal institution outside of “politics as usual.” For instance, interest groups and nominating presidents often engage in “crafted talk” and emphasize judicial nominees’ professional qualifications and positive personal qualities rather than their ideological commitments (Caldeira and Wright 1998; Cameron and Park 2011; Jacobs and Shapiro 2000). In contrast, interest groups who oppose the nominee are the most vocal critics, often highlighting the political consequences of their nominations (Caldeira and Wright 1998; Cameron et al. 2020).

Interest groups also strategically time their mobilization efforts to correspond with critical moments during the confirmation process (Wright 1996). Supreme Court confirmations are drawn-out processes occurring over several months. The public pays more attention to the later stages of the confirmation process and especially to Senate confirmation hearings and nominee testimony in the lead-up to the floor vote (Cameron, Gray, Kastellec, and Park 2020; Collins and Ringhand 2016; Collins and Ringhand 2013; Gibson and Caldeira 2009a). Despite more public attention during public hearings, however, recent confirmations have seen the bulk of interest activity occur prior to the confirmation hearing (Cameron, Gray, Kastellec, and Park 2020). One explanation is that interest groups seek to raise funds early on to pay for later grassroots efforts and lobbying activity (Shapiro 1989), yet evidence for this hypothesis is mixed (Vining 2011).

Most relevant to our investigation into online advertising during Kavanaugh’s confirmation proceedings is the Vining (2011) study examining interest group emails related to President George W. Bush’s three Supreme Court nominees. To our knowledge, his study is the only one to date discussing the implications of interest group activity related to the Supreme Court on digital media. The Vining (2011) study focuses on two different types of mobilization: to either act (i.e., contact senators) or contribute (i.e., donate money to candidates or organizations). He argues that email is an ideal communication channel to encourage supporters to act or donate money because individuals have self-selected to subscribe and receive interest group emails. Vining uncovers that the content of email appeals depends on the characteristics and goals of the particular interest group that sent them and corresponds to the timing of the nomination process. For instance, he finds that groups unsupportive of the nominee are more likely to make calls for action, while supportive groups take advantage of the increased attention to the Supreme Court to raise money for their organizations. And the frequency of email solicitations for donations increases at important milestones during the confirmation process, especially early on when the nominee is considered by the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Building on Vining (2011) and considering the capacity of social media, we examine the characteristics, messaging, timing, and targets of Facebook ads purchased by political groups during Kavanaugh’s confirmation. We suspect that a broader set of partisan political actors, beyond formal interest groups, purchased social media advertising during Kavanaugh’s confirmation process. First, social media platforms like Facebook lower the costs of ad production and delivery in comparison to other forms of outreach such as television (Fowler et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2018), enabling less well-funded political groups to engage in digital mobilization efforts. Second, the fight over Kavanaugh’s confirmation was hyperpartisan even before the allegations of sexual assault against him became public (Gelman 2020). Divided along party lines, the debate surrounding Kavanaugh was a prime opportunity for political parties, partisan politicians, and other Republican- and Democratic-leaning organizations to take a position on the nominee and solicit financial contributions from the public.

We expect that the content of social media ads should go beyond the sexual assault allegations to include politicized messaging on many partisan issues, such as abortion. While traditional models of mobilization argue the primary role of political actors in confirmations is to resolve uncertainty about how the nominee will behave on the Court (Caldeira and Wright 1998), the growing trend in ideological vetting of nominees suggests that both senators and the public are much more confident in how the nominee will vote in future cases. With uncertainty over confirmation votes largely resolved, political actors should shift their focus from predicting nominee behavior to concentrating on the political implications of their confirmation. Specifically, we expect that calls for mobilization should focus their messages on the partisan implication of Kavanaugh’s confirmation rather than Ford’s allegations against him and highlight its consequences for divisive issues expected to come before the justices (Vining and Bitecofer 2023).

We also expect that the amount of advertising should correspond to critical junctures when actors perceive the public is paying the most attention. This expectation is based on both the low cost of producing and disseminating social media ads. While groups could hypothetically send their appeals at any time, we suspect that actors will leverage the widely watched hearings as opportunities to receive the highest return on their investment. Given that the confirmation hearings will dominate the news cycle, we expect calls for mobilization are more likely to occur between the confirmation hearings and the confirmation vote than at any other time.

Finally, we consider the targets of the social media ads related to Kavanaugh’s confirmation. Scholars have identified how groups rely on social media platforms as a low-cost option for mobilizing political engagement (Bimber, Flanagin, and Stohl 2012; Karpf 2010; Kreiss 2016). Moreover, scholars have also examined how social media have made it much easier for individuals to engage in politics (Bennett, Maton, and Kervin 2008; Bimber 2017; Bode 2017; Gil de Zúñiga, Jung, and Valenzuela 2012; Oser and Boulianne 2020). Individuals no longer must sign up for an email mailing list to receive digital appeals from political groups, a core component of the Vining (2011) study. Rather, political groups have access to an array of user characteristics to target their digital appeals at different groups of people. At the time of our investigation, Facebook permitted advertisers to specify “custom audiences” based on their own lists, and the platform also made an extensive array of targeting features available, including demographics, geographical information, media consumption, political profiles, and issue interests (Kim et al. 2018).

We expect that groups will target their messages at demographic groups they perceive to be most responsive to their messaging. We choose to investigate targeting directed at females. We make this decision due to the perceived importance of the sexual assault allegations—a matter that has historically impacted more women than men—against Kavanaugh as well as because women have a perceived connection to many issues expected to come before the Court, particularly abortion and the fate of Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). Moreover, members of Congress of both parties tied the Kavanaugh allegations to the #MeToo movement when discussing the confirmation on social media (Wright, Clark, and Evans 2021).

Data and Methods

Our data consist of all political Facebook ads that mention the word Kavanaugh purchased between Kavanaugh’s nomination on July 9, 2018, and midterm election day on November 6, 2018. We collected the data from the Facebook Ad Library application programming interface (API). In total, we have a dataset with 50,268 unique ads bought by 1,656 unique groups. These ads received 735 million views and cost $19 million. The data contain information about the group who purchased the ad, the content of their message, the timing of the ad, and the demographic composition of their intended targets. The group information includes the page’s display name, page identification number, and the purchaser of the ad.

Message content includes text, title, and the description of any link to an external website (if present). In our results, we combine all these message fields into a single-text unit of analysis. For example, in the End Citizens United Facebook ad in figure 1, we combine the text (“Brett Kavanaugh is UNFIT for the Supreme Court and should be removed immediately. His extreme record in favor of giving corporate special interests and megadonors more power risks even more serious political corruption. Add your name to demand the House impeach Brett Kavanaugh.”), the title (“Demand the House impeach Kavanaugh”), and the description (“He should not sit on the highest court in the country”) to analyze as one observation rather than three separate and unique units, since that would include all the text present in the ad.

For targeting, the Facebook data reports estimate state-level geographic, gender, and age information on the targets of these ads. Our targeting analyses focus on gender, measured as the proportion of females who were targeted by a given ad.[1] The Facebook advertising API also provides data on the cost of the ads and the approximate number of impressions that each ad received. Facebook defines an impression as the number of times an ad is on screen.[2]

We began our inquiry with an initial qualitative investigation. We used a random sample of unique messages to develop an appropriate group classification scheme. From the sample, we manually coded each group based on the type of organization and its apparent partisanship. We were then able to generalize our coding to evaluate partisanship as a five-type typology, which differentiates between official and likely partisanship. Official partisanship is when the organization is formally affiliated with the party. They are differentiated from the “extended party network,” which is composed of interest groups, media, and nonprofits (Koger, Masket, and Noel 2009). These unofficial or de facto partisan groups are what we code as “likely” partisan groups. The final categories include independent or unknown party affiliations. These groups are mostly news media and some issue advocacy organizations. In ambiguous cases, coders defaulted to “independent” rather than a “likely” partisan affiliation. In cases where coding for partisanship is inappropriate or unknown, coders classified the group as “unknown.”

To categorize group characteristics, we classified the groups into nine categories: candidate, party, PAC (political action committee), nonprofit, news, questionable news, movement, suspicious, or other. “Candidate” captures current federal, state, and municipal officeholders as well as individuals officially listed on the ballot. Groups are coded as “party” if they are official organs of the formal party organization (e.g., DCCC or RNC). “PACs” are groups that are required to report their contributions and spending to the Federal Election Committee (FEC) but are neither candidates nor parties, while “nonprofits” are organizations with official IRS tax-exempt status. Groups are coded as “news” if their primary function is to report politics and current events. If the news organization has questionable reporting practices or exhibits extreme bias in its reporting, we coded it as “questionable.” To verify each group, coders checked each database in the same order as presented: Ballotpedia (candidates and parties), FEC (FEC-registered groups/PACs), GuideStar (nonprofits), Media Bias/Fact Check (news, questionable news, and news with extreme bias). Groups not in any of these databases were then coded as either an unregistered movement, suspicious, or other.

We coded groups that do not fit these categories as either movement, suspicious, or other. “Movement” is a group that can be categorized as grassroots or “astroturf” because they are not formally registered in any way with either the FEC or the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). “Suspicious” groups, on the other hand, are groups that seem to have only existed during the confirmation and, at the time of coding, had vanished. We classified all remaining groups, which make up less than 5%, as “other.” These remaining groups include, for example, clothing companies, law firms, and authors.

Our qualitative investigation of the groups also revealed a striking similarity in the messaging of official partisan actors, such as candidates and parties, and other groups who do not officially have a party identification. Based on these qualitative findings, we additionally coded each group for whether it either is officially connected to the Democratic or Republican Party or has a “de facto” partisan identification. By “de facto” partisan identification, we are referring specifically to interest groups that have close ties to one party or the other. For example, Planned Parenthood is closely aligned with the Democratic Party, and the National Rifle Association (NRA) often endorses and supports Republican Party candidates. We classified a group as “Democratic” or “Republican” based on the descriptions on its official websites and compared those descriptions to the decision direction classification system used by the Supreme Court Database (Spaeth, Epstein, et al. 2023). We coded groups without clear partisanship as either “independent” or “other.”

To classify the content of each ad’s message, we started again with qualitative investigation to develop a list of potential categories. We then performed a more rigorous analysis of our text unit. We first examined the 1,000 most common words present in the text unit to generate relevant categories (Guo et al. 2016). Next, we drew a random subset of unique text units to generate more categories and populate them with appropriate terms (Conway 2006).[3] We then performed an initial keyword search and assessed the quality of the classification. Each author independently reviewed a random sample of the results and proposed additions and removals to the list of keywords. Finally, we performed an additional keyword search after making the edits.

The output of our keyword search is the classification of the ads’ messages into 10 categories: mobilization, sexual assault, news media, abortion, healthcare, guns, environment, immigration, civil rights, and education. The mobilization category captures a variety of political activities, including calls for contacting legislators, contributions, voting, volunteering, and attending events. The sexual assault category identifies ads that are related to the sexual assault allegations made by Christine Blasey Ford and other women. The remaining categories include keywords designed to identify messages about the issues of abortion, healthcare, gun rights or reform, environmental regulation, immigration, civil rights, and education.

Groups, Messaging, Timing, and Targeting

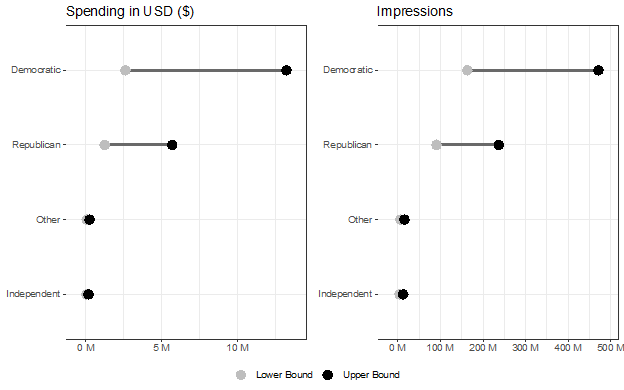

We find that the groups who bought Kavanaugh-related ads consist of a diverse set of official partisan and de facto partisan actors, including not only interest groups but also candidates and parties. In total, groups on Facebook spent between $4 and $19 million on ads related to Kavanaugh, which translates to between 260 and 735 million impressions. To situate these numbers, the total amount of television ad spending related to Kavanaugh’s nomination was $10,369,780 (Justice 2018). Even if we take the median value of these ranges at $11.5 million, the results suggest that groups on Facebook alone rivaled aggregate spending on television.

Figure 2 reveals that many of these groups are partisan actors with official and de facto relationships with both parties. Democratic groups spent approximately between $2.5 to $13.2 million between nomination and election day. Their Republican counterparts spent notably less, between $1.2 and $5.7 million. These ad buys generated between 163 and 471 million impressions for Democratic groups and between 91 and 237 million impressions for Republican groups. In contrast, the ads bought by groups coded “independent” or “other” composed around 1% of the overall spending and impressions.

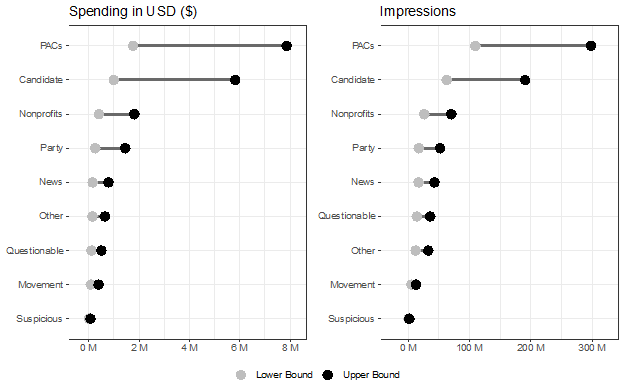

Figure 3 reveals the involvement of various political actors that went beyond interest groups. PACs make up the largest proportion, spending a combined $1.8 to $7.9 million in exchange for 109 to 298 million impressions. Similarly, candidates purchased between $1.0 million to $5.8 million in ads, resulting in 63 to 190 million impressions. If we combine the categories of PACs, nonprofits, and movements as an indicator of interest group activity, we see that interest groups were responsible for around 52% of the spending and impressions. Rivaling their spending were official partisan groups. Candidates and parties made up a combined 38% of the spending and received 33% of impressions.

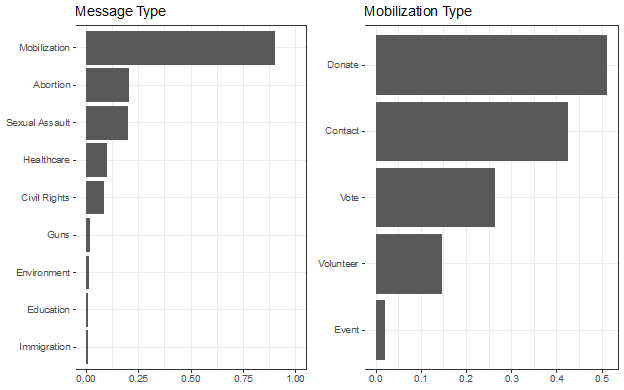

We expected that these groups would craft partisan and ideologically charged messages that would go beyond the allegations of sexual assault to include other issues. Figure 4 reveals these categories and the proportion of ads associated with each. The messages overwhelmingly include appeals for mobilization at 90% of all ads. Moreover, figure 4 reports a breakdown of these mobilization activities across different types of mobilization (i.e., contributions, contacting a legislator, voting, volunteering, and attending an event). More than half of the messages attempt to mobilize contributions and contact. However, these groups also mobilized other participation activities, such as voting, volunteering, and even attending events.

Figure 4 also reveals that ads go beyond allegations of sexual assault to include other partisan language and issues. The ads frequently employ partisan and ideological language at 30% of all ads, which is the second most frequent category. The prevalence of partisan language implies that groups highlighted the partisan implications of the confirmation. The ads also often mention the president and other candidates, which echoes the previous findings that these ads implicated a more diverse set of actors than just interest groups. The category that captures partisan language exceeds the proportion of messages classified into the sexual assault category, which is less than 20%. In addition, the category that identifies ads related to the allegations of sexual assault is roughly equivalent to the proportion of ads that mention the divisive issue of abortion. Furthermore, many ads mention a range of other partisan issues that had nothing to do with the sexual assault allegations, including healthcare, civil rights, environmental regulations, gun rights, education, and immigration.

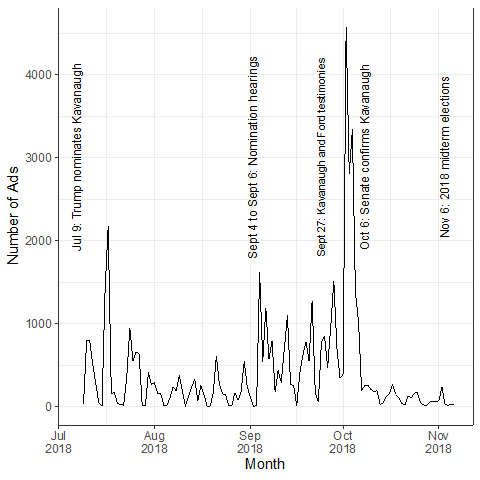

Next, we examined the timing of the social media ads across four phases of the confirmation process. The first phase took place from June 9, 2018, when President Trump first announced his nomination of Judge Kavanaugh, to September 7, 2018, when Kavanaugh had his initial nomination hearing. The second phase took place from September 8, 2018, to September 27, 2018, when both Kavanaugh and Ford testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee about the sexual assault allegations. The third phase is from September 28, 2018, to October 6, 2018, when the Senate voted 50–48 to confirm Kavanaugh. The final phase is from October 7, 2018, to November 6, 2018.

We expected that the amount of spending on social media would correspond to critical junctures during the confirmation process. In figure 5, we show that groups bought ads at critical junctures of Kavanaugh’s nomination process. In July, shortly following the nomination, groups on Facebook bought over 10,000 Kavanaugh-related ads. Groups continued to buy ads but at lower rates until a large surge in the number of ads following the hearings about the sexual assault allegations on September 27 and Kavanaugh’s confirmation on October 6. In this short 10-day period, groups purchased over 14,000 ads. Following the confirmation, groups purchased less than 6,000 ads in the lead-up to election day. The number of ads over time reveals that groups seized on the saliency of the events surrounding Kavanaugh’s confirmation, especially during the sexual assault hearings.

| Targeted gender | Average proportion of ads |

|---|---|

| Female | 0.5260231 |

| Male | 0.2643357 |

We expected that groups would target their ads at groups they perceive to be most responsive to their messaging, such as women. Table 1 shows that Facebook ads related to Kavanaugh overwhelmingly targeted women over men. In total, 46,431 ads related to Kavanaugh targeted a proportion of women. While targeting of gender groups is not as precise compared to the targeting of racial minorities or individuals who support specific issues, the evidence suggests political groups perceive that women care more about abortion than men, even if their attitudes on average do not differ from their male counterparts (Verba, Burns, and Schlozman 1997).

Discussion and Conclusion

Our analysis of over 50,000 Facebook ads related to Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court taps into the unique partisan landscape in the digital age. Seven out of 10 US adults use Facebook.[4] While these Facebook users tend to be women, are college educated, and skew younger, the number of adults over the age of 65 who use Facebook has increased by 20% since 2012.[5] With older adults, who tend to be more politically engaged, using Facebook, its influence in the political sphere is not going away anytime soon. Traditional forms of political campaigning may have always had an inherent partisan purpose, but the power of Facebook advertising comes from its precise ability to target and persuade specific users based on their core values and beliefs. In turn, political groups can leverage Facebook’s advertising tools to confirm the existing biases of specific users and convert them into supporters of their cause without the user taking the proactive step to receive messages.

We find that political groups took advantage of the highly contested Kavanaugh confirmation hearings to mobilize the public with partisan-fueled social media advertising. First, our results reveal that many partisan groups beyond traditional interest groups saw Kavanaugh’s confirmation as an opportunity to raise funds and encourage political participation. Second, their messaging was not limited to the sexual assault allegations that commanded public attention but instead expanded to include contentious issues that divide Republicans and Democrats. Third, we find that these partisan groups and actors timed their ads to correspond to moments during the confirmation process when the public was paying the most attention. Lastly, their divisive social media ads politicizing the Court were targeted disproportionately at women, likely because of their perceived responsiveness to sexual assault allegations and the fate of Roe v. Wade.

Our findings contribute to understanding how political actors and interest groups co-opt the Supreme Court to mobilize supporters. We recognize that Kavanaugh’s confirmation may be a high-water mark in Supreme Court saliency but argue it has implications outside of the most divisive judicial fight in recent memory. We expect that partisan actors should continue to seize on the saliency of the judicial branch whenever it becomes relevant. While we do not argue that the Supreme Court will become the perennial issue of American politics by any means, our argument is that when its saliency waxes, partisan actors should attempt to mobilize their supporters and highlight its ideological and partisan implications.

The implications of this kind of partisan mobilization related to the Supreme Court have both costs and benefits. First, when political actors provide partisan cues about the Supreme Court, they have the potential to increase the public’s knowledge about the institution and provide the public with additional opportunities to become engaged. The public has limited political knowledge and knows even less about the Supreme Court (Delli Carpini and Keeter 2002; Gibson and Caldeira 2009b). By focusing their advocacy and mobilization efforts on the Court whenever the public is paying attention, these actors have the potential to increase knowledge about the institution, increasing the number of people who know what role the institution plays in American politics and who sits on it. Likewise, the availability of these partisan cues, especially when linked to the Supreme Court, provides people information shortcuts that make participation in politics easier. Political groups on Facebook and other social media platforms, through their targeted messages, lower the barrier of entry and increase overall rates of participation by providing people with more opportunities to get involved.

The second implication of partisan mobilization linked to the Supreme Court concerns the institution’s legitimacy. The Supreme Court has long been “different” from the other branches of government. Even though the public may have a dual perception that the institution is both legal and political, the Court has maintained high and stable levels of support and legitimacy throughout its history (Caldeira and Gibson 1992; Gibson 2007; Gibson and Nelson 2014). Recent evidence suggests, however, that when political actors, especially copartisans, politicize the Court and highlight its partisan and ideological implications, it can threaten the institution’s legitimacy (Armaly 2018; Christenson and Glick 2015; Nelson and Gibson 2019). The fear is that if the Supreme Court is seen as part of “politics as usual,” faith in the institution will be undermined and leave the judicial branch open to structural changes or outright disregard for its rulings. It is worth reminding that the judiciary has the power of neither the “sword” nor the “purse,” as Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 78. As partisan actors continue to drag the court into politics, the public may begin to question the Court’s decisions.

Contentious fights over who sits on the Supreme Court have continued since Kavanaugh’s confirmation. On September 26, 2020, President Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett. Despite refusing to hold hearings for President Obama’s nominee for the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat in 2016 because President Obama was, at the time, “a lame-duck president,” the Republican majority pushed the Barrett confirmation through with a 52–48 vote right before the 2020 presidential election. Not a single Democrat voted for Barrett’s confirmation. On February 25, 2022, President Biden nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson to replace the retiring Justice Stephen Breyer. Jackson would become the first African American woman to sit on the Supreme Court. Once again, the Senate confirmed Jackson by a slim margin—a 53–47 vote—with only three Republicans voting with the Democrats.

Whether political groups politicizing the Supreme Court erodes its legitimacy in the eyes of the American remains an open question. What our evidence and subsequent confirmations make clear, however, is that divisive partisan fights over who sits on the bench will continue to take place not only on the Senate floor but also on social media.

Learning Activity

Instructions on How to Use the Meta Ad Library

These are the instructions as of August 12, 2023. The website content is subject to change.

- Go to the Meta Ad Library website (https://www.facebook.com/ads/library/?active_status=all&ad_type=political_and_issue_ads&country=US&media_type=all).

- Go to the “Search Ads” section.

- Click on the drop-down menu to the far left, which allows the selection of the region. Select “United States.” Note that there is a list of countries that you could select as well. If you would prefer not to specify a category, you could select “All.”

- Click on the second drop-down menu, which allows the selection of the ad category. Select “Issues, elections or politics.” Note that you can also select “Housing,” “Employment,” or “Credit.” If you would prefer not to specify a category, you could select “All ads.” You must make a drop-down selection to proceed.

- You may search using the following methods:

- Use the exact phrase: “Kavanaugh”

- Search for ads containing all these words but not necessarily in order: Kavanaugh | Roberts | Alito | Sotomayor | Kagan

- Click the “Enter” key on your keyboard.

- A page containing the results will load.

- The top of the page contains your search criteria, which you may edit.

- The right side of the top half of the page contains options you may apply to your search criteria.

- Here are the filters you can apply:

- Delivery by region (where people who saw the ads are located): You may select a state in the United States. Defaulted to “All Regions.”

- Language: You have the option of “All languages,” “English,” and “Spanish.” Defaulted to “All languages.”

- Advertiser: You may select “All advertisers” to view ads from every sponsor or the specific organization that sponsored the ad. Defaulted to “All advertisers.”

- Platform: You may select one of Meta’s platforms, such as “All Platforms,” “Facebook,” “Instagram,” “Audience Network,” and “Messenger.” Defaulted to “All Platforms.”

- Media type: You may select “All Media Type,” “Images (Images with Little to No Text),” “Memes (Images with Text: ‘[Search Term]’),” “Images and Memes,” “Videos (Keyword within Video Transcript of Ad Copy: ‘[Search Term]’),” and “No Image or Video.” Defaulted to “All Media Type.”

- Active status: You may select, “Active and Inactive,” “Active Ads,” and “Inactive Ads.” Active ads are ads that are still being displayed on members’ feeds; inactive ads were once displayed but are no longer displayed. Defaulted to “Active and Inactive,” which means the search results will include both old and current ads.

- Impressions by date: You may select a date range starting from May 7, 2018, to the present day. If you would like to choose an exact date, you may select or input the same date in both the “From” and “To” date boxes.

- Disclaimer: You may select “All Disclaimers” to view ads from every organization or individual that paid for the ad. Defaulted to “All Disclaimers.” Note that disclaimers do not have to be unique, so different organizations might share the same name.

- Estimated audience size: This metric uses the number of Account Center accounts that meet the criteria when advertisers select targeting options during the creation of the ad. You may select “All Estimated Audience Sizes,” “100–1K,” or “>1M.” Defaulted to “All Estimated Audience Sizes.”

- Clear all: You have the option to “Clear All,” which would erase all the filters you have added, or “Apply [Number] Filters,” which would show results that meet the criteria as indicated by the filters.

- Sort by: You can sort by the number of impressions (the number of eyeballs per ad) from “High to Low” or “Low to High.” You may also “Reset” (default) the order of impressions, which would show the ads from most recent to least recent.

- Save search: After you have set the filters, you may want to “Save” your particular search so you do not have to reselect the country and category, retype the search term, and re-add the filters. When you save the search, you may call the search whatever you want. You will be able to access the saved search again from two different locations:

- The front page: You may click on “Saved searches” to access your saved search terms and their associated filters. You can just click “Go” to access the search results.

- The results page also includes a “Saved searches” button on the top right of the page.

- Export CSV: You may output a CSV file based on your search results, which include variables related to the search parameters and fields in your search results. The list of variables is on the Ad Library API page (https://www.facebook.com/ads/library/api/?source=nav-header).

- The ads in the search results contain information on whether the ad is active or inactive, the time period the ad was active, the Meta platform the ad was on, the category associated with the ad, the estimated audience size, the amount spent, and the number range of impressions, the ad’s unique identifier, and the number of unique ads that contain the same textual and visual elements but may have been active during different time frames.

- For each completely unique ad, there is a button called “See ad details.”

- The “Ad details” page contains information on the right side of the page on the estimated audience size, the amount range spent by the advertisers, the number range of impressions, the age of gender breakdown of those who saw the ads, and the region/location of those who saw the ads.

- On the left side of the page, below the ad, is information about the advertiser. There is an option to see all the advertiser’s other ads on Meta. In addition, there is information on the advertiser’s Meta-related social media profiles; the number of followers on those profiles; the total spent by the advertiser, in particular ad categories; and the total spent by the advertiser, in particular ad categories in the past week.

- For each ad that shares creative and text components with a different ad that was active in a different time period, there is a button called “See summary details,” which provides summary information on the impact of that group of ads.

- The “Summary data” page contains information on the amount range spent by the advertisers, the number range of impressions, the age of gender breakdown of those who saw the ads, and the region/location of those who saw the ads.

Instructions for Class Activity

- Introduction: Complement the research article with the New York Times article by Matthew Rosenberg, “Ad Tool Facebook Built to Fight Disinformation Doesn’t Work as Advertised,” published in 2019.

- As they read the news article, ask them to note the advantages and disadvantages of the ad library.

- Demonstration: During class, conduct a live demonstration of Meta Ad Library. Show the class how to access it, ask students for suggestions as to what to search, and explore the available ad details, including the estimated audience size, the amount spent, and the number of impressions.

- Ask the class whether these metrics are sufficient and what improvements could be made to increase transparency.

- Research and exploration: Divide the class into small groups and assign each group a sitting US Supreme Court justice. Each group will explore the “Issues, elections or politics” ad category. Encourage them to explore different types of ads, including videos, images, and carousel ads.

- Request the class to search “healthcare” in the ad library search tool.

- Within each group, students should discuss with one another what they find effective and ineffective about advertising on Facebook. What kind of visual (e.g., images, videos) or textual (e.g., titles, descriptions) elements do advertisers use that help or hurt their overall message? When they discuss these elements, suggest that they refer to the engagement metrics to bolster their argument.

- Application: In addition to the analysis, the groups should create their own ads that include the name of the justice they were assigned. This activity could be done digitally or with a handout.

- Students must include the name of the group (the group may be real or fiction), the text elements (e.g., the main text of the ad, the title of the ad, and the description), and the visual elements (e.g., image or other types of multimedia). This is an opportunity for students to be creative and utilize images or videos.

- Students must create an ad with the following components:

- Group presentations: Have each group present its ads to the class.

- The first member of the group would introduce their group and the central goal of the ad. For example, is the ad trying to get people to donate money to a cause or sign a petition to impeach a justice?

- The second member of the group would discuss the ad’s target audience. Is there a particular region this ad would target? What age and gender brackets should view this ad? How long would the ad be active?

- The third member of the group would discuss the creative choices made in the ad and how the ad attempts to cater to its target demographics.

- Discussion: After each group has presented, the class could discuss how creating their own ads has changed how they might interact with ads on social media in the future.

- Suggested grading rubric: Out of 55 points.

- Ad components: Ensure that the ad has the correct structure.

- Main text (10 points)

- Title of the ad (5 points)

- Description of the ad (5 points)

- Main visual (image or video; 10 points)

- Group presentation: The group is able to articulate the rationale for including certain characteristics in the ad based on the ad’s goals and target audiences.

- Clarity of the ad’s goal (10 points)

- Clarity of target audiences (10 points)

- Region

- Age

- Gender

- Time period

- Innovation (5 points): Does the ad capture its intended audience’s attention?

- Ad components: Ensure that the ad has the correct structure.

References

Abramowitz, Alan I. 2011. “Expect confrontation, not compromise: The 112th House of Representatives is likely to be the most conservative and polarized house in the modern era.” PS, Political Science & Politics 44(2): 293.

Abramowitz, Alan I., Brad Alexander, and Matthew Gunning. 2006. “Incumbency, redistricting, and the decline of competition in US House elections.” The Journal of Politics 68(1): 75–88.

Armaly, Miles T. 2018. “Extra-judicial actor induced change in Supreme Court legitimacy.” Political Research Quarterly 71(3): 600–613.

Armaly, Miles T. 2021. “Loyalty over fairness: Acceptance of unfair supreme court procedures.” Political Research Quarterly, 74(4): 927–40.

Badas, Alex, and Elizabeth Simas. 2022. “The Supreme Court as an electoral issue: Evidence from three studies.” Political Science Research and Methods 10(1): 49–67.

Bennett, Sue, Karl Maton, and Lisa Kervin. 2008. “The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence.” British Journal of Educational Technology 39(5): 775–86.

Bimber, Bruce. 2017. “Three prompts for collective action in the context of digital media.” Political Communication 34(1): 6–20.

Bimber, Bruce, Andrew Flanagin, and Cynthia Stohl. 2012. Collective action in organizations: Interaction and engagement in an era of technological change. Cambridge University Press.

Binder, Sarah A., and Forrest Maltzman. 2002. “Senatorial delay in confirming federal judges, 1947–1998.” American Journal of Political Science 46(1): 190–99.

Bode, Leticia. 2017. “Gateway political behaviors: The frequency and consequences of low-cost political engagement on social media.” Social Media + Society 3(4): 1–10.

Brennan Center for Justice. 2018. “Follow the money: Tracking TV spending on the Kavanaugh nomination.” https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/follow-money-tracking-tv-spending-kavanaugh-nomination. Accessed February 19, 2020.

Caldeira, Gregory A., and J. L. Gibson. 1992. “The etiology of public support for the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 36(3): 635–64.

Caldeira, Gregory A., Marie Hojnacki, and John R. Wright. 2000. “The lobbying activities of organized interests in federal judicial nominations.” The Journal of Politics 62(1): 51–69.

Caldeira, Gregory A., and J. R. Wright. 1998. “Organized interests and agenda setting in the U.S. Supreme Court.” American Political Science Review 82(4): 1109–27.

Cameron, Charles M., A. D. Cover, and J. A. Segal. 1990. “Senate voting on Supreme Court nominees: A neoinstitutional model.” American Political Science Review 84(2): 525–34.

Cameron, Charles M., Cody Gray, Jonathan P. Kastellec, and Jee-Kwang Park. 2020. “From textbook pluralism to modern hyperpluralism: Interest groups and Supreme Court nominations, 1930–2017.” Journal of Law and Courts 8(2): 301–32.

Cameron, Charles, and Jee-Kwang Park. 2011. “Going public when opinion is contested: Evidence from presidents’ campaigns for Supreme Court nominees, 1930–2009.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 41(3): 442–70.

Chadwick, Andrew. 2007. “Digital network repertoires and organizational hybridity.” Political Communication 24(3): 283–301.

Christenson, Dino P., and David M. Glick. 2015. “Chief Justice Roberts’s health care decision disrobed: The microfoundations of the Supreme Court’s legitimacy.” American Journal of Political Science 59(2): 403–18.

Collins, Paul M., Jr., and Lori A. Ringhand. 2013. Supreme Court confirmation hearings and constitutional change. Cambridge University Press.

Collins, Paul M., Jr., and Lori A. Ringhand. 2016. “The institutionalization of Supreme Court confirmation hearings.” Law & Social Inquiry 41(1): 126–51.

Conway, Mike. 2006. “The subjective precision of computers: A methodological comparison with human coding in content analysis.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 83(1): 186–200.

Delli Carpini, Michael X., and Scott Keeter. 2003. “The internet and an informed citizenry.” In The civic web: Online politics and democratic values, edited by D. M. Anderson and M. Cornfield, 120–56. Rowman & Littlefield.

Epstein, Lee, René Lindstädt, Jeffrey A. Segal, and Chad Westerland. 2006. “The changing dynamics of Senate voting on Supreme Court nominees.” The Journal of Politics 68(2): 296–307.

Fiorina, Morris P., and Samuel J. Abrams. 2012. Disconnect: The breakdown of representation in American politics. University of Oklahoma Press.

Fowler, Erika Franklin, Michael M. Franz, Gregory J. Martin, Zachary Peskowitz, and Travis N. Ridout. 2020. “Political advertising online and offline.” American Political Science Review 115(1): 130–49.

Gallup. 2018. “Top issues for voters: Healthcare, economy, immigration.” https://news.gallup.com/poll/244367/top-issues-voters-healthcare-economy-immigration.aspx. Accessed February 20, 2020.

Gelman, Jeremy. 2020. “Partisan Intensity in Congress: Evidence from Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court Nomination.” Political Research Quarterly 74: 450–63.

Gelman, Jeremy. 2021. “Partisan intensity in Congress: Evidence from Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination.” Political Research Quarterly 74(2): 450–63.

Gibson, James L. 2007. “The legitimacy of the US Supreme Court in a polarized polity.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 4(3): 507–38.

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009a. Citizens, courts, and confirmations: Positivity theory and the judgments of the American people. Princeton University Press.

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009b. “Knowing the Supreme Court? A reconsideration of public ignorance of the high court.” The Journal of Politics 71(2): 429–41.

Gibson, James L., and Michael J. Nelson. 2014. “The legitimacy of the US Supreme Court: Conventional wisdoms and recent challenges thereto.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 10: 201–19.

Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Nakwon Jung, and Sebastián Valenzuela. 2012. “Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17(3): 319–36.

Guo, Lei, Chris J. Vargo, Zixuan Pan, Weicong Ding, and Prakash Ishwar. 2016. “Big social data analytics in journalism and mass communication: Comparing dictionary-based text analysis and unsupervised topic modeling.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 93(2): 332–59.

Jacobs, Lawrence R., and Robert Y. Shapiro. 2000. Politicians don’t pander: Political manipulation and the loss of democratic responsiveness. University of Chicago Press.

Johnson, Timothy R., and Jason M. Roberts. 2004. “Presidential capital and the Supreme Court confirmation process.” The Journal of Politics 66(3): 663–83.

Karpf, David. 2010. “Online political mobilization from the advocacy group’s perspective: Looking beyond clicktivism.” Policy & Internet 2(4): 7–41.

Kastellec, Jonathan P., Jeffrey R. Lax, and Justin H. Phillips. 2010. “Public opinion and Senate confirmation of Supreme Court nominees.” The Journal of Politics 72(3): 767–84.

Kim, Young Mie, Jordan Hsu, David Neiman, Colin Kou, Levi Bankston, Soo Yun Kim, Richard Heinrich, Robyn Baragwanath, and Garvesh Raskutti. 2018. “The stealth media? Groups and targets behind divisive issue campaigns on Facebook.” Political Communication 35(4): 515–41.

Koger, Gregory, Seth Masket, and Hans Noel. 2009. “Partisan webs: Information exchange and party networks.” British Journal of Political Science 39(3): 633–53.

Kreiss, Daniel. 2016. “Seizing the moment: The presidential campaigns’ use of Twitter during the 2012 electoral cycle.” New Media & Society 18(8): 1473–90.

Krewson, Christopher N., and Jean R. Schroedel. 2020. “Public views of the US Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Kavanaugh confirmation.” Social Science Quarterly 101(4): 1430–41.

Lane, Elizabeth A., and Jessica A. Schoenherr. 2019. “‘A matter of great importance’: Interest groups, the Senate judiciary committee, and Supreme Court confirmation hearings.” Arlen Specter Center Research Fellowship, paper 1. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/ascps_fellowship/1.

Levendusky, Matthew. 2009. The partisan sort: How liberals became democrats and conservatives became republicans. University of Chicago Press.

Marquette. 2018. “New Marquette Law School poll finds tight race for Wisconsin governor, Baldwin leading in Senate contest.” https://law.marquette.edu/poll/2018/10/10/mlsp49release/. Accessed January 26, 2021.

Nash, Jonathan Remy, and Joanna Shepherd. 2020. “Filibuster change and judicial appointments.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 17(4): 646–95.

Nelson, Michael J., and James L. Gibson. 2019. “How does hyperpoliticized rhetoric affect the US Supreme Court’s legitimacy?” The Journal of Politics 81(4): 1512–16.

O’Connor, Karen, Alixandra B. Yannus, and Linda Mancillas Patterson. 2007. “Where have all the interest groups gone? An analysis of interest group participation in presidential nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States.” In Interest Group Politics, edited by Alan J. Cigler and Burdett A. Loomis, 340–65. 7th ed. CQ Press.

Oser, Jennifer, and Shelley Boulianne. 2020. “Reinforcement effects between digital media use and political participation: A meta-analysis of repeated-wave panel data.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84(S1): 355–65.

Owens, Ryan J., Daniel E. Walters, Ryan C. Black, and Anthony Madonna. 2014. “Ideology, qualifications, and covert Senate obstruction of federal court nominations.” University of Illinois Law Review 2014(2): 347–88.

Primo, David M., Sarah A. Binder, and Forrest Maltzman. 2008. “Who consents? Competing pivots in federal judicial selection.” American Journal of Political Science 52(3): 471–89.

Sen, Maya. 2017. “How political signals affect public support for judicial nominations: Evidence from a conjoint experiment.” Political Research Quarterly 70(2): 374–93.

Shapiro, Martin M. 1990. “Interest groups and Supreme Court appointments.” Northwestern University Law Review 84: 935–61.

Shipan, Charles R., and Megan L. Shannon. 2003. “Delaying justice(s): A duration analysis of supreme court confirmations.” American Journal of Political Science 47(4): 654–68.

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Eric N. Waltenburg. 2006. “Why do interest groups engage the judiciary? Policy wishes and structural needs.” Social Science Quarterly 87(3): 558–72.

Spaeth, Harold, Lee Epstein, Ted Ruger, Sarah C. Benesh, Jeffrey Segal, and Andrew D. Martin. 2023. Supreme Court Database, Version 2023, Release 1. http://supremecourtdatabase.org.

Verba, Sidney, Nancy Burns, and Kay Lehman Schlozman. 1997. “Knowing and caring about politics: Gender and political engagement.” The Journal of Politics 59(4): 1051–72.

Vining, Richard L., Jr. 2011. “Grassroots mobilization in the digital age: Interest group response to Supreme Court nominees.” Political Research Quarterly 64(4): 790–802.

Vining, Richard L., Jr., and Rachel Bitecofer. 2023. “Change and continuity in citizens’ evaluations of Supreme Court nominees.” American Politics Research 51(1): 57–68.

West, Darrell M. 2017. Air wars: Television advertising and social media in election campaigns, 1952–2016. CQ Press.

Wright, Jamie M., Jennifer Hayes Clark, and Heather K. Evans. 2022. “‘They were laughing’: Congressional framing of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s sexual assault allegations on Twitter.” Political Research Quarterly 75(1): 147–59.

Wright, John R. 1996. Interest groups and Congress: Lobbying, contributions, and influence. Allyn & Bacon.

Appendix: Keywords

Abortion

abortion, antilife, antichoice, antiabortion, antilife, birth control, body, planned parenthood, prochoice, pro choice, pro life, prolife, reproduction, reproductive, roe, wade, womens rights

Civil Rights

adoption, african, civil rights, equality, glbt, human rights, lgbtq, lgbtq, lgbtqi, lgbtqia, marriage, religion, voting rights

Education

betsy, devos, school

Environment

climate, environment, fracking, warming, pollute

Guns

2nd amendment, arms, firearm, gun, national rifle association, nra, second amendment, weapon

Healthcare

aca, affordable care, health, healthcare, medicaid, medicare, obamacare, preexisting conditions, premiums, repeal and replace

Immigration

alien, asylum, border, daca, deferred action, deportation, dreamers, hispanic, ice, immigrant, immigration, invasion, mexico, migration, sanctuary

Mobilization

#bluewave, #redwave, ballot, block, blue, call, chip, contact, contribution, defend, donate, donor, elect, election, email, flood, grassroots, invitation, invite, meeting, message, mobilization, movement, name, november, petition, pledge, protest, rally, red, register, reject, rsvp, send, sign, stop, stopkavanaugh, support, tell, text, ticket, volunteer, vote

Sexual Assault

#believesurvivors, #metoo, accuse, accuser, allegation, assault, beer, believe, blasey, bush, calendar, christine, credibility, crime, damon, daughter, documents, drunk, fbi, ford, guilty, harassment, hearing, innocence, investigation, keg, misogyny, oath, rape, sexual, sexually, survivors, testimony, witness

- In the Facebook Ads Manager, groups can specify certain demographics they want to target, including gender. Groups can set which gender(s) they want to target as well as access more detailed targeting tools by specifying other demographic information, interests, and behaviors. Different criteria influence the proportion of men and women targeted. ↵

- Facebook provides both the amount spent and the number of impressions in intervals rather than exact numbers. Because we do not know the aggregate distribution of either measure, we provide both their lower and upper bounds in our descriptive results. ↵

- Keywords were selected to be unique enough to reliably classify a message to a category but not too unique that they miss a large portion of a message category. ↵

- https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/. ↵

- https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/06/01/facts-about-americans-and-facebook/. ↵