Decision Making

9 To Publish or Not Publish

Exploring Federal District Judges’ Published Decisions

Susan W. Johnson; Ronald Stidham; Kenneth L. Manning; and Robert A. Carp

The federal district courts are the trial courts in the federal judicial system. Their rulings are available to the public through the Federal Supplement, the official publication for the federal district courts. The Federal Supplement does not include all decisions of the federal district courts; rather, its volumes include only those cases that are deemed sufficiently important for publication by the federal district court judge presiding over the case. Since many researchers rely on published cases as their data source, it is important to understand the motivation federal district court judges have in selecting certain cases for publication. The Official Publication Guidelines of the US Judicial Conference outline criteria for publication; however, whether a case meets the criteria is at the discretion of the presiding judge. This study explores patterns of federal district decision publication to determine whether and the extent to which judges rely solely on the official publication criteria when publishing their decisions. Understanding why judges publish some decisions but not others may be helpful in elucidating the overall trial court decision-making process and understanding factors that motivate judicial processes and behavior.

Prior Research on the Federal District Courts and Publication

As the major trial courts in the federal system, the US District Courts “represent the basic point of input for the federal judiciary and are the ‘workhorses’ of the federal system” (Carp, Stidham, and Manning 2010, 14). Roughly 10 percent of all decisions rendered in the federal district courts are published (Vestal 1970; Rowland and Carp 1996; Songer 1988). This small percentage presents several questions. Are those cases selected for publication representative of all decisions rendered by the federal district courts? What are the factors that lead to their selection for publication?

Formally, published opinions in the Federal Supplement are those “which are of general precedential value” (Songer 1988, 206). Because the Federal Supplement only publishes “those decisions which the judges themselves (or their clerks) regard as inherently significant and worthy,” many scholars argue that decisions published in the Federal Supplement represent the major policy decisions of the federal district courts (Rowland and Carp 1996). In these cases, we expect judges to exhibit judicial discretion (Dolbeare 1969) and enact new legal policy. Published decisions are also important because practitioners suggest the Federal Supplement is the “means by which the opinions of the district courts are made available to the legal profession” (Vestal 1966, 74). Thus it seems reasonable that publication in the Federal Supplement is a good indicator of the policy business of the federal district courts for both researchers and practitioners.

However, other scholarship argues that without examining unpublished decisions of the federal district courts, researchers cannot be sure that published decisions are representative of the entire business of the federal district courts. Songer (1998) questions the sole use of published decisions in judicial behavior research, finding that “there are a substantial number of unpublished district court decisions which cannot be assumed to be trivial” (Songer 1988, 213). Despite this criticism, Rowland and Carp (1996) contend that published cases constitute a random sample of all district court decisions and are of significant precedential and policy-making value. It is important that researchers understand the factors that lead to publication in order for them to conclude that judicial behavior research based solely on published decisions is representative of the entire decision-making patterns of the federal courts. Again, only one or two out of ten federal district courts decisions are published (Swenson 2004). If unpublished decisions differ substantially from published decisions, this could indicate that judicial behavior research based only on published decisions might be skewed and not offer an accurate or complete picture of judicial behavior. Judicial scholarship research does not often include unpublished decisions; these decisions are harder to obtain and more numerous, thus more difficult to process. To the extent that these unpublished decisions establish new precedents or solve politically salient issues of law, their omission from judicial behavior research may result in incomplete results and reduce our understanding or create misunderstandings of the policy-making function of the federal district courts.

Uncovering the factors leading to publication may shed more light on the question of whether published opinions are indeed those that are likely to be of a policy-making nature. Several studies utilizing various approaches have attempted to uncover the overall publication patterns of federal district court judges’ opinions. In a study of opinion writing by federal district judges, Stidham and Carp (1999) find that publication rate per judge varies widely. Using data consisting of all published decisions from the Federal Supplement from 1933 to 1995, they found that of 1,589 judges, 25 had authored more than two hundred opinions over an average career spanning 23.5 years. They also found these judges tended to write more during the middle third of their careers, concluding that perhaps judges embark on a period of socialization during the first third of their careers, with greater propensity to publish written opinions as they gain more experience (Stidham and Carp 1999).

Other research suggests judge characteristics and workload affect publication. Taha (2001), analyzing a smaller sample of 188 decisions (55 published and 133 unpublished), finds that older judges, judges with political backgrounds, and those with higher ABA ratings are more likely to publish their decisions (Taha 2001). Taha (2001) also finds that higher caseloads result in lower publication rates but does not find evidence of judges publishing as a means of advertising for elevation to a higher-level appellate court. Similarly, a study of appellate court judges’ publication patterns finds they are not particularly strategic in their decision to publish (Law 2006).

Swenson (2004) finds that federal district court judges are more likely to publish when the case meets the criteria of the Official Publication Guidelines of the US Judicial Conference. Additionally, her research suggests that opinions are more likely to be published if powerful, well-placed litigants and their attorneys are parties to the suit. Swenson’s findings suggest that these powerful, “repeat player” litigants (Galanter 1974), who have more resources and are better equipped to litigate based on their frequent use of the legal system, may implement a long-term strategy of “playing for the rules” as opposed to winning their cases outright as a short-term strategy (Swenson 2004). These litigants, she concludes, “would wisely treat publication of favorable precedent as part of their strategy” (2004, 126). These repeat player litigants are also more likely to be involved in more salient cases, thus increasing the likelihood that decisions in their cases would be among those that are published.

Swenson also finds that federal district judges are more likely to publish if their judicial circuit emphasizes a culture of publication over nonpublication (Swenson 2004). In some circuits, publication norms may be stronger than in other circuits (Swenson 2004). In fact, studies show that publication rates vary from one circuit to another, ranging from 10 percent by district courts in some circuits to closer to 50 percent in others (Mckenna, Hooper, and Clark 2000). A regional culture exists in the circuits that carries over to the federal district courts. Rowland and Carp (1996) note that district courts in different circuits “follow important sectional lines that mark off historical, social, and political differences that give them a distinctly regional character” (1996, 96). Thus circuit publication norms may influence the frequency with which federal district court judges publish their opinions.

Beyond socialization and experience, other factors potentially influence federal district court judges’ publication decisions. Baum (1997) suggests that lower court judges concentrate on multiple goals simultaneously, unlike US Supreme Court justices who retain more discretion enabling them to focus solely on their policy-making goals. Such goals include career ambition for higher office, limiting their immense workloads, and addressing several audiences at once, such as the community in which they live and the legal profession. Thus it is plausible that a variety of factors could influence all facets of a federal district judge’s career activities, including which decisions they submit for publication in the Federal Supplement.

Federal district judges’ goals might also include maintaining professional reputations by following the official publication criteria. Baum (1997) suggests judges’ goals may extend beyond furthering their legal policy goals and include operative goals, such as maintaining personal standing with court audiences and good relations with other judges. Irrespective of policy goals, whether judges pursue such operative goals, such as following official publication criteria to maintain personal standing with their colleagues and others, remains an “open question” theoretically and empirically (1997, 55). Baum further explains, “Much of what judges do to enhance their standing with people who are important to them can be considered semiconscious. Judges may do various things to win the favor of legal scholars, for instance, without fully recognizing that this is what they are trying to accomplish” (1997, 12). Publishing decisions, either because it comports with norms or follows publication criteria, might then be a goal of federal district court judges. Promotion concerns might also be a motivation for maintaining professional reputations through consistently following circuit norms of publication and official criteria because it “is directly in the hands of federal officials” (Swenson 2004, 126).

Federal district court judges have a higher probability of promotion than do federal appeals court judges (Baum 1997) and nonpublication of controversial decisions (Carp et al. 2020) renders such opinions “essentially invisible” (Swenson 2004, 125). Though Swenson (2004) finds no empirical support for publication as promotion behavior, she notes that even if district judges have no ambitions of promotion, they still want to have an “agreeable working environment” with other federal officials, including the “U.S. Attorney’s Offices they interact with daily” (2004, 126). This professional reputation concern is more immediate and thus might increase the likelihood a judge will choose to publish.

Based on this body of prior research, we suggest that multiple factors may play a role in the decision to publish opinions.

Hypotheses

Because the federal district courts have an enormous workload,[1] we expect that prior professional specialization may play a role in the decision to publish an opinion both as a means of decreasing workload and to further career fulfillment and enjoyment. For instance, Brenner and Spaeth (1986) find evidence of issue specialization in opinion assignment in the US Supreme Court during the Burger Court. Maltzman and Wahlbeck (1996) find issue specialization on the Rehnquist Court, as well. Similarly, Cheng (2008) finds evidence of issue specialization and opinion writing in the federal courts of appeals. Thus research suggests that judges with previous experience in specialized areas of law are more likely to publish decisions within those issue areas. Previous experience in a specialized area of law presumes that judges have a deeper level of experience and knowledge of the topic, requiring less research and time in producing a publishable opinion. Cases in areas outside the judge’s previous career experience would require greater preparation. Furthermore, judges with experience in specific areas of law likely gravitate toward those issues and may gain more personal or career fulfillment in producing opinions on those case topics.

H1: We expect that judges who specialize in certain areas of law will be more likely to publish their opinion in those cases than nonspecialists would be.

Similarly, judges with prior judicial experience at other court levels also may require less research and preparation in writing formal opinions for publication in the Federal Supplement. In our data, 21 percent of the judges who published one hundred or more opinions were former state judges. We expect that previous experience as a judge, particularly in the state courts, will positively relate to opinion publication. Only a small percentage of the judges in our sample were federal judges, such as magistrate or bankruptcy judges, who do not routinely publish opinions.

H2: We expect judges with prior judicial experience to be more likely to publish a decision than judges from nonjudicial backgrounds.

Our expectation is informed by Carp et al. (2020) who note that increasingly district court judges come from experienced backgrounds, having served as local or state judges. They note that a fairly large plurality of recent federal district court judges had previously served as judges elsewhere. Over 40 percent had served as former judges, under George H. W. Bush through Obama, an increase from earlier eras. Service as a judge previously, especially on a state court where opinions are published and released, may provide federal district court judges with confidence in publishing opinions because they have fewer start-up costs in becoming familiar with the job, especially as a new federal district court judge.

Strategic considerations by federal district court judges might also play a role in publication. Randazzo (2008) finds that US district judges condition their decisions on the expectation that the US Courts of Appeal may reverse their decision. Few decisions, roughly about 25 percent, are reversed by the circuit courts (Songer and Sheehan 1992). This suggests that when the US Courts of Appeal reverse the federal district courts, they do so because the trial court decision was an extreme divergence from the law. This principal-agent theory of judicial constraint suggests that lower courts are constrained by the American common law doctrine of stare decisis and typically fear reversal.[2] Songer and Sheehan (1990) find that true noncompliance by lower courts with precedents set by appellate courts above is unusual. While outright defiance is unusual (Carp et al. 2020), other less apparent mechanisms might be used by lower court judges as strategies to appear that they are complying with a decision even if they are not fully doing so. These techniques might include narrowing the application of the precedent or describing it as dicta.[3] A technique that has not been examined as fully is the decision to publish the opinion.

As Randazzo (2008) explains, the US Courts of Appeals exert more influence in monitoring the work of the US District Courts than the US Supreme Court because they directly oversee the work of the federal district courts. Since all decisions appealed from the federal district courts must be heard by the US Courts of Appeals, unlike the Supreme Court, which has discretionary control of its docket through certiorari,[4] the courts of appeals exert a stronger constraint on the federal district courts (Randazzo 2008). Federal district judges are also constrained by the court of appeals above them as they cannot predict which appellate panel will decide each individual case.[5] Therefore, it is possible that in certain cases where judges anticipate being reversed because the decision diverges from settled law, they may be less likely to publish their opinions in the Federal Supplement as a strategy to avoid further scrutiny of their decision. On the other hand, it is also possible that judges may anticipate reversal in a decision that falls in a gray area of the law and, therefore, those jurists may be more likely to publish the decision as a means of justifying it to the appellate court.

We expect a relationship to exist between publishing decisions and eventual reversal of the decision. However, the literature is not clear in offering a direction for the relationship between reversal and publication. On the one hand, judges may choose to publish a novel decision in order to justify their opinions because the legal issue is one that is new and needs explanation for higher courts. Alternately, judges may choose not to publish a novel decision in order to avoid notice and potential reversal. Scholarship suggests both potential relationships may exist. For instance, Randazzo (2008) finds that federal district court judges act strategically when casting votes in civil liberties cases, but that they do not do so in criminal cases where there is less policy discretion. Similarly, Boyd (2015) finds that federal district court judges are less likely to publish opinions when the circuit above is ideologically diverse, presumably because they anticipate a greater likelihood of reversal than from an ideologically congruent circuit. We test for the possibility of either relationship as an effect on publication, as it may vary given the variation in policy-making opportunities for district court judges across different types of cases.

H3: We expect judges who anticipate reversal will be less likely to publish their decision.

H4: We expect judges who anticipate reversal will be more likely to publish their decision.

Federal district judges decide important cases that matter greatly to the individual litigants appearing before them. However, though all cases are important, not all raise significant legal questions that broadly impact the rule of law. The Official Reporting Guidelines provides several criteria indicating case importance. The Federal Supplement includes a case if it is of “considerable interest to the general membership of the bar,” “advances understanding of that area of law, as opposed to a more ‘routine’ opinion dealing with well-settled or established principles of law,” and “was reached within two years of the filing date” (Platt 1996). These criteria leave quite a large area of discretion to the individual judge in determining whether a case meets them (Swenson 2004).

Given that judges desire to maintain their professional reputations in following the standards of the Official Reporting Guidelines, we expect judges will be more likely to publish an opinion in a case if its criteria meet the guidelines for publication. Swenson (2004) notes that judges will take seriously the guidelines governing publication even though they are not mandatory because they “are the primary source of law on the matter of what a judge should and should not publish” and are “the result of a respected rulemaking process” (2004, 123). The respect judges have for the rulemaking process governing their profession and the respect judges seek from their professional community (Baum 1997) may motivate judges to publish decisions that meet the official criteria despite the lack of any enforcement mechanism.

H5: We expect judges will be more likely to publish their decision if it is an important case—that is, if it satisfies the Official Publication Guidelines criteria.

Ideological agreement with the decision might also lead a judge to publish an opinion in a case. Federal district court judges decide cases alone, unlike appellate court judges, who typically sit on three-judge panels. However, it is quite plausible that a district court judge could reach a decision that she does not necessarily agree with; rather, the governing precedent and legal rules require her to reach that outcome. In these instances, judicial politics scholars would classify such judicial behavior as following a legal rather than an attitudinal model. The legal model of judicial behavior (Baum 1997) argues that judges follow the dictates of stare decisis because their training and professional socialization emphasize the importance of applying precedent. Stare decisis ensures the law maintains predictability and stability. Therefore, if judges behave as the legal model predicts, they will follow precedent regardless of their personal feelings about the outcome of the case.

On the other hand, the attitudinal model of judicial behavior (Segal and Spaeth 1993, 2002) argues that judges reach decisions consistent with their ideological views, commonly classified as either liberal or conservative. The attitudinal model presumes that judges have sincere ideological preferences in cases and that they pursue their policy preferences through the decisions they reach. We hypothesize that these models of behavior may impact the decision reached in a case, and they may also influence the decision to publish the ruling. That is, the decision to publish may be tied to or affected by an individual judge’s views on the outcome of the case. These two models’ predictions about judicial behavior lead to two competing hypotheses in the context of federal district court publication. We expect judges will publish cases regardless of whether the decision is consistent with his or her personal political views under a legal model interpretation of behavior. However, we also expect that judges will be more likely to publish rulings that are consistent with their political ideology under the attitudinal model of judicial behavior. Following Randazzo (2008) and Boyd (2015), we test both competing hypotheses to determine if ideological congruence has either a positive or negative relationship to the decision to publish and whether that relationship differs across case categories.

H6: We expect judges will publish their decision irrespective of its congruence with the judge’s political ideology.

H7: We expect judges will publish their decision if it is congruent with the judge’s political ideology.

Data and Methods

The data were derived in a two-part process from the US District Court database (Carp and Manning 2016) and from the US Courts of Appeals database (Songer 1998). The US District Court database contains coded decisions published in the Federal Supplement from 1927 to 2005. We first select judges from that database who had published at least one hundred opinions. We choose one hundred opinions as our cutoff point for several reasons. First, we reason that patterns of publication rates will be most prominent in judges whose careers span a relatively longer time. Stidham and Carp (1999) find that district court judges tend to publish most often in the middle stages of their careers. Judges serving only a few years likely encounter socialization effects that might flatten out over a longer period. Second, we reason that in order to have a sufficient sample of judges with both published and unpublished appealed opinions, the cutoff point should be rather large. Our one-hundred-case cutoff point also provides us with a sufficient number of judges from each professional experience category.

We then identify those judges’ opinions in the US Courts of Appeals database, which contains both published and unpublished opinions appealed to and decided by the nation’s appellate courts. Prior studies justify our decision to utilize appealed decisions as our primary data source. Swenson (2004) finds no substantial differences in appealed decisions versus decisions not appealed. Her data source for analyzing published versus unpublished opinions includes only appealed decisions.

We can also be reasonably certain that published and unpublished opinions are not so different that they cannot be utilized for comparison. Songer (1988) and Olson (1993) find no substantial differences of importance between published and unpublished opinions appealed to the US Courts of Appeals. Others find that many unpublished opinions still have precedential value (Reynolds and Richman 1981; Robel 1989; and Mueller 1977), which explains why the Advisory Committee on Appellate Rules of the Judicial Conference of the United States voted to allow lawyers to cite unpublished opinions in federal appeals courts beginning in 2007 (Mauro 2006). Though systematic differences between published and nonpublished decisions after 2007 are beyond the scope of this study, future research might explore whether differences exist. The vote to modify existing rules and allow unpublished opinions to be cited by lawyers, at minimum, suggests an acknowledgment that unpublished opinions are important and raise salient points of law. These unpublished opinions are not binding precedent but may be cited as persuasive authority (Magnuson and Frank 2015).

Previous findings thus suggest that appealed published and unpublished opinions are comparable for our research purposes. Given the preceding studies, we can be reasonably certain that utilizing the US Courts of Appeals database to compare unpublished and published decisions of federal district court judges is a valid and reliable data source of determinants of publication. The two-part data identification process yielded 149 federal district court judges and 3,926 total cases appealed to the US Courts of Appeals.

The dependent variable is a dichotomous variable, Published, coded as “1” if the decision was published by the federal district judge and as “0” if the decision was unpublished.

For the Specialist variable, we rely on the Federal Judicial Center’s federal judge database to obtain background information for each judge in our data. We then categorize judges as specialists for each area of law we model separately, coded dichotomously with “0” indicating nonspecialist and “1” indicating the judge has prior career specialization in each specific area of law. Many of the judges are specialists in more than one area. The career specialist variables we include are for criminal law, civil liberties, and economic case specialties. Using the same data source, we also separately code background career information for each judge indicating whether they previously worked as a Politician, State Judge, US Magistrate, Law Professor, or Private Practice attorney. Each of these variables is coded dichotomously with “1” indicating the judge previously served in the role, “0” indicating they did not.

The second category of independent variables includes specific case characteristics. The first case variable we characterize as case importance.[6] This variable is coded “1” if the decision was Important, “0” if not. The case importance variable indicates whether the decision by the federal district court meets the criteria of the Official Publication Guidelines. We rely on data from the US Courts of Appeals database to determine if the case raised an important issue of constitutional law or federal law. These we deem as important issues.

The second case-specific variable is Reversal. We code this variable as “1” if the appeals court reversed the district court’s decision and “0” if it affirmed it.

The final case-specific variable is Ideological Congruence with the decision. If the federal district judge’s ideology is congruent with the decision they made, we coded it as “1”; otherwise it was coded as “0.” Cases are classified as liberal or conservative in their outcomes and judge ideology is classified as Democrat or Republican-appointed.[7] In our models, this variable is coded dichotomously with Democrats coded as “1,” Republicans coded as “0.”

Besides political party affiliation, our models also control for personal attributes, including sex and race of the judge, to determine whether differences in publication within various case categories exist between judges from various backgrounds. In the federal district courts, some research shows that women and minorities may behave differently from their colleagues when managing their caseloads or communicating with litigants (Boyd 2013). Other research shows freshmen effects and self-silencing behavior may occur more frequently among women and minorities (Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker 2012; Childs and Krook 2006; Allen and Wall 1993). We include these controls to examine whether opinion-writing patterns also reveal self-silencing or freshmen effects behavior.

Females are coded as 1, and males are coded as 0. Minority judges are coded as 1, and Caucasians are coded as 0.

The cases are divided into three general case categories, relying on the coding of the US Courts of Appeals database: criminal, civil liberties, and economic cases. Since our dependent variable—publication—is dichotomous, we use logistic regression to estimate each model.[8]

Results

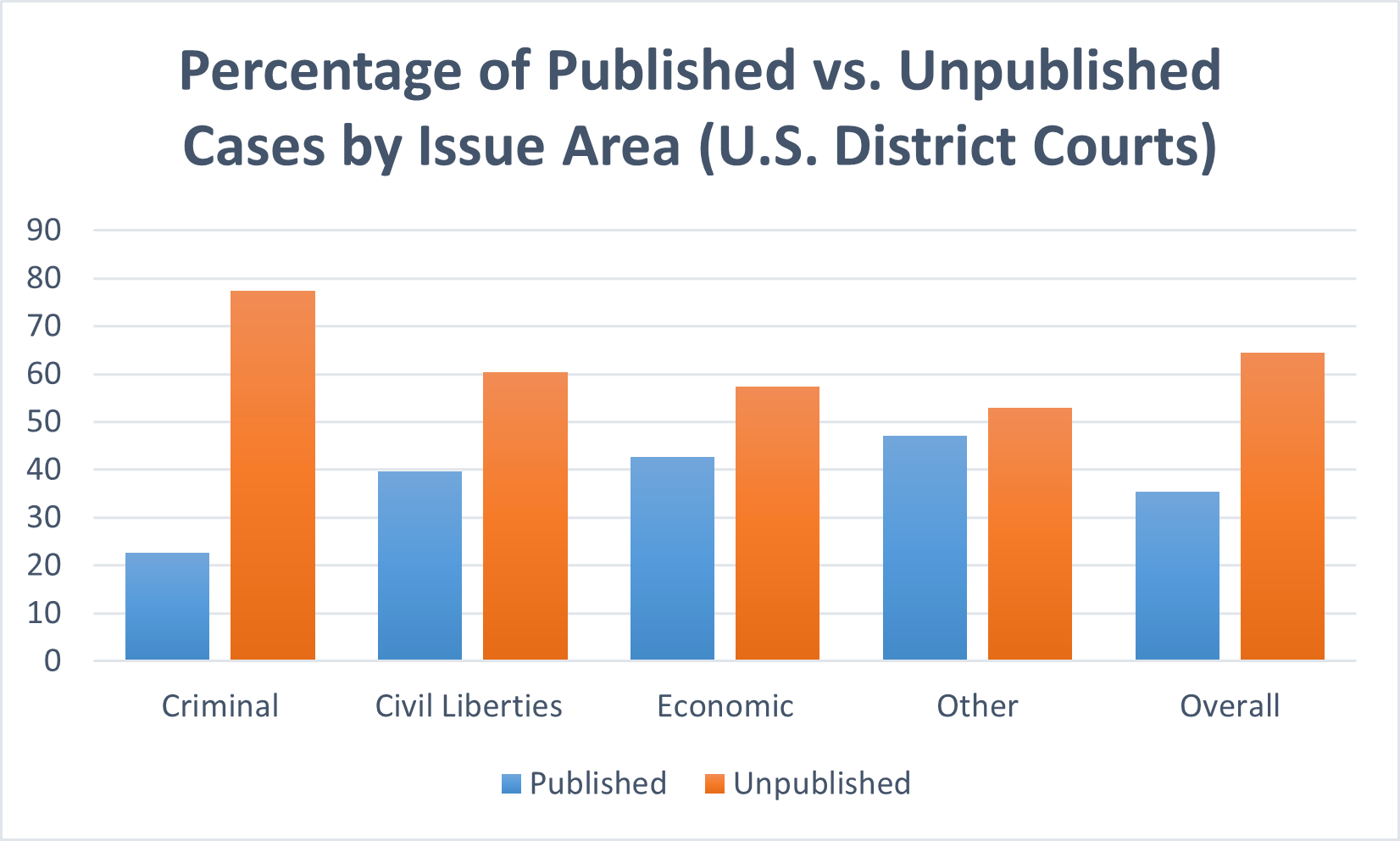

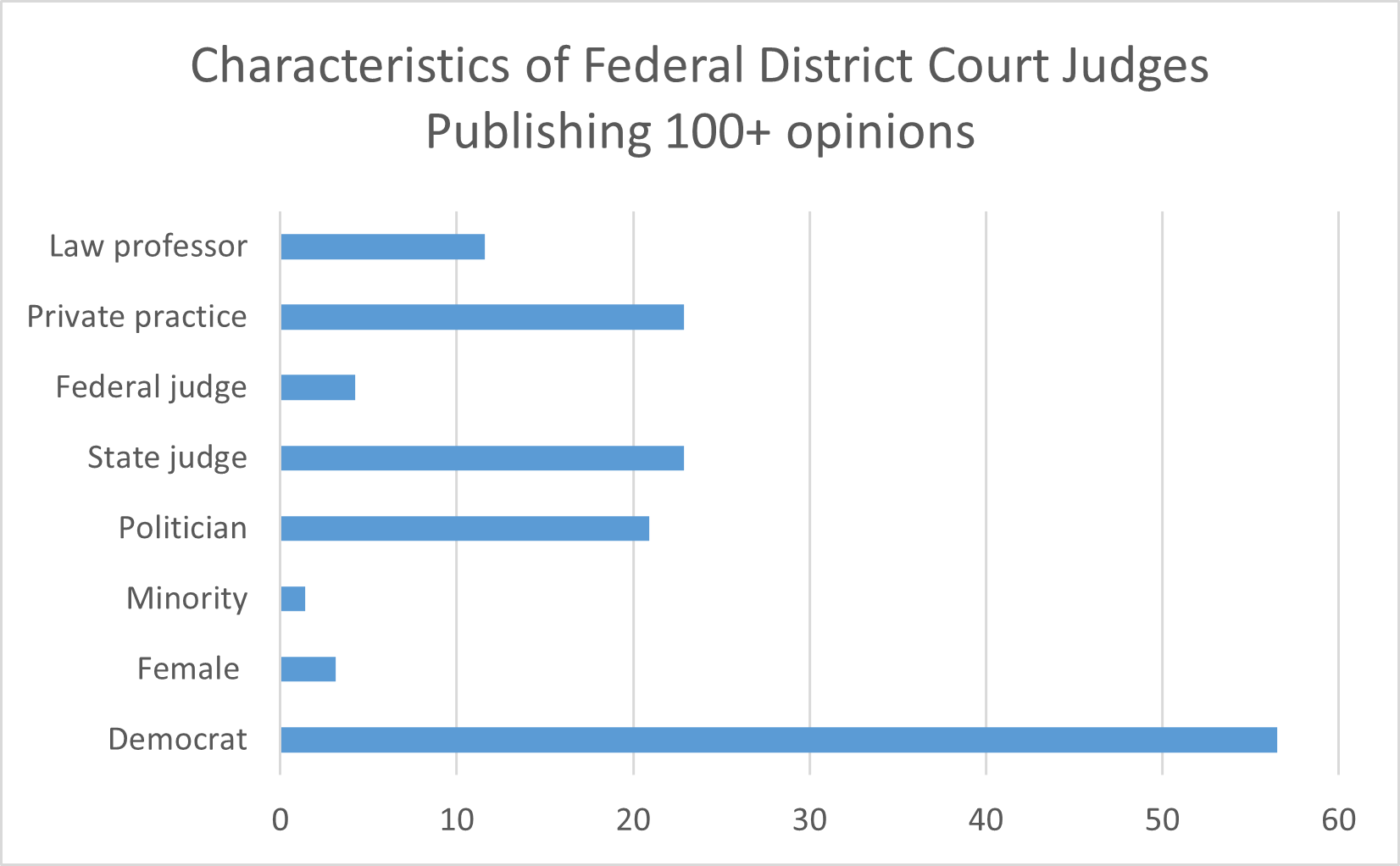

First, we present summary charts of the distribution of published and unpublished decisions in our data by issue area. Figure 1 shows only 23 percent of criminal cases in our data are published, compared with roughly 40 percent of civil liberties and economic cases. Overall, about 35 percent of cases in our data are published opinions. Figure 2 shows the background characteristics of the judges in our data. Over half were appointed by Democrats and only a small percentage, less than 5 percent, are women or minorities. The career backgrounds are about evenly distributed between private practice attorneys, former state judges, and politicians, with just over 20 percent for each. Fewer former law professors and US magistrates appear in our data. Our data do not, unfortunately, subcategorize former state judges by the level of court they served on previously.

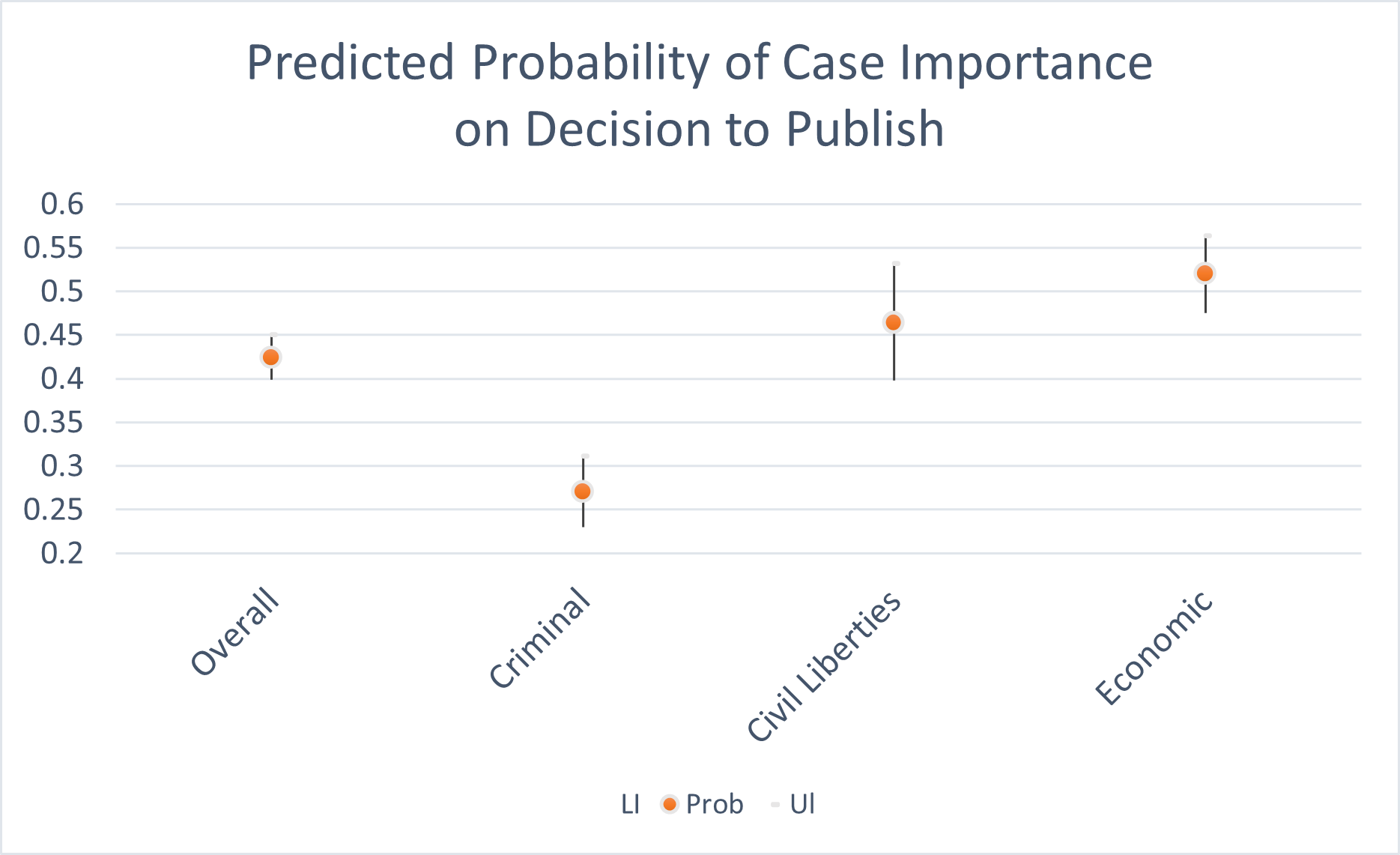

The results of the logistic regression analyses are shown in Appendix A. The overall model and all three case-category models are statistically significant at the 0.000 level. Across all four models the variable, Important, is positively signed and statistically significant, providing support for H5. We are thus confident that case importance increases the likelihood a decision will be published, irrespective of the legal issue raised. Figure 3 shows the predicted probability of case importance on the likelihood of publication. For cases overall, the predicted probability of a published decision when a case is deemed “important” is 0.42. In comparison, cases not classified as important have a 0.32 predicted probability of publication. The predicted probability of case importance increases to 0.46 when it presents a civil liberties issue and 0.52 when the case involves an economic issue.

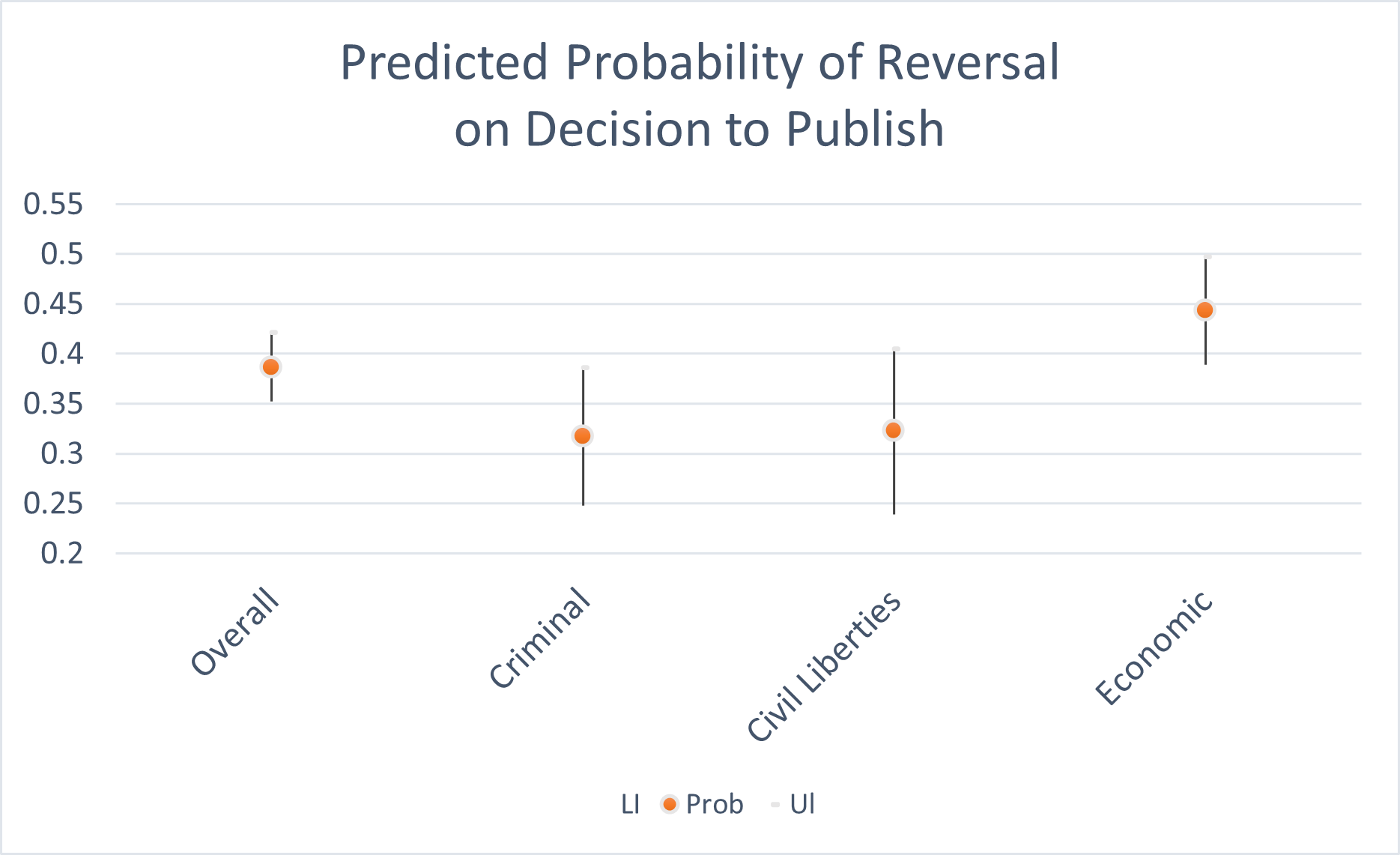

Anticipation of eventual reversal by the US Courts of Appeals also appears to impact publication.[9] Overall and in criminal cases, eventual reversal predicts publication, providing support for H4. However, in civil liberties cases, eventual reversal has a negative impact on publication, consistent with H3. That is, civil liberties cases that are eventually reversed are less likely to be published. The predicted probabilities for reversal are shown in figure 4. Overall, the predicted probability of publication in cases that are eventually reversed is 0.39. In criminal cases, district court judges have less policy discretion because cases often turn on factual evidence in a criminal trial (Randazzo 2008). However, in civil liberties cases, Randazzo (2008) finds district court judges have greater levels of policy discretion. In areas with greater policy discretion, it appears district court judges may anticipate reversal and thus suppress their decisions via nonpublication. However, in criminal cases where there is less policy discretion for district court judges, they do not anticipate reversal, and in fact, it appears they may seek appellate court input in applying legal standards to factual evidence.

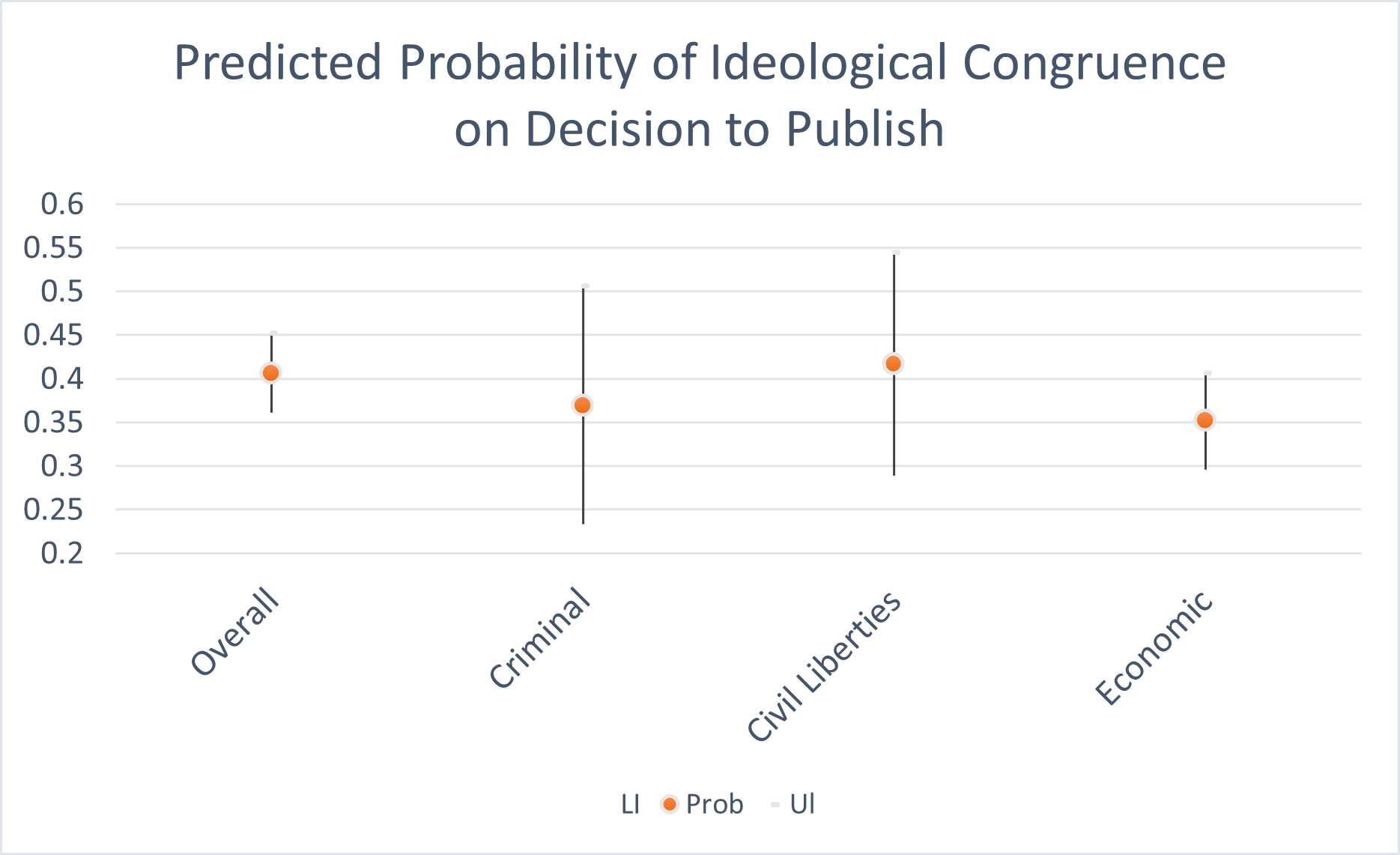

Finally, of the case-specific factors, ideological congruence has a statistically significant impact on publication overall and in criminal and economic cases. Appendix A shows a positive relationship between publication and the ideological disposition of the judge in criminal cases, consistent with an attitudinal model of behavior and H7. However, in economic cases, ideological congruence decreases the likelihood of publication, consistent with a legal model of judicial behavior and H6. These results are illustrated as predicted probabilities in figure 5. The predicted probability of a judge publishing a decision that corresponds to his or her political ideology is 0.41. That is, the data indicate that in economic cases jurists are more likely to publish their decision if it is consistent with their own ideological viewpoint. Again, these differences are likely due to differences in the amount of policy-making discretion district court judges have in different areas of law (Randazzo 2008).

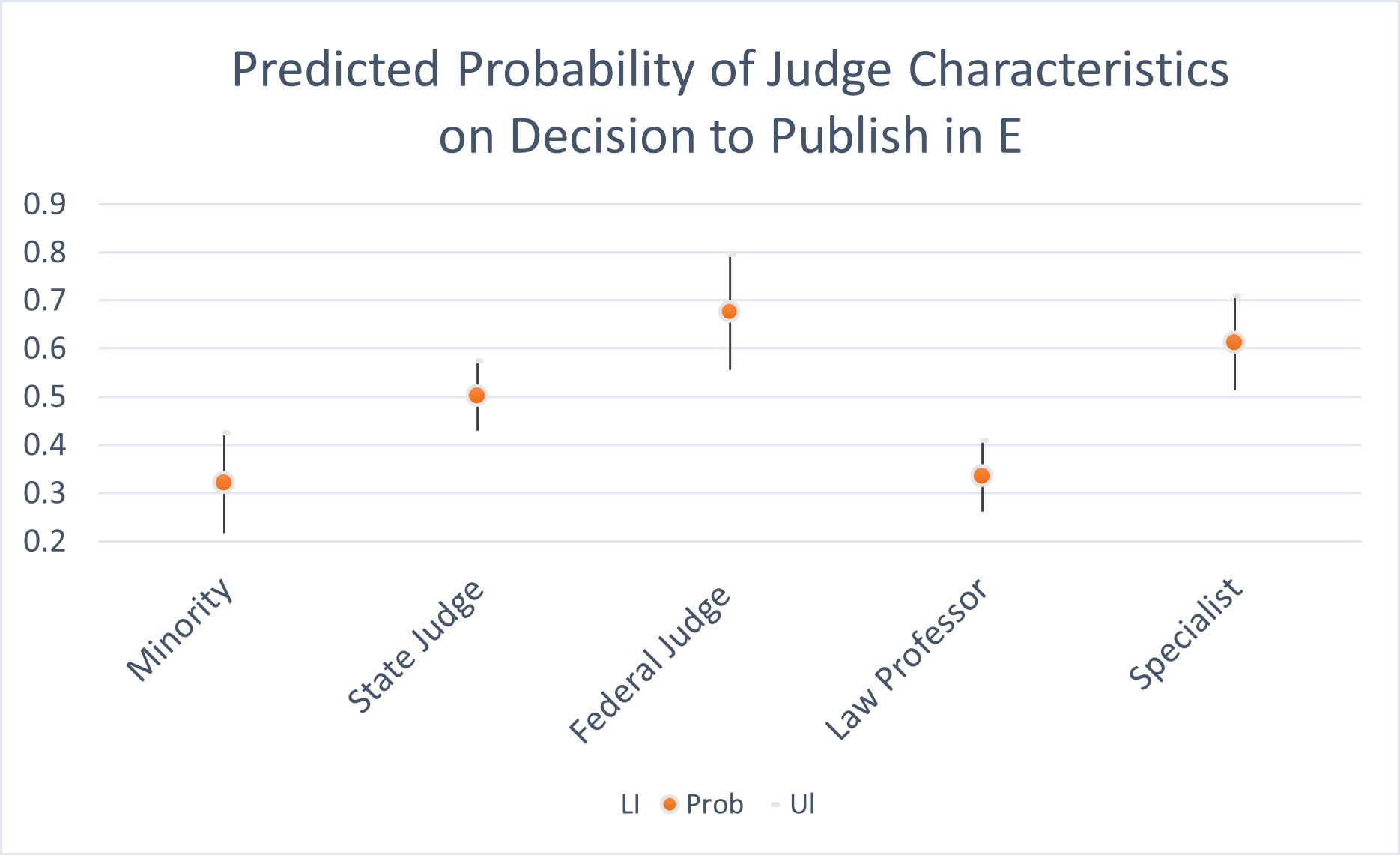

The judicial background variables reach statistical significance in some of the models but are not consistently impactful across various case categories, suggesting partial support for H2. For instance, Appendix A shows that the minority judges in our data are less likely to publish overall, and particularly in economic cases that could be due to a possible self-silencing effect. Former state judges are less likely to publish their rulings in criminal cases but are more likely to publish if the case raises an economic issue. In fact, in economic cases, judicial backgrounds have the largest impact on the likelihood of publication. The predicted probabilities for publication in economic cases are shown in figure 6. In economic cases, former federal magistrates publish more often than others, while former law professors publish less often. Also, only in economic cases does the Specialist variable reach statistical significance. If a judge formerly worked in the area of economic law, he or she is more likely to publish decisions that are economic in nature, providing partial support for H1.

Discussion and Conclusion

We can surmise several important findings from the analyses. First, case importance consistently affects whether a case is published. The consistency of case importance in the decision to publish suggests that federal district judges act as professionals in their compliance with the Official Publication Guidelines. This indicates that the professional standards of publication are generally adhered to by federal district court judges, even though the language of the guidelines could be interpreted broadly and with a great deal of discretion.

Second, the findings suggest federal district judges only in certain circumstances act strategically to avoid reversal. They are more likely to publish decisions that eventually are reversed by the US Courts of Appeals overall and in criminal cases, suggesting lack of strategic action. It may be that judges publish opinions that are eventually reversed because the case raises a legal issue that requires resolution by an appellate court, or the case introduces a new issue in a newly developed area of law. Judges might also be motivated to publish opinions, even if they are eventually reversed, because they desire to provide more support and justification for their ruling to the appellate court or because the case turns on a factual determination where reversal cannot be anticipated.

However, in civil liberties cases, judges were actually less likely to publish if the decision was eventually reversed. Civil liberties cases—which include matters like freedom of speech, reproductive rights, and religious liberty—raise issues that in some respects are more salient to the public and potentially controversial. Thus it is possible that federal district judges act strategically in civil liberties cases by failing to publish opinions where they anticipate reversal. Randazzo (2008) argues that if the “federal trial judges anticipate a negative response on appeal, then they curtail their ideological influences,” and he finds that “this pattern remains consistent when one examines civil liberties and economic cases, but not for criminal cases…where judges do not possess the discretion to act according to their ideological preferences, and consequently, do not anticipate how their decisions will be treated by the appeals courts” (686).

Consistent with previous research, we find that federal district court judges largely follow the Official Publication Guidelines when deciding which cases to publish. However, we also find some key distinctions across different case types, with strategic anticipation of reversal playing a role in publication along with policy-making discretion. Where federal district judges are less constrained—that is, in civil liberties cases—they publish less when anticipating reversal. However, in criminal cases where there is less policy discretion, judges cannot as easily anticipate eventual reversal. This finding on reversal and publication is largely consistent with Bowie, Songer, and Szmer (2014) who find that judges on the US Courts of Appeals do not worry too much about reversal because they do not have a good sense of which decisions will be granted cert by the US Supreme Court. However, a much higher likelihood of review and probability of reversal exists for district court judges. Thus as Randazzo (2008) finds, they do act strategically to an extent. Further, Bowie, Songer, and Szmer (2014) in interviews with federal appeals court judges find that they behave in ways to maintain their professional reputations. Our findings suggest these same concerns exist for federal district court judges, as well.

Judges appear to publish decisions that correspond to their ideological views overall and in criminal cases. However, in economic cases, ideological congruence is less likely to lead to publication. This might suggest that some areas of law raise issues that are more significant to a judge’s personal view, while these same judges are perhaps less passionate about cases that touch upon economic matters. In fact, the results show that economic cases’ publication is impacted differently than criminal and civil liberties cases. Judges’ backgrounds and expertise explain more frequent publication in economic cases. This is not surprising given the technical nature and expertise required in many complicated economic cases. However, while career background and expertise matter more in economic cases, these factors largely do not explain publication decisions in other areas of law. Consistent with Boyd (2015), personal characteristics have less impact on publication overall than do case-specific factors such as case importance, anticipation of reversal, and ideological congruence.

It is worth noting that there are a few caveats to keep in mind in the interpretation of the results. We limit our analysis to include only judges who serve long enough to have decided 100 cases or more, which reduces the number of women and minorities in our data. We also include only cases that had been appealed to the US Courts of Appeals. And because of the nature of our models, we were unable to control for circuit effects because of lack of variation in judge characteristics across each circuit. Other research on publication in the federal district courts (Boyd 2015; Swenson 2004) examine circuit effects and do not limit the analysis to judges deciding at least one hundred cases. However, these studies are limited by examining only a few circuits (Swenson 2004) or select case categories (Boyd 2015), while our study focuses on a longer period and across all circuits and case categories.

These limitations aside, one interesting indication of this line of research is that case importance, where analyzed, positively affects publication. Together, the body of research suggests that federal district court judges generally adhere to the Official Publication Guidelines when publishing cases and they do so consistently. In this aspect of the decision-making process, federal district court judges can be viewed as unbiased professionals who largely follow the norms and expectations of the legal community even when they seemingly have a large amount of discretion. Our findings also suggest that judges tend to publish decisions that correspond to their own ideological views. In this way, our research indicates that judicial ideology is an important factor influencing judges’ decisions to publish their rulings.

Learning Activity

Survey the Data

First, navigate to https://www.umassd.edu/cas/polisci/resources/us-district-court-database/ to download the US District Court database by Carp & Manning (2016). After downloading the data, tabulate the frequencies of judges contained in the database. Each observation represents a single, published case. For Stata users, the command to tabulate frequencies is “tabulate judge, sort.” This command will provide a list of judges sorted by frequencies of their published opinions.

Second, navigate to: https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges. Explore the biographical information for a selection of the judges who published one hundred or more opinions from the frequencies list above. Create background profiles for a few of these judges. What background characteristics do they have in common? Based on your preliminary survey of the judges, what additional variables would you include to predict publication in certain types of cases? Are there variables you would include that are not included in the authors’ model presented in the study?

References

Allen, David W., and Diane E. Wall. 1993. “Role Orientations and Women State Supreme Court Justices.” Judicature 77:156–65.

Baum, Lawrence. 1997. The Puzzle of Judicial Behavior. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bowie, Jennifer Barnes, Donald R. Songer, and John Szmer. 2014. The View from the Bench and Chambers: Examining Judicial Process and Decision Making on the U.S. Courts of Appeals. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Boyd, Christina L. 2013. “She’ll Settle It?” Journal of Law and Courts 1 (2): 193–219.

———. 2015. “Opinion Writing in the Federal District Courts,” Justice System Journal 36 (3): 254–73.

Brenner, Saul, and Harold J. Spaeth. 1986. “Issue Specialization in Majority Opinion Assignment on the Burger Court.” Western Political Quarterly 39 (3): 520–25.

Carp, Robert A., and Kenneth L. Manning. 2016. “U.S. District Court Database.” 2016 version n=110977. http://districtcourtdatabase.org.

Carp, Robert A., Kenneth L. Manning, Lisa M. Holmes, and Ronald Stidham. 2020. Judicial Process in America. Washington, DC: Sage/CQ Press.

Carp, Robert A., Ronald Stidham, and Kenneth L. Manning. 2010. The Federal Courts. 5th ed. Washington DC: Sage/CQ Press.

Cheng, Edward K. 2008. “The Myth of the Generalist Judge.” Stanford Law Review 61 (3): 519–72.

Childs, Sarah, and Mona Lena Krook. 2006. “Should Feminists Give Up on Critical Mass? A Contingent Yes.” Politics & Gender 2 (4): 522–30.

Dolbeare, Kenneth M. 1969. “The Federal District Courts and Urban Public Policy: An Exploratory Study (1960–1967).” In Frontiers of Judicial Research, edited by Joel Grossman and Joseph Tanenhaus. New York: Wiley.

Karpowitz, C., T. Mendelberg, and L. Shaker. 2012. “Gender Inequality in Deliberative Participation.” American Political Science Review 106 (3): 533–47.

Law, David S. 2006. “Voting and Publication Patterns in Ninth Circuit Asylum Cases.” Judicature 89:212–19.

Maltzman, Forrest, and Paul J. Wahlbeck. 1996. “May It Please the Chief? Opinion Assignments in the Rehnquist Court.” American Journal of Political Science 40 (2): 421–43.

Magnuson, Eric J., and Nicole S. Frank. 2015. “Briefly: Because Someone Said So, That’s Why.” Minnesota Lawyer, July 16, 2015. https://minnlawyer.com/2015/07/16/briefly-because-someone-said-so-thats-why/.

Mauro, Tony. 2006. “Court Endorses Use of Unpublished Opinions.” Legal Times. http://www.nonpublication.com/mauro4.12.htm.

Mckenna, J. A., L. L. Hooper, and M. Clarke. 2000. Case Management Procedures in the Federal Courts of Appeals. Washington, DC: Federal Judicial Center.

Mueller, J. E. 1977. “Unpublished Opinion Study.” State Court Journal 1:23.

Olson, S. M. 1993. “Studying Federal District Courts through Published Cases: A Research Note.” Justice System Journal 15:782–800.

Platt, Ellen. 1996. “Unpublished vs. Unreported: What’s the Difference?” In Perspectives: Teaching Legal Research and Writing, 26–27. St. Paul, MN: West.

Randazzo, Kirk. 2008. “Strategic Anticipation and the Hierarchy of Justice in the U.S. District Courts.” American Politics Research 36 (5): 669–93.

Reynolds, W., and W. Richman. 1981. “An Evaluation of Limited Publication in the U.S. Courts of Appeals: The Price of Reform.” University of Chicago Law Review 48:573.

Robel, L. K. 1989. “The Myth of the Disposable Opinion: Unpublished Opinions and Government Litigants in the U.S. Courts of Appeals.” Michigan Law Review 87:940.

Rowland, C. K., and Robert A. Carp. 1996. Politics and Judgment in the Federal District Courts. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Segal, Jeffrey, and Harold Spaeth. 1993. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2002. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Songer, Donald R. 1988. “Nonpublication in the United States District Courts: Official Criteria versus Inferences from Appellate Review.” Journal of Politics 50:206–19.

———. 1998. “The Multi-user Database on the United States Courts of Appeals, 1925–1996.” http://www.songerproject.org/data.html.

Songer, Donald R., and Reginald S. Sheehan. 1990. “Supreme Court Impact on Compliance and Outcomes: Miranda and New York Times in the United States Courts of Appeals.” Western Political Quarterly 43:297–316.

———. 1992. “Who Wins on Appeal? Upperdogs and Underdogs in the United States Courts of Appeals.” American Journal of Political Science 36:235–58.

Stidham, Ronald, and Robert A. Carp. 1999. “Exploring Opinion Writing Practices of Federal District Judges.” Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southwestern Political Science Association, San Antonio, TX, April 1, 1999.

Swenson, Karen. 2004. “Federal District Court Judges and the Decision to Publish.” Justice System Journal 25:121–42.

Taha, Ahmed E. 2001. “Publish or Paris? Evidence of How Judges Allocate Their Time.” Unpublished paper.

Vestal, Allan D. 1966. “A Survey of Federal District Court Opinions: West Publishing Company Reports.” Southwestern Law Journal 20:63–96.

———. 1970. “Publishing District Court Opinions in the 1970’s.” Loyola Law Review 17:673–91.

Appendix: Logistic Regression Model, Likelihood of Publication in the Federal Supplement

| Overall model MLE (SE) |

Criminal MLE (SE) |

Civil liberties MLE (SE) |

Economic MLE (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democrat | 0.038

(0.081) |

0.159

(0.149) |

0.228

(0.218) |

0.038

(0.131) |

| Female | -0.050

(0.246) |

-0.240

(0.465) |

0.354

(0.725) |

-0.238

(0.381) |

| Minority | -0.325*

(0.162) |

-0.320

(0.345) |

-0.343

(0.394) |

-0.533*

(0.259) |

| Politician | -0.012

(0.098) |

-0.332

(0.222) |

0.310

(0.248) |

-0.191

(0.174) |

| State judge | -0.140

(0.111) |

-0.454*

(0.229) |

-0.206

(0.246) |

0.336*

(0.177) |

| Federal judge | 0.091

(0.141) |

-0.177

(0.350) |

-0.475

(0.497) |

1.078**

(0.302) |

| Private practice | 0.023

(0.093) |

0.004

(0.208) |

0.205

(0.261) |

0.206

(0.161) |

| Law professor | 0.005

(0.115) |

0.228

(0.234) |

0.232

(0.273) |

-0.501**

(0.195) |

| Specialized in issue area | – | -0.229

(0.194) |

0.340

(0.708) |

0.800**

(0.229) |

| Important issue | 0.470**

(0.628) |

0.369**

(0.129) |

0.505**

(0.196) |

0.524**

(0.116) |

| Reversed by appeals court | 0.180*

(0.089) |

0.571**

(0.191) |

-0.439*

(0.229) |

0.051

(0.143) |

| Ideological congruence with decision | 0.272**

(0.105) |

0.767*

(0.313) |

0.124

(0.308) |

-0.466**

0.145 |

| Constant | -0.845**

(0.086) |

-0.229

(0.194) |

-0.732**

(0.211) |

-0.386**

(0.139) |

| – | N=3720 Chi2 = 68.48*** Count R2 = 64.9 |

N=1398 Chi2 = 45.69*** Count R2 = 77.4 |

N=526 Chi2 = 22.32** Count R2 = 62.7 |

N=1322 Chi2 = 89.82** Count R2 = 60.7 |

*Significant at .05 level, **significant at .01 level, two-tailed tests.

- Recent data indicates the workload of the federal district courts well exceeds three hundred thousand cases filed annually (Carp et al. 2020). ↵

- Stare decisis is the doctrine of following precedent. Judges are bound to follow prior precedents set by their own courts’ previous decisions (horizontal stare decisis) and by precedents set by appellate courts above them in the judicial hierarchy (vertical stare decisis). Principal agent theory suggests lower courts are the agents of higher courts in the judicial hierarchy and that their primary role is norm enforcement by applying legal precedents to cases before them as handed down by the appellate courts above. Principal agent theory as applied to judicial behavior examines the extent to which lower courts comply with appellate courts above them, especially when their policy preferences differ from the decision handed down from the appellate court (Baum 1997). ↵

- Dicta refers to language in a case that is not central to its holding. ↵

- The US Supreme Court decides less than one percent of all cases appealed to them from state supreme courts and the US Courts of Appeals by selectively granting certiorari to the few cases they deem to be cert-worthy (Carp et al. 2020). Cases are typically granted certiorari when they raise significant national issues and when conflict in the rule of law exists between the various circuits. ↵

- The US Courts of Appeal operate using rotating panels of three judges randomly assigned. ↵

- For our purposes, we rely on the US Courts of Appeals database classification of case importance (Swenson 2004) since the federal district court database includes only published opinions and the appeals court database includes both published and unpublished. While relying solely on the appellate court’s determination of case importance could potentially exclude some cases deemed “important” by the federal trial court, it is the only consistent measure of case importance available across both published and unpublished decisions (Swenson 2004). ↵

- We utilize political party of the appointing president as our measure of judge ideology because it is a consistent measure across our time period, unlike other measures of judge ideology for federal judges. ↵

- Initially, we specified models with narrower case categories to correspond with the judge’s specific career specialization, but these did not yield sufficient observations suitable for analysis. We also specified models that controlled for the federal circuit where the federal district court resides. In all alternate models tested, the general trend was that judge attributes varied in their significance levels and were not consistent across models. However, consistently across various model specifications, the importance variable remained statistically significant and positive. Unfortunately, alternate specifications with circuit controls could not be successfully estimated across all case categories due to insufficient variation in judge characteristics across the various circuits. ↵

- While reversal is not a perfect measure of anticipated reversal, it is the most consistent across our data for both published and unpublished decisions and is most often used by previous research to measure anticipated reversal (Bowie, Songer, and Szmer 2014; Randazzo 2008). ↵