Chapters

Chapter 9: State and Local Bureaucracy and Administration

9.A – Introduction

When many Americans think about government bureaucracies, negative stereotypes immediately come to mind – adjectives such as “red tape-bound,” “impersonal,” “unresponsive,” “lethargic,” and “undemocratic” are associated with those stereotypes. Similarly, bureaucrats themselves are often labeled as “lazy,” “incompetent,” “insensitive,” and “power hungry.” However, even though many Americans carry these negative stereotypes around in their reservoir of thinking, most adults in the workforce are employed by some type of private, public or nonprofit bureaucracy and depend on government bureaucracies for a wide range of services provided by such bureaucracies as schools, hospitals, fire and police agencies, the U.S. Postal Service, the Social Security Administration, etc. Without bureaucracy, very little in the way of public services would be provided in modern society. In addition, the social, economic and ecological sustainability we need to promote all depend on the institutional sustainability of those entities of state and local government, which endeavor to organize and implement government policies and programs.

Despite the broadcast media’s inordinate focus on the national government, state and local governments actually create and implement the vast majority of public policy, often serving as critical linkages between elected and administrative personnel working at all levels of U.S. government. The number of sub-national governmental units, particularly special districts, continues to grow vigorously in the United States. New units of government reflect growing and changing demands on the part of local communities. More extensive government often means a greater number of elected officials and public administrators (or bureaucrats). For the reader interested in careers in state and local government, employment opportunities in public administration experienced tremendous growth over the past decade and this workforce expansion involved the creation of opportunities for persons possessing a wide variety of skill sets and abilities.

Learning Objectives

With this setting as a backdrop, this chapter will discuss:

- the basic tenets of bureaucracy,

- administration conceptualized as a system,

- networking,

- knowledge, skills and abilities of the 21st century administrator,

- women and minorities in public administration,

- e-government,

- volunteers and public and non-profit administration in local communities,

- historic trends in state and local of government employment,

- salary trends in state and local government,

- and state and local agencies’ initiatives in place for working towards sustainability and adaptive innovation in the promotion of resilient communities.

9.B – What is Bureaucracy?

Bureaucracy is nearly as old as civilization itself. Any reader who has had an interest in archaeology, for instance, knows that some of the earliest examples of human writing are the official documents of bureaucrats or public administrators. The Sumerian clay-tablets, found in present day Iraq, were written by official government scribes — the bureaucrats of that long-lost society! Bureaucrats are the most visible aspect of government in daily life; consumers of government goods and services have regular contact with postal workers, law enforcement personnel, road repair or sewage engineers, the water department, traffic engineers, city planners, and many other administrators and representing local, state, and national administrative agencies.

Formally stated, the term bureaucracy reflects a rationally organized hierarchical structure and administrative process composed of professional individuals working in and communicating from well-defined positions placed within a coordinated formal structure intentionally designed to achieve complex goals with maximum effectiveness and efficiency. Bureaucracy is, therefore, a specific type of formal organization. In the late-19th century, a highly regarded sociologist by the name of Max Weber (pronounced “Vey-bur”) wrote a now-famous treatise on the “ideal” bureaucracy, and this treatise is considered to this day the definitive definition of the term bureaucracy for scholars and researchers worldwide.1

Weber developed his thinking on bureaucracy on the basis of a close study of many large formal organizations widely regarded as successful in his day, and he identified what he took to be the principal characteristics of a perfect or “ideal type” bureaucracy – that is, an organization of large scale that could accomplish very difficult tasks such as the mass production of complex durable goods, the harnessing of the energy of a mighty river, or the gaining of victory in armed combat with a worthy adversary. Not only was it possible to accomplish these grand tasks, but also the goals could be attained with maximum effectiveness and efficiency. One of the basic assumptions of Weber’s model was that the ideal bureaucracy could accomplish any goal in any nation, be it the production of goods or services for the private market or the provision of goods and services for a town, city, state or nation. Weber thought of bureaucracy as reflecting the application of science to the task of building organizations, with science taking the form rationality (as opposed to tradition, family ties, religious preference, myth, sentiment, etc.) in the design and management of a formal organization. The design of the organization reflects a scientific division of labor and a type of management characterized by the pursuit of effectiveness and efficiency without regard to personal favor or sympathy.

Bureaucracies in this Weberian ideal type sense are composed of professional individuals who are carrying out specialized tasks requiring specialized training and/or targeted experience. Professionalism is a very important concept in bureaucracy, and the idea is closely tied to the subject of this book — namely, the capacity to build innovative, adaptive and sustainable communities, and to promote the ability among state and local government public administrators to develop the plans, policies and programs in their respective governments and agencies that facilitate the maintenance of sustainable communities. Professionalism first entails the idea that an individual who occupies an important position in a bureaucracy has gone through appropriate formal education and/or training that prepares him or her to carry out the duties of their position. Professionals require both appropriate prior education/training and a commitment to lifelong learning related to their chosen profession. With respect to sustainability, such learning is an absolute necessity as our knowledge expands regarding global climate change and what types of state and local government problem solving challenged will have to be taken on in the coming decade, and beyond.

Along with professionalism, communication is another very important component in the operation of an ideal type bureaucracy. In Weber’s bureaucratic model, communication was a direct function of an individual’s position within the hierarchy of a bureaucratic system. Accordingly, the boss communicates “down” to the worker in a manner that is unique to being a boss; workers may communicate to each other, but they take orders from their boss and do not communicate back to him or her unless asked to do so. Formal communication, both written and oral and which concerns decision-making, is documented so that there is strict accountability for all outcomes (successes and failures alike) and a record of activities can be carefully studied to improve effectiveness and efficiency.

Finally, bureaucracy in the Weberian sense was developed to accomplish complex goals — such as the mass production of consumer goods like automobiles or the establishment of rural electrification in a nation — through the scientific division of labor. This specially created structure called bureaucracy designates the specialization of tasks and the careful coordination of activities, using a hierarchy of official positions. The bureaucratic system uses official channels of communication where activities are documented as to who decided what, to what effect, and at what cost to the organization. Complex goals virtually always entail long-term objectives, involving problems that cannot be solved easily or quickly. From your reading of earlier chapters, you realize that good governance in state and local government entails a strong dose of bureaucracy viewed in this Weberian framework.

Weber’s ideal type model is an important place to start in our discussion of organizational forms present in state and local government, but it is fair to ask the question: Do things really work this way in practice? The simple answer is “no.” While bureaucratic structure is easily discernible in state and local government, everyday work activities are a great deal more varied and complex than the ideal type model would lead one to believe. It can be said that, for the most part, formal structure does not accurately describe the nature of work carried out in state and local government. This being the case, it is fair to pose another leading question: Is there a better way to inform ourselves regarding the actual role of public administration and public administrators in the governance process? Fortunately, the answer to that question is “yes!”

9.C – Moving from Bureaucracy to Administration as a System

If an individual were to visualize bureaucracy as an object, how would it be represented? While some would say a python with all the negative connotations, a more common and realistic perspective would be that of a pyramid. Just as the pyramids have a single tip at the top, so too do bureaucracies — they have one official leader. The base of a pyramid is wide, which could be symbolic of a large number of offices or positions all reporting to the top of the bureaucracy. Similar to a pyramid, bureaucracy is viewed as largely immutable and enduring. Bureaucracy is seen as an inelastic and highly structured process — something that endures despite changes in the world around it. Viewing state and local government bureaucracy and bureaucrats in this Weberian light would convey the impression that they are not active participants in governance; bureaucrats would simply do the bidding of elected officials. With all of the training and professionalism required of bureaucrats, however, would it not be wasteful to leave such a large group of well-trained, well-informed and experienced persons out of the state and local government governing process? It turns out that while the Weberian ideal type model of bureaucracy would have us believe that bureaucrats in state and local government are simply passively carrying out the directives of their politically elected “bosses” in the legislative and executive offices of government, the truth is that there is a far more active role for state and local government bureaucrats in American government.

The recognition of a legitimate active engagement role for bureaucracy in governance began when Public Administration and Political Science scholars and reflective practitioners in government service began to conceptualize public administration as an organic process. What would organic administration look like? Unlike bureaucracy, an organic process would view public administration in the United States as a highly collaborative enterprise involving people (animate administrative professionals) rather than offices and official positions.2 In an organic process, individuals within an organization are seen as possessing unique conditions and values, characteristics that causes them to shape the organizational mission and accomplishment as well as strategic planning for the future.3

Additionally, within the paradigm of active engagement the act of administration includes an interactive process occurring between professionals and citizens rather than involving simply a one-way bureaucratic enterprise of policy implementation strictly following the dictates of elected officials.4 The socio-political environment is affected by what administrators will do and how they will accomplish their goals; responsiveness to changing conditions is critical for state and local government agencies.5 In the area of parks and recreation, for instance, the changing demographics of our population and changing tastes and preferences of succeeding generations require that the locations and programming available reflect changing patterns of use and demand. Organic administration entails the active interaction between legislative and executive officials and bureaucrats occurring within a network that is adaptive, one that is capable of responding to the ever changing needs of agency clientele and balancing these adaptive adjustment concerns with the need for the efficient use of public funds. Public administrators are expected to take part in this interaction as able and confident collaborators.

In the 21st century, governance at the state and local level clearly entails building and supporting sustainable communities.6 Sustainability necessarily implies the core traits of adaptability and innovation. While these traits may create desired outcomes in the statutes and ordinances placed into law by elected officials, the accomplishment of these outcomes requires the active involvement of public administrators responding to changing local, state, national, and even international conditions.7

Around the country – in urban, suburban and rural areas alike – public administrators, non-profit agency managers, and private organizations are increasingly working in an environment in which they attempt to learn from each other and communicate, coordinate and collaborate to bring solutions to the attention of elected officials to whom they report.8 Administrative capacity for such adaptation and innovation borne of a collaborative learning process is a critical element in the promotion of sustainability in American state and local government. It is very important that U.S. state and local government not become so much the victim of the “hollow state” phenomenon — a concept of minimalist government entities and maximum use of contracted services9 — that collaborative learning in service of sustainability does not take place.10

9.D – Networks to Somewhere: The Intertwined Process of Administrative Governance

Network organizations are a type of formal organization that is substantially different from the Weberian ideal type bureaucratic model. The network organization is touted as a genuinely modern arrangement facilitated by the revolution in intra- and inter-organizational communication permitted by computers and the Internet, but the concept itself is quite long- established. A reading of the history of organizations that successfully adapt to change in their environments suggests that those organizations which maintain extensive “boundary spanning” activities do tend to make adaptations that make them resilient to changes in their environments, while those that stubbornly insist on the maintenance of long-established practices unique to the organization tend to “collapse.”11 The adoption of a network approach to bureaucratic organization is prevalent in contemporary American state and local government.12

What is a network organization? First off, network organizations require the regular interaction of individuals in a variety of positions and with a wide range of different organizations — e.g., other local, state, national, public and private organizations. Thinking back to the bureaucratic model for a second, one could say that there were two dimensions to bureaucracy — the vertical (power and authority) and the horizontal (equal communication across similar positions). In network approaches to organization, there are multiple dimensions of interaction, and there are few fixed bureaucratic relationships; this is because the character of the network is dependent on circumstances existing at any given time. Communication organizes itself at one point in time around a hub of positions or of knowledge — i.e., the persons or organizations that possess or control relevant knowledge.

Actions taken by network organizations are based on knowledge acceptance in relation to organizational will or goals. Action is oftentimes informally initiated and is referred to as swarming – the near simultaneous movement by individuals or organizations to accomplish a goal. Network organizations are so loosely and flexibly organized that the clear command and control exercised by an organizational elite — a common feature often criticized in the bureaucratic model — is often not tenable. The flexibility and looseness of an organization is both its strength and weakness. Weaknesses arise with respect to holding specific subunits or persons accountable for their work. On the side of strengths, a network organization that has highly professional and ethical employees and reliably follow-through on commitments made to other members of the network can be exceptionally effective.13

Network organizations are a critical component of the innovative approach emerging in 21st century democratic governance;14 although, due caution must be observed in establishing and maintaining networks and in assuring collaborative effort quality over time.15 Responsive public administration must be aware of private sector adaptations and be willing to engage in public-private partnerships in an increasing number of areas such as green technologies, telework options for employees, and archival database sharing and joint or collaborative analysis.16

9.E – Knowledge, Skills and Abilities of the 21st Century Administrator

Government’s need for people with diverse sets of knowledge, skills and abilities means that no matter your specialty, a career in state and local public administration is likely an option. Good governance at all levels of government requires the education, training and skills of a wide array of backgrounds in areas as varied as physical science, social science, law, medicine, education, engineering, agriculture, criminology and linguistics, to name but a few. If you are interested in public administration and state and local government service as a career, it is possible to pursue educational goals directly related to your own area(s) of interest and personal passion — and, most likely, state or local government public administration will have a place for you in the years ahead. The building and governing of sustainable states and local communities will require professionals with a whole host of skills and knowledge for maintaining a vibrant local economy, becoming a steward of the natural environment, and promoting social equity.

In this regard, because new forms of knowledge are emerging at a rapid pace, public service professionals must be committed to life-long learning and networking. This adaptability will continue to be of critical importance in the coming decade. In the past, bureaucratic organizations valued this type of professionalism, but stultifying hierarchical command and control structures had a devaluing effect. Traditional bureaucracy has a clear tendency to constrain the behavior of bureaucrats rather than fostering their growth, and the inhibiting the development of personal responsibility and good judgment borne of active networking with peers in other organizations (public and private and non-profit alike). In the administrative governance paradigm described in this chapter, professionalism and a commitment to life-long learning are valued and rewarded because they foster innovation and the adaptability of thought and actions needed to develop, promote, and preserve plans, public policies, and public programs which enhance the sustainability of our communities and promote the adaptability of our states.

The ability to acquire relevant new knowledge and to determine its utility in the governance process is a multi-fold enterprise. First, governance in our democratic setting necessitates efficacious communication between administrators, elected officials, and citizens in order to determine the full meaning and value of the new knowledge in question. Administrative governance as we have described it this chapter plays a crucial role in the initiation and maintenance of this three-way dialogue. Second, the networked communication among similarly trained administrators in other jurisdictions collectively assesses the knowledge value of information, clarifying its validity and relevance to the particular state or local government in question. Finally, communication is a two-way process between a sender and a receiver of communication. An important governance role for administrators is to create dialogue with client stakeholders and elected officials in a manner that builds and empowers rather than erodes their sense of efficacy.17 In the administrative governance process, state and local government public administrators are both “doers” and “facilitators” who help others become doers.

A clear distinction between “administrators” and “elected officials” must be made here. State and local government administrators must be proficient leaders and executives, but they are not empowered to lead in the same way as elected officials. Good governance requires that public administrators convince others, through active networking, of the virtue of their solutions to problems — even though this networking activity may not always follow the established ways of doing business. Just as elected officials sometimes seek to convince voters of needed change, administrators use the public forums available to them — e.g., legislative testimony and public hearings, workshops and sponsored conferences — to demonstrate their own type of leadership in the governance process. Within their respective agencies, state and local government public administrators act as executives, directing their personnel towards large goals and seeking to develop interagency ties that will provide needed resources to promote effective current and future administrative governance.

9.F – Women and Minorities in Public Administration

In the 19th century, public administrative offices were often used by elected officials to reward their political supporters. A system of patronage inordinately benefited the dominant political force of the time — namely, white men. Despite the development of professional public administration, the new civil service systems remained notably biased against ethnic and racial minorities, and against women. While the 1950s and 1960s witnessed critical national and state legislation dealing with civil rights and equal employment opportunity, substantial barriers to equal employment and equitable promotion persist nonetheless. So-called glass ceilings —barriers against advancement to executive positions within state and local bureaucracies18—remain a significant obstacle to promotion up the ranks. These barriers to advancement are often a function of both managerial bias in the promotion and evaluation process, and reflect systematic biases that have become codified into the administrative structure.

Even more noxious and persistent has been the “gendering” of certain professions within public administration. The most identifiable example of this process was the notion that secretarial and management assistant staff positions were viewed as “female jobs.” Similarly in law enforcement agencies women were systematically excluded from jobs in patrol divisions because such work was seen as a man’s job. The area of cultural values and beliefs has proved to be the most difficult obstacle to overcome in the further advancement of women into the managerial ranks in state and local government public administration. In many jurisdictions, women have sustained claims of sexual harassment against those who perpetrated impermissible actions; however, many other legal actions taken by women seeking to redress their inequitable treatment have proven extremely difficult to bring to successful conclusion.

Minorities have long faced serious challenges in gaining equal employment opportunity. Historic discrimination against minorities in state and local administration remains a serious challenge to diversifying administrative employment. While great strides towards equal treatment have been made in the law, much work remains for people carrying out discretionary actions in hiring and promotional decisions that are based on the true merit of an individual as opposed to considerations of race, ethnicity and gender. Despite the obstacles facing them, women and minorities have contributed greatly to the building of the 21st century administrative systems needed to create sustainable states and communities. Glass ceilings are beginning to shatter — women have taken many notable positions as leaders in public administration. Contrary to the uninformed concerns and blatant stereotypes of white males of an earlier generation, women and minorities have regularly proven to be amongst the most effective and vocal leaders in administration today and making critically important contributions to the governance process.

9.G – E-Government

Creating sustainable governance is perhaps the principal challenge of the 21st century. Sustainability does not occur in isolation, but rather takes place in a competitive environment —while one state or community is attempting to create stable and livable conditions, other states and communities are competing for resources and for the attention of sustainable, clean industries. In this competitive environment, state and local governments frequently find themselves acting in an entrepreneurial way. A major part of being entrepreneurial in the current setting is streamlining governance.19 E-government plays an important role in this streamlining process.

One example of the power of e-government concerns new efficiency in managing paperwork. In the past, private industries interested in locating plants and offices in a particular state or local region were negatively impacted by bureaucratic red tape — the seeming mountain of legal paperwork and multitude of permitting involved in attempting to pursue economic development. The time lag between the filing of paperwork and the winning of ultimate approval is said to have driven away countless private industries and entrepreneurs that sought more lucrative business climates.

Revolutionary changes in information technology in the 1980s and 1990s led to more accessible, more affordable, and faster computing systems, forever altering the interface between state and local government public administration and their business community clientele. Increasingly, state and local government public administration has moved toward what is called an e-government model. Using Internet capability, e–government makes use of on-line forms and processing that reduces unnecessary face time between administrative staff and private industry and small business representatives. This same process has also streamlined the process of requesting and issuing permits and approvals, thus reducing the costs to investors seeking to develop in a particular state or local area.

E-government frees up administrators to complete other important tasks in the pursuit of sustainable development. More attention can be devoted to unique cases, and in the process improving the quality of administrator-client relations. With more time made available, administrators conduct outreach efforts to actively promote business relocation and development in their states and communities. Additionally, the improved computing network system attracts and retains Generation Y workers and citizens in urban areas. The continued improvement and development of the seamless administration-client interface of e-government is an important part of sustainability in 21st century governance.

9.H – Volunteers, Non-Profits and Administration

Governing within the paradigm of sustainability poses challenges to the manner in which administrative governance had been conceptualized previously. Until quite recently, the function of administration has been thought of as an insular activity carried out by trained professionals. Administrative governance was something that government did for or to citizen clients. There was a sense that administrators were experts who required little guidance beyond the strictures of statute, ordinance or common law. Citizens were seen as largely passive players in the modern governance process.

Recent developments have led administrators to actively recruit community volunteers to work along with administrative agencies.20 Take, for instance, the need to elicit volunteers in light of demographic changes in society that are fast approaching – namely, the oldest members of the Baby Boomer cohort are soon to enter their 60s. Many of these well-educated individuals were organizational leaders in the public and private sector and fulfilled critical roles in building the governance and private sectors. As these individuals retire, they are taking with them highly valuable knowledge, skills and abilities not easily replaced. The well-educated and highly motivated Generation X-ers (the generation following the Baby Boomers) is relatively small, lacking the sheer number of people needed to fully serve in critical administrative governance roles. Adding further to the problem, administrative costs are rising significantly, and as the Boomers age, the costs of employee benefits have increased dramatically. In an atmosphere characterized by both budgetary shortfalls and mounting debt, requesting additional resources to fully meet administrative goals is not likely to be rewarded with new allocations of state or local government resources. Under these circumstances “doing more with less” is the name of the game. Considering all of these factors in combination, scholars and practitioners realize that sustainable governance is not solely an administrative enterprise — it is quite clearly a genuine community enterprise.

In recognition of these circumstances, in the early 1990s President Bill Clinton promoted community-based volunteerism through his AmeriCorps initiative, a policy designed to bring a greater number of young people into a broader spectrum of volunteer community and public service activities, with the hope that some involvement in one’s youth would lead to a lifelong commitment to volunteering as these youth mature into adulthood. Along with pre-existing programs such as Volunteers in Service to America, Learn and Serve America, and the Senior Corps, AmeriCorps is part of the Corporation for National Service. The AmeriCorps program is particularly noteworthy because volunteers work through a network of nonprofit organizations delivering public goods and services. Non-profit organizations are effectively serving important roles either once fulfilled by administration or are supplementing insufficient administrative resources.

Incorporating volunteers into administrative enterprise is both rewarding and challenging. Volunteers often bring the community closer to administration, and vice versa. Administrative governance is positively served through keeping a finger on the pulse of the community through a network of volunteers. In the case of retired volunteers, administrators often note that they are among the hardest working individuals in their office, showing up on time and expending considerable energy performing critical tasks such as answering phones, dealing with clientele, and filing paperwork. It has been observed that — well-versed in etiquette — older volunteers often put clients at ease and are very effective at obtaining needed information to best solve clients’ dilemmas. Volunteers may also bring with them the tremendous enthusiasm of youth as they learn new skills and seek to help others. For example, AmeriCorps involvement in reading programs has demonstrated the role that volunteer enthusiasm can play in accomplishing the goal of adult literacy. The same is also true in environment-related programs that have young volunteers planting trees, repairing stream flows, and restoring lost indigenous species habitats.

Relying on volunteers in the administrative governance process also proves challenging. Unlike paid employees, volunteers often need to be motivated in unique ways. They generally need to feel a sense of purpose while carrying out their work, and their efforts to improve governance must be recognized in ways meaningful to them. Volunteers may indeed offer administrative agencies their time and skills, but they also require time and attention as well. If they feel ignored or underappreciated, volunteers often rapidly disengage. A downfall associated with relying on volunteers is that administrators tend to derive a false sense of their own capacity when goals are accomplished without additional full time staff. When this occurs agencies and political leaders may under-invest in full time human resources, placing agencies at future peril. All difficulties aside, however, there is no doubt that volunteerism continues to have a vital place in the functioning of state and local government administration.

9.I – Historical Trends in State and Local Employment

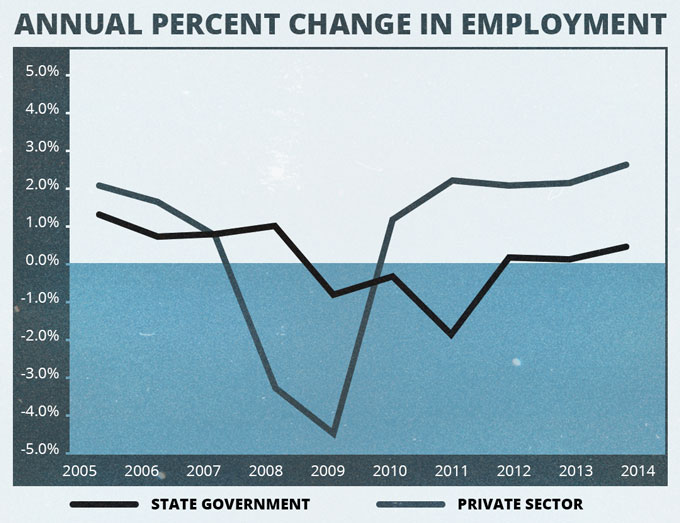

Over the last 25 years, the story of state and local government employment has been one of growth in scale and scope alike. While variations exist in state-by-state comparisons and across local jurisdictions, government employment at the state level grew by 35 percent overall and local government employment increased by over 48 percent. By comparison, national government employment actually decreased by approximately four percent between 1982 and 2004. However, the 2009 Great Recession took its toll on the number of state government workers due to budget cutting, however the process of recovering cut positions has begun. A recent study by the Council of State Governments found:21

- “From August 2008 to December 2014, a majority of states—31—added state government jobs.

- Colorado added the greatest number of positions (21,700), followed by Kentucky (18,500) and California (13,800).

- State government employment shrunk the most in Louisiana—by 24,800 positions—followed by Georgia, with a loss of 15,200, and New York, with a loss of 14,500.

- Over the same period, private sector employment grew by 4.1 million positions, or 3.6 percent.”

These employment trends become even more meaningful when considering the average number of clients served by state and local civilian employees. Clearly, variation exists across state governments, but on average the ratio of citizens to state employees has decreased from approximately 62:1 in 1982 to 58:1 in 2004. The ratio means that in 2004, for instance, for every state employee there were roughly 58 citizens. At the local level, the ratio declined from roughly 25:1 in 1982 to 21:1 in 2015. For individuals considering employment at the state and local level, the trend indicates that employees have — on average — greater time per client, thus increasing the probability of greater personal attention and increased effectiveness. By contrast, the ratio of population to national employees has moved in the opposite direction

Workplace diversity is an important issue in state and local government employment. While state variation exists, on average the proportion of women in state and local government employment has increased from 41 percent in 1981 to nearly 58 percent in 2015. Additionally, the proportion of state employees identifying themselves as black is 14 percent in 2015 compared to 9 percent in the private sector. Self-identified Hispanic employees in state government is 9 percent compared to 17 percent in the private sector. Asian employees are rough similar in the private and state government sectors at 5 percent. Being aware of how well community diversity is represented in government remains an important consideration.

| Private Sector | State Government | |

|---|---|---|

| Average salary | $53,420 | $50,461 |

| Weekly hours | 43.7 | 41.9 |

| Age (mean) | 41 | 45 |

| Married | 54% | 58% |

| Female | 41% | 58% |

| Educational Attainment | Private Sector | State Government |

|---|---|---|

| Less than HS | 11% | 3% |

| HS | 38% | 24% |

| Associates Degree | 12% | 13% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 28% | 32% |

| Master’s Degree | 8% | 18% |

| Professional Degree | 2% | 6% |

| Doctoral Degree | 1% | 4% |

| Race and Ethnicity | Private Sector | State Government |

|---|---|---|

| White | 78% | 76% |

| Black | 9% | 14% |

| Asian | 5% | 5% |

| Other | 7% | 5% |

| Hispanic | 17% | 9% |

| Immigrant | 20% | 10% |

Table 9.1 Comparing State Government Employees with the Private Sector

In terms of employment trends, clientele service, and salaries, the state and local government picture has looked increasingly rosy over the last quarter century, but all of these data must be considered carefully. First, there has been an increase in the percentage of employees at the state and local level who are part-time workers. Part-time workers are often ineligible for many of the benefits associated with full-time employment. From the managerial perspective, however, the flexibility engendered through managing part-time workers, in essence, brings workers into the workplace on needs-only basis, thus increasing organizational efficiency. In addition to the growth of part-time employment at the state and local level, private sector contractors play a much larger role in state and local government work. In some cases, private contractors have taken over the functions of government previously managed by full- or part-time state and local government employees.

9.J – Salaries in State and Local Government

Analyzing state government payrolls compared to the private sector offers insight into the general trends in employee investment. Using data from the U.S. census Bureaus annual American Community Surveys from 2009-2012, the average private sector employee earned $53,420 a year compared to $50,461 for state government workers (see Table 9.1). While compensation levels differ greatly across states, state employees are on average slightly below their private sector counterparts.

Salaries have risen over the last quarter century in real dollar terms. When studying salaries from a diversity perspective, women are still paid substantially less than men. White employees still make noticeably more money than minority employees. In trend analysis, it is evident that the salary trends for population sub-groups are paralleling one another — in studying median salaries at the state and local level of government as a whole, there does not seem to be any movement towards greater convergence or equity in pay. Pay and benefit equity vary across state and local government serving as an incentive to attract the highly qualified and diverse workforce needed in public service. A lack of diversity in public employment tends to parallel unresponsive state and local government, particularly problematic in a period of time necessitating the strong civic community linkages that build an inclusive, innovative, and sustainability promoting society.

9.K – Focus on State and Local Employment: Where Do They Work? What Do They Get Paid?

Bureaucracy is a tool of government. Earlier sections in the chapter illustrate the growth of state and local bureaucracy and the rise of a diverse workforce. But an important purpose of this book is to help readers figure out the current focus of state and local government and where they might become contributing players in governance. Therefore, a quick look at the top ten sectors for administrative employment in state and local government and a general look at the top ten average salaries is in order at this point in the chapter.

The greatest area of employment at the state level is in the higher education sector. Instructor and professors are only one aspect of higher education, of course. Administrators, buildings and grounds specialists, clerical staff, teaching and research assistants, student employees, and a whole host of other personnel play a significant role in higher education. After higher education, corrections — which deal with the incarceration and community supervision of convicted individuals — are the second largest state employment sector. Nearly ten percent of state employees across the country work in corrections. Public health and welfare are prominent employment sectors, as is street and highway management. Financial administration deals with the proper allocation and accounting of state revenues — in essence, the maintenance of fiscal accountability. Natural resource management accounts for roughly three percent of state employment.

Average salaries are determined by studying total annual payroll in state employment sectors and dividing by the number of employees in that sector. It is admittedly a rough measure, but nonetheless provides interesting evidence. On average, the top salaried positions at the state level tend to be in science- and engineering-intensive professional fields. Electric power, air transportation, transit and sewerage are employment sectors that usually entail substantial engineering and physical science education. If the reader wishes to pursue a well paying position in state government, it would behoove them to consider pursuing math and science education. Training in criminal justice or law is also of great value in terms of well-compensated state employment.

Elementary and secondary education employs nearly 55 percent of all local government employees. Police protection is the second largest employer, but at a drastically smaller portion of the local government sector — less than seven percent of local government employees work in police protection services. Other prominent employment sectors in local government are fire protection, public health, parks and recreation, and public welfare. General government administration accounts for three percent of local government positions.

As with the state level salaries, the best compensated positions in local government are in sectors requiring a strong science and/or engineering background. Criminal justice and legal training will also improve chances of gaining employment in high salaried local government jobs. Fire protection increasingly requires a solid understanding of knowledge in the areas of criminal justice, Homeland security, emergency medical assistance, chemistry, biology, physics, health care, engineering, and material science, to name but a few of the areas of expertise. Education is not in the top ten of highest paying jobs in this sector at either the state or the local level.

9.L – Administration, Governance, and Innovation

When governments are first developed, leaders define institutions. Later, it is institutions that define and often constrain leaders. At the state and local level, for elected leadership, age old-institutional constraints shape and limit the choices possible. In many ways, elected leaders’ position in state and local governance has weakened. Governance is the regular decision-making, implementation, and evaluation of policies designed to ensure that public goods are effectively managed or delivered to citizens. The process of election and re-election also limits state and local elected leaders, often drawing them towards more partisan decision-making as they seek voter support and campaign contributions.

Administrative leaders do not face the same pressures as elected officials do. First, administrative leaders are chosen based on their tenure in administrative ranks and merit-based performance. Merit relates to the knowledge, skills, and demonstrated abilities of an individual in relation to a job description within an administrative organization. Second, administrative leaders are hired based on demonstrated merit, usually evaluated in relation to objective analysis of formal training, past experience, and performance on a job-related examination. Third, administrators are generally granted tenure, a limited property right to employment so long as their job performance remains satisfactory. For these reasons, administrators are often less distracted in the governance process; constrained by statutory and common law, administrators are usually guided by principles of justice in their decision-making rather than by partisanship.

Theoretically, administrators represent the interests of no single person or group of people; instead, they pursue politically neutral goals. In the process of serving the public interest, however, administrators come into contact with individuals and groups of individuals who have unique needs. In some cases, groups of individuals may attempt to influence administrative governance through appeals to elected administrators or through other forms of political pressure. In either case, administrators are ultimately driven to pursue the public interest, guided by a solid knowledge and understanding of statutory and common law.

Statutes and common law are frequently silent on how day-to-day administrative governance should occur, and on what types of decisions should be made. In political decision-making, sources of guidance might be voter or campaign contributor preferences or even partisanship. In administrative decision making, legal precedents, administrative capacity, and a professional code of ethics are key sources of guidance in the governance process. Additionally, administrators function closely at the client-level, close to the consumer of a public service, placing them in good position to assess the intent of elected governing institutions in relation to statutory and common law constraints; administrators are often keenly aware of how governance decisions promote or detract from judicious outcomes.

Not all administrators serve so closely to citizen consumers. Over the course of a career, administrators are promoted from positions closely tied to a customer base into positions of senior administrator authority. The group with greater authority is generally composed of well-educated, long-serving, and tightly networked individuals. Education is a product of formal training melded with years of practical experience. Long career service can be both beneficial and distracting, however. It is beneficial to the degree that administrators have a sense of what has worked and what has not worked in past attempts at policy innovation and governance. It is potentially distracting in the sense that long service is often associated with a more conservative or defensive stance, and resistance to pursue important and justifiable risks in governance — risks capable of producing positive results for communities. Finally, long-serving administrators have had time to meet people, lots of people, and to cultivate trust and mutual respect through regular interaction. Administrators develop professional networks with elected leaders, interest and community group leaders, and other administrators. A solid network involves interactions with individuals and groups from different levels of government on an inter-jurisdictional basis. Senior level administrators often have access to critical governing networks, greater knowledge, and more experience with day-to-day governing than do most politicians.

9.M – Bureaucracy and the Core Dimensions of Sustainability

Often decried by critics, state and local bureaucracy is very well-positioned to advance the core dimensions of sustainability. Bureaucracy has both the formal and informal structure to meet a complex set objectives effectively and efficiently. While traditional formal bureaucratic structures can be viewed as hierarchically organized, the day-to-day operations of bureaucrats tend increasingly towards network structures. Individual state and local government administrators form around and connect with information/knowledge hubs to solve problems of the moment, to meet pressing objectives. Additionally, the rise of e-government has streamlined bureaucratic processes and reduced costs at a time when costs are rising and demands on government are growing exponentially. Finally, bureaucracy is well-situated to meet the needs of sustainable governance because it is one of the few forms of government institutions that is designed to govern the commons, and whose basic premises focus on equitable distribution of public resources for the individual and collective benefit. Elected branches of state and local government are frequently heavily influenced by the demands of a winning coalition, and the individuals and groups who gain the most influence over elected leaders or candidates for public office are the leading forces within those electoral coalitions. Finally, unlike the elected branches, public administration has a long-term commitment to creating a diverse workforce — a workforce that reflects the nature of a community in the grandest sense of the word.

Looking at the four major objectives of sustainability, as outlined in the first chapter of this book, it should be noted that the principles of sustainable governance are embedded in the basic principles and goals of numerous familiar bureaucratic agencies. Elected officials have, in many instances, created public institutions to meet the pressing issues of a society. Social objectives are often met through public health offices, social workers, K-12 schools and universities, corrections agencies, labor bureaus, fish and wildlife agencies and a host of other bureaucratic offices. In the current economic crises facing state and local governments across the country, politicians may propose increased investment in human capital and the building of strong social capital, but it is often the work of bureaucrats at the street level that turns those often high-minded goals into real world realities. If these real world efforts to promote the enhancement of human and social capital in the service of community sustainability are not being done by public servants operating by themselves, it is the work of thousands upon thousands of hard working, highly motivated volunteers who support the efforts of bureaucrats working in a variety of human capital-related initiatives and enterprises.

Sustainable economic activity is one of the core dimensions of sustainability and sustainable governance. Sustainability demands that the marketplace of the future offers high quality products produced with and made use of with low environmental impact and purchased at a reasonable cost. In many cases, this means that important trade-offs must be considered and managed effectively. Locally-grown food and locally-produced goods and services require that state and local workplace dynamics and market conditions must be understood and managed to ensure the goals of sustainability are achievable in a way that is least intrusive on individual economic freedom and liberty, but that simultaneously protects the interests of the broader community in both the short and long-term. Politicians may come and go, but it is state and local bureaucrats who will serve in regulatory agencies over the long-haul, getting to know the “regulated” — i.e., the industry actors in their communities — and carefully balancing the needs of the regulated with the needs of the greater society. The networked bureaucrats in these agencies will have access to their peers in other state and local governments, and efforts to disseminate “best practices” and “evidenced-based” programs promotive of economic sustainability will be promoted first by these people, and subsequently the best ideas will be endorsed and advocated by elected officials in due course.

Environmental sustainability objectives are inextricably wedded to issues of economic sustainability. Again, bureaucratic agencies, often operating independently or semi-independently of the political process, who manage natural resources will be in forefront of public policy development. State departments of forestry, state offices of environmental quality and workplace safety, water quality offices, fish and wildlife agencies and parks and recreation offices are examples of agencies seeking to meet the goals of environmental sustainability. The work of these agencies is often multi-agency in character, and increasingly involves the use of multi-party collaborative processes designed to find ways in a particular state or in a specific geographic area how productive economic activity can be sustained without undue harm occurring to environmental assets.

Finally, institutional objectives such as facilitating higher population density and reduced urban sprawl in metropolitan areas are often dealt with through the interaction between a multitude of municipal, county, and state planning offices. Bureaucrats and the bureaucratic agencies in which they work have the know-how, skills and time available to conduct the long range planning processes required to anticipate changes that could call into question the sustainability of communities. Sustainability demands that state and local governments provide for adequate consideration of the needs of communities today and in the more distant future, and keep in mind the dictum that the current generation must not leave a diminished range of options to achieve prosperity, environmental health and social equity to the next generation. The infrastructure redesign for the development of renewable energy systems, for instance, will require a century or longer commitment to a better way of providing energy to permit our way of life to endure. The planners of state and local government will play a critical role in the education of elected officials and the general public alike as to the need for such long-range investment in a sustainable future.

Exercises

Bureaucracy: What Can I Do?

When many students in political science think about post-graduate studies they typically think about law school. However, there are many other opportunities such as Master programs in Public Administration, Public Affairs and Public Policy. Learn more about these type of programs at the National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration (NASPAA) website: www.naspaa.org

You can also learn more about public service and public administration through NASPPA’s networking site on Linkedin:

Linkedin: http://www.linkedin.com (MPA/MPPs)

NASPPA has also created a MPA/MPP Channel on the video sharing site YouTube where you can find interviews with prominent graduates as well as student created videos:

YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/mpampp

9.N – Sustainable Bureaucracies

This chapter has discussed many initiatives, policies and programs of state and local bureaucracies that contribute to sustainability. These include the use of e-government, networking, life-long learning for personnel, a diverse workforce that represents citizen diversity, and the strategic use of volunteers. State and local administrators are also reorganizing and reinventing government to improve program efficiencies, to harness resources outside government in the service of public policy goals, and to better facilitate the input of state-level interests, private sector groups, and the general public.22 The move to share bureaucratic decision-making power with citizens and personnel in the lower reaches of organizational hierarchies, to embrace collaborative public–private and public–private–NGO (non-governmental organization) partnerships, and to reform dense rule structures and hierarchy as necessary components of an efficient and/or accountable public administration is occurring across a broad range of policy areas, including community policing,23 tax administration,24 education,25 elements of the federal Job Opportunities in the Business Sector (JOBS) program,26 rural,27 and public.28 This effort has been called collaborative governance or cooperative governance, and could include watershed councils, granges in rural locations, and neighborhood councils in urban areas.

The propensity to adopt alternative institutional arrangements premised on decentralization, collaboration, and citizen participation is especially pronounced in the environmental and natural resources policy world.29 Regulatory negotiation, which actively involves a broad range of stakeholders in the specification and implementation of regulations, has become more widely used for pollution control. The federal Environmental Protection Agency has developed the Common Sense Initiative (CSI) in league with corporate America, state regulators, national environmentalists, and locally based environmental justice groups. Their goal is to encourage innovation by providing flexibility and to rationalize existing regulatory rules for each industrial sector through the use of a place-by-place approach to achieving pollution control standards.30 EPA’s Project XL (Excellence and Leadership), announced in 1996, features a series of pilot projects that follows the lead of CSI. Project XL and authorizes site-based stakeholder collaboratives “…to allow industrial facilities to replace the current regulatory system with alternative strategies if the result achieve[s] greater environmental benefits.”31 While there is still much to be learned about collaborative governance concerning where it will be most effective, it may hold much promise in solving difficult problems at state and local levels.

9.O – Conclusion

The chapter began by discussing the negative stereotypes many Americans have concerning bureaucracy and bureaucrats. While there are many reasons for these negative stereotypes, ultimately they may have much to do with what Barry Bozeman calls the “inherently controlling” nature of bureaucracy:32

Unless all action is voluntary, coordination of activity requires control. Most of us do not like being controlled, even for the collective good. Even worse, bureaucracy strives (even if it does not always succeed) to deliver even-handed treatment and to administer policies in a disinterested manner, showing no favoritism.

However, as this chapter has sought to communicate, while state and local bureaucracy does often involve control by seemingly “disinterested” administrators, state and local bureaucrats are also key actors in the ultimate achievement of sustainable communities.

While the bureaucratic model may be a thing of the past in American politics, good governance will always be an ongoing goal. State and local government administration are evolving into increasingly sophisticated enterprises at a rapid pace. Community needs are changing and increasing in scope — and as a consequence administrators in state and local government need to find ways to meet these needs while keeping costs of operation as low as possible. The use of e-government, as mentioned earlier, has increased efficiency and effectiveness of government administration greatly. A cooperative relationship within and across organizations is making better use of human and fiscal resources. The demand for person-to-person service has forced innovation — and the strategic use of retirees and youthful volunteers has become a prominent element in modern governance as a consequence. Employment at the state and local level is and will continue to improve in the years ahead. Bureaucrats, in the truest sense, play an essential role in the organization and administration of our state and local governments.

Terms

Bureaucracy

Civil servants

Collaborative governance

Cooperative governance

E-government

Glass Ceiling

Governance (see also “collaborative” and “cooperative” governance)

International City/County Management Association (ICMA)

Lifelong learning

Merit-based performance (civil service)

Network approaches

Patronage

Red tape

Reinventing government

Tenure

Exercises

Discussion Questions:

1. What are the historic trends in state and local government employment in terms of numbers employed and demographics (race, gender)? Do you think these trends will continue into the future?

2. What is the role of state and local bureaucracy in promoting sustainable communities? Can you think of some specific examples?

3. How about the role of “red tape” in bureaucracy? Is it always a negative phenomenon, or is it important in preventing corruption and maintaining even-handed treatment of citizens?

4. What are some of the new skills and abilities required of state and local administrators in the 21st century?

Notes

1. M. Weber [H.H. Gerth and C.W. Mills, trans.], From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958).

2. R. Agranoff, and M. McGuire, Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2003).

3. See H.G. Fredericksen, G. Johnson, and C. Wood, “The Changing Structure of American Cities: A Study of the Diffusion of Innovation,” Public Administration Review 64 (2004), 320-330.

See also T.H. Poister, and G. Streib, “Elements of Strategic Planning and Management in Municipal Government: Status after Two Decades,” Public Administration Review 65 (2005): 45-56.

N.M. Riccucci, M.K. Meyers, I. Lurie, and J.S. Han, “The Implementation of Welfare Reform Policy: The Role of Public Managers in Front-Line Practices,” Public Administration Review 64 (2004): 438-448.

4. H. Bacot, and J. Christine, “What’s So ‘Special’ About Airport Authorities? Assessing the Administrative Structure of U.S. Airports,” Public Administration Review 66 (2006): 241-251.

5. M. Potoski, “Designing Bureaucratic Responsiveness: Administrative Procedures and Agency Choice in State Environmental Policy,” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 2 (2002): 1-23.

6. W.M. Lafferty, ed., Governance for Sustainable Development. The Challenge of Adapting Form to Function (Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2004).

7. C.Bowling, C. Cho, and D.S. Wright. “Establishing a Continuum from Minimizing to Maximizing Bureaucrats: State Agency Head Preferences for Governmental Expansion—A Typology of Administrator Growth Postures, 1964-1998,” Public Administration Review 64 (2004): 489-499.

8. For good sources on this phenomenon, see:

M.Poole, R. Mansfield, and J. Gould-Williams, “Public and Private Sector Managers Over 20 Years: A Test of the Convergence Thesis,” Public Administration 84 (2006): 1051-1076.

A. Sapat, “Devolution and Innovation: The Adoption of State Environmental Policy by Administrative Agencies.” Public Administration Review 64 (2004): 141-151.

C.W. Thomas, Bureaucratic Landscapes: Interagency Cooperation and the Preservation of Biodiversity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003).

9. H. B. Milward and K.G. Provan, “Governing the Hollow State,” J-PART Journal Public Administration: Research and Theory 10(2000): 359-379.

D.G. Frederickson and H.G. Frederickson, Measuring the Performance of the Hollow State (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2007).

10. M. Bowens, “Street-Level Resilience,” Public Administration Review 66 (2006): 780-781.

11. J. Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (New York: Viking, 2005).

12. F.S.Berry, R. Brower, S. Choi, W.X. Goa, H. Jang, M. Kwon, and J. Word. “Three Traditions of Network Research: What the Public Management Research Agenda Can Learn from Other Research Communities.” Public Administration Review 64(2004): 539-552.

13. M.P. Mandell, ed., Getting Results through Collaboration: Networks and Network Structures for Public Policy and Management (Westport, CT: Quorum Books, 2001).

14. W.J. Kickert, E.H. Klijn, and J. Koppenjan, eds., Managing Complex Networks: Strategies for the Public Sector (London: Sage Publications, 1997).

C.W. Lewis, “In Pursuit of the Public Interest,” Public Administration Review 66(2006): 694-701.

J. Nalbandian, “Politics and Administration in Council-Manager Government: Differences between Newly Elected and Senior Council Members,” Public Administration Review 64(2004): 200-208.

15. L. O’Toole, and K. Meier, “Desperately Seeking Selznick: Cooptation and the Dark Side of Public Management Networks,” Public Administration Review 64 (2004), 681-693.

S. Page, “Measuring Accountability for Results in Interagency Collaboratives,” Public Administration Review 64(2004): 591-606.

16. G. Noble, and R. Jones, “The Role of Boundary-Spanning Managers in the Establishment of Public-Private Partnerships,” Public Administration 84(2006): 891-917.

17. See contributions to a conference on workplace discrimination held at Rice University in May of 2000 collected into the edited volume: Dipboye and Colella (eds.), Discrimination at Work: The Psychological and Organizational Bases (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2005).

18. R. Connell, “Glass Ceilings or Gendered Institutions? Mapping the Gender Regimes of Public Sector Worksites,” Public Administration Review 66(2006): 837-849.

19. D.F. Norris, and M.J. Moon, “Advancing E-Government at the Grassroots: Tortoise or Hare?” Public Administration Review 65(2005): 64-75.

D.M. West, “E-Government and the Transformation of Service Delivery and Citizen Attitudes,” Public Administration Review 64(2004): 15-27.

20. B. Gazley, and J. Brudney, “Volunteer Involvement in Local Government after September 11: The Continuing Question of Capacity,” Public Administration Review 65(2005): 131-142.

21. J. Burnett, “Trends in State Government Employment,” The Council of State Governments. URL: http://knowledgecenter.csg.org/kc/content/state-government-employment

22. D. Osborne, and T. Gaebler, Reinventing Government (New York: Basic Books, 1993).

23. D.H. Bayley, Police for the Future (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994).

24. M.K. Sparrow, Imposing Duties: Government’s Changing Approach to Compliance (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994).

25. D. Matthews, Is There a Public for Public Schools? (Cleveland, OH: The Kettering Foundation, 1996).

26. E. Bardach, and C. Lesser, “Accountability in Human Services Collaboratives — For What? and to Whom?” J-PART: Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 6(1996): 204-205.

27. See the thoughtful contributions collected in Beryl Radin et al., New Governance for Rural America: Creating Intergovernmental Partnerships (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1996).

28. J. Walters, Measuring Up: Governing Guide for Performance Measurement (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 1997), pp. 160-162.

29. M.E. Kraft, and D. Scheberle, “Environmental Federalism at Decade’s End: New Approaches and Strategies,” Publius 28(1998):131–146.

30. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “The Common Sense Initiative: A New Generation of Environmental Protection,” EPA Insight Policy Paper (August, 4 1994 [EPA 175-N-94-003]).

31. U.S. Congress, “An Assessment of EPA’s Reinvention,” A Report by the Majority Staff of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives (September, 1996), p. 10.

32. B. Boseman, Bureaucracy and Red Tape (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2000), pp. xi-xii.