Chapters

Chapter 6: Legislatures

6.A – Introduction

A legislature is an officially elected assembly formed to make laws for a political unit such as a nation, a state or a local government. The genesis of legislatures traces back to the medieval period when “Althing” (a Nordic word for ‘general assembly’) was established in Iceland and a uniform code of laws was proclaimed. In more contemporary times, there are various types of legislative forms, including the two most common categories of legislatures — the presidential style systems featuring separation of powers and parliamentary-style systems featuring integration of powers.1 As discussed in the previous chapter, in political systems reflecting a separation of powers philosophy of governance, a policy adoption vs. policy administration and implementation dichotomy exists separating the legislative branch and the executive branch; in line with this demarcation of responsibilities governmental powers are fairly clearly separated in law and in practice;2 in contrast, in political systems reflecting an integration of powers philosophy of governance members of the executive branch are selected from and are held directly accountable to the legislative branch.3 In the U.S., state legislatures are presidential-style bodies which are primarily in charge of making laws of general-purpose and universal application for the respective states with governors being responsible for the “faithful execution” of state laws. At the local level BOTH general-purpose governments and single-purpose governments are present. The former provides a wide range of services and serves a diversity of functions, while the latter carries out a specific function such as education, the provision of utilities, the irrigation of farmlands, or the provision of transportation services, for example. There are a variety of legislative structures used in local governments, including boards of county commissioners, city councils, school district boards, and a wide variety of more specialized elective boards and commissions that will be discussed in this chapter.

Learning Objectives

The topics covered in this chapter include:

-

- The functions of legislatures.

- Noteworthy Variation in the ways state legislatures operate.

- Legislatures in general-purpose local governments.

- Legislatures in single-purpose local government.

- The critical legislative role in promoting sustainability.

6.B – State Legislatures

All the U.S. states have a popularly elected legislative branch, and each state constitution specifies the essential features of the composition and method of organization of state legislative bodies. State legislatures are the primary lawmaking bodies of American government, and they are, generally speaking, quite similar in structure to the U.S. Congress. The legislature in all cases is a multi-member body of popularly elected representatives. In forty-nine states the legislature is divided into two houses, generally a Senate and a House of Representatives, just as is the U.S. Congress. Only Nebraska features a unicameral (one chamber) legislature. The “upper house” (Senate) is usually significantly smaller than the lower house, which in most states is called the “House of Representatives.” Senators are most often elected for four-year terms, but some states elect their Senators every two years. State representatives usually are elected for two-year terms. In many states, constitutional term limits control the number of terms – consecutive or otherwise – which a legislator is allowed to serve. Most states dictate that each legislative electoral district will elect only one representative and only one senator. However, eight states do allow multi-member districts wherein voters elect more than one representative for the lower house of the state legislature.

Nearly all of the American states adopted the bicameral legislature in major part because they wished to allow landowners a major voice in government disproportionate to their number in the electorate. Senators were once elected by county or groups of counties as opposed to population, in a manner similar to the U. S. Senate’s apportionment of two Senators per state, regardless of the size of its population. This apportionment of seats in the upper chamber allowed residents in rural and sparsely populated areas of a state to exercise significantly more influence than urban residents within American state legislatures. In 1962 (Baker v. Carr) and again in 1964 (Reynolds v. Sims), however, the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear cases wherein it was argued that the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution required that the principle of “one person, one vote” should apply to both houses of American state legislatures. It was reasoned by lawyers arguing for a fundamental change in the organization of state legislatures that the U.S. Congress organized membership around a principle of representation by geography because it is a federal system in which the individual states pre-existed the establishment of the United States of American. In the case of the U.S. states, however, they are each unitary governments wherein all citizens, regardless of where they reside (city, suburb, or rural area) are entitled to equal representation.

The U.S. Supreme Court determined in these landmark cases that both chambers of American state legislatures must be based upon population alone. The initial result of these decisions was that state legislatures redrew their upper chamber legislative district lines to reflect population, causing many more legislators to be representing urban areas in upper chambers of American state governments. These legislative districts must be redistricted every ten years when the U.S. Census is taken to assure that they conform to the equal representation [“one person, one vote”] standard as closely as possible. While the manifest intent of redistricting is to ensure equal representation in government, the process of drawing legislative district lines is the responsibility of state legislatures and tends to become highly politicized and partisan in nature in those states which do not establish an independent, bipartisan body to carry out redistricting. In fact, in a number of states’ district lines are commonly redrawn to maximize the strength of the majority party and weaken the minority party in a process known as gerrymandering. This process entails concentrating the minority party’s voters in as few districts as possible and distributing the majority party’s voters in such a way that they are likely to prevail in as many legislative districts as possible.

As the process of gerrymandering indicates, political parties play a very important role in state legislatures. The majority party typically organizes the election of the leader of the lower house (the House Speaker in most cases), and in most states, the leader of the upper house (typically the Senate Majority Leader) is put into office on the basis of a partisan vote. The party leadership in both chambers generally appoints legislators to their committee assignments, designates committee chairs in the case of the majority party, and typically controls floor activity fairly tightly. As a result of these decisions influenced greatly by the majority political party, a relatively small number of key legislators in control of a legislative house typically dominate the agenda and content of bills heard during a legislative session.

The powers of state legislatures universally include modifying existing laws and making new statutes, developing the state government’s budget,4 confirming the executive appointments brought before the legislature,5 impeaching governors and removing from office other members of the executive branch.6 All these powers and associated activities can be assigned into one of the three major functions performed by state legislators singularly and state legislatures collectively: representation, lawmaking, and balancing the power of the executive (or oversight).

6.B.I – Representation:

A major role of a state legislator is to represent the needs and concerns of the people residing in her and his legislative district. Since each legislator is responsible to a relatively small number of constituents coming from a specific geographical area, they are able to address concerns that are not as apparent to statewide officials such as the Governor or State Attorney General. This attention to localized needs can lead to intense debate over conflicting values when, for example, representatives of rural, conservative communities are forced to compromise with the interests represented by urban legislators representing liberal constituents.

Legislators also represent the interests of their constituents beyond the formal law-making process. Legislators are often enlisted to make a phone call or write a letter on behalf of a citizen who needs help getting a personal issue addressed or expedited by the state bureaucracy. Research conducted by political scientists has shown that such constituency service pays significant dividends at re-election time, with voters looking favorably on helpful legislators by either volunteering for campaign work or contributing money to re-election campaigns. Key components of sustainability as addressed in the literature include the development of civil society, active representation by elected officials, and the maintenance of continuous interaction between citizens and representatives. In this regard, how legislators interact with their constituents is an important part of the promotion of sustainability in those communities where efforts to promote sustainability require some level of state approval or financial support.

The process of representation works at two distinct levels. First, at an individual representative’s level, there is a connection between the legislators and the districts from which they are elected. And secondly — as a unit — the legislature pursues policies that reflect the statewide interests and preferences of citizens.7 The process of representation, from the perspective of political scientists, consists of four principal components: maintaining communications with constituents; demonstrating policy responsiveness by reflecting the needs of one’s constituency in one’s votes on bills and budgets; affecting the allocation of resources across elective districts; and providing individualized service to constituents.8

Another way to think about representation is in terms of the socio-demographic and gender composition of state and local legislative bodies. Many observers argue that legislative bodies should, to some significant extent, mirror the public they represent — in terms of race, ethnicity, gender and such — to adequately represent the public at large. In this regard, it should be noted, “in the past, political scientists have convincingly demonstrated that race and gender matter in political representation.”9 Research has consistently shown that in state legislatures “Black legislators sponsor a higher number of Black interest measures and female legislators sponsor a higher number of women’s interest measures” when compared to white men.10

In general, “female state legislators are reported to be more liberal than men, even when controlling for party membership, and female state legislators are more concerned with feminist issues than their male counterparts.”11 Research has also found that black women legislators are similar to white women legislators in terms of their support for women’s issues — such as affirmative action, comparable worth, public support for daycare, and many other issues. As with black male legislators, black women legislators tend to be strong supporters of minority target policies such as education, health care, and job creation-oriented economic development.12 However, research has also found that women legislators are generally as likely as their male counterparts to achieve passage of the legislation they introduce, whereas black legislators are significantly less likely than their white counterparts to get legislation they introduce enacted into law.13

In terms of the actual representation of women and minorities in state and local legislatures, there has been a noteworthy increase in numbers over the last several decades.14 The Center for American Women and Politics, an organization that systematically tracks the number of women in elected office, reports the following in terms of women serving in state legislatures across the country (see Table 6.1):15 In 1971, women comprised 4.5 percent of state legislators and by 2018 they make up 25.4 percent of legislatures. Since 1971, the number of women serving in state legislatures has more than quintupled.

For example, “Presently, there are 27 states and the District of Columbia that have African American mayors. The cities’ populations range from less than 300 to over 2 million people.”16Some of the explanations given for the lower levels of women and minorities in state and local legislative bodies include cultural, institutional and situational explanations.17 Cultural explanations would include state political culture, which would affect the attitudes toward women and minorities in politics held by citizens and elites.18 Some argue that states with more traditional political cultures deeply entrenched in history — e.g., the southern states — may well view politics as a man’s world or the domain of white Americans in comparison to states with more progressive political cultures — e.g., the northeastern or western states (see Table 6.2).19 For women, this political culture aspect of their political environment can have three specific adverse consequences:20

First, women may not run for office because they do not believe it to be appropriate. Second, women may not be highly recruited to run for political office because party officials and other political elites are biased against female candidates. Or third, even women who are not socialized into passive gender roles and who do run despite unsupportive elites face unsympathetic voters at the polls…

A second explanation of low levels of women and minorities in state and local legislatures concerns the institutional arrangements determining electoral success. For example, states with high levels of incumbents re-elected to office would allow for fewer seats being open to competition.21 In addition, states with multi-member districts versus states with single-member districts tend to have racially, ethnically and gender-wise more diverse legislatures.22 It has been argued that voters are more willing to support women and minorities when there are multiple choices to make in an electoral setting. A third explanation for lower levels of women and minorities in state and local legislative bodies concerns situational factors such as financial resources, educational levels, and occupation, which all affect the ability to run for office and to establish important political networks to support successful campaigns. In addition, “…women tend to start much later in politics than men, are less likely to be recruited than men, and have more political opportunities closed to them than men.”23

| YEAR | % OF TOTAL |

|---|---|

| 1987 | 15.7% |

| 1989 | 17.0% |

| 1991 | 18.3% |

| 1993 | 20.5% |

| 1995 | 20.6% |

| 1997 | 21.6% |

| 1998 | 21.8% |

| 1999 | 22.4% |

| 2000 | 22.5% |

| 2001 | 22.4% |

| 2002 | 22.7% |

| 2003 | 22.4% |

| 2004 | 22.5% |

| 2005 | 22.7% |

| 2006 | 22.8% |

| 2007 | 23.5% |

| 2008 | 23.6% |

| 2009 | 24.3% |

| 2011 | 23.7% |

| 2012 | 23.7% |

| 2013 | 24.2% |

| 2015 | 24.3% |

| 2016 | 24.4% |

| 2018 | 25.4% |

Table 6.1 Women in State Legislatures

| STATE: | % WOMEN |

|---|---|

| Arizona | 40.0% |

| Vermont | 40.0% |

| Nevada | 38.1% |

| Colorado | 38.0% |

| Washington | 37.4% |

| Illinois | 34.5% |

| Maine | 33.9% |

| Maryland | 33.5% |

| Oregon | 33.3% |

| Rhode Island | 31.9% |

| STATE: | % WOMEN |

|---|---|

| Wyoming | 11.1% |

| Oklahoma | 13.4% |

| Louisiana | 12.9% |

| West Virginia | 13.0% |

| Mississippi | 14.2% |

| Alabama | 14.9% |

| South Carolina | 15.0% |

| Tennessee | 15.9% |

| Kentucky | 15.9% |

| North Dakota | 18.4% |

Table 6.2 States with Highest and Lowest Percentage of Legislators — 2018

Those that favor legislative diversity have proposed a variety of electoral mechanisms to increase the number of women and racial minorities serving in state and local legislative bodies. Some have suggested the broadened adoption of term limits because the current re-election rate of incumbents is very high, while others have suggested the creation of majority Black or Latino districts by carefully drawing election district lines to favor minority districts.24 However, this latter approach to the promotion of diversity in legislative bodies was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Miller v. Johnson 515 U.S. 900 (1995) and Shaw v. Hunt 517 U.S. 899 (1996).

6.B.II – Lawmaking:

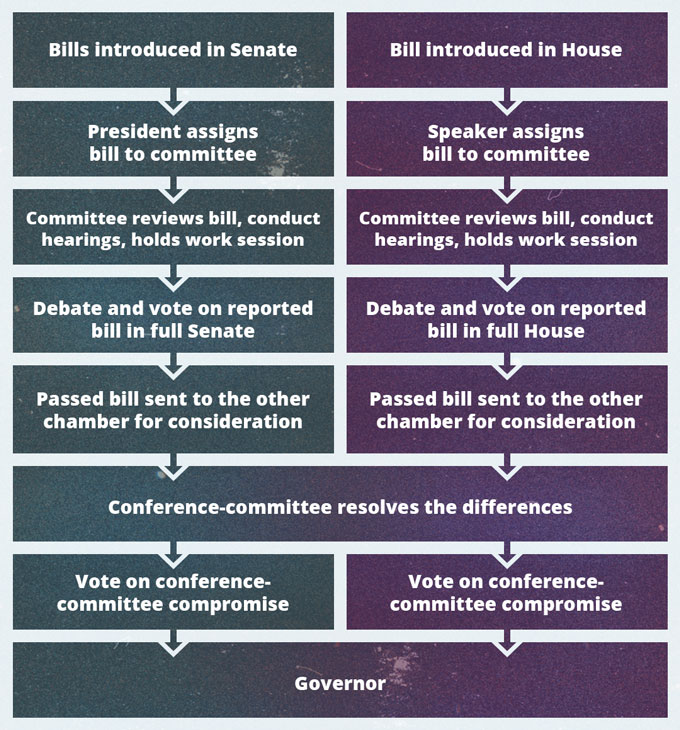

Policymaking is accomplished through the introduction and passage of bills that eventually become law. The process usually begins with the introduction of bills in either house of the legislature. While bills must be introduced by a legislator, they usually have been crafted by a governor, an attorney general, a public agency, or an interest group. Once a legislator chooses to introduce the legislation other representatives and senators can sign on as co-sponsors, increasing the chance that the bill will survive scrutiny in legislative committees. New bills are referred to policy committees in their chamber of origin. The committee chair decides whether or not to hold a hearing on the bill, and whether or not to hold a committee vote on it. Bills are frequently amended in committee before they are voted out. If the vote in committee is favorable, the bill is forwarded to a rules committee that makes decisions on which bills are placed on the calendar of the chamber to be heard. Bills can be amended once more on the floor, and if passed they are sent to the other chamber for its consideration. If the second chamber amends the bill and passes it, then members of both chambers go to a “conference committee” to determine if the differences between the two versions of the bill can be reconciled. If a compromise is achieved, the new bill is sent back to the floor of the Senate and House for a final vote. If the conference committee bill is approved in both houses of the legislature it is then sent to the governor where it will be signed into law, vetoed, or remain unsigned. If a bill is vetoed by the governor, it can return to the legislature for a possible veto override by a “supermajority” (usually two-thirds vote) in both chambers. If a governor neither signs nor vetoes a bill, it will become law in two-thirds of the states; in the remaining third of the state’s inaction by the governor is referred to as a “pocket veto” and the bill dies (see Figure 6.1). Another way for a bill to become law in some states is a legislative referral, an action by the legislature and the governor that places the legislation on the ballot for voters to decide approval or disapproval.

6.B.III – Balancing the Power of the Executive:

In a separation of powers governmental system, the three branches of government are expected to share power rather than allowing one branch to have disproportionate power over the others. This arrangement of governmental powers has been commonly known as the checks and balances system, a particular vision of governmental design enshrined in the U.S. Constitution by the Founding Fathers. The third principle role a legislature plays, therefore, is balancing the power of executive. This balancing role can be achieved by performing legislative oversight that involves the legislature’s review and evaluation of selected activities of the executive branch and exercising the “power of the purse” – that is, carrying out the responsibility of developing the state budget. In American government, no funds can be spent by an executive agency unless an express allocation is made by a legislative enactment (the budget is set in a bill enacted into law just as any other statute). A main reason for state legislatures to conduct oversight is that “it has a duty to ensure existing programs are implemented and administered efficiently, effectively, and in a manner consistent with legislative intent.”25 The job of exercising legislative oversight is carried out by a combination of standing committees, select committees, and task forces.26 In Ohio, for example, three such important oversight committees are the Joint Legislative Committee on Health Care Oversight, the Joint Legislative Committee on Medicaid Technology and Reform, and the Turnpike Legislative Review Committee composed of members of both chambers of the state legislature.27 Common forms of oversight activities include periodic review of administrative rules, the enactment of sunset provisions in legislation, the passage of legislation calling for studies into particular problems or existing programs, the engagement in active fiscal oversight and the provision of advice to executive agencies, and the granting of consent to gubernatorial appointments.

State legislatures assume the role of oversight in order to assure that laws are being implemented efficiently and effectively in the manner originally intended by the legislature. The legislature often evaluates the executive branch’s policy and programs through the employment of policy analysts and auditors working for legislative committees. These analysts and auditors attempt to assess progress toward the objectives and goals of policies and agencies reflecting the original intent of the legislation. The use of legislative policy analyses and audits has been credited with increasing efficiency and effectiveness in state government, thereby saving taxpayers money and improving program performance.

Legislatures periodically review the rules and regulations employed by the executive branch in order to determine whether the intent of the law is being realized. This review process often accompanies budget hearings and ultimate budget approval for state agencies. If the legislature determines that an agency’s rules and regulations are unsatisfactory, they can insist that the rules be modified or suspended; in some cases the legislature retains the right to discontinue support for a program if, in its judgment, the agency in question is not following legislative intent or is determined to have failed to meet the goals set for it. Some states have determined that the “legislative veto” (an action of constraint upon a public agency by a legislature after legislation has been placed into law) is an unlawful violation of the separation of powers. Even without explicitly revoking a rule or regulation by direct action of the legislature after a law has been duly enacted, the legislature can exert great influence over previously enacted statutes by reducing the agency’s budgetary allotment in order to encourage more faithful compliance with legislative wishes.

Sunset laws are those pieces of legislation featuring a built-in expiration date for a statute. Legislation of this nature allows the legislature to review, implement changes in, or terminate a program simply by not renewing an existing law. While sunset laws ensure the bureaucracy will be subjected to periodic review, the process of review is often time-consuming, can be quite costly, but only rarely results in the termination of a program. Bowman and Kearney state in this regard, “sunset reviews are said to increase agency compliance with legislative intent . . . [but] only 13 percent of the agencies reviewed are eventually terminated, thus making termination more of a threat than an objective reality.”28

The review and control of state (and federal “pass-through”) funds is one of the most significant powers exercised by state legislatures. By holding the purse strings at both the state and federal level, the independence of the legislative branch ensures that the bureaucracy and executive branch agency leadership remains quite dependent upon legislative support. Thus, oversight is permitted and the executive branch is prevented from becoming unresponsive to lawmakers and their constituency. Furthermore, by reviewing and controlling federal funds given to the state through intergovernmental programs such as interstate transportation, environmental regulation, Medicaid, etc., legislators are aware of how that federal government transfer money is being spent by the executive branch. Importantly, citizens who wish to know how those federal funds are being spent in this state and localities can contact their legislator and request an accounting. This type of constituent service is an important part of legislative representation. In the area of the promotion of sustainability, your state legislator should be able to provide you with specific, timely information concerning what federal and state programs are in place to address sustainability concerns.

6.C – Variation Among State Legislatures

State legislatures vary across the country in terms of their official names, the length of time they stay in session, the number of legislative districts they use, their party affiliations, and the way it operates. For example, state legislatures in most states are called “Legislatures;” for example, the Alabama Legislature, the Oklahoma Legislature, the Nevada Legislature, and Montana State Legislature are common names. In some states, however, the state legislature is referred to as the “General Assembly,” such as the Virginia General Assembly and the Pennsylvania General Assembly. In the states of Massachusetts and New Hampshire the term “General Court” is used to designate the state legislative branch. For bicameral state legislative bodies, the upper house is most typically called the “Senate,” but the terms used for the lower house vary widely across the states (see Table 6.3). Historically, most of the original American colonies were governed by unicameral legislative systems until a gradual process of adoption of bicameralism started and picked up momentum.29 The bicameralism movement was based on respect for the British model of bicameralism of the House of Lords and the House of Commons.30 Today, as noted previously, virtually all (49) state legislatures in the U.S. are bicameral, and only Nebraska has maintained a unicameral legislature (see Table 6.4).

| STATE | BOTH BODIES | UPPER HOUSE | LOWER HOUSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Alaska | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Arizona | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Arkansas | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| California | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| Colorado | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Connecticut | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Delaware | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Florida | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Georgia | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Hawaii | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Idaho | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Illinois | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Indiana | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Iowa | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Kansas | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Kentucky | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Louisiana | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Maine | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Maryland | General Assembly | Senate | House of Delegates |

| Massachusetts | General Court | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Michigan | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Minnesota | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Mississippi | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Missouri | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Montana | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Nebraska | Legislature | – | – |

| Nevada | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| New Hampshire | General Court | Senate | House of Representatives |

| New Jersey | Legislature | Senate | General Assembly |

| New Mexico | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| New York | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| North Carolina | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| North Dakota | Legislative Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Ohio | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Oklahoma | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Oregon | Legislative Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Pennsylvania | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Rhode Island | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| South Carolina | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| South Dakota | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Tennessee | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Texas | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Utah | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Vermont | General Assembly | Senate | House of Representatives |

| Virginia | General Assembly | Senate | House of Delegates |

| Washington | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

| West Virginia | Legislature | Senate | House of Delegates |

| Wisconsin | Legislature | Senate | Assembly |

| Wyoming | Legislature | Senate | House of Representatives |

Table 6.3 State Legislative Houses

| INDICATORS | UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURE | BICAMERAL LEGISLATURE |

|---|---|---|

| Representation, responsiveness to the majority, responsiveness to diverse and minority interests, responsiveness to powerful interests | A citizen has one representative, favors rule by the majority, deeper understanding of all various interests, ‘almost heaven’ for special lobbyists | A citizen has two respective representatives, bicameral deliberation, gives voice to disparate points of views, hard for lobbyists to affect legislative activities |

| Legislative Stability | Not necessarily volatile | Maybe more stable |

| Procedural Simplicity | More | Less |

| Authority of the Legislators | Authority of a legislator is not shared | Authority of a legislator is shared |

| Concentration of Power within the Legislature | Concentrates power in one house | Concentrates power in a few members |

| Quality of Decision-Making | Promotes quality by deliberate, careful decision-making | Promotes quality by slowing decision making, by having a second thought, and by requiring approval by two chambers |

| Efficiency and Economy | Maybe more efficient in conducting its business and less costly to operate | May require more cost, but also generate more benefits |

Table 6.4 Unicameral Legislature and Bicameral Legislature

Another difference between state legislatures concerns time status — some states have full-time legislatures meeting frequently on an annual basis, while other states have part-time legislatures that meet biannually and infrequently. Many rural states tend to have a part-time legislature, while the states with larger populations are likely to have full-time legislatures. Texas is an exception in this regard, with the second-largest population and a part-time legislature.31 The National Council of State Legislatures has categorized the 50 state legislatures into three basic groups: full-time legislatures, hybrid legislatures, and part-time legislatures. Full-time legislatures “…require the most time of legislators, usually 80 percent or more of a full-time job.”32 These legislatures typically feature large staffs and their members are usually paid salaries sufficient to make a decent living. Full-time legislatures are typically found in the states with highly urbanized populations (see Tables 6.5 and 6.6).

| FULL-TIME | HYBRID | PART-TIME |

|---|---|---|

| California | Alabama | Georgia |

| Florida | Alaska | Idaho |

| Illinois | Arizona | Indiana |

| Massachusetts | Arkansas | Kansas |

| New Jersey | Colorado | Maine |

| Michigan | Connecticut | Mississippi |

| New York | Delaware | Montana |

| Ohio | Hawaii | Nevada |

| Pennsylvania | Iowa | New Hampshire |

| Wisconsin | Kentucky | New Mexico |

| Lousiana | North Dakota | |

| Maryland | Rhode Island | |

| Minnesota | South Dakota | |

| Missouri | Utah | |

| Nebraska | Vermont | |

| North Carolina | West Virginia | |

| Oklahoma | Wyoming | |

| Oregon | ||

| South Carolina | ||

| Tennessee | ||

| Texas | ||

| Virginia | ||

| Washington |

Table 6.5 State Legislature Types

| LEGISLATURE TYPE: | AVERAGE TIME SPENT ON JOB: | AVERAGE COMPENSATION: | AVERAGE NUMBER OF STAFF: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-type | 84% | $82,358 | 1,250 |

| Hybrid | 74% | $41,110 | 469 |

| Part-time | 57% | $18,449 | 160 |

Table 6.6 Legislative Job Time, Salary and Staff Size—2015

Legislators elected to hybrid legislatures “…typically say that they spend more than two-thirds of a full-time job being legislators” and their salaries are noticeably higher than part-time legislatures but somewhat lower than those of members of full-time legislatures.33 Salaries are typically not sufficient to make a living on legislative pay alone, so additional outside employment is common among these state lawmakers. Hybrid legislatures tend to have intermediate-sized staffs, and they are typically found in states with moderate-sized populations.

Lawmakers in part-time legislatures generally spend “…the equivalent of half of a full-time job doing legislative work. The compensation they receive for this work is quite low and requires them to have other sources of income in order to make a living.”34 Part-time legislatures are often called “citizen legislatures” and are most often found in rural states with relatively small populations. The legislative staff available to lawmakers in these states are typically few in number.

State legislatures are also diverse in terms of their size and their party composition. Legislators prefer policies that favor the preferences of voters in individual districts, and thus the size of a district matters when considering the implications of certain policies. Table 6.7 shows the number of seats in state upper and lower houses. While some economists have argued that larger legislatures are less efficient and prone to conflict because “…cooperation cannot be sustained in large legislatures,” there has been little empirical research on this topic.35

In terms of partisan alignment, in 2016 Republicans gained a sizable majority of all legislative seats and won their biggest legislative victory in more than a decade. In 2016, Republican majorities took control of both houses in 30 state legislatures and Democratic majorities control both houses in 10 states. In the other 10 states, the two parties split control of the state legislature, with one party having supremacy in one house and the other party having control of the other chamber (see Table 6.8).36

| STATE | SEATS IN SENATES | SEATS IN HOUSES |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 35 | 105 |

| Alaska | 20 | 40 |

| Arizona | 30 | 60 |

| Arkansas | 35 | 100 |

| California | 40 | 80 |

| Colorado | 35 | 65 |

| Connecticut | 36 | 151 |

| Delaware | 21 | 41 |

| Florida | 40 | 120 |

| Georgia | 56 | 180 |

| Hawaii | 25 | 51 |

| Idaho | 35 | 70 |

| Illinois | 59 | 118 |

| Indiana | 50 | 100 |

| Iowa | 50 | 100 |

| Kansas | 40 | 125 |

| Kentucky | 38 | 100 |

| Louisiana | 39 | 105 |

| Maine | 35 | 151 |

| Maryland | 47 | 141 |

| Massachusetts | 40 | 160 |

| Michigan | 38 | 110 |

| Minnesota | 67 | 134 |

| Mississippi | 52 | 122 |

| Missouri | 34 | 163 |

| Montana | 50 | 100 |

| Nebraska | 49 | Unicameral |

| Nevada | 21 | 42 |

| New Hampshire | 24 | 400 |

| New Jersey | 40 | 80 |

| New Mexico | 42 | 70 |

| New York | 62 | 150 |

| North Carolina | 50 | 120 |

| North Dakota | 47 | 94 |

| Ohio | 33 | 99 |

| Oklahoma | 48 | 101 |

| Oregon | 30 | 60 |

| Pennsylvania | 50 | 203 |

| Rhode Island | 38 | 75 |

| South Carolina | 46 | 124 |

| South Dakota | 35 | 70 |

| Tennessee | 33 | 99 |

| Texas | 31 | 150 |

| Utah | 29 | 75 |

| Vermont | 30 | 150 |

| Virginia | 40 | 100 |

| Washington | 49 | 98 |

| West Virginia | 34 | 100 |

| Wisconsin | 33 | 99 |

| Wyoming | 30 | 60 |

Table 6.7 Seats in Senates and Houses

| STATE | DEMOCRATS Senate Seats | REPUBLICAN Senate Seats | INDEPENDENT Senate Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 8 | 26 | 1 |

| Alaska | 6 | 14 | – |

| Arizona | 12 | 18 | – |

| Arkansas | 11 | 24 | – |

| California | 26 | 14 | – |

| Colorado | 17 | 18 | – |

| Connecticut | 21 | 15 | – |

| Delaware | 12 | 9 | – |

| Florida | 14 | 26 | – |

| Georgia | 17 | 39 | – |

| Hawaii | 24 | 1 | – |

| Idaho | 7 | 28 | – |

| Illinois | 39 | 20 | – |

| Indiana | 10 | 40 | – |

| Iowa | 26 | 24 | – |

| Kansas | 8 | 32 | – |

| Kentucky | 11 | 27 | 1 |

| Louisiana | 14 | 25 | – |

| Maine | 15 | 20 | – |

| Maryland | 32 | 14 | – |

| Massachusetts | 34 | 5 | – |

| Michigan | 11 | 27 | – |

| Minnesota | 39 | 28 | – |

| Mississippi | 20 | 32 | – |

| Missouri | 8 | 24 | – |

| Montana | 21 | 29 | – |

| Nebraska | Nonpartisan Election | Nonpartisan Election | Nonpartisan Election |

| Nevada | 10 | 11 | – |

| New Hampshire | 14 | 10 | – |

| New Jersey | 24 | 16 | – |

| New Mexico | 25 | 17 | – |

| New York | 31 | 32 | – |

| North Carolina | 16 | 34 | – |

| North Dakota | 15 | 32 | – |

| Ohio | 10 | 23 | – |

| Oklahoma | 8 | 39 | – |

| Oregon | 18 | 12 | 2 |

| Pennsylvania | 19 | 31 | – |

| Rhode Island | 32 | 4 | 1 |

| South Carolina | 17 | 28 | – |

| South Dakota | 8 | 27 | – |

| Tennessee | 5 | 28 | – |

| Texas | 11 | 20 | – |

| Utah | 5 | 24 | – |

| Vermont | 19 | 9 | 2 |

| Virginia | 19 | 21 | – |

| Washington | 24 | 25 | – |

| West Virginia | 16 | 18 | – |

| Wisconsin | 14 | 19 | – |

| Wyoming | 4 | 26 | – |

| STATE | DEMOCRATS House/Assembly Seats | REPUBLICANS House/Assembly Seats | INDEPENDENT House/Assembly Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 33 | 70 | – |

| Alaska | 16 | 23 | 1 |

| Arizona | 24 | 36 | – |

| Arkansas | 35 | 64 | 1 |

| California | 51 | 32 | – |

| Colorado | 34 | 31 | – |

| Connecticut | 86 | 64 | – |

| Delaware | 25 | 16 | – |

| Florida | 39 | 81 | – |

| Georgia | 61 | 117 | – |

| Hawaii | 44 | 7 | – |

| Idaho | 14 | 56 | – |

| Illinois | 71 | 47 | – |

| Indiana | 29 | 71 | – |

| Iowa | 43 | 57 | – |

| Kansas | 28 | 97 | – |

| Kentucky | 50 | 46 | – |

| Louisiana | 42 | 61 | 2 |

| Maine | 78 | 69 | 4 |

| Maryland | 91 | 50 | – |

| Massachusetts | 123 | 34 | – |

| Michigan | 46 | 61 | – |

| Minnesota | 61 | 72 | – |

| Mississippi | 47 | 74 | – |

| Missouri | 45 | 117 | – |

| Montana | 41 | 59 | – |

| Nebraska | Unicameral | Unicameral | Unicameral |

| Nevada | 17 | 25 | – |

| New Hampshire | 160 | 239 | 1 |

| New Jersey | 52 | 38 | – |

| New Mexico | 33 | 37 | – |

| New York | 104 | 43 | – |

| North Carolina | 45 | 74 | 1 |

| North Dakota | 23 | 71 | – |

| Ohio | 34 | 65 | – |

| Oklahoma | 30 | 71 | – |

| Oregon | 35 | 25 | – |

| Pennsylvania | 84 | 119 | – |

| Rhode Island | 63 | 11 | 1 |

| South Carolina | 46 | 78 | – |

| South Dakota | 12 | 58 | – |

| Tennessee | 26 | 73 | – |

| Texas | 51 | 98 | – |

| Utah | 12 | 63 | – |

| Vermont | 85 | 53 | 12 |

| Virginia | 34 | 66 | – |

| Washington | 50 | 48 | – |

| West Virginia | 36 | 64 | – |

| Wisconsin | 36 | 63 | – |

| Wyoming | 9 | 51 | – |

Table 6.8 Party Affiliation in Legislatures Across the States — 2016

The number of bills introduced into legislatures and enacted into law also varies greatly across the American states. For example, 14,823 bills were introduced and 589 bills were enacted into law in New York in 2015. In stark contrast, there were only 391 bills introduced and 204 bills enacted into law in Wyoming in the same year. Comparisons are made with the bills introduced and enacted in 2015 regular sessions in Table 6.9.

| STATE | BILLS INTRODUCTIONS | BILLS ENACTMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 1,210 | 357 |

| Alaska | 575 | 48 |

| Arizona | 1,163 | 324 |

| Arkansas | 2,062 | 1,289 |

| California | 2,370 | 807 |

| Colorado | 682 | 364 |

| Connecticut | 3,202 | 261 |

| Delaware | 370 | 194 |

| Florida | 1,574 | 227 |

| Georgia | 955 | 312 |

| Hawaii | 2,894 | 190 |

| Idaho | 523 | 382 |

| Illinois | 6,534 | 483 |

| Indiana | 1,237 | 258 |

| Iowa | 1,851 | 143 |

| Kansas | 746 | 105 |

| Kentucky | 752 | 117 |

| Louisiana | 1,106 | 469 |

| Maine | 1,455 | 442 |

| Maryland | 2,234 | 495 |

| Massachusetts | 6,988 | 704 |

| Michigan | 1,890 | 269 |

| Minnesota | 4,605 | 80 |

| Mississippi | 2,620 | 347 |

| Missouri | 1,888 | 131 |

| Montana | 1,187 | 457 |

| Nebraska | 664 | 247 |

| Nevada | 1,013 | 556 |

| New Hampshire | 902 | 276 |

| New Jersey | 9,074 | 381 |

| New Mexico | 1,281 | 158 |

| New York | 14,823 | 589 |

| North Carolina | 1,634 | 300 |

| North Dakota | 854 | 484 |

| Ohio | 678 | 45 |

| Oklahoma | 2,112 | 398 |

| Oregon | 2,641 | 848 |

| Pennsylvania | 2,867 | 39 |

| Rhode Island | 2,399 | 423 |

| South Carolina | N.A. | 138 |

| South Dakota | 427 | 258 |

| Tennessee | N.A. | 1,007 |

| Texas | 6,276 | 1,323 |

| Utah | 1,520 | 477 |

| Vermont | 666 | 64 |

| Virginia | 1,919 | 774 |

| Washington | 2,365 | 297 |

| West Virginia | 1,607 | 262 |

| Wisconsin | 1,830 | 356 |

| Wyoming | 391 | 204 |

Table 6.9 Bills Introductions and Enactments in 2015 Regular Sessions

6.D – Legislatures in General-Purpose Local Government

General-purpose local governments, which include county governments, municipal governments, and town and township governments, provide a wide range of services that affect the day-to-day lives of citizens. Services such as police protection, road, street and bridge infrastructure, parks and recreation, and land use (zoning) are typical duties of general-purpose governments in the United States. These governments feature both an executive and legislative function, and the executive function is discussed elsewhere. This section focuses on the legislative role of general-purpose local governments whose legislative bodies are boards of county commissions, city councils, and town boards of aldermen or selectmen.

6.D.I – County Commissions:

Counties function primarily as the administrative appendages of a state, and thus they implement many state laws and policies (such as carrying out elections) at the local level. The central legislative body in a county government is commonly a board of “commissioners” or “supervisors.” Typically, a county commission meets in regular session monthly or bimonthly, and its legislative responsibilities encompass the enactment of county ordinances, the development, and approval of the county budget, and, in some states, the setting of certain tax rates.37

6.D.II – City Councils:

Municipal government in America originates from the English parish and borough system. The English parish was involved in both church service and road maintenance, while the English borough engaged in commercial and governmental affairs. These traditional aspects of civic society in England were gradually merged into a single entity and developed into the concept of municipality in the United States.38 In contrast to a county, which is an administrative appendage of a state, a city is considered a municipal “corporation” that can produce and implement its own local laws and public policy. For example, the City of New York creates its own sales tax, apart from the New York State sales tax created by the state government.39 The executive branch of city governments is generally organized into one of three basic forms: a mayor-council form, a city commission form, and a council-manager form. These executive structures are discussed in detail elsewhere. However the executive authority of the municipality might be organized, the legislative body provided for in each of these three basic forms is typically called a city council, and that legislative body exercises the power to make public policy.

Traditionally, members of most city councils were elected through at-large elections, a practice that often resulted in their becoming somewhat unresponsiveness to some groups in their jurisdiction. In recent decades city councils have tended to emphasize district elections, and as a consequence city councils have become considerably more diverse in terms of gender, race, and ethnicity than they were in the past. Today city legislative bodies are less white and less male and less business-dominated than they were in the past and feature many more African Americans, Hispanics, and women.

6.D.III – Town Boards:

Today, official town and township governments continue to operate in 20 states in three major regions (see Table 6.10).40 In terms of legislative process, many of these towns have a tradition of direct democracy through a “town meeting” wherein residents elect town officials, enact ordinances, and adopt a budget. Typically, all available voters are invited to provide input, offer amendments, and vote on township business. These types of local government legislatures are often found in smaller jurisdictions.

| REGIONS | STATES |

|---|---|

| New England | Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island |

| Mid-Atlantic | New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania |

| Mid-West | Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Kansas, Nebraska, and Missouri |

Table 6.10 Regions and States with Official Towns and Townships

6.D.IV – The Adapted City:

Research by Frederickson and Johnson has found that while almost all U.S. cities were initially established as either a council-manager or mayor-council form of government, they typically “adapt” to incorporate the best features of both systems. They found that over-time, cities with council-manager systems tend to adopt features of mayor-council systems “…to increase their political responsiveness,” and that cities with mayor-council systems tend to adopt features of council-manager systems “…to improve their management and productivity capabilities.”41 Frederickson and Johnson argue that these developments have led to a third form of municipal governance they call the “adapted city.” As emphasized in the introductory chapter regarding adaptation to change, this is a characteristic of institutional sustainability — the ability of cities to reform their governmental structures to promote economic and administrative efficiency, and to increase political responsiveness and civil society.

6.E – Legislatures in Single-Purpose Local Government

As their name implies, typical single-purpose local governments only have one principal function. These local government entities usually provide services that general-purpose local governments are either unwilling to perform or are incapable of performing.42 Special district boards and commissions and school district boards constitute the legislative bodies in single-purpose local governments.

6.E.I – Special District Boards:

A special district usually has a population of residents occupying a specific geographic area, features a legal governing authority, maintains a legal identity separate from any other governmental authority, possesses the power to assess a tax for the purpose of supplying certain public services, and exercises a considerable extent of autonomy.43 Special districts have been created for a variety of purposes; for instance, a watershed district aims at promoting the beneficial use of water and a rural hospital district works to maintain health care services to a sparsely populated area.44 In many areas of the country, a sanitary district strives to improve sewerage services,45 and a rural fire protection district focuses on providing fire protection through a combination of professional and volunteer firefighters.46 While the vast majority of the special districts in the U.S. perform a single function, a small proportion of them provides two or more services. Local government units known as county service areas in California, for example, provide police protection, library facilities, and television translator services in some areas of the state.

<<Photo 6-4>>

The category of special district governments includes both independent districts and dependent districts. For independent districts, the board members are generally elected by the public, but in some cases, members are appointed by public officials of the state, counties, municipalities, and town/townships that have joined to form special districts.47 Dependent districts are governed by other existing legislatures such as a city council or a county board. For instance, the County Service Areas noted above are dependent districts that are governed by their county boards of supervisors.48 The Oceanside Small Craft Harbor District in California is a subsidiary organ of the City of Oceanside, and the members of the Oceanside City Council also serve on the District’s board.49 To sum up, special districts are independent if the members of boards are independently elected or appointed for fixed term of office; special districts are dependent if they depend on another local government to govern them.50 However, they are governed, in their financial and administrative aspects special districts are all considered fiscally ‘independent’ because they exist as separate legal entities and exercise a high degree of fiscal and administrative independence from the general-purpose governments around them.51

6.E.II – School District Boards:

As a type of single-purpose local government, a school district serves primarily to operate public primary and secondary schools or to contract for public school services. Its legislative body is typically called a “school board”52 or a “board of trustees,”53 and the members of these boards can be either elected or appointed for fixed terms of office.54 Typically, the school board has five to seven members whose job it is to make policy (e.g., adoption of special programs, approval of grant applications, setting disciplinary rules, going to the public to request passage of school levies, etc.) for the school district. One major issue in policy decisions is the development and enactment of a school district budget.

School districts also consist of both independent and dependent units. Independent school districts are defined as local governments that are fiscally and administratively independent of other government entities, such as townships, municipalities, and counties. They can provide for and promote public education, but are not allowed to use their revenues on public goods other than education. Dependent school districts, in contrast, are not counted as separate governments because they are dependent on a ‘parent’ government that is capable of shifting public expenditure among various public goods.55 As of 2002, there were 15,029 public school systems in the United States, and of these 13,522 are independent school districts and the other 1,507 can be classified as dependent districts.56

Exercises

Legislatures – What Can I do?

Find out more about state legislatures by visiting the National Council of State Legislators (NCSL) website at: http://www.ncsl.org/ and their public participation website at: http://www.ncsl.org/legislators-staff/legislators/trust-for-representative-democracy/public-participation-and-confidence-in-the-leg541.aspx. The NCSL also has many educational materials located at their “Trust for Representative Democracy” project: http://www.ncsl.org/trust/index.htm.

Visit the International City Managers Association’s (ICMA) website to find out current issues confronting municipalities at http://icma.org and then use USA.Gov’s directory to locate your own county or city government websites at https://www.usa.gov/local-governments Go to your own local government’s website and see when city council or country commissioner public meetings are held and attend one. Former U.S. Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill once said “all politics is local,” go see for yourself what issues are confronting your own local governments.

6.F – Legislatures and Sustainability

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs has highlighted the critical importance of local governments, and hence local government legislative bodies responsible for making laws and ordinances, in the development of sustainable local governments. The authors of the department’s report issued in 2004 observe the following in this regard:

Because so many of the problems and solutions being addressed by Agenda 21 have their roots in local activities, the participation and cooperation of local authorities will be a determining factor in fulfilling its objectives. Local authorities construct, operate and maintain economic, social and environmental infrastructure, oversee planning processes, establish local environmental policies and regulations, and assist in implementing national and subnational environmental policies. As the level of governance closest to the people, they play a vital role in educating, mobilizing and responding to the public to promote sustainable development.57

In Governing Sustainable Cities, Evans et al. present a working framework for what factors contribute to community sustainability.58 These scholars suggest that sustainability is in major part a function of two community-based components: institutional capacity and social capacity. Institutional capacity is defined in terms of levels of commitment from government officials, the demonstration of political will, investment in staff training, technological mainstreaming, engagement in knowledge-based networks, and provision of legislative support for maintaining network connections. Similarly, social capacity is defined by the degree of inclusion in collective civic efforts of local citizen volunteers, news media, business establishments, representatives of industry, local universities, and local non-governmental organizations.59 Based on the possible combinations of institutional and social capacities, Evans and his colleagues identify four potential governance outcomes:60

- Dynamic governing – communities with ‘higher’ levels of social and institutional capacity have ‘high possibility of accomplishing sustainability-promoting policy outcomes.

- Active government – communities with ‘lower’ levels of social capacity, but ‘higher’ levels of institutional capacity have ‘medium or fairly high’ possibility for accomplishing sustainability-promoting policy outcomes.

- Voluntary governing – communities with ‘higher’ levels of social capacity, but ‘low’ institutional capacity, have ‘low’ possibility for accomplishing sustainability-promoting policy outcomes.

- Passive government – communities with ‘low’ levels of both institutional and social capacity have little possibility of achieving a sustainable future.

These findings are similar to the argument of Costantinos to the effect that the active support of the state and local government legislative bodies is a critical predictor of sustainable states and communities. This support is accomplished by:

…developing systems whereby public opinion can be made known to members of the legislature, including (the level of) support to develop their constituency, developing the capacity of the legislature to draft and introduce legislation or amendments to existing legislation on specific subjects.61

6.G – Conclusion

It is clear from the material discussed in this chapter that legislative forums in American state and local government represent a vast terrain of widely differing scales and scope of responsibility, traditions of normal operation, and extent of access to professional staff support. Whatever their current arrangements, traditions, and resources, however, it is beyond argument that the observations of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs are absolutely on target in maintaining the critical importance of the “governments closest to the people” in meeting the challenges of sustainability in our collective lifetimes.62 The evidence of global climate change, the accumulation of greenhouse gases, the extinction of species, the scarcity of natural resources, the decimation of forests, and the pollution of air and surface waters is no longer a matter of unsettled controversy, and the short time-frame for effectively coping with an endangered global ecological system requires all levels of government to become engaged in “dynamic governing” in service to sustainability.

In each of the chapters to follow it will be seen how the multiple actors – including state legislatures and local boards, commissions, and councils – are striving to perform their traditional duties plus take on new responsibilities for passing on a sustainable form of economic and social life to the next generation of Americans. The institutional and social capacities of our states and local communities will be tested in the coming decades, and there are signs that the identification of and dissemination of “best practices” in many sectors for a sustainable future will require the dedicated effort of legislators, public servants, civic groups, and ordinary citizens accepting their civic duty. This challenging work that lies ahead requires informed and active participants in the government processes most directly related to daily life. Some state legislatures such as those in California, Oregon, and Washington are taking the lead in promoting standards for automobile emissions, energy use and carbon sequestration that go beyond federal standards required by the Environmental Protection Agency, thereby challenging the authority of the federal government, while others are watching to see the results of those challenges. Many local government mayors (over 1,000 at this writing) are following the lead of Seattle’s Mayor Nichols and the U.S. Conference of Mayors in committing to the Climate Protection Agreement which sets out ambitious goals for reducing greenhouse gases and conserving energy consistent with the Kyoto Accords even though the United States is not a signatory to those international accords. These developments represent a hopeful beginning for the governments closest to the people rising to the challenges of sustainability facing each state government and each local community in the coming years.

Terms

Administrative rules

Checks and balances

Constituency service

County services area

Dependent (special) districts

General purpose governments

Gerrymandering

Independent (special) districts

Legislative oversight

Legislative referral

Parliamentary style systems

Presidential style systems

Select committees

Single purpose governments

Standing committee

Sunset provisions

Task force

Term limits

Exercises

Discussion Questions

1. According to this chapter, what are the major functions that legislatures play in state and local government?

2. What are some of the similarities and differences in how state legislatures operate?

3. Compare and contrast the roles and functions of general-purpose and single-purpose governments.

4. How can legislatures promote economic, social and ecological sustainability?

5. With respect to the city or town you consider to be your hometown, would characterize it as featuring passive government, voluntary governing, active government, or dynamic governing?

Notes

1. A. Lijphart, Parliamentary Versus Presidential Government (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

R.K. Weaver and B. A. Rockman, Do Institutions Matter? Government Capabilities in the United States and Abroad (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1993).

2. H.G. Frederickson and K. B. Smith, The Public Administration Theory Primer (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2003).

3. D. Woodhouse, Ministers and Parliament: Accountability in Theory and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

4. W. Clarke, W. “Divided Government and Budget Conflict in the U.S. States,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 23(1998): 5-22.

5. K.E. Hamm and R. D. Robertson, “Factors Influencing the Adoption of New Methods of Legislative Oversight in the U.S. States,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 6 (1981): 133-150.

6. M.J. Gerhardt, The Federal Impeachment Process: A Constitutional and Historical Analysis (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

7. A. Rosenthal, Heavy Lifting: The Job of the American Legislature (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2004).

8. K.L. Barber, “American Government and Politics,” American Political Science Review 77 (1983): 1039-1040.

M.E. Jewell, Representation in State Legislatures (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1982).

9. K. Bratton, “The Effect of Legislative Diversity on Agenda Setting: Evidence from Six State Legislatures,” American Politics Research 30 (2002): 115-142, p. 115.

11. E. Barrett, “The Policy Priorities of African American Women in State Legislatures,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 20 (1995): 223-247, p. 223.

14. K. Bratton and K. Haynie, “Agenda Setting and Legislative Success in State Legislatures: The Effects of Gender and Race,” Journal of Politics 61 (1999): 658-679, p. 658.

15. Center for American Women in Politics (Eagleton Institute, Rutgers University, 2008): URL: http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/Facts.html (accessed August 15, 2009).

16. National Conference of Black Mayors, Mayors of Cities with Populations over 50,000. URL: http://www.ncbm.org/members_of_NCBM.html (accessed August 15, 2009).

17. K. Arceneaux, “The Gender Gap in State Legislative Representation: New data to Tackle and Old Question,” Political Research Quarterly 54 (2001): 143-160.

18. D. Alexander and K. Anderson, “Gender as a Factor in the Attribution of Leadership Traits,” Political Research Quarterly 46 (1993): 527-545.

19. V. Sapiro, The Political Integration of Women (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1984).

S. Welch, “Women as Political Animals? A Test of Some Explanations for Male-Female Political Participation Differences,” American Journal of Political Science 21 (1977): 711-730.

20. K. Arceneaux, 2001, op. cit. (see reference 17), p. 145.

21. R. Darcy and J. Choike, “A Formal Analysis of Legislative Turnover: Women Candidates and Legislative Representation,” American Journal of Political Science 30 (1986): 237-255.

22. G. Moncrief, J. Thompson, M. Haddon and R. Hoyer, “For Whom the Bell Tolls: Term Limits and State Legislatures,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 17 (1992): 37-47.

23. K. Arceneaux, 2001, op. cit. (see reference 17), p. 145.

24. R. Darcy, S. Welch and J. Clark, Women, Elections and Representation (New York: Longman, 1987).

25. Ohio Legislative Service Commission, A Guidebook for Ohio Legislators, 2007. URL: www.lsc.state.oh.us/guidebook/ (accessed August 15, 2009).

26. L. Braiotta, The Audit Committee Handbook (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

27. Ohio Legislative Service Commission, 2007, op. cit. (see reference 25).

28. A. Bowman and R. Kearney, State and Local Government, 6th ed. (Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin, 2005), p. 160.

29. M.S. Dulaney, A History and Description of the Nebraska Legislative Process (Lincoln, NE: Nebraska Council of School Administrators., 2002)

30. G. Tsebelis and J. Money, Bicameralism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

31. A.W. Richards, “Strategic Planning and Budgeting in the New Texas? Putting Service Efforts and Accomplishments to Work,” International Journal of Public Administration 18 (1995): 409-441.

32. National Conference of State Legislatures, Full- and Part-Time Legislatures. URL:

http://www.ncsl.org/programs/press/2004/backgrounder_fullandpart.htm

35. O. Koppel, “Public Good Provision in Legislatures: The Dynamics of Enlargements,” Economics Letters 83 (2004): 43-47.

36. Council of State Governments, The Book of the States, 2016 (Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments, 2016).

37. As administrative divisions of a state, counties seldom have power to establish their own taxes, but they are often able to adjust tax rates within fixed maximum and minimum parameters.

38. J.F. Zimmerman, Subnational Politics; Readings in State and Local Government (New York: Holt, Rinehart, 1970).

39. H.M. Levin, An Analysis of the Economic Effects of the New York City Sales Tax (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1967).

C.L. Rogers, “Local Option Sales Tax (LOST) Policy on the Urban Fringe,” Regional Analysis and Policy 34 (2004): 27-50.

40. A.D. Sokolow, Town and Township Government: Serving Rural and Suburban Communities (New York: Marcel Dekker, 1996).

41. H.G. Frederickson and G.A. Johnson, “The Adapted American City: A Study of Institutional Dynamics,” Urban Affairs Review 36 (2001): 872-884, p. 872.

42. K.A. Foster, The Political Economy of Special-purpose Government (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1997).

43. S. Scott and J. C. Bollens, “Special Districts in California Local Government,” Western Political Quarterly 3 (1950): 233-243.

44. T. Loftus and H.G. Rennie, Analysis of Enabling Legislation from a Multi jurisdictional Watershed Perspective. URL: www.storm.warrenswcd.com/Documents/FinalReport-OSTF-319-Grant-StormWater-MGT-Watershed-Basis.pdf.(accessed August 15, 2009).

45. D.A. Austin, “A Positive Model of Special District Formation,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 28 (1998): 103-122.

46. J. Lang, New Urban Renewal in Colorado’s Front Range, Issue Paper 2-2007 (Golden, CO: Independence Institute, 2007).

47. H.G. Cisneros, Regionalism: The New Geography of Opportunity (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 1999).

G. Marks and L. Hooghe, Contrasting Visions of Multi-level Governance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

48. K. Mizany and A. Manatt, What’s So Special about Special Districts?: A Citizen’s Guide to Special Districts in California (Sacramento, CA: California State Legislature, 2002). URL: www.csda.net/images/Whatsso.pdf

49. T. Bui and B. Ihrke, It’s Time to Draw the Line: A Citizen’s Guide to LAFCOs (Sacramento, CA: California Senate, 2003).

50. K. Mizany and A. Manatt, 2002, op. cit. (see reference 48).

51. U.S. Census Bureau, 2002 Census of Governments. URL: www.census.gov/govs/www/cog2002.html

52. D.J. Condron and V. J. Roscigno, “Disparities Within: Unequal Spending and Achievement in an Urban School District,” Sociology of Education 76 (2003): 18-36.

53. A. Feuerstein, “Elections, Voting, and Democracy in Local School District Governance,” Educational Policy 16 (2002): 15-36.

54. J.P. Danzberger, “Governing the Nation’s Schools: The Case for Restructuring Local School Boards,” Phi Delta Kappan 75 (1994): 367-373.

55. L. Barrow and C. E. Rouse, “Using Market Valuation to Assess Public School Spending,” Journal of Public Economics 88 (2004): 747-1769.

56. U.S. Census Bureau, 2002, op. cit. (see reference 51).

57. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. “Local Authorities,” URL: www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/english/agenda21chapter28.htm

58. B. Evans, M. Joas, S. Sundback and K. Theobald, Governing Sustainable Cities. (London, UK: Earthscan, 2005).

59. Evans, B., M. Joas, S. Sundback and K. Theobald, “Governing Local Sustainability,” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 49 (2006): 849-867.

60. B. Evans, M. Joas, S. Sundback and K. Theobald, 2005, op. cit. (see reference 58).

61. B. Costantinos, “Sustainable Development and Governance Policy Nexus: Bridging the Ecological and Human Dimensions.” In Gedeon Mudacumura, Desta Mebratu and M. Shamsul Haque, eds., Sustainable Development Policy and Administration (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2006), p. 68.

62. United Nations, 2009, op. cit. (see reference 57).