Chapters

Chapter 8: Courts

8.A – Introduction

When thinking about courts many of us think about the statute of “Blind Justice” – also known as Lady Justice – that adorns the front of many courthouses around the country. Often portrayed blindfolded and holding balance scales and a sword, the figure represented is Themis, the Greek Goddess of Justice and law. The blindfold she wears represents the impartiality with which justice is served, the scales represent the weighing of evidence on either side of a dispute brought to the court, and the sword signifies the power that is held by those making the ultimate decision arrived at after an impartial and fair hearing of evidence. In fact, in ancient Greece judges were considered servants of Themis, and they were referred to as “themistopolois.”

Whether or not state and local court systems in these modern times are providing blind justice as represented by the statute of Themis could be debated. While residents in communities around the country ideally hope their own court system is impartial and immune to outside influences, few who work in or participate in American state court systems believe this is fully true; in fact, there is evidence that suggests that protection from outside influences upon the courts is becoming less and less assured. Judges today are increasingly called upon to make tough public policy decisions, with the outcomes – some of which entail promoting sustainability – often being popular with the parties engaged in a particular policy issue. Very often such decisions affect tradeoffs of economic, social and environmental goals, leaving some parties pleased and others anxious to “redress the balance” either in new statutory language or through further litigation in the courts. This continuation of the dispute through legal action often involves seeking out “more friendly courts” with more sympathetic judges in which to file their actions.

At the beginning of the American republic, the Founding Fathers clearly believed that the judicial branch would be weak — far weaker than either the Executive or the Legislative branches. In this regard, according to Alexander Hamilton (1788) writing in the Federalist Papers (number 78):

The Executive not only dispenses the honors but also holds the sword of the community. The legislature not only commands the purse but also prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever.1

Simply speaking, Hamilton thought the judicial branch, with its lack of command of either physical or financial resources, could never overpower the two other branches of government.

Contemporary state, county, and municipal courts face many challenges, with some of these challenges placing an impact upon the provision of “Blind Justice” which society expects of its courts. Despite the critical role of courts in state and local government, many citizens are unaware of the importance of their state and local court systems. In a July 2005 survey about civic education carried out by the American Bar Association, only 55 percent of the participants were able to name the three branches of government.2 In point of fact, state and local courts have 100 plus times the number of trials and handle five times as many appeals as the federal courts.3

Learning Objectives

This chapter will:

- explore the major aspects of state and local courts.

- discuss how these court systems operate.

- outline selection processes for the judiciary.

- introduce the topic of judicial federalism; including the challenges courts will face in the future.

- discuss the impacts courts have had and will have in the future with respect to the promotion of sustainability.

8.B – State Court Systems

Unlike other countries with a single, centralized judicial system the United States operates under a dual system of judicial power – one system of courts operates within each state’s constitution, and the other system of courts derives from the provisions of Article III of the United States Constitution. Thus, each state, as well as the federal government, are responsible for enforcing the laws, and state and local courts and federal courts adjudicate both civil and criminal case matters. It follows that Americans are dual citizens; not only are they citizens of the United States of America, but they are citizens of the state, which they reside as well.

With the exception of the appellate process, and possibly in the procedural realm of injunctive relief, the national and state courts are virtually separate and distinct entities. For example, since the U.S. Constitution gives the U.S. Congress authority to make uniform laws concerning bankruptcies, state courts largely lack jurisdiction in the matter. On the other hand, the U.S. Constitution does not give the federal government authority over the regulation of family life; in matters of family law (e.g., divorce, child custody, probate, division of property, etc.) a state court would have jurisdiction and a federal court would likely not hear cases.4 While operating largely separately, the two systems can come together in the U.S. appellate courts (including the U.S. Supreme Court). The U.S. Supreme Court has final interpretative authority in the country with respect to disputes regarding the meaning of the U.S. Constitution and interpretation of its provisions by all “inferior” (i.e., subordinate) courts in the country. This situation of the coming together of the state and federal courts is a rather rare occurrence and only happens when there is a substantial federal question of law and all remedies at the state level are fully exhausted. Even then, it is entirely left up to the U.S. Supreme Court to decide if it wishes to hear the case.5

State courts were in place after the American Revolution, but with fresh memories of the Colonial Courts controlled as an extension of English rule Americans generally distrusted these state courts.6 Since most states were predominantly rural in the distribution of their populations, conflicts between people tended to be relatively simple and were typically settled informally without the need of court intervention. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that modern unified state court systems emerged, with many of these “upgrades” in the procedures and practices of minor courts coming in response to the many new legal challenges arising from the industrial revolution. With industrialization, the American society was changing so rapidly in so many areas that state legislatures, most of which met for only brief periods of time, neither had the time nor the resources to develop statutes to cope with the rising problems. For example, with the advent of labor unions, patent rights and royalties associated with new technology, and complaints over growing corporate monopolies such as utilities and the railroads brought many disputes to the courts for resolution in the absence of governing statutes.7 This set of circumstances resulted in many conflicts entering into state courts through parties asking the courts to use their common law “equity” powers to resolve contentious commercial, real estate, industrial insurance, and similar disputes born of a rapidly industrializing nation.

While general jurisdiction county courts were well established in American society and enjoyed growing legitimacy as the memories of colonial rule faded over time, these courts were neither adequately staffed nor properly organized to address the increasingly complicated problems of the day. When state and local courts became overwhelmed with litigation and lost faith in the legislative process to bring timely relief, the State Bar Associations (the professional licensing association of lawyers in a state) began to orchestrate reform in state court systems. This reformation depended on the separation of powers argument that empowered state supreme courts to create “unified” courts by mandate of the court as opposed to legislative action. More specifically, state supreme courts acted on their own authority as a separate branch of government, establishing a system of courts wherein the state supreme court sits atop a system of interconnected courts, all of which adhere to the same rules and procedures on how cases (criminal, civil and equity) are processed and appeals are made. In due course, state legislatures codified the key elements of unified court operations into state statutory law. In virtually all of the states, this creation of unified court systems resulted in the addition of new jurisdictions, the development of uniform procedures, the common training of court personnel, and in many cases, the development of specialized courts such as small claims courts, juvenile courts, and family law courts.

Through the U.S. Constitution (Article 111, Sec. 1) the U.S. Congress has the power to establish “inferior courts” for hearing cases arising from federal law. As previously noted, the interaction between the federal and state courts is relatively rare, with the most notable exception being in the area of Civil Rights. Federal statutes such as the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act can, and have, brought federal and state court systems into close contact. As a general rule, state courts cannot interpret state constitutions in a way that undermines a U.S. Supreme Court ruling by condoning a less protective standard with respect to a civil right recognized to exist in the U.S. Constitution. On the other hand, state courts are permitted to interpret their state constitutions to require greater protections than those required by the federal courts.

Though federal and state court systems happily coexist in most respects, such mutual coexistence is not uniformly the case. For example, during the 1960s there was so much conflict between federal and state courts that a U.S. constitutional revision was proposed calling for the creation of the “Court of the Union,” a judicial tribunal which would have addressed the alleged encroachments upon state judicial power by the federal system.8 Even though the “Court of the Union” idea ultimately failed to gain traction with either the public or the legal community, the conflict between the two systems that gave rise to the idea has not fully abated. An example of this conflict is the deep disagreement over capital punishment arising in late 2007.

While waiting for a U.S. Supreme Court decision as to whether the current method of lethal injection represents “cruel and unusual punishment,” a violation of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, many of the 36 states using lethal injection as a method of execution placed a de facto moratorium on executions. Other states boldly rebuked the U.S. Supreme Court and moved ahead with planned executions, despite the Supreme Court’s plea to await the outcome of its hearing of a key case. On November 2, 2007, barely a month after the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case [granted certiori] on lethal injection, the Florida Supreme Court unanimously ruled that their state’s new method for carrying out lethal injections, after changes in the procedure were made which were prompted by a botched execution in December, do not violate the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

8.C – How State Courts Work

Comparing one state court to another is like comparing apples to oranges in some respects. Some state court systems are extremely complex, while others are rather simple in their structure. For example, the state of New York, with a population of 19 million residents in the year 2000, are served by approximately 3,500 full-time judges working within 13 different layers of courts. In contrast, California, with almost double the population of New York, has only three layers of courts and employs only 1,600 judges. Even though both California and New York, and their respective local court systems, operate under the same general principles and under the structure of a unified court system, they do not operate in the same way. In order for attorneys to practice law in state courts, they must be able to demonstrate knowledge of that particular state’s legal system by either passing the state bar examination or otherwise demonstrating sufficient command of the particular state’s system of courts. The caseloads for state courts vary widely, and these workloads seem to have little to do with the size of the state’s population. Generally speaking, western states’ courts, which were formed later in the nation’s history, tend to be more modern and simplified when compared to those of longstanding operation in the eastern states.

The organization of state and local courts tends to reflect two major influences: 1) the organizational model set by the federal courts; and 2) each state’s judicial preferences as manifested in state constitutions and judiciary statutes.9 The increased influence of states’ constitutions within their judicial system, particularly in regards to civil rights, is known as judicial federalism. As the chapter on State Constitutions noted, Judicial Federalism is at play when state courts address the state’s constitutional claims first, and only consider federal constitutional claims when extant cases can not be resolved solely upon state grounds.

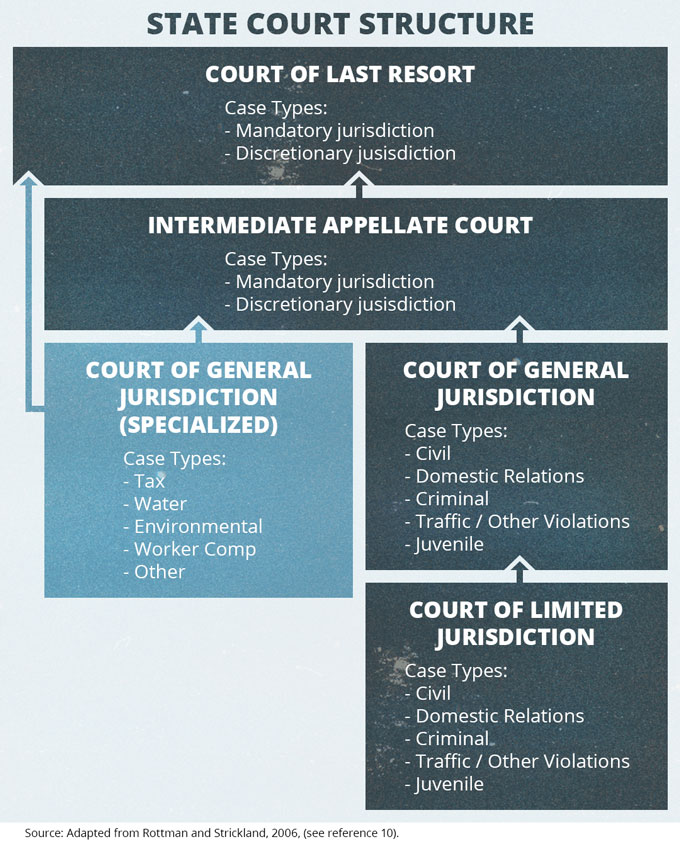

The legal terminology and structure of each state’s court are quite diverse, but they all follow a generic three-tiered structure. At the base is a system of general and limited jurisdiction trial courts of original jurisdiction, with an intermediate set of appellate courts in the middle, and, at the top, the Court of Last Resort (also an appellate court). In addition, many states are increasingly using specialized, sometimes known as problem-solving, courts as needed. The fundamental distinction between trial courts and appellate courts is that trial courts are those of the first instance that decide a dispute by examining the facts. Appellate courts review the trial court’s application of the law with respect to the facts as recorded in the official proceedings of the case in question.10 Figure 8.1 reflects how a generic three-tiered court system with a specialized court may operate. Some states’ court structure, usually those with small populations, may be more simplified than the generic system, while in some cases the states’ structure is more complex than the diagram implies.

8.C.I – Trial Courts:

Trial courts often don’t garner the attention of either states’ higher courts or the federal courts, but they represent the veritable workhorses of the court system. Typically, each state has two types of trial courts of original jurisdiction, one of limited jurisdiction and one of general jurisdiction. Funding for trial courts of general jurisdiction generally comes from a combination of state and local sources. In most states, courts of limited jurisdiction are principally funded by local governments.

Trial courts of limited jurisdiction, as the name suggests, deal with specific types of cases and are often presided over by a single judge operating without a jury. Found in all but six states, courts of this type typically hold preliminary hearings in felony cases and exercise exclusive jurisdiction over misdemeanor and ordinance violation cases.11 Geographically, the jurisdiction of these courts varies across the states, but by-and-large they possess either a countywide jurisdiction or serve a specific local government such as a city or town. If there were an entity we could call a “community court,” it would be these courts. They are located within or near a community and handle cases arising from misdemeanor offenses and ordinance violations. The courts of this type include, but are not limited to the following:

- Probate Court: Handles matters concerning administering the estate of a person who has died.

- Family Court: Handles matters concerning adoption, annulments, divorce, alimony, custody, child support, and other family matters.

- Traffic Court: Regarding cases involving minor traffic violations.

- Juvenile Court: Handles cases involving delinquent children under a certain age.

- Municipal Court: This court handles cases involving offenses against city ordinances.

General jurisdiction trial courts are the main trial courts in the state system, and in most cases, the highest trial court. These courts are generally divided into circuits or districts. In some cases, the county serves as the judicial district, but in most states, a judicial district embraces a number of counties, which is why they are often referred to as county courts. General jurisdiction trial courts hear cases outside the jurisdiction of the limited jurisdiction trial courts, such as felony criminal cases and high stakes civil suits. In most states cases are heard in front of a single judge, often with a jury.

8.C.II – Intermediate Appellate Court:

Intermediate Appellate Courts go by many names, including Superior Court, Appellate Division, Court of Appeals, and even Supreme Court. With the exception of 11 states, which usually have small populations, states have some form of intermediate appellate courts. The main role of these courts is to hear appeals from trial courts. Any party, except in a case where a defendant in a criminal trial has been found not guilty, who is not satisfied with the outcome from the trial court may appeal to an intermediate appellate court. States’ intermediate appellate courts are structured in a variety of ways, but typically they are regionally based and divided into “divisions,” “courts” or “districts.” For example, Florida has five District Courts of Appeal while more sparsely populated Idaho has a single Court of Appeals. The courts are usually set up with the judges working in panels of three or more (always an odd number), and the majority of judges decides the outcome of the cases brought to the court. The appellate courts do not have juries, do not hear from witnesses or review the facts of the case, but instead read briefs and hear arguments from the parties’ attorneys to decide issues of law or process raised in the cases brought up on appeal. The majority of the time its decisions are final, but it is possible to appeal to the next appellate court level, often the Court of Last Resort.

8.C.III – Court of Last Resort:

All states have a Court of Last Resort, primarily referred to as the Supreme Court, which acts as the state’s highest appellate court. In fact, two American states — Oklahoma and Texas — have two Courts of Last Resort; one represents a conventional Supreme Court and the second constitutes a Criminal Court of Appeals. The most common arrangement, found in 28 states, is a seven-judge court; 16 states have five Supreme Court justices, while five states have nine judges.12

With the exception of the 11 states that don’t have an intermediate court of appeals, the Courts of Last Resort have discretion as to whether or not they will hear a case. As an appellate court, it hears cases without a jury, focusing on major questions of law and constitutional issues. Many Courts of Last Resort do have original jurisdiction in certain specific matters, such as the reapportioning of legislative districts. The decisions coming from these courts are final, with the extremely rare exception of when the U.S. Supreme Court decides to hear an appeal from a state.

There are two ways a case regarding a state can be heard in the U.S. Supreme Court. The first, and almost nonexistent, is with the U.S. Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction, which involves cases between the United States and a state, between two or more states, and between a state and a foreign country. These cases typically go through the federal system, therefore rarely involve a decision from a state court. The second path for a state-based case is through the U.S. Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction. In these instances, the U.S. Supreme Court can choose to hear a case appealed from a state’s Court of Last Resort. In order for this to occur, there must be a substantial federal question involved and the case must be viewed as “ripe,” meaning the petitioner has exhausted all potential remedies in the state court system and the resolution of the case can set a useful precedent for the future resolution of similar cases.

The Fifth Amendment case of Dolan v. City of Tigard serves as a good example of such a case. This case centered on zoning regulations and property rights. Dolan, an owner of a plumbing supplies store, appealed her claim though the Oregon court system where the Oregon Supreme Court found for the City and rejected the argument that an unconstitutional taking of private property by the government without just compensation occurred as a result of a zoning decision made by the city. As the case involved Fifth Amendment constitutional rights, the federal courts determined that this case raised a question of federal law. Given that essential determination, Dolan was able to appeal her case to the federal courts, and ultimately all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The U.S. Supreme Court found in favor of Dolan, causing local governments across the country to take notice of new requirements for determining just compensation in similar cases.

8.C.IV – Problem-Solving Courts:

Problem-solving courts commonly referred to as “specialized courts” dispensing “therapeutic jurisprudence,” have emerged in most American states over the past decade. Problem-solving courts relieve overwhelmed legal systems dealing with persons and families whose actions stem from problems better dealt with by “supervised treatment” rather than incarceration or similar forms of punitive governmental sanctions. These courts represent an attempt to craft new, adaptive responses to chronic social, human and legal problems that are resistant to conventional solutions associated with the adversarial process.13

Though lacking a precise definition or legal philosophy, problem-solving courts share a basic theme: a desire to improve the results that courts achieve for victims, litigants, defendants, and communities through a collaborative process rather than the conventional adversarial process.14 Traditional courts tend to focus on the finding of guilt or innocence, entail looking backward in time, and are conducted in an adversarial way. In comparison, specialized courts focus on the identification of therapeutic interventions, seek to affect future outcomes, make use of a collaborative process, and involve a wide range of court-based and community-based services and stakeholders.15

There are a number of factors that have led to the rise of special courts, including prison (state facilities) and jail (county and city facilities) overcrowding, highly stressed social and community institutions, and increased awareness of social issues such as domestic violence. While increased social awareness has indeed played some role in the development of these specialized courts, the lack of resources available to state and local court systems has been the major driver behind the broadening use of such courts; the caseloads of the courts have increased substantially in recent decades while the resources available to the courts have not increased proportionately. For example, from 1984 to 1997 the number of domestic violence cases in state courts increased by 77 percent.16 Commenting on rising caseloads, Minnesota Chief Justice Kathleen Blaze stated, “You just move ‘em, move ‘em, move ‘em. One of my colleagues on the bench said, ‘you know, I feel like I work for McJustice: We sure aren’t good for you, but we are fast.”17

Problem-solving courts got their start in 1989 when Dade County, Florida experimented with a drug court. The drug court, in an attempt to address the problem of criminal recidivism (re-offense) among illegal drug use offenders, sentenced such repeat offenders to a long-term, judicially supervised drug treatment instead of incarceration. In reflection of Dade County’s success with this alternative to incarceration, drug courts taking a similar approach to drug use offenders began to crop up all over the United States. As of April 2007, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that there were 1,699 fully operational drug courts in the United States, and another 62 tribal drug courts.18

Since this development in 1989, a variety of specialized courts have emerged, primarily designed to tackle difficult social issues. For example, New York City opened its Midtown Community Court in 1993 to target misdemeanor “quality-of-life” crimes, such as prostitution and shoplifting. Instead of relying upon traditional sentencing involving incarceration, offenders were required to pay back the community for the harm they caused by community service work such as cleaning local parks, sweeping streets and painting over graffiti. In addition, to address the underlying cause of the problem behavior, the offenders were mandated to receive “therapeutic” social services, such as counseling, anger management instruction, substance abuse treatment, and job training.19 Typically, elements of the local community are also engaged in the work of the problem-solving courts by participating on advisory panels, providing volunteer services, and taking part in town hall meetings. The City of Portland, Oregon, for example, opened a number of “Community Courts” throughout the city, in many cases holding court at existing local community centers.

Evidence collected in evaluation studies conducted on many drug courts indicates that these problem-solving courts tend to achieve favorable results with regards to keeping offenders in treatment, reducing their drug use, reducing recidivism, and economizing on jail and prison costs. The rate of retention in drug abuse treatment ordered by drug courts is typically 60 percent, as compared to only 10 to 30 percent for voluntary programs. Moreover, drug court participants have far lower re-arrest rates than do persons taken into the traditional court process.20 Even after fully accounting for administrative and overhead costs, in a two-year period, the drug court in Multnomah County(Oregon) saved $2.5 million in criminal justice system costs, with an additional savings being made in outside the court system costs such as reduced theft and reduced public assistance payments. Those associated costs were estimated at $10 million.21

The types of problem-solving courts are many, but the majority of them fall into the categories of limited or general jurisdiction trial courts (courts of original jurisdiction). The most common specialized courts are those that work on social issues, primarily substance abuse and family courts. Some examples of specialized courts include: gun courts, gambling courts, homeless indigent courts, mental-health courts, teen courts, domestic violence courts, elder courts, and community courts involving lay citizens in the process of arranging for property crime offenders to engage in compensatory justice with respect to those whom they victimized.

Some states have taken it upon themselves to permit the establishment of specialized courts for the protection of the environment and for addressing the economic costs and benefits of pursuing sustainability. Such specialized courts have been created to deal with highly complex issues, which require extraordinary scientific and technical knowledge on the part of the court. For example, the State of Montana created a Water Court to expedite and facilitate the statewide adjudication of state water right claims; once the adjudication process is complete the state may dissolve the court.22

In addition to the difficult adjudication of rival water rights claims, Colorado’s version of the Water Court has jurisdiction over the use and administration of water and all water matters within its statewide jurisdiction.23 Vermont has established an Environmental Court to hear matters on municipal and regional planning and development, to hear disputes over state solid waste ordinances, and to handle cases arising from the enforcement actions of the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources. As matters relating to global climate change and the more rigorous regulation of greenhouse gases arise, it is likely that more specialized courts will be created in other states to deal with the disputes arising from the active pursuit of sustainability in our states and local governments.

States are also developing specialized courts to manage economic disputes that arise in the course of commercial activity (such as business formation, business transactions, and the sale/purchase of business assets). Five states have Tax Courts that deal exclusively with tax disputes. Montana, Nebraska, and Rhode Island developed specialized courts to deal exclusively with Workers’ Compensation cases. In many states, which do not have such specialized courts there has been a steady trend in the growth of the number and range of activities of administrative law judges. These “hearings officers” work within administrative agencies, which engage in regulatory actions that give rise to many disputes (environmental regulations, labor/management actions under collective bargaining agreements, compensation for damages incurred from state government action on one’s property, etc.). These administrative law judges (ALJs) hold quasi-judicial hearings, carefully weigh the arguments of the agency and aggrieved citizens, and have the authority to mediate, arbitrate and ultimately decide upon an outcome to a case, which is binding on all parties. While such decisions made by ALJs can be appealed to the courts, state court judges seldom overturn their rulings.

8.D – Judicial Selection

The manifest aim of the judicial selection process in the American states is to select a judiciary that is as impartial as the Greek Goddess Themis, but one that is at the same time accountable to the will of the people of the state. Unlike the federal judiciary where lifetime appointments are made to the federal district, circuit and supreme courts, in the states nearly all judges serve for fixed terms of office and most are subject to some method of retention in office-based upon a vote of the people. Each state uses a system of selecting judges they feel is best suited to accomplish the dual goals of impartiality and accountability to the people. In most cases, a state’s judicial selection process does not catch the public’s attention given the limited knowledge citizens typically command regarding the courts and the actions of their judges; some particularly cynical observers have characterized judicial selection processes as being “about as exciting as a game of checkers…played by the mail.”24

There is no simple way to describe states with respect to their form of judicial selection system, because judges in different (or even the same levels of courts) within one state may be selected through different methods.25 A system to select a judge for the intermediate appellate court, for example, may be different than the system used for the Court of Last Resort, and different again from the system used for recruitment to the trial courts. Making things even more complex, the selection process for subsequent terms may be different than the initial term of office.

No single selection process – such as gubernatorial appointment, merit commission screening for gubernatorial appointment, non-partisan election, partisan election, legislative appointment, nomination to vacancies by county commissioners – currently dominates over other processes, nor do these selection processes within each state remain static over time. For example, in 1980 it was the case that 45 percent of the states used partisan elections and 29 percent of the states used non-partisan elections as their respective methods for selecting judges to trial courts; by 2004, however, those figures were just about reversed; in 2004, 44 percent of the states were using non-partisan elections and 35 percent were using partisan elections for selecting their trial court judges.26

While there are many types of selection processes, four principal processes are used in the U.S. for judicial selection within the states: partisan election, non-partisan election, appointment, and the Merit System (known as the Missouri Plan). No one process dominates the others in extent of use, or in the level of controversy associated with its use. There are some regional differences in evidence in where each type of judicial selection process tends to be concentrated. For example, some of the nation’s most conservative states, including Texas and states in the “Deep South,” use partisan elections principally, while many Midwest states tend to make use of the gubernatorial appointment process. Table 8.1 shows how each state selects its judiciary as of the present time

| Court of Last Resort Name/s | Method of Selection | Intermediate Appellate Court/s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Criminal Appeals / Court of Civil Appeals |

| Alaska*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Arizona*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Arkansas | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| California | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeal |

| Colorado*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Connecticut | Supreme Court | Appointment | Appellate Court |

| Delaware | Supreme Court | Appointment | – |

| Florida | Supreme Court | Appointment | District Courts of Appeals |

| Georgia | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Hawaii | Supreme Court | Appointment | Intermediate Court of Appeals |

| Idaho | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Illinois | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Appellate Court |

| Indiana*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals/Tax Court |

| Iowa*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Kansas*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Kentucky | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Louisiana | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Appeal |

| Maine | Supreme Judicial Court | Appointment | – |

| Maryland | Court of Appeals | Appointment | Court of Special Appeals |

| Massachusetts | Supreme Judicial Court | Appointment | Appeals Court |

| Michigan | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Minnesota | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Mississippi | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Missouri*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Montana | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | – |

| Nebraska*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Nevada | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | – |

| New Hampshire | Supreme Court | Appointment | – |

| New Jersey | Supreme Court | Appointment | Appellate Division of Superior Court |

| New Mexico | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| New York | Supreme Court | Appointment | Appellate Division of Supreme Court/Appellate Terms of Supreme Court |

| North Carolina | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | – |

| North Dakota | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | – |

| Ohio | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Courts of Appeals |

| Oklahoma*** | Supreme Court/Criminal Court of Appeals | Appointment/Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Oregon | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Pennsylvania | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Superior Court/Commonwealth Court |

| Rhode Island | Supreme Court | Appointment | – |

| South Carolina | Supreme Court | Appointment # | Court of Appeals |

| South Dakota | Supreme Court | Appointment | – |

| Tennessee | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals/Court of Criminal Appeals |

| Texas | Supreme Court/Criminal Court of Appeals | Partisan Election/Partisan Election | Court of Appeal |

| Utah*** | Supreme Court | Appointment | Court of Appeals |

| Vermont | Supreme Court | Appointment | – |

| Virginia | Supreme Court | – | Court of Appeals |

| Washington | Supreme Court | Appointment # | Court of Appeals |

| West Virginia | Supreme Court of Appeals | Nonpartisan Election | – |

| Wisconsin | Supreme Court | Partisan Election | Court of Appeals |

| Wyoming*** | Supreme Court | Nonpartisan Election | – |

| Appellate Court Justices | General Trial Court/s | Method of Selection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Partisan Election / Partisan Election | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Alaska*** | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Arizona*** | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Arkansas | Nonpartisan Election | Chancery/Probate Court/Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| California | Appointment | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Colorado*** | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Connecticut | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Delaware | – | Superior Court/Court of Chancery | Appointment/Appointment |

| Florida | Appointment | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Georgia | Nonpartisan Election | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Hawaii | Appointment | Circuit Court | Appointment |

| Idaho | Nonpartisan Election | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Illinois | Partisan Election* | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Indiana*** | Appointment/Appointment/Appointment | Superior Court/Probate Court/Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Iowa*** | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Kansas*** | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Kentucky | Nonpartisan Election* | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Louisiana | Partisan Election* | District Court | Partisan Election |

| Maine | – | Superior Court | Appointment |

| Maryland | Appointment # | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Massachusetts | Appointment | Supreme Court | Appointment |

| Michigan | Nonpartisan Election | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Minnesota | Nonpartisan Election | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Mississippi | Nonpartisan Election* | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Missouri*** | Appointment | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Montana | – | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Nebraska*** | Appointment** | District Court | Appointment |

| Nevada | – | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| New Hampshire | – | Superior Court | Appointment |

| New Jersey | Appointment | Superior Court | Appointment |

| New Mexico | Partisan Election | District Court | Partisan Election |

| New York | Appointment/Appointment | Supreme Court/County Court | Partisan Election/Partisan Election |

| North Carolina | – | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| North Dakota | – | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Ohio | Partisan Election | Court of Common Pleas | Partisan Election |

| Oklahoma*** | Appointment* | District Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Oregon | Nonpartisan Election | Circuit Court/Tax Court | Nonpartisan Election/Nonpartisan Election |

| Pennsylvania | Partisan Election/Partisan Election | Court of Common Pleas | Partisan Election |

| Rhode Island | – | Superior Court | Appointment |

| South Carolina | Appointment # | Circuit Court | Appointment |

| South Dakota | – | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Tennessee | Partisan Election/Partisan Election | Circuit, Criminal, Chancery, & Probate Court | Appointment |

| Texas | Partisan Election | District Court | Partisan Election |

| Utah*** | Appointment | District Court | Appointment |

| Vermont | – | Superior Court/District Court | Appointment/Appointment |

| Virginia | Appointment # | Circuit Court | Appointment |

| Washington | Nonpartisan Election | Superior Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| West Virginia | – | Circuit Court | Partisan Election |

| Wisconsin | Nonpartisan Election | Circuit Court | Nonpartisan Election |

| Wyoming*** | – | District Court | Appointmen |

Table 8.1 Judicial Selection Method by State (*=Justices chosen by district; **=Chief Justice chosen statewide, associate judges chosen by district; ***=Uses of the Merit System for Judicial Selection; #=Legislative Appointment)

8.D.I – Partisan and Non-Partisan Elections:

As of 2006, 39 states elect some or all of their judges; this represents nearly 90 percent of state judiciaries across the country. From this statistic alone it is clear that the goals of impartiality and public accountability are both important elements of state and local government judicial selection in the U.S. Alexander Hamilton (1788) spoke for the Founding Fathers in Federalist Paper No. 78 wherein he argued that if judges in federal courts were chosen by elected officials they would harbor “too great a disposition to consult popularity to justify a reliance that nothing would be consulted but the Constitution and the laws.”27 In 1939, well over a century after Hamilton’s warning, President William Howard Taft described judicial elections in the U.S. as “disgraceful, and so shocking…that they ought to be condemned.”28

Alexander Hamilton and former-President Taft may well be turning in their respective graves as the results of one national survey conducted in 2000 found that 78 percent of Americans believe their state and local judges are influenced (that is, their impartiality is compromised) by having to raise campaign funds.29 Even so, voter turnout for judicial elections is habitually low as many voters skip past these elections. At times the biases in the operation of courts associated with popular elections can be severe. For example, 1990 the U.S. Justice Department used federal anti-discrimination statutes to invalidate the State of Georgia’s system of electing judges because it was found to be discriminatory against African Americans.30

Citizens are poorly informed about judges because, in most states, there are state supreme court-issued limits or guidelines, derived from the American Bar Association’s judicial canons, as to what a judicial candidate can say or do while campaigning for judicial office. These limitations tend to be especially strict in states with non-partisan elections. For example, the Minnesota Code of Judicial Conduct Canon 5(A)(3)(d)(i) prohibits judicial candidates from announcing their views on disputed legal or political issues.31 Yet there are a handful of states, such as Texas, where the judicial elections are highly partisan, extremely expensive, and vehemently contested.

According to Henry Glick and Kenneth Vines, in a great many cases judicial seats that are nominally up for election are vacated by sitting judges shortly prior to the end of their terms of office and filled by judges that are appointed by the sitting governor.32 The governor’s appointee then runs as an incumbent judge during the next election. The impact of such interim appointments has greatly shaped the composition of the nation’s state and local judiciary: between 1964-2004, more than half (52 percent) of the judges serving in partisan election states gained their position through an interim appointment, with the state-specific percentages ranging from 18 to 92 percent.33 These interim appointments more often than not become permanent due to the extremely high retention rate judicial incumbents enjoy in their elections once they get to the bench.

Partisan elections are those in which judicial candidates, including incumbents, run in party primaries and are listed on the ballot as a candidate of a political party.34 In contrast, non-partisan elections are those in which the judicial candidates run on a ballot without a political party designation. There are a few cases where candidates are chosen in a party primary and backed by the party, but they appear without the label on the ballot. The party affiliations of judges aren’t exactly the best-kept secrets; judicial candidates often list a party affiliation in their official biographies, and political parties will often endorse particular judicial candidates.35

In comparing the two elective systems, each one has its own pros and cons. The proponents of partisan election tend to feel strongly that the party affiliation next to a judicial candidate’s name provides important information to voters with respect to the candidate’s likely political philosophy. The proponents counter that “justice is not partisan” – that is, there is no Democratic or Republican form of justice, only the impartial justice dispensed by the blindfolded Themis who is unaware of whether the parties coming before her are Democrats or Republicans. The proponents of partisan election counter that in the non-partisan judicial elections it is the voters who are blindfolded and unable to exercise popular accountability over judges as intended in the election process.

One additional drawback associated with partisan judicial elections is that they can lead to an imbalance among a state’s judiciary in cases where a state features strong one-party dominance. The State of Texas encountered this problem during the indictment of former House Majority Leader Tom Delay for corruption charges. Since Texas judges are elected on a partisan ticket, and often contribute openly to partisan causes, quite a scramble was necessary to identify an impartial trial judge who was acceptable to both the prosecution and defense in the Delay case.36

8.D.II – Judicial Appointments and the Merit System:

There are two common methods of judicial appointment, “simple” gubernatorial appointment and the “Merit System” of appointment. The simple gubernatorial appointment is much like that for federal judges, where the highest elected official (the President in the federal government and the Governor in the states) fill vacancies on the bench. How judges are selected by state governors depends on the governor in question and traditions in the state. Generally speaking, the background of the judge (former prosecutors, defense attorneys, type of pro bono work done, level of activity in local bar associations, etc.), the political needs of the governor (someone from a particular area of the state is needed to balance out an appellate bench), presence or absence of advocacy for particular persons by interest groups (women attorneys, minority attorneys, etc.), the views of leaders of the State Bar Association, and the preferences of the political parties are all more or less in play when state governors make their judicial appointments.37

The Merit System or Missouri Plan system for judicial appointment was designed to “take politics out of judicial selection” by combining the methods of appointment with election in a very particular way. Featuring three distinct components, it is the most complex of the judicial selection processes. Fourteen states use some version of the Missouri plan, with some additional states using a modified version of this type of selection process. Under the provision of the Missouri Plan, candidates for judicial vacancies are first reviewed by an independent, bipartisan commission of both lawyers and prominent lay citizens. From a list of nominees submitted to the commission, three names are provided to the governor from which one person is selected to fill the vacancy on the bench in question. If the governor doesn’t pick one of the three persons put forward by the commission within sixty days, the commission is empowered to make the selection.

Once the judge selected by this process has been in office for one year or more, they must stand in a “retention election” during the next scheduled general election period. In such an election there is no opponent – voters are either voting to retain the judge in office or remove him or her from the judicial post in question. If there is a majority vote to remove the judge from office, the judge must step down and the process starts anew (Missouri Judicial Branch). By making the appointed judge stand for a retention election, the people over whom the judge exercises judicial authority have the ability to remove a judge they feel does not perform his or her duties well. Whether or not this was intentional on the plan of Missouri Plan designers, judicial removal is exceedingly rare; in the first 179 elections held under the Missouri Plan only one judge did not retain his position, and this was a case in which extraordinary circumstances were present.38

The term “merit” in the Missouri Plan judicial selection process implies that nominating commissions are disengaged from party politics, but the extent to which this disengagement is achieved depends in large measure on who selects the commissioners and how they carry out their duties. These two factors vary considerably across the states using the Missouri Plan. In a number of states, the governor has a major role in picking members of the commission, and in other states, interest groups play a significant role, thereby to some extent circumventing of the “de-politicization” goal of the merit selection system.

The geographic basis for the selection of trial court and appellate judges is somewhat different for each state, and for each type of court within the state’s unified court system. For trial courts, a useful general rule of thumb is that judges are elected from within the jurisdiction over which they preside. For example, Montana’s Municipal courts are elected in a nonpartisan election within the city wherein the court operates, while the Water Court, which exercises statewide jurisdiction, is elected in a nonpartisan election from throughout the state. In the majority of states, thirty in all, levels of the state’s appellate courts are either elected or appointed statewide, while six states select all of their appellate justices by district or region.

When it comes to discussions concerning how judges should be selected, the most contentious debates occur on the question of how judges on the Courts of Last Resort should be selected. Even though they are appellate courts, and often use the same process for selecting the immediate appellate court judiciary, there are nonetheless noteworthy differences. The geographic basis for selecting a judge is usually statewide, although in eight states the Courts of Last Resort select judges via districts. This difference between district and statewide selection can be a source of considerable contention within states, particularly in those states with liberal urban centers and conservative rural areas. Terms of office for a judge on the Court of Last Resort ranges from a low of five years to a high of 14 years. There are three exceptions to the fixed-term system of judicial appointment; Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island all appoint their justices until they reach the age of 70 or die in office. Judicial terms offices are eight years or less in 29 states, and more than eight years in 18 states.39 Naturally, the shorter the term of service, the more often a justice has to run in a retention election and must rely upon supporters to organize and finance their campaign. Whenever anyone runs for public office, whether they are a governor, a legislator, or a judge, they’ll need to raise campaign funds and ask citizens and interest groups for their endorsements and “get out the vote” efforts for their candidacy. This type of “politics” carried out by judicial candidates and their challengers, raises the questions of “from whom and how much money was raised,” and how much influence will that citizen or group have when the judge decides cases brought to his or her court?

An overarching question on judicial selection is this — does the method of selection really matter or affect the way courts operate? Evidence suggests that different selection processes produce different results in terms both of who tends to make it to the bench and in terms of rulings made. For example, Nicholas Lovrich and Charles Sheldon found that judicial selection systems that require judicial candidates to campaign actively in competitive elections result in judicial electorates (voters who participate in elections for judges) who are better informed than judicial selection systems which feature only retention elections.40 Similarly, it has been reported that appointed judges are likely to respond to a wider variety of groups and interests, and support individual rights more strongly in their rulings than elected judges.41

8.E – Current and Future Challenges Facing State and Local Courts

State court systems are facing many challenges, both with respect to their workload and their resource limitations. The civil and criminal caseloads of state and local courts are rising appreciatively, but their resources are not growing to match demands being placed upon a “stressed” system of justice in America. The threat to physical safety in the courts and its judiciary is a serious one in many places and a quite justifiable concern in some urban areas in particular. Rural courts, with their broad geographic reaches, face challenges not contemplated in America’s urban centers. The rapidly rising costs of judicial elections in many states reflect an attempt to politicize the courts on the part of some interests, and in the minds of some observers, this movement toward high-cost judicial elections represents a threat to our independent judiciary. In the state of North Carolina the state legislature grew so concerned about this particular danger that they enacted a law setting up a system of publicly financed judicial elections as an experiment.

The demand upon state court systems is rising in all sectors, and at a more rapid rate than the increase of the general population. Between 1993-2002 trial courts across the country saw a 12 percent increase in civil case filings, an increase in criminal case filings by 19 percent, an increase in domestic relations case filings by 14 percent, an increase in juvenile case filings of 16 percent, and an increase in traffic cases by 2 percent.42 Though traffic cases account for about 60 percent of all cases filed in trial courts, the increase in the number of complicated and time-intensive cases such as civil, criminal and domestic relations case filings place a far greater strain on the courts than the more routine traffic cases. The number of judges and courtrooms in operation has not kept pace with the growth in caseloads; in the period 1993 to 2002, state court system judiciaries increased by only 5 percent.43

Court-related violence and courtroom safety is a chronic, costly preoccupation for those professionals working inside the criminal justice system, but it is not one that gets much public attention.44 Although this is an ongoing issue throughout the country, a number of high profile incidents occurred in 2005 which served to highlight the serious threats state and local courts must plan for on a regular basis. In February of 2005, a Federal judge arrived at her Chicago residence to find her husband and mother murdered by Bart Ross, a 57-year-old electrician whose medical malpractice claim was dismissed in a court hearing. A mere two weeks later in Atlanta, Georgia four people, including a state judge and court reporter, were murdered when a defendant on trial for rape overpowered the sheriff’s deputy escorting him to the courtroom and took the deputy’s gun. In a less violent, but more commonly occurring case of threatening behavior toward judges, the Florida state court trial judge who ordered the feeding tube removed from Terri Schiavo, who was severely brain-damaged, was harassed and received death threats from people who disagreed with his ruling.

In reaction to such events, a study on courtroom safety provisions present in California courts found that two-thirds of the state’s courthouses lacked adequate security, and a companion survey found that 40 percent of California’s state and local prosecutors felt threatened in their jobs. Areas with the poorest security provisions were rural and local courts, which usually rely on local funding for their operations. As an appellate court judge noted, “In a society as litigious as ours, the courtroom has become the theater for emotional catharsis.”45

Heavy caseloads, the lack of resources and inadequate courtroom security are real concerns for professionals working in the criminal justice system, but it is the increased politicization of the courts and judiciary that is considered the greatest long-term threat to the state and local court systems. This term applies to attempts made to provide one political party or major interest group an unfair advantage to promote their interests at the likely expense of the public interest. While all Americans have an interest in the existence of impartial, efficient and legally competent court services, narrow interests sometimes seek to “plant” judges on the bench to gain an advantage in cases involving the adjudication of their affairs. The independence and impartiality of the judiciary, as well as the effective operation of the checks and balances between the three branches of government, are compromised when excessive politicization occurs. The two means used most frequently to politicize the courts are “Court Stripping” and judicial selection.

According to the editors of the Oxford American Dictionary, “Court stripping is when legislatures try to remove power from the courts, usually federal but often state, so that the courts can’t rule on laws they passed.”46 The most blatant instance of this method of politicization of the judiciary occurred in 2005 when the Republican majority in the United States Congress attempted to strip Florida state courts of their jurisdiction over a state matter – in this case, the regulation of medical practice – by imposing federal jurisdiction and ordering the federal courts to consider the claims of Teri Schiavo’s parents. The Florida Court ordered that Teri Schiavo’s feeding tube be removed, an action which would ultimately end her life; her parents wanted the tube to remain in hopes she would one day recover from her injuries. Ultimately, the Florida state court decision stood as a consequence of the reaffirmation of state authority to regulate medical practice within their jurisdictions. There are, and will continue to be, further attempts at court stripping. Upset with some court rulings, some Arizona legislators tried, without success, to enact legislation that would have shifted the power to write court rules from the Arizona Supreme Court, their court of last resort, to the legislature. Court stripping can sometimes happen after a court ruling; for example, although clearly an unconstitutional action in violation of the separation of powers, the Delaware Legislature recently enacted legislation overturning its Supreme Court’s interpretation of “life imprisonment with the possibility of parole.”47

Often veiled as “judicial reform,” political parties and interest groups in some states are trying to alter the process of how judges are selected and retained in order to change the political makeup of the judiciary. Usually, the techniques used appear to be politically neutral “improvements,” such as changing the geographic location of selection, the process of selection, and the term lengths. However, underlying the proposed changes are plans for “stacking the deck” with judges more friendly to their interests. For example, in 2006 Oregon Ballot Measure 40 was introduced to amend the Oregon State Constitution to require judges for the Supreme Court and the Appellate Court to be elected by district rather than statewide. The candidate would have to be a resident of the newly formed district for at least a year before the election.48 The ballot measure failed with 56 percent of the voters opposing. Had the measure passed and been enacted, the political makeup of the Oregon courts could have been altered as the state’s sparsely populated rural areas are typically conservative and the heavily populated urban centers are generally liberal. This type of politicization of courts is nothing new, of course. In 1997 the Illinois General Assembly changed the state’s Supreme Court districts to make it more difficult for Democrats to dominate the judiciary. In an attempt at politicization, a 2006 initiative in Montana was circulated permitting the recall of a judge “for any reason acknowledging electoral dissatisfaction.” Due to fraud uncovered in the collection of signatures, the measure was removed from the ballot prior to the election.49

In yet another case, state legislators, unhappy with some court decisions made in Missouri, introduced legislation to reduce the initial term of service for appellate judges from 12 to five years, and require a two-thirds voter majority rather than a simple majority for retention. Clearly, in the balance between judicial independence and popular accountability, it is likely that parties that disagree strongly with the decisions of their state courts will in some cases seek to limit the independence of the courts and create a judicial selection process more likely to put judges of their own liking on to state and local benches.

Nowhere has the politicizing of courts and the judiciary been more apparent than in judicial elections, especially in partisan elections. It was the 2002 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White that accelerated the politicizing of judicial elections. Prior to White, judicial candidates in Minnesota, which used the nonpartisan election process for judicial selection, were forbidden by Canon 5 of the Minnesota Code of Judicial Conduct from announcing their views on disputed legal or political issues, from affiliating themselves with political parties, or from personally soliciting or accepting campaign contributions.50 In the White case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the three clauses of Canon 5 violated the First Amendment rights of judicial candidates, and in so ruling invalidated them and all comparable limitations in place to other states.

The decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the White case made nonpartisan judicial election processes nonpartisan in name only. Judicial candidates in states featuring judicial elections can now personally solicit campaign funds from lawyers or litigants, they can engage in partisan political activities, and they can declare their views on virtually any matter of public concern – whether or not the matter may be the subject of current or future litigation brought to the court. While Canons of Judicial Conduct continue to exist in all states, the ability of a state Supreme Court or state Bar Association to sanction a judicial candidate for violating such professional and ethical standards has been undermined by the White decision.

Partisan elections, as noted previously, are increasingly becoming more like those of the other two branches of government – namely, expensive, mass media oriented, and rancorous. Surprisingly, in recent years the most expensive elections have been “retention-only” elections where voters only need to decide whether or not to keep a judge in office. In 1986 almost $12 million was spent in California to remove the state Supreme Court’s Chief Justice and two or her colleagues because of their opposition to the death penalty and because of the claim that they were “soft on crime.”51 In an obvious case of conflict of interest, plaintiffs in a $25 million punitive damages suit made contributions to two of the state’s Supreme Court Justices who were up for re-election and scheduled to hear the case; the justices refused to recuse themselves — or refrain from participating because of a conflict in interest — and ruled in the favor of the plaintiffs.

Special interests are more visible in judicial elections today than ever before; the most visible and active are those with the financial resources to “contribute” and with the most to win or lose in decisions made by courts. For example, the Ohio Chamber of Commerce spent $3 million to defeat a judge who had overturned a tort reform law worth many times as much for business; trial lawyers and unions spent about $1 million in a counteroffensive to retain the judge in question on the Ohio court.52 Large amounts of funding, and tides of negative advertising can be attributed to efforts by special interest groups to pursue their policy agenda. The ongoing fight between large corporations and plaintiffs’ attorneys over tort reform is a current source of potential politicization.

Despite the presence of strong pressures to further politicize the courts and the judiciary, the public’s general perception of the courts is still generally one of presumed independence and impartiality. A national public opinion survey conducted in 2005 found that while the public’s knowledge of the judiciary is rather poor, its belief in their courts’ adherence to the original principles of Themis are strong.53 Americans believe that their courts represent fairness, due process, impartiality, and play a key role in the preservation of citizen rights. Furthermore, 61 percent of the respondents to the 2005 survey believe that “politicians should not prevent the courts from hearing cases, even on controversial issues such as on gay marriage, because the purpose of the courts is to provide access to justice to everyone, even those with unpopular beliefs.”54

Exercises

Courts – What Can I do?

- Find out more about state governors by visiting the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) website at http://www.ncsconline.org/ (inactive link as of 05/19/2021) and consider taking one of their free online courses on state judicial issues at http://www.ncsconline.org/D_ICM/freeresources/index.asp (inactive link as of 05/19/2021)

- Visit NCSC’s states homepage to learn more about your own state’s court system:http://www.ncsconline.org/D_kis/info_court_web_sites.html (inactive link as of 05/19/2021)

- Consider visiting your local county or city court and watch the proceedings. Many court activities and trials are open to the public. Locate your local county or city court through the National Association of Counties website (http://www.naco.org/), the International City Managers Association (http://icma.org/), or the U.S. Courts website (http://www.uscourts.gov/courtlinks/).

8.F – State and Local Courts and Sustainability

The judicial branch may not “hold the sword” as does the executive branch, nor “command the purse” as does the legislative branch, but contrary to Alexander Hamilton’s view, it does have great influence over American society. In many areas of American life, the courts have fostered needed change when the “political branches” could not do so. In the areas of freedom of speech, racial equality, business regulation, the rights of the accused, and environmental protection, the victories made along the way were often seen not in legislation, but rather in the American courts. State and local courts may be somewhat reluctant participants in the public policy process, but they do have an important role as policymakers nonetheless. Judges are called upon to exercise judicial review of both the legislative and executive branches, interpret laws and constitutions, and make judicial policy. While unified state courts ensure a high level of consistency in the operation of courts, the decentralized operations of local courts make it possible for judges to become key actors in local political life by dealing with litigation reflecting local social, economic, environmental and political conflicts in impartial and constructive ways. Many of the decisions trial court judges make have the potential of establishing important policies affecting local practices in such important areas as zoning, public access to information, the provision of legal services to indigents, permissible policing practices, and equal access to education.

Cases heard in local trial courts can have an important impact on sustainable development throughout the nation; the most recent such case is that of Kelo v. City of New London, Connecticut. The case in question, as with the Dolan case from Oregon discussed above, concerned Fifth Amendment rights set forth in the U.S. Constitution. The controversial issue arose when the City of New London chose to use its power of eminent domain to condemn some private homes so that the property on which they sat could be used as part of the city’s economic development plan; a plan would result in this private property being condemned for use by another private party working in concert with the City of New London. The homeowners on the property in question filed a lawsuit in which they challenged the right of the City of New London to exercise its power of eminent domain for this purpose, and their case moved all the way from Connecticut trial and appellate courts to the U.S. Supreme Court. A majority of justices on the U.S. Supreme Court found that the benefits to the community involved justified the condemnation and that the City of New London had provided just compensation for the loss of property suffered by the affected homeowners.

In reaction to this decision, many state legislatures viewed the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision as too greatly benefiting large corporations at the expense of families and neighborhood communities. As a result, legislation was introduced in several states and ballot measures were placed on the ballot in other states aimed at amending state constitutions to provide greater protection of private property rights from this type of use (i.e., economic development) of the municipal power of eminent domain. That power is typically employed when there is some pressing need for public ownership of some private land to serve clearly public purposes (for example, creating a roadway for traffic control).

Some could say the City of New London’s action condemning some private land for the economic benefit of the entire community represents an action in line with the philosophy of sustainability since economic vitality is one of the pillars upon which sustainability rests. Others might argue that such actions threaten sustainability because they displace neighborhoods and promote social inequity in the form of privileged access to large, outside corporate interests. Such varied interpretations are clearly possible, and it is certain that more court cases such as this will be filed and heard as a consequence of municipal actions taken to promote economic viability coming into conflict with property owners seeking to preserve the current use being made of the land in question.

The Kelo case has caused the strengthening of private property rights in many states because this is a politically popular (and apparently cost-free) action for elected officials to take. However, by strengthening private property rights, states enacting greater protections to homeowners may make it more difficult to promote sustainable development. For example, should a municipality seek to use its power of eminent domain to locate solar collectors to provide cheaper and renewable energy to its utility subscribers, should private property owners adversely affected by the location of those collectors be allowed to prevent such a use of eminent domain? Should the pursuit of sustainability goals be one of the “reasonable grounds” justifying the use of eminent domain in the states where laws more protective of homeowners’ rights were enacted in the wake of the Kelo case? One thing is for certain, state court and the judges sitting on trial court and appellate court benches in our states will be hearing just such cases in the years ahead.

State and local courts have impacted sustainability in the past, and they will most certainly do so in the future. Generally speaking, the higher the level of the court, the larger the swath of impact its actions have on sustainability. If a state’s Court of Last Resort makes a precedential ruling, then the state’s lower courts must follow the dictates of that ruling. This is not to say trial courts are unimportant, as they are most often the first to hear a case that could lead to a change in the law, good or bad, around the rest of the state. Illustrative of the importance of courts in the area of sustainability promotion in state and local government, the case of the widowed grandmother in Orem, Utah stands out. This elderly woman was arrested and taken away in handcuffs for refusing to give a policeman her name so he could issue her a ticket for failing to water her lawn on a regular basis, a violation of an Orem zoning ordinance. If the case goes to trial, it would be heard in the Orem Municipal Court. The reason the grandmother provided for not watering her lawn was that of inability to afford the expense associated with maintaining a green lawn. However, the national attention generated from the case has led to question as to why someone should have to defend themselves in court for a practice that is both uneconomical and wasteful of a precious natural resource – particularly since Utah is the second driest state in the nation.

8.G – Conclusion

There are two clear areas within the purview of state and local courts which can impact sustainability in a major way, and those would be Judicial Federalism and the maintenance of judicial impartiality. Judicial Federalism is a legal term referenced earlier which characterizes situations in which state courts give priority of a state question addressed in state constitutional law over a federal question addressed in federal constitutional law. In the recent past, Judicial Federalism has focused on enhancing the civil rights of a state’s vulnerable minorities (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities, the criminally accused) beyond the rights provided in the U.S. Constitution. Today, in the context of the need to address global climate change and actively pursue sustainability, Judicial Federalism could expand its purview to include the protection of other vulnerable environmental minority interests such as wildlife, water resources, ecosystem services, and rural communities. The well being of these interests coincide with the economic and social vitality of local communities, and their interests could be served more flexibly in state law than in federal rules and regulations. In order for Judicial Federalism to be able to work in this area, the state legislatures must refine their constitutions and statutes to reflect the states’ desire to pursue sustainable development so that judges in state and local courts can do their part to support public and private actions intended to promote sustainability.

The second area of particular concern, that of the maintenance of judicial impartiality, requires judges and their courts to be independent from outside influences, making decisions based on legal principles, fairness, and equity as opposed to the provision of special consideration based on political party or privileged interest. As much as Americans would love to maintain their current belief in the ideal of blind justice, human fallibility will always be present. The recent trends toward a politicization of the courts and the judicial selection process bought on in the wake of the White decision open the door to the possibility that private interests that benefit from unsustainable practices – such as urban sprawl, sole reliance upon automobile travel for transportation, over-harvesting of forests and excessive extraction of natural resources – will seek to “plant” judges friendly to their interests on state trial and appellate court benches. Efforts are needed by those who support the goals of sustainability to promote both the independence of their state and local courts and to stem the rising tide of the politicization of courts and the judiciary.

Terms

Administrative Law Judges

Certiori

Common Law

Dual System (judicial power)

Eminent Domain

General Jurisdiction Courts

Judicial Federalism

Mandate of the Court

Merit System of Judicial Appointment (see “Missouri Plan”)

Missouri Plan

Politicization of Courts/Judiciary

Trial Courts

Unconstitutional Taking

Exercises

Discussion Questions

1. Of the two common methods of judicial appointment — gubernatorial appointment and the merit system (Missouri Plan) — which do you think is the best method and why? Is it really possible to remove “politics” out of judicial appointments?

2. What are the various types of state and local courts and what functions do they serve? How about problem solving courts — do they increase the institutional sustainability of communities?

3. What are some of the current and potentially future challenges facing state and local court systems? Do you think the politicization of judicial processes will increase or decrease in the future? Why?

Notes

1. A. Hamilton, “The Federalist No. 78: The Judiciary Department,” Independent Journal, June 14, 1788.

2. D.B. Rottman, “The State Courts in 2005: A Year of Living Dangerously.” In The Book of the States, 2006 (Lexington: The Council of State Governments).

3. G.C. Edwards, M.P. Wattenberg, and Robert L Lineberry. 1998. Government in America: People, Politics, and Policy, 8th ed. (New York: Longman).

4. Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. 2007. Understanding Federal and State Courts 2007 [cited Dec., 25 2007]. Available from website http://www.uscourts.gov/ outreach/resources/fedstate_lessonplan.htm

5. H.J. Abraham, Henry Julian. 1998. The Judicial Process: An Introductory Analysis of the Courts of the United States, England, and France (New York: Oxford University Press).

G.C. Edwards, M.P. Wattenberg and R.L. Lineberry, 1998, op. cit. (see reference 3).

6. H.R. Glick, R. Henry and K.N. Vines. 1973. “State Court Systems.” W. S. Sayre, ed. Foundations of State and Local Government (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall).

8. C. McGowan, The Organization of Judicial Power in the United States (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1967), p. 37.

9. G.C. Edwards, M.P. Wattenberg and R.L. Lineberry, 1998, op. cit. (see reference 3).

10. Rottman, David B, and Shauna M Strickland. 2006. State Court Organization, 2004. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

12. Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, 2007, op. cit. (see reference 4).