Wildland Fire Policy and Climate Change

Evolution of Fire Policy and Current Needs

Eric Toman

Introduction

Wildland fires have long shaped the western United States, influencing the type, density, and arrangement of vegetation across the landscape. Since the early days of habitation in the region, humans have grappled with how to live with fire. On one hand, wildfires can lead to harmful effects to human settlements and cause near-term ecological damage. On the other hand, fire plays an important ecological role and in many cases serves to maintain the health of natural systems and the provision of key ecological services. Beginning in the early 1900s, wildland fires were primarily viewed as destructive events that posed substantial risk to the growing human population in the western United States, and efforts to suppress fires were prioritized. As time progressed, recognition of the ecological benefits of fire grew and caused some to reevaluate the emphasis on fire suppression. Moreover, as has become clearer in recent years, our success in removing most fires from the landscape has served to increase the risk of catastrophic fires, largely owing to an increase of vegetative material that acts as fuel. These increased fire risks are further amplified by the changing climate, which has contributed to developing fire-prone conditions. It is in this context that many researchers and managers have called for a new paradigm of how we think about and live with fire in the western United States (e.g., Calkin et al. 2011; Dombeck et al. 2004; Thompson et al. 2018).

Today’s forests, grasslands, and other undeveloped landscapes that we think of as natural are in actuality a product of human influences. Ultimately, decisions about preservation, harvest, development, access, and use have all played a role in the development of our “natural” landscapes. Perhaps most influential are decisions that result, intentionally or not, in suppressing or amplifying ecological processes, as these decisions may lead to large-scale and long-term ecological changes. In this chapter we consider the complex and interacting effects of policy and management related to wildland fire on current and potential future conditions. We begin by considering the current state of wildland fire management and expected effects of climate change. Then we describe the evolution of wildland fire policy and how this has influenced conditions on the ground. The chapter concludes by considering policy and management actions that can contribute to increased resilience of natural and social systems given current and expected future conditions. A quick note on terminology: in this chapter we follow the phrasing used within the wildfire management community (table 5.1).

Current Context: Wildland Fire Policy and Management

Wildland fire management is a high-stakes endeavor and has long been viewed as central to the mission of federal natural resource management agencies (namely, the US Forest Service in the Department of Agriculture and the National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior). There is no singular statute or existing legislation that sets specific policy for wildland fire. But because a number of federal, state, and tribal agencies and organizations are involved in wildland fire management, a robust structure has been developed with representatives across agencies to develop and coordinate federal fire policy and management guidelines. These coordination efforts seek to provide consistency in general policy based on an agreed-upon set of guiding principles, common definitions for relevant terminology, and agreements for managing specific fire events, including the command structure for decision making, agreements regarding sharing resources, and allowing personnel to work across jurisdictional boundaries (US Department of the Interior Office of Wildland Fire 2017).

Table 5.1. Wildland Fire Terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Prescribed fire | Any fire intentionally ignited by management actions in accordance with applicable laws, policies, and regulations to meet specific objectives. |

| Wildfire | An unplanned, unwanted wildland fire, including unauthorized human-cauased fires, escaped wildland fire use events, escaped prescribed fire projects, and all other wildland fires where the objective is to put the fire out. (Note: this definition is currently under review.) |

| Wildland | An area in which development is essentially nonexistent, except for roads, railroads, powerlines, and similar transportation facilities. Structures, if any, are widely scattered. |

| Wildland fire | Any nonstructure fire that occurs in vegetation or natural fuels. Wildland fire includes prescribed fire and wildfire. |

Definitions from National Wildfire Coordinating Group (2019)

Wildland fire policy has evolved substantially since the early 1900s. Initial policy strictly emphasized the control and suppression of all fire. Although such efforts were largely successful in the near term, this emphasis on excluding fires from the landscape has actually served to increase the risk of future wildfires, a situation often referred to as the wildfire paradox, as management efforts to suppress wildfires led to a buildup of vegetation (e.g., fuel for wildfires) and increased continuity between existing fuel (allowing for fire to be carried along the surface or into the tree canopy) (Arno and Brown 1991; Calkin et al. 2015). The wildfire paradox illustrates the potential for differential outcomes of policy across scales of time and spatial extent. In many cases, the policy of fire suppression was successful at immediately extinguishing ignited fires, reducing the near-term and local risks of negative effects. Over time and at larger spatial scales, however, the success of fire suppression has actually resulted in increased vulnerability to future impacts across the landscape.

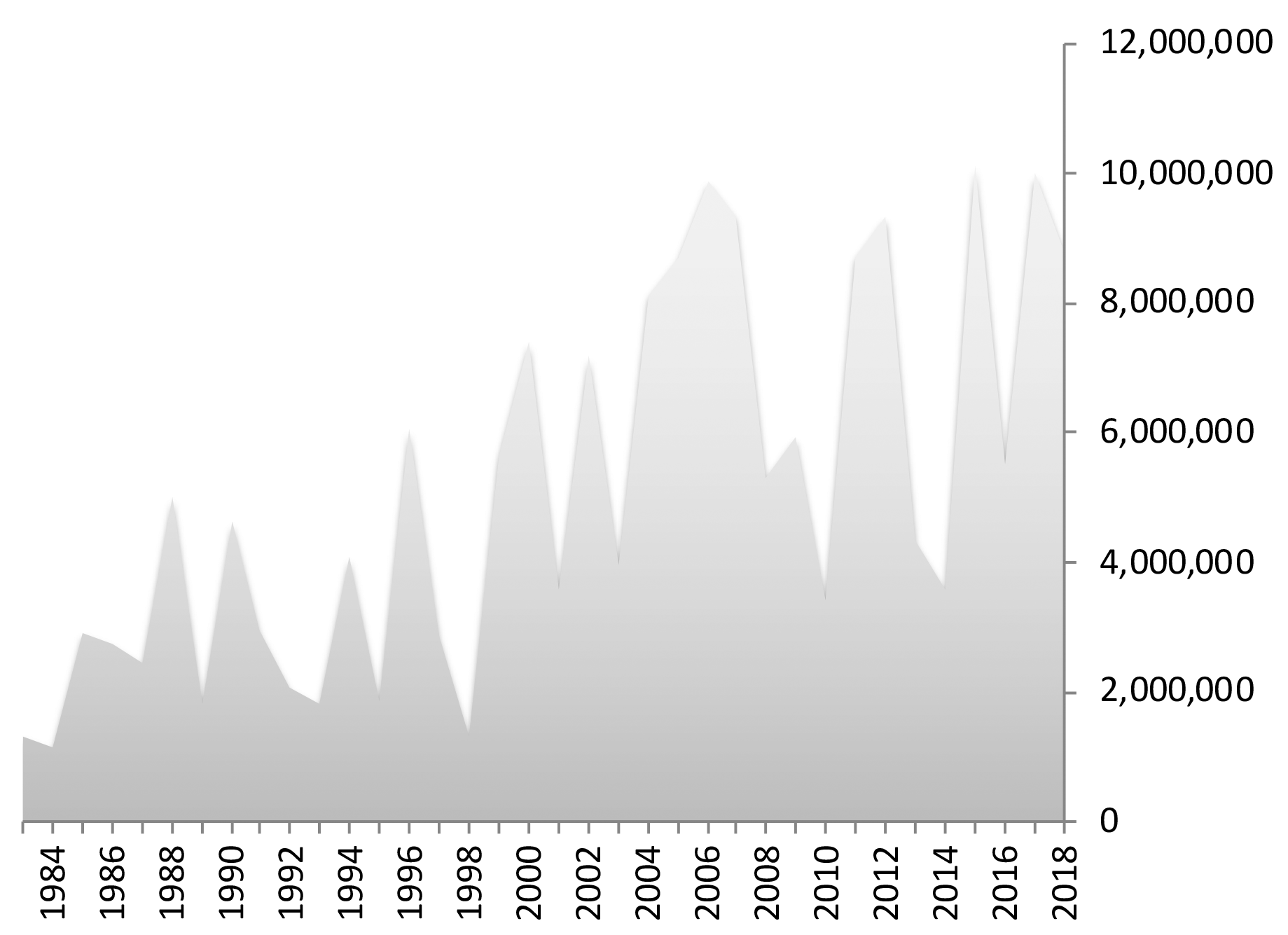

As illustrated in figure 5.1, the annual amount of acres burned by wildfires has increased over the last thirty-five years. The average number of acres burned annually increased over each of the last several decades (1980-1989, 2.98 million acres; 1990-1999, 3.32 million acres; 2000-2009, 6.93 million acres; 2010-2018, 7.09 million acres). These figures illustrate that these increases are not necessarily linear over time; rather, the average number of acres burned annually doubled between the 1990s and 2000s. Moreover, this increase has occurred despite the relative success of “initial attack” efforts, where aggressive suppression efforts that seek to extinguish wildfires immediately upon detection result in successfully extinguishing between 97% and 99% of fire starts (Calkin et al. 2005), and as record expenditures are spent on wildfire suppression with more than $2 billion in expenses in 2015 (for the first time) and exceeding $3 billion in 2018 (National Interagency Fire Center 2019a).

While research has long recognized the ecological benefits of fire and wildland fire policy has long allowed for allowing some naturally ignited fires to burn to achieve resource benefits, in practice, most ignitions are still treated with aggressive initial attack efforts (Calkin et al. 2015). This begs the question: If aggressive wildfire suppression efforts are limited in their ability to prevent losses and protect communities, why are these approaches still emphasized? Surprisingly, a relatively limited number of studies have examined the wildland fire decision-making context; however, findings to date do suggest some key points. Ultimately, wildland fire management decisions are made within a complex context. From a policy perspective, wildland fire management decisions are not only subject to guidance provided by overarching fire policy, but must also comply with a suite of other relevant laws and resulting agency policy. In any given situation, fires may affect water and air quality (regulated by the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act) or have impacts on protected or sensitive species protected by the Endangered Species Act (directly through harming individuals or through negative impacts to their habitat). Wildland fires that pose a potential threat to valuable resources substantially raise the stakes regarding their management, particularly if homes or private property are at risk. Understandably, such situations may lead to an emphasis on aggressive suppression efforts; however, Stephens et al. (2016) argue that this may lead to “tunnel vision,” where fire management decisions are evaluated solely on the expected negative outcomes to specific, valued resources. Similarly, other researchers have found that wildland fire management decisions may be biased toward local and near-term impacts rather than longer-term outcomes at larger spatial scales (Thompson 2014; Wilson et al. 2011). This tendency toward discounting long-term risks compared to short-term risks is not limited to fire managers but is common in decisions including risk and uncertainty, and thus will require intentional intervention and support to overcome (e.g., Maguire and Albright 2005; Wilson et al. 2011).

Further complicating the decision-making environment, in addition to the risks posed to resources, managers must also weigh the potential for personal liability or negative impacts to their career if they decide to engage a wildland fire less aggressively (Calkin et al. 2011; Donovan et al. 2011). Aggressive fire suppression is likely to be viewed as more defensible if negative impacts occur (Ager et al. 2014). Ultimately, these cumulative influences provide substantial incentive to aggressively suppress fires and may limit the ability to consider the effects of such decisions on long-term risks to desired ecological conditions or the risks posed to communities despite the potential for such an approach to negatively influence the resilience of human and natural systems (Stephens et al. 2016).

Climate Change and Wildland Fire

While the wildland fire decision-making context is exceedingly complex, it is further complicated by impacts resulting from ongoing climatic changes. Climate is a key driver of wildland fire activity (Schoennagel et al. 2017). Historical reviews have illustrated a strong association between wildfire activity and climate variables—particularly temperature and drought (Marion et al. 2012; Westerling et al. 2006; Whitlock et al. 2008). Not surprisingly, one of the primary ways climate change influences wildfire is through alterations in weather patterns. These changes may result in both near- and long-term impacts. In the near term, increased temperatures, extended heat events, or decreased precipitation can increase the risk of wildland fire activity. Over the longer term, changes in temperature and precipitation can influence the suitability of growing conditions for particular species (Vose et al. 2018) and lead to increased mortality directly (e.g., vegetation dying from a lack of adequate precipitation) as well as indirectly through changes in the incidence of and susceptibility to pests and disease. In other words, a changing climate can stress the natural vegetation historically present in a given location and lead to a die-off as the current conditions no longer meet the needs of the vegetation (e.g., inadequate supply of water), while the remaining stressed vegetation may be less able to defend against pests and disease.

Some recent cases illustrate how the effects of climate change may interact with other disturbance events with the potential to result in unprecedented impacts to forested ecosystems. Vose et al. (2018) illustrate the potential interactive effects of disturbance events by reviewing recent changes in Sierra Nevada forests. Their review illustrated how five years of drought (ending in 2017) weakened trees and made more them susceptible to substantial bark beetle outbreaks. Overall, more than 129 million trees were killed across 7.7 million acres between 2010 and 2017. Impacts were particularly acute in some locations, with up to 70% mortality in a single year. The western pine beetle was the primary insect responsible for these losses. Given that the pine beetle primarily targeted ponderosa pine trees, this outbreak contributed to changing the composition of local forests by shifting from a ponderosa pine-dominated system to one dominated by incense cedar. The mortality and shifting species were expected to contribute to an increased risk of high-intensity surface fires and larger wildfire events (Stephens et al. 2018).

Similar trends are apparent across the western United States. While pine beetles and other pests are native to many western forests, their populations and their associated impacts are typically limited, at least in part, by the typical climatic conditions. In many western forests, winter temperatures were previously cold enough to reduce pine beetle populations; however, warming temperatures in recent years have resulted in increased beetle populations with a concomitant expansion in the number of acres affected by pine beetles (affecting more than 25 million acres in the western United States since 2010) (Vose et al. 2018). Increased tree mortality leads to an increased risk of wildfire as more fuel is available to burn.

As these examples illustrate, conditions in many forests throughout the western United States are changing. Reviewing the current body of research, Vose et al. (2018) concluded that the frequency and magnitude of severe ecological disturbances, including wildfire, were expected to lead to rapid and potentially long-lasting changes in forest structure (species present and their composition) and function (the ecological services they provide). These changes illustrate a need to shift how we think about fire. The current approach to fire management has been developed on the basis of historical trends, as past fire occurrence, behavior, and intensity are considered as proxies to estimate future wildfire events and likely outcomes. While there has always been substantial variability in actual wildland fire activity in any given year, conditions have occurred within a range of historic conditions. But recent years suggest that we may be entering a new era of wildfires where expectations based on historic trends no longer apply (Schoennagel et al. 2017).

As one example, the “fire season” (the annual period during which forest conditions were particularly conducive to wildfires and when most historical wildfires occurred) has grown longer in recent years owing to increased temperatures and earlier snowmelt (Gergel et al. 2017; Westerling et al. 2006). At the same time, summer drought conditions have intensified and increased wildfire risk (Dennison et al. 2014; Littell et al. 2016). Substantial research suggests fire occurrence will continue to increase in future years with specific changes depending on local conditions (e.g., Hawbaker and Zhu 2012; Litschert et al. 2012; Littell et al. 2016).

The last few fire seasons illustrate how destructive this new era of wildfire may be. Early 2017 began with above-normal precipitation west of the Rocky Mountains (National Interagency Coordination Center 2018). While the increased precipitation was welcome, particularly in California, as it came on the heels of a prolonged drought, precipitation rates exceeding 200% of normal led to challenges of its own, including threatening a near-catastrophic failure of the Oroville Dam in February 2017 (leading to the evacuation of more than 180,000 people) (National Interagency Coordination Center 2018). Moreover, this early-season precipitation contributed to the growth of substantial fine fuels (including grasses, needles and leaves) less than one-fourth of an inch in diameter, which can dry quickly and ignite rapidly, contributing to increased fire risks later in the season (National Wildfire Coordinating Group 2019). Above-average precipitation continued throughout much of the spring and summer in Northern California.

In their annual summary of the fire season, National Interagency Coordination Center (2018) described summer 2017 as “historically unique” with “an abrupt shift in the weather pattern” in early July, leading to excessive heat events, earlier melting of mountain snowpacks, and drying out the above-average amounts of fine fuels. Many parts of the country experienced above-average fire activity across the year (153% of the ten-year average in terms of acres burned). Disaster response resources were further stretched by the impacts of several hurricanes (Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria) on Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and particularly Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands in August and September. While autumn weather brought decreased temperatures and increased precipitation to much of the western United States, California remained drier than usual. These dry conditions combined with wind events contributed to the development of several large wildfires, including the Thomas Fire that burned 281,893 acres (at the time the largest fire in California history) and the Tubbs Fire that burned 36,807 acres and 5,643 structures and resulted in twenty-two fatalities). In California alone, 11,012 structures were lost to wildfires in 2017, far exceeding the national average of 2,836 structures lost annually. Further illustrating the interactive nature of climate, fire, and weather influences, subsequent autumn rain fell on a landscape where much of the existing vegetation had been removed. This led to substantial erosion and, in some tragic cases, mudslides and debris flows that contributed to a further twenty-one fatalities in January 2018.

Winter 2018 again saw substantial variation in precipitation rates across the West, with above-average precipitation in the eastern and northern United States (mountain snowpack 200% of normal in northern Rocky Mountains) but lower-than-average rates in the Great Basin, California, and Southwest (mountain snowpack 50% of normal) (National Interagency Coordination Center 2019). Weather patterns in the West generally followed expected trends, with the exception of the drought conditions that persisted in the coastal states through summer and autumn (National Interagency Coordination Center 2019). The wildfire season was active, with an above-average number of acres burned (8,767,492 acres; 132% of the ten-year national average). California again experienced substantial wildfire activity, including the Mendocino Complex Fire that burned 459,123 acres (the largest fire in California history). Similar to 2017, two late-season wildfire events were particularly destructive. Ignited on November 8, the Woolsey Fire burned 96,949 acres and gained national attention as it burned through expensive neighborhoods and destroyed the homes of several celebrities in Malibu, California (1,643 structures were lost while three fatalities occurred). Ignited on the same day, the Camp Fire quickly burned through the community of Paradise in Northern California, burning 153,336 acres, destroying 18,793 structures, and resulting in eighty-six fatalities (CalFire 2019). The Camp Fire exhibited extreme fire spread, moving at a rate of 80 acres per minute, leaving little time for residents to evacuate (National Interagency Coordination Center 2019). The Camp Fire was the deadliest wildfire in the past century in the United States (National Interagency Coordination Center 2019) and was the costliest worldwide natural disaster in 2018 (estimated losses of $16.5 billion) (Löw 2019).

Wildfire Management Context: The Wildland-Urban Interface

As the above discussion illustrates, climate variables exhibit a strong influence on wildfire. Ongoing changes in these climatic variables have already and are expected to continue to lead to changes in wildfire activity, intensity, and impacts. Further complicating matters, the emphasis on fire suppression over the past century has modified forest conditions and in many cases has heightened the risk of future wildfires. On their own, these changes would heighten the importance of adapting current wildland fire policy to address these new conditions. As recent fire seasons in California illustrate, however, wildfire events result in severe impacts not only to forests but also to human communities.

Critical to any new approach to address our current wildfire problem in the United States is a better understanding of how to address fire in what has come to be known as the wildland-urban interface (WUI), defined as “areas where houses meet or intermingle with undeveloped wildland vegetation” (Federal Register 2001). Across the country, 9.5% of the US land area is classified as WUI, with substantially higher levels in some locations (Radeloff et al. 2018a). Recent analyses indicate that the WUI is growing. Between 1990 and 2010, land classified as WUI grew by 189,000 km2 (“an area larger than Washington State”) while adding 12.7 million houses and 25 million people (Radeloff et al. 2018b). Moreover, the rate of growth is high (33%) and exceeds the growth rate of other designated land types.

Many of the most destructive wildfires in recent years have occurred in the WUI. The impact of a wildfire cannot be fully appreciated by the number of acres burned, as even relatively “small” wild fires in WUI areas can affect thousands of residents and threaten communities even though they may have a limited spatial extent. Moreover, wildfires burning in the WUI are more complicated to manage and may result in increased risk to firefighters because they may be managed more aggressively to avoid potential loss of life and property among local residents. Not surprisingly, there is a positive correlation between proximity of WUI communities and suppression costs; suppression costs increase the closer wildfires occur to communities (Fitch et al. 2017).

Policy and Management Approaches to Address Current Wildfires

Ultimately, while wildfires are a natural disturbance in western forests, fire occurrence, behavior, and resulting impacts are influenced directly and indirectly by human factors. Today’s fires burn within a human-dominated landscape, as current forest conditions represent the legacy of past management decisions as well as changing temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and prevalence of pests driven by ongoing climatic changes. Moreover, wildfires burning within this context are likely to have the potential for both greater ecological (owing to burning with a greater intensity than was typical) and human impacts (given the growth of the WUI and private development within natural landscapes). The interactive effects of these changes have resulted in a particularly complex reality for contemporary wildfire management. This begs the question, Does current wildfire policy provide sufficient guidance to successfully manage current wildfire challenges?

To address this question, in the following section we review the evolution of wildfire policy and management over time and consider the adequacy of current policy to address today’s wildfire management realities.

How Did We Get to Where We Are Today? The Evolution of Wildfire Policy

Since their very establishment, land management agencies have had wildfire management as central to their missions. In the earliest days of these agencies, fire suppression was considered a key tenet of professional forestry. Indeed, Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the US Forest Service, believed that it was a forester’s responsibility to control fires (Hays 1999) to conserve forest resources that were viewed as important for future development (Pyne 1997). While agency priorities have changed over time, as we describe below, wildfire management is still viewed as central to the ability to achieve broader agency goals.

Fire Policy from 1900 to 1960: Fire Exclusion

As European settlement advanced westward across the United States, undeveloped lands were largely viewed as providing a stock of valuable resources that could fuel the nation’s growth. Early natural resource management was focused on applying the most efficient methods to extract the resources of interest with little consideration of long-term impacts of this extraction. While it may be easy to find fault with such decisions now, it is important to recognize the broader context within which such decisions were made. At the time, there was limited understanding of the interrelated nature of ecological systems and how changes to one component could lead to a diverse range of future outcomes, including some that are relatively unintuitive (such as aggressive suppression of wildfires in the short term, leading to larger and more destructive wildfires in the future). Moreover, throughout much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a large portion of the US population relied directly on natural resource extraction and use for their livelihoods. The sheer vastness of the undeveloped land contributed to what has been referred to as the “myth of superabundance”—a belief that resources were so plentiful that they could never be exhausted by development (Callicott 1994).

This began to change in the late nineteenth century as impacts began to emerge from previous land management practices during the western expansion of European civilization. Forested lands in the northern lake states (portions of Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin) experienced extensive and often wasteful logging (Williams 1989). The standard logging practices of the time consisted of removal of the valuable trees while leaving behind substantial woody material, including less desirable tree species as well as branches and debris from harvested trees (material known as “slash” to foresters). This slash would dry out and become a substantial fire hazard, creating the potential for catastrophic fires.

The deadliest wildfire in US history occurred under such conditions. On October 8, 1871, a wildfire burned through Peshtigo, Wisconsin, and several other small communities, resulting in more than a thousand fatalities. Although specific estimates vary, the fire is thought to have burned nearly one million acres, quickly moving through the slash left in harvested areas. While devastating to those who experienced the fire firsthand, the fire did not garner widespread popular attention—indeed, it was largely overshadowed by the Great Chicago Fire that occurred on the same day. In the end, the Peshtigo Fire resulted in limited introspection about how common management practices of the time may have contributed to the impacts.

While several wildfires occurred in the subsequent years, the next fires recognized for their historical impact took place forty years later in several locations across the western United States. Spring 1910 saw snows melt earlier than normal, while precipitation amounts were lower than average. Several fires were ignited throughout the summer from natural (lightning) and human sources (including inadvertent fires started by homesteaders and sparks from coal-powered locomotives) (Egan 2009). By midsummer, several wildfires burned across the western United States as drought conditions continued to worsen. Estimates vary, but it is thought that between 1,700 and 3,000 wildfires were burning in early August in northern Idaho and western Montana (US Forest Service n.d.). The US Forest Service, at the time a relatively new and controversial agency established only five years earlier, in 1905, assembled several crews of rangers, miners, foresters, and military troops to combat these fires, prevent a loss of valuable timber, and protect the developing human settlements in the region, primarily timber towns developed to support the extraction, processing, and shipping of timber products. The firefighting crews were estimated at close to 10,000 strong, and they had largely been effective at containing the wildfires through much of the summer (Busenberg 2004). But things changed dramatically on August 20, as gale-force winds swept across the region, causing several fires to escape containment. Over the next two days, new wildfires started, merged with others, and burned across the landscape while the laboring crews did everything in their power to slow and direct their spread. Eighty-six people were killed as the wildfires burned an estimated three million acres. Entire towns were destroyed, and billions of board feet of valuable timber were consumed in Idaho, Montana, and Washington in two days (Egan 2009). The scale of the wildfires and the resulting impact captured national attention in a way the Peshtigo Fire had failed to do. Since its founding just five years earlier, there had been substantial debate regarding the value of the US Forest Service, with many western residents and elected representatives actively arguing for the agency to be dissolved (Egan 2009). Yet the narrative emerging from the 1910 wildfires provided a rallying point for supporters of the agency, including Chief Gifford Pinchot and his ally, US President Theodore Roosevelt. The agency emerged from this period with increased support for its mission of conserving forestlands for the long-term benefit of the nation. Wildfires were viewed as destructive events that not only threatened the life and safety of residents and those working in the forests but also wasted valuable timber needed to continue to fuel the nation’s development (Pyne 2001). Congress soon passed legislation (Weeks Act of 1911) that gave the US Forest Service substantial power in shaping national wildland fire policy by creating financial incentives for states to cooperate with the agency in pursuing an aggressive approach to suppress wildfires as well as an ability to draw on an emergency budget to support fire suppression (Busenberg 2004).

Considering the impact of the 1910 wildfires, it is not difficult to understand how the dominant paradigm came to consider wildfires almost exclusively as destructive events that posed both near- and long-term threats to the nation (however, even at this early time there were some dissenting views from the Southeast and West Coast that advocated for the use of fire as a management tool; see van Wagtendonk 2007 and Smith 2017 for additional discussion). From this perspective, fire exclusion (extinguishing all fires as soon as possible after ignition) was viewed as the most rational approach to wildland fire management. Over the next several years, the US Forest Service as well as other federal and state natural resource management agencies continued to improve their efforts to prevent the ignition of fires through public education campaigns and development of equipment, infrastructure, training, and a robust command and control structure designed to suppress all wildfires as soon as possible. In 1935, the US Forest Service formalized the fire exclusion policy that had been operating in practice in what was referred to as the “10:00 a.m. policy,” which directed that all fires would be extinguished by ten o’clock in the morning on the day following detection (van Wagtendonk 2007).

In the near term, these efforts proved largely successful, and the average annual acres burned declined substantially throughout the twentieth century, particularly after the new equipment and workforce developed for World War II were engaged actively suppressing wildland fires (Busenberg 2004; National Interagency Fire Center 2019b). But evidence began to emerge of unintended consequences of the fire exclusion policy. In the 1960s, scientists and managers began to associate ecological changes such as increasing tree density and limited regeneration of some desirable species, among others, with the absence of fire (Agee 1993; Bond et al. 2005). Emerging scientific research began to illustrate a more complex view of the role of fire in developing and maintaining forest systems (Agee 1997). It was increasingly recognized that fire played an important role in managing competition between vegetation, with different species gaining an advantage depending on the frequency or intensity of fire events. For some tree species, fires are required for regeneration because heat is needed to open their cones to release seed.

Evidence also began to emerge that the vegetative changes resulting from wildland fire suppression may actually serve to increase future fire risks. Specifically, fire suppression allowed for a buildup of flammable material (woody debris, dead trees, needles, etc.) as well as an increasing density of live vegetation, providing a pathway for ignited fires to extend from the forest floor to the tree canopy (Agee 1997; Dombeck et al. 2004). Thus there was increasing recognition that while fire exclusion may reduce near-term risks, the resulting vegetative changes actually made the forests more vulnerable to destructive fires and a loss of valuable timber as well as increase risk to human communities in the long term. Such outcomes were in direct opposition to the goals of fire suppression, contributing to more questions about the legitimacy of the fire exclusion policy (Busenberg 2004).

Land management priorities also expanded within the twentieth century to reflect the growing understanding of ecological systems and increasing public concern for environmental protection. Several environmental laws established in the middle of the twentieth century exemplify the broadening priorities of agency management. Some notable laws are highlighted in table 5.2 below. Although these laws do not expressly determine agency policy toward wildland fire, wildland fire management activities are expected to be compatible with and contribute to achieving the specific goals identified within these laws. Moreover, forest management plans mandated for development on a rolling basis by the National Forest Management Act also include guidance for wildfire management decisions in all national forests. Importantly, no specific federal statute establishes wildfire policy (Stephens et al. 2016); rather, wildfire policy is developed through designated interagency committees consisting of senior personnel with final review and approval granted by agency leadership (US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior 2009).

Fire Policy from 1960 to 2000: Experimentation with Limited Fire Use

Although fire exclusion was the dominant paradigm of wildland fire policy and management throughout the early twentieth century, some practitioners and scientists outside this mainstream perspective advocated for alternative approaches to fire management. Early research reported that some residents were using intentionally ignited fires to manage vegetation and reduce the potential for destructive wildfires (Hough 1882). Even after the 1910 fires largely solidified belief in the destructive nature of fire within the US Forest Service, individual forest managers still experimented with intentional use of fire, then referred to as “light burning,” to manage vegetation (Smith 2017). This minority voice argued for the importance of better understanding and applying light burning to protect and maintain desired forest resources and reduce the vulnerability of forest systems to more destructive fires. As recognition of the unintended consequences of fire exclusion increased more generally, this type of experimentation with limited use of fire began to increase.

Table 5.2. Subset of Key Laws Influencing Management of National Forests

| Law | Year Established | Brief Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Use and Sustained Yield Act | 1960 | Specifies that national forests should be managed for multiple uses, including timber, range, water, recreation, and wildlife. Gives additional priority to nontimber uses. |

| Wilderness Act | 1964 | Provides a mechanism to designate lands for protection with limited human development, including for management activities. Natural processes given priority. |

| National Environmental Policy Act | 1969 | Requires consideration of environmental impacts of management decisions. Requires consideration of public input in planning. |

| Endangered Species Act | 1973 | Designates species at risk of extinction and requires federal agencies act to protect and recover listed species. |

| National Forest Management Act of 1976 | 1976 | Requires strategic planning for national forests and grasslands. Provides direction for implementation of forest and wildfire management projects. |

The federal approach toward wildland fire began to shift on a larger scale the late 1960s. The Department of Interior created a committee to examine wildlife management issues in 1962. In their review, the committee began to apply emerging scientific information that recognized the interconnected nature of forest systems and advocated for using an ecosystem approach to management, including integration of natural disturbance processes such as wildland fire (van Wagtendonk 2007). In response to the committee’s recommendations, the National Park Service modified their policy to allow for some use of fire to achieve management objectives in 1968. Individual parks were then allowed to develop plans that had a more liberal approach to using fire. Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park was the first to implement such a plan (in 1968), and a few additional parks joined them over the next few years (Saguaro National Monument in 1971 and Yosemite National Park in 1972) (van Wagtendonk 2007). The US Forest Service had also begun to reevaluate their approach to land management following the 1964 passage of the Wilderness Act with its emphasis on preserving natural landscapes and processes. Like the National Park Service, the US Forest Service officially modified their policy to allow some use of fire in 1968 (Busenberg 2004). In 1972, the first wildland fire was allowed to burn to achieve resource objectives on Forest Service land in Montana’s Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Area. In 1978, the Forest Service officially moved away from the 10:00 a.m. fire suppression policy (van Wagtendonk 2007).

On the ground, implementation of these new policies typically included the development of wildland fire management plans that designated zones across the landscape, each with specified management alternatives ranging from suppression of all wildland fires in some areas to allowing naturally ignited fires to burn in designated areas while also allowing for management-ignited fires (typically referred to as prescribed fires) in some cases. In practice, most ignitions were still aggressively suppressed. This has led some authors to argue that the policy of fire exclusion was still largely applied, even as evidence emerged of its failure to achieve agency goals (see Busenberg 2004 for a discussion of how fire exclusion has been perpetuated as the dominant policy focus).

Over the next several years, wildland fires were managed under this hybrid approach and either immediately suppressed or, in limited cases, allowed to burn under predetermined prescriptions. Manager-ignited prescribed fires were also increasingly used as fire management programs began to develop. While some fires managed under these alternative approaches resulted in local-level impacts and caused some reconsideration of unit-level plans, there was little national attention paid to this shifting approach to wildland fire management until the 1988 fire season.

The summer of 1988 saw substantial fire activity in and around Yellowstone National Park. Given its iconic status as the world’s first national park, these fires garnered media attention, and people across the nation followed the daily reports provided by the major news networks. Much of the discussion emphasized that the fires had been allowed to burn both within Yellowstone National Park and on adjacent national forestlands for more than a month before suppression activities were ramped up (van Wagtendonk 2007). In late July, dry and windy conditions led to rapidly increasing fire, resulting in fire managers deciding to actively suppress the fires. By the time the fires were contained, over 1.3 million acres had burned in the greater Yellowstone area. The public response was overwhelmingly negative with charges of irresponsible management resulting in substantial damage to such a prized area (van Wagtendonk 2007).

The Yellowstone fires prompted the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior to complete a review of the then-current national fire policy. Overall, these reviews reaffirmed support for the natural role of fire in forested ecosystems but also identified shortcomings with current fire management plans (van Wagtendonk 2007). Secretaries of both departments suspended the practice of allowing naturally ignited fires to burn until steps could be taken to strengthen interagency communication and establish clear decision criteria for management decisions (Rothman 2007). Management use of fire declined in the subsequent years before beginning to increase again as time passed, and new, more robust management plans were adopted. Over time, the successful recovery of the Yellowstone forests has been touted as a success story of ecosystem management and an illustration of the resilience of forest systems even after severe disturbance (Stephens et al. 2016).

Wildland Fire Policy in the 2000s

Wildland fire policy continued with this similar hybrid approach through the 1990s. An additional fire policy review in 1995 described fire as a “critical natural process” that “must be reintroduced into the ecosystem” (US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior 1995). The report also noted that managers should have the ability to choose from a spectrum of management options, from full suppression to allowing naturally ignited fires to burn. With a degree of prescience, the report also emphasized the importance of the WUI. WUI areas would prove to be highly critical to wildland fire management in the subsequent years.

Throughout the 2000s, fire received national attention nearly every year (fig. 5.1). The decade began with a prescribed fire that escaped containment in Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico (ignited May 4, 2000). The resulting fire, known as the Cerro Grande Fire, covered 48,000 acres, threatened the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and burned 255 structures, mostly in the community of Los Alamos. This wildfire prompted substantial attention to the practice and potential consequences of management-ignited prescribed fire, ultimately prompting another review of wildfire management. This review provided continued support for the dual approach to wildfire management and resulted in additional clarification regarding management use of fire. Overall, the use of prescribed fires continued at a fairly consistent rate despite concerns among fire managers regarding the risks associated with fire use (National Interagency Coordination Center 2018).

Beyond the Cerro Grande Fire, the year 2000 saw a substantial increase in wildfire activity in the United States. Overall, just under 7.4 million acres burned, a 122% increase from the ten-year average of acres burned in the 1990s and the highest annual total since the 1950s, while suppression costs exceeded $1 billion for the first time. In many ways the 2000 wildfire season appears to be an inflection point that signaled entry into a different era of wildfire activity. While there is substantial interannual variation, total acres burned by wildfire trended higher beginning in 2000 (see fig. 5.1). Moreover, the number of large-scale fires also began to increase; of the 198 wildfires larger than 100,000 acres recorded since 1997 (when consistent records are available), 189 (95%) occurred in 2000 or later (National Interagency Fire Center 2019c). The impacts of this increased fire activity were particularly felt in the WUI; more than 9,000 structures were lost to wildfires between 2002 and 2004. Perhaps not surprisingly, suppression costs have also generally increased since the turn of the century, with average annual suppression costs increasing from $453,498,600 in the 1990s to $1.3 billion in the 2000s (National Interagency Fire Center 2019a).

In response to these fire impacts, a number of federal initiatives (e.g., the National Fire Plan, Ten Year Comprehensive Strategy, and Healthy Forests Restoration Act, or HFRA) focused on fire and fuel management. Two main themes run through these initiatives. First, they emphasize the use of fuel treatments, such as prescribed fire and mechanized thinning, to reduce the likelihood of fire particularly near communities. Second, these policies recognize that the wildland fire issue is too extensive to be managed by resource agencies alone and call for an unprecedented degree of collaboration with a broad array of stakeholders, including citizens in forest communities. As part of these initiatives, an effort was also made to identify those communities near federal lands that were most at risk to wildfire as a way to prioritize those areas most in need of attention. The resulting list included 11,376 communities across the United States. At that time, 9,600 communities were found to have no ongoing efforts to reduce hazardous fuels within or adjacent to their communities. To address this challenge, the HFRA encouraged the development of Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs) with the intention of bringing together the diverse range of local-level stakeholders to identify areas with the greatest risk of fire and preferred risk-reduction strategies. Thousands of CWPPs have been developed across the western United States, contributing to increased awareness of local wildfire risk and in many cases supporting efforts to reduce the likelihood of fire near homes (by engaging residents in efforts to remove fuels and make other changes to reduce their fire risk) and targeting implementation of fuels reduction efforts on nearby public lands (largely through the use of prescribed fire and mechanized thinning to remove vegetation).

A review of the social science research related to wildfire management completed near the end of the 2000s found high levels of understanding of the threat posed by wildfire to forest communities, adoption of some efforts to reduce the risk of fire on private property, and strong support for the use of mechanical methods and manager-ignited prescribed fire to reduce fuels (Toman et al. 2013). Indeed, across studies in multiple locations, 80% of study participants indicated support for some use of these practices. Generally, participants were willing to give managers greater discretion to use thinning than prescribed fire treatments. Limited research has examined acceptance of managing naturally ignited fires to achieve desired outcomes (the approach taken with the Yellowstone fires); however, the available findings suggest lower acceptance of this practice (ranging from 33% to 60% depending on the specific scenario) likely owing to perceived risks of escaped fires and subsequent negative outcomes (Kneeshaw et al. 2004; Winter 2002).

As the 2000s came to a close, resource management agencies completed another review of federal wildfire policy. While reaffirming the dual approach to wildfire management (suppression and fire use, depending on conditions and resource management goals), the review noted that even with the emphasis on the WUI in their previous review, the challenge of managing wildfires in the WUI had proven to pose a more complex challenge than previously expected (US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior 2009). In response, they called for greater coordination across federal, state, and local jurisdictions to manage conditions within the WUI.

Since 2010, wildland policy has continued with a focus on prefire efforts to reduce the risk of catastrophic fires; suppression of wildfires when they are deemed to pose a threat to life, property, or specified resource conditions; and use of fire in carefully determined conditions. Substantial effort has been undertaken to make further progress with efforts to prepare communities for fire while also developing tools to better support fire managers’ ability to sort through information and make decisions aligned with their identified goals during a fire event. Despite these substantial investments, the average number of acres burned and suppression costs (topping $3 billion for the first time in fiscal year 2018) have continued to increase.

Where Do We Go from Here? Wildfire Policy in a Climate-Changed World

Unfortunately, there is no simple solution to today’s wildland fire situation. Current conditions on the ground reflect the influence of several decisions made across multiple levels over the past century or more. While long-running efforts to suppress fires are often correctly implicated in raising current wildfire risks, several less obviously connected decisions—such as zoning and development, and our inability to meaningfully reduce greenhouse gas emissions—have also substantially contributed to current conditions and the associated wildfire risks. Thus addressing current wildfire risks will require more than the incremental steps seen over the last fifty years to slowly shift away from a strict fire suppression policy in limited situations, efforts to build awareness and support for fire and fuel reduction activities among local residents, or advances in coordination across jurisdictions involved in fuels reduction and fire suppression activities. While important, as the outcomes of recent years have indicated, efforts undertaken to date have proven insufficient to substantially address the current wildfire situation. To be clear, this is not meant as a slight against natural resource management agencies with responsibility for developing and implementing wildland fire policy (such as the US Forest Service, National Park Service, and Bureau of Land Management). Rather, the reality is that many of the factors contributing to today’s wildland fire management situation are outside the jurisdiction of these agencies.

Despite the state policy shifts to allow some naturally ignited fires to burn, in practice, fire suppression has continued as the dominant management approach. Although more recent data are difficult to come by, between 1999 and 2008, an average of 0.4% of wildland fires were allowed to burn to achieve desired outcomes on 204,000 acres (just under 3% of annual average of acres burned; data from National Interagency Fire Center 2019d). This emphasis on suppression is likely influenced in part by the culture developed within the agencies over time, where suppression is viewed as the default alternative viewed as safer and less “wasteful” of valuable resources. Such inclinations are likely further encouraged by the wildland fire management decision environment, as recent research suggests that systematic factors strongly incentivize engaging in aggressive efforts to suppress fires even when such actions may not align directly with managers’ stated objectives (Calkin et al. 2015).

At the local level, decisions are constrained by the need to comply with other related laws that are often more narrowly focused on a particular resource. Stephens et al. (2016) argue that such constraints may lead to “tunnel vision,” with management decisions focused on particular resource issues while potentially missing other important system-level changes that may have long-standing impacts beyond the particular resource of concern. For example, restricting the use of fire to protect current habitat for an endangered species in the near term may result in unintended, negative changes to the habitat over the long term owing to changing species and potentially an increased likelihood of a catastrophic fire and resulting loss of habitat.

One particularly perverse consequence of the current situation is the effect that increased suppression costs have had on the ability of the forest agencies to accomplish other management objectives. Over the last several years, an increasing portion of the annual budget for the US Forest Service has gone toward fire suppression costs, while 16% of the agency budget went to fire in 1995; in 2017, more than half of the agency’s budget was used for wildfire management activities (Kutz 2018). These increasing costs resulted in reallocating money originally slated for other purposes to cover fire suppression costs, potentially resulting in the unintended consequence of increasing the likelihood of wildfire in the future by shifting money away from projects aimed at restoring forest conditions and reducing fuel levels. Thankfully, this problem may have been alleviated through the federal budget passed by Congress in 2018 that set up an emergency fund from which the Forest Service can draw, beginning with the 2020 federal budget when suppression costs exceed their allocated fire suppression budget. The legacy of missed opportunities and backlog of uncompleted projects from past years will take several years to work through, however.

Even if the US Forest Service and other federal agencies are able to find success restoring forest conditions in a way that is amenable to fire playing a more natural role, there are several factors that influence the state of wildland fires that are outside the control of natural resource managers. From land-use development to climate change, a broad range of seemingly disparate factors, each with their own policy arena, affect the occurrence and impacts of wildland fires. Natural resource agencies have limited ability to affect all but a limited set of these factors.

With that in mind, the question remains, How can wildland fire policy be adapted to successfully navigate the challenges posed by this new era of wildfires? Not surprisingly, given the complexity of the situation and the years it has taken to arrive at current conditions, there are no quick or easy answers to this question. That said, the first step in adapting to today’s reality is to recognize that wildland fires are going to occur on the landscape, likely more frequently than they have in the past. While there has been an increasing recognition of the role of fire within forested ecosystems over the past century, there has still generally been at least an implicit expectation that fires could be controlled before causing substantial harm to forest communities. The experiences of the last few fire seasons have shattered those illusions. Ultimately, a policy of fire exclusion is simply not feasible, and attempting to pursue such an approach may contribute to a false sense of security among politicians and communities and slow down any efforts to make meaningful changes on the harder questions influencing wildfires and their resulting impacts.

Given these starting conditions, discussions of wildland fire policy should shift to consider how to adapt ecological and human systems to be more resilient in the face of wildland fires. From an ecological perspective, others have argued for the need to substantially transition management to emphasize restoration of ecological conditions and processes (e.g., Stephens et al. 2016). Ecological restoration, defined as “the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed” (Society for Ecological Restoration 2004), has substantial promise to provide a framework to think about wildfire within a broader context and over longer timescales than the typical approach that largely emphasizes short-term risks to a narrow set of resources (Stephens et al. 2016). Moreover, recent research suggests that using an ecological restoration framework can encourage stakeholders, who may have different preferences for forest management priorities, to focus on more abstract values where they are more likely to find common ground to overcome the conflict that has long characterized forest management decisions (Toman et al. 2019).

The concept of resilience can also provide a useful framework for considering the necessary adaptation within forest communities required by a changing climate. Beginning with resilience as the desired state, these communities can reframe the discussion from one that holds fire exclusion as the default to recognizing the reality of conditions on the ground and providing incentive to engage in proactive preparation for the occurrence of wildland fire and develop plans and mechanisms for how to shape resulting effects and recover when a fire does occur (Abrams et al. 2015). Moreover, such an approach could engender a broader conversation about the range of factors that contribute to successful communities, with benefits likely to accrue to thinking about not only wildland fire but also other adverse events. A developing body of research examining community resilience identifies the importance of recognizing the distinct character of different communities within their surrounding ecological and social context while illustrating potential pathways to develop increased resilience (Paveglio et al. 2018).

These are much more complicated questions than those typically addressed by existing wildland fire policy. While natural resource agencies have made admirable efforts to move ahead with restoration efforts and encourage community preparation efforts, the success of these efforts has been mixed across the landscape. The conditions that influence the occurrence and impacts of wildland fire exceed the jurisdiction of any one agency or organization to address. As a multijurisdictional and multiscale issue, it is unclear who is positioned to provide leadership to consider fire within the broader, complex system within which fires function. But without consideration of the multiple variables that influence whether wildland fires occur, their behavior following ignition, and the resulting impacts, we will not be able to address the full scope of the current challenge and will generally find ourselves playing catch-up and reacting as conditions on the ground change. The most common recommendations for fire policy moving forward typically involve calls for more acres treated through application of fire and mechanical means to reduce fuels that may burn in unplanned ignitions (e.g., Vose et al. 2018). While such recommendations are logical, as they address some aspects of the current problem (increasing fuel loads, particularly around communities) and generally fall within the scope of federal natural resource agencies, they will likely be inadequate to effectively address the current wildland fire dilemma. Even a more radical shift from the status quo to establish resilience as the guiding concept for resource management (as suggested by Stephens et al. 2016) will only address limited aspects of the fire dilemma. Unless these efforts include some opportunity and authority to consider relevant topics at a higher level, they will likely exclude key questions that influence future fire outcomes, including WUI development and community preparation (typically considered at local or regional level). Moreover, such an approach would still be limited to addressing issues within the purview of the agencies and would be largely silent on agreements regarding climate change mitigation (typically considered at regional to global levels with negotiating power closely held by appropriate executive officer) and thus would have modest ability to address one of the key drivers of ongoing wildfire trends.

Conclusion

Forested systems across the western United States have experienced substantial ecological change over the past century as a result of fire and forest management actions. Such changes are currently compounded by ongoing climate change and have resulted in a shift in wildfire activity with increasing frequency of and impacts from wildfire events. Combining these changes with increased development within the WUI has resulted in a substantial number of communities at risk to wildfire.

An effective response to this current situation requires more than the incremental approach to adapting wildland fire policy than has been evident up to this point. Such a shift requires a changed approach to considering wildland fire across multiple scales. At the national level, it seems critical to move away from treating wildland fires as unexpected disruptions occurring in isolation from other management initiatives that merit an immediate, emergency response every fire season. By focusing on the short-term impacts of fire, this approach sets up a juxtaposition where wildfire will likely be viewed as being in conflict with other ecological objectives in need of control and, ironically, may contribute to increased risk of fire in the future by shifting resources from efforts to restore ecological conditions to increase the resilience of forest systems to wildfire events. Rather, wildland fire should be viewed as a core ecological process that provides critical functions to ecological systems that will likely be increasingly linked with the success and well-being of WUI communities.

Such efforts can contribute to meaningful improvements on the ground and, hopefully, buy time for agreement to be reached at a greater level on productive actions to address climate change. The challenge is daunting. Effectively addressing climate change will require coordination from global to local levels, including governments, organizations, and citizens living in widely different circumstances, holding different perspectives, and being driven to achieve different goals (Maibach et al. 2009).

Progress on these larger issues will be slow going. In the meantime, wildland fire policy and management will be best served to emphasize resilience in the new era of wildfire.

References

Abrams, Jesse B., Melanie Knapp, Travis B. Paveglio, Autumn Ellison, Cassandra Moseley, Max Nielsen-Pincus, and Matthew S. Carroll. 2015. “Re-Envisioning Community-Wildfire Relations in the U.S. West as Adaptive Governance.” Ecology and Society 20(3): 34. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-07848-200334. (↵ Return)

Agee, Jim K. 1993. Fire Ecology of Pacific Northwest Forests. Washington, DC: Island Press. (↵ Return)

Agee, Jim K. 1997. “Fire Management for the 21st Century.” In Creating a Forestry for the 21st Century, edited by K. A. Kohm and J. F. Franklin, 191–202. Washington, DC: Island Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Ager, Alan A., Michelle A. Day, Charles W. McHugh, Karen Short, Julie Gilbertson-Day, Mark A. Finney, and David E. Calkin. 2014. “Wildfire Exposure and Fuel Management on Western US National Forests.” Journal of Environmental Management 145: 54–70. (↵ Return)

Arno, Stephen F., and James K. Brown. 1991. Overcoming the Paradox in Managing Wildland Fire in Western Wildlands. 40–46. Missoula: Montana Forest and Conservation Experiment Station, University of Montana. (↵ Return)

Bond, William J., Ian Woodward, and Guy F. Midgley. 2005. “The Global Distribution of Ecosystems in a World without Fire.” New Phytologist 165(2): 525–38. (↵ Return)

Busenberg, George. 2004. “Wildfire Management in the United States: The Evolution of a Policy Failure.” Review of Policy Research 21(1): 145–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2004.00066.x. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6)

CalFire. 2019. “Camp Fire.” Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2018/11/8/camp-fire/. (↵ Return)

Calkin, David C., Mark A. Finney, Alan A. Ager, Matthew P. Thompson, and Krista M. Gebert. 2011. “Progress towards and Barriers to Implementation of a Risk Framework for US Federal Wildland Fire Policy and Decision Making.” Forest Policy and Economics 13: 378–89. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Calkin, David E., Krtist M. Gebert, J. Greg Jones, and Ronald P. Neilson. 2005. “Forest Service Large Fire Area Burned and Suppression Expenditure Trends, 1970–2002.” Journal of Forestry 103(4): 179–83. (↵ Return)

Calkin, David E., Matthew P. Thompson, and Mark A. Finney. 2015. “Negative Consequences of Positive Feedbacks in US Wildfire Management.” Forest Ecosystems 2:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-015-0033-8. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Callicott, J. Baird. 1994. “A Brief History of American Conservation Philosophy.” In Sustainable Ecological Systems: Implementing an Ecological Approach to Land Management, 10–14. General Technical Report RM-247. Fort Collins, CO: US Forest Service. (↵ Return)

Dennison, Phillip E., Simon C. Brewer, James D. Arnold, and Max A. Moritz. 2014. “Large Wildfire Trends in the Western United States, 1984–2011.” Geophysical Research Letters 41(8): 2928–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059576. (↵ Return)

Dombeck, Michael P., Jack E. Williams, and Christopher A. Wood. 2004. “Wildfire Policy and Public Lands: Integrating Scientific Understanding with Social Concerns across Landscapes.” Conservation Biology 18: 883–89. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Donovan, Geoffrey H., Jeffrey P. Prestemon, and Krista Gebert. 2011. “The Effect of Newspaper Coverage and Political Pressure on Wild Fire Suppression Costs.” Society and Natural Resources 24: 785–98. (↵ Return)

Egan, Timothy. 2009. The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Federal Register. 2001. “Urban Wildland Interface Communities within Vicinity of Federal Lands That Are at High Risk from Wildfire.” Federal Register 66: 751–77. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2001/01/04/01-52/urban-wildland-interface-communities-within-the-vicinity-of-federal-lands-that-are-at-high-risk-from. (↵ Return)

Fitch, Ryan A., Yeon S. Kim, Amy E. M. Waltz, and Joe E. Crouse. 2017. “Changes in Potential Wildland Fire Suppression Costs Due to Restoration Treatments in Northern Arizona Ponderosa Pine Forests.” Forest Policy and Economics 87: 101–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.11.006. (↵ Return)

Gergel, Diana R., Bart Nijssen, John T. Abatzoglou, Dennis P. Lettenmaier, and Matt R. Stumbaugh. 2017. “Effects of Climate Change on Snowpack and Fire Potential in the Western USA.” Climatic Change 141(2): 287–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1899-y. (↵ Return)

Hawbaker, Todd J., and Zhiliang Zhu. 2012. “Projected Future Wildland Fires and Emissions for the Western United States.” In Baseline and Projected Future Carbon Storage and Greenhouse-Gas Fluxes in Ecosystems of the Western United States, edited by Zhiliang Zhu and Bradley C. Reed, 1–12. Reston, VA: US Geological Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1797/pdf/pp1797_Chapter8.pdf. (↵ Return)

Hays, Samuel P. 1999. Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890–1920. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. (↵ Return)

Hough, F. B. 1882. Report on Forestry. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. (↵ Return)

Kneeshaw, Katie, Jerry J. Vaske, Alan D. Bright, and James D. Absher. 2004. “Situational Influences of Acceptable Wildland Fire Management Actions.” Society & Natural Resources 17(6): 477–89. (↵ Return)

Kutz, Jessica. 2018. “Fire Funding Fix Comes with Environmental Rollbacks.” High Country News, March 29, 2018. https://www.hcn.org/articles/wildfire-fire-funding-fix-includes-environmental-rollbacks. (↵ Return)

Litschert, Sandra E., Thomas C. Brown, and David M. Theobald. 2012. “Historic and Future Extent of Wildfires in the Southern Rockies Ecoregion, USA.” Forest Ecology and Management 269: 124–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2011.12.024. (↵ Return)

Littell, Jeremy S., David L. Peterson, Karin L. Riley, Yongqiang Liu, and Charlie H. Luce. 2016. “A Review of the Relationships between Drought and Forest Fire in the United States.” Global Change Biology 22(7): 2353–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13275. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Löw, Petra. 2019. “The Natural Disasters of 2018 in Figures.” Munich RE. August 1, 2019. https://www.munichre.com/topics-online/en/climate-change-and-natural-disasters/natural-disasters/the-natural-disasters-of-2018-in-figures.html. (↵ Return)

Maguire Lynn A., and Elizabeth A. Albright. 2005. “Can Behavioral Decision Theory Explain Risk-Averse Fire Management Decisions?” Forest Ecology and Management 211(1): 47–58. (↵ Return)

Maibach, Edward, Connie Roser-Renouf, and Anthony Leiserowitz. 2009. Global Warming’s Six Americas: An Audience Segmentation Analysis. New Haven, CT: Yale Project on Climate Change, George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication. (↵ Return)

Marlon, Jennifer R., et al. 2012. “Long-Term Perspective on Wildfires in the Western USA.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(9): E535–E543. (↵ Return)

NICC. 2018. Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report 2017. Boise, ID: National Interagency Coordination Center. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4)

NICC. 2019. Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report 2018. Boise, ID: National Interagency Coordination Center. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4)

NIFC. 2019a. "Suppression Costs (1985–2018).” Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_documents/SuppCosts.pdf. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

NIFC. 2019b. “Total Wildland Fires and Acres (1926–2017).” Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_stats_totalFires.html. (↵ Return)

NIFC. 2019c. “Wildfires Larger Than 100,000 Acres (1997–2018).” Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_stats_lgFires.html. (↵ Return)

NIFC. 2019d. “Wildland Fire Use Fires and Acres by Agency.” Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_stats_fireUse.html. (↵ Return)

NWCG. 2019. “Glossary.” Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.nwcg.gov/about-the-nwcg-glossary-of-wildland-fire. (↵ Return)

Paveglio, Travis B., Matthew S. Carroll, Amanda M. Staseiwicz, Daniel R. Williams, and Dennis R. Becker. 2018. “Incorporating Social Diversity into Wildfire Management: Proposing ‘Pathways’ for Fire Adaptation.” Forest Science 64(5): 515–32. (↵ Return)

Pyne, Stephen J. 1997. Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire. Seattle: University of Washington Press. (↵ Return)

Pyne, Stephen J. 2001. Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910. New York: Viking Penguin. (↵ Return)

Radeloff, Volker C., Miranda H. Mockrin, and David P. Helmers. 2018. “Mapping Change in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) 1990–2010: State Summary Statistics. University of Wisconsin-Madison." http://silvis.forest.wisc.edu/data/wui-change. (↵ Return)

Radeloff, Volker C., et al. 2018b. “Rapid Growth of the US Wildland-Urban Interface Raises Wildfire Risk.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (13): 3314–19. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718850115. (↵ Return)

Rothman, Hal K. 2007. Blazing Heritage: A History of Wildland Fire in the National Parks. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Schoennagel, Tania, et al. 2017. “Adapt to More Wildfire in Western North American Forests as Climate Changes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114: 4582–90. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Smith, Diane M. 2017. Sustainability and Wildland Fire: The Origins of Forest Service Wildland Fire Research. FS-1085. Missoula, MT: US Forest Service. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Society for Ecological Restoration. 2004. The SER International Primer on Ecological Restoration, Version 2. Washington, DC: Society for Ecological Restoration International Science and Policy Working Group. (↵ Return)

Stephens, Scott L., Brandon M. Collins, Eric Biber, and Peter Z. Fulé. 2016. “U.S. Federal Fire and Forest Policy: Emphasizing Resilience in Dry Forests.” Ecosphere 7 (9): 1–19. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6) (↵ Return 7) (↵ Return 8)

Stephens, Scott L., Brandon M. Collins, Christopher J. Fettig, Mark A. Finney, Chad M. Hoffman, Eric E. Knapp, Malcolm P. North, et al. Wayman. 2018. “Drought, Tree Mortality, and Wildfire in Forests Adapted to Frequent Fire.” BioScience 68(2): 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix146. (↵ Return)

Thompson, Matthew P. 2014. “Social, Institutional, and Psychological Factors Affecting Wildfire Incident Decision Making.” Society and Natural Resources 27 (6): 636–44. (↵ Return)

Thompson, Matthew P., Donald G. MacGregor, Christopher J. Dunn, David E. Calkin, and John Phipps. 2018. “Rethinking the Wildland Fire Management System.” Journal of Forestry 116(4): 382-390. (↵ Return)

Toman, Eric, Melanie Stidham, Sarah McCaffrey, and Bruce Shindler. 2013. Social Science at the Wildland-Urban Interface: A Compendium of Research Results to Create Fire-Adapted Communities. 75 pp. General Technical Report NRS-111. Newtown Square, PA: Forest Service, Northern Research Station. https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/43435. (↵ Return)

Toman, Eric, Emily H. Walpole, and Alexander Heeren. 2019. “From Conflict to Shared Visions: Science, Learning, and Developing Common Ground.” In A New Era for Collaborative Forest Management: Policy and Practice Insights from the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program, edited by W. H. Butler and C. Schultz, 103–18. Milton Park: Routledge. (↵ Return)

US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior. 1995. Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy and Program Review. Final Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior. https://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/documents/strategy/foundational/1995_fed_wildland_fire_policy_program_report.pdf. (↵ Return)

US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior. 2009. Guidance for Implementation of Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture and US Department of the Interior. https://www.nifc.gov/policies/policies_documents/GIFWFMP.pdf. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

US Department of the Interior, Office of Wildland Fire. 2019. "Governance." January 18, 2017. https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/chapter_2_responsibilities_and_governance.pdf. (↵ Return)

USDA Forest Service. n.d. The Great Fire of 1910. Washington, DC: US Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5444731.pdf. (↵ Return)

van Wagtendonk, Jan W. 2007. “The History and Evolution of Wildland Fire Use.” Fire Ecology 3 (2): 3–17. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6) (↵ Return 7) (↵ Return 8)

Vose, James M., David L. Peterson, Grant M. Domke, Christopher J. Fettig, Linda A. Joyce, Robert E. Keane, Charles H. Luce, et al. 2018. “Forests.” In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Vol. 2, edited by D. R. Reidmiller et. al., 232–67. Washington, DC: US Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH6. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5)

Westerling, Anthony L. 2016. “Increasing Western US Forest Wildfire Activity: Sensitivity to Changes in the Timing of Spring.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371: 20150178. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0178.

Westerling, Anthony L., Hugo G. Hidalgo, Daniel R. Cayan, and Thomas W. Swetnam. 2006. “Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity.” Science 313 (5789): 940–43. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Whitlock, Cathy, Jennifer R. Marlon, Christy Briles, Andrea Brunelle, Colin J. Long, and Patrick Bartlein. 2008. “Long-Term Relations among Fire, Fuel, and Climate in the N-W US Based on Lake-Sediment Studies.” International Journal of Wildland Fire 17(1): 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07025. (↵ Return)

Williams, Michael. 1989. Americans and Their Forests: A Historical Geography. 599 pp. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return)

Wilson, Robyn S., Patricia L. Winter, Lynn A. Maguire, and Timothy Ascher. 2011. “Managing Wildfire Events: Risk-Based Decision Making among a Group of Federal Fire Managers.” Risk Analysis 31: 805–18. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Winter, Patricia L. 2002. “Californians’ Opinions on the Management of Wildland and Wilderness Fires.” In Homeowners, Communities, and Wildfire: Science Findings from the National Fire Plan, edited by Pamela Jakes, 84–92. Washington, DC: US Forest Service. (↵ Return)