Implications of Tribal Sovereignty, Federal Trust Responsibility, and Congressional Plenary Authority for Native American Lands Management

Shane Day

Introduction

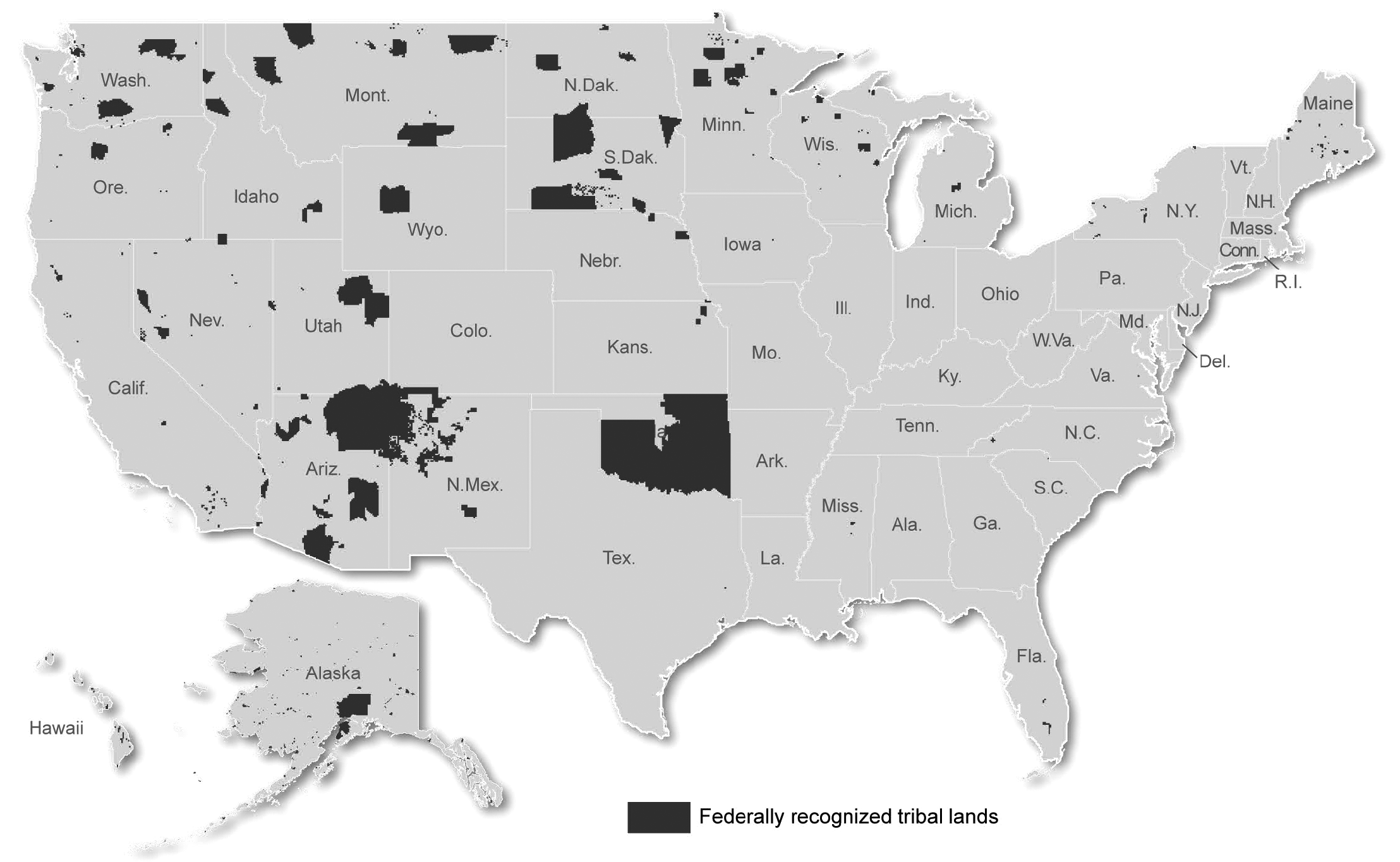

Many Americans express surprise when they discover that Native American reservation lands are not technically owned by the tribes themselves but are instead owned by the federal government and held in trust for the benefit of the tribes. Furthermore, specific tracts of lands within reservation boundaries have been converted to individual ownership, such that most reservations exhibit a complex matrix of property rights distributed among the federal government, tribal governments, individual Native Americans, and nontribal individuals. While some general patterns can be identified, for the most part, each of the 573 federally recognized tribal governments in the United States has had a unique historical relationship with the US federal government, with land ownership and land management responsibilities varying considerably from tribe to tribe owing to the vicissitudes of official government policies toward individual tribes (fig. 14.1). In order to grasp the multitude of contemporary Native American land management policy issues, one must understand the history of US federal policy toward tribes, the structural characteristics that explain why policy has been so inconsistent and ad hoc in implementation, and how individual tribes have been affected differentially by various federal policies on land management issues.

This chapter briefly outlines federal Indian policy with a focus on major developments that affect land ownership and management in the contiguous United States. The chapter highlights various political conditions and policy developments, including the condition of inherent tribal sovereignty, the federal trust responsibility toward tribes, reserved treaty rights, congressional plenary authority, different pathways to federal recognition, and the rise of self-governance authority, each of which has shaped the specific kinds of land management activities undertaken by tribal governments. Several emergent issue areas are then highlighted as a means of illustrating the diverse range of land management issues facing tribes, including devolved tribal land management of reservation resources, comanagement authority of off-reservation federal lands, consultative authority regarding land-use planning on private lands, and relocation initiatives as an adaptation strategy for negative impacts of climate change. It concludes with the assertion that while many Native American tribes have dramatically expanded the scope of their land management responsibilities, others have not, as a result of either being unwilling to do so or not enjoying the same set of opportunities as enjoyed by other tribes, owing to their specific relationship with the federal government. It is thus impossible to generalize about tribal land management activity across all tribal governments. Regardless, the tenuous position of Native Americans vis-à-vis the federal government always casts a shadow over the specific range of governance activities carried out by tribal governments, with the status quo involving any particular tribe being potentially overturned at any moment by a fundamental change in federal policy.

History of Tribal-Federal Relations

The relationship between Native Americans and European settlers during the colonial era can best be characterized as a “nation-to-nation relationship” in which the English negotiated treaties with tribes as co-sovereign entities, even as the English disparaged their “savage” cultural practices and “primitive” forms of political organization (Wilkins and Stark 2011, pp. 52-53). These treaties largely served to attain land cessions in areas that were attractive to English settlers, in exchange for reserved areas that were fully under the control of the tribes themselves. These treaties were often negotiated to end periods of open hostilities between colonists and tribes, and thus frequently reflected asymmetrical bargaining positions between the vanquishers and the vanquished, although some treaties were struck against a backdrop of peaceful relations that the signatories hoped to codify and perpetuate into the future. Upon independence, the US government continued this practice, implicitly recognizing the inherent sovereignty of indigenous nations. But the substance of the treaties negotiated by the US government increasingly began to shift toward land cession in exchange for monetary concessions and direct provision of services by the federal government over such things as health care and education, which opened the door for subsequent interventions in tribal affairs.

As the balance of power between Native Americans and colonial settlers began to tilt toward the latter, treaties were increasingly used by tribes to get what concessions they could get while avoiding the perceived inevitability of armed conflict. For instance, tribes in the Pacific Northwest for the most part avoided armed conflict at the cost of land cessions, but while preserving treaty-codified rights to culturally significant resources and practices such as whaling, shellfish harvesting, and fishing (Bernholz and Weiner 2008; Richards 2005). The tilt in the balance of power also led to the federal government’s chipping away at principles of tribal sovereignty and, ultimately, to the ending of the practice of treaty-making altogether by 1871 (Pevar 2012, p. 94). After 1871, several reservations were established through the use of executive orders, but Congress ended this practice in 1919, such that today, only Congress can create a reservation (Pevar 2012, p. 95).

Several Supreme Court cases set the stage for this diminishment of tribal sovereignty. The question of land title was addressed in Johnson v. M’Intosh,1 which established that the US government acquired ownership of all lands by virtue of discovery and conquest, but Indians retained possessory title, although not outright ownership, to the land (Pevar 2012, pp. 24-25). Among other things, this forbids the sale of Indian lands without the authorization of the secretary of the interior, who serves as the primary federal agent in carrying out congressional policy toward tribes. The so-called Cherokee Cases, especially Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia,2 furthermore established that while tribes were sovereign entities, and thus not subject to the jurisdiction of state governments, they were nonetheless “dependent nations” whose relationship with the United States was akin to that “of a ward to his guardian.” This judgment was foundational to the emergence of the doctrine of trust responsibility, in which the federal government has both power over Indians and responsibility toward them, particularly in carrying out the specific promises enshrined in treaties. Trust responsibility furthermore implies that a treaty holds the same weight as a federal law; that is, it is the “highest law of the land” (Duthu 2008). In the case of Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, however, the court held that Congress possesses “plenary,” or complete and unshared, authority over tribes under the logic of the Commerce Clause of the Constitution.3 Thus, while treaties and federal laws are theoretically equal, Congress has the right to unilaterally abrogate the terms of a treaty, albeit subject to the provisions of the Due Process and Just Compensation Clauses (Duthu 2008; Pevar 2012). As a result, tribes have a vulnerable relationship with the federal government. While the government has a set of recognized obligations toward tribes, it can effectively terminate the relationship with any given tribe, along with all of its obligations toward it, with a simple act of Congress. Arguably, the only thing that impedes Congress from completely doing away with tribes is the pressure of public opinion.

The inconsistent pattern of federal policy toward tribes can be seen as reflecting the changing tides of public opinion. Subsequent outrage in the state of Georgia in the wake of the Cherokee Cases, and President Andrew Jackson’s refusal to uphold the Supreme Court’s judgement in Worcester v. Georgia, led to the policy of “Indian removal,” in which several tribes were forcibly removed to present-day Oklahoma, which was originally designated as a self-governing “Indian Territory.” Outside of Indian Territory, reservations were used to distribute promised goods and services, while maintaining a “safe” degree of separation between tribal and settler communities. Implementation, however, was heavily concentrated in the hands of a respective Indian Agent, which, owing to the relative lack of oversight and control on the frontier, could often run reservations as personal fiefdoms (Wilkins and Stark 2011). After the Civil War, the government followed a general policy of “assimilation,” in which individual Indians were either encouraged or forced to adopt western customs. Perhaps the most disruptive policy of this area was established by the General Allotment Act of 1887, which sought to break up the reservation system, assimilate Indians into the private property rights system, and encourage economic development by making individual Indians commercial farmers (Royster 1995). Toward this end, allotment typically entailed dividing up communally held reservation lands into 160-acre parcels that were then given to each tribal member, who after a twenty-five-year period could sell the deed to the property (Royster 1995). Furthermore, once all 160-acre properties were distributed, any “surplus land” was sold off to non-Indians. Individual allotments that were not sold off were frequently subdivided as a result of inheritance, such that the promise of economic development through agriculture rarely materialized, as each subsequent generation had less and less land with which to farm (Royster 1995).

In response to publicized abuses by Indian agents, controversy over the condition of boarding schools, and the failure of allotment, the Progressive movement picked up the cause of Indian rights and initiated a dramatic shift in federal Indian policy. In 1934, the federal government repealed allotment and encouraged the development of tribal governments through the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). Although the IRA period maintained certain assimilationist policies, paternalistically restricted the range of government types and functions available to tribes, and perpetuated the power and high degree of delegated discretion of the secretary of interior, it nevertheless represented the most favorable political position of tribes since US independence (Pevar 2012). In terms of land issues, while the damage from allotment had already been done, such that by 1834 less than one-third of tribal lands that had existed pre-allotment remained in tribal hands, by 1953, tribes in aggregate increased their landholdings by more than two million acres (Pevar 2012, p. 11).

This more positive orientation toward tribes ended in 1953, however, as new fiscal priorities in the wake of World War II led the federal government to roll back its fiduciary responsibilities to tribes. During these “Barren Years”—also known as the “Termination Era”—the federal government, acting under congressional plenary authority, terminated the recognition of more than a hundred tribal governments, devolved federal criminal and civil jurisdiction to certain state governments under Public Law 280, and officially encouraged the migration of individual Indians to urban areas to obtain better employment opportunities (Deloria and Lytle 1984). An unforeseen consequence of the latter was the emergence of a pan-Indian ethnic identity and social movement that reacted against these new attacks on tribal sovereignty. The resulting Indian rights movement was largely coterminous with the broader civil rights movement of the 1960s and helped to usher in a sea change in popular opinion toward Native American causes.

As a result of Indian activism, the official policy of Congress since the late 1960s has been the promotion of tribal sovereignty and self-determination. While the specific definition of self-determination is somewhat ambiguous and contested among indigenous peoples, at a minimum it refers to “the right to participate in the democratic process of governance and to influence one’s future—politically, socially and culturally” (Wessendorf 2011). To this end, tribes have been granted greater discretion to develop their own government forms with less fear of intervention by the secretary of interior through the use of their de facto veto authority, attained the power to operate gaming operations, won court cases upholding various treaty provisions that had been under attack by state and federal governments, gained jurisdiction over child custody cases, and have seen a general expansion in the range of governmental services they provide (see generally Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development 2008; Pevar 2012; Wilkins and Stark 2011). Additionally, many formerly terminated tribes have reattained federal recognition, albeit without a full restoration of their former land bases, and many tribes have gained formal recognition for the first time. From the end of the treaty-making era in 1871, the process of formal recognition has essentially come through three different pathways: an act of Congress, an administrative process through the Department of the Interior for petitioning tribes that meet seven different criteria, or a federal court order (Pevar 2012, pp. 271-274). The primary pathway is via administrative recognition; however, the process has been criticized as burdensome, cost-prohibitive, and time-consuming, leading many tribes to seek, with mixed success, congressional or judicial recognition (Pevar 2012, pp. 271-274). These latter two pathways, however, potentially expose tribes to a greater degree of restrictions on tribal government powers and access to particular federal programs. For instance, the Lumbee Act of 1956 merely recognized the existence of the Lumbee of North Carolina as “Indians” but denied them all of the benefits of full federal recognition (Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development 2008, p. 61), and almost half of the recognition bills introduced in Congress since 1975 have contained some form of restriction of tribal authority, most commonly in the form of granting criminal or civil jurisdiction over tribal lands to state governments, restricting gaming rights, or restricting tribal hunting and fishing (Carlson 2016). Furthermore, the political status of Alaskan Natives is distinct from tribes in the Lower 48, because the process of their federal recognition under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which conveyed full rights of land ownership to more than two hundred Native Village Corporations, are further agglomerated into thirteen Regional Corporations that collectively hold subsurface mineral rights (Pevar 2012, pp. 261-264). As a result, tribal authority and jurisdiction over their own lands vary considerably between tribes and are dependent upon whether a tribe has been recognized by treaty, administrative action, court order, or a specific act of Congress.

Perhaps the most significant modern development in tribal governance has been the gradual expansion of self-governance authority (for an overview of the history of self-governance policy, see Strommer and Osborne 2014). In 1975, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA), which provides a framework for tribes to negotiate contract agreements with federal agencies to take over implementation responsibility for programs that otherwise would be provided by the federal government, principally the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service, with funding coming from the federal government. In 1988, Congress approved the Indian Self-Governance Demonstration Project, in which participating tribes could essentially receive block grants covering multiple programs and services. This allowed tribes to redesign programs and allocate funding across program areas as they saw fit. In response to the success of this program, in 1994 and 2000, Congress amended the ISDEAA to effectively make self-governance authority permanent and available to any interested tribe. Although participation is optional, and more than half of all tribes choose to participate, many do not owing to a political perspective that the federal government has never lived up to its treaty obligations, that levels of available funding under the program are insufficient, and that by participating in self-governance, tribes are effectively releasing the federal government from its trust responsibilities (Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development 2008). These tribes essentially continue to rely upon the federal government for direct service provision, jurisdiction, and management authority. Tribes that do choose to contract and compact for direct implementation of government services have an enhanced position that can make them significant players in a variety of land management activities.

The Scope of Indian Lands and Jurisdiction

The term “Indian country” is used to designate all lands that have been set aside and designated primarily for use by Indians. Technically, it refers to all lands within a reservation, but the designation also extends to some lands outside of a reservation that are either owned by a tribe, owned by the federal government and used primarily for the benefit of Indians (such as housing projects, schools, health clinics, etc.), or restricted individual allotments of land owned by Indians that are no longer part of reservations that have been terminated by acts of Congress, as is the case for most federally recognized tribes in Oklahoma (Pevar 2012, pp. 20-23). The term is also used by many to refer to off-reservation areas where tribes enjoy special rights of way or usufruct rights, such as treaty fishing access sites along the Columbia River in Washington and Oregon (Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission 2020), or public lands such as various national parks or monuments to which they hold concurrent jurisdiction or comanagement authority, such as Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument in New Mexico (Pinel and Pecos 2012). As a matter of law, claims that these latter areas are Indian country are contestable, but while tribes’ primary land-use activities and jurisdiction lie within areas that conform to the legal definition of Indian country, their activities and policymaking authority frequently extend beyond that definition.

A further complication in delineating the scope of tribal land management authority is that even within reservation boundaries tribal jurisdiction is often fragmented. As a result of the various changes in federal Indian policy as outlined above, patterns of land ownership within a particular reservation are highly varied and often entail a complex patchwork of ownership and property rights. Most reservations consist of significant portions of “Indian trust land,” which is land that is technically owned and held in trust by the federal government with the explicit requirement that it be held for the collective and exclusive benefit of the tribe (Pevar 2012, pp. 94-95). As a result of this trust relationship, tribes cannot unilaterally dispense of or use these lands without approval by the federal government, thus representing a significant check on tribal authority. But those tribes that participate in self-governance authority often hold a de facto higher level of management authority over these lands, as such authority has effectively been devolved to them by the federal government as a function of self-governance (Clow and Sutton 2001). As a result of the policy of allotment, on many reservations, significant portions of formerly trust reservation lands were converted into fee-simple ownership held by individual tribal citizens. Over the years, many of these fee-simple tracts held by Indians were sold off to nontribal members, adding to the holdings that were sold off as “surplus” lands. As a result, any given reservation may consist of a complex mix of federal trust lands, fee-simple lands held by tribal members, and fee-simple lands held by nonmembers.

This situation entails significant jurisdictional issues. For trust lands, the federal government either manages these lands or devolves authority to the tribes themselves under the logic of self-governance policy. Federal decisions regarding land use and dispensation are theoretically constrained by the Due Process Clause, which stipulates that any decision made by Congress must be reasonable and nondiscriminatory; the Just Compensation Clause, which requires Congress to provide fair and adequate compensation for any taken property, including the value of all resources on it; and the doctrine of trust responsibility, which forces the government to manage lands in the best interests of and in government-to-government consultation with the tribes themselves (Pevar 2012, p. 76). Tribes have broad powers to regulate land-use activities occurring on fee-simple lands held by tribal members but significantly constrained authority over fee-simple holdings of non-Indians. In this latter instance, state governments have primary jurisdiction, although tribes have relatively broad zoning authority and may petition for regulatory jurisdiction when a nonmember’s action threatens the political integrity, economic security, or health or welfare of the tribe, although current precedent significantly limits this scope to “cases in which the tribe’s survival is threatened by non-member conduct” (Ford and Giles 2015, p. 538; Smith 2013).

In addition, certain land areas can be subject to a claim of “Indian title land.” Land that a tribe can claim to be a part of its ancestral homelands may potentially entail a right of continued occupancy if the federal government has never taken any formal action to terminate it (Pevar 2012, p. 25). Thus federal or even private lands outside of an established reservation, which have not been formally subjected to formal extinguishment by congressional action, may be subject to a possessory claim. This policy has generated a number of claims where federal lands have been abandoned and declared as surplus, such as in the occupation of Alcatraz from 1969 to 1971 (Fortunate Eagle 1992). For land that has passed into private ownership, however, tribes have faced significant obstacles in establishing title. Current precedent set in the Supreme Court case City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York,4 for instance, establishes a time limit on tribes in staking their possessory claims (Pevar 2012, p. 25).

Owing to the legacy of allotment and the overall complexity of land ownership and rights, tribes have an obvious interest in obtaining additional land or consolidating ownership of lands within reservation boundaries, and there are several ways that tribes have been successful in expanding their landholdings. Tribes often purchase fee-simple lands, and they may do so both off and on reservation. Such landholdings are subject to state taxation, however, whereas trust land is not (Pevar 2012, pp. 74-75). Therefore tribes have a financial incentive to hold most of their lands in trust. Most tribes can request that the secretary of interior convert, or “take into trust,” lands that have been purchased by the tribe, although there is ambiguity over which tribes are eligible to do so, as historically this has been interpreted to be limited to tribes that had been federally recognized by 1934, when the Indian Reorganization Act was enacted (Pevar 2012, pp. 74-75). Tribes that have gained federal recognition in the modern era are relatively more constrained in their ability to expand their land bases and are often forced to hold fee-simple lands that are subject to state taxation. Additionally, the federal government has established a process for the secretary of interior to purchase lands to be taken into trust on behalf of tribes, although Congress often does not appropriate sufficient funds for such purposes (Pevar 2012, pp. 74-75). The primary use of such programs has been to regain territory within reservations that was lost as a result of allotment, and off-reservation purchases are relatively rare. Furthermore, off-reservation purchases can be politically controversial, particularly in situations where such purchases are for the purpose of establishing gaming enterprises, and the Department of Interior is currently considering sweeping changes that will make future trust land acquisitions more difficult (Cummings 2017).

Tribal Land Management Activities

The particular mix of a particular tribe’s land management authority and activities is thus dependent upon several factors. Arguably the most important pertains to the specific process by which a tribe attained federal recognition. Those tribes that were recognized by treaty hold a relatively advantaged position owing to the status of treaties that are the “supreme law of the land” under Article VI of the Constitution, have been established for longer, and generally have larger reservation territories. “Treaty tribes” furthermore may hold unique reserved treaty rights that explicitly grant or otherwise imply greater authority over land management practices, even on nontribal lands off reservation. Tribes that have been recognized by executive order or via the Bureau of Indian Affairs administrative process essentially have a status similar to that of treaty tribes, although typically without any of the special reserved rights enjoyed by treaty tribes. Congressionally recognized tribes meanwhile typically enjoy all of the rights and responsibilities of federal recognition, except for any specifically restricted rights embodied in the recognition statute, such as hunting, fishing, and gaming rights. In addition, congressional recognition does not always come with a grant of reservation or trust territory (Carlson 2016). Also, regardless of the specific process behind a tribe’s recognition, all tribes remain vulnerable to congressional plenary power up to and including full termination of recognition and liquidation of land assets.

The specific matrix of land ownership on a particular reservation can have significant impacts on the de facto authority of tribes to effectively regulate various land-use activities. In instances where a reservation is predominately trust land in large contiguous parcels, land-use regulation is relatively straightforward, whether it is undertaken by the federal government under its trust responsibility or by the tribe itself under their self-governance authority. More commonly, tribes confront the checkerboard legacy of allotment, termination, and other policies. In these instances, land within a reservation is often an interspersed mix of communally held trust lands, individual Indian-held allotments, and non-Indian-held fee-simple land. Planning, coordination, and regulation of reservation territories in these situations are frequently a jurisdictional mess, as trust land management and Indian-held fee-simple lands are managed either by the federal government or the tribes themselves, whereas non-Indian-held land falls under the jurisdiction of state and county governments. Finally, for non-reservation tribes with no trust territory and heavily dispersed individual allotments, land management activity is severely diminished, for there is not much land to manage directly.

Self-governance status is another key factor in determining the range of land-use activities carried out by tribes. In the case of tribes that do not have or want self-governance authority, land-use decision making continues to be dominated by the federal government, although frequently decisions are made in direct consultation with tribes as a function of various collaborative governance mechanisms (Fischman 2005). For those tribes that are certified self-governance tribes, they may choose to seek direct delegated management authority over trust lands within their reservation. Yet self-governance authority is derived from a negotiated compact that covers a variety of programmatic areas of the tribe’s choosing, and a tribe may decline authority in certain areas, in which case implementation authority is retained by the federal government. That is to say, the status of a tribe as being a self-governance entity does not automatically imply that a tribe holds self-governance authority over all land management decisions within the reservation—just the operations that they choose to contract for.

Certain tribes hold significant land management roles and responsibilities that extend beyond tribally owned land and reservation boundaries. Tribal comanagement of natural resources, or “management in which government shares power with resource users, with each given specific rights and responsibilities relating to information and decision-making” (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2007), is a major area of activity for some tribes. There are at least three broad areas in which tribes participate as institutionalized comanagement partners: management of federal protected lands, management of migratory resources such as fish and game, and management of state and private lands upon which tribal resources depend. In the first category, a growing number of federal protected lands such as national parks, national monuments, wilderness areas, and other specialized units have established formal comanagement roles for certain Native American tribal governments. Making generalizations across these cases is difficult, however, as each formal grant of comanagement authority entails different specific comanagement responsibilities to be undertaken by tribes, and reflects different processes. Furthermore, there is no singular path toward the establishment of such comanagement roles. Some have argued that such “place-based collaboration” and the formalized collaborative decision-making institutions that are developed to facilitate comanagement must be approved by congressional statute (Fischman 2005, p. 199). A prime example of this process is the enabling legislation that created Canyon de Chelly National Monument, in which the Navajo retained ownership and most day-to-day management responsibilities of the monument, or that which created trust lands for the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe within Death Valley National Park, seventeen years after the tribe’s formal federal recognition (Fowler et al. 2003; King 2007). In other instances, comanagement derives from unique treaty rights that grant privileged access to areas adjacent to reservation lands (Nie 2008).

But there have been instances in which de facto comanagement has been developed as a function of agency discretion and negotiation with tribes in the absence of congressional approval, as in the Ti Bar Demonstration Project in California (Diver 2016). In other cases, comanagement has evolved from a similar bottom-up approach of initial negotiation and collaboration between the relevant administrative agency and tribe before formal codification via congressional statute, as in the case between the Bureau of Land Management and Cochiti Pueblo over management of Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument (Pinel and Pecos 2012), or between the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe for a wide range of management activities in the National Bison Range (Fischman 2005; King 2007). Furthermore, opportunities for comanagement can be an outgrowth of self-governance contracting, as occurred in Grand Portage National Monument between the National Park Service and the Grand Portage Band of Minnesota Chippewa, although this avenue appears to have occurred only once and reflected a unique set of circumstances (King 2007). Below the federal level, tribes have also been engaged in comanagement in various watershed management bodies convened by state governments (Cronin and Ostergren 2007). In instances where tribal advocacy has been instrumental in pushing for new national monument designations under the Antiquities Act, tribes have agitated for formalized comanagement roles, such as with Bears Ears National Monument (Ruple et al. 2016), a comanagement role that has been supported by the Trump administration despite its recent and unpopular (within Indian country) reduction in size (Eilperin 2017). That Secretary of Interior Zinke additionally suggested to the president that he seek congressional approval for tribal comanagement within other national monuments, including the proposed national monument designation of Badger-Two Medicine in Montana (Hegyi 2017), is perhaps a sign that the practice of tribal comanagement of federally protected lands is here to stay, even if it is judged by some to be merely a ploy for co-opting tribal interests (Spaeder and Feit 2005). There are no automatic opportunities for comanagement by tribes, however, and the openness to embracing comanagement is context-specific and likely dependent upon issue salience, political clout by tribes, effective tribal leadership, sufficient resources, the legacy of past relations between settlers and tribes, and the general milieu of support by elites and society in general for tribal sovereignty and self-governance, along with other factors (Cronin and Ostergren 2007; Day 2014).

Another class of comanagement arrangements involves tribes with specific reserved treaty rights and entails formalized comanagement between tribes and state fish and wildlife management agencies in situations that would otherwise normally represent unshared areas of state authority. For instance, several tribes in the Pacific Northwest have specific treaty provisions to fish “in usual and accustomed places” and “in common with the citizens” of the state (Singleton 1998). This rather innocuous-sounding treaty language has had far-reaching implications, as the courts, in response to conflicts largely surrounding the salmon fishery, soundly reaffirmed these rights and held that, as a shared fishery, tribes are entitled to a roughly 50% share of the resource along with regulatory comanagement authority with the states of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington (Singleton 1998). Similarly, eleven Ojibwa tribes in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin have had off-reservation treaty rights to hunting, fishing, and wild rice-gathering activities upheld by court order, and actively participate in data sharing, developing management plans, setting harvest goals, and conducting other activities with state departments of natural resources (Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission 2019; McClurken 2000). Furthermore, such rights have provided a gateway for tribes to participate in comanagement authority even at the international level, as in the case of the twenty-four treaty tribes of the Pacific Northwest who collectively hold commissioner and other high-level positions in the Pacific Salmon Commission (Day 2012).

Third, such reserved treaty rights may entail a significant land-use planning role for tribes involving activities occurring on private lands. For instance, in Washington State, the aforementioned fishing “treaty tribes” have long argued that the right is meaningless if the resource is severely depleted, and therefore tribes must have a prominent role in the protection of habitat that is necessary for the propagation of salmon. Such arguments were instrumental in the inclusion of the treaty tribes during the development of the Washington State Timber, Fish, and Wildlife Plan, which developed new rules governing logging practices on private forestlands that were designed to protect riparian zones and thereby improve salmon-rearing habitat (Flynn and Gunton 1996). The right to habitat protection has recently been codified in the courts by the so-called Martinez Decision, in which tribes successfully sued the state of Washington to mandate remediation of faulty road culverts that impede salmonid fish passage (Blumm 2017). An implication of this and other judicial decisions is that consultation with tribes will be mandated in advance of regulatory rulemaking for any land use or other activity that negatively affects salmon (and there are many) and thus the treaty right, although this will likely play out on a case-by-case basis (Blumm 2017).

Finally, an emergent land issue in response to climate change impacts is the wholesale relocation of Native American groups in response to catastrophic localized ecological changes. Because of the particular vulnerability of many Native American groups to climate change impacts, and the constrained range of adaptation options available to them, relocation of Native American groups in response to catastrophic localized ecological changes has recently become a specific class of adaptation response that has garnered much publicity. Recent land swaps involving the Quileute and Hoh Native American Tribes in Washington State, a proposed resettlement for the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe in Louisiana, various village resettlement initiatives for Alaska Native Village Corporations, and other cases have been trumpeted by the press and Native American activists as models for climate change adaptation strategies involving Native American tribes (see, e.g., Campbell and de Melker 2012; Davenport and Robertson 2016; Jackson 2016; Maldonado et al. 2013; Marshall 2016; Murphy 2009; Spanne 2016). These relocation efforts raise a variety of challenges regarding land-use planning and decision making on both tribal lands and in adjacent jurisdictions that are being proposed as potential relocation sites. The mere suggestion of a proposed relocation is a politically sensitive matter owing to the legacy of the Indian Removal period (Bronen 2011; Ford and Giles 2015). If such relocation is amenable to a tribe, planning is further hampered by enormous costs associated with securing an alternative land base and actual moving costs, such that most plans do not satisfy established cost-benefit guidelines (Bronen 2011). As a result, current efforts are focused on mitigation efforts such as sea wall construction that may only delay the inevitable need to relocate and that may not be cost-effective over the long run (Martin 2018). However, simply allowing entire communities to disappear would be a clear violation of the federal trust responsibility, such that relocation as an adaptation strategy is likely to be necessary and more commonplace in the future. In the interim, however, the list of implemented and in-progress relocation efforts suggests that the current prospects for relocation may be limited to situations in which an affected tribe has a small and remote existing land base adjacent to federally held tracts that provide for culturally appropriate land-use activities and that could be swapped if public opposition is low, political support for the tribe is high, and the interests of the administrative agency with oversight of the proposed tract are not significantly disrupted (Day 2019).

Conclusion

No two tribes have the same range of land management responsibilities. The means by which a tribe has attained federal recognition, the degree to which a tribe holds special reserve treaty rights, whether it engages in self-governance authority over federal trust lands, and the extent to which it has been significantly affected by allotment policies all condition the range of opportunities available to a tribal government to engage in particular land management activities. Furthermore, congressional plenary authority renders a tribe’s political status and authority tenuous and subject to the whims of Congress. Past federal policy has resulted in more entanglements with state governments than most tribal governments would prefer, and certain periods have entailed such low amounts of funding as to represent a failure of the federal government’s trust responsibility toward tribes and to diminish the capacity of tribes to carry out their authority and responsibilities. Despite the shadow of plenary authority, however, the modern era is marked by a more consistent policy orientation toward tribes, upholding the government-to-government relationship and generally supporting the expansion of tribal government responsibilities in areas that the tribes themselves wish to take on. As a result, the scope of tribal land management activities has expanded greatly in the last forty or so years and continues to evolve into new areas that have increased the complexity of intergovernmental relations between tribes, the federal government, and certain state governments. Understanding the specific land management responsibilities of a particular tribe necessitates an examination of its particular historical relationship with federal and state governments and the specific policies that have affected land tenure patterns and the distinctive land management issues facing a given tribe.

Legal Citations

- Johnson v. M’Intosh (21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823).

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831)); Worcester v. Georgia (31 U.S.(6 Pet.) 515 (1832)).

- Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (187 U.S. 553 (1903)).

- City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York (544 U.S. 197 (2005)).

References

Bernholz, Charles D., and Robert J. Weiner Jr. 2008. “The Palmer and Stevens ‘Usual and Accustomed Places’ Treaties in the Opinions of the Courts.” Government Information Quarterly 25: 778–95. (↵ Return)

Blumm, Michael C. 2017. “Indian Treaty Fishing Rights and the Environment: Affirming the Right to Habitat Protection and Restoration.” Washington Law Review 92(1): 1–38. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Bronen, Robin. 2011. “Climate-Induced Community Relocations: Creating an Adaptive Governance Framework Based in Human Rights Doctrine.” NYU Review of Law & Social Change 35(2): 356–406. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Campbell, K., and S. de Melker. 2012. “Climate Change Threatens the Tribe from ‘Twilight.’” PBS Newshour, July 16, 2012. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/science-july-dec12-quileute_07-05. (↵ Return)

Carlson, Kristen M. 2016. “Congress, Tribal Recognition, and Legislative-Administrative Multiplicity.” Indiana Law Journal 91(3): 955–1021. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Clow, Richmond L., and Imre Sutton. 2001. “Prologue: Tribes, Trusteeship, and Resource Management.” In Trusteeship in Change: Toward Tribal Autonomy in Resource Management, edited by Richmond L. Clow and Imre Sutton, xxix–liii. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. (↵ Return)

Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission. 2020. “Fisheries Timeline.” Last modified in 2019. https://www.critfc.org/about-us/fisheries-timeline/. (↵ Return)

Cronin, Amanda E., and David M. Ostergren. 2007. “Democracy, Participation, and Native American Tribes in Collaborative Watershed Management.” Society and Natural Resources 20(6): 527–42. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Cummings, Jody A. 2017. “Proposed Changes to Off-Reservation Trust Application Criteria and Acquisition Process.” Steptoe, October 30, 2017. https://www.steptoe.com/en/news-publications/proposed-changes-to-off-reservation-trust-application-criteria-and-acquisition-process.html. (↵ Return)

Davenport, Coral, and Campbell Robertson. 2016. “Resettling the First American ‘Climate Refugees.’” New York Times, May 2, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/03/us/resettling-the-first-american-climate-refugees.html. (↵ Return)

Day, Shane. 2012. “Indigenous Group Sovereignty and Participatory Authority in International Natural Resource Management Regimes.” Doctoral thesis, Indiana University. (↵ Return)

Day, Shane. 2014. “The Evolution of Elite and Societal Norms Pertaining to the Emergence of Federal-Tribal Co-Management of Natural Resources.” Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research 6(4): 291–96. (↵ Return)

Day, Shane. 2019. “Relocation of Native American Communities in Response to Climate Change: Current Initiatives and Future Challenges.” Paper presented at Western Political Science Association 2019 Annual Meeting, April 18–21, 2019, San Diego, California. (↵ Return)

Deloria, Vine, Jr., and Clifford M. Lytle. 1984. The Nations Within: The Past and Future of American Indian Sovereignty. Austin: University of Texas Press. (↵ Return)

Diver, Sibyl. 2016. “Co-management as a Catalyst: Pathways to Post-colonial Forestry in the Klamath Basin, California.” Human Ecology 44(5): 533–46. (↵ Return)

Duthu, N. Bruce. 2008. American Indians and the Law. New York: Penguin. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Eilperin, Juliet. 2017. “Shrink at Least 4 National Monuments and Modify a Half-Dozen Others, Zinke Tells Trump.” Washington Post, September 17, 2017. (↵ Return)

Fischman, Robert L. 2005. “Cooperative Federalism and Natural Resources Law.” NYU Environmental Law Journal 14(1): 179–231. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Flynn, Sarah, and Thomas I. Gunton. 1996. “Resolving Natural Resource Conflicts through Alternative Dispute Resolution: A Case Study of the Timber Fish Wildlife Agreement in Washington State.” Environment 23(2): 101–12. (↵ Return)

Ford, Jamie K., and Erick Giles. 2015. “Climate Change Adaptation in Indian Country: Tribal Regulation of Reservation Lands and Natural Resources.” William Mitchell Law Review 41(2): 519–51. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Fortunate Eagle, Adam. 1992. Alcatraz! Alcatraz! The Indian Occupation of 1969–1971. Berkeley: Heyday Books. (↵ Return)

Fowler, Catherine S., Pauline Esteves, Grace Goad, Bill Helmer, and Ken Watterson. 2003. “Caring for the Trees: Restoring Timbisha Shoshone Land Management Practices in Death Valley National Park.” Ecological Restoration 21(4): 302–6. (↵ Return)

Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission. 2019. “Treaty Rights Recognition and Affirmation.” Accessed November 12, 2019. https://www.glifwc.org/Recognition_Affirmation/. (↵ Return)

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development. 2008. The State of the Native Nations: Conditions under U.S. Policies of Self-Determination. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Hegyi, Nate. 2017. “Blackfeet Hesitant about Proposed National Monument at Badger-Two Medicine.” Montana Public Radio, October 19, 2017. https://www.mtpr.org/post/blackfeet-hesitant-about-proposed-national-monument-badger-two-medicine. (↵ Return)

Jackson, Ted. 2016. “Stay or Go? Isle de Jean Charles Families Wrestle with the Sea.” The Times-Picayune, September 13, 2016. http://www.nola.com/weather/index.ssf/2016/09/stay_or_go_isle_de_jean_charles_families_wrestle_with_the_sea.html. (↵ Return)

King, Mary Ann. 2007. “Co-management or Contracting? Agreements between Native American Tribes and the U.S. National Park Service Pursuant to the 1994 Tribal Self-Governance Act.” Harvard Environmental Law Review 31(2): 475–530. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Maldonado, Julie K., Christine Shearer, Robin Bronen, Kristina Peterson, and Heather Lazrus. 2013. “The Impact of Climate Change on Tribal Communities in the US: Displacement, Relocation, and Human Rights.” Climatic Change 120(3): 601–14. (↵ Return)

Marshall, Bob. 2016. “The People of Isle de Jean Charles Aren’t the Country’s First Climate Refugees.” The Lens, December 6, 2016. http://thelensnola.org/2016/12/06/the-people-of-isle-de-jean-charles-arent-the-countrys-first-climate-refugees. (↵ Return)

Martin, Amy. 2018. “An Alaskan Village Is Falling into the Sea. Washington Is Looking the Other Way.” Public Radio International, October 22, 2018. https://www.pri.org/stories/2018-10-22/alaskan-village-falling-sea-washington-looking-other-way. (↵ Return)

McClurken, James M. 2000. Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights. East Lansing: Michigan State Press. (↵ Return)

Murphy, Kim. 2009. “An Indian Reservation on the Move.” Los Angeles Times, February 1, 2009. http://articles.latimes.com/2009/feb/01/nation/na-hoh-reservation1. (↵ Return)

Nie, Martin. 2008. “The Use of Co-management and Protected Land-Use Designations to Protect Tribal Cultural Resources and Reserved Treaty Rights on Federal Lands.” Natural Resources Journal 48(3): 1–63. (↵ Return)

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2007. OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms. Paris: OECD. (↵ Return)

Pevar, Stephen L. 2012. The Rights of Indians and Tribes, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6) (↵ Return 7) (↵ Return 8) (↵ Return 9) (↵ Return 10) (↵ Return 11) (↵ Return 12) (↵ Return 13) (↵ Return 14) (↵ Return 15) (↵ Return 16) (↵ Return 17) (↵ Return 18)

Pinel, Sandra L., and Jacob Pecos. 2012. “Generating Co-management at Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument, New Mexico.” Environmental Management 49(3): 593–604. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Richards, Kent. 2005. “The Stevens Treaties of 1854–1855.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 106(3): 342–50. (↵ Return)

Royster, Judith V. 1995. “The Legacy of Allotment.” Arizona State Law Journal 27(1): 1–78. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Ruple, John C., Robert B. Keiter, and Andrew Ognibene. 2016. National Monuments and National Conservation Areas: A Comparison in Light of the Bears Ears Proposal. White Paper No. 2016–02. Salt Lake City: Wallace Stegner Center. (↵ Return)

Singleton, Sara. 1998. Constructing Cooperation: The Evolution of Institutions of Comanagement. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Smith, Jane M. 2013. Tribal Jurisdiction over Nonmembers: A Legal Overview. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. (↵ Return)

Spaeder, Harvey A., and Joseph J. Feit. 2005. “Co-management and Indigenous Communities: Barriers and Bridges to Decentralized Resource Management—Introduction.” Anthropologica 47(2): 147–54. (↵ Return)

Spanne, Autumn. 2016. “The Lucky Ones: Native American Tribe Receives $48m to Flee Climate Change.” The Guardian, March 23, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/mar/23/native-american-tribes-first-nations-climate-change-environment-indican-removal-act. (↵ Return)

Strommer, Geoffrey D., and Stephen D. Osborne. 2014. “The History, Status, and Future of Tribal Self-Governance under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act.” American Indian Law Review 39 (1): 1–75. (↵ Return)

US Government Accountability Office. 2018. Broadband Internet: FCC’s Data Overstate Access on Tribal Lands. GAO-18-630. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office.

Wessendorf, Kathrin. 2011. The Indigenous World 2011. Copenhagen: INternational Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. https://www.iwgia.org/images/publications/0454_THE_INDIGENOUS_ORLD-2011_eb.pdf. (↵ Return)

Wilkins, David E., and Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark. 2011. American Indian Politics and the American Political System, 3rd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)