Colonial Agriculture

3.1 Crop Exchanges before the Industrial Revolution

The migration of the human population meant that the movement of crops away from their centers of origin was inevitable. Domesticated plant species first spread to neighboring regions via nomadic pastoralists, who traded with various farming communities. As tribal wars broke out, the grains were also looted and brought to new territories. However, this spread was limited.

Credit for the initial global spread of cultivated plants (3,000 BCE to 1,000 CE) goes to the ancient Polynesian seafarers, who sailed between Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America. They helped at least eighty-four cultivated plants travel from South America to Asia and Africa (e.g., maize, amaranth, cashews, pineapples, custard apples, peanuts, pumpkins, gourds, arrowroot, guava, sunflowers, basil, and brahmi). They also brought hemp and another fifteen plants to Africa and South America from Asia. These exchanges occurred long before Europeans were aware of the existence of the Americas (1).

The second global wave of exchange ensued via the Silk Road. The first highway that connected Asia to Europe and Africa, it was built by the emperors of the Han dynasty between the second century BCE and the first century CE. It was not a single road but a network of several routes that connected various regions of China. The silk collected from many provinces in China and sent west through its primary northern route gave it its name. Later, this route was extended to Rome via Central Asia, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, while a branch from Tibet also connected India. At its peak, the Silk Road network covered 7,000 miles, much of which ran through large desert areas with sporadic human inhabitation, where water and food sources were scarce and a constant fear of robbers loomed. Thus travel on the Silk Road was not for everyone. Only Arabs, the inhabitants of Central and Middle Eastern Asia who possessed generational experience surviving in the desert and had tribal networks to rely on, were successful in traversing the Silk Road and thus dominated trade. They traveled on camels across the desert in caravans protected by armed squadrons. They stopped at meeting points where traders heading to different destinations exchanged goods, like silk, cotton, sugar, spices, china, ivory, and precious stones. Traveling alone was not an option, so individuals, small groups, missionaries, and pilgrims also joined the traders’ caravans. For centuries, Arab merchants, travelers, and Sufis played a central role in the exchange of seeds and germplasm among the three continents. From India and China, they transported cotton, sugarcane, eggplants, and bananas to Central Asia and Africa; from Central Asia, they carried pomegranates, chickpeas, gram, pears, walnuts, pistachios, dates, fennel, carrots, onions, and garlic to India and China. From Africa, they procured millet, melons, coffee, and many tubers for Asia and Europe. Some sovereigns and their armies also unintentionally assisted in carrying germplasm across the Silk Road.[1]

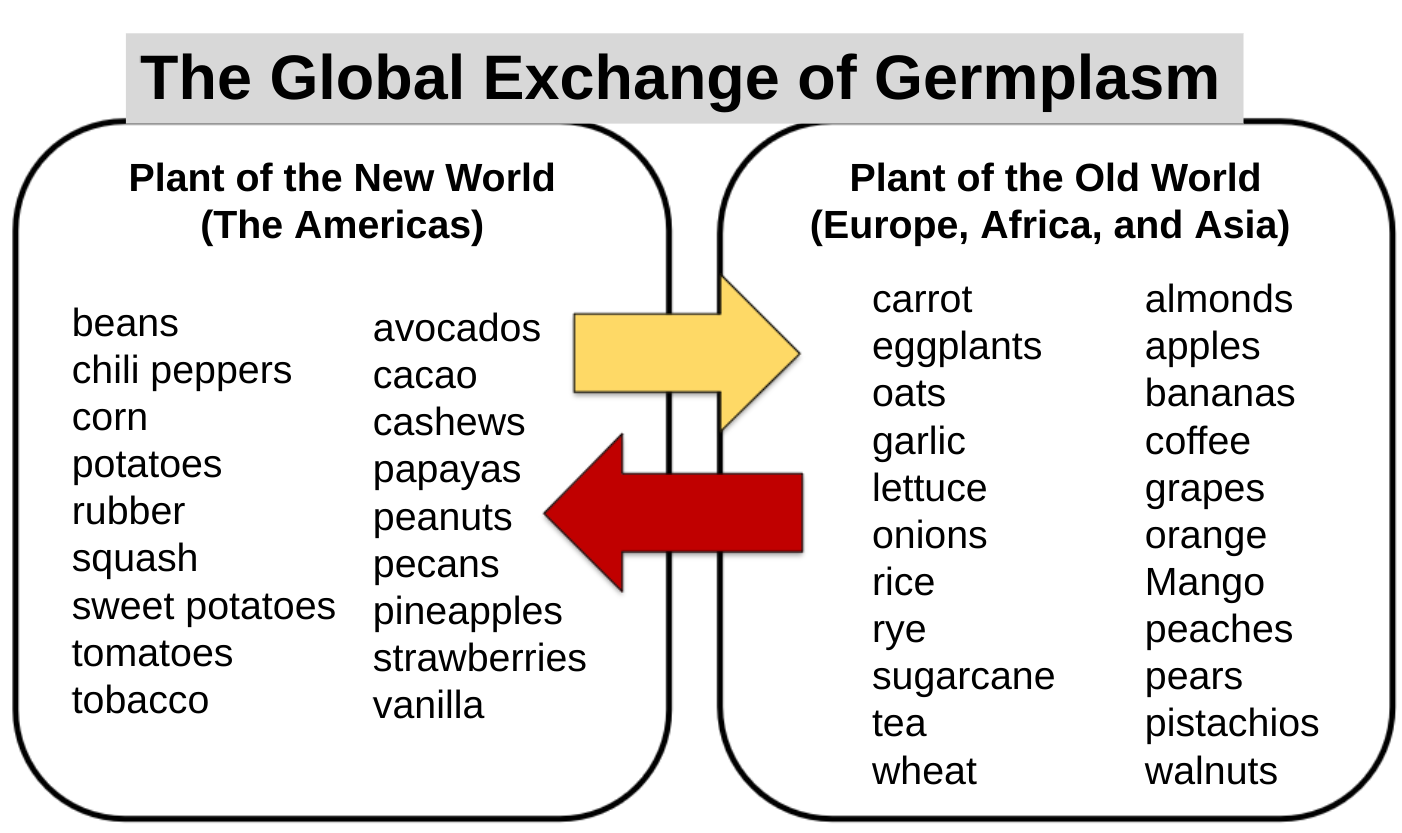

3.2 The Columbian Exchange

The third and the most dominant wave of global plant germplasm exchange occurred between the Age of Exploration and the Industrial Revolution under European imperialists. They promoted and invested in the systematic cataloging and classification of the fauna and flora found across the seven continents, transporting germplasm in bulk and establishing plantations of cash crops worked by enslaved peoples. This massive germplasm exchange between the Old World (Asia, Europe, and Africa) and New World (the Americas and various archipelagoes) is known as the Columbian Exchange (see figure 3.1).

You might be surprised to learn that until the eighteenth century, the peoples of Asia, Europe, and Africa had not seen potatoes, tomatoes, corn, sweet potatoes, or peppers, which are now an integral part of their traditional cuisines. Acceptance of the introduced food crops in their new homes was slow, integration in the local cuisines was gradual, and acceptance in some cases was challenging. For instance, potatoes were brought from Peru to Spain in the sixteenth century, reaching Italy from Spain in 1560. However, it took more than a hundred years for Europeans to accept the potato as food. When it first arrived in Europe, there were rumors that eating potatoes cause leprosy. In the seventeenth century, Irish peasants adopted the crop due to difficult circumstances: invasion, famine, and evictions from their fertile land. They embraced the potato because it was a highly productive crop that could be grown even on the smallest amount of cultivated land.

During the eighteenth century, potatoes were successfully introduced in Germany due to frequent crop failures, but the French population was still apprehensive despite famine and starvation. The French eventually accepted potatoes in the late eighteenth century after much encouragement from Queen Marie Antoinette. Marie adorned her hair with potato flowers and commissioned a portrait of herself with a potato plant. She also asked gardeners to plant potatoes in the royal gardens, where guards were stationed during the day but cleverly called away at nighttime. Common folks would dig potatoes from the royal garden at night and sow them in their fields.

Later, Europeans introduced potatoes to the Ural Mountains and their colonies in Asia and Africa. For example, the British brought them to India, and in the mid-nineteenth century, officials from the Geological Survey of India sowed potatoes in the slopes of the Himalayas. Potatoes proved to be a very productive and nutritional crop in most areas and, by the middle of the nineteenth century, became an integral part of diets across Europe and Asia. Today, the potato is the most popular and affordable vegetable in the world. In Africa and Central Asia, many traditional cuisines use potatoes and chicken as their main ingredients, even though the domesticated animal’s birthplace is China and the vegetable’s is Peru.

Similarly, tomatoes, onions, and garlic, used in abundance in Italian cuisine, were introduced to the country only 400 years ago. Red chilies, bell peppers, pumpkins, gourds, squash, and so on spread all over the world from South America over the past three centuries. Likewise, mangoes, jackfruit, eggplants, cotton, sugarcane, and so on spread out of South Asia. This history of the introduction of cultivated plants shows us that many traditional cuisines are not as old as they are thought to be. Despite the strong sense of cultural identity we ascribe to them, they are constantly evolving and incorporating new ingredients.

We find that across cultures and religions, some food items are revered, whereas others are prohibited. During Hanukkah, Jewish people traditionally make latkes (a special pancake made of potatoes), and they eat unleavened bread, matzo, during Passover. Hindus offer basil, barley, sugarcane, sesame, and rice to their gods with their prayers. For Africans, cassava and yam are staples, but red rice is sacred and saved for special occasions. It seems that a sense of reverence for particular foods may be linked to historical memories of crop domestication because, in many cases, the revered foods are prepared from crops that are native to the areas those people lived. In contrast, apprehensions are usually associated with crops that were introduced later. For example, some vegetarian Hindu sects abstain from eating garlic and onion, as these plants were introduced from Central Asia. At the root of this prejudice is doubt and fear of the unfamiliar. Such reverence or prejudice may not seem to make logical sense but may trace back to experiences with the domestication and/or introduction of the crop in the past.

Scholars estimate one-third of all food crops grown in the world today are of American origin and were unknown to the Old World before the conquest of the Americas. Over time, these crops became integrated into European, Asian, and African cuisines. Likewise, foods previously unknown in the Americas—such as sugarcane, tea, coffee, oranges, rice, wheat, eggplants, bananas, mangoes, and so on—were brought over by European colonists. Overall, this global exchange of plant species and their cultivation at the industrial scale brought uniformity to the consumer market and actually flattened the diversity known to previous generations. In total, to date, 250,000 species of flora are known, out of which humans can identify some 30,000 plant species as edible, but only 120 are cultivated. Of these, eleven crops—wheat, maize, rice, potatoes, barley, sweet potatoes, cassava, soybeans, oats, sorghum, and millet—satisfy 75 percent of human nutritional needs, and wheat, maize, and rice alone make up more than 50 percent of the entire population’s daily caloric intake.

3.3 The Rise of European Imperialism and Plantations

From the seventh century until the seventeenth century, Arabs controlled Silk Road trade. The luxurious goods they brought from China and India were first sold to the sultans of Central Asia, and the remaining items were sold in Europe. As a consequence, only a few valuable goods were auctioned in Europe, where the kings and noble classes bid on their favorite items. Arab traders made tremendous profits and controlled the market: they determined what to sell, where to sell, and at what price. In contrast, Europe had nothing of value to barter and thus had to make their payments in gold or silver. European economic thought and policies until the 1700s were based on the mercantile system, wherein economic and political stability rely on restrained imports and excessive exports. Thus unilateral trade with Arabs caused fear among the European sovereigns, who worried about the diminishment of their treasuries of gold and silver.

So in the fifteenth century, the rulers of Portugal poured their resources into developing better ships, navigational equipment, watches, maps of the world, and so on and recruited Europe’s best sailors to lead armed naval squads for exploration. The Portuguese managed to reach the Canary and Azores Islands, the Caribbean, Brazil, Africa, China, India, and Southeast Asia by sea. Soon Spain, France, Britain, and Holland also managed to reach the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Thus Christopher Columbus reached the Caribbean islands in 1492, and five years later, in 1497, Vasco da Gama reached the port of Calicut in India. For the first time, Europeans saw many new crops, fruits, vegetables, ornamental plants, herbs, cattle, and other species of animals from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. From the sixteenth to nineteenth century, the various European powers competed with one another for control over the newfound lands and their wealth. Gradually, all the countries of Africa, the Americas, and Asia became European colonies.

European rulers employed new management systems in their colonies. They organized agriculture to focus on the establishment of plantations of cash crops, replacing traditional farming to maximize profits. First, sugar plantations were established in the Caribbean by exploiting slave labor, and later, this model was repeated to produce tea, coffee, cocoa, poppy, rubber, indigo, and cotton in Asia, the Americas, and Africa. The products of plantations were for the distant European markets and not for the consumption of local populations. Often, the crops and the laborers were brought to plantations from different continents. Thus colonial agriculture caused the global displacement of many people and plants.

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, the story of agriculture centered on these plantations’ products and their availability at a cheap price in the global market. Europe’s sovereign class made huge profits, and the continent prospered tremendously, but at the cost of exploiting the natural resources of the colonies and relying on slavery. Increasing trade between Europe and the colonies also affected business and trade practices during the 1500s and 1600s, which had a great impact on all spheres of society and human civilization. With this also came the Enlightenment and the birth of the ideas of democracy and universal equality. We see that massive change in agricultural practices added several new layers of complexity to human civilization, politics, and economics and eventually changed the world order forever.

In the rest of this chapter, we will explore colonial agriculture and its impact on human society through the stories of three representative plantation products: sugar, tea, and coffee.

3.4 The Story of Sugar and Slavery

3.4.1 The Discovery of Sugar

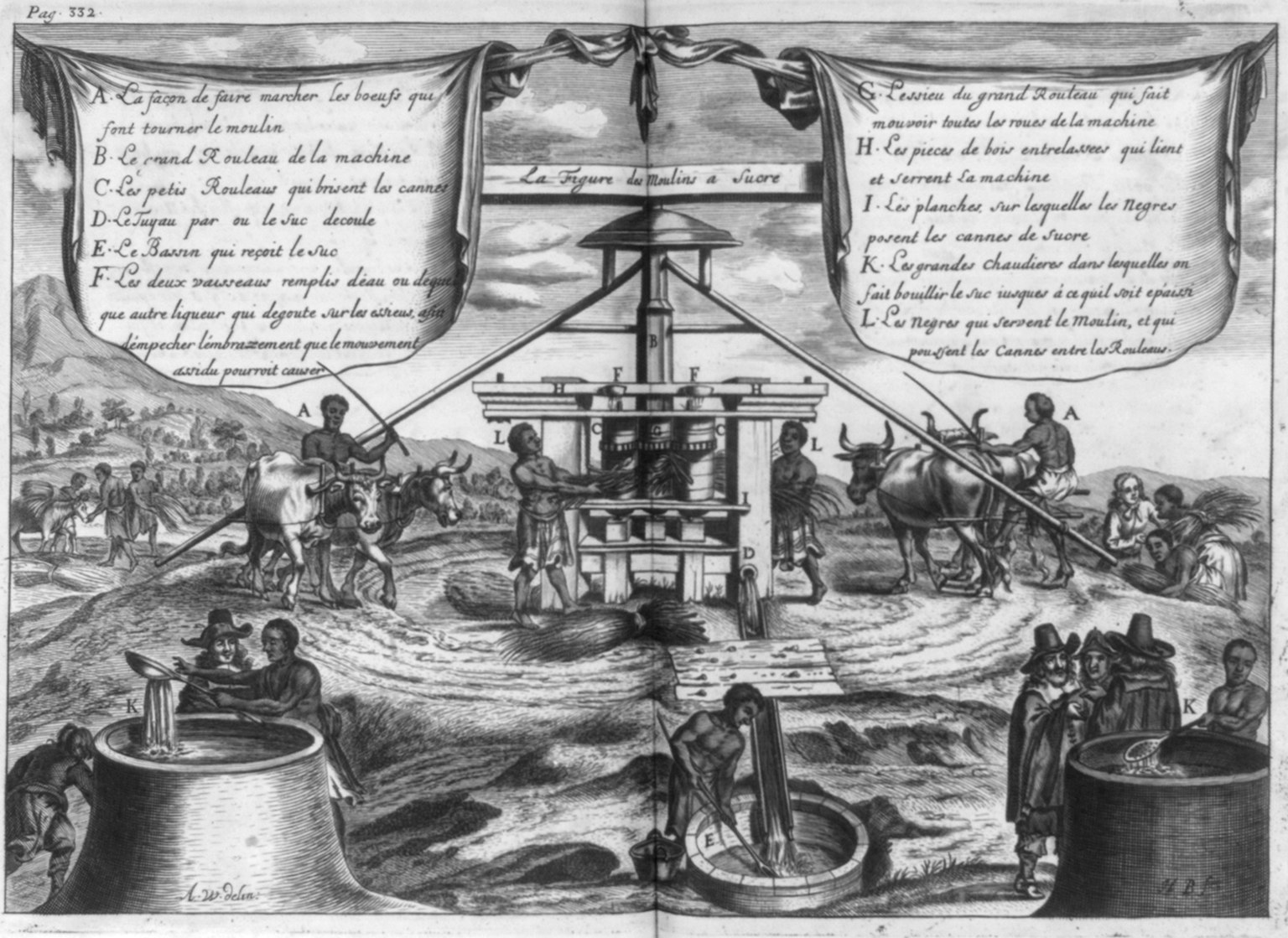

Sugarcane, a plant from the grass family, is the major source of sugar. It is a tropical crop, requiring an abundance of water and sunshine for optimum growth, and is easily damaged by frost and low temperatures. It has a very long and prominent stalk or stem (about twelve feet) that is filled with juicy fibers containing large amounts of sucrose. People enjoy chewing small pieces of the stem to consume its juice directly. This juice is also used for making sweets, puddings, and sugar (see figure 3.2).

Sugarcane is a plant native to South and East Asia (covering India, Indonesia, China, and New Guinea), where its six species are found. The sweetest and the most cultivated variety of sugarcane, known as Saccharum officinarum (see figure 3.3), is believed to have originated in New Guinea or Indonesia and was introduced to many South Asian countries 3,000–5,000 years ago by Polynesian sailors. Where and how the cultivation of sugarcane began remains unknown. The earliest written reference to the sugarcane reed is a Vedic Hindu text known as the Atharvaveda (which is 3,500 years old), where the use of ikshu (desire), the Sanskrit name for sugarcane, appears several times. It is not surprising that the sweetest plant on earth was called “desire,” as sweetness is the most primitive human craving, the first taste that settles in our consciousness. We use sweet as an adjective to evaluate and describe the most positive, emotionally fulfilling, and abstract aesthetic experiences.

The second-oldest written reference to sugarcane is from the Greek philosopher Herodotus (484–425 BCE). Within a hundred years of Herodotus, Kauṭilya (ca. 350–283 BCE) described five types of sugar in his book Arthaśāstra.[2] This is the first ancient description of sugar making in the world. It is likely that in India, people learned to make sugar 2,000 years ago and developed pressing mills to extract large quantities of juice from the cane, as well as facilities for boiling the juice and extracting sugar. However, people outside of the Indian subcontinent remained largely ignorant of it until much later.

For the first time, in the seventh century, Arab traders introduced raw sugar (a.k.a. khand) to Central Asia. There, artisans invented tedious protocols for the purification and crystallization of it, thus making white granulated sugar, sugar cubes, and sugar figurines. Initially, white sugar was made in very small quantities and was so very costly that it was known as “white gold.” White granulated sugar was not made available in India for a long time; the raw material continued to come from India, but for centuries, the advanced technology for making granulated sugar was not known in the country. It wasn’t until the thirteenth century that the technique for making it reached India from China, and that is why it is called “Cheeni” in India today.

In the eleventh century, both raw khand and white processed sugar reached the royals and lords of Europe. The word candy was coined for khand, and sucre, sacrum, sucrose, and sugar for the white variety. Before this, Europeans had never known such extreme sweetness, and they went crazy for it. It was so addictive that they were willing to plunder their stores of gold and silver in exchange for just a few pounds of it. But while the demand for sugar was high, so little was available that not even 1 percent of that demand could be met. It is said that once, England’s King Henry IV went to considerable lengths to get just four pounds of sugar, but it could not be arranged.

The Arabs realized that there is an immense scope for expanding the highly profitable sugar trade. Islamic rulers (of Arab origin) who dominated India and Central Asia from the seventh century onward focused on increasing the production of sugar: they organized large farms for sugarcane cultivation under the leadership of landlords. These landlords set up sugar factories in the reed fields because cut sugarcane deteriorates rapidly and so must be milled within twenty-four hours. In these fields, armies of workers continuously worked, cutting and transporting sugarcane to the factory, where artisans would extract the juice and pass it along for boiling and further processing. This marked the first time in human civilization that excessive human labor was organized for cultivating a cash crop to be sold in distant markets: these were the first plantations.

Due to the efforts of the Islamic rulers, sugar production doubled, but demand quadrupled. Arab merchants could not meet the demands of sugar in Central Asia or Europe; fulfilling it was beyond their ability. There were two main obstacles: first, they had a limited amount of fuel for making sugar, and second, only a modest amount could be transported to Europe via camels and horse convoys.

3.4.2 Caribbean Sugar Colonies

Strange as it may seem, until the sixteenth century, most people in the world did not know about sugar. The sweetest thing they had known was honey, and that too was available only in small quantities. The Portuguese were the first to invest in commercial sugar plantations. They used their newly founded colonies in the Caribbean for sugarcane cultivation, where fuel for running the factories was plentiful and goods could be easily shipped worldwide. However, they were short on the workers needed to establish the plantations and run the factories. So they turned to West Africa, where they were heavily involved in the plunder of ivory. In 1505, they brought the first ship carrying enslaved Africans to the Caribbean to establish a sugar colony. Over the next twenty years, with the constant toiling of slaves, the Portuguese sugar colonies expanded from Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) to Brazil.

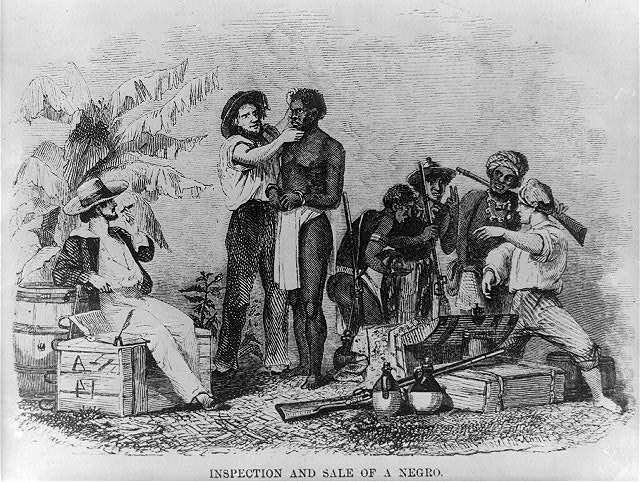

Soon Spain, France, Britain, and Holland followed their example and established sugar colonies in the Caribbean islands, Guyana, Suriname, Brazil, Cameroon, and elsewhere. As the sugar industry expanded, the slave trade also grew to new peaks. In mainland Europe, many companies were formed around it (see figure 3.4 for a depiction of a regular scene at the slave market). For the next 300 years, the slave trade continued unabated. By the middle of the nineteenth century, a million Africans had been enslaved and brought to the Caribbean islands and Brazil. As a consequence, sugar production increased, and supply reached the common folks of Europe.

The owners of the sugar colonies, who profited from the slavery-based sugar industry, were important officials and members of influential families in Europe. While still residing in their native countries, they made tremendous amounts of money from their estates in the colonies. Although they seldom visited, each often maintained a plush bungalow on a high hill within the plantation, known as the “Great House.” The daily management of the sugar estate was left in the hands of a supervisor or slave commander (figure 3.5). The owner did not directly engage in the dirty work of interacting with the people he enslaved on a day-to-day basis. Slavery became an accepted social institution, and surprisingly, the task of its operation was shouldered by the slaves themselves. Usually, they worked for sixteen to eighteen hours a day, did not get enough food, and were not allowed to leave. They were punished and tortured routinely and could be murdered for raising a slight objection. It was common for them to die every day due to torture, hunger, and sickness. New slaves immediately replaced the dead. The eighteen- to twenty-year-old youth who were brought to sugar colonies from Africa usually died within ten years. A sense of the inhumane conditions of slave life can be drawn from the fact that from 1700 to 1810, 252,500 African slaves were brought to Barbados, a small island of 166 square miles, and 662,400 to Jamaica.

From 1600 to 1800, the sugar trade was the most profitable business in the world. It was a large part of “triangular trade,” wherein companies involved in the slave trade sold slaves in the Caribbean in exchange for sugars, then sugar was sold in Europe, and from Europe, armed sailors were sent to Africa for more slaves. This cycle continued for 300 years and ensured an uninterrupted supply of sugar was being sent to Europe. By the eighteenth century, sugar production in the Caribbean was so high that it became available to ordinary people at a very affordable price. However, many Europeans remained ignorant of the inhumane conditions of slaves working within the sugar colonies.

3.4.3 The End of Slavery in the Caribbean

In 1781, a public lawsuit in England that involved a Liverpool-based slave-trading company and an insurance company brought the slave trade under public scrutiny. The slave-trading company’s ship, Jong, lost its way, and officers onboard foresaw a shortage of drinking water in the ship due to the delayed schedule. To avoid inconvenience due to a drinking water shortage on the ship, they threw 142 slaves from the ship into the open sea. The slave-trading company had insurance on the lives of the slaves, and accordingly, they demanded compensation from the insurance company. However, the insurance company did not consider the “property damage” to be justified and refused to pay compensation. In response, the Slave Trading Company sued them. The news of this lawsuit was published in the newspapers of England, and a public conversation on slavery began.

Quakers organized and led protests against the killings, and, in 1783, 300 Quakers appealed to the British Parliament to end slavery. The appeal was dismissed. All the influential British citizens of that time, including the members of parliament and their relatives, owned sugar estates in the Caribbean; their economic interests were directly tied to the slave trade. For example, lord mayor of London William Beckford, who was also a member of parliament, had twenty-four sugar plantations in Jamaica; another parliament member, John Gladstone (father of the future British prime minister William Gladstone), owned a sugar colony in British Guiana. Therefore, it was no surprise that the Quakers’ proposal was rejected in parliament. However, the Quakers were not discouraged. They started the abolitionist movement,[3] boycotting sugar on moral grounds and urging the public to do the same. They reached out to various individuals, groups, and organizations to educate people about slavery and recruit supporters. They approached people from both the lower as well as elite classes and tirelessly campaigned against slavery.

Among the top activists of the abolitionist movement, Thomas Clarkson (figure 3.6) is particularly notable. In 1785, when he was a student at Cambridge University, he participated in the annual essay competition. The subject of that year’s essay, “The Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species,” was proposed by Peter Peckard, then the chancellor of Cambridge and a well-known abolitionist himself. Thomas Clarkson received first prize in the competition, and in writing the essay, what he learned about the cruel system of slavery made a lasting impact on him. The essay was published, and soon, he was introduced to several prominent leaders of the abolitionist movement, including James Remje and Grenville Sharp. Later, he became a full-time activist and dedicated his life to the cause.

Clarkson gathered testimonies from doctors who worked on slave ships and military men who had served in the Caribbean crushing the slave rebellions. He acquired the various instruments of torture (handcuffs, fetters, whips, bars, etc.) used on slaves to educate British citizens about the cruelty inflicted on the slaves within the sugar estates. He traveled 35,000 miles on horseback to collaborate with antislavery organizations and individuals. Clarkson also recruited supporters from influential political circles, such as parliament member William Wilberforce, who appealed twice to the British parliament to abolish the slave trade. His appeal was dismissed the first time, but the second time, in 1806, it passed under the heavy pressure of public opinion. Finally, in 1807, the slave trade was outlawed throughout the British Empire. The famous English film Amazing Grace is based on these efforts. In March 1807, on the final passing of the Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, the poet William Wordsworth wrote the following sonnet in praise of Thomas Clarkson:

Clarkson! it was an obstinate Hill to climb:

How toilsome, nay how dire it was, by Thee

Is known—by none, perhaps, so feelingly;

But Thou, who, starting in thy fervent prime,

Didst first lead forth this pilgrimage sublime,

Hast heard the constant Voice its charge repeat,

Which, out of thy young heart’s oracular seat,

First roused thee—O true yoke-fellow of Time

With unabating effort, see, the palm

Is won, and by all Nations shall be worn!

The bloody Writing is forever torn,

And Thou henceforth wilt have a good Man’s calm,

A great Man’s happiness; thy zeal shall find

Repose at length, firm Friend of human kind!

Although this was a significant triumph, slavery did not end. British companies stopped buying and selling slaves, but over the next thirty years, slaves continued to work as before in the plantations and mines located within the British Empire, and new slaves were supplied by other European companies as needed. Therefore, the struggle against slavery continued.

Apart from abolitionists, many others also played a crucial role in the antislavery struggle. In 1823, an idealistic clergyman, John Smith, went on a mission to British Guiana, where John Gladstone had a sugar estate. Pastor Smith narrated the story of Moses to the slaves there, describing how thousands of years ago, the Jewish slaves of Egypt gained their freedom and reached Israel. Inspired by this biblical story, 3,000 African slaves revolted. However, the rebellion was quickly suppressed, most of the rebels were killed, and Pastor Smith was sentenced to death, though Smith died on the ship carrying him back to England for execution.

British commoners were enraged by the death of Smith, which provided momentum to the antislavery movement. For the next ten years, they organized frequent antislavery protests and massive rallies while, in the sugar colonies, slave revolts continued. Finally, again under the pressure of public opinion, in 1833, the British Parliament passed the Emancipation Bill, which resulted in the legal abolition of slavery within the British Empire. The owners of the plantations were given seven years and subsidies to free their slaves. Finally, all slaves within the British Empire were legally freed on August 1, 1838.

3.4.4 Haiti: The First Free Country of Slaves

Around the time the abolitionists were campaigning to end slavery in England, the French Revolution (1789–99) began. At the time, a revolt erupted in the most valued French sugar colony, St. Dominic. Slave commanders ran the plantations in St. Dominic, where there were 25,000 whites, 22,000 freed Africans (including the slave commanders), and 700,000 slaves. The revolt was organized by slave commanders who pledged to liberate Haiti under the leadership of Toussaint, who called himself L’Ouverture (the opening). The slaves’ destiny was tied to the sugar plantations and the factories, so they burned them. In the wake of the ongoing turmoil within France, the temporary government of France, formed after the abolition of the monarchy, saw no way to quell this uprising and liberated St. Dominic in 1793. Thus St. Dominic became Haiti, the first free country of slaves.

However, when France withdrew, Britain moved forward to take control of Haiti. British soldiers began capturing the people of Haiti and returning them to the plantations as slaves. The fight continued for another five years. Eventually, in 1798, the British gave up, and Haiti became free again. But this freedom was also short-lived. In 1799, Napoleon came to power, and he overturned the law that had freed the slaves and attacked Haiti. French troops imprisoned the rebel leader Toussaint, who died in prison in 1803. Nonetheless, the people of Haiti continued fighting Napoleon’s army, resulting in the deaths of 50,000 French soldiers, and France suffered substantial economic losses. In 1804, France retreated, and Haiti finally became a free republic.

3.4.5 The American Sugar Colonies of Hawaii and Louisiana

Napoleon sold the French province of Louisiana to President Thomas Jefferson for just $15 million to make up for the enormous losses in the war with Haiti. Some of the former owners of the Caribbean sugar plantations started fresh in Louisiana.

Louisiana is suitable for sugarcane cultivation. However, it has a mild frost in the winter months, and thus sugarcane crop needs to be harvested from October to December. The additional burden of this weather also fell on the slaves, and therefore working conditions for slaves became even worse in Louisiana. Slavery continued in the United States of America until 1862. On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation and declared “that all persons held as slaves are, and henceforward shall be free.” Abraham Lincoln was also the first US president who established diplomatic relations with Haiti.

Some of the former owners of the Caribbean sugar colonies chose to settle in Hawaii. The conditions were very favorable for the planters, as sugarcane farming had been underway for a long time there. It is believed that in the early twelfth century, Polynesians brought sugarcane to Hawaii from South Asia. Hawaiians used sugarcane juice in many ways, although they did not learn to make sugar. The owners of plantations in Hawaii developed a new model for recruiting workers. Instead of African slaves, they employed workers from Asian countries at meager wages. First, only men from China were recruited. When these workers demanded better wages and working conditions, they brought workers from Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Spain, and Portugal. The workers of Hawaii were divided into different linguistic, ethnic, and cultural groups, and hence they could not organize to challenge the owners. The owner successfully managed their plantations and gained tremendous profits from the sugar business for nearly a century and a half. The living and working conditions of the workers were unfair and cruel, but it was an improvement compared to slavery: they received wages for their work, had families, and the owners could not sell them and their children. It was a significant accomplishment that, thanks to abolitionists, in the nineteenth century, legal slavery ended, and plantation owners were obliged to pay wages. In 1959, Hawaii became the fiftieth state of the United States of America.

3.4.6 Indentured Labor: Girmitiya

In 1836, John Gladstone wrote a letter to the then viceroy of India, asking him to send laborers for his sugar estate. The viceroy gladly accepted Gladstone’s proposal and sent 2,000 workers from India to British Guiana on a five-year work permit, along with the provisions for a paid trip back home. Like Gladstone, others made arrangements to bring indentured laborers from India when the slaves were freed (see figure 3.7). These workers carrying permits were sent to several British colonies—including Guyana, Mauritius, Suriname, the Caribbean islands, and South Africa—to work in plantations and mines.

The indentured workers couldn’t pronounce the word permit and instead referred to it as “Girmit,” and themselves as “Girmitiya”. After a long sea voyage of two to three months, when the Girmitiya reached their destination, they were received by the overseers and were assigned the quarters of the former slaves. The Girmitiya were helpless in a foreign land and could survive only at the mercy of the owners. They worked long hours, earned less money than promised, and were treated as slaves in all practical matters.

With the arrival of indentured workers, freed slaves lost opportunities for employment, and the owners got the upper hand in setting wages. So despite the freedom they’d earned after tremendous sacrifice and struggle, former slaves remained marginalized. The European owners deliberately created a situation in which indentured workers, former slaves, and other marginalized groups all remained in competition with one another. The masters of the plantations (and also the mines) thought of Indian workers as weak, obedient children and former slaves as foolish and lazy. The owners did not pay fair wages to either: in most places, the indentured workers received even poorer wages than the former slaves. Indentured labor was cheaper than free slaves, and the indentured workers were not in a position to organize and demand fair treatment or familiarized with the historical exploitation of slaves. Thus, the planters were treating them worse than free slaves. They were the replacement of former slaves.

3.4.7 The End of the Indentured Workers System

From 1860 onward, indentured workers from India were being brought to work in plantations and mines in South Africa. After the end of a five-year contract, indentured workers were offered two options: to return to India or live as a free worker who received a small plot of land in lieu of his passage home. Returning to India was not easy; Hindu workers who had crossed the sea faced social stigma back home. Thus most people chose to stay in South Africa to start their lives afresh. They often still worked in plantations and mines, but as free workers, and on the side, they served as small-time artisans, grew some fruits and vegetables on their plots, and set up small shops. Girmitiya brought many nuts and vegetable seeds with them from India. They grew local fruits, vegetables, and corn as well as Indian crops like mangoes. In the early years, their trade remained limited to their community. While the Indian population was small in number, the chance of their having direct encounters with the whites was negligible. The relationship between whites and Indians was more like that between an owner and a slave. But gradually the number of people of Indian origin increased. Apart from laborers, a large number of Muslim and Parasi traders from Gujarat also started coming to South Africa for business. Indian shopkeepers were polite, fair, and nonintimidating to Africans. As a result, many local Africans became their customers, which infuriated the white business community of South Africa.

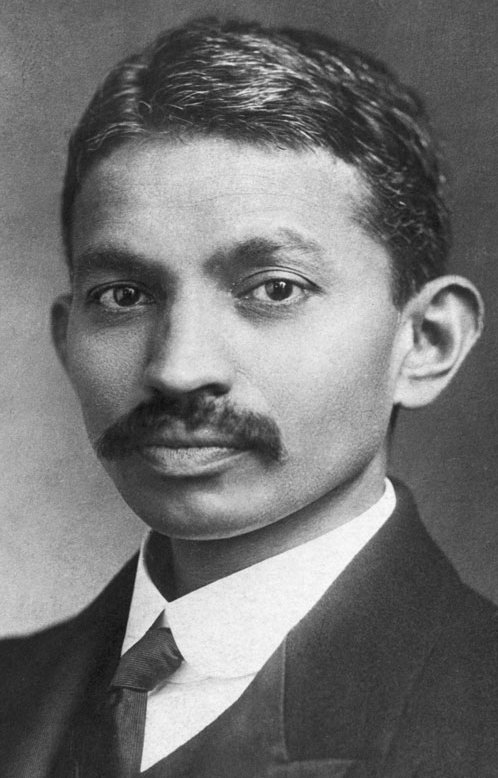

In 1893, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (figure 3.8) reached South Africa for the first time to assist a Gujarati businessman Dada Abdullah in a legal case. At that time, 50,000 Indian workers (freed after contract) and 100,000 indentured workers and their offspring were living in South Africa. He faced many insults and racial discrimination as a person of color despite being highly educated. He soon realized that Indians suffered more racist violence and social discrimination in South Africa than in Europe. Gradually he became an activist and began to lead civil rights movements in South Africa. His encounters with indentured workers were eye-opening, and he realized that the situations Indian indentured workers faced were in some ways worse than those of former slaves.

For the next twenty-one years, Gandhi served as an advocate for the Indian traders, small shopkeepers, and plantation and mine workers. He led a struggle against the policies of apartheid, resulting in the abolition of many discriminatory laws. While in South Africa, Gandhi established communication with the leaders of the Indian Freedom Movement and was successful in inviting a senior congressional leader, Gopalakrishna Gokhale, to South Africa. Gokhale witnessed firsthand the plight of indentured workers living outside of India. After returning home, Gokhale appealed to ban the indentured worker system. Finally, in 1917, the practice ended.

Unlike the strategies used in previous battles within the colonies, Gandhi relied on satyagraha (emphasizing the human commonality and truth) and the principle of nonviolence to fight the state of South Africa. His satyagraha experiments in Africa were instrumental to his future work. Gandhi returned to India in 1918 and led the freedom struggle there for the next thirty years, guided by the same principles, until India gained freedom in 1947.

3.4.8 Sugar from Sugar Beets

A method for making sugar from sugar beets was discovered in 1747 by German scientist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf. Marggraf’s student Franz Karl Achard successfully employed selective breeding for improving sugar content in beets and then opened the world’s first factory for extracting it in Silesia in the year 1801. Napoleon Bonaparte became interested in the idea of beet sugar. Sugar beets required less labor and fuel than sugarcane and could be easily grown in the cold climate of Europe. Under Napoleon’s patronage, the cultivation of beet sugar was promoted, and many factories and training schools were established. In 1812, Benjamin Dalesart discovered a method of extracting it on an industrial scale, which made it so that France could rely on beet sugar. In 1813, Napoleon prohibited the import of cane sugar from the Caribbean and further promoted beet sugar production. By 1837, France had 542 sugar mills and became the largest beet sugar producer in the world, producing 35,000 tons annually. Many other European countries, including Germany, followed France’s lead. In the United States, beet sugar production began in 1890 in the states of California and Nebraska.

3.4.9 Sugar Production in the Twentieth Century and Beyond

In the twentieth century, many former European colonies became independent nations. Today the largest producers of sugar are Brazil, India, China, Thailand, Pakistan, Mexico, the Philippines, and Colombia. Agriculture practices also underwent significant changes; sugar making and various other processes are now automated, with machines replacing manual labor. In most countries, independent farmers grow sugarcane and then sell it to sugar mills. Now sugar is produced everywhere in abundance—200 million tons per year—and is affordable for most people around the world. Nowadays, 70–80 percent of sugar on the market is cane sugar, and about 20–30 percent is beet sugar.

3.5 The Story of Tea

Tea is made from the leaves of Camellia sinensis, a small evergreen tree (ten to twelve feet tall) in the Theaceae family that is native to north Burma and southwestern China (see figure 3.9). Two varieties of the tea plant, C. sinensis var. sinensis and C. s. var. assamica, are cultivated around the world for commercial tea production. The best tea is made from a new bud and the two to three leaves adjacent to it, which are newly formed and delicate and contain the most caffeine. Therefore, Camellia trees are pruned into three-to-four-foot-tall bushes to promote branching and the production of new leaves, as well as to facilitate plucking them. Various processing methods are used to attain different levels of oxidation and produce certain kinds of tea, such as black, white, oolong, green, and pu’erh. Basic processing includes plucking, withering (to wilt and soften the leaves), rolling (to shape the leaves and slow drying), oxidizing, and drying. However, depending on the tea type, some steps are repeated or omitted. For example, green tea is made by withering and rolling leaves at a low heat, and oxidation is skipped; for oolong, rolling and oxidizing are performed repeatedly; and for black, extensive oxidation (fermentation) is employed.

3.5.1 The Discovery of Tea

Tea was discovered in 2700 BCE by the ancient Chinese emperor Shen Nung, who had a keen interest in herbal medicine and introduced the practice of drinking boiled water to prevent stomach ailments. According to legend, once, when the emperor camped in a forest during one of his excursions, his servants set up a pot of boiling water under a tree. A fragrance attracted his attention, and he found that a few dry leaves from the tree had fallen accidentally into the boiling pot and changed the color of the water; this was the source of the aroma. He took a few sips of that water and noticed its stimulative effect instantly. The emperor experimented with the leaves of that tree, now called Camellia sinensis, and thus the drink “cha” came into existence. Initially, it was used as a tonic, but it became a popular beverage around 350 BCE. The historian Lu Yu of the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) has written a poetry book on tea called Cha jing (The Classic of Tea) that contains a detailed description of how to cultivate, process, and brew tea.

Tea spread to Japan and Korea in the seventh century thanks to Buddhist monks, and drinking it became an essential cultural ritual. Formal tea ceremonies soon began. However, tea reached other countries only after the sixteenth century. In 1557, the Portuguese established their first trading center in Macau, and the Dutch soon followed suit. In 1610, some Dutch traders in Macau took tea back to the Dutch royal family as a gift. The royal family took an immediate liking to it. When the Dutch princess Catherine of Braganza married King Charles II of England around 1650, she introduced tea to England. Tea passed from the royal family to the nobles, but for an extended period, it remained unknown and unaffordable to common folks in Europe. The supply of tea in Europe was scant and very costly: one pound of tea was equal to nine months’ wages for a British laborer.

As European trade with China increased, more tea reached Europe, and consumption of tea increased proportionally. For example, in 1680, Britain imported a hundred pounds of tea; however, in 1700, it brought in a million. The British government allowed the British East India Company to monopolize the trade, and by 1785, the company was buying 15 million pounds of tea from China annually and selling it worldwide. Eventually, in the early eighteenth century, tea reached the homes of British commoners.

3.5.2 Tea and the “Opium War”

China was self-sufficient; its people wanted nothing from Europe in exchange for tea. But in Europe, the demand for tea increased rapidly in the mid-eighteenth century. Large quantities were being purchased, and Europeans had to pay in silver and gold. The East India Company was buying so much of it that it caused a crisis for the mercantilist British economy. The company came up with a plan to buy tea in exchange for opium instead of gold and silver. Although opium was banned within China, it was in demand and sold at very high prices on the black market.

After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, several northern provinces in India came under the control of the East India Company, and the company began cultivating poppy in Bengal, Bihar, Orissa, and eastern Uttar Pradesh. Such cultivation was compulsory, and the company also banned farmers from growing grain and built opium factories in Patna and Banaras. The opium was then transported to Calcutta for auction before British ships carried it to the Chinese border. The East India Company also helped set up an extensive network of opium smugglers in China, who then transported opium domestically and sold it on the black market.

After the successful establishment of this smuggling network, British ships bought tea on credit at the port of Canton (now Guangzhou), China, and later paid for it with opium in Calcutta (now Kolkata). The company not only acquired the tea that was so in demand but also started making huge profits from selling opium. This mixed business of opium and tea began to strengthen the British economy and made it easier for the British to become front-runners among the European powers.

By the 1830s, British traders were selling 1,400 tons of opium to China every year, and as a result, a large number of Chinese became opium addicts. The Chinese government began a crackdown on smugglers and further tightened the laws related to opium, and in 1838, it imposed death sentences on opium smugglers. Furthermore, despite immense pressure from the East India Company to allow the open trading of opium, the Chinese emperor would not capitulate. However, that did not curb his subjects’ addiction and the growing demand for opium.

In 1839, by order of the Chinese emperor, a British ship was detained in the port of Canton, and the opium therein was destroyed. The British government asked the Chinese emperor to apologize and demanded compensation; he refused. British retaliated by attacking a number of Chinese ports and coastal cities. China could not compete with Britain’s state-of-the-art weapons, and defeated, China accepted the terms of the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 and the Treaty of Bog in 1843, which opened the ports of Canton, Fujian, and Shanghai, among others, to British merchants and other Europeans. In 1856, another small war broke out between China and Britain, which ended with a treaty that made the sale of opium legal and allowed Christian missionaries to operate in China. But the tension between China and Europe remained. In 1859, the British and French seized Beijing and burned the royal Summer Palace. The subsequent Beijing Convention of 1860 ended China’s sovereignty, and the British gained a monopoly on the tea trade.

3.5.3 The Co-option of Tea and the Establishment of Plantations in European Colonies

Unlike the British, the Dutch, Portuguese, and French had less success in the tea trade. To overcome British domination, the Portuguese planned to develop tea gardens outside China. Camellia is native to China, and it was not found in any other country. There was a law against taking these plants out of the country, and the method for processing tea was also a trade secret. In the mid-eighteenth century, many Europeans smuggled the seeds and plants from China, but they were unable to grow them. Then, in 1750, the Portuguese smuggled the Camellia plants and some trained specialists out of China and succeeded in establishing tea gardens in the mountainous regions of the Azores Islands, which have a climate favorable for tea cultivation. With the help of Chinese laborers and experts, black and green tea were successfully produced in the Portuguese tea plantations. Soon, Portugal and its colonies no longer needed to import tea at all. As the owners of the first tea plantations outside China, the Portuguese remained vigilant in protecting their monopoly. It was some time before other European powers gained the ability to grow and process tea themselves.

In the early nineteenth century, the British began exploring the idea of planting tea saplings in India. In 1824, Robert Bruce, an officer of the British East India Company, came across a variety of tea popular among the Singpho clan of Assam, India. He used this variety to develop the first tea garden in the Chauba area of Assam, and in 1840, the Assam Tea Company began production. This success was instrumental to the establishment of tea estates throughout India and in other British colonies.

In 1848, the East India Company hired Robert Fortune, a plant hunter, to smuggle tea saplings and information about tea processing from China. Fortune was the superintendent of the hothouse department of the British Horticultural Society in Cheswick, London. He had visited China three times before this assignment; the first, in 1843, had been sponsored by the horticultural society, which was interested in acquiring important botanical treasures from China by exploiting the opportunity offered by the 1842 Treaty of Nanking after the First Opium War. Fortune managed to visit the interior of China (where foreigners were forbidden) and also gathered valuable information about the cultivation of important plants, successfully smuggling over 120 plant species into Britain.

In the autumn of 1848, Fortune entered China and traveled for nearly three years while carefully collecting information related to tea cultivation and processing. He noted that black and green teas were made from the leaves of the same plant, Camellia sinensis, except that the former was “fermented” for a longer period. Eventually, Fortune succeeded in smuggling 20,000 saplings of Camellia sinensis to Calcutta, India, in Wardian cases.[4] He also brought trained artisans from China to India. These plants and artisans were transported from Calcutta to Darjeeling, Assam. At Darjeeling, a nursery was set up for the propagation of tea saplings at a large scale, supplying plantlets to all the tea gardens in India, Sri Lanka, and other British colonies.

The British forced the poor tribal population of the Assam, Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa provinces out of their land, and they were sent to work in tea estates. Tamils from the southern province of India were also sent to work in the tea plantation of Sri Lanka. Tea plantations were modeled on the sugar colonies of the Caribbean, and thus the plight of the workers was in some ways similar to that of the slaves from Caribbean plantations.

Samuel Davidson’s Sirocco tea dryer, the first tea-processing machine, was introduced in Sri Lanka in 1877, followed by John Walker’s tea-rolling machine in 1880. These machines were soon adopted by tea estates in India and other British colonies as well. As a result, British tea production increased greatly. By 1888, India became the number-one exporter of tea to Britain, sending the country 86 million pounds of tea.

After India, Sri Lanka became prime ground for tea plantations. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, an outbreak of the fungal pathogen Hemilia vastatrix, a causal agent of rust, resulted in the destruction of the coffee plantations in Sri Lanka. The British owners of those estates quickly opted to plant tea instead, and a decade later, tea plantations covered nearly 400,000 acres of land in Sri Lanka. By 1927, Sri Lanka alone produced 100,000 tons per year. All this tea was for export. Within the British Empire, fermented black tea was produced, for which Assam, Ceylon, and Darjeeling tea are still famous. Black tea produced in India and Sri Lanka was considered of lesser quality than Chinese tea, but it was very cheap and easily became popular in Asian and African countries. In addition to India and Ceylon, British planters introduced tea plantations to fifty other countries.

3.6 The Story of Coffee

Coffee is made from the roasted seeds of the coffee plant, a shrub belonging to the Rubiaceae family of flowering plants. There are over 120 species in the genus Coffea, and all are of tropical African origin. Only Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora are used for making coffee. Coffea arabica (figure 3.10) is preferred for its sweeter taste and is the source of 60–80 percent of the world’s coffee. It is an allotetraploid species that resulted from hybridization between the diploids Coffea canephora and Coffea eugenioides. In the wild, coffee plants grow between thirty and forty feet tall and produce berries throughout the year. A coffee berry usually contains two seeds (a.k.a. beans). Coffee berries are nonclimacteric fruits, which ripen slowly on the plant itself (and unlike apples, bananas, mangoes, etc., their ripening cannot be induced after harvest by ethylene). Thus ripe berries, known as “cherries,” are picked every other week as they naturally ripen. To facilitate the manual picking of cherries, plants are pruned to a height of three to four feet. Pruning coffee plants is also essential to maximizing coffee production to maintain the correct balance of leaf to fruit, prevent overbearing, stimulate root growth, and effectively deter pests.

Coffee is also a stimulative, and the secret of this elixir is the caffeine present in high quantities in its fruits and seeds. In its normal state, when our bodies are exhausted, there is an increase in adenosine molecules. The adenosine molecules bind to adenosine receptors in our brains, resulting in the transduction of sleep signals. The structure of caffeine is similar to that of adenosine, so when it reaches a weary brain, caffeine can also bind to the adenosine receptor and block adenosine molecules from accessing it, thus disrupting sleep signals.

3.6.1 The History of Coffee

Coffea arabica is native to Ethiopia. The people of Ethiopia first recognized the stimulative properties of coffee in the ninth century. According to legend, one day, a shepherd named Kaldi, who hailed from a small village in the highlands of Ethiopia, saw his goats dancing energetically after eating berries from a wild bush. Out of curiosity, he ate a few berries and felt refreshed. Kaldi took some berries back to the village to share, and the people there enjoyed them too. Hence the local custom of eating raw coffee berries began. There are records that coffee berries were often found in the pockets of slaves brought to the port of Mokha from the highlands of Ethiopia. Later, the people of Ethiopia started mixing ground berries with butter and herbs to make balls.

The coffee we drink today was first brewed in Yemen in the thirteenth century. It became popular among Yemen’s clerics and Sufis, who routinely held religious and philosophical discussions late into the night; coffee rescued them from sleep and exhaustion. Gradually, coffee became popular, and coffeehouses opened up all over Arabia, where travelers, artists, poets, and common folks visited and had a chance to gossip and debate on a variety of topics, including politics. Often, governments shut down coffeehouses for fear of political unrest and revolution. Between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, coffeehouses were banned several times in many Arab countries, including Turkey, Mecca, and Egypt. But coffeehouses always opened again, and coffee became ingrained in Arab culture.

Arabs developed many methods of processing coffee beans. Usually, these methods included drying coffee cherries to separate the beans. Dried coffee beans can be stored for many years. Larger and heavier beans are considered better. The taste and aroma develop during roasting, which determines the quality and price of the coffee. Dried coffee beans are dark green, but roasting them at a controlled temperature causes a slow transformation. First, they turn yellow, then light brown, while also popping up and doubling in size. After continued roasting, all the water inside them dries up, and the beans turn black like charcoal. The starch inside the beans first turns into sugar, and then sugar turns into caramel, at which point many aromatic compounds come out of the cells of the beans. Roasting coffee beans is an art, and a skilled roaster is a very important part of the coffee trade.

3.6.2 The Spread of Coffee out of Arabia

Coffee was introduced to Europeans in the seventeenth century, when trade between the Ottoman Empire and Europe increased. In 1669, Turkish ambassador Suleiman Agha (Müteferrika Süleyman Ağa) arrived in the court of Louis XIV with many valuable gifts, including coffee. The French subsequently became obsessed with the sophisticated etiquettes of the Ottoman Empire. In the company of Aga, the royal court and other elites of Parisian society indulged in drinking coffee. Aga held extravagant coffee ceremonies at his residence in Paris, where waiters dressed in Ottoman costumes served coffee to Parisian society women. Suleiman’s visit piqued French elites’ interest in Turquerie and Orientalism, which became fashionable. In the history of France, 1669 is thought of as the year of “Turkmenia.”

A decade later, coffee reached Vienna, when Turkey was defeated in the Battle of 1683. After the victory, the Viennese seized the goods left behind by the Turkish soldiers, including several thousand sacks of coffee beans. The soldiers of Vienna didn’t know what it was and simply discarded it, but one man, Kolshitsky, snatched it up. Kolshitsky knew how to make coffee, and he opened the first coffeehouse in Vienna with the spoils.

By the end of the seventeenth century, coffeehouses had become common in all the main cities of Europe. In London alone, by 1715, there were more than 2,000 coffeehouses. As in Arabia, the coffeehouses of Europe also became the bases of sociopolitical debates and were known as “penny universities.”

3.6.3 Coffee Plantations

By the fifteenth century, demand for coffee had increased so much that the harvest of berries from the wild was not enough, and thus in Yemen, people began to plant coffee. Following Yemen’s lead, other Arab countries also started coffee plantations. Until the seventeenth century, coffee was cultivated only within North African and Arab countries. Arabs were very protective of their monopoly on the coffee trade. The cultivation of coffee and the processing of seeds was a mystery to the world outside of Arabia. Foreigners were not allowed to visit coffee farms, and only roasted coffee beans (incapable of producing new plants) were exported. Around 1600, Baba Budan, a Sufi who was on the Haj pilgrimage, successfully smuggled seven coffee seeds into India and started a small coffee nursery in Mysore. The early coffee plantations of South India used propagations of plants from Budan’s garden.

In 1616, a Dutch spy also succeeded in stealing coffee beans from Arabia, and these were used by the Dutch East India Company as starters for coffee plantations in Java, Sumatra, Bali, Sri Lanka, Timur, and Suriname (Dutch Guiana). In 1706, a coffee plant from Java was brought to the botanic gardens of Amsterdam, and from there, its offspring reached Jardin de plantes in Paris. A clone of the Parisian plant was sent to the French colony Martinique, and then its offspring spread to the French colonies in the Caribbean, South America, and Africa. In 1728, a Portuguese officer from Dutch Guiana brought coffee seeds to Brazil, which served as starters for the coffee plantations there. The Portuguese also introduced coffee to African countries and Indonesia, and the British established plantations in their Caribbean colonies, India, and Sri Lanka from Dutch stock.

In summary, all European coffee plants came from the same Arabian mother plant. So the biodiversity within their coffee plantations was almost zero, which had devastating consequences. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the fungal pathogen Haemilia vestatrix severely infected coffee plantations in Sri Lanka, India, Java, Sumatra, and Malaysia. As a result, rust disease destroyed the coffee plantations one by one. Later, in some of the coffee plantations, Coffea canephora (syn. Coffea robusta), which has a natural resistance to rust, was planted, but others were converted into tea plantations (as in the case of Sri Lanka, discussed earlier).

European coffee plantations used the same model as tea or sugar plantations, and so their workers lived under the same conditions. European powers forcefully employed the poor native population in these plantations and used indentured laborers as needed. For example, in Sri Lanka, the Sinhalese population refused to work in the coffee farms, so British planters recruited 100,000 indentured Tamil workers from India to work the farms and tea plantations there.

3.7 The Heritage of Plantations

In the twentieth century, most former European colonies became independent countries. In these countries, private, cooperative, or semigovernmental institutions manage plantations of sugarcane, tea, coffee, or other commercial crops. Though these plantations remain a significant source of revenue and contribute significantly to the national GDP of many countries, their workers still often operate under abject conditions.

References

Johannessen, C. L., & Sorenson, J. L. (2009). World trade and biological exchanges before 1492. iUniverse. (↵ Return)

Further Readings

Aronson, M., & Budhos, M. (2010). Sugar changed the world: A story of magic, spice, slavery, freedom, and science (1st ed.). Clarion.

Bahadur, G. (2014). Coolie woman: The odyssey of indenture. University of Chicago Press.

Clarkson, T. (1785). An essay on the slavery and commerce of the human species. http://abolition.e2bn.org/source_16.html

Galloway, J. H. (1989). The sugar cane industry: An historical geography from its origins to 1914. Cambridge University Press.

Gandhi, M. K. (1972). Satyagraha in South Africa. Navajivan. (Original work published 1924)

Linares, O. F. (2002). African rice (Oryza glaberrima): History and future potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 16360–65. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.252604599

Pendergrast, M. (2010). Uncommon grounds: The history of coffee and how it transformed our world. Basic Books.

Rose, S. (2011). For all the tea in China: How England stole the world’s favorite drink and changed history. Penguin.

Tinker, H. (1974). New system of slavery the export of Indian labor overseas 1830–1920 (Institute of Race Relations). Oxford University Press.

YouTube documentary “Black Coffee: The Irresistible Bean.”

Part 1—https://youtu.be/XbrF1CmaUDo

Part 2—https://youtu.be/bwsyktsWmhE

Part 3—https://youtu.be/a_tWx8-7wB4

- As an example, Ẓahīr al-Dīn Muḥammad Bābur(1483–1530), the founder of the Mughal dynasty, invaded Hindustan (northern India) and established his capital in the city of Agra. His artisans and well-versed gardeners for the first time introduced several crops of Central Asia into India: on the banks of the Yamuna River in the city of Agra, India, they sowed watermelons, melons, musk melon, and so on and planted grapes and roses in the Agra Fort. ↵

- The Arthaśāstrais is an ancient Indian text on politics, economic policy, and military strategy written in Sanskrit by Kauṭilya, also known as Vishnugupta or Chanakya. He was a scholar at the ancient school Takshashila and the teacher and guardian of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire in northern India. ↵

- See the history of the abolitionist movement and related documents at http://abolition.e2bn.org. ↵

- The Wardian case, a precursor to the modern terrarium, was a special type of sealed glass box made by British doctor Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward in 1829. The delicate plants within them could thrive for months. Plant hunter Joseph Hooker successfully used Wardian cases to bring some plants from the Antarctic to England. In 1933, Nathaniel Ward also succeeded in sending hundreds of small ornamental plants from England to Australia in these boxes. After two years, another voyage carried many Australian plants back to Dr. Ward as a gift. Despite lengthy and difficult journeys, these plants survived, and so Wardian cases proved extremely useful for plant hunters, such as Robert Fortune. ↵