The Origins of Agriculture

1.1 Hunter-Gatherers

Before the agricultural revolution (10,000–12,000 years ago), hunting and gathering was, universally, our species’ way of life. It sustained humanity in a multitude of environments for 200,000 years—95 percent of human history. Why did our ancestors abandon their traditional way of life to pursue agriculture?

For a long time, scientists, including Charles Darwin, assumed that primitive humans invented agriculture by chance, and once the secret was discovered, the transition toward agriculture was inevitable. However, this is only possible if we assume that (i) the biggest obstacle to the adoption of agriculture was a lack of knowledge about plants’ life cycles and propagation and (ii) farming was easier than hunting and gathering from its beginnings. We can’t verify or refute these hypotheses directly. However, studies of materials (e.g., tools made of stones and bones, fossilized seeds, rock paintings, and engravings) found in many archaeological excavations, as well as anthropological studies on present-day hunters and gatherers—who still live in various corners of the world—have contributed much to our understanding of the early history of agriculture.

Scholars’ interest in the contemporary hunters and gatherers was rekindled after the 1966 Man the Hunter conference, organized by Irven DeVore and Richard Lee in Chicago. Richard Lee, a PhD student studying under DeVore, had lived in Botswana with the !Kung, one of the San (Bushman) clans of Kalahari Desert, for three years (1963–1965). He shared his experience at the conference and reported !Kung men hunt and !Kung women gather. He added, “Although hunting involves a great deal of effort and prestige, plant foods provide from 60–80 per cent of the annual diet by weight. Meat has come to be regarded as a special treat; when available, it is welcomed as a break from the routine of vegetable foods, but it is never depended upon as a staple” (1). He further added that the !Kung had a more than adequate diet achieved by a subsistence work effort of only two or three days per week, a far lower level than that required of wage workers in our own industrial society, and working adults easily take responsibility for children, old people, and the disabled. In these groups, starvation, malnutrition, and crime are nil. He argued that the social lives of the people of the Bushmen clans are more dignified than that of civilized society and concluded, “First, life in the state of nature is not necessarily nasty, brutish, and short” (1).

American anthropologist Marshall Sahlins agreed with Richard Lee, stating that Australia’s indigenous people also have substantial resources when compared to the common man of industrial society and work fewer hours per day, with more time for leisure. He explained that the hunter-gatherers consume less energy per capita per year than any other group of human beings, and yet all the people’s material wants were easily satisfied. Sahlins further adds, “Hunters and gatherers work less than we do, and rather than a grind the food quest is intermittent, leisure is abundant, and there is a more sleep in the daytime per capita than in any other condition of society” (2).

The prevailing belief till then was that in comparison to civilized societies, the hunters and gatherers were impoverished: their way of life precarious, full of hardship, and the life of people in such a state of nature, short and brutish. When the proceedings of this conference were published in 1968, such prejudices were refuted and put to rest, rousing a new interest in researchers worldwide to study contemporary hunters and gatherers.

Over the past fifty years, anthropologists, archeologists, biologists, botanists, demographers, and linguists have studied various tribes of contemporary hunter-gatherers. These studies suggest that hunter-gatherers possess tremendous knowledge about the flora and fauna present in their surroundings. They can identify edible plants from a sea of wild vegetation and know which plants’ parts can be eaten raw and which need cooking or further processing. In their memories, they retain a seasonal calendar: they know when new plants sprout, bloom, and are ready for harvest or when animals and birds breed. They extract medicines, drugs, intoxicants, and poisons from various plants and make fibers for clothing, baskets, and other objects. The marks of seasonal variations and their specific geographical surroundings are visible in their diets. For example, people living in Arctic regions are entirely carnivorous; the Hadza of Tanzania are predominantly vegetarians; and the !Kung San of the Kalahari Desert in South Africa are omnivores. Regardless of their locale, hunters and gatherers consume ~500 varieties of food throughout the year and make the best possible use of the resources available to them. In comparison, today’s rich urban folks hardly sample food items from fifty unique sources.

It has also been observed that most hunter-gatherers care about their environment. They do not hunt without need, waste less, and play active roles in managing their resources. For example, natives living in different parts of the world set forest fires at fixed intervals to manage the landscape. Such controlled fires help eliminate weeds and insects and promote the germination of seeds that are enclosed within hard shells (e.g., pinenuts, chestnuts, and walnuts), thus deliberately increasing the number of seed-producing plants for them to eat. Afterward, when the fire is extinguished, grass grows on the ground, and herbivores are attracted to these pastures for several months, thereby making hunting easy. Such multilevel environmental management is just one example of how these people use their knowledge of the natural world to survive outside of agricultural society.

Many foragers are also aware of how to produce food and occasionally do so in hours of need. For example, New Guinea tribes weed and prune the Sago palms that grow in the forest to increase their yield. The natives of northern Australia bury the tips of taro and eddoes into the ground to propagate new plants and channel rainwater to plains where many wild grasses grow. Subsequently, they harvest tubers and seeds for their consumption.

It is not very difficult to comprehend that compared to foraging, farming is labor-intensive and requires substantial planning to sow, weed, harvest, process, and store crops. Farming must have been a very difficult task in prehistoric times, and crop failures would have been prevalent. Thus as long as needs were fulfilled by hunting and gathering, people likely did not pursue farming despite having the knowledge required for plant propagation. For centuries, humans were sustained instead by a mixed strategy that included hunting, fishing, foraging, and some farming. When resources from the wild were plentiful, farming was abandoned. It was thousands of years before human societies began to completely rely on agriculture. The growth of agriculture was not linear but rather erratic; its adoption was not a coincidence but a slow pursuit full of trials and errors.

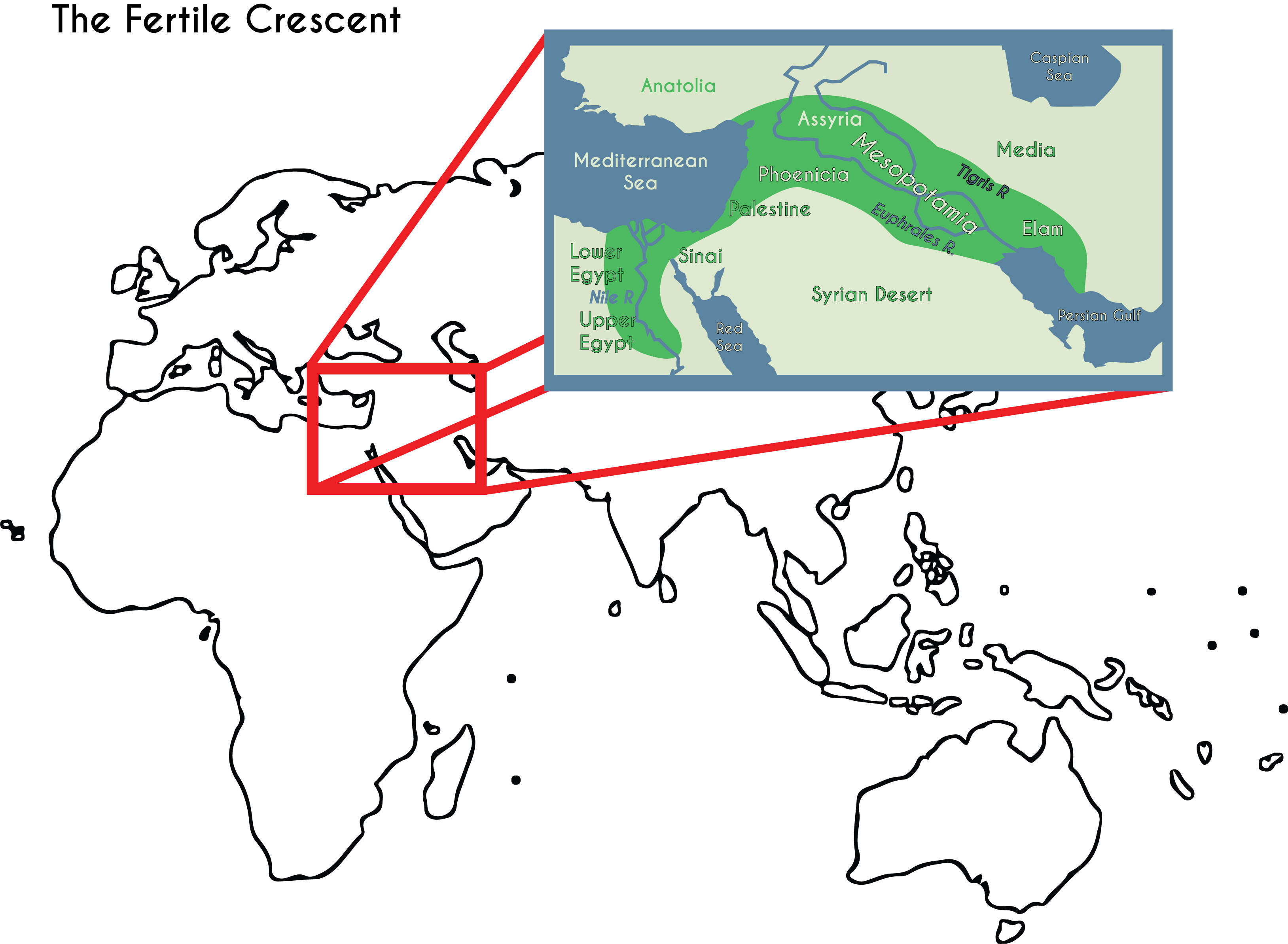

Archaeological evidence suggests that nomadic human tribes began farming during the Neolithic period, and so it is often referred to as the Neolithic Revolution. About 12,000 years ago, one of the first attempts at farming began in the Fertile Crescent, the Levant region of the Near East that includes the interior areas of present-day Turkey, Israel, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, Turkmenistan, and Asia Minor. The ancient inhabitants of the Fertile Crescent, known as Natufians, gathered wild wheat, barley, lentils, almonds, and so on and hunted cattle, gazelle, deer, horses, and wild boars (see figure 1.1).

Throughout this region, thousands of archeological excavations have been conducted and numerous objects—including grinding stones, flint, bone tools, stone sickles, dentalium, shell ornaments, and many fine tools of polished stone—have been unearthed. These show that prior to the adoption of agriculture, the inhabitants of this region had already acquired knowledge about their surrounding vegetation and used tools for cutting, uprooting, and harvesting wild plants, which could have made their transition toward farming easier. The direct descendants of the Natufians, the prepottery Neolithic people, successfully domesticated more than 150 crops, including barley, wheat, pulses, and so on. They also domesticated animals and built the first villages in human history.

Numerous discoveries in recent years indicate that besides the Fertile Crescent, parallel efforts of cultivation began in several other parts of the world. For example, 9,000 years ago, in China’s Yellow River valley, rice cultivation began; 5,000 to 8,000 years ago, in Africa and East Asia, the cultivation of a variety of roots and tubers was underway; and 7,000 to 9,000 years ago, people in South America were growing maize, beans, and squash. Hence the history of agriculture is only 12,000 years old, and it spread around the globe relatively quickly. But how did geographically isolated human groups, unaware of one another’s existence, begin farming within this short period of time, ditching the hunter-gatherer way of life?

1.2 Why Agriculture?

Australian archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe first linked the beginning of agriculture to climate change. He suggests that at the end of the last ice age (6,000–13,000 years ago), the earth’s average temperature increased and glaciers moved rapidly northward. Additionally, rainfall progressively decreased in Southwest Asia and Africa; thus year after year, this region suffered spells of drought that caused the loss of vegetation and several animal species. Over a prolonged period, the rainforests turned into savannas, where herbivores dwelled only for a few months. Under the changed circumstances, humans were unable to sustain themselves throughout the year by hunting and foraging. The human groups, living on different continents and unaware of one another’s existence, were forced to produce their own food, and farming began within a short span of time all around the globe.

The transition toward farming was not easy. It was not a eureka moment; agriculture was adopted under unpleasant circumstances and the obligation to produce food was indeed a farewell to the heaven for mankind. Consider the story of Eve, who, under the influence of a snake, plucks the forbidden fruit and eats it with Adam; as a consequence, they acquire wisdom and develop a sense of good and evil. The Lord God becomes angry, and as a punishment, Adam and Eve are banished from the Garden of Eden to work the ground and grow their own food to survive. To Adam, God says,

Because you listened to your wife and ate fruit from the tree about which I commanded you, “You must not eat from it,”

Cursed is the ground because of you;

through painful toil you will eat food from it

all the days of your life.

It will produce thorns and thistles for you,

and you will eat the plants of the field.

By the sweat of your brow

you will eat your food

until you return to the ground,

since from it you were taken;

for dust you are

and to dust you will return.[1]

Farming was not fun. It required tremendous effort and the capacity to endure hardship.

1.3 A Women’s Enterprise

It is believed that agriculture was invented by women. The women of the preagrarian societies collected wild fruits, berries, tubers, and roots and had generational experience in identifying edible plants and knowledge about plants’ life cycles and how they grow. It has been suggested that women’s extraordinary vision, more developed motor skills, and ability to process finer details evolved due to the importance of their involvement in foraging activities for millions of years. For example, the average woman’s eyes can distinguish about 250 shades and hues, while an average man’s can only see 40–50.

When droughts became regular, the tribes of our ancestors made temporary encampments along the lakes and ponds where men ambushed animals who came to quench their thirst. Their foraging experience helped womenfolk take the initiative in growing food. They sowed the seeds of wild grasses in the surrounding marshes and planted parts of the tubers to propagate new plants.

In most traditional societies, even today, this historical association of women in agriculture is revered: often, women sow the first seeds to bestow good luck for a bountiful harvest. Invariably, across all cultures, we find a similar feminine influence in stories related to the origin of farming. For example, in ancient Egypt, Isis was deemed the goddess of agriculture: Once upon a time, a severe drought caused a widespread famine on the earth. There was nothing to eat, and cannibalism began. In such a situation, the goddess Isis offered barley and wheat from the wild to the starving people, and taught them how to produce their own food. Thus farming saved mankind from starvation.

In Greek mythology, Demeter was the goddess of fertility and the harvest. After every harvest, the first loaf of bread was offered to her as a sacrifice. She was called Ceres by the Romans, and thus grains were called “cereal.” The legend of Demeter contains an interesting tale about the origin of agriculture. According to this myth,

with the blessing of Demeter, the earth was always filled with grains, berries, and fruits. Humans took their share of this bounty and survived happily for a long time. But it came to a sudden end when Hades, the god of the underworld, abducted Demeter’s lovely daughter Persephone. Persephone was Demeter’s only child and the center of all her attention and devotion. Demeter desperately searched everywhere for her daughter, but it was to no avail. She fell into depression, and transformed into an ugly old woman and became unrecognizable. She encountered abuse and ill-treatment from everyone around. Only, Celeus, the king of Eleusis, warmly welcomed her. While she continued her search for Persephone, she ignored her responsibility of making the earth fertile. Her despair had an effect on the crops; famines were prevalent and people starved. Eventually, the gods intervened and plead with Demeter to bless the earth with a good harvest, and in exchange, they forced Hades to free Persephone. However, before releasing Persephone, Hades fed her pomegranate seeds (the food of the underworld) that bound her to the underworld forever. When the gods asked Persephone to choose where she wanted to live, she wished to remain in the underworld. As a result, Demeter was devastated. Finally, Zeus intervened and came up with a compromise that allowed Persephone to spend six months per year on the earth with Demeter and six with Hades in the underworld. When Persephone visits her mother from spring to summer, the earth is full of flowers and fruits, crops grow, and harvests are bountiful. When Persephone heads back underground, Demeter falls into a depressed state, resulting in autumn and winter. Demeter did not get her daughter fully back, so, she did not restore earth’s fertility completely. However, in return for the kindness of King Celeus, she taught his son Triptolemus the art of agriculture for survival, and he later taught it to mankind.

In Mexico, Hispaniola, and Latin America (the sites of the great Mayan and Aztec civilizations), we find stories about the origin of man and corn. For example,

Man is born from maize; maize is the mother of man.

When the gods created man, the Holy Spirits chanted for his well-being and finally maize emerged from the breasts of the mother Earth to sustain humans.

Mother Earth gifted her five daughters—white, red, yellow, spiked, and blue maize—to man.

Similarly, Hindu mythology has several goddesses, including Bhudevi (the earth goddess), Annapurna (the goddess of grains, who provides nutrition to everyone), and Shakti (the creator of the entire plethora of vegetation). According to the legend of Annapurna,

Once, the Lord Shiva (who represents the male power, the Purush) and his wife Parvati (the creator of nature, a.k.a. Prakriti or Shakti) argued about who was superior between the two and the discussion quickly ended on a sour note. Shiva stressed the superiority of Purush (male) over Prakriti (Mother Nature). Enraged, Parvati deserted her husband and disappeared, which resulted in a widespread famine. Shiva’s followers, who were starving, asked for his help. Shiva took a begging bowl, and his band followed him. They went from door to door, but the people themselves had nothing to eat, so they turned the beggars away. Shiva’s band learned about a charity kitchen in the city of Kashi (also known as Varanasi) that was feeding everyone and decided to visit Kashi. To their surprise, Parvati owned that kitchen, and she had become the goddess Annapurna, wearing celestial purple and brown, and was serving food to the starving gods and mankind. Upon Shiva’s turn, she likewise offered food to him and his followers. Shiva realized that the existence of humanity depends on nature; the brute force of male power is not enough to sustain life on Earth.

The common thread of all these myths is the appearance of the savior female deity who taught mankind to cultivate grains to survive. Although these myths have no literal value, they serve as metaphors or narratives of human experiences and survived through generational memories. They are also, in fact, consistent with the climate change theory of the origin of agriculture.

1.4 Slash and Burn: Shifting Cultivation

At the dawn of agriculture, the primitive people of the Neolithic era only had some tools made of stones and animal bones at their disposal. These tools were useless for such a monumental task as embarking on the path to farming. Fortunately, mankind’s knowledge and experience of taming fire came in handy. Long before the origins of modern humans, Homo erectus, an ancestor of the hominid branch, had learned to light and control fire. Afterward, the members of genus Homo moved northwards from Africa and survived the cold weather of Europe and Asia with the help of this skill. Humans used their best weapon, fire, to create the first farms. First, they slashed the vegetation, then burned it to clear the small patches in the forests, and finally, sowed seeds in the ashes. This practice of farming, known as slash-and-burn agriculture, still survives in the Amazon rainforests and in many mountainous regions of the world. The plots created by this method are very fertile initially, but with each passing year, they are overtaken by more and more weeds, pests, and parasites, which causes a decline in their fertility. So after three to four years, the people move to another site. Thus this practice is also known as “shifting cultivation” or “swidden agriculture.” In India, it is known as “jhoom” among the native Adivasi tribes (descended from an ancient forest-dwelling people). After people abandon a site, in the fallow field, grass and weeds grow, and it serves as a pasture for herbivores and hunting grounds. Slowly, the fertility of these pastures returns, shrubs and trees grow, and they become part of the forest again. In this way, the field, fallow land, and the surrounding forest are recycled. Also, weeds, insects, and other parasites are kept in balance.

Today, we are farming with highly sophisticated machines and have specialized tools for various tasks, from sowing to harvesting, and yet farming is still a tremendous task. We cannot even grasp how difficult it would have been in prehistoric times. For thousands of years, generations of mankind struggled to make farming productive. They also continued to gather and hunt to make up for the shortfall or crop failures. Since farming required much more time and effort, farming would have been abandoned from time to time if nature was bountiful. It has been suggested by various studies that agriculture did not progress smoothly; it took several thousand years before humanity could fully rely on agriculture.

So to summarize, the history of agriculture is 12,000 years old, and traces back to a time when changes in the earth’s global climate led to widespread drought and a decline in natural resources, forcing our ancestors to produce their own food. For thousands of years, shifting cultivation supplemented their diets while hunting and gathering remained the main source of sustenance. The discovery of agriculture was not an accident but the product of trial and error as well as improvisation that spanned many centuries, a process that still continues today.

Animal husbandry is considered a by-product of agriculture. It has been suggested that during droughts, people survived on stored grains, and they used some grains to feed herbivores to keep them around for easy hunting. The credit to domesticating animals primarily goes to men.

1.5 The Emergence of the First Agricultural Societies

Even though agriculture started almost simultaneously in many regions of the world, its progress was not uniform. The biodiversity of various geographical regions (e.g., their flora, animals, birds, insects, and microorganisms) influenced the emergence of stable agricultural societies. In some areas of the tropics, particularly in Africa, people had great success in growing tubers like yams, potatoes, eddoe, sweet potatoes, and cassava. These plants can be propagated by burying a small part of the tuber in the ground and so did not require an understanding of the plant’s life cycle. So these groups had an easy head start thanks to vegetative propagation that produced identical plants (clones), which did not differ significantly in yield. They learned to process many types of tubers and invented a very complex process of separating cyanide and starch from cassava to make starchy tapioca pearls. These undertakings helped folks sustain themselves year-round, but did not accumulate enough surplus to free a section of the population from farming, allowing them to pursue other tasks needed for the further advancement of their societies.

In South and Central America, maize was the mainstay of civilization. However, the natural structure of maize plants promotes outcrossing: on this plant, male flowers, known as tassels, hang from the tip, whereas the female flowers (silk) grow on the stem. Maize pollens are very lightweight and reach the female flowers via wind. Thus male flowers can pollinate female flowers of the same plant (self-pollination) or of another plant (cross-pollination). Although in maize, the chances of self-pollination and cross-pollination events are equal, the progeny born of selfing is inferior (gives lower yield) compared to the progeny born of outcrossing. Thus farmers need to plant different varieties of maize in the same fields to ensure maximum yield. In the absence of this knowledge, the productivity of the crop cannot be assured from one year to another. Only after such an understanding developed could people rely fully on maize farming and utilize the surplus to build the great civilizations of the Aztecs and Mayans.

In the Fertile Crescent, about thirty-two species of grass—including the wild species of wheat, barley, sorghum, millet, and oats—grow naturally. Incidentally, most grasses have complete flowers with both male and female organs, and self-pollination rules over cross-pollination. As a result, the characteristics of grasses remain stable, and crop yields do not vary from one year to another. If the plants with large grains are picked and carried forward, then crops with large seeds can be harvested for generations. Additionally, the grass seeds can be stored for a very long period of time and year-round dependence on these grains was easily established. So the early farmers of this region benefitted from growing grasses.

In the Fertile Crescent, animal husbandry began in parallel with farming. Some groups exclusively pursued this path and so developed a nomadic way of life. They moved with their herds following the availability of grazing grounds and trading the products of one farming community with another. These pastoralists thus further strengthened the stability of farming communities and broadened the region’s resource base. Such advances helped the people of the Fertile Crescent settle in one place permanently and establish the first villages.

In China, along the Yellow River, people learned to cultivate rice. Rice is also a self-pollinated grass, and so these early farmers could rely on its harvest for yearlong sustenance and could store surplus seeds. Unlike their contemporaries in the Fertile Crescent, Chinese farmers could harvest two crops of rice per year and so their surplus grew even more rapidly. So they reaped similar advantages and almost simultaneously established permanent settlements.

About 5,500 years ago, an independent initiative of paddy cultivation was undertaken in the Indo-Gangetic plains that are spread across South Asia. In addition to rice, the peoples of South Asia and East Asia independently learned to grow a variety of minor grains, pulses, vegetables, fruits, tubers, roots, and oilseed crops.

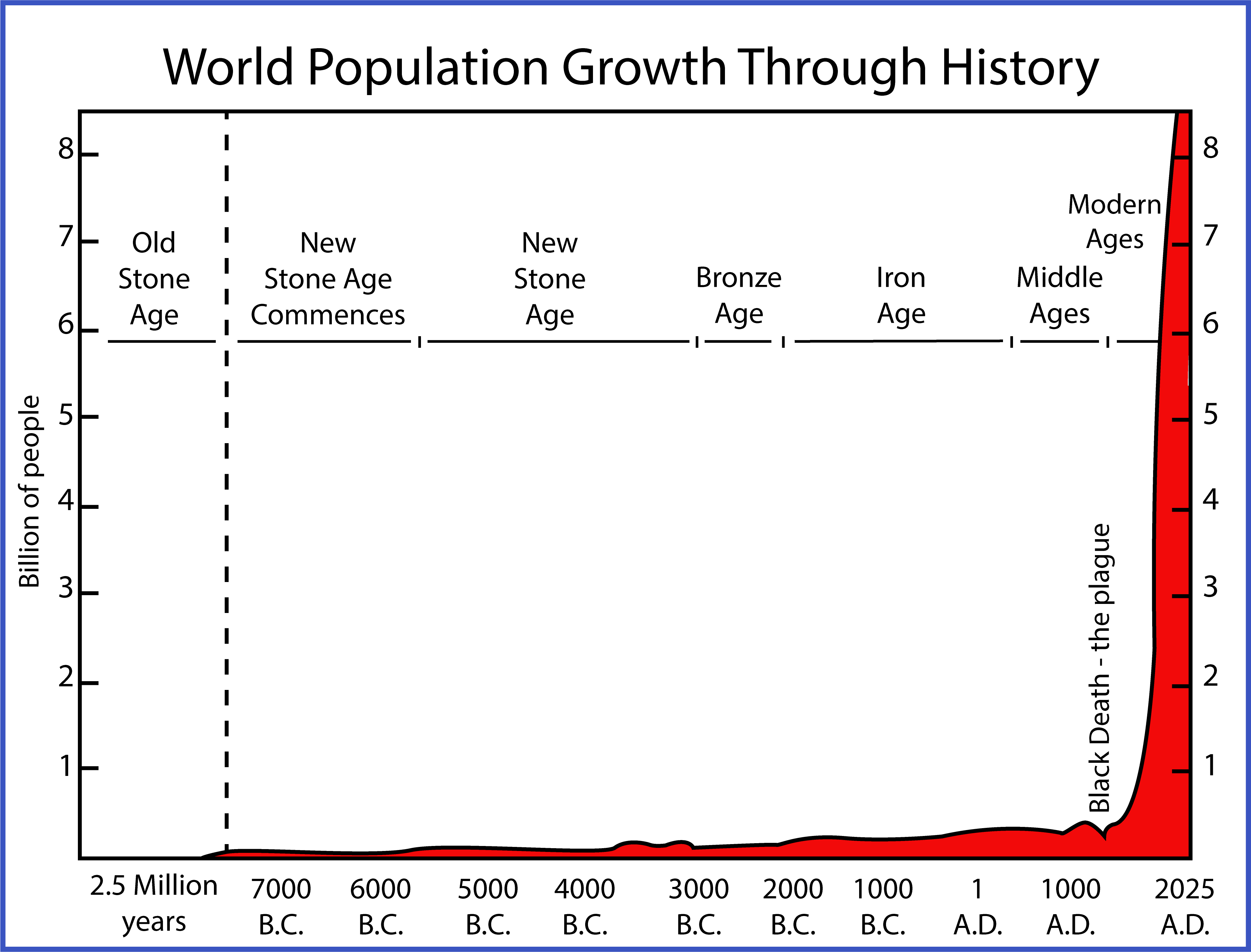

As agriculture progressed, many river-valley civilizations—in the Indus Valley, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China—came into existence. Meanwhile, the populations of hunter-gatherers remained more or less stable. As agriculture developed and productivity increased, the human population grew proportionally (see figure 1.2). The first minor jump occurred after the discovery of metals that made many more tools like plows, available to farmers. The use of a plow powered by domesticated animals resulted in a significant increase in food production. In this way, 5,000 years ago, farming began to seem like a better alternative to the hunter-gatherer’s way of life. The surplus grain freed a large section of the population from farming and allowed them to invest energy in other tasks that led to the second major change—the division of labor in human society. Subsequently, the collective sharing of resources was replaced with individual ownership—private property—which gave rise to a need to ensure the succession of one’s own bloodline. As a consequence, rules of strict sexual conduct for women were formulated and, like infields and domesticated animals, they became the property of men. As class divisions deepened, the unit of a family, headed by a patriarch, strengthened. Soon, tribes headed by patriarchs began to fight for control over their possessions and to expanding their domains, which gave rise to more complex and organized social and political structures, like states, nations, and religion. In societies dependent on subsistence agriculture—where property has not developed and most of the people remain engaged in agriculture—complex social structures, division of labor, crime, patriarchy, and other sociopolitical structures are also poorly developed.

Agriculture transformed human society, but this transformation also, in turn, influenced agricultural practices. While the family, private property, and various institutions were born as by-products of agriculture, these sociopolitical advancements also impacted agriculture. To this day, agriculture continues to be highly entangled with society and human history. In the following chapters, we will review the historical progress of agriculture, advancements in science and technology that influenced farming, and the impact of agriculture on humanity.

References

1. Lee, R. B. (1968). What hunters do for a living, or, how to make out on scarce resources. In R. B. Lee and I. DeVore (Eds.), Man the hunter (pp. 40, 43). Aldine. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

2. Sahlins, M. (1968). Notes on the original affluent society. In R. B. Lee and I. DeVore (Eds.), Man the hunter (pp. 85, 86). Aldine. (↵ Return)

Further Readings

Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societies. W. W. Norton.

Lee, R. B. (1979). The !Kung San: Men, women and work in a foraging society. Cambridge University Press.

- From Genesis 4:23, from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. ↵