Women, War, and Peace

Amanda Milburn

War is a violent and destructive force. The historiography of war has traditionally focused on its military aspects and has therefore concerned itself predominantly with men. Such an approach masks both the gendered nature of warfare and its wide-ranging impact. This chapter explores the ways in which war and militarization affect women around the world. It will examine the patriarchal systems built and perpetuated during and after conflict and consider the extent to which women are able to exhibit agency within the confines of these systems. It concludes with a discussion of women’s participation in peace and justice movements.

Gendering War

Men and women experience war differently. Even so, the study of conflict has historically ignored gender as a category of analysis, and even when gender is acknowledged, patriarchal discourse often remains. The pervasive assumption that domestic life is the realm of women and public life the purview of men belies the complex lived experiences of women. Feminist scholarship shows us a far more nuanced situation. The impact of war on women is not binary. War has disproportionately negative effects on women, especially those who exist within multiple categories of oppression. Militaries are masculine institutions and perpetuate patriarchal power relationships. Nevertheless, women do engage in the process of war-making. Conflict can redefine gender roles in a way that can offer opportunities to women, though these are frequently short-term rather than lasting changes. Postwar reconstruction often sees a resurgence of patriarchal systems and regimes.

The Dahomey Women Warriors of West Africa

by Andi Boyer

Although fighting in war has been reserved as a male role through much of history in western culture, in the 1700s and 1800s women in the Republic of Benin in West Africa (then called the Kingdom of Dahomey) were a formidable army. At that time called Mino (“our mothers”), they are currently referred to as the “Dahomey Amazons.” The Dahomey Amazon Army was composed of single women who voluntarily (by enrolling) and involuntarily (taken from among slaves or forced to enroll by male family members) became members of the militia. These warrioresses earned praises both from within their ranks as well as from their enemies. A French Foreign Legionnaire named Bern lauded them as “warrioresses . . . fight with extreme valor, always ahead of the other troops. They are outstandingly brave. . . well trained for combat and very disciplined.”

In their own culture, they were highly celebrated and given lavish goods such as tobacco, alcohol, and slaves, but they were also required to remain single and without children, or any part in a family life. Throughout the eighteenth century, the Dahomey Amazons grew from six hundred warriors to more than six thousand (between 30 and 40 percent of the army) before the French government defeated them in the nineteenth century. The Dahomey Amazons were known as Huntresses, riflewomen, reapers, archers, and, later, gunners. The Dahomey Amazons lived by the motto “If soldiers go to war, they should conquer or die.”

Women’s Participation in War

Women actively participate in war in multiple complex and competing roles. Camp followers, civilians who travel with the military, provide informal yet essential services necessary for armies to function. The presence of women camp followers has been recorded from the Middle Ages onward, and their importance during the American Revolution (1765-83) has been particularly well documented, with war records indicating one woman camp follower for every fifteen revolutionary soldiers (Hawkesworth 2009, 557). These women, often wives and daughters of enlisted men, fulfilled the needs of the military by feeding, clothing, cleaning, and nursing as required. Women civilians supported the war effort in other ways. The homespun movement encouraged them to use locally grown materials to make cloth for themselves and for revolutionary troops. This domestic work was a political statement of patriotism and ensured the success of the resistance against the Townshend Acts via boycott of British goods. Women raised vast sums for the Continental Army and contributed to morale by writing poetry and prose praising the aims of the revolutionaries. During World War I (1914-18), women’s support of militaries was formalized, and they served as auxiliaries in an official capacity, providing medical care to wounded soldiers among other responsibilities. Women became visible workers “at home” on all sides of the conflict. They filled roles vacated by men and took up work for the war effort in munitions factories in droves. In the United States, African American women were able to shift from domestic employment to work in offices and factories for the first time. During World War II (1939-45), women played an even larger role, reprising paid employment, supporting government rationing schemes, and working with the underground resistance in enemy-occupied territories in China, France, and Poland.

Black “Rosie the Riveters”

by Sophie Brodish

When reflecting on World War II, much of the acknowledgment goes to individuals who served in the US armed forces. Around 1 million Black men and women served in the military during the war, representing the largest minority participation in the war effort. Yet today, the contributions of nearly half a million Black civilian counterparts are sidelined, despite their crucial role in the war efforts.

These Black civilians who filled domestic war-related roles within factories, shipyards, and along railroads were known as “Black Rosies.” The term stems from the iconic Rosie the Riveter image, a white female worker dressed in blue coveralls and a red bandanna with the phrase “We Can Do It” underneath her bicep. The image still stands as a symbol for the millions of female laborers working on the US home front, but it erases the true diversity of the work force of the time.

The chance to assist in the war effort provided potential for economic empowerment for Black women, whose opportunities were often restricted to sharecropping and other domestic work, often with little prospect of progress. But the arrival of Black men and women to the war industries was not without pushback by their white counterparts. In 1941 the Fair Employment Practice Committee was created by President Roosevelt, banning discrimination when hiring for government contracts. Despite the order, the conditions for Black women and men remained abysmal, with much of their daily work involving verbal insult or actual injury. No provisions were made for the roughly 700,000 Black families that relocated to cities to fulfill these jobs.

With the conclusion of the war in 1945, the advances made in Black men and women’s employment halted. Many of the plants across the country shut down, and the Black female welders, machinists, mechanics, and riveters were left without work. Nevertheless, the experiences of these “Black Rosies” laid the groundwork for civil rights activism in the following years.

Women civilians also participate in war by using gendered language and coding to encourage men to fight. British government propaganda in World War I appealed to British women to ensure their men enlisted. Women presented white feathers to symbolize cowardice to men not in uniform, a form of public humiliation that drew upon masculine ideologies for effectiveness. Since 1978, women in Afghanistan have played a pivotal role in encouraging their brothers, husbands, and sons to fight, first against the Soviet invaders and then against the Afghan government. A former mujahideen commander reported that mothers not only encouraged their sons to join the jihad, but also actively financed their expenses (Ahmadi and Lakhani 2016, 5). In her now-viral video, Asmaa Mahfouz sparked the protests that led to the January 2011 uprising in Egypt by calling on men and referencing their masculinity:

If you think yourself a man, come with me on 25 January. Whoever says women shouldn’t go to protests because they will get beaten, let him have some honor and manhood and come with me on 25 January.

Women’s influence over men in wartime does not always take the form of encouragement. Cynthia Enloe interviewed a group of nongovernmental organization (NGO) staffers in 2015 and asked if they would receive family support if they enlisted in the military. She reports men from Mozambique and Malawi responding almost in unison, “my mother would never allow my brother to become a soldier” and “my mother does not think becoming a soldier is a respectable career choice for a young man” (Enloe 2015, 8).

While women predominantly participate in war as civilians, they also serve in most twenty-first-century militaries. Militaries have historically been predominantly male organizations. They provide an arena for men to gain access to leadership both within and outside of the institution, thereby perpetuating patriarchal systems. The eponymous hero in Hamilton: An American Musical illustrates this phenomenon. Hamilton’s desire to lead a battalion is intrinsically tied up with his desire to “fly above [his] station after the war,” an aspiration he later achieves (Miranda et al. 2015). Currently, women’s level of inclusion in militaries varies but is generally far lower than that of men. They account for 30 percent of the Eritrean military; 15 percent of the US military, though with a larger proportion of women of color; 6 percent of the Japanese military; and 4 percent of the Polish military. While both men and women have mandatory service in the Israeli Defence Force, only 4 percent of women serve in combat positions, a trend echoed throughout the world. Feminist scholars cite the inherent patriarchal nature of militarization and war as the main explanatory factor here. Boys are socialized in a way that girls are not, and their experience of combative games, competitive sport, and homosocial relationships molds them as potential soldiers from early childhood. The trope of men as warriors and protectors and women as those in need of protection is powerful. In this respect, Cynthia Cockburn argues, “war can seem the fulfilment of gendered destinies” (Cockburn 2013, 439).

The perception of women as in need of protection has been used to mobilize the military and garner public support for war. The post-9/11 “war on terror” (2001 to present) drew heavily on this narrative. First Lady Laura Bush gave the weekly radio address, normally delivered by President Bush, on November 17, 2001, to outline the “horror” of the Taliban Regime. Her core message, that the “fight against terrorism [was] also a fight for the rights and dignity of women,” justified war on moral, gendered grounds (Yaqoob 2008, 150). The Report on the Taliban’s War against Women was released by the US Department of State on the same day. Like Bush’s speech, the report is emotive and uses protectionist language and imagery to justify American intervention in Afghanistan:

The day was much like any other. For the young Afghan mother, the only difference was that her child was feverish and had been for some time and needed to see a doctor. But simple tasks in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan today are not that easy.

The mother was alone and the doctor was across town. She had no male relative to escort her. To ask another man to do so would be to risk severe punishment. To go on her own meant that she would risk flogging.

Because she loved her child, she had no choice. Donning the tent-like burqa as Taliban law required, she set out, cradling her child in her arms. She shouldn’t have.

As they approached the market, she was spotted by a teenage Taliban guard who tried to stop her. Intent on saving her child, the mother ignored him, hoping that he would ignore her. He didn’t. Instead he raised his weapon and shot her repeatedly. Both mother and child fell to the ground. They survived because bystanders in the market intervened to save them. The young Taliban guard was unrepentant—fully supported by the regime. The woman should not have been out alone.

This mother was just another casualty in the Taliban war on Afghanistan’s women, a war that began 5 years ago when the Taliban seized control of Kabul.

The Triumph of For Sama

by Ramona Flores

In Waad al-Kateab’s 2019 documentary For Sama, the director recounts and films her life for five years during the Syrian uprising, framed as a letter to her daughter. The film focuses on not only the immediate danger that al-Kateab faces, but also the radical hope that she has for Sama’s future beyond the conflict.

Brutal in its honesty, the film shows children torn from their loved ones, bloody and scared, as al-Kateab documents the volunteer hospital’s desperate attempts to help the people of Aleppo. In a poetic maneuver through the gore and violence of war, al-Kateab captures the gravity of motherhood, love, and partnership in the nest of turmoil. By framing the documentary as a letter that recounts the early years of her daughter’s life, al-Kateab captures both the suffering and the hope of people living on the ground in a battlefield, a story that is rarely told from the perspective of a woman, let alone a new mother.

Throughout the film, al-Kateab reveals what has to be done when your own government is the enemy, from education and emergency medical services to body recovery and burial. There is no revolution handbook, and this revolution was in the hands, hearts, and minds of the young people who stayed in East Aleppo to help the innocent civilians caught in the mousetrap of war.

In chronicling her life, al-Kateab creates a beautiful tapestry of the human experience. Life, death, her own marriage in a single room, the birth of her daughter in their makeshift hospital, the unbearable weight of loss. Through it all, al-Kateab emphasizes hope. Her own words sum it up perfectly, “the sound of our songs was louder than the bombs falling outside.”

Janine Rich explored Eastern discourses surrounding Muslim women in the context of the war on terror and concluded that the fascination with the burqa, or veil, showed a “racist yet highly sexualised fascination with the ‘exotic Orient’” (Rich 2014). Women from the Middle East have historically been constructed as passive victims without agency, and this simplistic rhetoric was used to legitimize the war on terror. Here, Rich argues, the western feminist belief that Muslim women are oppressed was used as justification for violence.

In recent years, militaries have turned their attention to gender mainstreaming. Gender mainstreaming is not simply an attempt to increase the number of women enlistees, but to effectively include consideration of gender on policies and procedures at all levels. It is fair to say that the former aim is easier and has been more successfully achieved than the latter, and women’s participation has increased over the past decades. Bans on women in combat roles are gradually being lifted: Germany and New Zealand lifted theirs in 2001, Australia and the United States in 2013, and the United Kingdom in 2016. The increase in women’s participation in militaries is not a solely western phenomenon. In 2016, around 35 percent of the Kurdish forces engaged in the fight against ISIS were women (Fitriani and Matthews 2016, 17). They were especially feared by the enemy, as legend says that if a fighter is killed by a woman, the route to heaven is barred. While women in developing countries are increasingly able to engage in armed combat, their experiences are markedly different to their western counterparts, and they do not have access to the same leadership and career opportunities (Prescott 2016, 201). The participation of western women is not without issue, either. The expanded inclusion of women seen in militaries worldwide has not been driven by a desire to promote gender equality, but rather because the execution of operational necessities in modern warfare, especially as seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, are more effective when women are included (Egnell 2016, 74).

The British Army (n.d.) recruitment website for women emphasizes equal pay and promotion by merit, yet in 2018 women made up 11 percent of the workforce but 23 percent of formal complaints, almost half of which focused on bullying, harassment, and discrimination (BBC News 2019). A 2014 survey of all active-duty women in the US Army found that more than a quarter had experienced sexual harassment or gender discrimination during the previous year (Szayna et al. 2015, 38). Women on the front line make men uneasy precisely because militaries are designed around the patriarchal rhetoric that stresses the need for the protection of women. This belief is unfounded within the context of armed combat: a psychological research study following women deployed to Iraq in 2004 found that they were more resilient and less likely to develop posttraumatic stress disorder than their male counterparts (Munsey 2008, 32). Some militaries have attempted to address issues of gender discrimination within the ranks. A study looking at mixed rooms in the Norwegian Army, a feature of the Scandinavian military system for twenty-five years, found that more exposure and interaction between men and women fosters increased mutual understanding and decreased sexualization (Ellingsen, Lilleaas, and Kimmel 2016, 151-64). Thus far, this policy has not been replicated on a larger scale.

Countries That Allow Women in Combat

by Janet Lockhart

Women and girls in all countries have been affected, and even died, during conflicts, as civilians, as guerillas, or as military noncombatants. Many countries have included women in their military forces for centuries, commonly as nurses, administrative personnel, doctors, engineers, cooks, equipment transporters, and other roles.

Today, some countries still do not allow women in the military. Others allow women to enlist in the armed forces, but not in combat positions. Some permit women in combat roles, but with restrictions. A growing number of countries allow women to fulfill any role including combat roles, in their militaries: infantry (foot soldiers), fighter pilots, operators of artillery or other weapons systems, search and rescue teams, special operations, and armored units such as tanks and other equipment.

At present, countries that allow women in combat roles of some kind include Argentina, Australia, Bolivia, Botswana, Canada, China, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Eritrea, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Lithuania, the Netherlands, New Zealand, North Korea, Norway, the Philippines, Poland, Romania, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In general, however, the percentage of women in these roles is low.

Of course, even if they can serve in all military roles, gender equality and fair treatment for women in the armed forces are not guaranteed. And even when female soldiers are accepted and appreciated, they can still be subject to scrutiny of their beauty.

In many countries, arguments against women in combat are fierce and ongoing. Reasons to exclude women include their physical or mental fitness for combat, the fact that they may become pregnant or already have children (forgetting that men are also parents?), and the “cohesion” of units that include women. Importantly, countries that have research supporting the benefits of including women in combat roles include Denmark, Romania, Sweden, and even the United States.

Australia’s first woman prime minister, Julia Gillard, said, “I have a view that men and women are equal. A few years ago I heard [defense chief general] Peter Cosgrove say that men and women should have an equal right to fight and die for their country. I think he is right about that.”

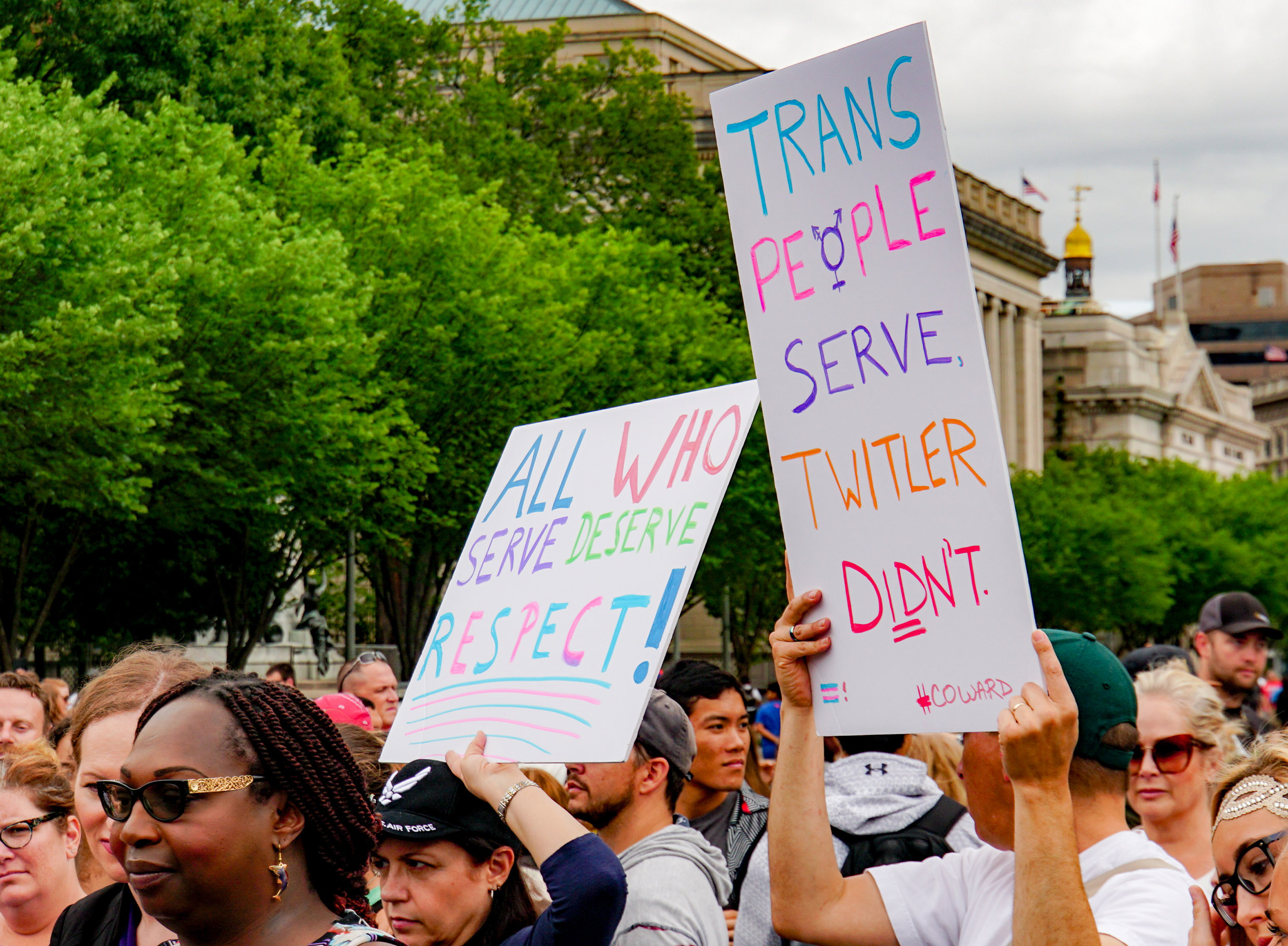

Women who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) are doubly impacted by the need for mainstreaming. Most western, industrialized nations allow openly gay service members, though for many nations this is a relatively new policy. International law has played an important part: a ruling of the European Court of Human Rights in 1999, for example, led the UK military to revise their ban on LGBTQI+ inclusion. In the United States, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was a policy in place from 1994 to 2011. This meant that gay and lesbian service members could not be asked to disclose their sexual orientation but could be discharged if they revealed it. The policy was repealed in 2011. While service members no longer have to hide their sexual orientation, prejudice persists: the code of conduct for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forbids discrimination, but they do not have the means to ensure compliance (Polchar et al. 2014, 69). In addition, only twenty countries allow transgender personnel to serve openly in their militaries. The United States allowed transgender individuals to serve openly between 2016 to 2019, albeit in limited circumstances. The reversal of this policy was announced in 2017 by President Trump via a series of tweets, reading in their entirety:

After consultation with my Generals and military experts, please be advised that the United States Government will not accept or allow Transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military. Our military must be focused on decisive and overwhelming victory and cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption that transgender in the military would entail. Thank you. (@realDonaldTrump, July 26, 2017)

A number of British military commanders, along with the UK Ministry of Defence, responded to state their pride in British transgender personnel and to emphasize their important contributions (BBC News 2017). Despite both international and internal censure, Department of Defence Instruction 1300.28 came into force on April 2, 2019. President Biden reversed the ban via executive order on January 25, 2021, stating his belief that “gender identity should not be a bar to military service, and that America’s strength is found it its diversity” (White House 2021).

The Homomonument: Remembering the Experiences of LGBTQI+ People

by Janet Lockhart

It may not be common knowledge that homosexual people were persecuted during the Holocaust along with other groups, but many lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) people were imprisoned, tortured, and murdered during the Nazi regime. Starting shortly after the end of World War II, COC Nederland, the longest-operating gay rights organization, began to advocate for a monument recognizing the experiences of LGBTQI+ people.

Finally, in 1979, the Homomonument was commissioned. Designed by Karin Daan, a resident of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, it was unveiled to the public in 1987. The Homomonument incorporates three pink triangles—the symbol gay men were forced to wear in Nazi concentration camps, now repurposed as a symbol of LGBTQI+ pride—pointing toward other important sites in Amsterdam, such as the home of Anne Frank. On May 4, the Netherlands’ Annual Remembrance Day, people lay wreaths to commemorate the victims of persecution.

The Homomonument’s meaning now extends to include all people who were or are persecuted, oppressed, or silenced because of their sexual identities. Monuments with similar meanings have been placed in several cities, including Berlin and San Francisco. History must not repeat itself.

Historically, feminist scholars have fallen into two camps when it comes to views on women in the military. “Right to fight” feminists argue that women should be allowed to serve and that blocking their participation in combat perpetuates the view of women as inferior. Others argue that the military is masculinist and violent, and that encouraging women to participate legitimizes a patriarchal institution. This reflects a wider feminist issue: Is it better to challenge the patriarchy from within male-dominated institutions and systems, or remake them from scratch? Claire Duncanson and Rachel Woodward add an interesting dimension to this argument (Duncanson and Woodward 2016, 3-21). Gender mainstreaming, they argue, combines both approaches, drawing on “sameness” to show why women should be allowed to join the military but also “difference” by demonstrating a new way of soldiering: collaborative, communicative and constructive.

Gendered Effects of War

Women who avoid active participation in conflict cannot avoid its effects. The traditional, ungendered assumption that war affects all people equally does not take into account the realities of twenty-first-century warfare. Research suggests that 90 to 95 percent of casualties in the First World War were soldiers (Kvarving and Grimes 2016, 9). Modern methods of warfare have reversed this trend, and now civilians, predominantly women, account for the vast majority of fatalities. Their experiences during war are heavily gendered. Unequal power relationships mean women suffer more when it comes to economic deprivation, the disruption of education, and sexual violence. This is especially the case for those who are simultaneously members of other minority groups. Women are also more likely to be negatively affected by postconflict situations: they, along with the children they are responsible for, comprise 80 percent of refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide.

War exacerbates existing inequalities within society, and societies that are less equal are more likely to go to war. This interplay has a material impact on women. Åsa Ekvall compared data on gender equality, taken from the World Values Survey and the Global Gender Gap Index, with data on conflict taken from the Uppsala Conflict Database and the Global Peace Index (Kvarving and Grimes 2016, 13). She found strong correlations between lack of political and socioeconomic gender equality and armed conflict. Women in war-torn societies are more likely to live in poverty to begin with. The negative financial consequences of war therefore have a larger impact. In agricultural societies, displacement severs women from their home and means of production simultaneously. Women who remained at home before war suffer when the “traditional” male breadwinner is absent. Those who attempt to find work in these circumstances must grapple with scarce employment opportunities, incompatibility with familial responsibilities, and exposure to the risk of physical danger outside of the home. Economic deprivation can have horrifying consequences: in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Cambodia, women have been forced to sell one of their children to ensure the others’ survival (Brittain 2002, 3). Despite these difficulties, war has also offered women new opportunities in the workforce. An anonymous Syrian woman interviewed as part of a humanitarian research project into women, work, and war explained, “Women [in Syria] now know they can do anything—but they learned this lesson the hardest way possible” (Buecher and Aniyamuzaala 2016, 30).

Girls have fewer educational opportunities globally, and this trend is compounded in wartime. Societal upheaval caused by conflict disrupts schooling for all children. Extremist factions, including the Taliban and ISIS, have banned female education. Interestingly, other factions have encouraged education for girls: a woman FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) commander told a peace process advisor that she joined the guerilla group at age 13 in order to learn to read (Bouvier 2016, 15). But this story is an exception to the general rule. Even when schools are able to remain open, girls are less likely to attend. It may be too dangerous or difficult to travel. Economic deprivation means families do not have the funds to send their daughters to school or need them to leave education in order to take up paid employment and contribute to the family purse. Girls may also choose or be forced into early marriage for economic reasons, also necessitating them to abandon education. During the first four years of the ongoing civil war in Yemen (2015 to present), forced and early marriage tripled, and 25 percent of households are currently headed by women under age 18 (International Rescue Committee 2019). Similar patterns can be seen in Afghanistan, Somalia, and Syria. Lack of access to education obviously affects women on an individual level, but it also has implications for society at large, both during war and afterward. Sustainable population growth is more likely when girls are educated, as they go on to have fewer children. The World Bank maintains that education is “a powerful driver of development and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability” (World Bank 2020).

Sexual violence against women has been used as a systematic tool of warfare for millennia. Estimates of sexual assault in twentieth-century wars around the world are sobering: between 20,000 and 80,000 Chinese women were raped in the six-week Nanjing Massacre in 1937; 200,000 Bangladeshi women during the nine-month Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971; 500,000 Rwandan women, predominantly from the Tutsi ethnic group, over a hundred days of Rwandan Genocide in 1994; 10,000-50,000 Bosniak women in the Bosnian War between 1992 and 1995. These are just a handful of examples. A report published by the Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance in 2007 lists sexual violence associated with conflict in fifty-one countries in the preceding twenty years (Cockburn 2013, 440). Feminist scholars have highlighted the ways in which mass sexual assault has been designed to “send a message” to the men of the opposing force, reducing women to possessions to be defiled (Enloe 1984, 5). Sexual assault in warfare can be an example of intersectional oppression. During the Genocide of Yazidi people, perpetrated by ISIS from 2014 to 2017, thousands of women were sold into sexual slavery, a form of strategic ethnic cleansing. The rescue of Yazidi women continues in 2021. LGBTQI+ women have been subject to targeted homophobic and transphobic rape during conflict, notably in the ongoing Colombian (1964 to present) and Syrian (2011 to present) civil wars. Women with disabilities are more likely to suffer human rights violations during and after war, compounded by the fact women are at higher risk of becoming disabled during armed conflict (Ortoleva 2017, 12).

The use of sexual assault as a military tactic can be linked to the strength of patriarchal ideologies in peacetime society. If male family members are expected to protect women from sexual assault, their absence during wartime is palpable. The failure of the state to prevent discrimination of and violence against women sends a message that women’s lives matter less, and systematic sexual violence can be attributed to this viewpoint (Jefferson 2004, 2). Even the Geneva Convention, the core of international humanitarian law, is patriarchal in scope. The treaty for the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War states that women “shall be especially protected against any attack on their honor, in particular against rape, enforced prostitution, or any form of indecent assault.” Coercion against women is here viewed through a protectionist lens. While the Geneva Convention outlawed rape in 1949, sexual assault as a war crime, rather than as a side effect of war, has only been fully acknowledged as such in the past twenty years. Victoria Brittain argues the reason is that during the Bosnian war the women raped were white and European, and therefore attracted mass media attention and censure in the West (Brittain 2002, 6). The United Nations (UN) Security Council adopted Resolution 1820, condemning the use of sexual violence as a tool of war, only in 2008, far later than one might expect.

Sexual violence against women does not stop the moment the war is over. Women are in danger of assault as refugees and internally displaced persons. Organizations whose job it is to help sometimes contribute to this problem. The presence of UN soldiers in refugee camps, for example, increases the presence of prostitutes, often under age 18. These women and girls lack agency, and this transactional sex is in fact another form of sexual assault. Refugees are unlikely to have access to contraception, meaning that for some women there is an increased risk of pregnancy and the stress it entails. The experience of assault has a long-lasting impact. Studies have shown that up to 29 percent of survivors of sexual violence in eastern DRC were stigmatized and rejected by their families and communities (Albutt et al. 2017, 211-27). Women living in societies that are being rebuilt after conflict are also not immune to sexual violence. Jocelyn Kelly et al. plotted incidences of conflict-related fatalities during Liberia’s civil war (1999-2003) against incidences of intimate partner violence (IPV) disclosed in the 2007 Demographic and Health Survey to demonstrate that women who lived in a district that experienced four to five cumulative years of conflict were almost 90 percent more likely to experience IPV than those living in a district with no history of conflict (Kelly et al. 2018, 1-11). Rebecca Horn et al. (2014) interviewed women in postwar Liberia and Sierra Leone to determine their perceptions on the link between conflict and IPV. Women cited the existing patriarchal structures of their communities, including financial dependence and traditional gender relations, as well as the normalization of male violence as a response to frustration during war. More positively, some interviewees believed that opportunities for women to become economically active postconflict simultaneously decreased IPV, both by reducing pressure and associated frustration on male breadwinners and by offering women the means to escape violent relationships.

Women’s experiences during conflict and afterward can differ depending on their age and life stage. An example of this phenomenon in action can be seen in the Sahrawi Refugee camps. The camps are composed of those who fled the Western Sahara War (1975-91) and their descendants, and the camps have been internationally commended as ideal spaces for women. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees claimed in 2004 that “Saharan society is primarily matriarchal and women are totally empowered” (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh 2018, 91-108). Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh investigated these claims, interviewing more than a hundred refugees and fifty aid providers and Sahrawi solidarity activists. She found that while women play a key role in all aspects of life in the camps, their sphere of influence is dependent on age, tribal background, education, and marital status. Women may be (hyper)visible throughout the camps and have access to a wide variety of services and facilities, but there are few spaces for girls outside of their tents despite corresponding public areas for boys and young men. Unmarried women and girls, especially elder daughters, are instead expected to help their mothers with household tasks and care of younger siblings.

We must avoid simplistically dividing women into active participants in war and victims of war. Unequal power relationships affect all women, and it is possible to be simultaneously both a victim and an aggressor. Chris Coulter explores this in the context of the Sierra Leone civil war (1991-2002) (Coulter 2008, 54-73). During the war, 10 to 30 percent of all fighters were women and girls. These fighters were viewed by the rest of the population as monstrous and cold-blooded, even though the vast majority were abducted by rebels and subject to sexual assault if they hesitated when ordered to kill. The trope of women as peaceful does not exist in rural Sierra Leonean traditional culture, and so women fighters were shocking precisely because they demonstrated their true wild and dangerous nature, not because they transgressed gender norms. Coulter argues that the brutality of these fighters toward civilians can be interpreted as a form of redirected revenge perpetuating the cycle of violence, and that while they were not solely victims, they too had little in the way of agency.

War as a Mechanism of Social Transformation

War has long been conceptualized as a pivotal moment in the lives of women, eventually improving their lives. Joan W. Scott outlined variations of the “watershed theme” applied to World War I and World War II (Scott 1984, 2-6). Historians and feminist theorists have argued that during wartime women demonstrated their abilities and received jobs in return, women’s “good behavior” was rewarded with the right to vote, and women’s natural antipathy to war gave them the opportunity to assert themselves in peacemaking organizations. These, Scott argues, are simplistic approaches to a complex topic. It is true that women achieve access to traditionally male spaces during conflict. Women’s employment in Britain increased by 50 percent during World War I. Up to 6 million women in the United States joined the workforce between 1942 and 1945. Women contributed to the war effort, working in the new munitions factories and filling a wide variety of jobs left open by men who joined the military. Waterloo Bridge in London, finished at the end of World War II, is colloquially known as the “Ladies’ Bridge,” as many of the construction workers who built it were women. Whether the gains women make in wartime continue after the conflict is over is another question. Extremist, highly patriarchal factions often fill the gaps left after war. Even in democratic societies, men who cannot work have their gender identity threatened and want to renegotiate. After World War II the number of British women working quickly returned to prewar levels. In the United States the average age of women at marriage and the average age at which they had their first child dropped significantly. This trend also occurred throughout Europe and Asia, and “baby boomers” are still the largest generational cohort in many countries. Media from the 1950s reflects the role of women as wives and mothers, and women in the workplace are nearly invisible. Resurgent patriarchy in action can also be found after more contemporary conflicts. Reconstruction itself can be heavily gendered. In postwar Iraq, humanitarian aid was distributed by mosques, and according to Zainab Salbioff, this meant that women were required to dress in specific ways to gain access to food (Salbioff, Moody, and Mantilla 2003, 9). In the former Yugoslavia, women were urged to leave the workforce and return home to boost the population by having more children (Cockburn 2013, 437-38). Algerian freedom fighters and Colombian guerillas were heartbroken to be effectively told to “get back in the kitchen” (Brittain 2002, 7).

Despite customary attempts to reinstate unequal power relationships with women, there are some examples of women retaining gains made during conflict. Victoria Brittain suggests women who spend wartime in exile are more likely to hold on to power after the war: after the twenty-four-year exile of East Timorese independence activists during the Indonesian occupation of East Timor (1975-99) and the thirty-year exile of the African National Congress during South African apartheid (1960-90), women returned to 30 percent of political seats in both cases (Brittain 2002, 7). Similarly, women in the Kurdish diaspora have been able to actively participate in reconstruction efforts in their new homes (Mojab and Gorman 2007, 58-85). Universal suffrage followed World War I in much of Europe, though we must not make the mistake of ignoring decades of work by women’s suffrage movements before and after the conflict. Women have also been involved in peacemaking and rebuilding nations after war.

Women and Peacemaking

War and militarization are inherently patriarchal and perpetuate gender inequality. Women have aimed to rectify this as peace activists during and after conflict. This does not mean, however, that women are inherently peaceful or that peace is intrinsically feminine. Brounéus (2014, 125-51) demonstrates this in her exploration of the women and peace hypothesis in the context of postconflict Rwanda. She analyzed data from a survey of 1,200 Rwandans conducted in 2006, twelve years after the 1994 genocide in which 800,000 people were murdered. Her findings showed women were significantly more negative than men in their attitudes toward trust, coexistence, and the gacaca, community justice courts. The women surveyed reported experience of more traumatic events than men, as well as higher levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). She concluded that as more women are left to survive the atrocities of war, they may carry a heavier burden of war trauma and that the women and peace hypothesis does not hold in the wake of war. Ascribing peacefulness as a feminine characteristic is in itself patriarchal and can lead to dangerous assumptions about women’s ability to participate in the public sphere. Nevertheless, the inclusion of women in peacemaking and reconstruction efforts is important, especially as research suggests sustainable peace is more likely when women are involved (Principe 2017, 1).

Women Peace Activists

Women in Western Europe mobilized existing feminist groups during World War I, as they believed full participation of women was necessary to achieve lasting peace. In February 1915, a small conference of Women’s Suffrage Associations from Belgium, Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands agreed to arrange and finance an International Congress of Women. The congress took place in April 1915 in The Hague. Traveling across war-torn Europe was no mean feat, and the women also had to cope with the censure of the press. British newspapers referred to the attendees as “blundering,” “babblers,” and “Pro-Hun Peacettes” (Kay, n.d., 2). Even so, 1,136 women attended, representing twelve countries impacted by World War I. The Congress endorsed two principles: that “international disputes should be solved by pacific means” and that “the parliamentary franchise should be extended to women” (Addams, Balch, and Hamilton 1915). They passed twenty resolutions in furtherance of these aims, including proposing the establishment of a Society of Nations and International Court of Justice. Two years later, an all-female peace delegation presented their resolutions to President Woodrow Wilson. His fourteen-point plan echoed many of their proposals. The congress became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), still active today. In 2020 they are focusing attention on structural racism, joining Black Lives Matter activists to advocate defunding and demilitarizing police forces in the United States. The League of Nations, suggested by the congress, was formed in January 1920, and this organization was later succeeded by the UN.

Women have continued their work as peace activists in the contemporary era. The Women in Black protest group, founded by Israeli women in 1988, describes itself as a “world-wide network of women committed to peace with justice and actively opposed to injustice, war, militarism and other forms of violence.” The group is explicitly feminist and believes that male violence against women and war are inherently interlinked. The movement has spawned vigils and nonviolent direct action as a form of war protest in many countries and in many different guises. Women in Black have protested the systematic inequalities of racial capitalism in postapartheid South Africa, personal and public violence against women in Bangalore, and the Serbian regime’s violence against women in Belgrade, to name but three examples. During wartime it is difficult for women to participate in action toward peace because they are most likely to be oppressed. In some cases, though, women have successfully used their ascribed gender role to achieve their aims. In Kenya, Sisters without Borders formed in 2014. Among other activities, Sisters without Borders focuses on ensuring that husbands, brothers, and sons do not join Al-Shabaab, an extremist militant group. The Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace cleverly mobilized their womanhood to achieve peace. Married women threatened to withhold sex until the conflict was over. In 2003 a group of two hundred women surrounded the peace talks and blocked anyone from leaving. To avoid being arrested, they threatened to strip naked, an act feared by the men involved who believed it would curse them. The peace talks were successful, and Liberia went on to elect one of the leaders their first female head of state (Principe 2017, 7).

Out of 106 Nobel Peace Prize laureates, 17 have been women, a higher percentage than any other Nobel Prize. Two presidents of WILPF, Jane Addams and Emily Greene Balch, won the prize in 1931 and 1946, respectively. Betty Williams and Mairead Maguire, joint winners in 1976, cofounded a mass movement focused on ending the Troubles in Northern Ireland and marched with more than ten thousand Catholic and Protestant women to call for peace. Wangarĩ Muta Maathai won in 2004 for her contribution to “sustainable development, democracy, and peace.” She was both the first African woman and the first environmentalist to win the prize, and in her Nobel lecture she commended the committee for linking the critical issues of environment and democracy. In 2011 the prize was jointly awarded to Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Leymah Gbowee, and Tawakkol Karman “for their non-violent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation in peace-building work,” the former two for their actions during and after the Liberian peace talks. Malala Yousafzai, the youngest Nobel laureate, won in 2014 for her struggle against the suppression of children and young people, and for the right of all children to an education.

Nadia Murad Basee Taha, the most recent woman winner and the first Iraqi and Yazidi to be awarded a Nobel Prize, won in 2018 for her efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war. Nadia was captured by ISIS in August 2014 and held as a slave until she escaped three months later. She has since worked with the UN Security Council to draw their attention to human trafficking and set up Nadia’s Initiative, a nonprofit organization focused on helping victims of sexual violence and to rebuild the Yazidi homeland. While these individual women have been recognized for their efforts to bring about peace, many more go unrecognized or have been unable to participate in the process at all.

Stronger Than Hate

by Sarah Baum

Try to imagine yourself living in a corner of the world that refuses to educate half the population. Now imagine yourself being part of that half and being denied the right to learn simply because you were born the wrong gender. Malala Yousafzai lived that life. Born in 1997 in the Swat Valley of Pakistan, she hungered for knowledge and education from an early age. But when the Taliban took control of her home region, she found herself being denied this basic human right, along with things like attending dances and watching television. It was 2007, and Malala was only 10 years old, but she became an outspoken advocate for the right of women and girls to be educated.

While she was sharing her voice, by the end of 2008, the Taliban destroyed more than four hundred schools. This didn’t stop her. She appeared on television shows and wrote a blog about life under Taliban rule for the BBC, all while continuing to defy their dictates not to go to school. On October 9, 2012, while she was riding a bus home from school, two Taliban men stopped the bus and asked for her by name. They shot at her three times, hitting her in the head and leaving her for dead. Malala was only 15 years old; her crime, in their eyes, was the desire to learn.

Malala didn’t die of her wounds, and miraculously she sustained little lasting physical harm and no brain damage. These men filled with hate who tried to steal her life and her knowledge failed at both attempts. Her assault could have silenced her, but instead it only spurred her to become more outspoken, more of an advocate. She continues to work tirelessly to see that all people, no matter their gender, have the same access to a quality education—all while attending school herself. At 17, just two years after her assault, she became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. In 2020, she graduated from Oxford University. Malala remains a young woman who not even a Taliban bullet could stop from advocating education for all.

Women and UN Security Council Resolution 1325

On October 31, 2001, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (known as UNSCR 1325). The resolution aims to reverse the exclusion of women in the resolution of conflict by acknowledging women as critical actors to achieve peace at all levels, recognizing the importance of the Windhoek Declaration and the Namibia Plan of Action on Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in Multidimensional Peace Support Operations. The declaration and plan of action outline a series of practical measures to achieve gender mainstreaming, including a target of 50 percent women leaders in peace support operations, a gender affairs unit to be a standard component of all missions, and for women to be an integral part of all negotiating teams. UNSCR 1325 has had a positive impact on the participation of women in peacekeeping: between 1957 and 1989, only 20 women served as UN peacekeepers, increasing to 5,284 by January 2020, 6.4 percent of UN military and police personnel (Baldwin and Taylor 2020, 2). In the thirty-one major peace processes conducted worldwide between 1992 and 2011, however, women comprised only 9 percent of negotiators, 4 percent of signatories, 3.7 percent of witnesses, and 2.4 percent of chief negotiators (Kuehnast and Robertson 2016). The UN looks unlikely to meet its own targets, and independent experts have called for more work to ensure the goals of UNSCR 1325 are met (Rehn and Sirleaf 2002).

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325: Twenty Years Later in Israel and Palestine

by Lauren Grant

October 2020 marked the twentieth anniversary of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 on women, peace, and security. Besides recognizing the devastating and disproportional impact of conflict on women and girls, the resolution urges states to increase women’s participation in conflict management and resolution, stressing “the importance of women’s involvement in peace and security issues to achieve long lasting stability.” While the landmark resolution serves as “a beacon in the dual struggle against militarism and patriarchy,” women’s rights activists across the world have questioned its effectiveness twenty years later.

In the Middle East, women were calling for the “greater involvement of women in the quest for an equitable solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conundrum” long before the resolution’s 2001 adoption, advocating for transformation of gender relations, an end to Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, advancement of Palestinian self-determination, and meaningful reconciliation. Despite the perceived win for joint Israeli-Palestinian women’s peace efforts, many claim the resolution has failed to create the transformational outcomes on which women’s lives and freedoms in these territories depend.

Reasons for the failures are manifold: Dissatisfaction arising from Israel’s continued occupation of the Palestinian territories. “Negative political and socioeconomic impacts” on Palestinian women that impede the resolution’s progress and subject them to further violence and marginalization. Patriarchal, sociocultural, and political norms in both Israel and Palestine that hinder women’s participation in peace and security discussions. “Cleavages between women along social, ethnic, religious and economic lines” (Kevorkian 2010) often mean that even where women’s involvement has increased, it has been limited to privileged, middle-class women, without including a diversity of lived experiences and perspectives, contrary to the resolution’s binding obligations. Most hearty attempts to mainstream gender into the sociopolitical landscape have been limited to academic circles and nongovernmental organizations.

While a significant number of peacekeeping initiatives have been led by women in Israel and Palestine, “the voices of women are still silenced or dominated by those of their male counterparts,” and impediments to implementation of UNSCR 1325 over the past two decades have actually allowed gender inequality to grow. Women’s rights activists call for more intersectional ways of enacting the resolution, in which grassroots voices are placed at the center of solutions for peace, and the needs of all women are accurately reflected at the negotiating table.

References

Kevorkian, Nadera Shalhoub. 2010. The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 Implementation in Palestine and Israel 2000-2009. Oslo: Norwegian Church Aid.

Feminist scholars have criticized UNSCR 1325 for perpetuating the very gender norms that contribute to women’s inequality and likelihood to be negatively affected by war (True 2009, 41-50). Women are represented as needing protection from men, and other facets that make them more vulnerable during war are not considered. This protectionist narrative can influence the experience of women peacekeepers, whose mission leaders may not allow them full involvement in peacekeeping missions on the basis of their gender and perceived need for protection (Baldwin and Taylor 2020, 1). Diversity in womanhood is also not considered, and so women are often viewed as a homogenous group rather than as individuals with different needs. There is, however, some evidence of progress over the past decade. In 2014, Miriam Colonel-Ferrier was the first woman to act as chief negotiator and sign a final peace accord with a rebel group, ending the forty-year conflict between the Filipino government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. During the Colombian peace process in 2016, one-third of delegates were women, and a gender subcommission was included in a peace process for the first time. The inclusion of women from diverse racial and economic backgrounds broadened the agenda. The final peace treaty contained provisions seeking gender equality, including plans to address socioeconomic issues and LGBTQI+ discrimination (Cóbar, Bjertén-Günther, and Jung 2018, 14). These two recent examples show how peace processes can be improved if women actively participate.

Conclusion

We must examine war using gender as a category of analysis to understand its true cost. War and militarization perpetuate patriarchal systems, and women suffer more from socioeconomic changes, displacement, and violence during and after conflict. Those who actively participate in war are subject to an inequitable distribution of power despite ongoing attempts to implement gender mainstreaming. While war can sometimes disrupt existing unequal gender structures, these are often re-made. Women have historically been excluded from reconstruction efforts on a mass scale, even though their inclusion makes sustained peace more likely. In recent years, women peace activists have made great strides in this arena, but further work to consolidate these opportunities and improve the lives of women is vital.

Learning Activities

- Milburn argues that it is crucial to use gender as a category of analysis when discussing war and militarization. How does she support her argument?

- In what ways do women participate in war, according to Milburn?

- In what ways has protecting women been used to justify the US war on terror?

- What is gender mainstreaming in the military? How does it affect women and LGBTQI+ members of the military?

- What are the gendered effects of war, according to Milburn?

- Milburn discusses several peace activist groups, such as Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (US), Women in Black (Israel), and Sisters without Borders (Kenya). Working alone, with a partner, or in a small group, choose one of these organizations and conduct online research on it. What are the specific aims of the organization? How do activists work to support those aims? What do you learn about peace activism from your research?

- Add the following key term to your glossary: gender mainstreaming.

References

Addams, Jane, Emily Greene Balch, and Alice Hamilton. 1915. Women at the Hague: The International Congress of Women and Its Results. New York: Macmillan.

Ahmadi, Belquis, and Sadaf Lakhani. 2016. Afghan Women and Violent Extremism: Colluding, Perpetrating, or Preventing? Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR396-Afghan-Women-and-Violent-Extremism.pdf.

Albutt, Katherine, Jocelyn Kelly, Justin Kabanga, and Michael VanRooyen. 2017. “Stigmatisation and Rejection of Survivors of Sexual Violence in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.” Disasters 41, no. 2, 211-27. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/disa.12202.

Baldwin, Gretchen, and Sarah Taylor. “2020. Uniformed Women in Peace Operations: Challenging Assumptions and Transforming Approaches.” International Peace Institute. June 2020. https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2006-Uniformed-Women-in-Peace-Operations.pdf.

BBC News. 2017. “UK Military Chiefs Praise Transgender Troops.” July 26, 2017. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-40733701.

———. 2019. “Complaints by Female and BAME Military Staff a ‘Serious Concern.’” August 7, 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-49259115.

Bouvier, Virginia M. 2016. Gender and the Role of Women in Colombia’s Peace Process. New York: UN Women. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Gender-and-the-Role-of-Women-in-Colombia-s-Peace-Process-English.pdf.

British Army. “Women in the Army.” Accessed October 30, 2020. https://apply.army.mod.uk/what-we-offer/what-we-stand-for/women-in-the-army.

Brittain, Victoria. 2002. “Women in War and Crisis Zones: One Key to Africa’s Wars of Underdevelopment.” Crisis States Research Centre Working Papers 1, no. 21, 1-12. http://www.lse.ac.uk/international-development/Assets/Documents/PDFs/csrc-working-papers-phase-one/wp21-women-in-war-and-crisis-zones.pdf.

Brounéus, Karen. 2014. “The Women and Peace Hypothesis in Peacebuilding Settings: Attitudes of Women in the Wake of the Rwandan Genocide.” Signs 40, no. 1, 125-51. https://doi.org/10.1086/676918.

Buecher, Beatrix, and James Rwampigi Aniyamuzaala. 2016. Women, Work and War: Syrian Women and the Struggle to Survive Five Years of Conflict. Amman: CARE International. https://care.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Syria_women_and_work_report_logos_07032016_web.pdf.

Cóbar, José Alvarado, Emma Bjertén-Günther, and Yeonju Jung. 2018. “Assessing Gender Perspectives in Peace Processes with Application to the Cases of Colombia and Mindanao.” SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security 6, 1-32. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/sipriinsight1806.pdf.

Cockburn, Cynthia. 2013. “War and Security, Women and Gender: An Overview of the Issues.” Gender and Development 21, no. 3, 433-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.846632.

Coulter, Chris. 2008. “Female Fighters in the Sierra Leone War: Challenging the Assumptions?” Feminist Review 88, 54-73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30140875.

Duncanson, Claire, and Rachel Woodward. 2016. “Regendering the Military: Theorizing Women’s Military Participation.” Security Dialogue 47, no. 1, 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010615614137.

Egnell, Robert. 2016. “Gender Perspectives and Military Effectiveness: Implementing UNSCR 1325 and the National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security.” PRISM 6, no. 1, 73-89. https://cco.ndu.edu/PRISM/PRISM-volume-6-no1/Article/685108/gender-perspectives-and-military-effectiveness-implementing-unscr-1325-and-the/.

Ellingsen, Dag, Ulla-Britt Lilleaas, and Michael Kimmel. 2016. “Something Is Working—But Why? Mixed Rooms in the Norwegian Army.” NORDA, Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 24, no. 3, 151-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2016.1236037.

Enloe, Cynthia. 1984. “Women and Militarization: A Seminar.” Radical Teacher, no. 26, 2-7. www.jstor.org/stable/20709439.

———. 2015. “The Recruiter and the Sceptic: A Critical Feminist Approach to Military Studies.” Critical Military Studies 1, no. 1, 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/23337486.2014.961746.

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena. 2018. “Ideal Women, Invisible Girls? The Challenges of/to Feminist Solidarity in the Sahrawi Refugee Camps.” In Feminism and the Politics of Childhood: Friends or Foes?, edited by Rachel Rosen and Katherine Twamley, 91-108. London: University College London Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt21c4t9k.12.

Fitriani, Randolph G. S. Cooper, and Ron Matthews. 2016. “Women in Ground Close Combat.” RUSI Journal 161, no. 1, 14-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2016.1152117.

Hawkesworth, Mary. 2009. “Women, War and Peace.” In Women Worldwide: Transnational Feminist Perspectives on Women, edited by Janet Lee and Susan Shaw, 553-78. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Horn, Rebecca, Eve Puffer, Elisabeth Roesch, and Heidi Lehmann. 2014. “Women’s Perceptions of Effects of War on Intimate Partner Violence and Gender Roles in Two Post-Conflict West African Countries: Consequences and Unexpected Opportunities.” Conflict and Health 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-8-12.

International Rescue Committee. 2019. “Four Ways the War in Yemen Has Impacted Women and Girls.” Last modified December 20, 2019. https://www.rescue.org/article/4-ways-war-yemen-has-impacted-women-and-girls.

Jefferson, LaShawn R. 2004. “In War as in Peace: Sexual Violence and Women’s Status.” In Human Rights Watch World Report. New York: Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/legacy/wr2k4/15.htm.

Kay, Helen. n.d. “The Women Who Tried to Stop World War One.” Accessed October 30, 2020. https://wilpf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Introduction-to-booklet-These-Dangerous-Women.pdf.

Kelly, Jocelyn T. D., Elizabeth Colantuoni, Courtland Robinson, and Michele R. Decker. 2018. “From the Battlefield to the Bedroom: A Multilevel Analysis of the Links between Political Conflict and Intimate Partner Violence in Liberia.” BMJ Global Health 3, 1-11. https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/2/e000668.

Kuehnast, Kathleen, and Danielle Robertson. 2016. “Women Charting a New Course on Peace and Security.” US Institute of Peace. March 1, 2016. https://www.usip.org/publications/2016/03/women-charting-new-course-peace-and-security.

Kvarving, Lena P., and Rachel Grimes. 2016. “Why and How Gender Is Vital to Military Operations.” In Handbook on Teaching Gender in the Military, 9-25. Geneva: Geneva Center for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) and Partnership for Peace Consortium (PfPC), 2016. https://www.dcaf.ch/sites/default/files/imce/Teaching%20Gender%20in%20the%20Military/DCAF-PfPC-Teaching-Gender-Military-Ch1-Why-how-gender-is-vital-to-military.pdf.

Miranda, Lin-Manuel, Leslie Odom Jr., Anthony Ramos, and Christopher Jackson. 2015. “Meet Me Inside.” Track 16 on Hamilton: An American Musical, Original Broadway Cast Recording. Atlantic.

Mojab, Shahrzad, and Rachel Gorman. 2007. “Dispersed Nationalism: War, Diaspora and Kurdish Women’s Organizing.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 3, no. 1, 58-85. www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/mew.2007.3.1.58.

Munsey, Christopher. 2009. “Women and War.” Monitor on Psychology 40, no. 8, 32. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2009/09/women-war.

Ortoleva, Stephanie. 2017. “Accounting for Women and Girls with Disabilities in Conflict and Crisis Situations: Recommendations for Action and Implementation.” Human Rights 42, no. 4, 12-13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26423422.

Polchar, Joshua, Tim Sweijs, Philipp Marten, and Jan Galdiga. 2014. LGBT Military Personnel: A Strategic Vision for Inclusion. The Hague: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep12586.

Prescott, Jody. 2016. “The Law of Armed Conflict and the Operational Relevance of Gender: The Australian Defence Force’s Implementation of the Australian National Action Plan.” In Imagining Law: Essays in Conversation with Judith Gardam, edited by Dale Stephens and Paul Babie, 195-216. South Australia: University of Adelaide Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1sq5x0z.13.

Principe, Marie A. 2017. Women in Non-Violent Movements. Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR399-Women-in-Nonviolent-Movements.pdf.

Rehn, Elisabeth, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. 2002. Women, War and Peace: The Independent Experts’ Assessment on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Women and Women’s Role in Peace-Building. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/3F71081FF391653DC1256C69003170E9-unicef-WomenWarPeace.pdf.

Rich, Janine. 2014. “Saving Muslim Women: Feminism, US Policy and the War on Terror.” International Affairs Review (Fall). https://www.usfca.edu/sites/default/files/arts_and_sciences/international_studies/saving_muslim_women-_feminism_u.s_policy_and_the_war_on_terror_-_university_of_san_francisco_usf.pdf.

Salbioff, Zainab, Maryam Moody, and Karla Mantilla. 2003. “Interview: After the War. Women in Iraq.” Off Our Backs 33, no. 7/8, 11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20837867.

Scott, Joan W. 1984. “Women and War: A Focus for Rewriting History.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 12, no. 2, 2-6. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40004302.

Szayna, Thomas S., Eric V. Larson, Angela O’Mahony, Sean Robson, Agnes Gereben Schaefer, Miriam Matthews, J. Michael Polich, et al. 2015. “The Integration of Women and Other Excluded Groups into the U.S. Military: The Historical Experience.” In Considerations for Integrating Women into Closed Occupations in the U.S. Special Operations Forces, 15-46. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt19rmddv.12.

True, Jacqui. 2009. “The Unfulfilled Mandate: Gender Mainstreaming and UN Peace Operations.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 10, no. 2, 41-50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43133572.

White House. 2021. “Fact Sheet: President Biden Signs Executive Order Enabling All Qualified Americans to Serve Their Country in Uniform.” January 25, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/25/fact-sheet-president-biden-signs-executive-order-enabling-all-qualified-americans-to-serve-their-country-in-uniform/.

World Bank. 2020. “Education.” Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education.

Yaqoob, Salma. 2008. “Muslim Women and War on Terror.” Feminist Review, no. 88, 150-61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30140883.

Image Attributions

12.1 “Women of Britain say – ‘Go!’” by ArchivesOfOntario is available under CC PDM 1.0

12.2 “Women of the IDF” by Israel Defense Forces is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

12.3 “2017.07.29 Stop Transgender Military Ban, Washington, DC USA 7729” by tedeytan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

12.4 “BE001076” by Tommy Japan 79 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

12.5 “Marcha Contra las FARC en Medellín Colombia 4 de febrero 2008” by medea_material is licensed under CC BY 2.0

12.6 “Sierra Leone and Brig. Gen. Kabia: A progressive voice for African military women – ALFS 2010” by US Army Africa is licensed under CC BY 2.0

12.7 “Female workers in action at the Pictou shipyard, Nova Scotia, January 1943 / Travailleuses à l’oeuvre au chantier naval de Pictou, Nouvelle-Écosse, janvier 1943” by BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives is licensed under CC BY 2.0

12.8 “Gacaca courts- ©Elisa Finocchiaro” by elisa finocchiaro is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

12.9 “The San Francisco Conference, 25 April-26 June 1945” by United Nations Photo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

12.10 “The Security Council” by United Nations Photo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

12.11 “UNIFIL Malaysian Women Peacekeepers” by United Nations Photo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0