Sexualities Worldwide

Sharadha Kalyanam

We’re survivors of childhood violence with black eyes

in common from mothers who hated our difference…

Your people as well as mine slaughtered in millions

Queer we’re still open season

My fingermarks on your ass are loving you…

Desire red & raw as wounds we disguise

we’re open season.

—Chrystos, In Her I Am

These lines by Menominee poet and activist Chrystos tell stories of sexual violence and abuse and how colonial heteropatriarchy separated Indigenous women from their sexualities. Chrystos writes that it is possible for Indigenous queer and Two-Spirit people to reclaim and realize their sexuality and sexual freedom by engaging in healing through the erotic, which Cherokee Two-Spirit poet Qwo-Li Driskill has argued Chrystos does through her erotic poetry for Native Two-Spirit women. Chrystos’s work shows how the genders and sexualities of Indigenous and other colonized peoples were regulated through colonialism and how Native peoples are healing themselves by theorizing the Indigenous erotic (Driskill 2004, 58-59).

Sexualities have been and continue to be closely and violently regulated by a number of historical and ongoing structures, including colonialism, globalization, and nationalism. Women’s sexualities, queer sexualities, and other nonnormative sexualities are sites of intense scrutiny, regulation, and control. This chapter addresses sexualities in a global context and the ways in which they are connected with and shaped by race, gender, class, age, and (dis)ability. Sexuality requires an intersectional understanding, which asks that we center the ways that Black, Indigenous, and communities of color have historically had and continue to have their own systems of gender and sexuality prior to colonial contact as well as how colonial conquest took place through the violent control of Indigenous gender and sexual practices. Western colonial forces pathologized the sexualities of colonized peoples in order to justify European conquest and settlement against non-Christian “savages.”

Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera

by Charissa V. Jones

Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were friends and gay and transgender activists from the mid-1960s until their respective deaths. Best known for their participation in the 1969 Stonewall Riots, they were admired within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex plus (LGBTQI+) community for unapologetically dressing and living their truth, even in the face of judgment, harassment, and ridicule. Marsha P. Johnson was a Black transwoman and drag queen known for her vibrant and flamboyant expression of her gender and personality. The “P.” in Marsha’s name stood for “Pay it no mind”—an expression that reflected how she felt about people who asked the intrusive question whether she was a “boy” or a “girl.”

Sylvia Rivera was a Puerto Rican transwoman whose gender identity was complex and shifted throughout her life. Although she did refer to herself as a “half-sister,” gay man / gay girl, drag queen, and later a transwoman, she was not a fan of labels and the power they held.

In 1970, Marsha, Sylvia, and a group of drag queens formed the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). An offshoot of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), in which they were active, STAR provided support for gay people facing homelessness, gay people in prison, and youth who were becoming “street drag queens” to survive. Unfortunately, as some LGBTQI+ movements became normalized, their relationship with the radical politics of Marsha and Sylvia and other early gay activists became strained. Marsha and Sylvia were fighting for liberation—not just for gay and transgender people, but for everyone—as they worked against systemic racism, poverty, and health disparities. Neither has been completely acknowledged or celebrated for their contributions to civil rights within their racial and ethnic communities, either. It is important to understand Johnson’s and Rivera’s legacies, how they put their bodies on the line, and took up space to create places in the world for themselves and for others.

Through the various sections, this chapter outlines the key concepts and themes on sexualities worldwide. It begins with colonial histories of sexuality and the ways that processes and structures like colonialism, imperialism, globalization, and settler-colonialism impacted sexualities and continue to shape and control them. The chapter looks at how dominant western expressions and frameworks may not apply in Third World[1] settings and how they selectively erase local and regional expressions of gender and sexuality. It also examines how sexualities were viewed and regulated based on colonial binaries of white and non-white, normative and nonnormative. We will then explore the cultural variations in sexualities and the flow of dominant sexual cultures from the Global North to the Global South,[2] and discuss disability and sexuality in a global context, followed by the sexual politics of pornography. The section then ends with a discussion on pinkwashing and reflections on ongoing activisms and movements to build radical coalitional futures.

Key Terminologies

Before getting into the various sections below, I discuss working definitions of several key terms used in this chapter. Some of these terminologies are settler-colonialism, heteropatriarchy, heteronormativity, white supremacy, and genocide. Through this chapter, settler-colonialism is defined as the ongoing structure (Wolfe 2006) in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, where European settlers, through the process of stealing Indigenous lands, have claimed the land as their own. Settler-colonialism employs the “logic of elimination” (Wolfe 2016), whereby European settlers “engineer the disappearance of the original inhabitants everywhere except in nostalgia” (Shoemaker 2015). Arvin et al. (2013) write, “Settler-colonialism is a persistent social and political formation in which newcomers/colonizers/settlers come to a place, claim it as their own, and do whatever it takes to disappear the Indigenous peoples that are there” (12). Settler-colonialism utilizes the strategy of genocide, both human and cultural, to destroy humans and their cultures, religions, languages, and memories.

Heterosexuality is the binary western organization of genders and sexualities where the heterosexual relationship between cisgender men and women is considered as the norm, and other forms of sexuality are considered deviant and abnormal. This relates to heteronormativity, which is the belief that heterosexuality is the “normal” or default sexual orientation. Michael Warner first defined heteronormativity by arguing, “Het[erosexual] culture thinks of itself as the elemental form of human association, as the very model of intergender relations, as the indivisible basis of all community, and as the means of reproduction without which society wouldn’t exist” (Warner 1993, xxi). Heteropatriarchy, then, is a system where heterosexuality and patriarchy are considered “normal” and “natural.” The United States is a white supremacist heteropatriarchal society, where racialized and gendered people always already have a relationship with settler-colonialism (Smith 2016). Gender and sexuality are distinct but overlapping identities, and the systems of power that produce and uphold them are intertwined. Z. Nicolazzo (2017) has theorized the term “compulsory heterogenderism” to describe how gender and sexuality are often conflated by cisgender people who sometimes perceive the sexualities of trans folks as a result of their gender presentation. “Sexualities (e.g., being gay, lesbian, bisexual) are distinct vectors of identity from transgender identities,” Nicolazzo (2017, 246) writes, the way cisgender folks (mis)understand gender by viewing it through sexuality-based stereotypes that render trans identities “invisible, unknown, and as a result, unknowable” (Nicolazzo 2017, 253). This understanding shows the ways in which categories of sexualities—like queer, straight—rely upon a rigid gender binary system and heterosexism, wherein only compulsory heterosexual relationships between cisgender men and women are considered “natural” and “normal.”

Countries Where Homosexuality Is Accepted

by Janet Lockhart

Over the centuries, acceptance of homosexuality has varied widely. In Belgium, for example, homosexuality was legal as far back as the 1700s; however, it is illegal in many countries today. A Pew Research Center report shows that between 2013 and 2019, many countries have shown a marked increase in acceptance of homosexuality, but there are still differences.

Geographically, societal attitudes toward homosexuality tend to be more positive in Western Europe and North America (the United States ranks lower than most other countries in these regions, however). Several Latin American countries also indicated high levels of acceptance.

Across nations, the following groups of people tend to look more favorably upon homosexuality: people on the political left; people in wealthier and more developed economies; people who are unaffiliated with a religious group or not religious; women compared to men (in some places); people with higher levels of education; younger adults compared to older adults; and Catholics and some Jews, compared to Protestants, Evangelicals, and Muslims.

Besides laws protecting people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+), such as legal same-sex marriage, another indicator of societal acceptance is the presence of LGBTQI+ Pride events, and specific cities or districts with venues and activities welcoming LGBTQI+ people. Some of these include Amsterdam, Auckland, Barcelona, Berlin, Bogota, Brussels, Buenos Aires, Copenhagen, Lisbon, London, Melbourne, Montreal, Ottawa, Paris, Reykjavik, Stockholm, Sydney, Toronto, and Vancouver.

Colonialism, Imperialism, and Chattel Slavery

Settler Colonialism and Colonial Binaries

Colonialism, imperialism, and globalization have and continue to police and control sexualities and sexual freedom around the world. Colonialism has and continues to manifest in several ways depending on the intentions and motivations of colonizing powers. In the context of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, settler-colonialism continues to be present and operate as a structure that actively erases Indigenous presence by rendering Indigenous people into the past. Settler-colonial projects center and enforce Euro-Christian heteronormativity onto Indigenous people’s bodies and communities. Picq (2020) writes, “Sexuality was a terrain to frame the Native as pervert and validate European violence against the non-Christian other, labeled as savage, heretic, and sodomite.” Picq argues that colonizing processes were based on the “Western practice of temporalizing difference” (2020, 10), which means that European powers engaged in viewing and locating non-white, non-western “others” outside of Christian faith in a static, primitive past in need of modernizing and civilizing. This practice of othering continues in the way western lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) rights discourses and the connection between western liberal democracy in the developed world and “sexual modernity” continue to be centered in global discourses on gender and sexuality, locating non-western sexual expressions in a marginal, primitive, static past (Picq 2020). For example, let us look at same-sex marriage. Spade has argued that in the United States there is extensive focus on a conservative, equal rights-based model that is perpetuated through “the myth of equal opportunity” (2015, 30). He suggests that rather than focusing on activisms on radical restructuring of dominant institutions, which include the prison industrial complex, the nonprofit industrial complex, and the military industrial complex, there is an increasingly assimilative quest for inclusion and recognition by these institutions. The benefits of same-sex marriage are only available to privileged gay and lesbian people who can in turn access other benefits like child welfare, for example. Marriage, however, or “the government’s privileged relationship status” (Spade 2015, 31), does not guarantee protection under family law and child welfare because reducing queer and trans recognition to marriage rights alone does not contend with how race, class, (dis)ability, immigration status, and other factors determine the distribution of these benefits as well as life chances (Spade 2015).

Colonization, Gender, and Two-Spirit People in Indigenous Communities

by Lily Sendroff

Two-Spirit is a modern umbrella term used by some Indigenous North Americans to refer to people and ceremonial roles outside of the gender binary. In Native American cultures, Two-Spirit people are not considered to be strictly male or female—instead, they occupy a distinct gender status beyond sex. Across North American tribes, there are certain similarities between Two-Spirit people. One of the most important similarities is specialized work roles—Two-Spirit men often take on traditionally feminized forms of labor and combine them with important ceremonial male roles. Two-Spirit women, in contrast, take on what is traditionally masculine work. Beyond labor, Two-Spirit people are distinguished by a variety of other traits, such as demeanor, dress, and social roles.

There are important variations in Two-Spirit identity between tribes—in some, Two-Spirit males and females are referred to by the same term, amounting to a “third gender.” In others, there are distinctions between Two-Spirit males and females, creating a fourth gender. For example, Navajo culture recognizes five genders: asdzaan (woman), hastiin (man), and nadleeh (the Navajo iteration of Two-Spirit), which is then subcategorized into female-bodied nadleeh (masculine female) and male-bodied nadleeh (feminine male).

Conceptualizations and articulations of gender vary between Indigenous communities—not all Indigenous tribes and people perceive Two-Spirit in the same way, and not all Indigenous people even recognize the term “Two-Spirit.” For those who do embrace the term, Two-Spirit identity directly connects to ancestral practices that were intentionally targeted by colonization. Through religion, family separation via boarding schools, and state-sanctioned violence by government agencies, colonizers sought to eliminate Indigenous practices and people by forcefully imposing western ideals. Two-Spirit people and cultural roles were especially targeted owing to rigid western conceptualizations of gender and sexuality. Many Two-Spirit people went underground or disappeared altogether from certain tribes, erasing integral components of native cultures and histories.

Today, an increasing number of queer-identifying Indigenous people in North America use the term Two-Spirit. There have been Two-Spirit conferences since the 1990s, providing a space for community and opportunity to continue the ongoing process of Two-Spirit revival and resistance against Indigenous erasure.

The genders and sexualities of colonized peoples were outside of European, binary norms, and understandings and were framed as deviant or perverse. For example, under British colonial rule in the South Asian subcontinent, hijras[3] were classified as “eunuchs,” and under the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA), the colonial government vowed to slowly implement a “cultural elimination” of hijras by surveilling them and policing their public presence and then exterminating all of them (Hinchy 2019, 2). During this time, the colonial government saw them as a threat not only to morality but also as individuals that undermined British colonial authority. British administrators had “official concern” with the hijras and implemented policies that exercised control over gender expression, sexual behavior, as well as their kinship and intimate relationships (Hinchy 2019, 24). Managing the gender, sexuality, and domesticity of the hijras was one of the many ways in which the British colonial government implemented its idea of the ideal state. Hijras were a source of “heightened colonial panic” (Hinchy 2019, 24), deemed immoral or unfit to be moralized and governed, thereby inciting the British to attempt to eradicate them entirely. The colonial regulation of hijra bodies and laws that rendered them as criminals provide an important context and inform the stigmatization, marginalization, and continued criminalization that hijra communities experience today.

In North America, joyas (Spanish for “third-gender people”) lived among the California Indian tribes (Miranda 2010). Joyas were targeted and killed through the Spaniards’ genocidal policies in what Esselen and Chumash writer and poet Miranda calls the “gendercide.” The Spaniards saw joyas and perceived them through their “third gender,” and the fact that they dressed and behaved like women and had sexual relations with men was incomprehensible to the Spaniards. In different colonial moments, for example, in British and Spanish imperialisms, gender and sexuality were not considered as separate categories, and there was no conception of sexualities. Colonized peoples were sorted based on their gender and racial embodiments as heteropatriarchy was violently imposed on them. Writing about Cherokee Two-Spirit communities, Driskill (2016) argues that the term “Two-Spirit” in itself is a critique of the terminologies and labels used in dominant white LGBTQI+ communities. The word “queer” refers to identities, sexualities, and sexualized practices, whereas Two-Spirit is about “gendered experiences and identities that fall outside of dominant European gender constructions” (Driskill 2016, 30). In order to understand how colonial projects and technologies continue to control sexualities and genders, it is critical to understand the constructions of genders and sexualities on colonized lands; “gender” and “sexuality” are colonial constructions and ideas that are projected to make sense of precolonial pasts (42).

Mytheli Sreenivas writes that even before Europeans invaded territories in Africa, the Americas, and Asia, their conception of the primitive, unconquered lands and peoples was based on highly sexualized imagery. “Romantic visions of the ‘virgin’ land of the Americas, the hypersexual African woman, and the lush sexualities of Pacific Islanders all shaped how European traders and conquerors understood and justified their imperial ventures” (Sreenivas 2014, 60), she explains. The military forces kept in the Indian subcontinent by the British East India Company relied on and exploited the sexuality and sexual labor of women in the subcontinent, who were seen as “highly serviceable” and provided British soldiers with both sexual and domestic services (Sreenivas 2014). Further, patterns of interracial intimacies and sexual relationships between imperial men and local women were fraught and varied throughout eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century colonial encounters across continents, Sreenivas explains. Sexuality and race were intertwined to render colonized non-European peoples as sexually perverse and racially degenerate.

Queer Nature

by Mateo Rosales Fertig

Queer Nature, co-created by Pinar and So Sinopolous-Lloyd, is a skillshare, education, and social-support organization based in the Pacific Northwest. They facilitate and help create workshops, spaces, and multiday immersive events for 2S (Two-Spirit) lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) people and queer and trans people of color (QTPOCs).

In these events, Pinar and So seek to create “narratives of belonging for folks who have often been made to feel by systems of oppression that they biologically, socially, or culturally don’t belong.” They focus on remembering the history of colonialism and environmental harm and centering the experiences of Indigenous peoples and their relationships with lands. Queer Nature offers events and classes on nature connection and place-based skills and studies, including tracking, handcrafts, queer wilderness project skillshares, workshops on the ecology of power and privilege, and queer stealthcraft. Queer Nature can be found on Instagram: @queernature.

Anti-Blackness and Chattel Slavery

Black women’s bodies and sexualities have been historically objectified by and for the colonial European gaze. Hortense Spillers describes how during the transatlantic slave trade the enslaved Black body became “the source of an irresistible, destructive sensuality” (Spillers 1987, 67) devoid of any humanity (Wynter 2003). The rendering of Black bodies as “chattel” was executed through the process of “ungendering” (Spillers 1987), which collapsed the male and female genders together and rendered nonexistent any possibility of personhood, desire, sexuality, embodied relationships, and familial kinships (Spillers 1987). In such an arrangement the captive Black woman’s body no longer retains her gender, sex, and sexuality—what Spillers calls the “customary lexis of sexuality including ‘reproduction,’ ‘motherhood,’ ‘pleasure’” (76).

The “deviant” sexualities of the Black body rendered it the non-white “other” under slavery and reduced it to the state of being a “commodity” (Hartman 2008) and nonhuman “flesh” (Spillers 1987) existing at a nexus of a racial inferiority and sexual perversion mapped onto Black people and the lands from which they were stolen. “Pornotroping,” which Spillers (1987) describes as a process of objectification, rendered the Black body a site of fantasy and “powerlessness.” Amber Jamilla Musser (2018) writes that pornotroping “violently reduces people into commodities while simultaneously rendering them sexually available.” Yvette Abrahams argues that there was an overlap between the periods of heightened pornotroping of KhoiSan women and the slavery of KhoiSan peoples in South Africa (1998, 220-36, 223). And it was around this time that Sara Baartman, a KhoiSan woman, was taken to Europe in 1810 to be exhibited before audiences to highlight her bodily features. Abrahams (1998) further argues that prior to the exhibition of Baartman, expositions and representations of the “savage” did not explicitly show women or Black sexuality.

With the exhibition of Baartman, the “connection between bestiality and unbridled sexuality was made explicit,” and it became impossible to separate Baartman’s sexualization from her public representation (Abrahams 1998, 226). “Freak shows” during this period, such as the ones in which Baartman was forced to participate, functioned as a site where the savage became equated with “raw sexuality” (Abrahams 1998) and the colonizer-colonized binary also acquired a sexualized, gendered, and racialized form with her embodiment, which stood in contrast with white femininity. Christina Sharpe, Yvette Abrahams, and other Black feminist scholars urge that we see how much of the writings about Baartman show too much of a focus and obsession on her bodily features. The repeated circulation of her images and narratives about her life continue to generate “a certain prurient pleasure” (Sharpe 2010). The story of Baartman has been removed from its histories and historiographic contexts, placed outside of it, completely isolating her from the world and times in which she lived (Abrahams 1998).

Using the example of how enslaved Black women’s bodies were used by plantation doctors for gynecological experiments, Snorton (2017, 52) describes chattel slavery as “a cultural apparatus that brought sex and gender into arrangement” where Black flesh became the “instrument” for that apparatus.

Caste and Sexuality

In other colonies—for example, in the Indian subcontinent—sexuality was shaped along the axes of not only race, religion, and class, but also caste. Precolonial domestic arrangements around sexuality and intimacy were changed by imperial policies, both through government intervention as well as missionization.[4] The family model of heterosexual conjugal domesticity was held up by missionaries and imperial administrations, viewing other forms of kinships, including polygyny and polyandry,[5] as perverse and nonnormative. Heterosexual patriarchal authority was upheld as the structural norm that decided familial arrangements, labor patterns, distribution of economic resources, and so on (Sreenivas 2014). For example, missionaries upheld heterosexual, monogamous marriages as the ideal, civilized institution, and along with this there was a clear, gendered division of domestic roles and labor. Women were to perform their wifely duties of taking care of the home, whereas economic activities and outdoor work were the responsibility of men, an arrangement developed in the West as a result of the industrial revolution was brought into the colonies. In colonial Nigeria, for example, wives played the central economic roles in families, a focal point that shifted toward men being at the center as a result of colonial rule. Men belonging to the colonized elite echelons of society benefited from the assumption of such colonial patriarchal authority. While working with the colonial government, native elite men along with colonial authorities gained patriarchal control over women’s sexualities as well as alternative sexualities (Sreenivas 2014).

Nishant Upadhyay has argued that connections between heteropatriarchal power and sexuality need to also take into account caste practices within both the geographical region constituting colonial and precolonial South Asia as well as within the South Asian diaspora. The connection between caste mobility and the control over women’s sexuality predates colonialism and conversations about race and gender, and formations of gender hierarchies during colonialism should also be informed by caste and caste-based sexualities (Chandra 2011, 127-53). We must complicate the colonizer-colonized binary by analyzing how caste power shaped “heteronormative sexual contracts” in these local contexts as well as the interactions between the colonizer and the colonized (130). Produced at the nexus of coloniality and caste, there was a rise in Brahmin hegemonic power, which in the late nineteenth century created “new patriarchies of caste Hindu society,” pushing prostitutes and temple dancers into the margins because their nonnormative, nonreproductive sexual practices as prostitutes were seen as being outside of respectable, upper-caste Hindu femininity (Chandra 2011, 135).

Even after the colonial administrations physically withdrew from their colonies, laws criminalizing nonnormative sexualities continued to remain in effect in the “post-” colonial states until recently. For example, in the Indian subcontinent, Section 377, which is a colonial law that criminalizes homosexuality, was operational until the Indian Supreme Court overturned it in 2018 after years of court battles. Women’s sexuality is controlled by enforcing intracaste marriages to strictly maintain caste structures and upper-caste Brahmin supremacy (Upadhyay and Bakshi 2020). Upadhyay and Bakshi (2020) argue that it is impossible to achieve sexual/queer/trans liberations without dismantling upper-caste Brahmin cis-heteropatriarchy, colonialism, and Islamophobia. Grewal and Kaplan (2001) draw our attention to the tradition-modernity binary and the ways the United States and Europe are seen as liberal havens where people can find sexual freedom, whereas other countries, especially in the Global South, are sites of sexual oppression. Dominant discourses built on this binary often normalize dominant gender and sexual identities while completely erasing other, more local expressions. As Grewal and Kaplan (2001) suggest, “nation-states, economic formations, consumer cultures, and forms of governmentality all work together to produce and uphold subjectivities and communities” (670). Using the example of migration and refugee flows into the West, they suggest that particular types of mainstream discourses normalize narratives of traditional, backward rural subjects fleeing their repressive environments back home and looking for a sexually liberated modern West.

Sex Education around the World

by Shaina Khan

According to the United Nations, comprehensive sex education is a human right. The UN Population Fund defines comprehensive sex education as “a rights-based and gender-focused approach to sexuality education.” It occurs “over several years [and provides] age-appropriate information.”

Countries take different approaches to sex education, and sex ed can even vary from state to state within a country. In countries like China and Indonesia, schools aren’t required to teach sex ed. In some of those countries, rates of sexually transmitted infections and teen pregnancies are increasing, as parents often aren’t equipped to teach their children about sex, or they assume that schools cover sex education.

In a few countries, like Sweden and New Zealand, sex education is mandatory. The Netherlands engages all students in age-appropriate sex ed starting when they are 4 years old. Their program includes teaching not only about contraception, sexually transmitted infections, and reproduction, but also about consent and pleasure. In the United Kingdom, sex education became compulsory in 2020. The new curriculum is broad and includes topics like healthy relationships, online safety, and domestic abuse.

In parts of the United Kingdom, as in other countries like the United States, critics have thwarted attempts to teach about lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) sexuality and relationships. Although sex education is not compulsory in Nicaragua, many schools do discuss LGBTQI+ concerns. The Samaritan Project in Nicaragua also teaches boys about masculinity and how sexual harassment harms women.

Sex education can take different names. In Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, and other African countries, classes in “Life Skills Education” include topics related to sexual health and relationships. These kinds of indirect names for sex education can counter stigma in communities where sex and dating are taboo topics.

Sexual Expressions and Sexual Politics

We saw in the previous section how sexualities are connected with gender, race, colonialism, and caste. Sexualities need to be situated and understood through an intersectional perspective. Intersectionality is a framework that talks about how a person’s race, class, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability work together to produce their unique experiences based on their overlapping identities and social location. In particular, intersectionality helps us see ways Black women experience interlocking forms of oppression produced at the nexus of gender and race (Moraga and Anzaldúa 1983; Collins and Bilge 2016). Intersectionality has been described as an analytical framework, and its “historical arc” (Nash 2019, 77) includes Black feminist scholars Kimberlé Crenshaw, Patricia Hill Collins, and other feminists of color, including Gloria Anzaldúa and the Combahee River Collective. They argue that oppression is not a sum of simply these different factors, but complex interactions between them, situated within specific historical and cultural contexts. Applying an intersectional approach to understanding sexualities enables us to see how these different factors decide whether we are able to express our sexuality and have relationships based on our gender identity, sexual expressions, and social locations. The political and cultural contexts in which we live tend to also control and regulate whether our nonnormative family and/or kinship networks are validated on the basis of our gender and sexuality. The current politics of sexuality determine its social constructions.

Sexual norms and practices are shaped by a variety of histories, politics, and gendered expectations, producing cultural variations in the social construction of gender and sexuality worldwide. “Sexual scripts” (Pereira and Kandaswamy 2010, 168-94) are determined by the way power is distributed in different societies and how sexual and bodily autonomy is only selectively available to some but denied to marginalized communities. For example, the reproductive rights of women are tightly controlled by interlocking systems of power and oppression. Black women’s sexuality has been increasingly deployed as a tool to drive globalized capitalism and further white supremacy and rightwing attacks on the Keynesian welfare state (Ross 2017). Loretta Ross, a prominent activist in the reproductive justice movement, argues that racialized and misogynist discourses have historically vilified and pathologized Black women’s sexuality as reflected in popular discourses and understandings, and there is a need to deconstruct these discourses. Black women’s sexuality and reproductive rights need an intersectional analysis and cannot be understood with a single-axis approach. Ross (2017) asks that we center sexual freedom and bodily autonomy in envisioning an intersectional praxis of reproductive justice. The reproductive rights of Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) have historically been controlled by nation-states through forced sterilization programs.

Gender Reassignment Surgery

by Shannon Garvin

Gender reassignment surgery (GRS) allows a person to reconstruct their own body to reflect their gender. The reassignment, which is irreversible, consists of several individual surgeries, depending on which gender is being changed, and within those surgeries, several options are available, from cosmetic on the outside to fully functional. For now, GRS does not include the ability to bear children.

GRS is available in many countries of the world depending on local law. The European Union provides an information page. Access is extremely limited in Africa and parts of the Middle East. Iran has offered surgery for years, but there is controversy over its intentions, as it made homosexual men into women instead of integrating homosexuality into its culture. Currently, Thailand offers a number of destinations for surgery, which costs a fraction of what it does in the United States. As with any surgical procedure, GRS patients will remind anyone that research and learning about the reputation of a potential doctor is paramount. GRS is a politically hot issue in many countries but entirely accepted and commonplace in others. Blogs of patients and videos about the procedures share the stories of those who have transitioned to their own gender.

Another medical procedure that is important to discuss here is female genital cutting (FGC),[6] which is a culturally specific procedure practiced in a variety of locations around the globe. Female genital cutting involves the surgical removal of external genital organs for nonmedical reasons. It is a cultural practice in parts of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Although the procedure may not affect one’s ability to become pregnant, it puts women at high risk of complications and can even result in death during childbirth. FGC also causes severe short- and long-term health complications, including severe pain, hemorrhage, other genital problems, shock, and death, according to the World Health Organization (2020).

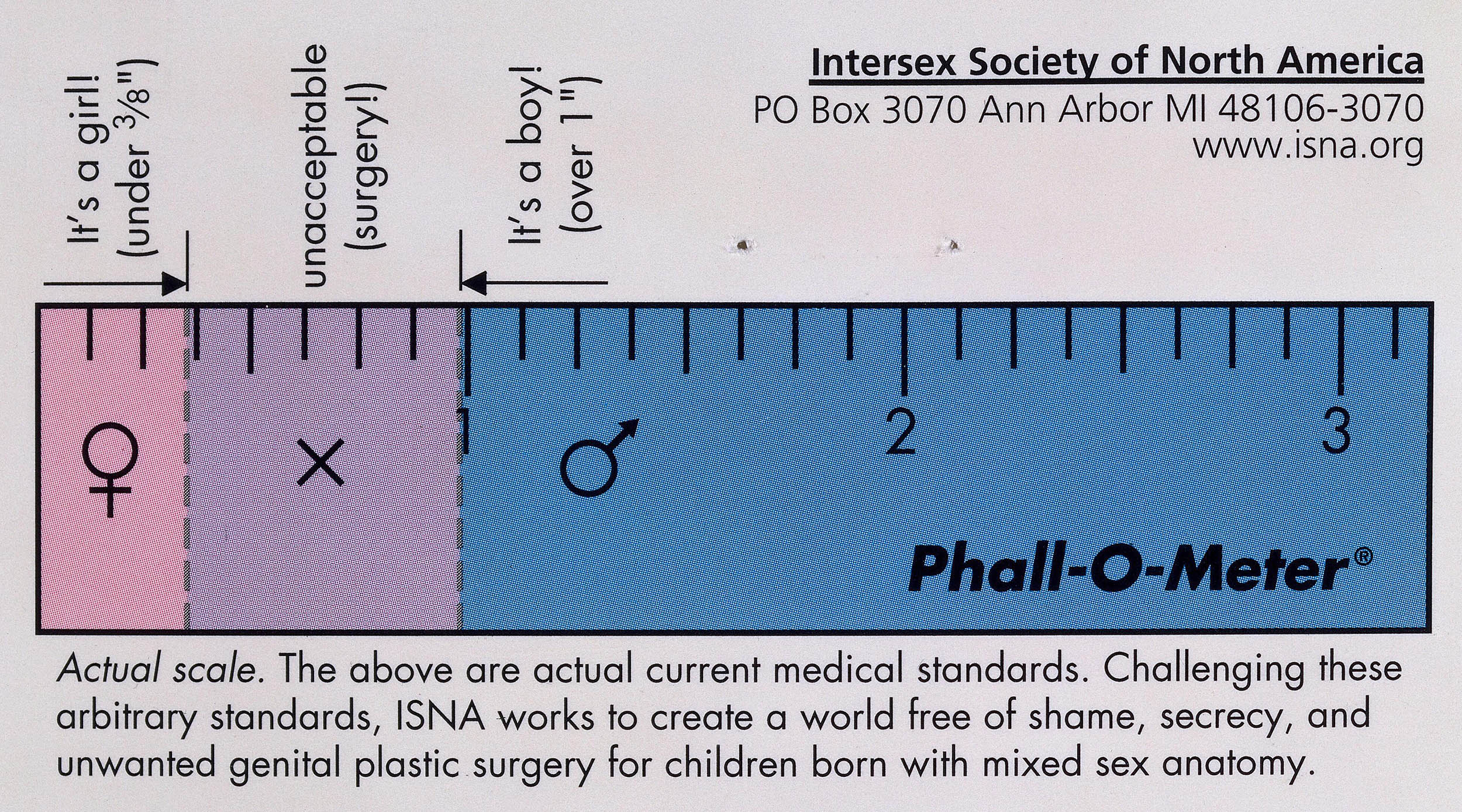

The World Health Organization (2020) describes female genital cutting in the context of the Global South as “inhuman,” “degrading,” and “cruel,” and “medical interventions” on children with intersex traits are framed and perceived as acceptable “corrective” procedures to “normalize” their bodily sexual development, which is pathologized and seen as anomalous within the western sex/gender binary. In the United States, children with intersex traits are forced into undergoing medicalized genital cutting; these medical procedures are often performed on infants, and thus consent is impossible to obtain. While non-western communities in the Global South and immigrant communities of color are vilified for subjecting their children to FGC, western parents often coerced by medical establishments into having their intersex children undergo surgeries are seen as having their children’s well-being in mind (Jafar 2019). The violent, gendered practice of FGC needs critical analysis that can challenge western-centric approaches in how popular discourses around it get framed. It is important to also understand that female genital cutting and “medical interventions” done on intersex children are not similar or equivalent procedures, but that looking at them closely allows us to see how the dominant discourses about these procedures are embedded in unequal power relations between the Global North and the South, where the North holds power to produce narratives and discourses about the Global South from its own viewpoint.

What Does “Intersex” Mean?

by Janet Lockhart

Intersex is a scientific term referring to a person whose biological sex differs in some way from what is considered clearly female or male. This may be due to variations present at birth in a person’s genes, chromosomes, or hormones, or it is sometimes caused by an environmental factor such as an endocrine disruptor (a natural or manufactured chemical that affects a body’s hormones). These variations may be visible in a person’s genitalia (external sex organs) or secondary sex characteristics (such as breasts and pubic hair), or they may be internal to the person’s body, such as their internal sex organs or hormones. Estimates are that about 2 percent of human beings have intersex characteristics.

“Intersex” does not necessarily describe a person’s gender identity—an intersex person may identify as female, male, nonbinary, or some other identity—or sexual orientation: a person with intersex characteristics may be gay, lesbian, straight, bisexual, or any of the other sexual orientations that occur in the human community.

Intersex people may, however, be affected by some of the same biases that affect people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+). They may also be affected by laws that prescribe how their identity is presented on documents and may struggle to access resources, such as health care, that respect their identity and their specific needs. Perhaps most difficult is the fact that many intersex people were and are subjected at birth or in infancy to surgeries to “correct” or “determine” their identity as clearly either female or male.

Organizations that support and advocate for intersex people include InterAct Advocates for Intersex Youth and the Organization Intersex International. Intersex Awareness Day is observed on October 26th.

The process of forced sterilization and other ways of covertly controlling sexuality is part of the lived reality of disabled people who are deprived of sexual and bodily autonomy. It is helpful here to look at the example of Ashley X, an American child who was born with static encephalopathy, which resulted in severe developmental disabilities. Ashley’s prognosis indicated that her disabilities would prevent her from having a “normal” quality of life, and her doctor suggested that removing her sexual and reproductive organs would “reduce her pain and discomfort” (Kafer 2013, 47). Because of her disabilities, Ashley was seen as having no gender, and the treatment courses suggested by her doctors through the years show the ways that the medical industrial complex sees disabled children as not requiring reproductive organs because not only do they lack sexuality, but also they should not be permitted to reproduce. Through hysterectomy and mastectomy, Ashley’s body was rendered small in size, flat-chested, and infertile, so that her physical and cognitive age could match and “reflect the lack of sexuality befitting a disabled person/baby” (Kafer 2013, 57). Kafer further argues that disabled people become completely disassociated with the possibility of sexual pleasure, indicated by the range of medical procedures that Ashley was made to undergo in order to control her sexuality. Disabled sexualities are seldom seen as positive or as something that can be “self-generated and self-directed” (2013, 65).

Pornography, Sexual Exploitation, and Globalization

In the previous sections, we saw how colonialism, imperialism, and globalization have historically affected sexualities worldwide. Globalization and capitalism under globalization and histories of imperialist exploitation of countries in the Global South have resulted in normalized hierarchies between economically advanced countries in the Global North and countries in the Global South. Globalization also determines how money and culture flow between these regions, reinforcing different economic and cultural hierarchies. This section explores the connection between neoliberal capitalist globalization and sexuality. It looks at the issues of popular culture and pornography to determine how they are shaped in complex ways by economic and cultural globalization.

Pornography is a contested site for feminist analysis. While degrading and hypersexualized imagery of women in popular culture like music and mainstream cinema is seen as a violation of their human rights, the self-sexualization of women of color in popular culture is also seen as their way of asserting their subjecthood and agency. In her work on the imagery of Black women in popular culture, Akeia A. F. Benard draws attention to the connection between colonially structured gender, race, sex, and class relationships and the ways they continue to exist under patriarchal capitalist structures in the present day. Benard argues that colonialism and globalized patriarchal capitalism, which are both instituted by white patriarchy, are not very different in how they exploit brown and Black women’s bodies for profit, and that the sex, sexuality, and the eroticism of women of color are all commodities that are considered to be always available and exploitable by white supremacist systems. There is also a fundamental difference in the way middle-class white women get to define and explore their sexuality, whereas Black women are “defined by their sexuality and as their sexuality” (Benard 2016, 3, emphasis original). Although white and Black women share patriarchal oppression, it is not only white patriarchy but also white women who benefit from the continued colonial exploitation of Black bodies, Benard writes.

Bernard (2016) also finds that pornography is a site where legacies of colonial oppression of Black women is clearly visible in the way their bodies are “bound, gagged, and/or in chains” (4), and along with Asian women, they are depicted as being docile and sexually submissive. The exploitation of Black women’s bodies in violent pornographic media, even if they are engaging in self-sexualization and self-marketing, is a type of symbolic and structural violence, which is in conflict with their sexual health, Benard writes. She frames “symbolic violence” (Bourdieu 1994) as “a form of domination that is exercised on social actors with their own involvement and complicity” that “operates under an illusion of choice” (Benard 2016, 2). The circulation of the hypersexualized imagery of Black women’s bodies takes place within a capitalist patriarchal system and is controlled by individuals and systems holding power. Women engaging in self-sexualization are committing structural violence, as they hold more power than their counterparts who might ultimately become victims of symbolic violence and “choose” to consume such cultural productions and mass media (Benard 2016).

Challenging readings of self-sexualizing women of color as completely lacking agency, Celine Parreñas Shimizu (2007) suggests that the “perverse sexuality” attributed to Asian American women could be a source of knowledge about their racialization and the subjectivity. She argues that the “pleasure and fantasy from the sexualization of race must be part of race politics” (6). Shimizu challenges western white feminists’ theorizing on Asian prostitutes, denying them voice, agency, and subjecthood, and argues that frameworks like sexual slavery are reductive. Mainstream representations of Asian American women are shaped by the histories of racialization and pathologization through immigration and exclusionary US policies. The sexualities of Asian American women were used as a weapon in order to render them without agency and keep them subjugated. Observing the representations of women of color in visual/public cultures helps us see the inseparability of race and sexuality, which are situated in complex histories of colonialism, and immigration law, and patriarchal capitalist presents.

hues and the Safe Zone Project

by Shannon Garvin

The Safe Zone Project (SZP) is one of the many educational and social justice resources that has been created by hues. “hues is a global justice collective of artists, educators, & activists. It was co-created in 2017 as a place for Sam Killermann’s creations & collaborations to live . . . We create art that inspires action, tools that facilitate change, and resources that bolster efforts for global justice–all embodied in the spirit of the gift.”

The Safe Zone Project is a two-hour curriculum that can be downloaded and used for free to educate and support “safe” spaces for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, and intersex plus (LGBTQI+) people. If you need help communicating or want to learn more, both the hues website and the SZP are excellent places to start. The websites are packed with information, resources, and links to other resources. Killermann relies on the support of patrons so that he can live out his desire for social justice. Access to economic resources creates barriers in nearly every part of our culture now—who can afford and who cannot afford to “buy.” With outside support, he removes the economic barriers and is able to offer, as a social activist, his gifts of art as socially just and available to all.

Pinkwashing and Radical Coalitional Futures

In the previous sections of this chapter, we saw how framing queer liberation and sexual freedoms within dominant institutions and inclusion-based approaches reinforces the power that these institutions already hold and wield. With the centrality of such LGBTQI+ rights-based and equality-based approaches, there has been a co-optation of queer social movements by dominant institutions—like conservative political parties, neoliberal capitalist institutions and organizations, and governments—toward corporate and/or political interests. Activists have described this process as “pinkwashing.” This term was first coined by Palestinian queer and trans activists while describing how the Israeli government promotes itself as being LGBTQI+ friendly while erasing and diverting attention away from its ongoing genocidal, settler-colonial projects on the Palestinian lands and peoples (“Pinkwatching Israel,” n.d.). Within this narrative, the Israeli nation-state also frames Arab and Muslim communities as being queerphobic, homophobic, and transphobic. More examples of pinkwashing include corporate organizations funding Pride marches, framing themselves to be LGBTQI+ friendly, and claiming to provide inclusive hiring and work environments while funding war and weapons, for example, indirectly endorsing human rights abuses in other locations around the globe (Miller 2019). The issue of marriage equality and gay and lesbian inclusion in the military are examples of pinkwashing (Spade 2015). More recently, trans politics and specifically the inclusion of trans people in the military is pinkwashing the US military. Allowing trans people to join the military, similar to marriage equality, produces a kind of narrow and highly visible agenda that creates advocacy for trans communities but does not stop police violence and brutality against them; nor address the precarity, houselessness, and health care crises they face; nor disrupt the military-imperialist interventions of the United States in different parts of the world; nor dismantle racist and xenophobic immigration and border control regulations (Spade 2015).

The issue of pinkwashing separates queerness from other identities, and sexuality from other intersecting dimensions of life and social inequalities, like gender, race, class, and (dis)ability. So, what is the way forward? Cathy Cohen’s work is useful in thinking about strategies to bridge these gaps and to think about radical coalitional work for the future. Cohen (1997) describes “transformational coalition politics,” which starts with destabilizing identity categories and identity-based politics that isolate only one aspect of a person’s identity. She asks that we challenge the binary between “heterosexual” and “queer” in a way that centers the intersectional workings of gender, race, class, and sexuality, which help make sense of the oppressions experienced by marginalized communities.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks editor Tracy R. Butts for her thoughtful and enriching reviews. Thanks are also due to committee chairs Mehra Shirazi and Qwo-Li Driskill for their feedback, support, and encouragement. The author also thanks dear intellectual sibling Lzz Johnk for their love, friendship, and generous feedback on this chapter.

Learning Activities

- When engaging in intersectional feminist analysis, western feminists sometimes focus on the intersections of gender, race, class, and sexuality without considering other axes of analysis. In this chapter, Kalyanam adds axes of analysis such as caste; histories of colonialism, chattel slavery, and/or genocide; geographic location (e.g., Global North / Global South); and (dis)ability to her discussion of sexualities worldwide. How do Kalyanam’s additions allow feminists to engage in more effective analyses of transnational feminist issues?

- Kalyanam describes cultural examples of gender and sexuality that “were outside of European, binary norms and understandings and were framed as deviant or perverse,” such as Two-Spirit and joyas in North America and hijiras in the South Asian subcontinent. What do you know about Two-Spirit communities, joyas, and hijiras? Working alone, with a partner, or in a small group, choose one of these topics and take a few minutes to conduct some online research. What do you learn? How are/were people who identify as such framed as “deviant or perverse”? How might the existence of such peoples challenge European heteropatriarchal norms for gender and sexuality?

- Kalyanam discusses the relationship between female genital cutting (FGC) and “medical interventions” on intersex children. She argues, “The violent, gendered practice of FGC needs critical analysis that can challenge western-centric approaches in how popular discourses around it get framed. It is important to also understand that female genital cutting and ‘medical interventions’ done on intersex children are not similar or equivalent procedures, but that looking at them closely allows us to see how the dominant discourses about these procedures are embedded in unequal power relations between the Global North and the South, where the North holds power to produce narratives and discourses about the Global South from its own viewpoint.” Take a look at discussions of FGC and “medical interventions” of intersex children online. How are such conversations framed? Are the two ever considered in relation to each other? How might Kalyanam’s argument transform the discussion about these practices, both separately and in relationship to each other?

- How does Kalyanam define pinkwashing? What examples does Kalyanam use to support her arguments? What additional examples of pinkwashing can you provide?

- Working in a small group, add these key terms to your glossary: Two-Spirit, settler-colonialism, Global North / Global South, First World / Second World / Third World, pinkwashing, heteropatriarchy, heteronormativity, white supremacy, genocide, binary, cisgender, transgender, compulsory heterogenderism, prison industrial complex, nonprofit industrial complex, hijras, joyas, pornotroping, Keynesian welfare state, transformational coalition politics.

References

Abrahams, Yvette. 1998. “Images of Sara Baartman: Sexuality, Race, and Gender in Early-Nineteenth-Century Britain.” In Nation, Empire, Colony: Historicizing Gender and Race, edited by Ruth Roach Pierson, Nupur Chaudhuri, and Beth McAuley, 220–36. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. 2013. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy.” Feminist Formations 25, no. 1, 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/ff.2013.0006.

Benard, Akeia A. F. 2016. “Colonizing Black Female Bodies within Patriarchal Capitalism: Feminist and Human Rights Perspectives.” Sexualization, Media, and Society 2, no. 4, 2374623816680622. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374623816680622.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1994. “Structures, Habitus, Power: Basis for a Theory of Symbolic Power.” In Culture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social Theory, edited by Nicholas B. Dirks, Geoff Eley, and Sherry B. Ortner, 155–99. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chandra, Shefali. 2011. “Whiteness on the Margins of Native Patriarchy: Race, Caste, Sexuality, and the Agenda of Transnational Studies.” Feminist Studies 37, no. 1, 127–53.

Chrystos. 1993. In Her I Am. Vancouver, BC: Press Gang.

Cohen, Cathy J. 1997. “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 3, no. 4, 437–65. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3-4-437.

Collins, Patricia Hill, and Sirma Bilge. 2016. Intersectionality (Key Concepts). Cambridge, MA: Polity, 2016.

Driskill, Qwo-Li. 2004. “Stolen from Our Bodies: First Nations Two-Spirits/Queers and the Journey to a Sovereign Erotic.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 16, no. 2, 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1353/ail.2004.0020.

———. 2016. Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Friedman, Susan Stanford. 2015. Planetary Modernisms: Provocations on Modernity Across Time. New York: Columbia University Press.

Grewal, Inderpal, and Caren Kaplan. 2001. “Global Identities: Theorizing Transnational Studies of Sexuality.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 7, no. 4, 663–79. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-7-4-663.

Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

Hinchy, Jessica. 2019. Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India: The Hijra, c.1850–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hossain, Adnan. 2018. “De-Indianizing Hijra: Intraregional Effacements and Inequalities in South Asian Queer Space.” Transgender Studies Quarterly 5, no. 3, 321–31.

Jafar, Afshan. 2019. “The Thin Line between Surgery and Mutilation.” New York Times. May 2, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/02/opinion/fgm-ruling-intersex-surgery.html.

Jamilla Musser, Amber. 2018. Sensual Excess: Queer Femininity and Brown Jouissance. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Kafer, Alison. 2013. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Miller, Phil. 2019. “Outrage as Pride Accused of ‘Pinkwashing’ Bomb Company.” Morning Star, August 9, 2019. https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/b/pride-accused-pinkwashing-bomb-company-arms-homophobic-regimes.

Miranda, Deborah A. 2010. “Extermination of the Joyas: Gendercide in Spanish California.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16, no. 1–2, 253–84.

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. 1997. “Women Workers and Capitalist Scripts: Ideologies of Domination, Common Interests, and the Politics of Solidarity.” In Feminist Genealogies, Colonial Legacies, Democratic Futures, 1st ed., 3-29. New York: Routledge.

Moraga, Cherrie, and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds. 1983. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, 2nd ed. Latham, NY: Kitchen Table / Women of Color Press.

Nash, Jennifer C. 2019. Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality. Next Wave. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv111jhd0.

Nicolazzo, Z. 2017. “Compulsory Heterogenderism: A Collective Case Study.” NASPA Journal about Women in Higher Education 10, no. 3, 245–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407882.2017.1351376.

Pereira, Charmaine, and Priya Kandaswamy. 2010. “Sexualities Worldwide.” In Women Worldwide: Transnational Feminist Perspectives on Women, 168–94. New York: McGraw Hill.

Picq, Manuela L. 2020. “Decolonizing Indigenous Sexualities.” In The Oxford Handbook of Global LGBT and Sexual Diversity Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190673741.013.23.

Pinkwatching Israel. n.d. Pinkwashing Israel website. Accessed February 26, 2021. http://www.pinkwatchingisrael.com/.

Ross, Loretta J. 2017. “Reproductive Justice as Intersectional Feminist Activism.” Souls 19, no. 3, 286–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999949.2017.1389634.

Sharpe, Christina. 2010. Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects. Perverse Modernities. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Shimizu, Celine Parreñas. 2007. “The Hypersexuality of Asian/American Women: Toward a Politically Productive Perversity on Screen and Scene.” In The Hypersexuality of Race: Performing Asian/American Women on Screen and Scene, 1–29. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Shoemaker, Nancy. 2015. “A Typology of Colonialism.” Perspectives on History. October 1, 2015. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/october-2015/a-typology-of-colonialism.

Smith, Andrea. 2016. “Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy: Rethinking Women of Color Organizing.” In Color of Violence: The INCITE! Anthology, edited by INCITE! Women of Color against Violence. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Snorton, C. Riley. 2017. Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Spade, Dean. 2015. Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Spillers, Hortense J. 1987. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17, no. 2, 65–81.

Sreenivas, Mytheli. 2014. “Sexuality and Modern Imperialism.” In A Global History of Sexuality: The Modern Era, 57–88. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

Upadhyay, Nishant. 2020. “Hindu Nation and Its Queers: Caste, Islamophobia, and De/Coloniality in India.” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 22, no. 4, 464–80.

Upadhyay, Nishant, and Sandeep Bakshi. 2020. “Translating Queer: Reading Caste, Decolonizing Praxis.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation, Feminism and Gender, 1st ed., 336–44. London: Routledge.

Warner, Michael. 1993. Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4, 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

World Health Organization. 2020. “Female Genital Mutilation.” Accessed December 7, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation.

Wynter, Sylvia. 2003. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3, 257–337.

Image Attributions

4.1 “Hijras in Laxman Jhula” by Quixosis is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

4.2 “Two Spirit Society of Denver” by iagoarchangel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

4.3 “Campaign to stop Female Genital Mutilation” by UNAMID Photo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

4.4 “‘Phall-O-meter’, Intersex Society of North” is licensed under CC BY 4.0

4.5 “Orange The World 2016 – Jordan” by UN Women Gallery is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

4.6 “No Pinkwashing Bus Shelter” by TruthForceinSF is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

- The term Third World has been reclaimed by feminists from formerly colonized places. The term is considered problematic and outdated, and it does not adequately address the social, political, economic, racial, cultural differences within the regions that are a part of it. Mohanty argues that despite its shortcomings, Third World carries a “heuristic value and explanatory specificity in relation to the inheritance of colonialism and contemporary neocolonial economic and geopolitical processes that the other formulations lack” (Mohanty 1997, 7). The other formulations Mohanty is referring to here are the Global North and South, as well as developed nations, developing nations, and underdeveloped nations. ↵

- he terms Global North and Global South emerged from the Brandt Line during the 1980s, which delineated the globe into the North and the South based on their economic status. The Global North was relatively richer, and the Global South consisted of poorer nations. These terms initially replaced “developed” and “developing” nations but have been problematized for the way they erase local specificities and do not acknowledge histories of colonialism and how it operated to create inequal distribution of resources and power between imperial metropoles and colonies. Susan Friedman writes in Planetary Modernisms, “Although rhetorically spatial, these terms are as geographically imprecise and ideologically weighted as East/West. Akin to the West, the Global North signifies modern global hegemony; the Global South (which includes many countries north of the equator) indicates the subaltern, that is, the unmodern or still modernizing Rest—a binary construction that continues to place the West at the controlling center of the plot” (Friedman 2015, 123). ↵

- Hijras are a “publicly institutionalized subculture” (Hossain 2018, 1) of people in South Asia assigned male at birth and are sex-/gender-nonconforming, feminine-identified, and live in structured communities of acquired kin. ↵

- Missionization is the practice of religious missionary work, and in this context, it refers specifically to the work of Christian missionaries who played important and sometimes central roles in projects of colonialism around the world. Through missionization, colonized peoples’ religious, cultural, and faith-based practices were rendered savage and destroyed as Christianity was imposed. In addition to churches, missionary schools were also key institutions that furthered projects of missionization, which also went hand in hand with the implementation of English language. ↵

- Polygyny is the practice where a man has multiple romantic and/or sexual partners, whereas polyandry is the practice where a woman has multiple romantic and/or sexual partners. ↵

- Female genital cutting is the collective name for a number of procedures and operations performed to partially or totally remove the external genitalia or injuries to the genital organs. These operations are not medically necessary. ↵