Global Politics of the Body

Tracy Butts

The concept of body politics may be unfamiliar to those who are new to the discipline of women’s and gender studies. In essence, body politics issues are at the center of individual, societal, and political struggles to claim control over one’s own biological, social, and cultural “bodily” experiences. As a result, “the powers at play in body politics include institutional power expressed in government and laws, disciplinary power exacted in economic production, discretionary power exercised in consumption, and personal power negotiated in intimate relations” (Shaw 2021). The events of 2020, particularly the COVID-19 global pandemic and US presidential election, with its hot-button issues, have been the impetus for worldwide conversations about the ways in which human bodies are understood, governed, and used as sites of resistance.

Discussions about body politics during this time have revolved around the death of US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, reproductive rights and freedoms, and women’s health; immigration and the separation of parents and children at the border; police- and state-sanctioned acts of violence; anti-Black racism and Black Lives Matter protests; sexual identities; and identity politics.

Femicide in Turkey

by Lauren Grant

In July 2020, 27-year-old Pinar Gültekin was found murdered by her ex-partner. Gültekin’s death, amid a growing wave of awareness and protests to combat violence against women, sparked outrage across Turkey and the world. As activists took to the streets, often they were met with further violence, where officers intervened with brutal force to quash protests. Gültekin’s death increased national and international recognition of the systemic problem of femicide (murder of women). Calls for justice quickly moved beyond this incident, citing the increasing rates of violence against women perpetrated with impunity in Turkey and across the world.

As women’s rights activists have evidenced, both in street protests and viral social media campaigns, femicide forms “part of a larger pattern that has been emerging in Turkey under the country’s increasingly authoritarian Justice and Development Party (AKP) government.” Since 2010, “more than 3,000 women have been murdered as a result of male violence,” most commonly because of women’s attempts to make decisions about their own lives or resistance to coercive control within relationships, “with the figure more than doubling over the years.” The sociopolitical, patriarchal, and religious norms that dominate women’s lives and confine their roles to the family are the root cause of persistent and increasing rates of femicide. A 2009 study conveyed that upward of 42 percent of Turkish women aged 15-60 had suffered from physical or sexual violence at the hands of their intimate partners.

Amid increasing rates of violence, Turkish activists have demanded furtherance of the Istanbul Convention (2011), the Council of Europe’s leading treaty on violence against women, including domestic violence. While the doctrine has been championed for its “progressive” approach to combating violence against women, the convention fails to mention “femicide” at all, a major concern. Further, in March 2021 the AKP withdrew from the convention, casting women’s lives, safety, and rights out of legal, protectionary reach, in defiance of Turkey’s legal obligations under international human rights law.

Anti-femicide movements in Turkey and elsewhere have highlighted how femicide occurs within a framework of patriarchal oppression. Femicide too often entails sexual violence, coupled with the brutal mutilation of women’s bodies after they are murdered. The permittance of its occurrence and the absence of justice serve as public displays of the politics of the female body.

Femicide is genocide against women, and the failure of states, including Turkey, to punish perpetrators for the crime unveils how femicide “entails a partial breakdown of the rule of law because the state is incapable of guaranteeing respect for women’s lives and human rights.” While the state has proven an impediment to safeguarding women’s rights, activists in Turkey and across the globe are leading a transformative movement that interrogates the politics behind femicide, standing up against the practice and the impunity that sustains it.

The human body is coded with meaning and significance. It yields insight into not just how we see ourselves but also how others see and ultimately understand us. Because our identities are read from our bodies, superficial physical characteristics—eye shape, hair texture, skin tone and complexion, and body shape—are used to divide and classify us into socially constructed racial groups. Within these groups, we are further divided and classified again based upon constructs such as class, gender, sexual identity and expression, age, religion, nationality, and ability. Consequently, we subscribe meaning to human bodies based upon our perceptions and interpretations of each of these groupings and subgroupings, where we are socialized and taught how to perform as members of the various communities to which we belong, through body rules—“implicit and explicit norms, standards, and socially enforced expectations for presenting and using bodies” (Otis 2016, 160). For example, in some communities, female pubic hair is frowned upon, viewed as unsightly and unsanitary. Therefore women who shave signal their conformity to this body rule, and those who do not shave signal their refusal to conform to the norm, for “the body is read as a sign of one’s commitments to diet, lifestyle, fashion, and consumption. As the body signals the self, its priorities, ethics, morals, and health, its surface becomes a means of displaying such commitments” (Otis 2016, 160). The body groupings are hierarchical in nature, whereby individuals belonging to the dominant groups (i.e., white, male, able-bodied, cisgender) are afforded the most power and privilege. As individual bodies move further from the center, meaning the more they differ from the norm, they are afforded less and less power and privilege.

In studying body politics, contemporary feminist scholars build upon the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault (1977) and American philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler (1993), whose works focus on the relationship between the body, power, and sexuality and the performative nature of gender and sex, respectively. Yet body politics have existed for as long as people have been embodied. Former slave, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth provides an insightful case study on body politics. In 1851, Truth delivered her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The text of her speech and the narrative around its delivery reveal how Truth’s racialized and gendered body was governed, perceived, and othered. In the speech, reported in the June 21, 1851, edition of the Anti‐Slavery Bugle by Marius Robinson, Truth acknowledges the oppositional thinking about men and women and confronts the myth that women are inferior to men based upon their perceived lack of physical strength and mental acumen:

I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now.

As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart — why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, — for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seems to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble.

Truth’s speech also calls attention to the ways in which her Black female body is othered and not afforded the power and privileges given to white women and men, despite the fact that she does the work assigned to both groups. Moreover, Truth asserts that the granting of equal rights is not a zero-sum game, but rather an act that benefits everyone and poses no threat to the rights of men.

Feminist and abolitionist Frances Gage imposes her perceptions of Truth’s Black body on her recounting of the speech in 1863. For one, Gage uses a Southern dialect to reflect Truth’s speech and possibly Truth’s illiteracy: “Well, chillen, what dar’s so much racket dar must be som’ting out o’kilter. I tink dat ’twixt de [negroes] of de South and de women at de Norf, all a-talking ’bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking ’bout? Dat man ober dar say dat woman needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted ober ditches, and to have de best place eberywhar.” In reality, Truth spoke with a Dutch accent, and though she never learned to read or write, Truth was well educated. Gage also focuses on Truth’s bodily frame, describing her “almost Amazon form, which stood nearly six feet high” and her right arm with “its tremendous muscular power.” Conjuring up imagery of the plantation mammy, Gage characterizes Truth as a savior and a protector, for just when “some of the tender- skinned friends were on the point of losing dignity, and the atmosphere betokened a storm,” Truth spoke out. In doing so, Gage posits that Truth “had taken us up in her strong arms and carried us safely over the slough of difficulty turning the whole tide in our favor.” Gage’s fictionalizing of the text and events of the day reveals her inability to see Truth beyond her own perceptions of the identities mapped onto Truth’s body and dismisses Truth’s own account of her vulnerabilities as a Black woman as well as her relegation to a third-class citizenry (Sojourner Truth Memorial Committee, n.d.).

Feminist scholarship on the subject of body politics reveals that “bodies are powerful symbols and sources of social power and privilege on one hand and subordination and oppression on the other” (Waylen et al. 2013). Gage’s treatment of Truth helps us to better see the development and evolution of feminist thought on the subject of bodies as well as the areas where it continues to falter, particularly with regard to race and ethnicity. March 2020 saw the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Our Bodies, Ourselves, referred to in some circles as the “feminist ‘Bible of women’s health’” (Davis 2002, 224). In 1969, a group of women, mostly young, white, middle class, and college educated, met in a workshop on “Women and Their Bodies,” where they talked about issues of sexual and reproductive health. That group eventually morphed into the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (BWHBC) and gave birth to “Women and Their Bodies,” a 193-page course book published in 1970, reissued a year later as Our Bodies, Ourselves “to emphasize women taking full ownership of their bodies” (Our Bodies, Ourselves, n.d.). Since that time, the book has been updated and revised nine times, most recently in 2011, has sold more than 4 million copies, has been named one of the best hundred nonfiction books (in English) by Time magazine, and has been reproduced in thirty-three languages.

But the project has also been met with criticism, namely that “‘global feminism’ is little more than an imperialistic move by primarily white, middle-class US feminists to establish their brand of feminism as universal, while ignoring the experiences, circumstances and struggles of women in other parts of the world” (Davis 2002, 240). Upon the insistence of “Black, Latina, Native American, and Asian feminists . . . that an inclusive feminism examine and redress the historic evaluations of bodily difference that structured oppression of women according to race” (Shaw 2021), Our Bodies, Ourselves transitioned from translations and adaptations to “inspired” versions that were grounded in a country’s cultural exigencies as is the case with the Indian, South African, and Egyptian versions. The BWHBC’s main concern was to ensure that feminists would have editorial control over the translation and could adapt the book to fit their own social, political and cultural context” (Davis 2002, 230).

Posture as Peace and Power

by Shannon Garvin

The placement and posture of our physical bodies hold great power. Since the majority of communication is through nonverbal cues, the look on our face or the way we hold ourselves tells others a lot about what we are thinking and intending to do.

In July 2016, Ieshia Evans, a licensed practical nurse from Pennsylvania, traveled to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, following the shooting death of Alton Sterling by police. Witnesses describe her calmly walking into the center of the road being blocked and cleared by police officers in riot gear, her outer serenity reflecting her inner belief in the rights of all people. In an incident lasting a mere thirty seconds, she was arrested by police for standing in the road. Reuters photographer Jonathon Bachman caught the stunning photo of the encounter as she stands upright, her dress billowing in the wind, and multiple officers in full riot gear rush her.

Alex Haynes, a friend of twenty years, said that Evans traveled to Baton Rouge “because she wanted to look her son in the eyes to tell him she fought for his freedom and rights.” Many moments in history carry iconic images that pierce our souls and capture our imagination for a better world. The presence and poise of Iesha Evans provided one of the lasting images of the Black Lives Matter protests and hope for a more equitable future as we see a lone woman speaking truth to power with her body.

US feminists of color “objected to the narrow construction of gender politics by white feminists, and they moved to include the differences that race, class, and sexuality make in women’s position in society” (Shaw 2021). A decade after the publication of Our Bodies, Ourselves, feminists of color produced This Bridge Called My Back, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa. In the preface to the fourth edition, published in 2015, Moraga writes,

The first edition of This Bridge Called My Back was collectively penned nearly thirty- five years ago with a similar hope for revolutionary solidarity. For the first time in the United States, women of color, who had been historically denied a shared political voice, endeavored to create bridges of consciousness through the exploration, in print, of their diverse classes, cultures and sexualities.

In 1982, Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith edited All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women Studies (2015). The editors speak to the necessity of the book in its introduction:

The political position of Black women in America has been, in a single word, embattled. The extremity of our oppression has been determined by our very biological identity. The horrors we have faced historically and continue to face as Black women in a white-male dominated society have implications for every aspect of our lives, including what white men have termed “the life of the mind.”

Both of these books, much like Our Bodies Ourselves, signaled the critical need for feminist scholarship that more thoughtfully and thoroughly examined the intersections of race and gender.

Sandra Cisneros highlights how our bodies serve as markers of our status and power in “Those Who Don’t,” the twelfth chapter of her short-story cycle The House on Mango Street (1984):

Those who don’t know any better come into our neighborhood scared. They think we’re dangerous.

They think we will attack them with shiny knives. They are stupid people who are lost and got here by mistake. But we aren’t afraid. We know the guy with the crooked eye is Davey the Baby’s brother, and the tall one next to him in the straw brim, that’s Rosa’s Eddie V., and the big one that looks like a dumb grown man, he’s Fat Boy, though he’s not fat anymore nor a boy.

All brown all around, we are safe. But watch us drive into a neighborhood of another color and our knees go shakity-shake and our car windows get rolled up tight and our eyes look straight. Yeah. That is how it goes and goes. (28)

In the passage quoted above, Esperanza, Cisneros’s young Chicana protagonist, shares how outsiders perceive her predominately Latinx and working-class neighborhood as being dangerous, yet she feels safe there, at home, among people who look like her. But Esperanza also suggests that this fear of the other is universal, for members of her community feel unsafe when they venture into “a neighborhood of another color,” which for those groups is seen as safe and comforting but can feel dangerous for individuals outside of their community.

Ultimately, this chapter leads us to the understanding of how “the body becomes the basis for prejudice, but [it] is also through the body, its appearance, and behavior that prejudice can be challenged” (Cele and van der Burgt 2016).

Nalgona Positivity Pride

by Mateo Rosales Fertig

Nalgona Positivity Pride, or NPP, is an eating disorder education organization that focuses on body positivity and connection with community. Ingrained in “Xicana Indigenous feminisms and DIY punx praxis,” NPP seeks to raise awareness of eating disorders and the influences of colonialism on body image in Black and Indigenous communities of color. They educate folks about the connection between ancestral trauma and disordered eating, teach harm-reduction practices, and focus on the specific needs of Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC). They do this educational work and community support through a mix of digital media, discussion and support groups, grassroots treatment models, and art.

NPP’s goal is to make space for healing opportunities by and for Black and Indigenous communities of color. They also organize the Mujeres Market, where the work of women, queer and trans artists, and creators of color celebrate each other’s artistry and hustle and sell their work through a pop-up community market in several cities in Southern California. NPP can be found on Instagram: @nalgonapositivitypride.

Much like where a person lives, items such as clothes, hairstyle, language, behavior, and bodily appearance/size can be used to interpret a person’s socioeconomic status, political affiliation, and their commitments. For example, consider the red Make America Great Again (“MAGA”) hat, colored and braided hair, and Kim Kardashian’s derriere, which rivals the reality television star in popularity. The red MAGA hat worn by supporters of former US president Donald J. Trump signals the wearer’s political affiliation. The hat informs other Trump supporters they are in the presence of someone who shares their political leanings and gives the feeling of a political mass, thereby lending credence to their claim of belonging to a “silent majority.” To Trump opponents, conclusions can be drawn about the wearer’s stance on a number of social issues—anti-abortion, anti-immigration, anti-marriage equality, anti-social welfare programs, anti-political correctness, anti-feminist, and so on.

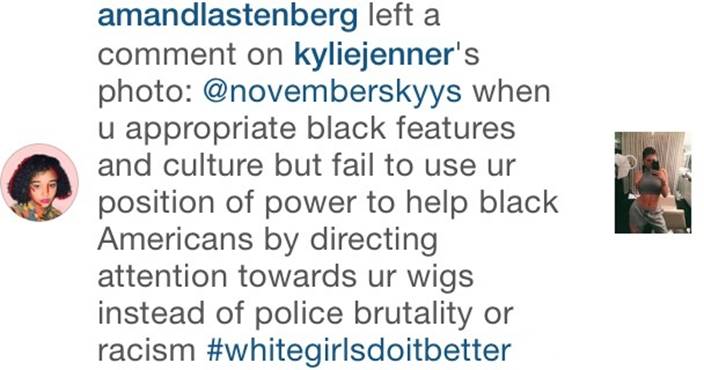

The current fashion trend of women dyeing their hair with bright pastels and neon colors gets read differently depending upon the race/ethnicity of the wearer. Black women wearing brightly colored hair are often labelled as “ghetto,” a term loaded with meaning about class, or lack thereof, and is often code for Black itself. Yet white women with colorful hair are often hailed as trendy, edgy, and daring. Kylie Jenner received similar praise back in 2015 when she posted a photo to Instagram of herself wearing her hair in two braids. Hunger Games actress Amandla Stenberg took the younger Kardashian sibling to task, pointing out the double standard from which Jenner benefits as well as her hypocrisy: “when you appropriate black features and culture but fail to use ur position of power to help black americans by directing attention towards ur wigs instead of police brutality or racism #whitegirlsdoitbetter” (Stenberg 2015).

The current fashion trend of women dyeing their hair with bright pastels and neon colors gets read differently depending upon the race/ethnicity of the wearer. Black women wearing brightly colored hair are often labelled as “ghetto,” a term loaded with meaning about class, or lack thereof, and is often code for Black itself. Yet white women with colorful hair are often hailed as trendy, edgy, and daring. Kylie Jenner received similar praise back in 2015 when she posted a photo to Instagram of herself wearing her hair in two braids. Hunger Games actress Amandla Stenberg took the younger Kardashian sibling to task, pointing out the double standard from which Jenner benefits as well as her hypocrisy: “when you appropriate black features and culture but fail to use ur position of power to help black americans by directing attention towards ur wigs instead of police brutality or racism #whitegirlsdoitbetter” (Stenberg 2015).

Similarly, Jenner’s older sister Kim Kardashian has literally built her career on her backside. Her posterior, which has been said to have broken the Internet, is a point of pride and the topic of much discussion, cementing Kardashian’s status as a sex symbol. Yet the irony of Kardashian’s celebrity and fame for the very attribute for which Black women have been labeled animalistic, bestial, and freakish is not lost on Black women (Butler 2014). What is even more ironic is the fact that many Black women are naturally, to quote Destiny’s Child, “bootylicious,” whereas Kardashian has been dogged by rumors that her rear end has been cosmetically enhanced— again, pointing to a double standard in the treatment of Black and white women.

Does Clean Have a Color?

by Sarah Baum

One of the longest racist themes in advertising, and seemingly one of the most difficult prejudices to remove, is the idea that whiteness is equal to cleanliness and purity. Soap and other cleaning products became linked with the idea that white was pure and anything not white was dirty. The early advertisements for Ivory soap often featured racist stereotypes that went well beyond the idea of white being clean to display black as being dirty, not just in clothing but also in shades of skin.

This theme should have been left to the pages of history decades ago, but the simple concept of clean having a color continues to reappear in modern advertising. A recent television commercial in China portrayed an African man flirting with a fair-skinned Asian woman; they approach each other, and then she suddenly stuffs a detergent pod into his mouth before forcibly shoving him into a washing machine. When he emerges, not only are his clothes clean, but he’s now a light-skinned Asian man who winks at the camera.

Even the best of intentions often fail as advertisers trip over this old bigotry. An ad for Dove soap featured a Black woman in a darker-toned shirt; she removed the shirt to revel a fair-skinned white woman in a light-colored shirt underneath. Dove meant to promote diversity and instead fell into this old racist theme. What’s even worse, in the case of the Chinese ad, is their oblivious response to international criticism and lack of response from Chinese consumers, who met the ad with apathy. What other deeply rooted racist tropes still float around in commercials that we consume every day? The next time the commercial break comes on, watch with a critical eye and an engaged mind.

Likewise, fat bodies get read differently depending upon the context in which they are viewed. In the mainstream United States and other western cultures, fat bodies are often labeled unhealthy, lazy, sexually and physically unattractive, and as belonging to a lower socioeconomic status. Fuller- figured women, who are held to a different standard of beauty than their heavyset male counterparts, are often pressured to eat healthy and exercise. Yet finding fashionable and functional exercise clothing in plus sizes is a rather difficult undertaking. Even the name—plus- sized—speaks to their difference and position as other. Larger female bodies are rendered simultaneously visible and invisible. On the one hand, they are resented and shamed for taking up too much space. On the other hand, they are summarily dismissed and largely omitted from media representations, except for when they are being subjected to ridicule. Depictions of fat female bodies in movies often cast them as the witty sidekick, the loveable friend, or the woman desperately in search of a romantic partner, but rarely the leading lady. And even then, she is more often than not cast as a comedic figure who bumbles her way into love.

In Jamaica, Mauritania, Papua New Guinea, South Africa, and Tahiti, fuller, curvier bodies are viewed as a sign of material and financial prosperity, good health, desirability, suitability for marriage, and beauty. The bodies of fuller-figured women are coveted, for they are believed to be well fed and healthy. During the height of the AIDS epidemic in South Africa, fuller figures suggested the individual had a clean bill of health and was HIV-negative. In Samoa, larger bodies are the norm for both men and women, although western influence in more urban areas has resulted in a slimming down of the populace. In the early 2010s, the practice of leblouh experienced a resurgence of popularity in the West African country of Mauritania. Girls as young as five to seven years of age are sent to fat farms where they are forced by women called “fatteners” to consume as many as 16,000 calories a day in order to make themselves attractive to male suitors. The prevailing belief in Mauritania is that a woman’s size is reflective of the amount of space she holds in her husband’s heart. But younger generations of male and female Mauritanians are pushing back against the practice, which is often championed by older women who are fearful their daughters will be unable to secure a good and stable marriage and suffer as a result.

Behind the Virtual Velvet Rope

by Sarah Baum

In the 1970s heyday of nightclubs like Studio 54, it was common to line up and wait to be selected to enter the exclusive venue. How you looked, what you wore, and who you were determined whether you gained entry. This was expected, but in the 2020s world of social media, we’ve moved beyond such superficial examinations. Or have we?

A 2019 document came to light dictating what was and was not acceptable on the social media platform TikTok. It turns out the standards were even more restrictive than back in the 1970s. Anyone deemed to have an “abnormal body shape, ugly facial looks, dwarfism, obvious beer belly, too many wrinkles, eye disorders,” a disability, or other “low quality” traits were censored away from the global stream of sharing. Even if the user was found to be acceptable by physical appearance, they still might be disqualified for having a poor environment, literally. In addition to physical beauty, TikTok censors limited access to anyone whose environment appeared “shabby, dilapidated,” or “poor.” The reasoning TikTok gives for this draconian censorship is as an attempt to “prevent bullying,” but their internal documents do not list this as an issue. Rather, they blatantly confirm it’s for their own public image in an attempt to attract and retain their idea of the right kind of user.

When we use social media, it’s easy to overlook the ropes that section off the companies’ perceived undesirables, but with the global reach of these platforms, our only real voice is in the choice to patronize these companies or not. How do you feel about TikTok’s policy of excluding diversity and inclusion? Will their censorship of economic disadvantage and physical difference influence your desire to use their platform? What can you do to encourage equality and justice in the social media sphere?

The fact is that our bodies are imbued with meaning from almost the moment of conception. One question often posed to expectant parents is, “Do you know what you are having?” This question speaks to the importance of knowing the fetus’s sex so that we might determine an “appropriate” means of understanding and treating the unborn child based upon whether they will be a boy or a girl. The body the child will inhabit determines all manner of things, from the theme and décor of their nursery, the color of their clothes, the toys they will play with, to the name they will bear.

The proliferation of gender-reveal parties in English-speaking countries underscores the emphasis on the body. Videos posted to social media sites depict friends and families gathering to celebrate the child’s impending birth, sometimes to cringe-worthy effect, with would-be parents or siblings expressing their disappointment upon learning the fetus’s sex is not that for which they had hoped. These celebrations usually play upon stereotypical notions of gender, replete with blue-for-a-boy and pink-for-a-girl decorations. Social media influencer Jenna Karvunidis is credited with starting the trend in 2008.

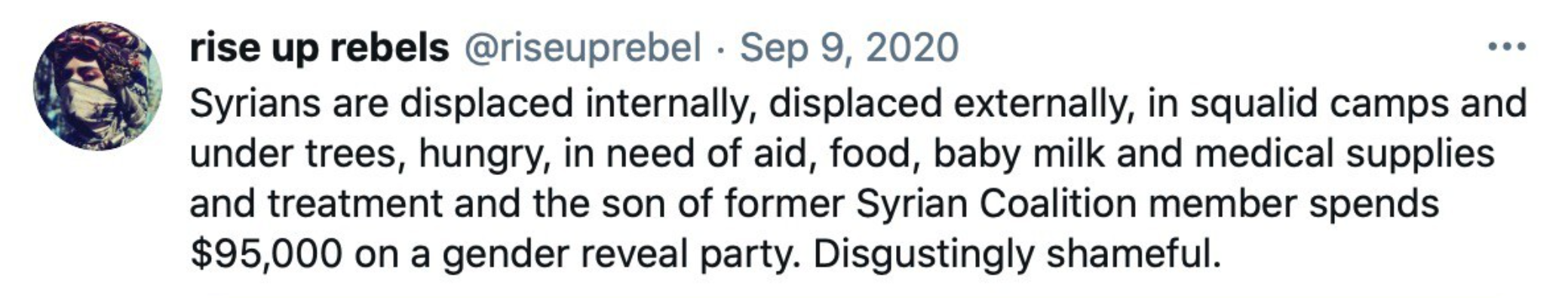

In 2020, following a party that sparked a massive wildfire in California that burned more than seven thousand acres of land, gender-reveal events came under fire. On the heels of the California party, a Syrian couple in the United Arab Emirates, Anas and Asala Marwah, hosted what has been dubbed the world’s biggest gender-reveal party. Broadcast on Instagram and viewed 1.7 million times, the Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world, was lit with blue lights and is believed to have cost more than $100,000. On social media, the celebration was panned for its lavishness and insensitivity. Twitter user @riseuprebel tweeted, “Syrians are displaced internally, displaced externally, in squalid camps and under trees, hungry, in need of aid, food, baby milk and medical supplies and treatment and the son of a former Syrian Coalition member spends $95,000 on a gender reveal party. Disgustingly shameful” (2020).

Interestingly, Karvunidis reversed her position on gender-reveal parties in 2019: “‘I know it’s been harmful to some individuals. It’s 2019, we don’t need to get our joy by giving others pain,’ she says. ‘I think there’s a new way to have these parties.’ ‘Celebrate the baby,’ she says. ‘There’s no way to have a cake to cut into it, to see if they’re going to like chess. Let’s just have cake’” (Garcia-Navarro 2019).

Just as advances in technology aided the popularization of gender-reveal parties, they have also provided expectant parents with the ability to discern the sex of the fetus before birth and delivery. As a country, China has a patrilineal family system, whereby sons are preferred over daughters because the family line descends through the former. Under the country’s one-child policy, which dictated that married couples could have only one child, many families were forced to take drastic measures to ensure the birth of a male heir. The advent of small, portable ultrasound machines enabled expectant parents in China to determine the sex of the fetus, allowing them to terminate pregnancies that might bear female children. In 2015, China ended the thirty-five-year-old policy. On the one hand, the policy helped to curb China’s rapid population growth and improved the quality of life for women and children in general as well as people living in rural areas. On the other hand, the policy resulted in host of societal issues, such as forced abortions, the confiscation of children by government officials, an impending shortage of workers, and “a population that’s basically too old and too male and, down the line, maybe too few” (Gross 2016). More importantly, the policy resulted in 30 million (presumably heterosexual) bachelors (known as guang guan, or “broken branches”) who cannot find women to marry, some of whom are now turning to human trafficking as a means of finding wives. An unintended consequence of China’s one-child policy is that urban women born after 1980 have been afforded the opportunity to obtain an education and build professional careers.

China’s one-child policy underscores the fact that bodies that are marked as different, as being outside of what is considered the norm, are vulnerable to violence. Even babies and children are not safe from violence being enacted upon their young bodies. Take, for instance, the medical interventions performed on intersex babies and children or girls in the Global South and immigrant communities. Amnesty International estimates that “1.7% of children in the world are born every year with variations of sex characteristics.” As a result, these children do not fit “neatly” into either a male or female body. In order to make their bodies conform to the male/female binary, many of these children are forced to undergo surgery: “in Germany and Denmark, where Amnesty International recently conducted research, many people born with variations in sex characteristics undergo surgery during infancy and early childhood to ‘normalise’ their gender appearance, despite being too young to consent to such medical interventions.” Parents, fearful their child “will face psychological problems or harassment in the future,” are put in the position of having to make long-term decisions in the best interest of their child without full and adequate information. Many of these surgeries are thought to be medically unnecessary. Not only do these procedures deprive intersex children of their right to determine their own gender and force them into an outdated male/female binary, they also “have long-term consequences on their right to health and their sexual and reproductive rights, particularly since they can severely impede people’s fertility.” Amnesty International warns that “these interventions may violate human rights, including the rights of the child, the right to physical and bodily integrity and the right to the highest attainable standard of health” (Amnesty International, n.d.).

Similarly, in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, as well as within diaspora communities around the world, girls, often before the age of 5, are forced to undergo female genital cutting (FGC) or female genital mutilation (FGM). FGC refers to the practice of surgically removing all or parts of a girls’ external genitalia because of long-held communal beliefs born out of a desire to control women’s bodies and their sexuality. To learn more about FGC, refer to chapter 4 in this volume, “Sexualities Worldwide.” Ultimately, the parents of children who undergo FGC believe they are doing what is in their daughter’s best interest—ensuring her marriageability, fertility, and safety. While medical interventions on intersex people in the United States and other western countries are framed as “corrective” and nonviolent, FGC is frequently viewed as “barbaric” and has been deemed an international human rights violation, although in both instances, medically unnecessary procedures are performed upon individuals without their consent.

The treatment of children, whether it be through the gendered socialization of their bodies, the use of unnecessary medical interventions for intersex children, the female genital cutting of girls in the Global South and immigrant communities, or the infanticide of girl children in China, underscores the assertion that “as children lack voices in public politics, the body is at the core of how [they] experience, negotiate, and communicate politics in their lives” (Cele and van der Burgt 2016). Like adults, especially members of minoritized and marginalized groups, children learn to understand and mediate body politics in a world that is not designed for them. Their very bodies, which are small in stature in comparison to most adult bodies, identify them as children. Most public spaces are intended for normative cisgender male bodies (think subway straps that are just out of reach), abled bodies (think curbs, stairs, and places without disabled access), and average-sized bodies (think narrow seats without much leg room on airplanes). Far too often, “the childish body is perceived as ‘unruly’ and in need of control in public spaces” (Colls and Hörschelmann 2009). Ultimately, children become aware of their otherness and learn to behave in ways that are acceptable through their actions, clothing, and manner of speaking: “as children have no, or very limited, voice in society, the main tool they have to meet and resist exclusion, segregation, and injustice is the way they perform and present their physical body when meeting others” (Cele and van der Burgt 2016).

As we age, our bodies and the ways in which they are read and interpreted change. The onset of menses is a significant period in many cisgender young women’s lives, signaling a transition from a girl to a woman in many cultures. The young woman’s ability to bear and sustain children is viewed as both a blessing and a curse. In some instances, menstruation is shrouded in mystery and is a source of embarrassment: “the UK can be particularly guilty of this, with people often getting awkward around the very topic of periods. At best, we calmly hand a sanitary towel or a box of organic cotton tampons to a girl who has started her period, give her a brief anatomical ‘birds and the bees’ speech and call it a day—she probably doesn’t want a fuss to be made after all” (Artsculture 2019) Fortunately, not every culture responds in the same manner.

BuzzFeed asked its readers to share their experiences with menstruation in their culture. Many of the responses they received were about the respondents’ first period. Below are seven stories describing their community’s response in “21 First Period Traditions from Around the World” (Armitage 2017):

You have a party thrown to celebrate your transition into womanhood where you don’t leave the house for three days, then get presents and a huge party (typically). You mustn’t be around children or men during your first period.

—Nyiko, South Africa

My mom rinsed my underwear (literally just with water) and smeared it all over my face because she said it would prevent pimples in the future. She made me jump three steps from the stairs because it signifies how many days you’ll be on your period.

—Shane, 23, Philippines

When I got my first period I was at my grandparents’ summer house. I called my grandma over to the toilet, told her what I saw on my panties, and when she saw the blood she SLAPPED ME. She literally slapped me. I had already been scared by blood and dried stains, and now I was terrorized.

I thought I had done something wrong. I got very ashamed. Then she started to laugh and said that it is a conventional thing. She told me that young girls who got their first period should be slapped right there so that their cheeks will always seem red, and also they will have a sense of shame throughout their lives. I think the latter one is the actual reason though.

—Damla, Turkey

You need to lick a teaspoon of honey to make the future periods easier.

—Peleg, 17, Israel

I don’t know if it happens in other countries, but here in Brazil, when a girl has her first period, every member of the family and the family’s closer friends needs to know about it. It’s like a ritual for celebrating.

—Stéfani, 21, Brazil

When you have your first period everyone starts to call you “signorina,” which means “miss” or “young lady,” and your relatives make sure that anybody who knows you gets informed about the good news. So it can become kind of awkward when your parents’ old friends all congratulate you in the strangest ways.

—Maria, 16, Italy

Older family members tend to let you have a glass of red wine when you’re having your first period.

—Lucija, 20, Croatia

I was in Walmart when it happened and my dad asked if he should buy me a cake.

—Mandy, 28, United States

The stories BuzzFeed published revealed the onset of menses is commemorated by celebrations with family, friends, and community members, tradition, ritual, superstition, old wives’ tales, a sense of mortification, a growing sense of reverence and respect, food, beverages, and, most importantly, lots of cake.

But as cisgender women’s bodies mature and begin perimenopause before transitioning into menopause, the perception of women’s bodies, their status and power, also undergoes a change. In the United States, there is a prevailing belief that with menopause comes the end of a woman’s physical attractiveness and sexual desirability. This manner of thinking lends credence to the erroneous belief that a woman’s body exists solely for the function of bearing children and satisfying men’s sexual desires. It ultimately suggests that a woman’s body is most powerful when it is fertile, a claim supported by R. A. Morton, J. R. Stone, and R. S. Singh in their 2013 article “Mate Choice and the Origin of Menopause.” The authors contend their research demonstrates “how male mating preference for younger females could lead to the accumulation of mutations deleterious to female fertility and thus provide a menopausal period” (Morton, Stone, and Singh 2013, 1). The trio’s research sought to debunk American evolutionary biologist George Williams’s “grandmother hypothesis,” which posits that women enter into menopause to ensure “their children grew up to have grandchildren” (Saini 2014). “Our model demonstrates for the first time that neither an assumption of pre-existing diminished fertility in older women nor a requirement of benefits derived from older, non-reproducing women assisting younger women in rearing children is necessary to explain the origin of menopause” (Morton, Stone, and Singh 2013, 2). Scholar Kristen Hawkes, who has built upon Williams’s grandmother hypothesis through her research on the Hazda people in Tanzania, found that older women are a vital and necessary part of the community, thus explaining how women have evolved to live long beyond their childbearing years: “There they were right in front of us. These old ladies who were just dynamos” (Saini 2014). According to scholar Rebecca Sears, the differing theories about the cause of menopause arise from gender bias that shapes the researcher’s frame of reference: “a lot of menopause work is done by women . . . [and] a lot of work on sexual selection by men is done by men” (Saini 2014). In short, women researchers are inclined to approach the subject as a means of examining women’s usefulness, whereas male researchers focus on women’s lack of sexual desirability.

Aging women also tend to be underrepresented in media representations and popular culture and are in many ways rendered invisible despite the many contributions they make to family, community, industry, and society. “The Dinner,” the third episode in the first season of Netflix’s series Grace and Frankie, starring Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, dramatizes how older women are often ignored and overlooked. Fonda and Tomlin’s titular characters, two divorcees in their eighties whose husbands left them to be together, go to a store to purchase cigarettes. They stand at the counter, where they are blatantly ignored by the young male cashier who turns instead to wait upon a young female customer. After Frankie warns, “I’m about to lose my shit!” in response to being ignored, Grace has the meltdown and admonishes the cashier, “Do you not see me? Do I not exist? Do you think it’s alright to ignore us just because she has gray hair and I don’t look like her?” Frankie leads Grace out of the store. Grace apologizes for her behavior but explains that she refuses to be irrelevant, to which Frankie responds, while pulling a pack of stolen cigarettes from her purse, “I learned something. We’ve got a superpower. You can’t see me; you can’t stop me.” Grace’s revelation speaks to the myriad ways women play upon existing gender stereotypes as acts of subversion.

The problem of being judged based solely upon one’s sex and the supposed limitations of one’s body is not limited to just those women whose bodies fall outside of the norm. In terms of choosing an academic major and ultimately a career, women are more likely to enter care- and service-oriented fields. A study published in 2015 found that the dearth of representation of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields “revealed that some fields are believed to require attributes such as brilliance and genius, whereas other fields are believed to require more empathy or hard work. In fields where people thought that raw talent was required, academic departments had lower percentages of women” (Leslie et al. 2015, 262). Most of the ten lowest-paid jobs in the United States are female dominated, with child care workers, hosts and hostesses, and maids and housekeepers being the lowest paid (Thomson 2016).

The global COVID-19 pandemic has exposed lingering gender inequities and revealed the precarious state of progress made on this front. In “The Shadow Pandemic: How the Covid- 19 Crisis Is Exacerbating Gender Inequality,” Morse and Anderson contend there are two pandemics—the one we hear about on the news and the one that’s largely affecting women:

this shadow pandemic can be seen in a spike in domestic violence as girls and women are sheltering in-place with their abusers; the loss of employment for women who hold the majority of insecure, informal and lower-paying jobs; the risk shouldered by the world’s nurses, who are predominately women; and the rapid increase in unpaid care work that girls and women mostly provide already. The current emergency is poised to deeply exacerbate a stubborn one; while early reports suggest that men are most likely to succumb to COVID-19, the social and economic toll will be paid, disproportionately, by the world’s girls and women. (Morse and Anderson 2020)

Issues of occupational segregation by gender in the field of health care make women particularly vulnerable in the age of COVID. According to Morse and Anderson (2020), “globally, women make up 70 percent of healthcare workers, and in hot spots such as China’s Hubei Province and the United States, they make up 90 percent and 78 percent respectively. Women also do most of the support jobs at health facilities, including the cleaning, laundry, and food service. Thus, they are more likely to be exposed to the virus.” For one, superadded to the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) is the fact that “masks and other equipment designed and produced using the ‘default man’ size often leave women more at risk.” For another, although women make up 70 percent of health workers globally, men occupy 73 percent of the executive positions in global health. In short, “men make the decisions. Women do the work” (Morse and Anderson 2020). Because women lack a place at the table when decisions are made that can have a large impact on their lives, their voices are absent, and their needs go largely unheard. Women need to be represented in leadership positions and included in policy-making decisions.

Inasmuch as body politics are about interpreting bodies, it is also about controlling them. Women’s bodies often function as battleground sites upon which men wage war. Sometimes, as in the case of actual warfare, women’s bodies are used to send messages of male domination and conquest to other men. In the conflict between the Bosnian Muslims and the Serbs, for example,

[Serbs] forced fathers to castrate their sons or molest their daughters; they humiliated and raped (often impregnating) young women. Theirs [Serbs] was a deliberate policy of destruction and degradation: destruction so this avowed enemy race [Bosnian Muslims] would have no homes to which to return; degradation so the former inhabitants would not stand tall—and thus would not dare again stand—in Serb-held territory. (Power 2002, 251)

Girls’ and women’s bodies are also sites upon which battles are waged supposedly in their honor. The supposed need to protect girls and women are at the heart of the debate about the transgender bathroom usage and immigration policies in the United States. In 2016, when Target announced that it would allow transgender team members and guests to use the restrooms and dressing rooms that corresponded to their gender identity, the decision was met with calls from conservative groups for a boycott. After a man exposed himself in front of a young girl at a Target store in 2018, evangelist Franklin Graham took to Twitter to call, once again, for a boycott of the store. While Graham claims to be acting in defense of women, he conveniently overlooks the precarious and often dangerous situation that transgender women and girls, whose bodies are policed by violence because they are thought to deviate from normative ideas about heterosexuality and femininity, must navigate in performing an act as basic and necessary as going to the bathroom. Graham’s outrage over Target’s transgender bathroom policy is also a red herring that intentionally and disingenuously conflates transgender women and girls with pedophiles and sexual predators (Weinberg 2021).

Documenting Gender Dysphoria

by Rebecca Lambert

Gender dysphoria is a serious issue affecting many transgender people across the world. The American Psychiatric Association defines gender dysphoria as “psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity.”

As a way to raise awareness around the challenges that the trans community faces and help others through similar experiences, the Korean American nonbinary photographer Salgu Wissmath created a photo series titled “Documenting Dysphoria.” The series combines interviews with photography to share the lived experiences of people dealing with gender dysphoria. The photos represented specific moments in people’s lives or general feelings associated with the experience of gender dysphoria. Wissmath notes that the project is not just about gender dysphoria but also gender euphoria, and focuses “on the feelings and experiences that have allowed people to understand their own identity.”

Wissmath centered the trans community in this project and created a visual representation that is meant to support and empower trans people in their own lives. To find out more about the project, visit salguwissmath.com.

Much of the debate around immigration and immigration reform is rooted in rhetoric that focuses on the need to protect women and girls from harm. In a speech announcing his plan to run for president, Trump raised the specter of the immigrant rapist: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people” (Ross 2016).

In order to discourage would-be asylum seekers from entering the country during the Trump administration, undocumented families were forcibly separated at the border, the children detained in cages, teenage migrants who were pregnant as a result of rape were being denied access to abortion services, and the women were coerced into undergoing sterilization procedures (Manian 2020).

Women’s reproductive health and rights remain one of the most contested battleground sites. Around the globe, abortion rights are under attack with legislative efforts to restrict, outlaw, and criminalize abortion activities. In the United States, the death of US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg highlighted the precariousness of Roe vs. Wade and the legal protections it has afforded women in need of abortion care. In January 2021, Poland enacted a near-total ban on abortion. Even before the most recent law,

Poland already had one of Europe’s most restrictive abortion laws with the procedure legal in only three instances: fetal abnormalities, pregnancies resulting from rape or incest, and threats to a woman’s life. The latter two remain legal. But with 1,074 of 1,100 abortions performed in the country last year because of fetal abnormalities, the ban would outlaw abortion in most cases and critics say many women will resort to illegal procedures or travel abroad to obtain abortions. (Kwai, Pronczuk, and Magdziarz 2021)

The Hazards of Innovating: Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Constitutions Worldwide

by Shannon Garvin

In September 2020, US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died and left a gaping hole not only in the US Supreme Court, but also in the ranks of legal champions of human rights for all individuals. As a young lawyer, Ginsburg argued a number of high-profile cases, carefully chosen to create a web of judicial precedence on which lawyers could argue and judges could rule in favor of women, minorities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) people, even though none of these groups have protected rights in the US Constitution. Eventually, RBG (as she would come to be known) was nominated to the Supreme Court, where she championed human rights until her death.

In 2004, RBG was present in South Africa at the inauguration of their constitution after the end of apartheid (a system of race segregation). In 2006, after the “Arab Spring” uprising, she was in Egypt and noted to the press that as Egypt was writing a new constitution, she would recommend looking to the South African constitution.

Backlash ensued. The following day she released a written speech on her full thoughts on the matter, noting that while US justices cannot look to external laws when forming court decisions, today the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights and newer constitutions like South Africa’s exist and flourish, ensuring human rights not guaranteed in our founding documents. RBG understood this dilemma we now face. The world has learned from us and improved on our pioneering beliefs, but how do we take the next steps to build on these in our current times?

In response to news of the Polish government’s decision, proponents of the bill took to the streets to protest even though the country was experiencing a surge of new coronavirus cases. The protests in Poland are being hailed as transformative; “some are calling it the ‘cardboard revolution’ in reference to the handmade placards that have become a distinctive feature of the protests” (Muszel and Piotrowski 2020).

Your Body Is a Battleground Poster Resurfaces in Poland

by Shannon Garvin

Symbols hold power. Barbara Kruger’s Your Body Is a Battleground poster, first created to defend Roe v. Wade at the 1989 Women’s March in Washington, DC, has become the visual symbol of demonstrations in Poland.

Poland has some of the strictest abortion laws in Europe. Most Poles support less restrictive abortion laws, but the Catholic Church backs the conservative government and stricter controls over women’s health care. In October 2020 the Constitutional Court, backed by the Catholic Church, ruled that the 1993 law allowing abortion for severe and irreversible fetal abnormalities (98 percent of abortions in 2019) is unconstitutional.

Kruger recently told Artnet News in an email, “It is both tragic and predictable that the brutal conditions that led to my producing this image so many decades ago are still at work controlling women’s bodies and their access to reproductive care. The structures of power and containment are relentless in their choreographies of marginalization and exclusion.” Asked why she is continuing to print posters in cooperation with TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art to defend the rights of women, Kruger replied, “the urgent and brave protesting of marginalized, disempowered and newly empowered bodies is an insistent threat to the dominant and extremist choreographies of religion, power, and politics in Poland. The brazen hypocrisy of the Church and its predictable fist-bumping with the political right make for a grotesque dance of male bonding and resolute abuse of power.”

Every day, girls and women engage in subversive and outright acts of activism, resistance, and rebellion as they fight to gain autonomy over their lives and bodies. They do this by breaking into male-dominated fields, thereby shattering glass ceilings. In January 2021, Kamala Harris made history on a number of fronts, becoming the first woman, first Black woman, and first Asian American vice president of the United States. The United States is also currently experiencing an increase in the number of people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) elected to public office: “particularly pronounced increases were seen in the number of LGBTQI+ majors, with a 35 percent year-over-year jump; the number of bisexual and queer-identified people, with increases of 53 percent and 71 percent, respectively; and the number of transgender women serving in elected office, with a 40 percent year-over-year rise” (Fitzsimmons 2020).

“Naked Athena” Exposes Her Body and Political Power

by Shannon Garvin

Portland, Oregon, became the center point of Black Lives Matter protestors and police and federal officials during its nightly demonstrations in 2020. Protesting itself holds a rich history in this quirky urban area. On July 18, 2020, at 1:45 a.m. during another night of stand-off between protestors and federal officers sent by the Trump Administration to “protect” federal buildings, an unidentified woman dressed only in a face mask and cap calmly walked to the center of the street, where rubber bullets and tear gas were flying. She sat, made ballet moves, and struck yoga poses. For ten minutes, police continued to shoot at the protestors behind her, and she side-stepped a man who attempted to shield her. Eventually, she wandered home anonymously around 2:00 a.m., unharmed.

Nakedness has long been considered an acceptable form of protest in Portland. In a place where everyone was wearing chemical filtering masks and using umbrellas to fend off bullets and spray, however, her nakedness was a shocking display of vulnerability. In summer 2020, as an Oregonian, I stayed up late each night to watch the bravery, stamina, and occasional stupidity of protestors who caught the ire of an oppressive presidential administration. In a world where men and religion compulsively seek to control female bodies, the use of a naked body by a woman in political protest unhinged men and exposed their lack of understanding and their fear. Body politics are powerful voices.

Girls and women also use their bodies to shatter stereotypical and outdated notions of beauty. The rise of body positive and fat influencers on social media sites such as Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok showing larger female bodies living and loving life, wearing fashionable clothes, and simply taking up space pushes back against the notion that fat bodies are shameful and need to be hidden away.

Feminist Protest Performance in Chile

by Rebecca Lambert

Las Tesis Collective is a Chilean feminist group that uses art to resist violence against women and challenge oppressive state structures. The group gained popularity in 2019 when their song “Un Violador en Tu Camino” (“A Rapist in Your Path”) gained international attention. Las Tesis called for feminists around the world to gather and protest violence against women, resulting in crowds of women across the globe coming together to sing the song. The song is a feminist anthem that challenges the violence of the patriarchy, including rape, slut-shaming, and victim-blaming.

Members of the collective include Lea Cáceres, Paula Cometa, Sibila Sotomayor, and Daffne Valdés; they performed their song in public for the first time in November 2019 at Chile’s Supreme Court building. In May 2020, Las Tesis collaborated with Pussy Riot, a Russian feminist protest performance group, to release a song highlighting the increase in domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic (Front Line Defenders). The national police filed a lawsuit against the collective accusing them of inciting violence, but the case was dismissed in January 2021.

In Chile, where “gender-based violence has reached epidemic proportions” (McGowan 2020), women lead the resistance efforts. The song “A Rapist in Your Path” (Colectivo Registro Callejero 2019), which has become an emblem of the movement in Chile as well as Colombia, France, Mexico, Spain, and the United Kingdom, “depicts a world in which state oppression mirrors sexual violence, and singles out police, judges and the president as accomplice in the aggression” (McGowan 2020). In 2016, a photographer captured an image of Ieshia Evans, a nurse from Pennsylvania who traveled to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to protest the extralegal killing of Alton Sterling and Philando Castille at the hands of police. The iconic photo depicts Evans, clad in nothing more than a flowy summer dress and flats, being rushed by officers in full riot gear. During the summer of 2020, women around the world joined Black Lives Matter protests in response to the killings of Americans George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbury. In Portland, Oregon, a group of women called Moms United for Black Lives (formerly Wall of Moms) stood in solidarity in front of Black Lives Matter protestors, shielding them from tear gas and the use of excessive force by police offices. Girls and women literally put their bodies on the line in the fight for gender equality, social justice, and political change. Their activism and resistance bring to mind the conclusion of Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?”: “if the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them” (Sojourner Truth Memorial Committee, n.d.).

Learning Activities

- Butts discusses the case of Frances Gage, who “fictionalized the text and the incidents the day” on which Sojourner Truth gave her famous speech. In Gage’s version of the speech, Truth says, “Ain’t I a woman?” But in the version of the speech that scholars consider to be the most accurate, Truth says, “I am a woman’s rights.” Using the terms and concepts from this chapter, consider the differences between the question, “Ain’t I a woman?” and the statement, “I am a woman’s rights.” Which seems more rhetorically powerful? Why? Why might Gage, a white woman, prefer her fictionalized version? Take a look at the website TheSojournerTruthProject.com, which includes videos of Afro-Dutch women reading Truth’s speech in order to demonstrate to viewers what Truth might have sounded like. What do you learn about the speech when listening to it performed by Afro-Dutch speakers?

- Butts discusses at length the ways that bodies are gendered and socialized as male or female, even before babies are born. What examples does she provide? Can you provide additional examples?

- What are the implications of menstruation and menopause on women’s lives? Can you think of cultural representations of menstruation and menopause? What are they? What do they communicate about menstruating and/or postmenopausal women?

- Butts discusses the ways that body politics are about controlling bodies. What examples does she provide? What examples can you add?

- How are queer and trans bodies and voices represented in this discussion of body politics? Use the information you learned in this chapter to build on the discussion of queer and trans bodies from the previous chapter

- Working in a small group, add these key terms to your glossary: body politics, body rules.

References

Amnesty International. n.d. “First, Do No Harm: Ensuring the Rights of Children Born Intersex.” Accessed February 15, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2017/05/intersex-rights/.

Armitage, Susie. “21 First Period Traditions from Around the World.” BuzzFeed. June 3, 2017. https://www.buzzfeed.com/susiearmitage/21-first-period-traditions-from-around-the-world.

Artsculture. 2019. “How Do Different Countries Celebrate Periods?” Accessed February 18, 2021. https://artsculture.newsandmediarepublic.org/health/how-do-different-countries-celebrate-periods/.

Butler, Bethonie. 2014. “Yes, Those Kim Kardashian Photos Are about Race.” Washington Post. November 21, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/she-the-people/wp/2014/11/21/yes-those-kim-kardashian-photos-are-about-race/.

Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge.

Cele, Sofía, and Danielle van der Burgt. 2016. “Children’s Embodied Politics of Exclusion and Belonging in Public Space.” In Politics, Citizenship and Rights, edited by Kirsi Kallio and Sarah Mills, 1-14. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4585-94-1_4-1.

Cisneros, Sandra. 1991. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Contemporaries.

Colectivo Registro Callejero. 2019. “A Rapist in Your Path.” YouTube video, November 26, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aB7r6hdo3W4.

Colls, Rachel, and Kathrin Hörschelmann. 2009. “The Geographies of Children’s and Young People’s Bodies. Children’s Geographies 7, no. 1, 1-6.

Davis, Kathy. 2002. “Feminist Body/Politics as World Traveller: Translating Our Bodies, Ourselves.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 9, no. 3, 223-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506802009003373.

Fitzsimons, Tim. 2020. “LGBTQ Political Representation Jumped 21 Percent in Past Year, Data Shows.” NBC News. July 16, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/lgbtq- political-representation-jumped-21-percent-past-year-data-shows-n1234045.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books.

Garcia-Navarro, Lulu. 2019. “Woman Who Popularized Gender-Reveal Parties Says Her Views on Gender Have Changed.” NPR. July 28, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/07/28/745990073/woman-who-popularized-gender-reveal- parties-says-her-views-on-gender-have-change.

Grace and Frankie. 2015. Season 1, episode 3, “The Dinner.” Produced by Netflix. May 8, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=80GfMMVL3rw.

Gross, Terry. 2016. “How China’s One-Child Policy Led to Forced Abortions, 30 Million Bachelors.” NPR. February 1, 2016. https://www.npr.org/2016/02/01/465124337/how-chinas-one-child- policy-led-to-forced-abortions-30-million-bachelors.

Hull, Akasha (Gloria T.), Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith, eds. 2015. All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies, 2nd ed. New York: Feminist Press at CUNY.

Kwai, Isabella, Monika Pronczuk, and Anatol Magdziarz. 2021. “Near-Total Abortion Ban Takes Effect in Poland and Thousands Protest.” New York Times. January 27, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/27/world/europe/poland-abortion-law.html.

Leslie, Sarah-Jane, Andrei Cimpian, Meredith Meyer, and Edward Freeland. 2015. “Expectations of Brilliance Underlie Gender Distributions across Academic Disciplines.” Science 347, no. 6219, 262-65. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261375.

Manian, Maya. 2020. “Immigration Detention and Coerced Sterilization: History Tragically Repeats Itself.” American Civil Liberties Union. September 29, 2020. https://www.aclu.org/news/immigrants- rights/immigration-detention-and-coerced-sterilization-history-tragically-repeats-itself/.

McGowan, Charis. 2020. “‘Our Role Is Central’: More Than 1m Chilean Women to March in Huge Protest.” The Guardian. March 6, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/06/chile-womens-day-protest.

Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds. 2015 This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, 2nd ed. New York: Kitchen Table / Women of Color Press.

Morse, Michelle, and Grace Anderson. 2020. “The Shadow Pandemic: How the COVID-19 Crisis Is Exacerbating Gender Inequality.” United Nations Foundation. April 14, 2020. https://unfoundation.org/blog/post/shadow-pandemic-how-covid19-crisis-exacerbating- gender-inequality/.

Morton, Richard A., Jonathan R. Stone, and Rama S. Singh. 2013. “Mate Choice and the Origin of Menopause.” PLOS Computational Biology 9, no. 6, 1- 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003092.

Muszel, Magdalena, and Grzegorz Piotrowski. 2020. “‘They’re Uncompromising: How the Young Transformed Poland’s Abortion Protests.” OpenDemocracy. December 11, 2020. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/theyre-uncompromising-how-the-young-transformed-polands-abortion-protests/.

Otis, Eileen. 2016 “China’s Beauty Proletariat: The Body Politics of Hegemony in a Walmart Cosmetics Department.” positions 24, no. 1, 155-77. https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-3320089.

Our Bodies, Ourselves. n.d. “Our Story.” Accessed February 13, 2021. https://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/our-story/.

Power, Samantha. 2002. A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. New York: Basic Books.

@riseuprebel. 2020. “Syrians are displaced internally, displaced externally, in squalid camps and under trees, hungry, in need of aid, food, baby milk and medical supplies and treatment,” Twitter. September 9, 2020. https://twitter.com/riseuprebel/status/1303835052095176705.

Ross, Janell. 2016. “From Mexican Rapists to Bad Hombres, the Trump Campaign in Two Moments.” Washington Post. October 20, 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the- fix/wp/2016/10/20/from-mexican-rapists-to-bad-hombres-the-trump-campaign-in-two- moments/.

Saini, Angela. 2014. “Menopause: Nature’s Way of Saying Older Women Aren’t Sexually Attractive?” The Guardian. March 29, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/mar/30/menopause-natures-way-older- women-sexually-attractive.

Shaw, Carolyn Martin. 2021. “Body Politics.” Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, updated February 24, 2021. https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/body-politics.

Sojourner Truth Memorial Committee. n.d. “Sojourner’s Words and Music.” Accessed February 19, 2021. https://sojournertruthmemorial.org/sojourner-truth/her-words/.

Stenberg, Amandla (@amandlastenberg). 2015. “@novemberskyys when you appropriate black features and culture and fail to use ur position of power to help black Americans by directing attention towards ur wigs instead.” Instagram. July 13, 2015.

Thomson, Stéphanie. 2016. “The Simple Reason for the Gender Pay Gap: Work Done by Women Is Still Valued Less.” World Economic Forum. April 12, 2016. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/04/the-simple-reason-for-the-gender-pay-gap- work-done-by-women-is-still-valued-less/.

Waylen, Georgina, Karen Celis, Johanna Kantola, and S. Laurel Weldon, eds. 2013. “Body Politics.” In The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics 1-3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199751457.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199751457.

Weinberg, Abigail. 2021. “The Real Threat to Women’s Sports Isn’t Trans Athletes. It’s Sexually Predatory Coaches.” Mother Jones. February 26, 2021. https://www.motherjones.com/mojo-wire/2021/02/the-real-threat-to-womens-sports-isnt-trans-athletes-its-sexually-predatory-coaches/.

Image Attributions

3.1 “Body Positive” by nme421 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2 .0

3.2 Photo by Billie on Unsplash

3.3 Instagram post by seventeen.com, © theshaderoom

3.4 Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

3.5 Twitter post by Rise Up Rebels, Sept 20, 2020, 4:17 PM

3.6 Photo by Monika Kozub on Unsplash

3.7 Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash