Women’s Work in a Global Ecomony

Paula Sheridan

Exploring women’s work in a global economy is an ongoing challenge and delight. The statistics and narratives vary depending on who, what, and how you ask. But the overall picture is generally the same: women in our global economy have more difficulty than men in getting a job and earning equitable wages.

We acknowledge women’s intersecting identities and roles: women of different ages, sexual orientations and identities, geographic locations, social classes, political and spiritual beliefs, physical abilities, immigration status, and women with and without children. Mainstream literature and research inadequately represent the many identities of working women in a global economy. Many databases provide binary information, making it difficult to understand the experiences of women with diverse identities. Therefore we learn how to use the data we have and create new ways of asking questions that represent all women and their experiences, giving voice to those who are silenced or made invisible by multiple oppressions.

What challenges do working women encounter? Some of these barriers include the power of patriarchy, unequal wages, educational inequality, and unequal access to opportunities. A Thomson Reuters Foundation poll identified work-life balance and the gender pay gap as the top two of five major concerns of the women participants. Do you see any connections that shape your ability to succeed in the workplace?

Banking Deserts and Gender Inequality

by Shannon Garvin

Banking deserts are areas of the world where people have little to no access to basic banking services. The World Bank’s Global Findex report finds that “more than half of adults in the world’s poorest areas still have no access to the financial system.”

Technology is making banking more accessible in some parts of the world, but it is not narrowing the gender gap. In Southeast Asia, only 37 percent of women have bank accounts, versus 65 percent of men. Sub-Saharan Africa has seen a boom in account ownership with the easier access to smartphones in the past few years. This has raised account ownership from 51 percent to 62 percent globally. World Bank Group president Jim Yong Kim said, “Access to financial services can serve as a bridge out of poverty.”

But we might consider that there are numerous additional factors women face when banking in their countries, including exclusion from legal rights to own accounts, male guardianship or permission required, not having access to money of their own, or, having so little money it is kept in cash.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is backing a US initiative to offer basic banking services at local post offices to protect people from the outrageous fees offered at check-cashing storefronts. In an increasingly global, digitized economy, without access to digital funds, it is harder to accomplish basic financial transactions.

How do the challenges that working women face relate to their daily consumptions of food, clothing, lifestyle? The products and services we consume are global commodities and connected to a gendered workforce. Many of these items are produced in women’s homes, neighborhoods, or workplaces. If we want to understand the global commodity chain, we need to comprehend the role that gender plays on the global level (Cravey 2015, 15).

Working Women in a Global Economy: Perspectives

We discuss several theoretical lenses and perspectives in this chapter. But two overarching perspectives help us organize and understand women’s work in a global economy. The ecological perspective allows us to see many connected systems that shape women’s work and the types of relationships between systems that enhance or deter human thriving. The empowerment perspective helps us look at these systems, analyze the power relationships, and develop strategies that build more life-enhancing systems.

An Ecological Perspective

The ecological or ecosystems perspective views individuals as complex systems that shape and are shaped by physical and social environments, allowing us to see the connections between and within an individual, group, community, and global interactions. Building on human ecology, we see humans and their physical and social environments as being interconnected. This perspective also identifies the type of interactions between people, social, and physical environments that can enhance or deter the quality of life for all (Brown and Mills 2001, 16). We can group systems according to size: microsystems (individuals and families), mezzosystems (communities and organizations), and macrosystems (national and global institutions such as government, health, education, commerce, and others).

Gitterman and Germain (2008) help us think about living spaces or niches and habitats in ecosystems, our social structure in the environment. We develop our niches through attributes attributed to us (gender, race, ethnicity) and those we earn (education, income) (Brown and Mills 2001, 16). Solomon (1976, 13) discusses how niches can injure Black individuals, families, and communities when a niche is not valued or is systemically oppressed through gender, age, and/or ethnicity. Thus the workplace can be a safe or dangerous niche, depending on the resources in the physical and social environments. Habitats, the places where we live and dwell, can also suffer from systemic oppression and power imbalances. The physical layouts of urban and rural community settings, including our workplaces, schools, homes, communities, can damage our sense of self when they are inadequate, unsafe, and fail to provide education and other resources that help us thrive (Brown and Mills 2001, 17).

Solomon (1976) identifies ways that power and resources are blocked from women and other disenfranchised groups by looking at unequal accesses to power and resources in systems (Brown and Mills 2001, 16). This perspective can help us link the many systems and structures of women’s work in a global economy. Systems connected to women’s successful work include such things as the presence of health care, reproductive rights, child care, legal advocacy, and workplace advocacy.

An ecological perspective provides a way to map the systems that affect women’s global work and the quality of the relationships between systems. For example, companies may benefit from women’s labor and production. Still, women can be exploited by companies with unfair wages and unsafe or neglected work environments, making this an imbalanced and unjust interaction. An ecological perspective helps us target strengths and challenges on micro-, mezzo-, and macrosystem levels that women encounter as workers in a global economy.

An Empowerment Perspective

Empowerment is a process and an outcome that occurs on micro-, mezzo-, and macrosystem levels. With roots in feminist theory and community organization methods, empowerment theory and practice increase “personal, interpersonal, or political power so that individuals can take action to improve their life situation” (Gutiérrez 1990, 149). An empowerment perspective or approach addresses barriers to problem-solving imposed on stigmatized groups by an external or dominant society (Solomon 1976, 21). Empowerment perspectives, used in advocacy work to support the disenfranchised and counteract feelings of powerlessness created by unfavorable valuations of stigmatized group, identify the direct and indirect power blocks that contribute to the problem, and develop an action response to reduce or eliminate resistance (Solomon 1976, 19).

We can confuse empowerment as saving, rescuing, or depriving others of their own decision-making and action. In this context, however, empowerment means developing power, seizing power from oppressive places. Empowerment lies in the person and structure.

Janet Townsend et al. (2000) learned about transforming forms of power as they listened to women in Tapalehui, Mexico. These women, living in a poor, rural area, shared their approaches to advocacy and change with Townsend, who identified four forms of power. The women of Tapalehui described power that oppressed their growth and change, which Townsend defined as power over. When women shared their hopes and struggles with other women, they experienced power from within. When women joined together to address their concerns, they experienced power with. Women expressed a power to do when they made concrete changes that improved their lives, such as earning wages and completing projects (Finn 2001, 275; 2016, 36). Such broader understandings of power originate from the life experiences of these poor, rural women in Mexico.

Afghan Women Leading the Way

by Renea Perry

The women of Afghanistan are leading the way for each other and for the future of their country. In September 2020, Afghan Deputy Speaker of the Parliament Fawza Koofi was one of four women delegates (of twenty-one delegates total) selected to attend peace talks with the Taliban in Qatar. In her negotiations, she sought to have the Taliban respect Afghan women’s rights to education, to work, and to travel freely as well as the things that are important for the country to thrive. Women’s right to be a visible part of Afghan society is gaining traction. “I’m not asking a charity from them. It’s my right,” she says.

An all-women’s soccer team was formed in 2007. The league shut down in 2017 because of a lack of funding, but it was reinstated by the Afghan government in 2018 after allegations of rape and physical abuse by the Afghan Soccer Federation president were reported by women players and he was banned from the sport for life. The players who came forward about the abuses, and those who continue to play despite threats from the Taliban and the dislike of some community members, have dreams of playing for the national team.

As time goes on, women in Afghanistan are also gaining family support for attending school and working. In early 2021, an all-female Afghan flight crew for a private airline flew a Boeing 737 from Kabul to Herat with two women pilots and four women cabin crew members. This is the first such flight in the country’s history. Pilot Mohadese Mirzaee explained that her mother suggested she go to flight school, telling her, “everything is possible.”

Addendum: Since the above was written, massive changes have taken place in Afghanistan. The United States withdrew its military forces, and the Taliban immediately moved in and took over the country. In spite of reassurances from the US government, the rights of women and girls have not been protected under this new oppressive regime.

Take action: Start with the link above, and do some research into current conditions for women and girls in Afghanistan. Choose one small action—send an email, make a donation, host a fundraising event, educate others. If you can, do more to support the women and children struggling to recover some of the freedoms they have lost.

Influenced by Paulo Freire’s belief in critical reflection and critical awareness, the empowerment perspective analyzes power and how people and systems distribute power in society. Power and empowerment come from individuals and groups and are not bestowed from a more dominant group (Finn 2016, 158). We don’t empower other people. We support others in empowering themselves. Empowerment approaches develop consciousness-raising and capacity building in ways that challenge oppressive structures and conditions, working simultaneously toward personal agency and social change.

Like the ecosystems perspective, an empowerment perspective makes connections between and among the multiple systems in our lives. This lens identifies systems that affect women who work in a global economy, analyzes power relationships that support or deter women, and removes the blocks of unmet needs on multiple system levels. In summary, ecological and empowerment perspectives and frameworks inform how we understand and respond to the challenges and opportunities of working women in a global economy.

Working Women in a Global Economy: Challenges

We are the oil in the wheels.

It is our work in households which enables others to go out and be economically active….

It is us who take care of your precious children and your sick and elderly; we cook your food to keep you healthy and we look after your property when you are away.

—Vicky Kanyoka, Tanzanian Trade Unionist, 2010 (Boris 2019)

The ecosystems perspective allows us to identify and critique the many systems that shape women and are shaped by women in a global economy. The empowerment perspective and approach give us strategies and skills to evaluate and implement needed changes in our lives and the systems that women in a global economy encounter. In this section, we look at the systemic challenges that women who work in a global economy face.

Gender Gaps in Labor Force Participation Rates

Someone who is employed or actively looking for work is a participant in the labor force. The global labor force has an unequal percentage of women and men. The International Labour Organization (ILO) was founded in 1919 as a nongovernmental organization designed to establish global labor standards. For many years, women’s inequality was not a focus for the organization, but now the ILO addresses women’s inequality in the workplace and labor unions, unsafe working conditions, and efforts to improve women’s lives (Faue 2018, 509). In March 2018 the ILO reported that 49 percent of women were employed, compared to 75 percent of men. What does this mean? The ILO suggests that women have more difficulty finding a job than men and are more likely to be employed in vulnerable jobs with fewer work hours, unpaid work, lack of maternity coverage, and less job security.

Women spend about three times as many hours as men in domestic and care work, and women with young children at home do even more. Additional stressors reduce women’s participation in the workforce by 75 percent. During challenging times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, however, women and men take more responsibility for home duties and child care. Still, women and girls assume most of the duties, returning to the prepandemic pattern.

ILO and Gallup global surveys of women suggest that 70 percent of women prefer to work in paid jobs. Some women, depending on where they live, experience unwanted moves and resettlement, high levels of poverty and unemployment, and cultural/family codes that discourage women from formal education, employment, and mobility without male supervision. Traveling to work can be dangerous. The ILO provides a series of InfoStories to help us understand both the big picture of global data and the personal narratives that are worthy of our attention.

Gender Wage Gaps in the US and the Global Economies

Wage gaps are differences in wages between groups of people, particularly the earning disparities between women and men. Generally, organizations measure wage gaps in hourly rather than annual wages to more accurately compare the earnings of women and men who do the same amount of work.

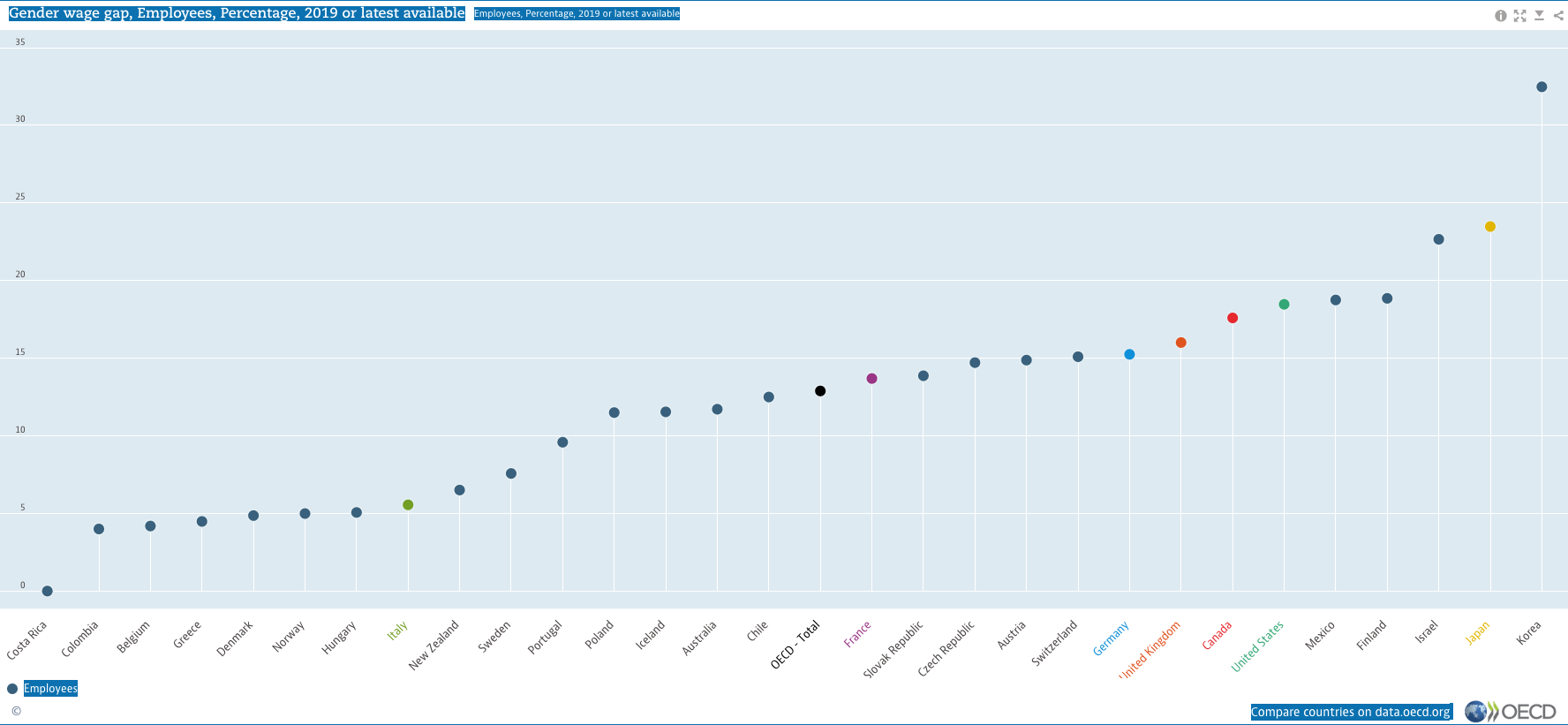

The Organisation of Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) is an international organization that includes policy makers, governments, and citizens to develop policies for better lives. Some of the initiatives include economic, social, and environmental changes. The ILO focuses on a different measure of the gender wage gap, the median earnings of men compared to women’s median earnings in full-time employment from 2015 to 2019. The wage gaps range from lower disparities (Costa Rica, 4.0 percent; Denmark, 4.9 percent; Italy, 5.6 percent; Chile 12.5 percent) to larger disparities (United States, 18.5 percent; Israel, 22.7 percent; Japan, 23.5 percent; and Korea, 32.5 percent). The following chart shows the wage gaps in OECD countries. Even with multiple measures, most data show that women still earn lower wages than men in the global labor market.

In the United States, women’s wages have increased but still are less than those of men. In an analysis of wages from 1979 to 2016, Nunn and Mumford (2017, 19-22) report that US women have made significant progress in education, salary increases, and workforce participation; as women’s wages have increased, men’s wages have fallen. The unadjusted wage gap accounts for the wage differences between women and men caused by discrimination, occupation, and other factors. It is larger than the adjusted wage gap, which shows the differences in wages after accounting for the observable factors. Both the unadjusted and adjusted wage gaps have declined between women and men (Nunn and Mumford 2017, 23).

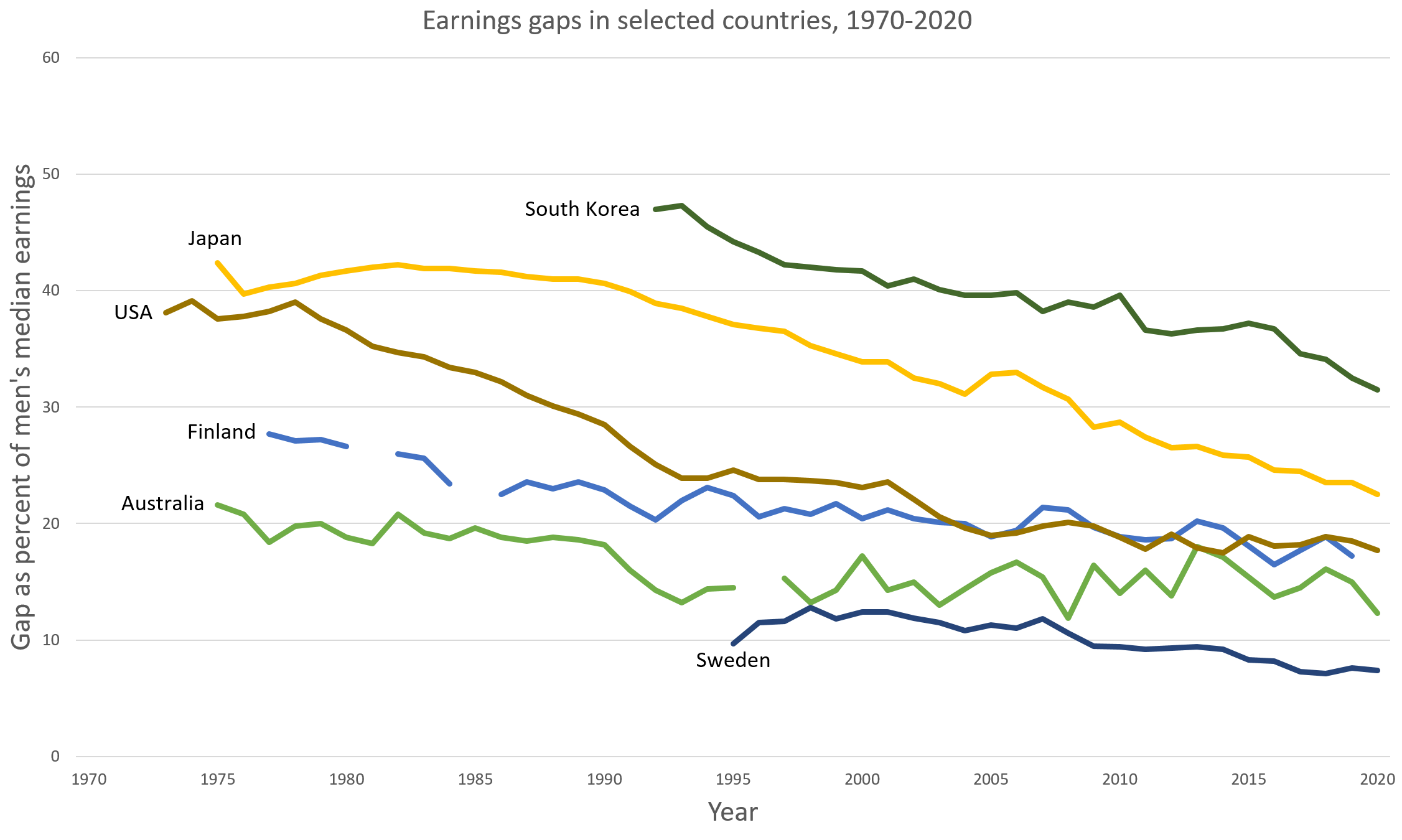

When we compare US wage gaps to other industrialized countries, the US wage gap in unadjusted earnings among women and men was higher than in comparable countries but is now more in the middle range. The OECD compiles earnings data from national agencies to compare the differences in unadjusted wage gaps from full-time employed men and women. Countries with higher wage gaps, such as South Korea and Japan, have slight reductions in their wage gaps. Countries that began with smaller wage gaps, such as Australia, Finland, and Sweden, are still narrowing the wage gaps, as illustrated in the following chart.

These gains occur with continued occupational segregation, the degree to which women or men fill an occupation such as nursing, social work, and education. Other factors that sustain the gender wage gap include wage discrimination and challenges in balancing work and family responsibilities that women experience (Nunn and Mumford 2017, 28-29).

Decreased Participation in the US Labor Force

From 1960 to 2000, up to 78 percent of prime-age women (ages 25-54) in the United States who vary in age, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, and with and without children were in the labor force, with numbers increasing over time. The growth of women in the labor force contributed to family income and US economic growth. Since 2000, however, the percentage of prime-age women of the same profile decreased by 3.5 percent in the labor force. Not all participating OECD countries reflect this trend. Canada, France, Japan, and the United Kingdom show a rise of prime-age women in the labor force.

Her Standpoint: Julia, a US Social Worker and Life Coach

interview by Paula Sheridan

Julia Hartman combines her skills in medical social work with a private coaching practice, bringing comfort and support to individuals and families with a variety of needs. To learn more about her professional care work, her thoughts on how women can navigate a flawed system and support each other, and her strategies for self-reflection, empowerment, and growth, follow the link here. (Passcode: k#DpJL#7)

Compared to those of other developed countries, the US labor force receives fewer unemployment benefits, has no paid maternity leave, and has fewer policies that support family integration and work in women’s lives (Black, Schanzenbach, and Breitwieser 2017, 19). In comparison, Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden) and Finland have welfare systems, called the Nordic model, financed by taxes that support citizens throughout the life cycle. The Nordic model includes early childhood education and day care, extensive family leave policies, equality for persons who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+), extended work holidays, strong labor unions who support worker salaries and benefits, retirement pensions, health care, and other services. Danish citizens bear the highest tax burden (49.5 percent), but wages are high. These resources are available for all citizens and many noncitizens. The Nordic model is most successful when a large percentage of the population is employed and paying taxes.

The Laws of Jante

by Lily Sendroff

The Laws of Jante, or Janteloven, is a cultural concept that dictates social code in Nordic societies (the countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden). Janteloven is not a literal law enforced in the region, but a general moral code that emphasizes the greater good over the individual. The term was first coined by Danish Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose in his 1933 novel A Fugitive Crosses His Tracks. Janteloven is ingrained into Nordic people from a young age, and it shows up culturally in a tendency to champion collective accomplishments and disdain individual triumphs.

In his novel, Sandemose lays out ten written laws that encapsulate the relationship between the collective and the individual in Nordic culture. The general message: Do not think you are smarter than anyone, better than anyone, more important than anyone, or can teach anybody anything they do not already know.

The impact of Janteloven is apparent in Nordic welfare states, where high taxes are endured for robust social services. In places like the Nordic countries—where collective well-being is prioritized—aspects of socialism are able to gain more public support than in places like the United States, where health care is privatized, welfare programs are comparatively weaker, and there is a cultural emphasis on the individual. Another major contributor to the success of socialized welfare and Janteloven is the ethnic homogeneity of the region, which political economists find to be correlated with support for public programs.

Despite strong welfare states, Nordic countries are still capitalist. In fact, many blame the modesty and discouragement of competition upheld by Janteloven for hindering economic growth in Nordic countries on the global scale. Especially among younger generations, the Laws of Jante have been losing both relevance and influence socially and culturally.

There are more downsides to be seen in the extreme modesty encouraged by Janteloven. While the Nordic region is a global pillar for gender equality, their economic model results in gender segregation by occupation. Janteloven’s emphasis on modesty in professional settings can ultimately discourage women from speaking out, which masks and sustains structural gender discrimination, including a gender-based pay gap, in these countries.

Whether the critique of Janteloven comes from those who believe it is time to do away with modesty for economic growth or those who see its imperfect application, the relevance of Jante has been called into question. Its influence, however, remains undeniably present.

In Her Voice: Katrine, a Working Mother in Denmark

interview by Paula Sheridan

Katrine is a teacher working in an early childhood setting, as well as a mother to an infant daughter.

She explains the Danish system, which varies in significant ways from, for example, the system in the United States. Pros for her include guaranteed parental leave; cons include a gender-based pay gap.

Listen to the story in her voice.

Gender Segregation in the Workforce

The global labor force includes many segregations or segments (age, region, class, race, ethnicity, immigration status, sexual orientation, and identity). Some segregations are bound by gender (lower wages, “women’s work,” maternity leave). Women who experience an intersection of gender and other segregations in the labor force are affected more intensely.

Domestic labor is a primary factor in the gender segmentation in the labor force in many cultures. Women with lower incomes and women in developing countries are overrepresented in paid and unpaid domestic labor. Practices include child-rearing, the primary responsibility for home management, and other unsalaried but essential care tasks. This domestic model has been replicated in the marketplace and supported by social values, norms, and, in some countries, laws. Other influencing factors that segment women from equal wages include legal policies, trade unions that do not challenge local practices such as lower wages for women, formal and informal organizational policies and practices, and lower job negotiations for and by women (Peetz 2019, 213-21).

Sexual Harassment

Only six countries legally mandate equal rights at work: Belgium, Denmark, France, Latvia, Luxembourg, and Sweden, according to the World Bank. In these countries, laws protect men and women against sexual harassment, provide equal pay, and offer family leave. Even countries such as Denmark and Sweden, known for a heritage of feminist movements and women in government leadership, have recently addressed women’s claims of harassment in the workplace. These two national economies receive the highest ratings from a World Bank index that examined laws related to women’s economic empowerment in different phases of their working lives (World Bank 2019, 2), but significant numbers of women in each country challenged sexual harassment at work.

In 2019, a Danish-Swedish university study compared each country’s response to the #MeToo movements. The study found that Swedish news reports described the “systematic, structural, gender-related violence” of politicians and citizens in different ways. Danish media focused on witch hunts and excessive political correctness. But both countries enacted legislation that now offers more protections to women. In Sweden, explicit consent is the standard for sexual interactions, with the onus on criminal defendants to prove that their victims granted consent. Amnesty International initially criticized Denmark for vague and confusing wording about consent laws. In 2019, new Danish legislation created more specific protection for consent, stating that “sex without consent isn’t sex” (Rosenblad 2020).

France also has a mixed picture of gender equality, with the highest percentage of women in the workforce in Europe and accessible day care, but a gender pay gap of 15.2 percent less earnings than men in 2016 and heightened claims of sexual harassment and assault related to the French #MeToo movement, known as #BalanceTonPorc, or “out your pig.” The government has a gender equality minister and legislation to punish “harassment in the streets” with fines of €750 ($840). Critics note that older citizens are more likely to tolerate excuses of male harassment that are unacceptable to younger men and women (Beardsley 2019).

A Thomson Reuters poll of ninety-five hundred working women in developed countries listed harassment as the third workplace concern, following work-family balance and equal pay. Approximately 29 percent of participants interviewed experienced sexual harassment, but more than 60 percent did not report it. Indian women were the most likely to speak out (53 percent).

Unprotected Class in Workplace Discrimination: Challenge and Hope

LGBTQI+ rights are human rights and economic issues. In addition to the personal costs of social stigma and exclusion, the economy loses access to talents and abilities that enhance a global workforce. LGBTQI+ harassment in the workplace also diminishes the capacity of LGBTQI+ workers. Studies in Canada of LGB (not including transgender people) and India of LGBTQI+ exclusion suggest that employment discrimination and health disparities yield losses of billions of dollars to their economies (Badgett, Park, and Flores 2018, 4). Everyone loses.

Conversely, when LGBTQI+ people can develop and use their skills in the economy, more talent is accessible for economic development. The research findings of Badgett, Park, and Flores (2018, 10–11) suggest that LGBTQI+ inclusion increases economic performance as measured by the gross domestic product. Countries that include and support LGBTQI+ people may be more likely to have stronger economies. When countries enhance the health and welfare of LGBTQI+ persons and remove stigma and barriers, the economy and LGBTQI+ persons are more likely to achieve a higher potential (Badgett, Park, and Flores 2018, 11).

In the United States, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits workplace discrimination on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, and national origin. Later, Congress extended workplace protection on the basis of age (1967), disability (1990), and some veteran statuses (1974). People who belong to these groups are members of a protected class. The United States made some progress in LGBTQI+ rights with the US Supreme Court decision affirming marriage equality (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015) and President Obama’s executive orders that prevented LGBTQI+ discrimination for federal contractors and established equality laws in cities and states. In 2020, the US Supreme Court decision in Bostock v. Clayton County ruled that LGBTQI+ discrimination is a type of sex discrimination and therefore illegal under the Civil Rights Act.

Equal under the Law?

by Shannon Garvin

The Constitution of the United States was groundbreaking when it was written, guaranteeing rights never so clearly afforded to citizens. But the framers could not foresee the ways in which their work would change the world and how the homogeneity of the men present did not represent the whole of humanity.

Since 1781, Congress and the states have continued to revise and expand the meanings of the original words. As culture has changed to recognize the full humanity of people with all shades of skin and all genders, we must continue to work to afford full legal status and human rights to all people.

While the Equal Rights Amendment was passed in 1972, its ratification still has not been officially recognized as part of the constitution. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 clearly outlined the civil rights of people of color who, while freed from slavery, continue to struggle for equal treatment under the law and in practice. Likewise, today, H.R.-5, known as the Equality Act, which prohibits discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity, continues to come before Congress, intending to expand and ensure the full legal status of persons of all static and gender-fluid identities. The work for equality for all presses on.

During his first day in office on January 20, 2021, President Joseph R. Biden signed an Executive Order on Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation (White House 2021). This order builds on the Bostock decision, which protects those who identify as LGBTQI+ from employment discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Alphonso David, president of the Human Rights Campaign, called it “the most substantive, wide-ranging executive order concerning sexual orientation and gender identity ever issued by a United States president.” Biden reversed discriminatory policies from the previous Trump administration that would allow sports teams and bathrooms to be exempt from the effects of the Bostock decision.

While this executive order is liberating, the United States still has no national law that extends protected-class status to LGBTQI+ persons in the workplace. Only federal employees have been protected by antidiscrimination policies that include sexual identity since 1998 and gender expression since 2012. Congress repeatedly failed to pass national legislation that would include sexual orientation and gender identity expression as a protected class since it was first introduced in 1994.

On February 18, 2021, however, Representative David Cicilline (D-RI), an openly gay congressman, reintroduced the Equality Act, which he has proposed since 2015. The bill would amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other federal legislation to protect the LGBTQI+ community from discrimination in key areas of life, included housing, credit, employment, education, and public spaces and services. This bill builds on the Bostock ruling and civil rights legislation over the past forty years.

While we advocate for federal legislation establishing LGBTQI+ persons as a protected class in the workplace, some companies have voluntarily adopted nondiscrimination policies for LGBTQI+ persons, including formal LGBTQI+ employee resource groups that advocate for inclusive policies and practices, Safe Zone trainings (Safe Zone Training, n.d.) to diffuse anti-LGBTQI+ bias, and fair resource distribution (Cech and Rothwell 2020, 56; Steiger and Henry 2020, 27).

The ecological perspective allows us to see the structures of injustices that transgender people face in multiple systems throughout their life spans: as children in their homes, in schools, in social settings, in the doctor’s office, with police officers, and judges. Each one of these barriers is related to one’s right to work. The National LGBTQ Task Force and the National Center for Transgender Equality (2011) report that 6,450 transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals completed a survey about the far-reaching injustices in their lives. The feedback of participants from fifty US states and territories provide data that enable policy makers, activists, and legal advocates to address the unsettling and unjust realities. A summary of the metafindings, the big picture, suggests that “the combination of anti-transgender bias and persistent, structural racism” was devasting, particularly for people of color (Grant et al. 2011). African American transgender respondents fared worse than others in most areas examined. The findings report that transgender respondents live in extreme poverty and are “nearly four times more likely to have a household income of less than $10,000 a year than the general population.” Forty-one percent of the respondents reported attempting suicide, compared to 1.6 percent of the general population. Those who lost a job due to bias (55 percent), were bullied/harassed in school (51 percent), or were victims of physical assault (61 percent) or sexual assault (64 percent) reflected higher rates of suicide attempts.

Working while Trans

by Ramona Flores

In the United States, no company or organization is legally allowed to deny a transgender employee a raise or promotion based on their gender identity, with the same being true about termination. The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission bluntly outlines, “discrimination against an individual because of gender identity, including transgender status, or because of sexual orientation is discrimination because of sex in violation of Title VII.”

Many states, including California, Colorado, Iowa, Maine, and New Mexico, have explicit state laws prohibiting discrimination based on gender identity or expression. Similarly, section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act prohibits sex discrimination but doesn’t outline explicit protections for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) people.

The decision in Franciscan Alliance, Inc. v. Burwell, however, combined prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of gender identity for the nation. While this was seen as a small victory, in 2020 the prohibitions were fully eliminated, allowing for gender identity-based discrimination in health care and insurance. Bolstered by the US Supreme Court case Bostock v. Clayton County, both homosexual and transgender employees reserve the right not to face any professional backlash because of their sexuality or gender identity and therefore have the precedent to pursue legal action if they do experience discrimination.

Transgender people also have to worry about whether their company will recognize their partners/spouses for maternity or paternity leave, whether their company’s dress code will allow them to dress according to their identity, and whether their company will support them if they report a hostile work environment or discriminatory language.

The National Center for Transgender Equality in the United States reports that “more than one in four transgender people have lost a job due to bias and more than three-fourths have experienced some form of workplace discrimination” (Grant et al. 2011). This could include refusal to hire, workplace discrimination, privacy violations, harassment, and physical or sexual violence. Transgender people of color report even higher numbers. While recent US legal rulings such as Bostock v. Clayton County ensure more equity and inclusion, trans women still seek safety and normalcy when using the bathroom, wearing clothes that are consistent with their gender expression, and being addressed in a respectful manner. Jane Fae, a transgender activist, notes that “changing your forename and gender at work remains troublesome for many, despite its relative ease in the eyes of the law” (Jenkin 2012). Fae suggests that employers and employees should have clarity on issues surrounding transition and being transgender as well as provide a safe space for people to discuss their anxieties and fears. This includes a work culture that is inclusive and intolerant of discrimination. The results of this study are limited to the United States and US territories, so we do not assume these findings are the same in other countries.

Disabilities and Disablism

It is normal to experience a disability during our life cycle, though we may see disability as far removed from our own experiences. Disabilities, which vary widely and can include one’s vision, hearing, movement, mental health, thinking, ability to communicate, and more, can be visible or unseen by others.

We view disabilities through various lenses, particularly the social and medical models. The social model, developed by people with disabilities, advocates that societal barriers and attitudes disable people, such as buildings without accessible toilets, stairs, and assumptions that people with disabilities cannot do what others can do. The social model helps us acknowledge that human-constructed barriers make life more difficult. The medical model assumes that people are impaired or different, focusing on deficiencies rather than human potential. Such a model could lead to the loss of human agency, creating dependence and loss of choice and opportunity for people with disabilities.

Disablism is a term that describes discrimination or prejudice against people who have disabilities. Disablism manifests in a person’s attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors. We see structural forms of disablism when people with disabilities are excluded from participation because of the social biases in training, hiring, promotions and in the physical design of buildings that deny access (stairs instead of ramps or elevators, inaccessible bathrooms).

People with disabilities represent at least 15 percent of the world’s population. According to ILO (2015b), there are more than 1 billion people with disabilities in our world, and at least 785 million are of working age. A UN Women report on women and girls with disabilities (UN Women, n.d.) identifies that one in five women lives with a disability, and these women are among the most vulnerable populations. They are diverse in intersectional identities such as ethnicity, religion, citizenship status, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, marital status, and health. Approximately 36 million women in the United States have disabilities, with 44 percent of individuals 65 or older living with a disability. In the United States, 26 percent of adults, more than 61 million people, have a disability. One in four is a woman. These numbers are higher in Indigenous communities, such as non-Hispanic American Indians or Alaskan Natives.

The ecosystems perspective (Brown and Mills 2001, 16) helps us understand that women’s geographic, economic, and social positions can shape one’s inaccessibility to resources. For example, in the United States, women with disabilities are less likely to receive regular health screenings for breast cancer and cervical cancer. Women and girls who reside in countries at war, with internal political conflict, poverty, and natural disasters are even more likely to be invisible, marginalized, or harmed. Human Rights Campaign (2012) has documented barriers to education and violence to children in schools. Sex- and gender-based discrimination and other abuses highlight the vulnerability of people with disabilities, particularly women and girls, who have more limited access to health care, education, employment, and civic involvement. Even though a woman’s right to make personal reproductive choices is protected in numerous human rights treaties, disabled women are subjected to forced or coerced sterilization in some parts of the world.

The empowerment perspective (Finn 2016, 158) shapes our critique of life-affirming actions for people with disabilities. Disability inclusion is a commitment to include people with disabilities in roles like their peers. Many inclusion strategies reflect principles and strategies of the empowerment perspective, involving people with disabilities in developing inclusive policies and practices in the workplace, creating, and utilizing knowledge and statistics that shape innovative inclusion.

Social protection is a form of disability inclusion founded in the human rights framework that facilitates moving beyond traditional welfare approaches to interventions that promote “active citizenship, social inclusion, and community participation while avoiding paternalism and dependence” (Social Protection-Human Rights, n.d.). The 2006 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) informs social protection, specifically Article 28, recognizes the right to adequate living standards and social protection without discrimination based on ability. These provisions, ranging from housing, education, training, medical care, would persist throughout the life cycle.

One example of social protection for employed women with disabilities is the work of the Trade Union Congress (2021), the national center for trade unions in Britain representing more than 5 million workers and forty-eight member organizations. Their 2016 report researched the intersectional discrimination of disabled women in member unions and provided intervention strategies that include women with disabilities. Disabled women have a 32.5 percent higher gap of unemployment than nondisabled women and are paid 36 percent less than nondisabled men. In 2015, the report Still Just a Bit of Banter? explored the experiences of more than a thousand disabled women. Approximately 68 percent reported sexual harassment at work, compared to 52 percent of women in general. Employed women with disabilities reported multiple harassments (54 percent) and described lasting effects on mental health, physical well-being, and security in the workplace. Two-thirds of the women did not report harassment to their employer, believing it would either not be taken seriously or harm their careers.

The ILO provides two approaches for disability inclusion: both mainstream services and activities (skills training, employment promotion, social protection, poverty reduction) and disability-specific programs that address particular barriers or disadvantages. The ILO recommends additional actions for disability inclusion: providing capacity-building opportunities such as the inclusion of people with disabilities at policy and planning on local, national, and global levels; linking disability issues to national development and poverty reduction efforts (youth employment; offering more opportunities for women and girls, rural development); and improving work opportunities in rural and informal economies (International Labour Office, 2015a).

Paid and Unpaid Care Work

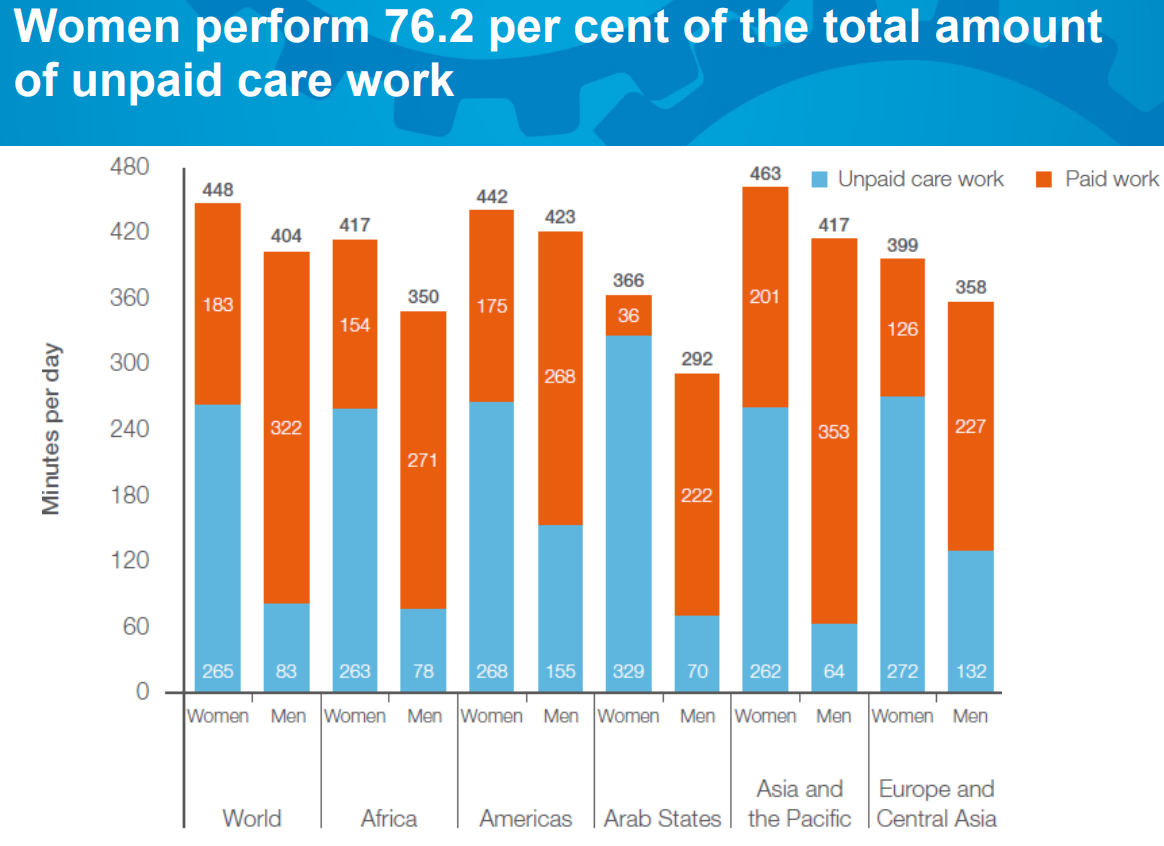

How do we determine whether an occupation is defined as caring labor? One way is to notice the emotional demands on workers. Are workers expected to invest emotional labor, care work, to others in their jobs? Child care workers, nurses, teachers, social workers, and elder care workers, which are predominantly women, fall in this category. The International Labour Organization categorizes care work as paid and unpaid. Unpaid care work is provided without monetary reward and was determined by the ILO to be work (ILO 2018a, 29). Women perform more than 76 percent of unpaid care work in the world. Women care workers are more likely to have less paid work hours, more obstacles to having high-quality jobs, and work in informal economies with fewer contributions to pensions and employee benefits.

Arlie Hochschild (2000) explored how paid and unpaid labor mirrors and reproduces women’s subordination. She coined the term “global care chain” to describe patterns of women in developing countries in Latin America and Southeast Asia migrating to more developed countries to care for children of affluent families. But who cares for the children the immigrant caregivers left at home? Hochschild links household duties to a larger political economy. The migrating caregiver represents an economy that is neocolonial and unequal in power dynamics (Boris and Fish 2014, 415; Nadasen 2017, 124).

Some feminists have developed and challenged some of Hochschild’s ideas. We cannot assume that all female migrants are mothers, heterosexual, or emotionally care about the children under their responsibility. Manalanson (2008) encourages a queering of migration studies to allow for a broader range of gender identity and the unlinking of biological parenting and care.

Unpaid care work is work that is more invisible. Unpaid care work includes housekeeping, child-rearing, family care, and domestic tasks that support family and community. It may be done as an act of love or survival. Care work is shaped by culture, law, and economic need. Care is associated with women and embeds stereotypes of nurture and tenderness. This embodiment limits women and dismisses the caregiving abilities of others. Caregivers are often women of color and immigrants who have been invisible in the world of white women’s feminism (Peetz 2019, 213-15).

The following chart shows the minutes per day that men and women perform unpaid care work in a global setting.

Ai-jen Poo, director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, advocates for Universal Family Care, a plan that provides domestic workers, the majority of whom are immigrants and women of color, with resources to care for children, elders, and other family members while they are working. This shifts the care work from an individual person to a social network that is supported by law (Poo 2019).

Women Working in a Global Economy: Sustaining Strategies

The world is our picket line.

—Liverpool Dockers (Sagmoen 2020, 325)

Strategies that target gender equity for women in a global workforce are most successful when they are designed and implemented on the micro-, mezzo-, and macrosystem levels in women’s lives. This section examines selected interventions and initiatives from global groups and grassroots organizations.

Global Policies for Gender Equity at Work: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, all United Nations member states adopted an action plan of seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a global partnership to address challenges to world peace and prosperity by 2030 (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2020). The UN created the Division for Sustainable Development Goals to oversee, support, and promote global ownership of the goals and action plans. Examples of individualized SDGs address poverty, hunger, health and well-being, education, gender equality, environmental sustainability, climate action, economic issues, and reduced inequalities.

UN Women, an entity of the United Nations, furthers gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. It supports member states by supporting governments and civil society in planning and implementing policies and programs that benefit women and girls. UN Women (2021) attests that gender equality is essential for attaining these goals and reviews each of the seventeen SDGs with gender-specific indicators.

Because women’s work connects to multiple ecosystems represented in the SDGs, we can identify goals that support a more equitable, sustainable global workforce. When women are safe at home, work, and in their communities; are healthy; and have the agency to make life decisions, they have a more significant opportunity to be successful at work. SDG 5 plans to achieve gender equality and power among women and girls by ending harmful practices such as forced marriage, genital mutilation, violence, and discrimination against women. SDG 5 also supports issues connected to women’s global work: eliminating the gap in value between paid and unpaid women’s work, increasing access to sexual and maternal health and reproductive rights, providing women with equal rights to economic resources and ownership according to national laws, enhancing technologies that promote women’s empowerment, and adopting and strengthening policies and legislation that promote gender equality and empowerment of all women and girls.

The UN Foundation works with global companies in implementing practices to attain the SDGs. Five global companies with more than 585,000 women workers announced in September 2020 new and expanded commitments to improving the health and well-being of women employees. Some of the participating corporations, convened by the UN Foundation, include Del Monte Kenya, the Ethiopian Horticulture Producer Exporters Association, Farida Group, MAS Holdings, and PVH Corp. These corporations will provide workers in Ethiopia, India, Bangladesh, Kenya, Sri Lanka, and other countries with services on health, well-being, contraception, maternal health, noncommunicable diseases, and protection from sexual harassment and gender-based violence. This intervention makes more opportunities possible as women’s participation in the supply chain increases.

The International Labour Conference: Challenges and Supports for Global Women Workers

The International Labour Conference, founded in 1919, consists of governments, employers, and workers of 187 member states to set labor standards, policies, and programs that “promote decent work for all women and men.” While it is not a feminist organization, feminists have used the ILO to address issues of care, violence against women at work, and most importantly, gender inequality. Historically, the ILO wavered between universal standards for all workers and protections for women workers, reflecting regional and legal restrictions on women’s freedoms. Now the focus is the mainstreaming of women in the global workforce. Recently, the ILO factored the role of care work in the equation of equity. Care work is not adequately addressed by nondiscrimination and safe working conditions (Boris 2019, 4-12). Care work, particularly unpaid care work, is more difficult to document and can be invisible when provided in homes or other caregiving settings. It can be invisible to others, leaving the care worker vulnerable to unreasonable demands from the employer, unsuitable working conditions, and inadequate wages. Care work is often sheltered by cultural norms of male dominance and law.

Public and Private Regulations in a Global Economy

The global supply chain shapes worker conditions. The effects range from cheap goods, corporate profits, and worker exploitation, most often found in the Global South. Labor rights and working conditions require ongoing oversight from government and private regulations. It is not enough for corporations or governments to do this independently through laws and funding incentives. Rather, gender equity along the global supply chain is more possible when government and businesses share responsibility and monitor policies and practices in the workplace (Sagmoen 2020, 324).

Expanding Gender Equity in the Workforce

Organizations often focus on antidiscrimination in the entry process of a job, such as employee searches and hiring. Research in academic settings suggests that institutions focus on formal and informal biases and unintended interactions that are more difficult to identify and monitor.

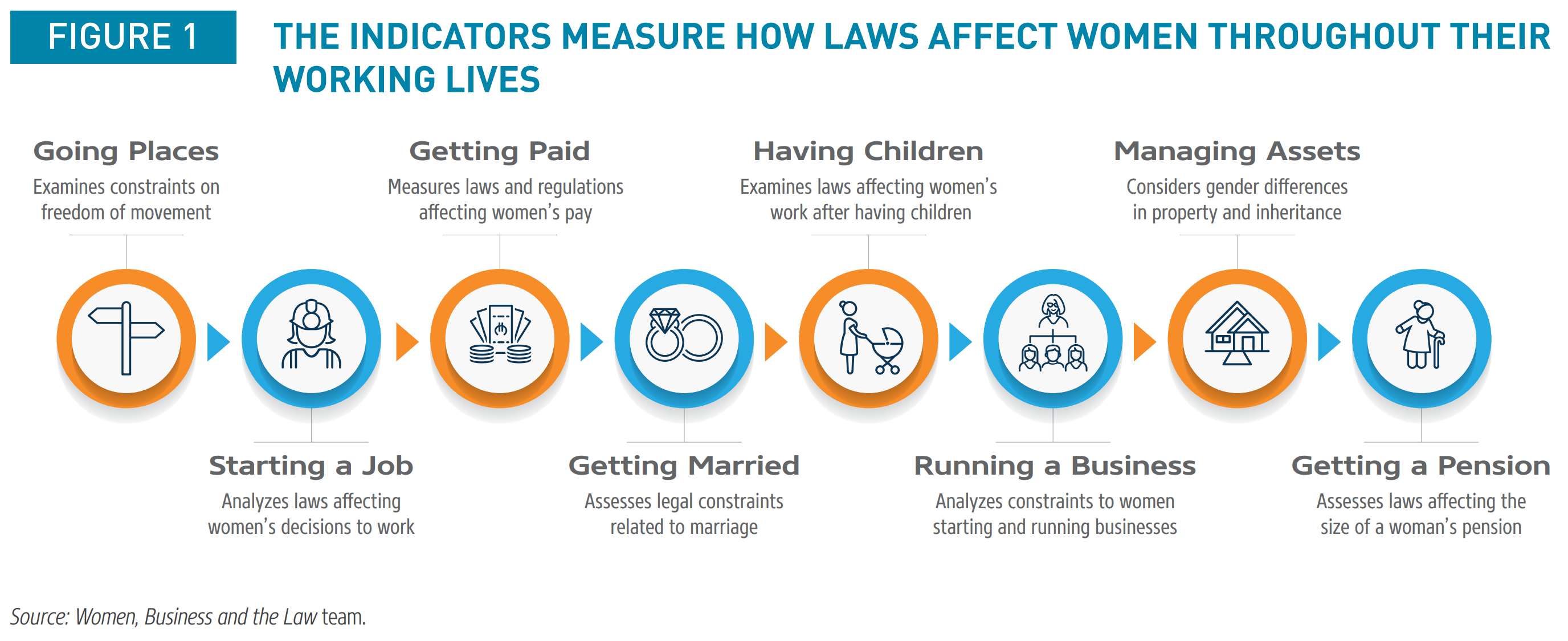

The World Bank (2019) along with external contributors used an index of economic decisions that women make throughout their work cycle to examine how women’s economic decisions are shaped by law. The study collected data on eight indicators that represent preparing to work, entering work, family life, business experiences, and retirement. The findings, published as Women, Business, and the Law: 2019, show that 131 economies have enacted 274 reform laws and regulations, leading to an increase in gender equality over the past decade. Thirty-five economies implemented laws that protect 2 billion more women from sexual harassment in the workplace. Yet the findings indicate that a typical economy gives women only three-quarters of the rights of men in the areas measured.

Gender equity also includes a thriving work environment for people who identify as nonbinary and trans. The American Civil Liberties Union (2021) urged the Biden administration to do more than reverse discriminatory policies from the Trump era. The ACLU advocates the issuing of accurate federal identification for transgender and nonbinary people. The IDs would include two changes: self-declaring of gender markers so that people can confirm their own gender without medical verification, and adding a gender-neutral “X” designation on all federal records and IDs.

The Role of Collective Organizing in Women’s Work

Labor unions are a part of the United States’ political, social, and economic history. In many cases, unions historically shape most workers’ quality of life with wage premiums, health, and retirement benefits. In the past, labor unions were more influential in providing pay rates and benefit packages that set labor market trends. Often, nonunion employers matched the packages to keep union organizing at bay. In 2014, only 6.7 percent of the private sector was unionized (Berg 2015). Until the 1960s, labor unions reflected the cultural norms of countries and organizations rather than challenging them. Since that time, unions have advocated for higher women’s wages, but women are still underrepresented in unions as members and in leadership positions. This trend is recently changing in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, the United Kingdom. Now, women are as likely as men to join unions in similar markets and gain more from unionization. Women in unions are more likely to have a lower pay gap (Peetz 2019, 218-20).

In the United States, unions lost political influence with declining membership and the 2010 ruling by the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. This decision enables corporations and other outside groups to spend unlimited funds on elections, giving greater access to wealthy donors, corporations, and special interest groups.

As membership in labor unions has declined, their political strength to motivate voter activity and advocacy for policies that shape vulnerable workers’ lives has diminished (Berg 2015, 396). As a result, underrepresented union members such as African Americans and immigrants were disproportionately hit.

More recent labor representation models include labor unions, community-based organizations, and worker centers. In New York City, groups of workers who are traditionally unrepresented in unions (street vendors, domestic workers, migrants) organize themselves or collaborate with unions. Such alternative partnerships “improve social justice beyond the workplace” and expand the models nationally (Berg 2015, 396). Students and faculty at City University of New York created a collection of essays of innovative examples of how immigrants, worker centers, labor unions, and others can organize to address the needs of workers within and beyond the workplace and the limits they encounter (Berg 2015, 397).

The global labor force reflects the challenges of local and global economies, reinforcing that work is not only about production and economic growth. For labor to be effective, the needs of vulnerable populations such as women, children, older workers, and people with disabilities should be addressed in the global workplace and market. Workplace safety is also essential to productive labor and product outcomes.

Grow Where You’re Planted

by Sarah Baum

What do you do when your country falls apart around you, and the government that is supposed to help you doesn’t? The easy option is to simply give up and give in to want and poverty, but the women of Haiti refuse to back down. Known as Madan Sara, these rural women run marketplace stalls, selling produce and other necessities. With each sale, they build a life for themselves and their families, creating opportunities for their children out of the efforts of their own creativity and hard work. Madan Sara are the backbone of the Haitian economy and have made themselves economically indispensable.

Even so, they receive no acknowledgment from a hostile government that too often ignores the struggles of these clever and amazing women. Madan Sara have been the glue that’s held the Haitian economy together since almost the beginning of the country, yet these women still have not earned the respect and support they deserve. Every day, they face a lack of infrastructure, social injustice, and highly unstable political settings. Their success alone would be something to be admired, but Madan Sara go beyond merely looking out for their own homes and families. They bind together and help one another against sometimes impossible odds, facing down everything from thefts, threats of rape and physical violence, to debt collectors, and even government-sponsored arson in marketplaces—and they face all of these together, collectively. The power of Madan Sara working together to build a better life is stronger than any adversity they come up against.

It is important to critically analyze attempts to “empower” women in industries that have historically paid low wages and provide unsafe settings. The garment industry in Southeast Asia may appear empowering because women are hired to work in the factories, but they are suppressed by lack of representation, low wages, and unsafe conditions. Women garment workers are self-empowered when they earn decent wages and participate in leadership that determines their best interests in management and unions (Huq 2019, 138).

Ecomaps: A Tool for Mapping Women’s Work and Our Own

by Paula Sheridan

We use the ecosystems and empowerment perspectives to frame our understanding of women in the global workplace. The ecosystems perspective helps us identify the barriers women experience at work and ways that these barriers influence women in their personal, family, work, and community experiences. We also identify resources and organizations that women can use to empower themselves in the global workplace, looking for and creating strengths in many system levels: individual, family, community, workplace, and national and global laws and policies.

We can map these strengths and challenges with a tool, an ecomap, that is used by mental health professionals and organizations to understand a person/persons in the multiple environments they experience. Ecomaps are diagrams that show us the many connections we have to people and systems in our world. We can map information in this chapter and map our own work/life experiences. Use the ecomap link to select an ecomap format that works for you.

Ecomap symbols describe the quality of relationships in the ecomaps. Symbols show us where people find support, conflict, disconnection, ambivalence in our support systems, and more. Symbols can also be used to map health, migration, substance use disorders, losses, and gains in our lives. Here is one of many examples of symbols we use in an ecomap to illustrate relationships between people and systems. Ecomaps belong to the creator. This is a snapshot of how one experiences relationships in life and can change over time. There is no right or wrong, just one’s standpoint.

Create an Ecomap of Women’s Challenges and Supports in the Global Workforce

Create an ecomap that charts the barriers and supports women encounter in the global workforce. Your ecomap can begin with a person in the center. Use the symbols from the above links to show the following structures and relationships that working women may experience:

- Barriers to Success

- In the home

- In the workplace

- From other organizations outside of work (health, education, religion)

- From laws and policies

- Supports That Enhance Success

- In the home

- In the workplace

- From other organizations outside of work (health, education, religion)

- From laws and policies

- Relationships That Provide Support and Challenge

- Many relationships can be ambivalent, both supportive and challenging. Try to map this to show the complex experiences that women face in a global workforce.

Create Your Personal Ecomap of Life and Work

Using the ecomap tools, make an ecomap that represents your experiences with work and the other systems that affect your vocational success (family, school, friends, finances, geographic location, diverse identities, and more). Use the symbols to describe the quality of these relationships. You may see patterns of support, vulnerability, success, or concern. Many times, creating an ecomap can help you clarify your challenges and resources. It can help you see your big picture and the multiple roles in your life. Ecomaps can empower you to be intentional about how you develop your goals, your relationships, and your resources. It can also be something you create over time to see the long view of your life. You may see unexpected connections between your lifestyle and local/global issues that you value.

Conclusion: Knowledge Is Gender Power

In this chapter, we explored perspectives as lenses that help us see the many global systems in the lives of working women. We identified challenges that working women face. We learned about global organizations that target gender equity in the workforce as a human right, not a privilege for some. We see how diverse identity and intersectionality of health, education, sexual orientation, class, and geographic location shape women’s inclusion and exclusion in the workforce.

Who and what did we not address? What women are in the margins, underrepresented in the literature? We need to unearth the stories of women who reside in the Global South—a geographic location and place of limited access to resources—including women who work at home and who identify as nonbinary, and we need to understand how their locations shape their work experiences.

In closing, listen to the stories of women who work in the fashion industry as an example of a gendered global supply chain. These are women who grow cotton for clothes, sew garments in substandard factories or at home, endure exposure to chemicals, and dispose of used clothing in landfills in developing nations. These are the faces of a global supply chain. We see hands and hear the voices of women who prepare products that we purchase online or in a local store. They tell us about the systems that oppress them. They also show us resilience. They invite us to join them by examining the systems that provide us the clothes that fill our closets.

250 Million Children

by Sarah Baum

Who doesn’t love a bargain? Fashion today is ever-changing and disposable. Most of all, it has become cheap, costing the consumer far less than it should because clothing is being made for pennies by sweatshop laborers in developing countries. Women make up 85 to 90 percent of all sweatshop workers, and worldwide over 250 million children—children who should be in schools and dreaming of their futures—labor alongside them. It’s the ugly side of fashion that the consumer never sees.

Sweatshop workers endure abusive conditions and insanely long hours, but the sweatshop isn’t a modern invention. In 1934, Tillie Olsen wrote a poem, “I Want You Women Up North to Know,” about sweatshop conditions in Texas. Little has changed since her poem was published, except the sweatshop workers are now farther away and even easier to overlook.

What can you do about sweatshop labor and conditions?

- Contact your favorite brands and let them know you won’t be spending your money with them if they continue to look the other way.

- Support organizations like the Fair Labor Association and United Students against Sweatshops, who are working to end these awful abuses.

- Finally, don’t give in to fast fashion. If it seems too cheap to be true, remember that someone, somewhere suffered to make it so. Consider repurposing, swapping, or saving up to buy non-sweatshop items. You will have the comfort of knowing you did the right thing.

The following video helps us learn more about women’s ethical and sustainable responses to oppressive global systems. How many systems can you identify that provide your clothes? What forms of power do you see women applying to change their worlds?

Learning Activities

- What is an ecological perspective? What is an empowerment perspective? What are the similarities and differences between these two perspectives?

- What are the systemic challenges facing women in a global economy? How does thinking about these challenges as being systemic, rather than as problems facing individual women, change your perspective on them—and on possible approaches to addressing these challenges?

- Working alone, with a partner, or in a small group, take a few minutes to look at the ILO InfoStories website. Choose one topic and read through it. What do you learn about women and work? How does what you learn relate to the topics discussed in this chapter? Please provide specific examples from the textbook and the website to support your assertions.

- What is care work? Take a few minutes to review the chart titled “Women Perform 72.6 Percent of Unpaid Care Work.” What do you learn about the different amount of time that men and women spend on paid and unpaid work across different regions of the world? Why is this information a key component of a transnational feminist analysis of women’s work in a global economy?

- Working in a small group, add these key terms to your glossary: ecological perspective, empowerment perspective, micro-/mezzo-/macrosystem levels, occupational segregation, Nordic model, disablism, social model of disability, medical model of disability, care work.

References

American Civil Liberties Union. 2021. “ACLU Applauds Biden Administration Order on LGBTQ Workplace Protections.” January 20, 2021. https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-applauds-biden-administration-order-lgbtq-workplace-protections.

Badgett, M. V. Lee, Andrew Park, and Andrew Flores. 2018. “Links between Economic Development and New Measures of LGBT Inclusion.” Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Global-Economy-and-LGBT-Inclusion-Mar-2018.pdf.

Beardsley, Eleanor. 2019. “In France, the #MeToo Movement Has Yet to Live Up to Women’s Hopes.” NPR. May 19, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/19/719691001/in-france-the-metoo-movement-has-yet-to-live-up-to-womens-hopes.

Berg, Peter. 2015. “Representing Worker Interests: Past, Present, and Future.” Social Service Review 89, no. 2, 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1086/681629.

Black, Sandra, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Audrey Breitwieser. 2017. “The Recent Decline in Women’s Labor Force Participation.” In The 51%: Driving Growth through Women’s Economic Participation, edited by Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and Ryan Nunn, 5-17. Washington, DC: Hamilton Project, Bookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/es_101917_the51percent_full_book.pdf.

Boris, Eileen. 2019. Making the Woman Worker: Precarious Labor and the Fight for Global Standards, 1919-2019. New York: Oxford University Press.

Boris, Eileen, and Jennifer N. Fish. 2014. “‘Slaves No More’: Making Global Labor Standards for Domestic Workers.” Feminist Studies 40, no. 2, 411–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.15767/feministstudies.40.2.411.

Brown, Colette, and Crystal Mills. 2001. “Theoretical Frameworks: Ecological Model, Strengths Perspective, and Empowerment Theory.” In Culturally Competent Practice: Skills, Interventions, and Evaluations, edited by Rowena Fong and Sharlene B. C. L. Furuto, 10-32. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Cech, Erin A., and William R. Rothwell. 2020. “LGBT Workplace Inequality in the Federal Workforce: Intersectional Processes, Organizational Contexts, and Turnover Considerations.” ILR Review 73, no. 1, 25–60. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0019793919843508.

Cravey, Altha J. 2015. “Gendered Commodity Chains: Seeing Women’s Work and Households in Global Production.” American Journal of Sociology 120, no. 5, 1578-80. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/679630.

Faue, E. 2018. Women’s ILO: Transnational Networks, Global Labour Standards, and Gender Equity, 1919 to Present, edited by Eileen Boris, Dorothea Hoehtker, and Susan Zimmerman. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Finn, Janet L. 2001. Review of Women and Power: Fighting Patriarchies and Power, by J. Townsend, E. Zapata, J. Rowlands, P. Alberti, and M. Mercado. Bulletin of Latin American Research 20, no. 2, 275-76. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3339621.

———. 2016. Just Practice: A Social Justice Approach to Social Work. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gitterman, Alex, and Carel B. Germain. 2008. The Life Model of Social Work Practice: Advances in Theory and Practice. 3rd ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. 2011. National Transgender Discrimination Survey: Executive Summary. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Exec_Summary.pdf.

Gutiérrez, Lorraine M. 1990. “Working with Women of Color: An Empowerment Perspective.” Social Work 35, no. 2, 149. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232457463_Working_with_Women_of_Color_An_Empowerment_Perspective.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2000. “Global Care Chains and Emotional Surplus Value.” In On the Edge: Living with Global Capitalism, edited by Will Hutton and Anthony Giddens, 130-46. London: Jonathan Cape.

Human Rights Campaign. 2011. Sterilization of Women and Girls with Disabilities: A Briefing Paper. Washington, DC: Human Rights Campaign. https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/11/10/sterilization-women-and-girls-disabilities.

Huq, Chaumtoli. 2019. “Women’s ‘Empowerment’ in the Bangladesh Garment Industry through Labor Organizing.” Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies 20, 130–54. http://sites.cortland.edu/wagadu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/12/v20-Huq.pdf.

ILO. International Labour Organization. 2015b. Disability Inclusion Strategy and Action Plan: 2014-2017. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—ifp_skills/documents/genericdocument/wcms_370772.pdf.

Jenkin, Matthew. 2012. “Transgender Issues in the Workplace.” The Guardian. August 9, 2012.

Manalansan, Martin Fajardo. 2008. “Queering the Chain of Care Paradigm.” Scholar and Feminist Online 6 (2008).

Nadasen, Premilla. 2017. “Rethinking Care: Arlie Hochschild and the Global Care Chain.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 45, nos. 3 and 4, 124-28.

Nunn, Ryan, and Megan Mumford. 2017. The Incomplete Progress of Women in the Labor Market. Washington, DC: Hamilton Project. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/incomplete_progress_women_in_labor_force_NunnMumford.pdf.

Peetz, David. 2019. The Realities and Futures of Work. Acton: Australia University Press. http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n5694/pdf/ch08.pdf.

Poo, Ai-jen. 2019. “A Vision for Universal Family Care: A Conversation with Ray Suarez.” YouTube video, November 22, 2019. https://youtu.be/jP-9HTDPWBI.

Rosenblad, Kajsa. 2020. “The Difference between the #MeToo Movement in Denmark and Sweden.” Scandinavia Standard. May 2, 2020. https://www.scandinaviastandard.com/the-difference-between-the-metoo-movement-in-denmark-and-sweden/.

Safe Zone Project. n.d. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://thesafezoneproject.com/.

Sagmoen, Erik B. M. 2020. Review of Protecting the Workforce: A Defense of Workers’ Rights in Global Supply Chains, by Marquita R. Walker, and The New Politics of Transnational Labor: Why Some Alliances Succeed, by Marissa Brookes. Labor Studies Journal 45, no. 3, 323–25. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0160449X20915030.

Social Protection-Human Rights. n.d. “Key Issues: Persons with Disabilities.” Accessed August 12, 2021. https://socialprotection-humanrights.org/key-issues/disadvantaged-and-vulnerable-groups/persons-with-disabilities/.

Solomon, Barbara. 1976. Black Empowerment: Social Work in Oppressed Communities. New York: Columbia University Press.

Steiger, Russell L., and P. J. Henry. 2020. “LGBT Workplace Protections as an Extension of the Protected Class Framework.” Law and Human Behavior 44, no. 4, 251–65. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32757608/.

Townsend, Janet, Pilar Alberti, Marta Mercado, Jo Rowlands, and Zapata Rowlands. 2000. Women and Power: Fighting Patriarchy and Poverty. London: Zed Books.

Trades Union Congress. 2016. Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual Harassment in the Workplace in 2016. London: Trades Union Congress. https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/SexualHarassmentreport2016.pdf.

———. 2021. Sexual Harassment of Disabled Women in the Workplace. London: Trades Union Congress. https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/sexual-harassment-disabled-women-workplace.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2020. “Goal 5: Gender Equality. Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls.” Accessed August 12, 2021. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/goal-05/.

UN Women. n.d. “What We Do: Women and Girls with Disabilities.” Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/women-and-girls-with-disabilities.

———. 2021. Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2021. Geneva: UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2021/Progress-on-the-Sustainable-Development-Goals-The-gender-snapshot-2021-en.pdf.

White House. 2021. “Executive Order on Preventing and Combating Discrimination on the Basis of Gender Identity or Sexual Orientation.” January 20, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-preventing-and-combating-discrimination-on-basis-of-gender-identity-or-sexual-orientation/.

World Bank. 2019. Women, Business, and the Law 2019: A Decade of Reform. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31327/WBL2019.pdf.

Further Reading

Acosta, Lucas. 2021. “President Biden Issues Most Substantive, Wide-Ranging LGBTQ Executive Order in U.S. History.” Human Rights Campaign. January 20, 2021. https://www.hrc.org/press-releases/president-biden-issues-most-substantive-wide-ranging-lgbtq-executive-order-in-u-s-history.

ADA.gov. n.d. “Introduction to the Americans with Disabilities Act.” US Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://beta.ada.gov/topics/intro-to-ada/.

The Atlantic. n.d. “The Top Five Issues for Working Women around the World.” Accessed November 22, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/sponsored/thomson-reuters-davos/the-top-five-issues-for-working-women-around-the-world/762/.

Bartleby Research. 2015. “There Are Different Theories, Perspectives, Practices.” Accessed November 22, 2021. https://www.bartleby.com/essay/There-Are-Different-Theories-Perspectives-Practices-FKDEBM398E7Q.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “Disability and Health Information for Women.” Last updated September 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/women.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “Disability Inclusion.” Last updated September 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability-inclusion.html.

“Ecomap Activity.” n.d. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://images.template.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/04092448/Ecomap-Activity-PDF-Format-Free-Template.pdf.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2017. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. 20th anniversary ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gutiérrez, Lorraine M., and Edith Anne Lewis. 1999. Empowering Women of Color. New York: Columbia University Press.

Human Rights Watch. 2012.“UN: Set Plan for Women, Children with Disabilities: Include People with Disabilities in Development Programs Worldwide.” September 11, 2012. https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/09/11/un-set-plan-women-children-disabilities.

ILO. International Labour Organization. 2015a. “Disability and Development: Priority Issues and Recommendations for Disability Inclusion in the Post 2015 Agenda—World of Work.” Geneva: ILO. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/hlmdd/hlmdd_ilo.pdf.

———. 2017. “The Story of Abeer Abu Ghaith: A Leading Young Palestinian Businesswoman.” YouTube video, February 2, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j-e16wN-t3o.

———. 2018a. “Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work.” Presented at the G7 Employment Task Force Meeting, Vancouver, October 2-3, 2018. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—cabinet/documents/presentation/wcms_728144.pdf.

———. 2018b. The Gender Gap in Employment: What’s Holding Women Back? Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/infostories/en-GB/Stories/Employment/barriers-women#unemployed-vulnerable.

Jambon-Puillet, Matthias, n.d. “In France, the #MeToo Movement Has Yet to Live Up to Women’s Hopes.” NPR. Accessed December 4, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/19/719691001/in-france-the-metoo-movement-has-yet-to-live-up-to-womens-hopes.

Job Accommodation Network. n.d. “Employees’ Practical Guide to Requesting and Negotiating Reasonable Accommodation under the Americans with Disabilities Act.” Accessed August 30, 2021. https://askjan.org/publications/individuals/employee-guide.cfm.

Johnson, Joshua. 2021.“Rep. David Cicilline (D-RI) on the LGBTQ+ Protections in the Equality Act.” Yahoo! News. February 20, 2021. https://news.yahoo.com/rep-david-cicilline-d-ri-052423943.html.

Lau, Tim. 2019. “Citizens United Explained.” Brennan Center for Justice. December 12, 2019. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/citizens-united-explained.

Maack, Már Másson. “Scandinavian Work Culture Is Better Than Yours—Here’s Why.” Business. February 20, 2017. https://thenextweb.com/business/2017/02/20/scandinavian-work-culture-is-better-than-yours/.