Families in a Global Context

Rebecca J. Lambert

What comes to mind when you think of family? Is it the people that you live with? Perhaps it is the people you are related to through bloodlines. Or does your family consist of a network of people you choose to consider your family? One might also consider the structure of a family. What makes a family? Is family a concept, a relation, a network? Who counts as family? Can family relationships be established as opposed to being born into? The idea of family raises many questions, and there are more factors to consider when defining family than one might initially think.

Think about the systems of power that might guide the family to which you belong. What do they look like? How are the members of your family affected by these systems? It might feel strange to think about the ways that power infiltrates and shapes family structures, but we see the effects of such systems every day, when men in a family are expected to be the protectors and breadwinners, when women are expected to be caregivers, and when it’s often assumed that ideal families consist of heterosexual married couples and their biological children.

Feminism offers a framework to examine the socially constructed ideas attached to the concept of family while coming up with alternatives for what a family can be and look like. In truth, family is different for everyone you meet, yet the version of family that has been normalized is a model of family rooted in white supremacist, colonial, patriarchal, and heteronormative ideals. One way to reimagine family is by recentering those who are often marginalized within systems of oppression. An intersectional feminist approach to families allows us to analyze how systems of power and oppression regarding gender, race, class, sexuality, and disability affect ideas about what or who constitutes a family. Feminism challenges traditional ideas of family and the idea that families exist in isolation from other social structures (Ferree 1990). Feminist sociologist Myra Marx Ferree states that “neither families nor households can be conceptualized as separate . . . spheres of distinctive relationships; both family and household are ever more firmly situated in their specific historical context, in which they take on diverse forms and significance” (1990, 879). In other words, family members experience gendered expectations tied to constructed gender roles and this positions the idea of family within frameworks of power.

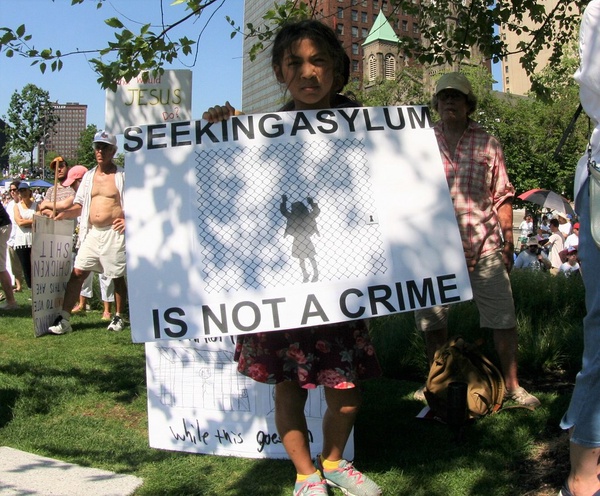

This chapter examines the ways that the concept of family is constructed, particularly through systems of oppression that are used to socialize people. The first section unpacks definitions of the concept of family and introduces alternative family forms. The following sections explore how normative family systems maintain systems of power and focus on current issues related to family, including family separation at the Mexico-US border and family experiences during the COVID-19 global pandemic. I conclude by highlighting strategies for engaging in activism that supports families in all forms.

Families, especially those related through blood and legal connections, are shaped by concepts such as inheritance and kinship. Inheritance can broadly be described as the transfer of wealth from one person to another (or others). Patrilineal and unilineal kinship structures (which are discussed in the next section) often dictate whether inheritance occurs from one or both descent lines (Lowes 2020). Inheritance is most often thought of occurring within families when an older member dies and passes their assets on to members of the younger generation. In western societies, inheritance is often split evenly among recipients (Lowes 2020). For example, countries including France, Germany, Israel, Sweden, and the United States are patriarchal societies, but there is no legal requirement for inheritance to go directly to male heirs, and asset divisions are determined by marriage associations (Lowes 2020). In other patriarchal societies such as China, inheritance transfers to the male line of descent. This structure of passing family assets through male descent lines has far-reaching implications for women and families, often resulting in less generational wealth for women.

It is also helpful to consider the idea of kinship, and how it shapes modern notions of what families look like across the world. The concept of kinship is often taken up in anthropological studies and used to describe how culture defines people’s connections to one another. This can be through blood relations, marriage, or chosen family relationships. Kinship groups are organized in many ways. For example, a unilineal descent structure represents family lineage traced through one of the parents (Lowes 2020). Within different cultural and historical contexts, there are matrilineal kinship structures and patrilineal kinship structures. Matrilineal is traced through the female family members, and patrilineal is traced through the male family members (Lowes 2020).

Kinship is closely related to descent, another concept that affects families. This is especially important because descent structures and kinship influence inheritance patterns for families. Descent recognizes connections to ancestors and often dictates inheritance structures. Often, power and family roles are attached to inheritance. Most societies are patrilineal, favoring the men in a family when it comes to inheritance. A 2009 report by the Rural Development Institute for the World Justice Project offers examples of inheritance policies in South Asia. The report states that in Pakistan, under Islamic law, “women (as wives or daughters) sharers receive half as much as their male counterparts.” Under customary law in Pakistan, inheritance of agricultural land is “decided by the personal law of the citizen” (Scalise 2009). A patrilineal family structure reifies power systems attached to men and masculine gender roles within the family.

Definitions of Family

Scholarly definitions of family are frequently attributed to scholars in the fields of sociology and anthropology. Within traditional understandings of family, familial relationships are those represented by blood or legal connections. The family is often the site of socialization, where people initially experience relationships that mimic systems of oppression that occur within society. For example, as a social system, patriarchy values male authority and rule, male dominance, and male control. Within a patriarchal family, this looks like the father or male figure of the household acting as the authority for the family. According to the cycle of socialization, families are where people are socialized or learn societal values, expectations, and norms (Adams, Bell, and Griffin 2007). The oppressive structure of patriarchal society is implemented within the family, re-creating gender oppression.

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs describes family as consisting in two forms, the nuclear family and the extended family (UN DESA n.d.). A nuclear family is frequently defined as including two adults and their children. In a society dominated by heteronormativity and patriarchy, the nuclear family is most often depicted as a heterosexual married couple and their biological children. The extended family is defined as the familial relationships outside of the nuclear family, including grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins (UN DESA 2020) These versions of family do exist but should not be set as the standard or norm for every family to meet. Many other forms of family are just as valid as the heterosexual nuclear and extended two-parent family, and they are often described as nontraditional or alternative families. Such families consist of various reimaginings of relationships considered family and the dynamics that shape those relationships. Some examples include single-parent households, same-sex couples and parents, households where women are the primary source of income, intergenerational families living together, living communities, and so many more. This is in no way an exhaustive list of alternative forms of family, as it is impossible to name all the ways people create family.

Adding to a reconceptualization of family, Family Story, a US think tank, conducts research that disrupts traditional notions of family and supports and promotes the various connections that people make in order to form family structures and kinship networks. Their mission is to “address and dismantle privilege in America . . . [and] create cutting-edge research to expose the ways family privilege causes harm and create cultural and political strategies to advance equity for all types of families” (Family Story Project, n.d.). Their research also challenges popular myths about family structures. For example, they challenge the idea that the nuclear family is the historical standard for families in the United States by pointing out that this structure of family was popularized after World War II and was only attainable for white, middle-class families. Family Story also debunks the ill-conceived idea that Black families are dysfunctional by highlighting how racism affects the way that Black parents are able to parent. These are just a couple of the myths that Family Story interrogates while offering examples of various family structures.

As mentioned, many family structures exist outside of the western idea of the nuclear family, which consists of adult parents and their children under 18 years of age living together. The notion of family is expanded when considering the role that intergenerational families play in family structures. Intergenerational families are those in which multiple generations live together for various reasons, including cultural traditions, economic concerns, or assistance with childcare, among other reasons. A report by the United Nations details various living arrangements of older adults, people over the age of 65, and points out that intergenerational families are most common in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and Latin America (UN DESA 2019). In Pakistan and Afghanistan, for example, 90 percent of people over the age of 65 live with their children or other family members (UN DESA 2019).

Intergenerational families take various forms. The nonprofit organization Generations United offers four classifications to contextualize multigenerational living. A three-generation family is defined as “one or more working-age adults, one or more of their children (who may also be adults), and either aging parent(s) or grandchildren” (Generations United 2021). Grandfamilies are composed of older adults living with their grandchildren who are under the age of 18. Two adult generations represent parents and children living together, and four (or five) generation families represent a household made up of parents, adult children and possibly their children, grandparents, and great-grandparents (Generations United 2021). These family structures are defined by blood relations, but multigenerational households composed of non-blood-related people exist too.

Families can be established through adoption, the legal process of placing a child in a home to be raised by people other than biological parents. Within the broad concept of adoption, transracial and transnational adoptions often spark much debate. The US Department of Health and Human Services describes these adoption processes as “placing a child who is of one race or ethnic group with adoptive parents of another race or ethnic group” (Child Welfare Information Gateway 1994). During the 2020 fiscal year, 1,622 transnational adoptions occurred in the United States (US Department of State, n.d.). Transracial adoption and transnational adoption are viewed in both positive and negative ways. In addition to gender, race and ethnicity shape family structures, and in terms of building families, it is important to consider the needs of those who are adopted. In Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption, feminist scholar Laura Briggs (2012) argues that transracial and transnational adoptions are more complicated than simply finding a home for a child. Briggs draws attention to the fact that adoption is entrenched in the power relations of race, class, sexuality, and international politics (5). In other words, systems of oppression affect who is allowed to adopt and which children are adopted.

Effects of Later Marriage and Childbearing in Japan

by Victoria Keenan

In Japan’s traditional patriarchal culture, women were often under intense social pressure to marry before they turned 25. In 1975, women generally had their first child before they turned 26. As a result of political and social changes, by 2017, Japanese women were marrying at around age 29 and having their first child at 30.

For many women, delaying marriage and children allows them the freedom to access further education, establish their careers, and build a sense of identity before taking on the traditional role of “mother,” in which they are expected to focus solely on the needs of the family. But the age at which a birthing person has their first child can affect whether and how many subsequent children they go on to have. As a result, women are often blamed for the country’s low birth rates, as they are seen to be pursuing western individualized values.

Women may also have fewer children than they consider ideal, as they do not feel supported by their partner, their family, the state, their employer, or society. The taxing physical and mental work of raising children later in life, along with the Japanese culture of long working hours, may limit the number of children born.

Family structures are shaped not only through cultural expectation, but also economic shifts. For example, the economic crisis of 2008 in the United States saw an increase in intergenerational households. Additionally, sub-Saharan Africa experienced an increase in multigenerational families in order to care for children that lost parents due to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s (UN DESA 2016) Most recently, families have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a 2021 report by Generations United (2021), “1 in 4 Americans are living in a household with 3 or more generations,” which is a 271 percent increase in ten years. The global pandemic is a contributing factor to that increase, with 57 percent of people surveyed saying they are living in an intergenerational home because of the pandemic.

Access and Barriers to Voluntary Tubal Ligation/Sterilization in Sub-Saharan Africa

by Abigail Manciu

Tubal ligation/sterilization, colloquially known as the act of “getting your tubes tied,” is a surgical procedure in which a woman’s fallopian tubes are blocked or cut. The procedure prevents eggs from reaching the uterus and being fertilized. As a permanent form of birth control, sterilization plays an important role in the prevention of unplanned pregnancy as well as the reduction of maternal mortality. In countries like Australia and the United States, it is difficult for young, child-free women to undergo sterilization, as many surgeons push back or refuse to perform the procedure, believing women will regret not being able to have children in the future.

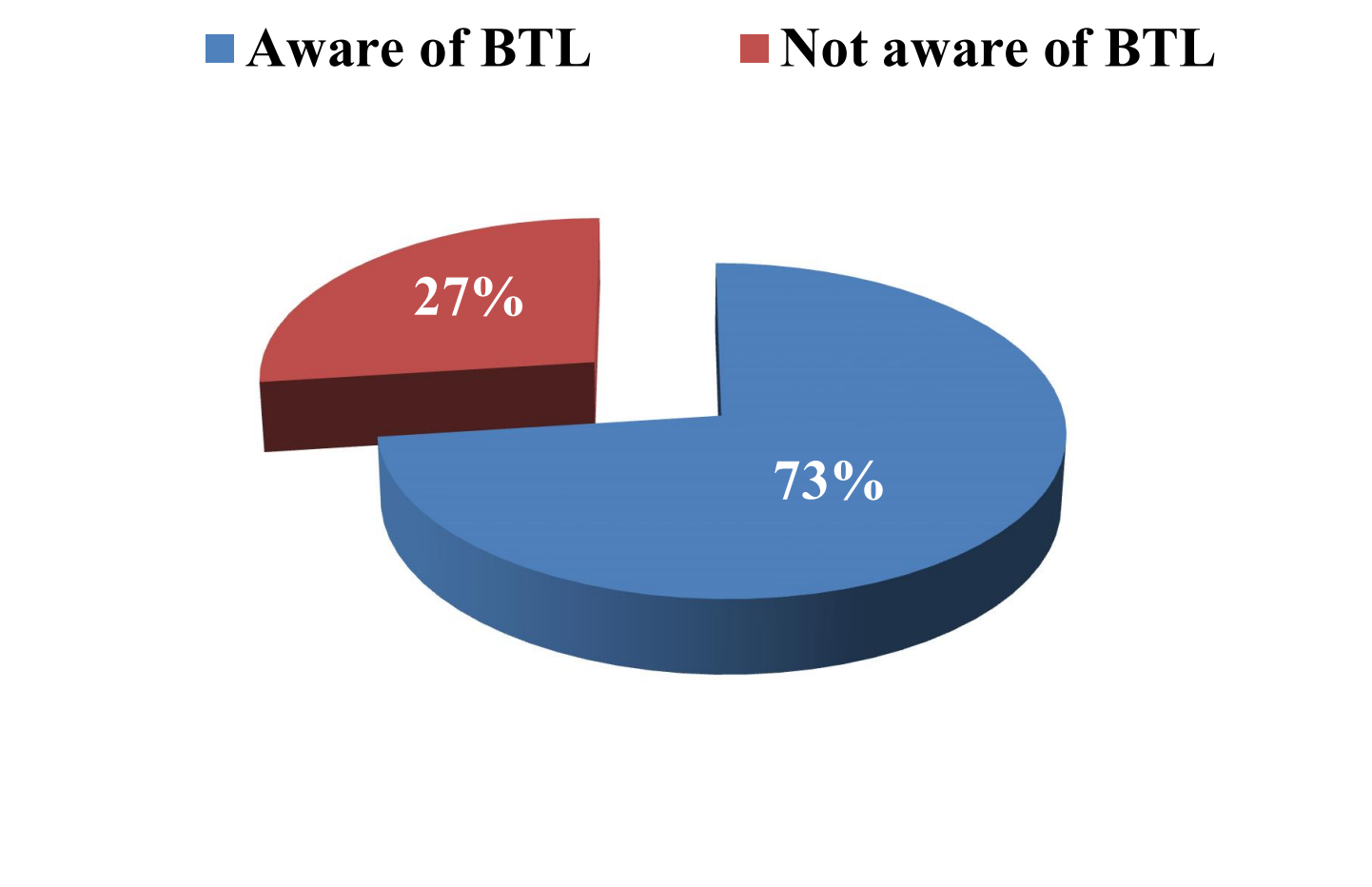

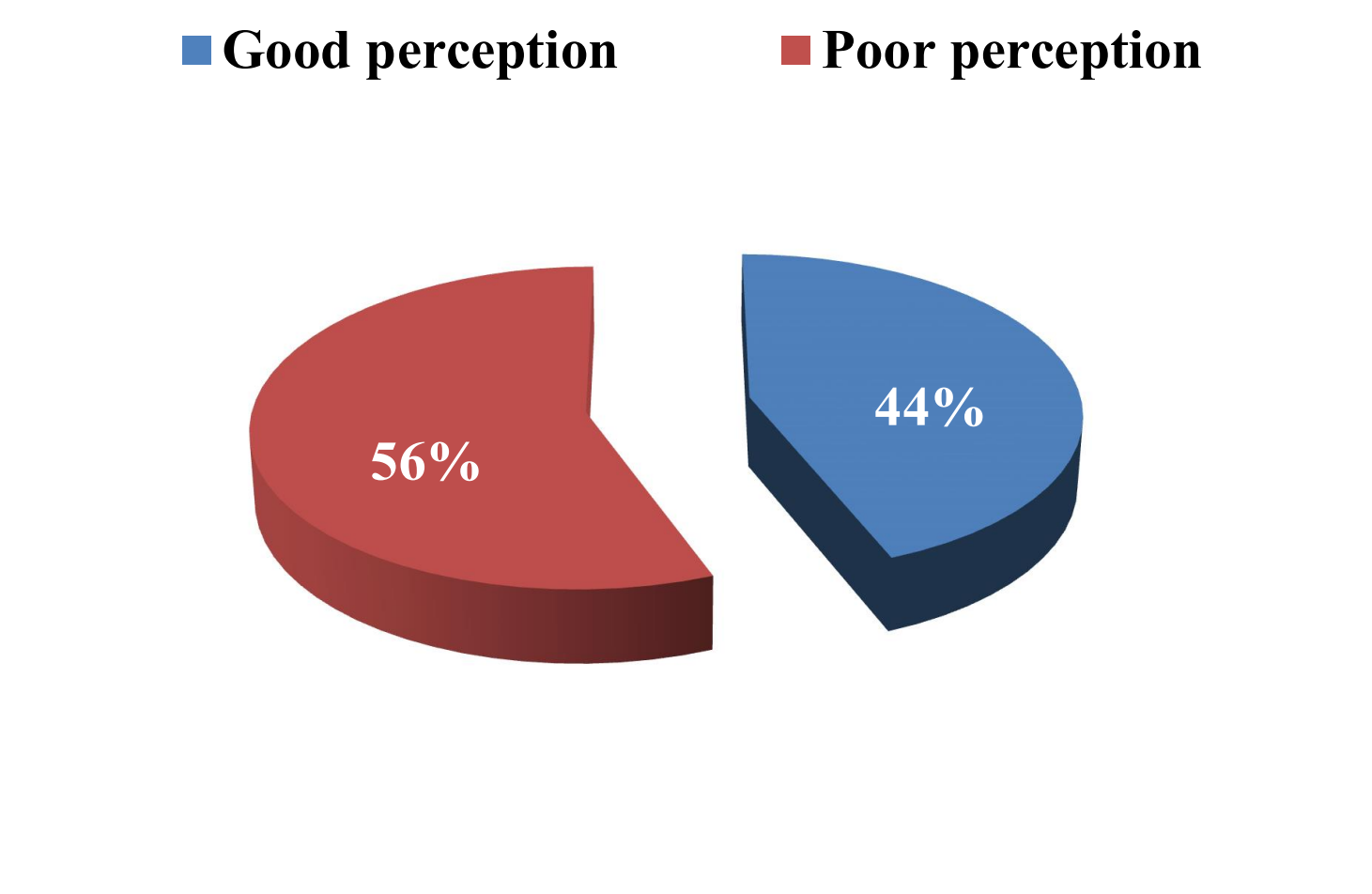

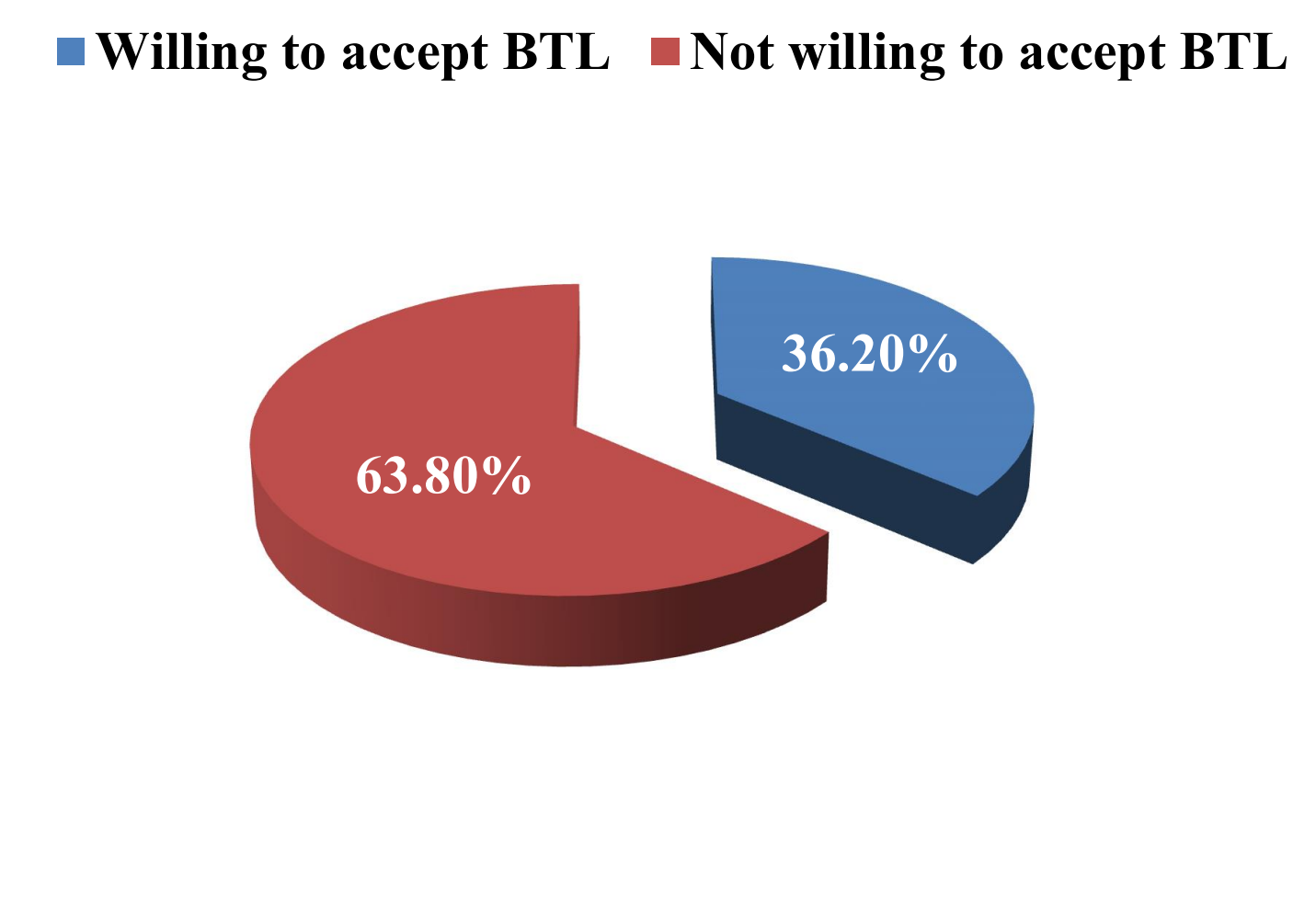

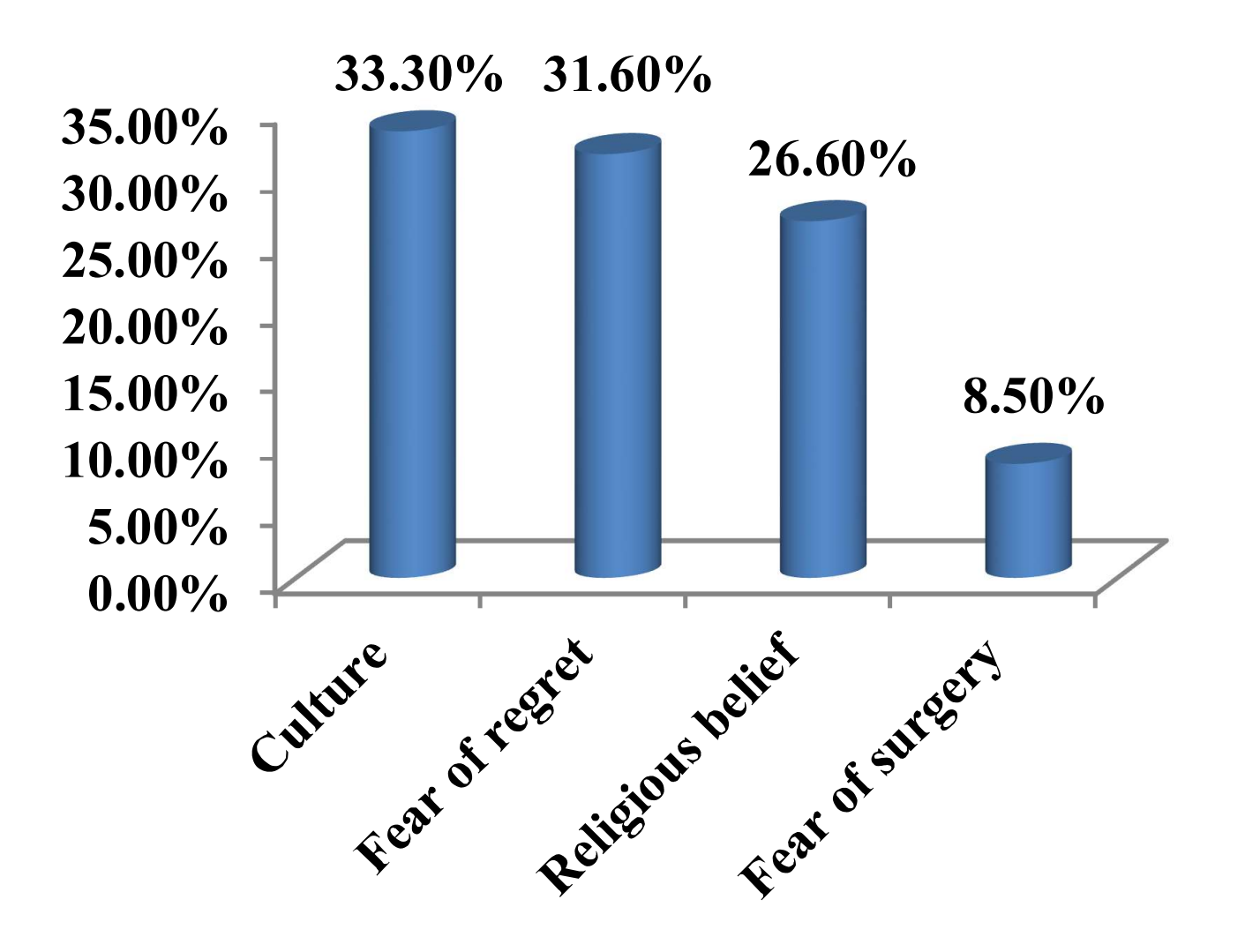

The United Nations estimates that 180 million couples worldwide have relied on surgical contraception to limit their family size. In sub-Saharan African countries like Nigeria, however, the practice of bilateral tubal ligation (BTL) is limited because of great desire for large families, cultural and religious factors, misunderstanding, and fear of health risks thought to be associated with the procedure.

The figures show the results of a survey of 26- to 30-year-old African participants on their awareness, perception, acceptance of, and reasons for not accepting BTL.

In Africa in general, the rate of BTL is low because of deep-rooted sociocultural and religious barriers, poverty, inadequate counseling, and limited facilities.

Most of the reasons given by participants in the study revealed they could not accept BTL for contraception because of cultural beliefs, fear of regret for being unable to have another child in the event an existing child is lost, and religion. More public education involving both the cultural and religious leaders as well as providing more measures to prevent infant and childhood mortality will go a long way toward increasing women’s access to options such as bilateral tubal ligation/sterilization.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a report by the Pew Research Center found that people around the world claimed that family ties have weakened (Poushter and Fetterolf 2019). From the twenty-seven countries involved in the study, 58 percent of the participants believe that family ties weakened in the past twenty years. In Tunisia, 74 percent say that family ties are weaker; 59 percent in Brazil and Kenya say it is weaker, and 83 percent in South Korea agree that family ties are weaker.

Most people in the study agreed that it was not good to see weaker family ties and expressed support for strengthening family ties. The pandemic has influenced family structures in ways that are only now being examined. For example, how did the pandemic bring people together in communities that are not related by blood or marriage?

The Effects of a Global Pandemic on Families

In a patriarchal society, women are often expected to be the caretakers for the family. Even if they work outside of the home, this caregiving role follows them when they return to the household, and they are frequently expected to do the same amount of unpaid labor in the home. Arlie Hochschild and Anne Machung (2012) have described the additional labor women are expected to perform at home as the “second shift.” The load of this additional labor is intensified in a global pandemic. The number of people living in a family’s home may grow in a pandemic, resulting in expanded caretaking responsibilities. Not only can the number of people increase, but so can the issues one is balancing in the home. What does this mean for women, children, and families in the midst of a global pandemic?

Why Is Child Care So Important?

by Sarah Baum

Imagine paying nearly 40 cents of every dollar you earn just for child care. This isn’t a nightmare; it’s a reality for many working families in New Zealand, which has an average of 37.3 percent of a couple’s earnings going toward child care. This is an almost impossible barrier to women wanting to join the workforce, and it contributes to the earned wage gap between men and women. Compared to New Zealand, the Czech Republic subsidizes child care costs and caps the parents’ outlay to a mere 2.6 percent of their income.

Child care isn’t just a passing whim, but a vital necessity in developed and developing countries alike. In the Korogocho slum in Nairobi, Kenya, 30 percent of mothers with young children were paying for child care services, showing that child care needs were already in high demand. A recent study offering child care vouchers to a group of mothers living in Korogocho found that at the end of the study, these mothers were 17.3 percent more likely than those in the control group to still be employed. The study proved that access to safe, quality child care opens opportunities for women in even the poorest regions of the world.

Beyond allowing women to join the workforce, quality, affordable child care gives children access to early education and a jumpstart to their school years. Every child deserves this start to their lives, no matter the socioeconomic status of their parents, and the only way to guarantee it is to support affordable access to quality child care on a global level.

Every continent has reported cases of COVID-19 (Slisco 2020). As of February 16, 2022, there were 450,229,635 confirmed cases of COVID-19 globally (World Health Organization, n.d.). COVID-19 has created an economic crisis that exacerbates the already unstable economic status of women around the world. The UN Women website points out that women are affected more by economic crises because they earn less money; have fewer savings; have less access to social protections; are more likely to be responsible for unpaid care work, causing them to leave the work force; and represent the majority of single-parent households (UN Women 2020).

Although women have experienced gains in joining the public workforce, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced many women back into the private sphere, with consequences that may take years to fully understand and mitigate. The full impact of the pandemic on families will take time to understand, but there is some initial research on this topic. A UN Women report titled “From Insight to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19,” offers a summary of the various effects of the pandemic on women and families that can currently be assessed. Key findings show that the global pandemic will likely increase the number of women in poverty, increase the gender gap, and intensify women’s care workload, including the work of leading their children’s education at home because of school shutdowns and online education programs (Azcona et al. 2020). Women around the world are losing their livelihoods faster because they are more exposed to hard-hit economic sectors. According to a new analysis commissioned by UN Women and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), “by 2021 around 435 million women and girls will be living on less than $1.90 a day—including 47 million pushed into poverty as a result of COVID-19” (Azcona et al. 2020).

Global Parental Leave

by Ramona Flores

Every country in the world has a policy on the national level that guarantees maternity leave for new mothers, except for Papua New Guinea, Suriname, and the United States. The United States is also one of fifteen on the list of forty-one richest countries that does not offer paternity leave.

Several major players on the global stage, including France, Russia, and the United Kingdom, have laws that ensure parental leave for both parents. The countries that offer the most comprehensive parental leave are listed in this piece from Culture Trip, with Finland offering both the longest leave, at 170 weeks, and 26 weeks of paid leave at 70 percent salary for both parents. For context, the average maternity leave in the United States, the availability and length of which is left up to the discretion of the employer, averages between 6 and 12 weeks, varying by the woman’s income. In contrast, regardless of income, fathers took an average of 1 week off for paternity leave.

Why is parental leave, both maternal and paternal, so important?

A 2020 study done by two Turkish professors published in the International Journal of Social Sciences and Education Research outlined just how essential offering both parents family leave after a child’s birth is to developing and strengthening mother-child and father-child relationships. The study also found that in countries like Greece, the Netherlands, and New Zealand, where parents are offered between 14 and 17 weeks of parental leave at full pay, more significant headway was made in combating the gender gap (wherein women tend to do more of the domestic work) that is engrained in child-rearing. To accommodate single-parent households, countries like Finland offer the single parent the amount of leave dedicated to two parents.

Paid, universal parental leave is one way to ensure that children have consistent access to the care of their parent or parents.

One way that the global pandemic affects families is through the disruption of education, particularly school closures. According to a UNESCO report, COVID-19 resulted in school closures in 185 countries. The report highlights that more than 89 percent of enrolled students were or are out of school due to the pandemic. In numeric terms, this represents 743 million girls out of school. This disruption in education is especially hard for girls in countries where extreme poverty and economic instability already pose obstacles to education. The report points out that more than 4 million girls have been forced out of school in Mali, Niger, and South Sudan, countries that already see low enrollment for girls. While there are immediate challenges to this drop in enrollment, the long-term effects of disruption in education are hard to predict. UNESCO highlights that dropout rates will increase, which will “further entrench gender gaps in education and lead to increased risk of sexual exploitation, early pregnancy and early and forced marriage” (Giannini 2020). As the pandemic continues and countries respond to this crisis in education, girls must be centered in the response.

While the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented, UNESCO offers that there are lessons to be learned from the 2014 Ebola crisis in terms of girls’ education. During the Ebola crisis in Africa, “5 million children were affected by school closures across Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, countries hardest hit by the outbreak. And poverty levels rose significantly as education was interrupted” (Giannini 2020). School closures and dropouts due to the closures left more girls at home to take on household responsibilities. UNESCO reported that this time out of school “increased girls’ vulnerability to physical and sexual abuse both by their peers and by older men, as girls were often are at home alone and unsupervised. Transactional sex was also widely reported as vulnerable girls and their families struggled to cover basic needs. As family breadwinners perished from Ebola and livelihoods were destroyed, many families chose to marry their daughters off, falsely hoping this would offer them protection” (Giannini 2020). UNESCO offers the following six “gender-responsive, evidence-based, and context-specific” actions, which may inform current recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Leverage teachers and communities: Work closely with teachers, school staff and communities to ensure inclusive methods of distance learning are adopted and communicated to call for continued investments in girls’ learning. Community sensitization on the importance of girls’ education should continue as part of any distance learning programme.

- Adopt appropriate distance learning practices: In contexts where digital solutions are less accessible, consider low-tech and gender-responsive approaches. Send reading and writing materials home and use radio and television broadcasts to reach the most marginalised. Ensure programme scheduling and learning structures are flexible and allow self-paced learning so as not to deter girls who often disproportionately shoulder the burden of care.

- Consider the gender digital divide: In contexts where digital solutions to distance learning and internet is accessible, ensure that girls are trained with the necessary digital skills, including the knowledge and skills they need to stay safe online.

- Safeguard vital services: Girls and the most vulnerable children and youth miss out on vital services when schools are closed, specifically school meals and social protection. Make schools access points for psychosocial support and food distribution, work across sectors to ensure alternative social services and deliver support over the phone, text or other forms of media.

- Engage young people: Give space to youth, particularly girls, to shape the decisions made about their education. Include them in the development of strategies and policies around school closures and distance learning based on their experiences and needs.

- Ensure return to school: Provide flexible learning approaches so that girls are not deterred from returning to school when they re-open. This includes pregnant girls and young mothers who often face stigma and discriminatory school re-entry laws that prevent them from accessing education. Allow automatic promotion and appropriate opportunities in admissions processes that recognize the particular challenges faced by girls. Catch-up courses and accelerated learning may be necessary for girls who return to school.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) communities have a long history of establishing family outside of traditional conceptions. For example, in San Francisco in 1956, the group Daughters of Bilitis held discussion groups focused on lesbian motherhood. In the 1960s and 1970s, other groups emerged to support gay and lesbian parents (Rudolph 2017), as LGBTQI+ people have experienced much discrimination as they sought to build families. It wasn’t until the 1970s that courts started to uphold custody rights for LGBTQI+ parents (Rudolph 2017). And it was only in 2015 that the US Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in all states, resulting in more (legal) opportunities for family-building in LGBTQI+ communities. Although the first gay couple to adopt a child did so in 1979, it wasn’t until 1997 that New Jersey legally allowed same-sex adoption, the first state to do so. As LGBTQI+ rights expand, so do options for creating families. The Family Equality Council released a report in 2019 titled LGBTQ Family Building Survey that offered significant findings for LGBTQI+ families in the United States. The report offers that the “number of LGBTQ-headed families . . . is set to grow dramatically in coming years,” with 77 percent already being parents or considering having children. The report also shares data on the various ways that participants discussed building their families, which include foster care, adoption, and assisted reproductive technology. As family structures continue to change and grow, so do the options for creating and choosing families.

Banning Same-Sex Couple Adoptions in Hungary

by Lauren Grant

In December 2020, Hungary’s nationalist ruling party, Fidesz, under Prime Minister Victor Orbán, passed a controversial amendment altering the constitutional definition of “family.” The new amendment bars individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+) from adopting children and from retaining recognized rights as family units under Hungarian law. The amendment defines the basis of family as “marriage and the parent-child relationship,” wherein “the mother is a woman, and the father is a man.”

Since 2009, same-sex couples in Hungary could access registered civil partnerships, granting them most of the rights and privileges of marriage, except adoption, which is exclusive to heterosexual married couples. Until the amendment, same-sex couples could apply for adoption if one partner applied as a single person. The new amendment bars unmarried couples from adopting children domestically or from abroad, a cruel attack on the rights of same-sex couples, who cannot marry under national law. Excluding “same-sex couples, single people, and unmarried different-sex couples from adopting children” under the amendment, the minister of family affairs will approve applications for adoption on a case-by-case basis. The amendment openly rejects diversity and inclusivity by mandating that children’s upbringing should be “in accordance with the values based on [Hungary’s] constitutional identity and Christian culture.”

This tightening of LGBTQI+ rights comes as Hungarian law and policy under Orbán’s hyperconservative and Christian party are persistently shrinking the country’s civil space, moving in the direction of illiberal democracy. Human Rights Watch recently described Orbán’s party as an authoritarian regime.

Hungarian civil society organizations point out that the amendment was passed during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when the rights of assembly, speech, expression, and protest have been drastically curtailed. Fighting the denial of same-sex couples’ access to adoption as well as Article XV of the Hungarian Constitution (2012), which fails to protect LGBTQI+ persons from discrimination, the oldest Hungarian LGBTQI+ human rights organization is “encouraging same-sex couples to initiate adoptions ‘as if nothing happened,’ preparing to challenge the law on the grounds of the equal treatment law.”

Countries with Legal Same-Sex Marriage

by Janet Lockhart

There have always been unions between people of the same gender; however, same-sex marriage has only been legal for about the past twenty years, first being made so in the Netherlands. Today, more than half the countries in the world that do allow same-sex marriage are in Europe, mostly western and northern countries, such as Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. The European Court of Justice declared that all members of the European Union must recognize the same-sex marriages of immigrants moving into a country, regardless of whether same-sex marriage is legal in the receiving country.

Outside Europe, same-sex marriage is legal in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, New Zealand, South Africa, the United States, and Uruguay. Most countries that have legalized same-sex marriage have done so on the basis of equal rights under their system of government. Possible next countries to legalize same-sex marriage include Chile, the Czech Republic, Japan, the Philippines, and Thailand.

Same-sex married couples still may not enjoy the same rights as opposite-sex couples; for example, the right to adopt children.

Explore further: Do some research to see whether any or all of the above countries have legalized same-sex marriage since this writing.

Family Separation

Politics, elected officials, and the policies implemented in response to migration and immigration practices can have a profound effect on families. Family separation occurs when people seek to enter a country and are separated from their children or other family members while the immigration process continues. While family separation is not a new phenomenon, it has been exacerbated in recent years. The family separation occurring at the Mexico-US border is a result of the policy changes implemented by the Trump administration of the United States (National Immigration Forum 2018). This practice became particularly rampant at the Mexico-US border in 2017 after the Trump administration instituted a “zero tolerance” policy regarding immigration. This policy allowed for the US Department of Justice to file criminal charges against every adult who crossed the border into to the United States without legal documentation (Alvarez 2020). Families were separated because a previous policy, the 1997 Flores Settlement Agreement, prohibited detaining children in adult facilities (National Immigration Forum 2018). Parents were forcibly separated from their children as they awaited the next steps in the immigration process, which often resulted in their deportation. Once separated, children were taken to and held in separate detention facilities. Despite a directive to reunite children with their parents, hundreds of children are still separated from their parents (Dickerson 2020).

Many expected that the violent immigration and family separation policies of the Trump administration would end once Joe Biden became president of the United States. When Biden took office, he signed various executive orders focused on immigration. In particular, Biden implemented a task force to reunite families that were separated at the border (Rodriguez 2021). In an attempt to undo the policies of the previous administration, Biden’s orders focus on a family reunification process that will make recommendations for how to reunite the more than six hundred children still separated from their families (Rodriguez 2021).

Even with this current directive to end family separation, the effects of such actions are traumatic for children and families, and it is critical to examine the ways that power and privilege operate within immigration policies in order to highlight why certain families experience this type of separation. Discussions of immigration are often framed around terms such as “legal” and “illegal,” constructing a system of power between those assigned to each of these categories. In the book Borders of Belonging: Struggle and Solidarity in Mixed-Status Immigrant Families (2019), scholar Heide Casteñeda explores the way that illegality is constructed for immigrant families. She defines the term illegality to “refer to a sociopolitical condition, juridical status, and relationship to the state” (5). In this context, illegal is not simply something that is against the law but situates an individual within systems of power. Casteñeda’s analysis helps to center the family and enables an examination of the impact of immigration policies—or, often, anti-immigrant policies—on families, not just individuals.

The National Council on Family Relations (n.d.) put together resources that describe the negative impact of separating families at the Mexico-US border. These effects range from psychological impacts such as depression, fear, and anxiety, to academic challenges, to behavioral issues. The impact of family separation is both immediate and long-term, although it is hard to know the full impact of such policies on children and their families.

Feminist scholars Eithne Luibhéid and Karma Chávez write that “except for those who can show that they fit into a narrow spectrum of state-designated family ties, skill sets, large bank accounts, or protection needs, possibilities for acquiring legal status have been greatly reduced or entirely cut” (Luibhéid and Chávez 2020, 1). Often lost in the mainstream narrative of family separation are the effects of harmful immigration policies on LGBTQI+ migrants, their families, and communities of people that often do not fit into state-defined systems. Scholar Suyapa G. Portillo Villeda (2020) conducted research on the immigration process for queer and trans people from Honduras. In the essay “Central American Migrants: LGBTQI Asylum Cases Seeking Justice and Making History,” Villeda argues that LGBTQI+ immigrants must be included in any sort of immigration reform in order for policies to be useful in preventing harm to queer and trans migrants. An important point that Villeda makes is that the experiences of LGBTQI+ migrants are often erased, increasing vulnerability. For example, trans migrants are often misgendered and sent through the immigration process according to the gender they were assigned at birth, resulting in additional mistreatment.

The issue of forced separation is critical for any family that does not fit the norm, and for communities that create family outside of the traditional conception of blood-related family. Including various family structures within immigration policies ensures that people are not stripped away from those that offer the support and care they need as they move into new spaces and create home.

Strategies to Support Families

Various organizations exist around the world to support and advocate for families. Advocacy efforts may be specific to a region, or they may be more broad and work globally for a range of issues. For example, the Family Equality Council (n.d.) seeks “to advance legal and lived equality for LGBTQ families, and for those who wish to form them, through building community, changing hearts and minds, and driving policy change.” This organization covers a wide range of issues that affect LGBTQI+ families, including adoption and foster care, parental supports, transgender rights, and fertility.

There are various ways that social justice efforts can support families. Another example of an organization that supports families is RAICES, the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services. Based in Texas in the United States, the organization’s mission is to “defend the rights of immigrants and refugees, empower individuals, families, and communities, and advocate for liberty and justice” (RAICES, n.d.). The organization offers legal services to immigrant and refugee families, having established a bond fund that secures the release of people from US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention and trained additional lawyers to help families being detained at the Mexico-US border. Activism is a vital component of feminist movement, and advocating for the health and well-being of families is an important issue in feminist organizing. An intersectional approach to activism and issue advocacy is also a core component of feminist movement.

Learning Activities

- Lambert begins the chapter with questions about how readers think about family. How do you define the concept of family? What does Lambert mean when she argues that families are shaped by systems of power? According to Lambert, what concept of family has been normalized? How is the normalized family a system of power? How does it support other systems of power?

- Lambert discusses the organization Family Story, whose mission is to “address and dismantle privilege in America . . . [and] create cutting-edge research to expose the ways family privilege causes harm and create cultural and political strategies to advance equity for all types of families” (familystoryproject.org). Working alone, with a partner, or in a small group, visit the Family Story website. How does Family Story challenge myths about family structures? Choose at least one family myth that the organization challenges, and explain how Family Story does so. How do Family Story’s challenges to family myths also challenge structures of power?

- How has the global COVID-19 pandemic challenged and/or changed family structures, according to Lambert?

- How and why do US immigration policies negatively affect immigrant families, according to Lambert? What challenges do queer and trans migrants face?

- Lambert discusses activist organizations that support and advocate for families, such as The Family Equality Council and RAICES. Working alone, with a partner, or in a small group, review the website for one of these organizations. What kinds of activist work does the organization engage in? How does the organization’s activism challenge and/or uphold traditional definitions of family?

- Working in a small group, add these terms to your glossary: inheritance, kinship, matrilineal, patrilineal, nuclear family, extended family, intergenerational family, transracial adoption, transnational adoption.

References

Adams, Maurianne, Lee Anne Bell, and Pat Griffin, eds. 2007. Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice. New York: Routledge.

Alvarez, Priscilla. 2020. “Family Separation and the Trump Administration’s Immigration Legacy.” CNN Politics. October 7, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/07/politics/trump-family-separation/.

Azcona, Ginette, Antra Bhatt, Jessamyn Encarnacion, Juncal Plazaola-Castaño, Papa Seck, Silke Staab, and Laura Turquet. 2020. From Insights to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19. New York: UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19.

Briggs, Laura. 2012. Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Castañeda, Heide. 2019. Borders of Belonging: Struggle and Solidarity in Mixed-Status Immigrant Families. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Child Welfare Information Gateway. 1994. Transracial and Transcultural Adoption. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/f_trans.pdf.

Dickerson, Caitlin. 2020. “Parents of 545 Children Separated at the Border Cannot Be Found.” New York Times. October 21, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/21/us/migrant-children-separated.html.

Family Equality Council. 2019. LGBTQ Family Building Survey January 2019. New York: Family Equality Council. https://www.familyequality.org/resources/lgbtq-family-building-survey/.

———. n.d. “Who We Are: Our Mission.” Family Equality Council. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://www.familyequality.org/about-us/who-we-are/.

Family Story Project. n.d. “Resources.” Family Story Project. Accessed September 28, 2021. www.familystoryproject.org/resources.

Ferree, Myra Marx. 1990. “Beyond Separate Spheres: Feminism and Family Research.” Journal of Marriage and Family 52, no. 4, 866.

Generations United. 2021. Fact Sheet: Multigenerational Households. Multigenerational Living Is on the Rise and Here to Stay. Washington, DC: Generations United. https://www.gu.org/app/uploads/2021/04/21-MG-Family-Report-FactSheet.pdf.

Giannini, Stefania, and Anne-Birgitte Albrectsen. 2020. “Covid-19 School Closures around the World Will Hit Girls Hardest.” UNESCO News. March 31, 2020. https://en.unesco.org/news/covid-19-school-closures-around-world-will-hit-girls-hardest.

Hochschild, Arlie, and Anne Machung. 2012. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. New York: Penguin.

Lowes, Sara. 2020. “Kinship Structure and Women: Evidence from Economics.” Daedalus 149, no. 1, 119–33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48563036.

Luibhéid, Eithne, and Karma R. Chávez, eds. 2020. Queer and Trans Migrations: Dynamics of Illegalization, Detention, and Deportation. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

National Council on Family Relations. n.d. “Resource Collection: Racism and Racial Violence.” National Council on Family Relations. Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.ncfr.org/.

National Immigration Forum. 2018. “Fact Sheet: Family Separation at the U.S.-Mexico Border.” National Immigration Forum. Updated July 27, 2018. https://immigrationforum.org/article/factsheet-family-separation-at-the-u-s-mexico-border/.

Portillo Villeda, Suyapa G. 2020. “Central American Migrants: LGBTI Asylum Cases Seeking Justice and Making History.” In Queer and Trans Migrations: Dynamics of Illegalization, Detention, and Deportation, edited by Eithne Luibhéid and Karma R. Chávez, 67-73. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Poushter, Jacob, and Janelle Fetterolf. 2019. A Changing World: Global Views on Diversity, Gender Equality, Family Life and the Importance of Religion. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/04/22/how-people-around-the-world-view-family-ties-in-their-countries/.

RAICES. Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services. n.d. “Our Mission.” Accessed October 1, 2021. https://www.raicestexas.org/our-mission/.

Rodriguez, Sabrina. 2021. “Biden Signs Executive Orders on Family Separation and Asylum.” Politico. February 2, 2021. https://www.politico.com/news/2021/02/02/biden-executive-orders-family-separation-464816.

Rudolph, Dana. 2017. “A Very Brief History of LGBTQ Parenting.” Family Equality Council. October 20, 2017. https://www.familyequality.org/2017/10/20/a-very-brief-history-of-lgbtq-parenting/.

Scalise, Elisa. 2009. Women’s Inheritance Rights to Land and Property in South Asia: A Study of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Brandon, MB: Rural Development Institute, Brandon University. https://cdn.landesa.org/wp-content/uploads/WJF-Womens-Inheritance-Six-South-Asian-Countries.FINAL_12-15-09.pdf.

Slisco, Aila. 2020. “COVID-19 Strikes Antarctica, Its 7th Continent, as Chilean Base Hit with Virus.” Newsweek. December 22, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/covid-19-strikes-antarctica-its-7th-continent-chilean-base-hit-virus-1556556.

UN DESA. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. n.d. “Publications: Major Trends Affecting Families.” Accessed November 4, 2021. https://www.un.org/development/desa/family/publications/major-trends-affecting-families.html.

———. 2016. “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Growing Population of Older Persons.” Population Facts 1, 1-2. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/popfacts/PopFacts_2016-1.pdf.

———. 2019. “Living Arrangements of Older Persons around the World.” Population Facts 2, 1-5. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/popfacts/PopFacts_2019-2.pdf.

———. 2020. World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights: Living Arrangements of Older Persons. ST/ESA/SER.A/451. New York: UN DESA Population Division. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd-2020_world_population_ageing_highlights.pdf.

UN Women. 2020. “COVID-19 and Its Economic Toll on Women: The Story behind the Numbers.” September 16, 2020. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/9/feature-covid-19-economic-impacts-on-women.

US Department of State. n.d. “Adoption Statistics.” Accessed September 28, 2021. https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/Intercountry-Adoption/adopt_ref/adoption-statistics-esri.html?wcmmode=disabled.

World Health Organization. n.d. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic.” Accessed March 13, 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

Image Attributions

7.1 Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

7.2 Photo by Jordan Whitt on Unsplash

7.3 Photo by Husniati Salma on Unsplash

7.4 “Rally against Family Separation – Cleveland, Ohio” by kimmy aoyama is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

7.5 “Rally against Family Separation – Cleveland, Ohio” by kimmy aoyama is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

7.6 “LGBT Families for Immigration Reform” by ep_jhu is licensed under CC BY 2.0

7.s6.1 “Figure 1” by Ahmed Yakubu is licensed under CC BY-NC

7.s6.2 “Figure 2” by Ahmed Yakubu is licensed under CC BY-NC

7.s6.3 “Figure 3” by AhmedYakubu is licensed under CC BY-NC

7.s6.4 “Figure 4” by Ahmed Yakubu is licensed under CC BY-NC