Women’s Activism Worldwide

Khatera Afghan and Folah Fletcher

When I dare to be powerful, to use my strength in the service of my vision, then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid. Your silence will not protect you.

—Audre Lorde (1977)

In the late 1960s and 1970s, feminist “consciousness-raising efforts” called women’s attention to the historical exclusion of their experiences and voices from public arenas. As a result, women began to question the production of social and material knowledge that centered on the perspectives and interests of men (Hesse-Biber and Leavy 2007). In societies classified by gender, race, class, and sexuality, knowledge claimed by historically marginalized people, such as women, becomes silent or “subjugated knowledge” (Hesse-Biber and Leavy 2007).

According to feminist historian Elsa Barkley Brown, social movements and identities are not distinct from each other, as we sometimes assume in contemporary culture. She argues that we need to consider queer social movements and identities as being related to help understand how privilege and inequality are connected, and how social movements have traditionally linked the stories of people of color and feminists fighting for justice (Brown 1992, 297).

Feminists and historians have split the history of the movement in the United States into three “waves”: The first wave relates specifically to the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century women’s liberation movement, which was concerned primarily with the right of women to vote (Staggenborg and Taylor 2005). The second wave refers to the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s, which advocated for women’s legal and social rights. The third wave refers to a continuation of second-wave feminism, starting in the 1990s, and including a backlash to the second wave’s perceived inadequacies (Staggenborg and Taylor 2005, 49).

The use of the terms first wave, second wave, and third wave to describe feminist resistance is controversial, as it implies each wave of activism prioritized different concerns. The waves were not mutually exclusive or completely distinct. Rather, they influence each other not only in the sense that earlier feminist activism has in many ways made contemporary feminist work possible, but also that contemporary feminist activism affects the way we think about past activism (Davis 2002, 73-78). A focus only on famous leaders and events can obscure the many people and activities engaged in daily resistance and community organization.

Further, the “wave” metaphor is problematic because it focuses primarily on the activities of US women who were mostly white, heterosexual, and middle class. It does not acknowledge the resistance efforts of Indigenous women before, during, and after the colonization of the continent by Europeans; of Black women and other people of color in the United States; of women who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, or intersex plus (LGBTQI+); nor women in most of the rest of the world. Concentrating on the most “mainstream” figures, political events, and social movements advances only one unique lens of history. Transnational activism demonstrates a reframing toward global solidarity while centering the lived experiences of women and their priorities.

Feminists have continued to challenge patriarchy by questioning exploitation, harassment, violence, and objectification in the various areas of their lives: work, home, family, and public environments. While some resistance to oppression arises in subtle or individual ways, for feminist-identified women, collective resistance is also a powerful way to question current power structures. Women and their allies often build major feminist movements that collectively question the systemic roots of oppression (Brown 1992). Yang (2016) affirms that the waves of social feminist movements have generated only partial changes in systematic oppression against women and girls globally. Nevertheless, feminist social movements have implemented several significant changes in laws, social norms, and definitions of gender roles (Yang 2016, 13).

The Pussyhat

by Charissa V. Jones

The Pussyhat is a bright-pink knitted cap with cat ears that came to symbolize the Women’s March in Washington, DC, on January 21, 2017, the day after Donald Trump was inaugurated. Cofounders Krista Suh and Jayna Zweiman wanted the hats to be a symbol that reclaimed the derogatory term “pussy” after Trump’s infamous Access Hollywood remark that women should let him “grab them by the pussy.” Suh and Zweiman chose pink, traditionally associated with femininity, because they wanted to visibly stand up for women’s rights. The pattern was available for free online; craft stores couldn’t keep the color in stock as women around the country created knitting circles to make the hats.

While the hats did unite some people of all genders around women’s issues, for others, the sea of pink also brought up the lack of intersectionality within feminist movements, becoming synonymous with white feminists, trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs), and sex worker-exclusionary radical feminists (SWERFs). These narratives were destructive: Not everyone who doesn’t identify as a man has a pussy. Not every pussy is pink. When marginalized communities challenged the white, cisgender narratives of the Pussyhat and the March, supporters called them divisive. But Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) don’t owe anyone thanks for acting as allies. They continue to bring to light how being a non-male person is affected by racism, sexism, Islamophobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other social justice issues.

Transnational Feminist Activism

Transnational feminism emerged as a response to the First World versus Third World split; that is, the recognition that women’s experiences, priorities, and concerns are different in different parts of the world. This first came forward during the United Nations’ (UN) Decade for Women (1975-85) World Conferences: Mexico City in 1975, Copenhagen in 1980, Nairobi in 1985, and Beijing in 1995. It was after the Beijing conference that the term transnational feminism and its political agenda for global justice came to be fully realized and widely embraced (Desai 2005). Transnational feminism pursues social justice by developing alliances that challenge gender, racial, and cultural essentialist binaries (e.g., the idea that all women—and also all men—have one basic, unchangeable nature) (Grewal and Kaplan 1994).

As an anti-domination, anti-oppression activist movement, transnational feminism promotes a focus on the interlocking systems of oppression (racism, classism, etc.) and the ways they shape gender relations worldwide (Mohanty 2003; McLaren 2017). By challenging the historically rooted essentialist ways of thinking that erase differences and diversity among women, transnational feminism acknowledges and bravely embraces these differences (Mohanty 1988; Grewal and Kaplan 1994). Transnational feminism converts differences into alliances that promote conversations to help heal the First World-Third World split (Mohanty 2003; McLaren 2017) and to produce meaningful changes for women globally. Engaging with the nuanced realities of the world, transnational feminists create cross-border activism with a focus on understanding the differences in women’s experiences worldwide (Mohanty 2003; Moghadam 2005; McLaren 2017).

The construction of transnational coalitions and of broader ways of thinking about knowledge recognizes women do not have the same pain or needs and acknowledges our varied pasts and historical conditions (Mohanty 2003). We try to focus our activism toward social justice that is inclusive and attainable (hooks 2015). Because it values the contributions differences make to solidarity, transnational feminism promotes reflective alliances among diverse women who have chosen to work and fight together for their common interests (Mohanty 2003).

Women with Disabilities Advocating for Inclusion

by Shannon Garvin

Human Rights Watch estimates that about 300 million women around the world have mental or physical disabilities. In poorer nations, women comprise 75 percent of the population with disabilities. In 2006, 164 nations signed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Globally, the United Nations estimates that less than 5 percent of disabled persons have access to education. Disabled women are half as likely to find employment as men.

Local support of disabled persons can be challenging because of overlapping issues of gender, race, socioeconomics, available resources, education, attitudes toward disabilities, and the specific disability affecting a person. But women with disabilities and their allies are increasingly advocating for equity and inclusion for themselves in all aspects of life.

In east Africa, the Ethiopian Women with Disabilities National Association (EWDNA) works with women who are Deaf or Blind, or who have autism or an intellectual disability, to provide vital services such as skills training, work opportunities, and integration into the local community. In Kenya, This-Ability collaborates with other organizations to increase visibility and inclusion for women and girls with disabilities in everything from access to health care, to representation in websites and other media, to participation in sports.

Across Oceania, the Pacific Disability Forum advocates for all people with disabilities by seeking to ensure governments honor the provisions of the CRPD. Vanuatu’s Volley4Change and Papua New Guinea’s Gymbad offer sports programs designed to include people with disabilities, especially women and girls. Women with Disabilities Australia advocates for “women, girls, feminine identifying and non-binary people living with disabilities” through leadership trainings, information on an accessible website, and advocacy with governments.

These are just a few of the organizations working for the rights of women and girls with disabilities worldwide. To see a more comprehensive map of these organizations, click on the Women Enabled International link here.

Under the umbrella of transnational feminism, activists and advocates mobilize transnational feminist networks (TAFs) to work toward resisting repressive norms and institutions worldwide. TAFs promote:

- “feminism against neoliberalism,” by contesting global economic systems and policies that promote economic privatization and free-market practices that lead to greater gender inequalities;

- “feminism against imperialism and war,” by opposing imperialism, global clashes, and gendered war practices;

- “feminism against fundamentalism,” by challenging the repercussions of religious practices that deny gender equality and women’s rights; and

- “feminist humanitarianism,” by addressing women’s basic needs and strategic interests worldwide. (Lee and Shaw 2011)

To achieve their goals, transnational feminists call for cross-border solidarity, where solidarity is a mutual and accountable relationship that bonds different people across their common interests (Lee and Shaw 2011). We live in a transnational time where everything from ideas, to capital, to fear, to violence flows across state boundaries. This fluidity shapes women’s experiences internationally (Naples 2009). Addressing transnational issues, especially gender inequalities, requires a dialogue that recognizes and respects, rather than silences or ignores, differences (Grewal and Kaplan 1994; Mohanty 2003; hooks 2015).

Transnational solidarity requires women to build effective, inclusive, and politically strategic bonds, understanding that only discussions of women’s differing ideologies lead to honest cross-national communications (Grewal and Kaplan 1994). Building these bonds depends on the extent of our willingness to acknowledge and bravely confront rather than fear our differences (and move beyond pretending to be united) to overcome our biases, competitiveness, fears, and hostilities (hooks 2015).

Building transnational solidarity based on particulars/differences has emerged from active struggle (rather than common oppression). It is in this context that we will build on commitment, effort, and acknowledgment that women can have a common goal: social justice (Mohanty 2003; hooks 2015).

In sum, although women worldwide commonly experience gendered oppression, their issues and circumstances differ within and across cultures (Afshar 1998), which makes them more diverse than similar in their experiences, needs, and interests. Promoting social justice through a transnational alliance requires us to move beyond our assumptions of an “enforced commonality of oppression” (Mohanty 2003, 7), including by leveraging the various forms of feminist activism to dismantle the universalized, homogenous category of “woman” (Mohanty 2003). To avoid creating new categories that are not only abstract but exclusive, transnational feminism has to be open and receptive to self-reflection—knowing that this reflectiveness is important for the social transformation we are committed to promoting (Grewal and Kaplan 1994).

A New Era of Global Transnational Activism

Transnational feminist activists promote social and gender justice by actively renegotiating gender power relations; building cross-national coalitions; engaging in and influencing international policies, laws, and organizations on women’s rights issues; lobbying governments to support and promote social and gender equalities; and supporting women’s protest movements and cyber-activism (Desai 2005; Moghadam 2005).

For example, transnational African feminist activists have strengthened their ties with women worldwide by engaging in cyber-activism in the form of blogging, which they use to speak up, share their experiences, seek opportunities for alliance, and promote gender equality (Nouraie-Simone 2005). According to one blogger, “the presence of women bloggers is in itself a positive step towards addressing issues of gender equality” (Somolu 2007). Living in a technologically connected, globalized, and constantly changing world, where things happen with the click of a mouse, these women use cyberspace to break their silence, develop collective resistance, share their experiences, participate in public spaces, explore (and enjoy) their changing identities, and ultimately seek social transformation (Nouraie-Simone 2005).

Likewise, Muslim women’s activism is manifested in their revolutionary presence on the Internet. Muslim women’s activist engagement in social media not only shaped the “Arab Spring” (a series of pro-democratic, anti-authoritarian protests in the Middle East and North Africa in the early 2010s), but also shifted the Middle East political landscape (Radsch 2012). In addition to fighting from beyond their computer screens, most of these women combined their cyber-activism with offline activism, resulting in broader media coverage and their participation in the uprisings (Nouraie-Simone 2005). As one of the activists said, “cyber-activism is not just working behind the screen, it is also smelling the tear gas and facing the security forces’ live ammunition” (Radsch 2012, 19). Arab cyber-activism exemplifies Muslim women’s agency and emerging voices for social transformation, their feminist maneuvering from within oppression, and their active participation in transnational activism.

Like Arab women, the young female generation of Iran uses the Internet as a liberatory tool to resist subjugation and to actively participate in ongoing transnational movements. Iranian women rely on weblogs to freely speak their minds while challenging historical gendered politics in their society. As an empowering substitute to the current politically manipulated and male-dominated physical public sphere, Iranian women use cyberspace to explore and enjoy new territories of liberation, uncensored self-expression, and nonbinary identities (Nouraie-Simone 2005). The Internet not only provides women with access to the outside world; it also helps them to become voices of change that are hard to silence (Somolu 2007). The cyber-activists’ blogs illustrate Iranian women’s self-advocacy, resistance in the face of social injustice, participation in feminist discourse, and commitment to social change. One of the web activists raises her voice and shares her feelings and frustrations:

I have not been born as subordinate sex, or as biologically inferior. I have been brought up as one with the allocation of roles and expectations. I am a product of cultural biases of a patriarchal order that talks about an inherently womanly nature so that when a girl climbs trees or jumps up and down, she is warned or bullied—told that a girl is not supposed to jump from heights—to safeguard a little piece of skin (hymen) as proof of her honor. At 16, I wanted to become a guerrilla fighter, instead, I became a woman warrior fighting with my pen—a powerful instrument that cannot be silenced. (Nouraie-Simone 2005, 64-65)

In addition to their cyber-activism, Muslim women have revolutionized the digital galaxy. They have begun to reclaim a space in the digital world by pursuing a career shift from “off-camera” to “on-camera.” From the authors’ points of view, Muslim women’s digital activism is evident in the growing number of Muslim women students who have chosen to pursue careers in electronic media, journalism, and cinema. According to a 19-year-old student of media studies in Dubai, “I noticed that there are few women in the field of journalism, and since I have that kind of personality, I decided to pursue it” (Ismail and Ali 2008).

As a voice of change, Egyptians mobilize digital space to change Arabs’ traditional gender perceptions, understanding of social norms, and power relations (Mernissi 2004). As such, some Egyptian television hosts have used digital space to facilitate conversations about topics that are not generally discussed in public in the Muslim world. For example, in 2017, the Egyptian TV presenter Doaa Salah, on the Al-Nahar network, asked viewers if they had considered premarital sex and suggested that women could temporarily get married to have children. Although Salah’s statements were not well received by some people, especially the authorities who later sentenced her to three years in prison, Salah broke a traditional patriarchal taboo in Egypt (BBC News 2017) and provided an example of resistance to other women.

Loujan al-Hathloul

by Miranda Findlay

On February 11, 2021, Saudi Arabian women’s rights activist Loujan al-Hathloul was released from prison. Al-Hathoul is known for challenging the ban on women driving and the male guardianship laws that require women to receive the consent of a male relative on decisions related to issues such as education. Under the strict gender segregation of Wahhabism, the form of Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia, the idea of a woman behind the wheel was seen as sacrilegious. Saudi Arabia continued to ban women from driving until 2018, even though demonstrations against the ban had occurred previously; for example, in November 1990, forty-seven Saudi women had driven their cars in protest in Riyadh.

Al-Hathloul has been arrested several times, most recently on May 15, 2018, for her involvement in the women’s rights campaign. In June 2018, even after Saudi Arabian women were granted the right to drive, al-Hathloul remained under arrest. In 2021, she was finally released by the Saudi Arabian government in response to the Biden administration’s criticisms of the country’s human rights violations. Al-Hathloul was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 and 2020, and she was awarded the 2020 Václav Havel Human Rights Prize in April 2021.

Breaking Silence

Third World feminist scholars and activists seek to produce new knowledge, “decolonializing” discourse that ignores Third World women’s Indigenous feminist history and resistance. In an effort to cure the First World-Third World split, Third World scholars call for the reconstruction of feminist essentialist thought. They also warn against falling into the trap of anti-western sentiment that may divert focus from the struggle and feed into the production of inaccurate, homogenous knowledge (Said 1978; Mohanty 1988, 2003; Grewal and Kaplan 1994; Abu-Lughod 2001). It is crucial to understand how the colonial power system functions in the global context in general and in the Third World in particular, and to challenge it.

In her meticulous analysis “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses,” Chandra Mohanty criticizes western essentialist feminist discourse, which defines Third World women as a monolithic and “universal” group with identical visions, goals, needs, and interests. The author states that such binary discourse creates a “paternalistic attitude towards women in the third world” (Mohanty 1988, 378). It also conceptualizes Third World women as passive and victimized objects devoid of agency and the ability to speak for themselves, needing to be saved and represented by western women (Mohanty 1988).

Like Mohanty, Uma Narayan challenges ethnocentric feminist attitudes to Third World cultures and traditions. The author criticizes the “missionary framework” of western feminists, in which Third World women are presented as the victims of their own cultures, who need to be rescued by First World women. Ignoring the fact that cultural traditions arise and develop in historical contexts, dominant parts of the West continue to perceive and treat Third World traditions as changeless, “perennially in place,” making Third World nations “places with no history” (Narayan 1997, 48-49). In her critiques, the author also calls for the deconstruction of the term “Westernization” and its perceived meaning. For Narayan the term is widely used as a “strategy of dismissal,” where Third World feminists who fight against patriarchal norms are viewed as westernized and “traitors to their communities” (Narayan 1997, 31).

Like non-Muslim feminists, Muslim women in the Third World, particularly feminist warriors, promote social transformation by developing actions from “within subordination.” As a force for change, Muslim women have been an active part of cross-national feminist movements, which have enabled them to break through their cultural, national, and regional boundaries (Nouraie-Simone 2005). In their quest for social transformation, Muslim women (whether associated with Islamic or secular feminisms) have responded to oppression that denies Muslim women a voice, agency, and intellectual and political maturity.[1] Islamic feminists in the West use their religion to seek social transformation by actively engaging in contemporary feminist discourses about Muslim women.

Feminist Activism in Okinawa: Invoking Unai

by Risako Sakai

Okinawan women historically played important cultural roles such as priestesses (nūru) and spiritual guides (e.g., kaminchu) who communicated with ancestors and nature gods. But the invasion and colonization by Japan brought heteropatriarchy and paternalism, dividing Indigenous men and women, and reducing women’s roles. Today, tourism and US military presence portray Okinawa as a feminized figure of paradise and Okinawan women as sexualized and infantilized.

Even activism in Okinawa has frequently embraced patriarchy, focusing on issues such as militarization over “women’s issues” (Tanji 2006, 2007). Today, Indigenous feminism invokes Unai (うない), an Indigenous Okinawan female god, to protect activists (Tanji 2006; Katsukata-Inafuku 2016). Okinawa: Women Act Against Military Violence (OWAAMV) applies the concept of Unai, stressing women’s and Indigenous Okinawans’ empowerment while networking transnationally with other feminist movements in militarized settings (Ginoza 2015).

References

Ginoza, Ayano. 2015. “Intersections: Dis/Articulation of Ethnic Minority and Indigeneity in the Decolonial Feminist and Independence Movements in Okinawa.” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 37, 13.

Katsukata-Inafuku, Keiko. 2016. “Creating an Okinawan Women’s Studies: Confronting Colonial Modernity with the Agency of “Unaiism.” Gender Studies 21: Waseda University Gender Research Center 6, 11-35.

Tanji, Miyume. 2006. “The Expansion of Women-Only Groups in the Community of Protest Against Violence and Militarism in Okinawa.” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context 13, 17.

———. 2007. Myth, Protest and Struggle in Okinawa. New York: Routledge.

Faith-centered Muslim feminists (whether western or west-based) are deeply engaged in contemporary feminist discourse. Through their scholarship and activism, Muslim feminists have not only traced the roots of women and gender in Islam, but they have also taken the initiative to reread and reinterpret the Qur’an. Islamic feminists dismiss the traditional interpretations of the Islamic texts, arguing that they are produced to serve both pre- and post-Islamic tribal traditions that are not supportive of women’s rights (Hamdan 2009). Muslim scholars like Leila Ahmed and Fatima Mernissi provide a new perspective on contemporary feminist debate about women in Islam by tracing the roots of women’s exploration of Islamic texts within historical and social contexts. Islamic feminists such as Asma Barlas and Amina Wadud offer a more liberatory interpretation of the Qur’an and Hadith (prophets’ sayings). For example, Wadud critically examines the gender notions of the Qur’an to address the sexist and bigoted image of Islam that has been produced by the traditional interpretation of Islamic texts (Haraway 1989; Majid 1998; Wadud 2006). The reinterpretation of the Qur’an from a woman’s perspective can create gender reform in the Muslim world, but only if such perspective is not secondary or supplementary to male social privilege or traditional ways of understanding knowledge (Wadud 2006).

Whether through a theoretical historicization or interpretative tradition, Muslim feminists have not only challenged the Orientalist and fundamentalist views of Muslim women, but they have also significantly contributed to contemporary feminist discourses and movements by developing a new form of political scholarship, feminism in Islam (Badran 2009). Like Islamic feminists, Muslim women have been proactively engaged in seeking social change from within subjugation through various and multiple means (Hamdan 2009).

The Black feminist movement emerged from the formation of the Black liberation movement and the women’s movement. The objective of the Black feminist movement was to establish ideas that could effectively resolve the interconnections of race, gender, and class. Many feminists affirm that Black women often faced prejudice in the feminist movement during the 1960s (Springer 2002). The Black feminist movement was founded in response to the discrimination and racism facing Black women in their campaigns, and it aimed to educate Black men and white women about the influence of racism on the lives of Black women (Smith 1985, 4-7).

What Is “Woke Culture”?

by Rebecca Lambert

What does it mean to be “woke”? The term has recently gained popularity, but where did it originate, and what does it really mean? As expressions gain mainstream popularity, their deep political roots are often erased from narrative and even co-opted and used in ways that do not relate to their original intent. The term woke has a long history based in African American Vernacular English (AAVE). Author William Melvin Kelley used the term in his 1962 essay in the New York Times titled “If You’re Woke You Dig It,” which talked about the co-optation of AAVE by white people.

Since then, the term has appeared in numerous outlets, from songs (such as “Master-Teacher,” recorded by Erykah Badu) to social movements. The term arose in Black culture and identifies a way of being in the world, a way of staying aware of the struggles and systems of oppression that the Black community has faced and continues to challenge. As woke became more mainstream, it started to be used more broadly, leading to an idea of a “woke culture,” a society that keeps the important political issues at the forefront of the public consciousness. As terms are rediscovered and incorporated into mainstream conversations, it is important to remember the cultural basis of language and speak accordingly.

The most noteworthy definitions of the Black feminist movement are Alice Walker’s description and the collective statement of Combahee River Collective. Alice Walker coined the term womanist and explained, “Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender” (Walker 2005, xii). The Combahee River Collective statement of 1974 was more politically focused and claimed that Black women’s liberation would mean equality for all people, as it would birth the end of racism, sexism, and class oppression. The development of integrated study and practice based on the intersections of the major structures of oppression is their unique mission (Combahee River Collective 2014).

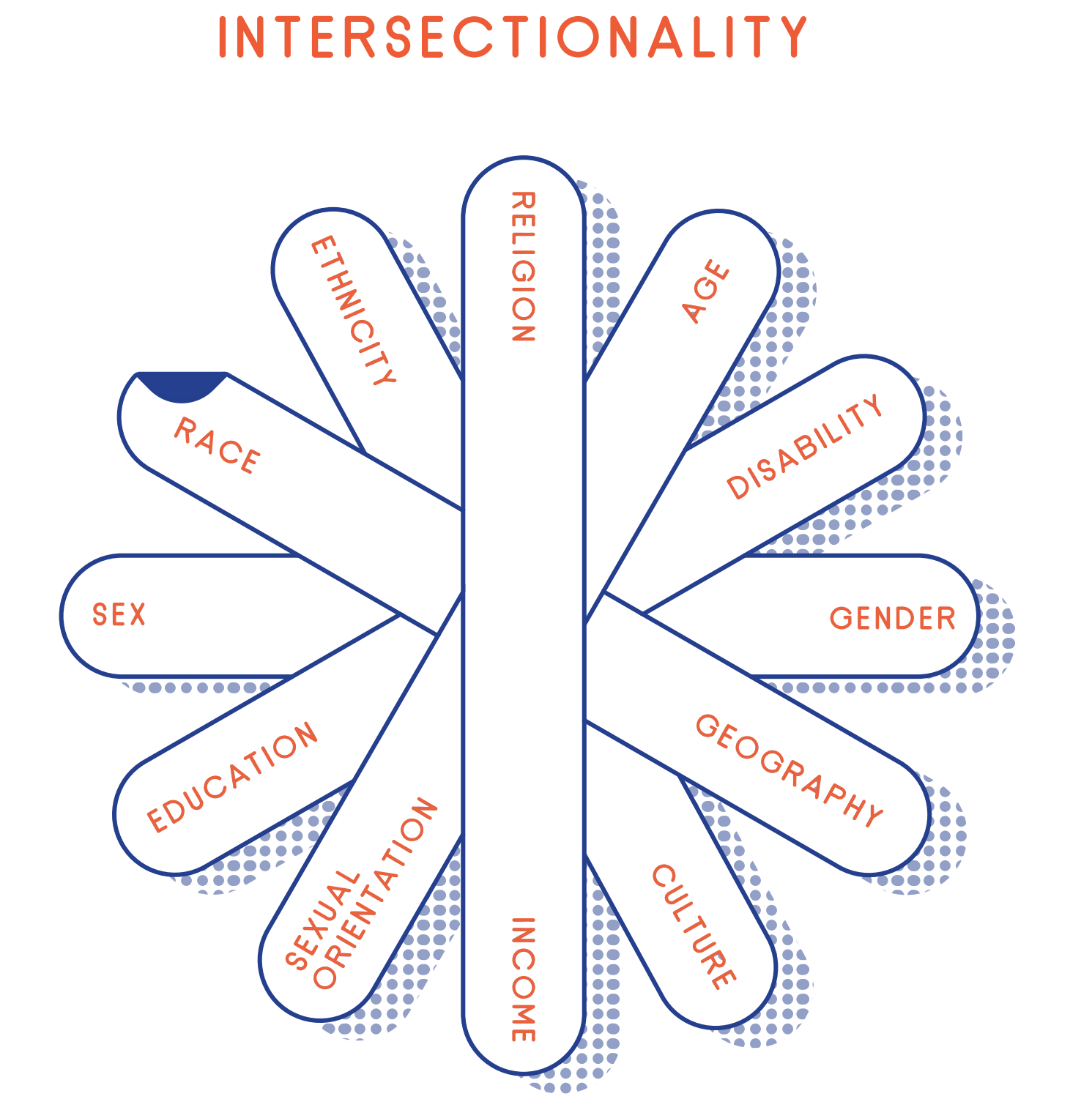

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a popular feminist law professor, termed the theory intersectionality when presenting identity politics (Crenshaw 1991, 43). According to Barbara Smith, the Black feminist movement since its emergence has focused on reproductive rights, discriminatory use of sterilization, fair access to abortion, health care, child abuse, rights of the disabled, women’s abuse, rape, sexual abuse, battering, welfare rights, lesbian and homosexual rights, aging, police brutality, labor organizing, the battle against imperialism, organizing antiracists, nuclear disarmament, and global warming (Smith 1985, 12).

Black feminism claims an inextricable connection between sexism, class inequality, racism, and all other forms of oppression (Davis 2011). Hence feminist theory now includes an analysis of how race, class, sexuality, and gender influence women’s lives (Smith 1985, 13).

Historically, in analyses of the contributions of African revolutionaries, the narrative has had a gender-specific focus, showcasing male personalities such as Nelson Mandela and a host of other African social movement activists, which has led to the marginalization of women in social and political conceptual frameworks. Therefore the role of revolutionary African women in social movements for women’s liberation, especially in countering mainstream narratives, must be discussed. African women played significant roles as revolutionaries before colonialism, after colonialism, and after independence. Lady Oyinkan Morenike Abayomi, for example, founded the Women’s Party in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1944 to campaign for women’s rights. Displeased with hyper-taxation without political representation, Lady Abayomi and the leaders of the party were crucial in campaigning for more educational and economic opportunities for women (Oyewumi 2004).

A rising percentage of women is coming together across Africa and making their voices heard, mobilizing across causes such as democracy, equality, reproductive health rights, and violence against women and girls. African feminists, scholars, and activists have made significant strides in their fight for equal political rights in their diverse countries, and women have been at the forefront of attempts to foster peace and reconciliation in other parts of Africa, such as Sierra Leone and Liberia. As most of these campaigns have been influenced by transnational feminism and transnational alliances, the contemporary global battle for women’s rights and liberation is increasingly being driven by female activists in Africa.

In 1951, activists Mabel Dove Danquah and Hannah Benka-Coker were pivotal in leading ten thousand people in a demonstration against rising food prices in Freetown, Sierra Leone. In 1954, Dove became the first woman to be elected to the legislature in West Africa. In the decades to follow, many women’s movements continued, as women across the African continent played crucial roles in twenty-first-century political and social movements.

In 1992, for example, the Social Democratic Front (SDF) of Cameroon of elderly women played a key role in catalyzing peace after the onslaught of post-electoral violence. Dr. Noerine Kaleeba founded the AIDS Support Organization Uganda (known as TASO Uganda) in 1997, which was the premier organization in Uganda to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In her quest to break down perceptions that define science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) research on the African continent as inferior, Nigerian scientist Tolu Oni is developing the Research Initiative for Cities Health and Equity (RICHE), an interdisciplinary research program that will tackle urban health disparities to find creative solutions and address complex public health issues.

While women activists such as Wangari Maathai, Winnie Mandela, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Albertina Sisulu are internationally renowned in their own right, and while scholars have done excellent work on the activism of African women, further work needs to be done to highlight the important contributions of African women to the building of social movements (Swift 2017). African women’s activism is not limited to carrying placards in street protests. Female activists, scholars, and feminists have begun to engage public and private institutions, using digital media sources to challenge systemic oppression and other forms of violence against women and girls.

In Nigeria, deep-rooted sociocultural and colonial problems have continued to dominate the views of society on who a woman is and her sense of being. Women’s rights are still a big issue facing Nigeria. Oyewumi affirms that African culture is replete with language that enables the community to diminish the humanity of women. She believes that African culture has a long history of discrimination and injustice toward women, as there has not been equity in opportunity, dignity, and power between men and women. She further states that various aspects of African culture prevent women from attaining equal status with men, such as limited access to education, rape culture, child marriage, female genital mutilation, sexual harassment at work, and all instances when a woman is restricted because of her gender, whether she is explicitly discriminated against under the law or simply unfairly treated or looked down upon (Oyewumi 1997).

The system of patriarchy, violence against women, the feminization of poverty and migration, globalization and the capitalist market system, and the practices of consumerism and commodification are still major issues for Nigerian feminists and activists. The general notion in Nigeria that women are inferior to men was recently reinforced when President Muhammadu Buhari, at a press conference in Germany, said the role of his wife, who is the First Lady of the Republic of Nigeria, did not extend beyond the kitchen and “the other room” (BBC News 2016). It was an unfortunate gaffe, especially given that women in Nigeria have made their mark in the political, educational, and economic fields. Nigerian women are thus subjected to various inequalities that have often led to women’s marginalization in politics, decision-making, and policy-making. An excerpt from We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie further affirms most Africans’ perception about feminism:

Why the word “feminist”? Why not just say you are a believer in human rights, or something like that? Because that would be dishonest. Feminism is, of course, part of human rights in general—but to choose to use the vague expression human rights is to deny the specific and particular problem of gender. It would be a way of pretending that it was not women who have, for centuries, been excluded. It would be a way of denying that the problem of gender targets women. That the problem was not about being human, but specifically about being a female human. For centuries, the world divided human beings into two groups and then proceeded to exclude and oppress one group. (Adichie 2014)

Two recent international cases have generated much hashtag activism: the #BringBackOurGirls in 2014 and the #EndSARS 2020 movements. Both movements were led by Aisha Yusuf, a Nigerian social and political activist who came to prominence for her role in speaking up for the 276 Chibok schoolgirls abducted by terrorists in 2014. She was also the co-convener of the Bring Back Our Girls campaign, which tirelessly held protests demanding the girls’ rescue. Although the hashtag started primarily to advocate for release of the girls, the emerging digital advocacy platform has also been used to challenge normative discourses on women and girl-children and violence within Nigeria. The movement was thus noted to be at the forefront of advocating social reform for women and girls by developing a counter-discourse that aims to foster gender equality and social justice for women and girls (Akpojivi 2020).

#EndSARS was not just a protest of police brutality (in the form of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, or SARS) but also, as Motolani Alake stated in Nigeria’s Pulse News, “a tone of rebellion, a note of valid belligerence, and a chant of unification in the Nigerian struggle against police brutality and terrible governance” (Warnes 2020). The #EndSARS movement was the tipping point after years of ongoing social trauma caused by inadequate health care systems and educational institutions, systemic corruption, nepotism, electoral fraud, poverty, and more. As an engaged feminist scholar, born and bred in Nigeria, I opined that the complaints about SARS are not new. Nigerian citizens have been speaking out online since 2017 and raising awareness about police brutality, with no successful attempts by activists to hold the government accountable.

The catalyst for the recent nationwide protests came in early October 2020, when reports surfaced in social media that police had attacked and killed a young man and driven off in his luxury vehicle. The movement to end police brutality was led by a couple of female activists and other young social media influencers, with initial demands for the notorious SARS police unit to be defunded and disbanded.

The protest has since morphed into a campaign for police reform and an end to bad governance in the oil-rich country. Soro Soke, meaning “speak up” in the Yoruba language of the region, was one of the common chants used during the protests. The significance of the chosen language was to be able to communicate and associate with the general masses and victims of institutionalized oppression. According to BBC News, Nigeria’s #EndSARS movement was much like the protests of police brutality in the United States by the Black Lives Matter movement. Nigerians in diaspora (those living in other countries) and other allies globally have stood in solidarity with the movement, which has attracted massive global support, shining a global spotlight on the #EndSARS hashtag (Khalid 2020).

Women played a leading role in powering the marches, and nearly $400,000 was raised by a large feminist coalition to fund the widespread marches that sprang up around the country and other countries where Nigerians reside. Several took to social media as a tool to engage bad governance in Nigeria. DJ Switch, an asylee in Canada, one of the young feminists present, played a significant role in leading the march and livestreaming the protests on her Instagram profile. On Black Tuesday, October 20, 2020, young protesters who sat and sang the national anthem were barricaded on either side of the Lekki toll gate in Lagos State, Nigeria, and were brutally massacred by Nigerian security forces (Busari 2020). DJ Switch was livestreaming the protests on her Instagram page when the shooting happened. She told CNN:

I’m heartbroken. There was no warning. We just heard gunshots and the soldiers came in guns blazing. It’s the worst thing I have seen in my life. They were just shooting like we were goats and chickens. (Busari 2020)

Despite the brutal massacre used to shut down the #EndSARS movement, feminists, activists, and Nigerian youths have continued to use all forms of media to challenge the patriarchal system of governance and build digital spaces for voices, interactions, and advocacy for social change. For the sake of those who died, leading to the protests and during the protests, the labor of our heroes’ past shall not be in vain. “The struggle must continue,” says DJ Switch. This challenge of systematic oppression by brave feminists and activists in Nigeria and elsewhere resulted in the disbanding of the SARS unit and led to the creation of judicial commissions by many jurisdictions around the country to investigate complaints against police officers. In addition, this social change movement has been instrumental in forming a strong coalition among several organizations fighting systemic oppression in Nigeria and across borders.

Feminist Organizing in Kazakhstan

by Shannon Garvin

In the wake of international criticism by human rights organizations on how peaceful protestors are attacked by police to disperse the crowds, feminists in Kazakhstan are finding their voice and experiencing a reprieve. On March 8, 2021, a Women’s Day march was observed by officials but allowed to proceed unhindered. About five hundred people attended, walking through the historic city of Almaty and listening to speakers address not only human rights issues that affect women but also those that address the needs of the handicapped and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, and intersex plus (LGBTQI+) communities. Domestic violence and disparity in access to economic resources have long plagued the vulnerable populations of the former Soviet Republic.

Veronica Fonova is a web designer who recently became a feminist activist and organized the country’s first official feminist rally. Organizers hoped to highlight chronic and systemic issues of discrimination and violence. The United Nations supports the work of local activists like Fonova and recently highlighted her work on its 25 Women—Generation Equality news page. Perspectives on the role of women and the level of patriarchy acceptable in a home and village vary greatly from the urban centers to the rural mountainous areas. Kazakhstan is a country in immense transition, as it has moved from an isolated Soviet Republic to an oil-rich nation selling its resources to the world in only twenty-five years. Veronica Fonova wants the future to be as rich and safe for its women and vulnerable people as it is for its men.

Listening to Our Activist Selves

The emergence of information and communication technologies, including the Internet, cell phones, and to some degree, radio and television, has facilitated the flow of information and created more regular and sustained communication between activists around the world (Moghadam 2012). These factors led to the potential of activists worldwide to transcend borders and to establish new platforms for discourse and mobilization across differences. Women have long organized across borders: several contemporary international women’s groups evolved from the middle to late nineteenth century in the form of suffragist, abolitionist, and anti-colonial movements (Moghadam 2015, 53-54). Globalization has created unprecedented opportunities for women and other oppressed groups to mobilize. Some scholars have argued that feminist and women’s advocacy groups were among the first to form transnational networks and have been some of the most effective (Desai 2007).

Transnational feminism is an approach to solving the limitations of global sisterhood by addressing differences between women’s struggles (Mohanty 2003). Transnational feminism is specifically committed to an intersectional approach to scholarship and activism, which includes critically addressing the ways in which connections between gender, race, class, sexuality, physical and mental capacity, and nationality are formed through locations and identities. Mohanty argues that transnational feminists focus on the struggle to form strategic coalitions (Mohanty 2003, 17-42).

The UN world conferences for women have been repeatedly highlighted by scholars as crucial to transnational feminist organizing. The conferences created a shared forum for women of various races, cultures, classes, and occupations from around the world to meet face-to-face, both formally and informally (Moghadam 2012, 417-20). These conferences were mostly renowned for fostering debates and dialogue between activists who challenged western women’s supremacy in framing the international women’s agenda. Scholars refer to the early conferences as contentious in nature (Linabary and Hamel 2015). Moghadam (2015) considered the 1985 Nairobi conference a turning point in these debates, when participants started making alliances and finding consensus on several key issues of concern. Young feminist activists are moving away from old mass media narratives of cultural and sexuality/gender politics and toward creating their own alternative narratives (Keller 2012). Harris, Wyn, and Younes (2010) argue that to date there has been insufficient feminist attention to women’s high take-up of web 2.0 technologies. Evidently, young activists share their experiences on digital platforms globally, build new ideas, and engage locally and globally to challenge everyday sexism, systemic oppression, and violence against women within and outside their geographical areas (Harris, Wyn, and Younes 2010).

It is important to engage and encourage the emergence and proliferation of transnational feminist networks, which provide fertile ground for activists across borders to create formal and informal networks around issues of interest. Furthermore, it is important that transnational feminist organizations, which exist at the intersections of various systems, actively discuss issues of privilege and exclusion while building new transnational alliances to create a better future for feminist activism globally (Hawkesworth 2018).

Conclusion

Transnational feminism pursues social justice by encouraging cross-border solidarity, decolonizing knowledge, honoring difference and diversity, and promoting equity transformations. Change commences with a process of self-assessment and criticism, in which differences are used to form an effective alliance around a common vision (Grewal and Kaplan, 1994; Mohanty 2003; McLaren 2017). As a decolonizing process of knowledge-building, transnational feminism brings together First World and Third World feminists for politically informed coalitions, wider acceptance, critical self-consciousness, greater impact, continued sustainability, and meaningful change for women worldwide.

Recognizing that there are differences among women’s varied visions, needs, priorities, interests, experiences, and historical contexts, transnational feminism challenges essentialist binaries such as North-South, First-Third, East-West, and male-female (Mohanty 2003; Lee and Shaw, 2011; hooks 2015). Creating and building on transnational activist coalitions, transnational feminists engage in renegotiating gender power relations; building cross-national alliances; and supporting women’s protests, movements, and cyber-activism to influence international laws and policies that affect women’s rights and status worldwide.

Women Who Rankle

by Janet Lockhart

In Stacy Schiff’s review of In Praise of Difficult Women, she says the author, Karen Karbo, describes the ways a woman can rankle others: “She can be independent, exacting, impatient, persistent, opinionated, angry, unaccommodating, ambitious, restless, confident, brilliant, articulate, or just plain visible.” (To rankle means to annoy, irritate, or cause resentment.)

Six women respond to this description:

Laureal: You can be yourself instead of who someone else wants or expects you to be. You “rankle” if you don’t meet the expectations others impose on you. Fuck that! That’s on them.

Andi: Oh! These words don’t just describe women but also the girls that they were! My parents worked very hard to raise an independent woman and were extremely pissed off (though also proud) by their success. To truly rankle, the woman simply has to be comfortable being themselves. I have compared sharing my world as similar to learning to water ski. Initially, the boat is way too fast. A person must hold on for dear life and hope that the driver knows how to navigate the waters; but if they hang in there, eventually it becomes fun. Although, some people just don’t like the waters.

Niki: The quote’s not wrong: women are perceived as difficult if they do any of those things. I don’t agree with it! I’m irritated that women are perceived that way, because they shouldn’t be. You take a woman who voices her opinion, she’s a bitch; but you take a man who has the same opinion, he’s listened to.

Shoshana: Being a “difficult” woman is often imbued with racialized connotations. Black, Jewish, Latina, and Indigenous women who speak out about injustice within institutions must navigate cultural stereotypes that intersect with their gender about being angry and uncooperative.

Dawn: These qualities were systematically driven out during my childhood—I’ve spent my adult life trying to embrace them without guilt.

Olivia: I love seeing women unapologetically acting as men traditionally would and claiming words such as “ambitious” and “unaccommodating.” Sometimes just their existence can cause others to be uncertain how to handle them. There’s something so beautiful about a woman that takes up space in an environment that doesn’t want her to.

Are you a woman who rankles? How do you feel about it? If you choose, how can you rankle more?

In the growing transnational and globalized world, and in the face of ongoing global gender injustice, transnational feminists skillfully use the Internet to build upon their resistance and foster their individual and collective quest for social transformation. Thus doing, these feminists translate their silence into a cyber-activist language for social change. Audre Lorde highlights the importance of speaking up as indispensable for social transformation. According to Lorde (1977), it is our silence, not our differences, that “immobilizes us.”

It is noteworthy that while feminists, activists, and other women have been tirelessly fighting for gender justice, rates of violence against women and girls are persisting or increasing globally. Feminists and women worldwide have been fighting multiple, concurrent battles—at the household, community, country, and transnational levels—experiencing backlash as they make gains toward gender justice, confirming the need for transnational feminism and activism more than ever.

Learning Activities

- Why is the “waves” model of feminist history problematic?

- What is transnational feminist activism? What strategies do transnational feminists use to create solidarity and enact change across borders?

- Review Afghan and Fletcher’s discussion of the #EndSARS protest of police brutality in Nigeria. Then take a few minutes to review #EndSARS online. What do you learn about #EndSARS from these sources? What can we learn about #EndSARS and the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States by considering them in relationship to one another? What can we learn about these movements by examining them through a transnational feminist lens?

- Take some time to review the UN Women website. In what way does the organization UN Women participate in transnational feminist activism?

- Define transnational feminism in your own words. Compare your answer to the answer to question 1 in chapter 1 in this volume.

- Working in a group, add these key terms to your glossary: feminist consciousness raising, cyber-activism.

References

Abu-Lughod, Lila. 2001. “Orientalism and Middle East Feminist Studies.” In Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives, edited by Carole R. McCann, Seung-kyung Kim, and Emek Ergun, 148-54. New York: Routledge.

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. 2014. “Excerpt from We Should All Be Feminists.” Feminist.com. Accessed November 2020. https://www.feminist.com/resources/artspeech/genwom/adichie.html.

Afshar, Haleh. 1998. Islam and Feminisms: An Iranian Case-Study. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Akpojivi, Ufuoma. 2020. “I Won’t Be Silent Anymore: Hashtag Activism in Nigeria.” Communication: South African Journal for Communication Theory and Research 45, no. 4, 19-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02500167.2019.1700292.

Badran, Margot. 2009. Feminism in Islam: Secular and Religious Convergences. Oxford: Oneworld.

BBC News. 2016. “Nigeria’s President Buhari: My Wife Belongs in Kitchen.” October 14, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37659863.

———. 2017. “Egyptian TV Presenter Sentenced over Pregnancy Remarks.” November 2, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41849838.

Brown, Elsa Barkley. 1992. “‘What Has Happened Here’: The Politics of Difference in Women’s History and Feminist Politics.” Feminist Studies 18, no. 2, 295–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178230.

Busari, Stephanie. 2020. “Nigeria’s Youth Finds Its Voice with the EndSARS Protest Movement.” CNN World News. October 25, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/25/africa/nigeria-end-sars-protests-analysis-intl/.

Combahee River Collective. 2014. “A Black Feminist Statement.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 42, no. 3/4, 271-80. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24365010.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6, 1241-99. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

Davis, Angela. 2002. “Working Women, Black Women and the History of the Suffrage Movement.” In A Transdisciplinary Introduction to Women’s Studies, edited by Arlene Voski Avakian, and Alexandrina Deschamps, 73-78. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

———. 2011. Women, Race and Class. New York: Vintage.

Desai, Manisha. 2005. “Transnationalism: The Face of Feminist Politics post‐Beijing.” International Social Science Journal 57, no. 184, 319-30. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2005.553.x.

———. 2007. “The Messy Relationship between Feminisms and Globalizations.” Gender and Society 21, no. 6, 797–803. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277786440_The_Messy_Relationship_Between_Feminisms_and_Globalizations.

Grewal, Inderpal, and Caren Kaplan, eds. 1994. Scattered Hegemonies: Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hamdan, Amin. 2009. Muslim Women Speak: A Tapestry of Lives and Dreams. Toronto: Women’s Press.

Haraway, Donna. 1989. Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. New York: Routledge.

Harris, Anita, Johanna Wyn, and Salem Younes. 2010. “Beyond Apathetic or Activist Youth: ‘Ordinary’ Young People and Contemporary Forms of Participation.” Young Nordic Journal of Youth Research 181, no. 1, 9-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/110330880901800103.

Hawkesworth, Mary E. 2018. Globalization and Feminist Activism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene Nagy, and Patricia Lina Leavy. 2007. Feminist Research Practice: A Primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abigail_Brooks/publication/309282474_Feminist_Standpoint_Epistemology_Building_Knowledge_and_Empowerment_Through_Women’s_Lived_Experience/links/5807782008ae63c48fec548e/Feminist-Standpoint-Epistemology-Building-Knowledge-and-Empowerment-Through-Womens-Lived-Experience.pdf.

hooks, bell. 2015. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. New York: Routledge.

Ismail, Manal, and Maysam Ali. 2008. “Women Enter the World of Media.” GulfNews.com. March 9, 2008. https://gulfnews.com/general/women-enter-the-world-of-media-1.90585.

Keller, Jessalynn Marie. 2012. “Virtual Feminisms: Girls’ Blogging Communities, Feminist Activism, and Participatory Politics.” Information, Communication and Society 15, no. 3, 429-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.642890.

Khalid, Ishaq. 2020. “No Justice for End Sars Protest Victims-Rights Groups.” BBC News. October 20, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/topics/cezwd6k5k6vt/endsars-protests.

Lee, Janet, and Susan Shaw. 2011. Women Worldwide: Transnational Feminist Perspectives on Women. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Linabary, Jasmine R., and Stephanie A. Hamel. 2015. “At the Heart of Feminist Transnational Organizing: Exploring Postcolonial Reflexivity in Organizational Practice at World Pulse.” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 8, no. 3, 237–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2015.1057909.

Lorde, Audre. 1977. “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 40-44. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007.

Majid, Anouar. 1998. “The Politics of Feminism in Islam.” Signs 23, no. 2, 321-61. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3175093.

McLaren, Margaret A. 2017. Decolonizing Feminism: Transnational Feminism and Globalization. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Mernissi, Fatema. 2004. “The Satellite, the Prince, and Scheherazade: The Rise of Women as Communicators in Digital Islam.” Transnational Broadcasting Studies 12, 12.

Moghadam, Valentine M. 2005. Globalizing Women: Transnational Feminist Networks. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

———. 2012. “Global Social Movements and Transnational Advocacy.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Political Sociology, edited by Edwin Amenta, Kate Nash, and Alan Scott, 408–20. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

———. 2015. “Transnational Feminist Activism and Movement Building.” In The Oxford Handbook of Transnational Feminist Movements, edited by Rawwida Baksh and Wendy Harcourt, 53-81. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mohanty, Chandra. 1988. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Feminist Review 30, no. 1, 61-88. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.1988.42.

———. 2003. Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Naples, Nancy. 2009. “Crossing Borders: Community Activism, Globalization, and Social Justice.” Social Problems 56, no. 1, 2-20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/sp.2009.56.1.2

Narayan, Uma. 1997. Dislocating Cultures: Identities, Traditions, and Third-World Feminism. New York: Routledge.

Nouraie-Simone, Fereshteh. 2005. On Shifting Ground: Muslim Women in the Global Era. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York.

Oyewumi, Oyeronke. 1997. The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

———. 2004. “Conceptualizing Gender: Eurocentric Foundations of Feminist Concepts and the Challenge of African Epistemologies.” In African Gender Scholarship: Concepts, Methodologies, and Paradigms. Dakar, Senegal: Codesria.

Radsch, Courtney. 2012. “Unveiling the Revolutionaries: Cyberactivism and the Role of Women in the Arab Uprisings.” James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University. May 17, 2012. https://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/91851/ITP-pub-CyberactivismAndWomen-051712.pdf.

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Smith, Barbara. 1985. “Some Home Truths on the Contemporary Black Feminist Movement.” Black Scholar 16, no. 2, 4-13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41067153.

Somolu, Oreoluwa. 2007. “Telling Our Own Stories: African Women Blogging for Social Change.” Gender and Development 15, no. 3, 477-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070701630640.

Springer, Kimberly. 2002. “Third Wave Black Feminism?” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 27, no. 4, 1059-82.

Staggenborg, Suzanne, and Verta Taylor. 2005. “Whatever Happened to the Women’s Movement?” Mobilization: An International Journal 10, no. 1, 38-52. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263536175_Whatever_Happened_to_The_Women%27s_Movement.

Swift, Jaimee A. 2017. “African Women and Social Movements in Africa.” Black Perspectives. July 18, 2017. https://www.aaihs.org/african-women-and-social-movements-in-africa/.

Wadud, Amina. 2006. Inside the Gender Jihad: Women’s Reform in Islam. Oxford: Oneworld.

Walker, Alice. 2005 [1983]. In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. London: Phoenix.

Warnes, William. 2020. “A Struggle against Brutality: Nigeria’s #EndSars Movement.” Concrete. March 11, 2020. https://www.concrete-online.co.uk/a-struggle-against-brutality-nigerias-endsars-movement/.

Yang, Guobin. 2016. “Narrative Agency in Hashtag Activism: The Case of #BlackLivesMatter.” Media and Communication 4, no. 4, 13-17. https://www.cogitatiopress.com/mediaandcommunication/article/view/692/692.

Image Attributions

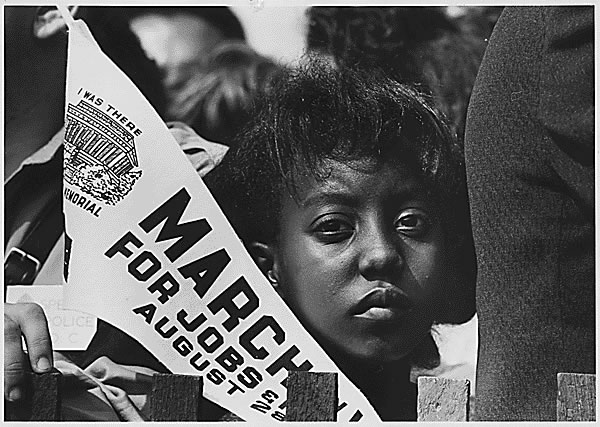

14.1 “Public Domain: 1963 March on Washington by USIA photographer, 1963 (NARA)” by pingnews.com is in the public domain

14.2 ““I wish you’d admit that you harass”, “I wish I could feel safe in the streets.”” by UN Women Arab States is available under CC PDM 1.0

14.3 “Intersectionality” by OSU OERU is licensed under CC BY 4.0

14.4 “Sign at a 16 October women’s empowerment rally in Nigeria” by Africa Renewal is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

14.5 File:Abuja, Nigeria Oct 12, 2020 01-28-13 pm.jpeg by Aliyu Dahiru Aliyu is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

14.6 File:Oslo Women’s March IMG 4244 (24948017197).jpg by GGAADD is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

14.s6.1 “PussyHats” by adrianmichaelphotography is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Secular and Islamic feminisms are two different schools of thought. While secular feminism centers on promoting gender equality in both private and public arenas, Islamic feminism seeks social change through using religion, especially by reinterpreting the Qur’an, to demand gender equality. Despite their different approaches, both schools together constitute “feminism in Islam” (see Badran 2009). ↵