6 Teaching Social Justice Themes Online

Deanna Lloyd and Jenny N. Myers

Introduction

The inclusive course design and teaching strategies outlined in previous chapters lay the groundwork for changes to online pedagogy that strive toward inclusive excellence. In this chapter, we expand on these foundations in the context of courses designed to address social justice content specifically. Bell (2016) offers a useful overview of social justice education (SJE):

The goal of social justice education is to enable individuals to develop the critical analytical tools necessary to understand the structural features of oppression and their own socialization within oppressive systems. Social justice education aims to help participants develop awareness, knowledge, and processes to examine issues of justice/injustice in their personal lives, communities, institutions, and the broader society. It also aims to connect analysis to action; to help participants develop a sense of agency and commitment, as well as skills and tools, for working with others to interrupt and change oppressive patterns and behaviors in themselves and in the institutions and communities of which they are a part. (4)

As Bell describes, social justice education is about more than just helping students gain awareness and understanding of social systems; it also supports students in reflecting and interrogating their personal connections to and complicity in unjust systems, and supports learning to act in ways that promote justice and equity. In order to facilitate transformative learning in online SJE classrooms, we feel it is critical to interrogate the systems and roles we operate within. Social justice education is not just about pedagogical transformation; it also calls for systemic and structural changes within institutions of higher education. As such, before we discuss specific considerations related to inclusive pedagogy in online SJE classes, we briefly examine some of the systems, assumptions, and tensions influencing online teaching and learning.

Western higher education institutions were founded on—and continue to be enmeshed within—colonial societies, systems, and values (Grosfoguel 2013). As Stein et al. (2021) write, Like all institutions in colonial societies, institutions of higher education are entangled with systemic, historical, and ongoing colonial violence and ecologically unsustainable systems; their funding streams, real estate, political legitimacy, epistemic authority, and social relevance are all dependent on the continuity of this violence

(13). Furthermore, online learning is reliant on technologies (e.g., computers, the Internet, learning software) that have been developed within the context of capitalistic, extractive systems (Myers 2021). As Watters (2018) notes, Educational technologies are embedded in educational institutions; they’re entwined with the histories and practices of schooling. Even the technologies that are imagined to ‘disrupt’ institutions and revolutionize teaching and learning are inescapably bound to cultural expectations

(xii).

It is important to acknowledge the risks of cultural homogenization that online learning can facilitate and consider ways to decolonize our online teaching practices. As Samuel (2024) writes,

Decolonization of online learning involves recognizing the constraints imposed by the colonizer, disrupting these constraints, and embracing alternatives . . . This includes decentering the Western, Eurocentric voice, incorporating diverse indigenous perspectives, and providing options and alternatives to minimize the privileging of English and Western knowledge. Embracing alternatives also involves utilizing technology to minimize linguistic barriers and provide educational opportunities that carry global currency while also valuing and incorporating local knowledge and curriculum. (439)

Inclusion efforts are one part of the process of decolonizing academic spaces. They can reduce acute colonial harm and create opportunities for Indigenous students and others traditionally marginalized in academic settings. Yet inclusion efforts alone do not do enough to counter colonization. In fact, reliance solely on inclusion to address systemic harms risks perpetuating the idea that the primary wrong of colonization [is] the exclusion of Indigenous peoples from supposedly universal mainstream institutions, knowledges, and sensibilities

(Stein et al. 2021, 20) without addressing the ways higher education institutions benefit from the dispossession of Indigenous lands and perpetuate cultural erasure. Indeed, inclusion efforts may only further fortify colonization by giving it a kinder, gentler facade

(Stein et al. 2021, 20).

As individual instructors, we likely have the most influence over the structure and facilitation of our classes, and inclusive practices can make a significant difference to our students and their learning. If inclusion efforts were wholly harmful, we would not be promoting them through our writing, but we do think it is pivotal to consider their limitations. We bring up this tension not to discount inclusion efforts or cause decision paralysis, but to highlight a systemic challenge to teaching and achieving social justice in higher education and how inclusive practices are one important tool but not a systemic solution. What we offer below are considerations related to inclusive pedagogy with the acknowledgment that they come with limitations since they are offered within oppressive societal systems and address symptoms rather than the systemic root causes of inequity and injustice. For resources to support academic decolonization and other forms of systemic change beyond the online classroom, see, for example, Machado de Oliveira (2021), Stein et al. (2021), and Joseph-Salisbury and Connelly (2021).

Contextualizing Our Perspectives

As noted in the introduction to this text, part of the original impetus in motivating OSU to develop the Inclusive Teaching Online (ITO) workshop came from feedback from instructors new to teaching social justice courses. Instructors and graduate students who inherited courses designed by other instructors approached Ecampus staff with requests to remove assignments in online courses that required careful facilitation, particularly in discussion boards. Ecampus recognized a need for instructor training in facilitating complex conversations online related to critical themes in social justice education like systemic racism and white supremacy.

Those of us teaching classes with SJE learning outcomes are likely integrating material and activities that help our students work toward the multiple goals and attributes identified in Bell’s (2016) SJE definition. For other instructors, social justice education may not be central to their course, but there may be opportunities to incorporate social justice themes in other disciplines. For example, an agriculture class might include a module on farmworker rights that can be used to explore social justice themes such as equity, economic justice, racism, access to social support structures, activism, and so on. This chapter does not dive into the nuance and complexity of teaching SJE, as there are many resources on that topic (see Osei-Kofi et al. 2021 or Adams et al. 2022). Rather, our focus in this chapter is primarily on how shifts in design and facilitation within online SJE classes can promote more inclusive education.

This chapter was written by two white, cisgender female faculty members who have taught social justice courses in the Sustainability Double Degree program at OSU. We have both participated in faculty development opportunities in this area, and we share insights from our experiences designing and teaching courses, including Social Dimensions of Sustainability; Power, Privilege, and the Environment; Sustainability, Justice, and Engagement; and Identity and Belonging in the Outdoors.

In addition to our perspectives, this chapter includes the voices of instructors who completed the ITO workshop and who teach SJE courses. We conducted in-depth narrative interviews where participants reflected on their strategies, ongoing challenges, and success teaching courses in the fields of history; education; women, gender, and sexuality; and natural resource management. Participants included graduate students and non–tenure track teaching faculty at various stages of their careers with different levels of power and control over their course design, content, and class size. The instructors we interviewed consistently noted that, through ongoing reflection and adjustments in course design, they have developed techniques to foster meaningful relationships with students, facilitate peer-to-peer learning, and navigate the unique challenges online classrooms pose in facilitating SJE courses. Their insights are integrated into the considerations highlighted below.

We frame the discussion below not as “strategies” but rather as “considerations.” This language choice is deliberate, as we want to avoid prescriptions and abstain from making assumptions of universal relevance because we recognize there is partiality, plurality, and provisionality in knowledge (Russell 2010). We hope the considerations offered encourage problematization and critical engagement with the ideas presented here.

Considerations for Online SJE Course Design and Facilitation

Instructors who are already teaching SJE courses online will know that the modality raises a special set of considerations, namely stemming from the lack of synchronous interaction where student responses have physical cues and the instructor can immediately intervene if students need support. If you are new to teaching SJE course online, or if you are considering weaving in social justice content into your online course, there are a number of factors to consider and plan for:

- How will you present yourself to students in relation to the course subject matter? What additional implications are there for revealing or not revealing aspects of your own identities and positionalities?

- How will you build rapport with your students and cultivate a safe environment to explore complex societal challenges without face-to-face interactions?

- How will you support students as they encounter material that they find threatening to their worldviews or psychologically triggering?

- How will you leverage and value students’ lived experiences as an intentional part of the course experience?

There are no easy answers to these questions, in large part because they are both contextual and personal. It may be reassuring to hear that instructors who have taught SJE courses online continue to grapple with these questions and routinely adjust their approaches. This chapter can function as a useful primer for instructors who may not have taught social justice themes or courses online yet but are considering doing so. The ideas in this chapter may also serve instructors who teach online social justice courses and who are looking to reflect on their course facilitation. We hope these considerations will be supportive for instructors wishing to expand their confidence addressing social justice themes, regardless of disciplinary locations.

Building Classroom Community

This section offers considerations related to the cultivation of the online classroom and community, with particular focus on both student–student and student–instructor dynamics.

Cultivate Community and Foster a Safe Space to Explore Complex Issues

Course design that supports community-building is an essential facet of online SJE courses. As discussed in chapter 4, online communication can feel impersonal and lead to a lack of social presence—the sense that one is interacting with real people and is connected to others (Kear et al. 2014; He 2022). As noted previously, the heavy reliance on written communication in online courses makes it difficult to interpret context cues without body language to aid in expressing meaning and tone. Instructors may not feel confident assessing students’ reactions to information when they cannot see physical cues such as folding arms, showing rapt attention, fidgeting, looking away, leaning into the conversation, and so on. For some students, a lack of social presence and connection to other students in an online SJE classroom may prevent them from feeling comfortable enough to share their perspectives and lived experiences. In contrast, students who are less comfortable speaking in front of people or who take more time to process information often prefer asynchronous, online discussions that allow more time to reflect and write out their contributions. With students having a spectrum of preferences, consider how the lack of real-time information about how students are processing complex course content can impact approaches to the course design itself.

An instructor who transitioned an on-campus course about intimate partner violence reflected on the importance of community- and relationship-building in the online classroom because of the different experiences and perspectives students bring to the course:

The topic is so intense. We get a lot of survivors coming through the class. We occasionally get somebody who’s really antagonistic that comes through the class. It’s really intense emotionally for folks. I was really worried about my ability . . . to develop a classroom environment in which students felt safe enough that they could process the information. . . . I feel like I did a pretty good job of that on campus. . . . But it’s been a really positive experience [online]. And in some ways you end up connecting with students a lot more.

Creating the sense of safety required to discuss social justice issues is essential, particularly when topics touch students’ lives in a personal way. Community-building in an online course can take many forms. Instructor-to-student communication is an opportunity to model your hopes for what engagement in the course can look like. As discussed in chapter 3, many instructors start developing instructor presence with an introductory video that sets the tone for the course. Using a variety of communication strategies—writing weekly announcements, providing personalized feedback on student work, and participating in discussions—demonstrates to students that you are actively engaged and invested in their learning journeys. Consider using video or audio recordings for weekly announcements and feedback on assignments, so students can see you and hear your voice to personalize their learning experience.

Student-to-student interactions can also provide an opportunity to build a sense of safety in online SJE classrooms. These interactions can take place in peer-reviewed assignments, small group discussions, or full class discussions. We recommend having students post introductory videos about themselves at the beginning of the term, with flexibility to submit voice-over or audio-only contributions for students who prefer not to be on camera. These introductions foster social presence in peer cohorts and provide instructors insights about students’ lives and learning needs. Consider having students interact with the same small discussion groups for all or part of the term so that they can build relationships as the term progresses.

Interrogate Power Dynamics within the Classroom and Institution

Social justice education interrogates systems of power and oppression, and yet higher education is a space where power structures and oppressive systems are easily reproduced. In online courses, instructors have opportunities to shift power dynamics in ways that are hard to achieve in in-person classrooms, where they are often physically stationed standing in front of a seated audience. In online courses, absent these physical cues, we can reorient the power dynamics in the virtual room. Inviting students to contribute to class decisions about class norms, assessment choices, class structure, or course topics can demonstrate power sharing and shift from instructor-centered learning to student-centered learning (Considine et al. 2017; Hanesworth et al. 2019). Integrating these types of emergent practices into an online classroom, though, can be a challenge since online content is often created and launched prior to the start of class. Instructors can work with instructional designers to create a flexible structure for content designed with students. One possible way to integrate this flexibility is to create a course template that includes placeholders for select learning materials and/or activity prompts and allows the instructor time to co-construct those subsequent learning experiences with students.

Another avenue for disrupting power dynamics is for instructors to offer transparency about their own learning and reflexive processes. This can humanize the instructor as someone who is also on a learning journey and is fallible rather than an unapproachable “expert.” As discussed in chapters 1 and 4, deciding what to share is a personal decision for each instructor, and that decision may change depending upon the course. Some instructors may decide to share information about their personal or professional experiences and what biases they present related to course content. We can also acknowledge when we learn something new from a student, model vulnerability (described in more detail later in the chapter), or reflect deeply about the societal narratives we are grappling with ourselves.

Collaboratively Create and Clearly Communicate Class Expectations

With the wide range of lived experiences, perspectives, and social messaging that students and instructors bring into a social justice classroom, creating a list of group norms for respectful interaction and dialogue and asking students to agree to them can be helpful in creating a constructive learning space that recognizes complexity, power dynamics, and complicity (Bell 2016). At the beginning of the term, collaboratively creating group norms can be a way to demonstrate your commitment to sharing power in the course; encourage students to consider the distinctions between discussions, debates, and dialogues (see chap. 5); and foster student buy-in.

With the asynchronous nature of the online classroom, it can be challenging to facilitate a collaborative process to generate group norms from scratch and revise them asynchronously, ensuring everyone’s voices are reflected in the final product. In our teaching practices, we often ask students to read examples and suggest their own group norms for the class in a discussion board. Another option is to propose a list of norms, ask students to review and reflect on them, and have students share if there are other points they feel are missing or important to clarify. For example, if using preconceived Group Norms for Dialogue, such as those listed in the highlighted text box, students could engage with those norms by being asked to reflect upon a point from the list that resonates with them and a point they feel may be a challenge or brings up further questions and concerns. If doing this in a group or discussion board format, students can see that their peers are also critically considering the norms and may share some of their same concerns.

Group Norms for Dialogue

By Brandi Douglas and Jeff Kenney, Oregon State University,

and adapted from Ruby Beal, University of Michigan

True dialogue is achieved when its participants have a certain mindset. The following norms will help us develop that mindset as a group:

- We recognize that our primary commitment is to learn from each other and from our experience. We acknowledge differences amongst us in skills, interests, values, scholarly orientations, and experience.

- We acknowledge that racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, ableism, and other forms of discrimination (religion, age, language, etc.) exist and may surface from time to time.

- We will do our best to not blame people for the misinformation we have learned, but we hold each other responsible for repeating misinformation or offensive behavior after we have learned otherwise.

- We will trust that people are always doing the best they can, both to learn from others and to behave in productive ways.

Dialogue also calls for certain actions from its participants. These norms describe the actions that make dialogue possible:

- We will listen actively to one another. We acknowledge that everyone has an equal, valid voice in our dialogue.

- We will actively pursue opportunities to learn about our own groups and those of others, yet not enter or invade others’ privacy when unwanted.

- We will all strive to create a safer atmosphere for open dialogue. We will honor the confidentiality of others in the group and be conscious of our nonverbal communication.

- We will challenge the idea and not the person.

- We recognize that dialogue is not always comfortable. We will speak our discomfort and allow space for others to do the same.

Alongside guidelines for respectful interactions, it can be helpful to remind students that, depending on the activity, their physical environment can also become part of the class. For example, with assignments where students have the requirement or option to record video responses to question prompts or discussion posts, the space where the student records their video becomes part of the learning environment. Including guidelines about video etiquette in your syllabus and in assignment instructions can help ensure that images shared in the classroom environment foster a safe and productive learning environment. Students can be prompted to look behind and around themselves to notice whether there are posters or other visuals on their walls that are inappropriate for a college classroom before they hit the record button. Encouraging the use of a neutral location to record, using a background template/image, or blurring their background are all good suggestions.

Engage Students’ Lived Experiences

As discussed in chapter 2, the student population that online courses tend to serve is often older, with more firsthand knowledge to examine through a social justice lens. Instructors noted in interviews that this was a benefit. One observed, “A lot of my students have life experience that they’re bringing to the classroom. They’re in the workforce. Or they’ve been working for a while, and they’re coming back to school later in life. They bring all this experience to these online discussions, which makes it so rich.”

Discussions and other student-to-student engagement can be broadened by the depth and variety of lived experiences that students share about through these activities. Depending on the class context, there are many ways to support students in reflecting on, connecting to, and potentially sharing about their lived experiences. Scavenger hunts, either completed in person or through Internet research, are an example of an activity that can get students to think more deeply about their community experience, reflect on course topics, and dialogue with peers. For example, students could catalogue natural spaces and parks in their communities to discuss inequities in access to green spaces. Online, they could research census data to consider educational disparities. Other place-based activities such as environmental autobiographies, mapping exercises, or interviews with community members encourage students to connect with the learning material and build community in the classroom as they share personal examples with their peers (see also da Silva et al. 2024).

Another instructor we spoke with noted that there is a misperception among instructional faculty that students enroll in online classes because they think they are easier, exposing a bias that online students are less serious or motivated (as discussed in chap. 2). They reflected on their own perception shift, realizing that online students choose particular social justice–themed courses—not simply to fulfill the degree requirement—but because they care about the topic or want to learn theory to contextualize their own experiences. The instructor observed:

E-campus students often care more, and there’s a misperception that they care less. . . . They’re very intentional with the way that they’re structuring their program and the classes that they’re signing up for. When establishing rapport, and not just between me and students, but among the students . . . I think I struggled with that a little bit when I first started. But then I realized, “Oh, E-campus students really care.” And for some of them, in fact, this is their core sociality. This is where they get most of their peer interaction, especially with people who are interested in similar topics. And I think for me, a really important consideration with DPD is [that] . . . some students are signing up because [the course addresses] part of their identity, or part of their experience.

Even with the wider array of identities typically present in the online classroom, the relative anonymity of the online space may prevent students from recognizing the different identities of their peers (Dumford and Miller 2018). Cultivating a supportive classroom that honors a diversity of experiences and identities can help students feel more confident in their learning and comfortable sharing about their lived experiences. Fostering discussions and assignments that invite students to bring their whole selves to online social justice conversations requires a careful cultivation of a classroom community. There is no best way to ask students to share because each classroom, student, and context is unique, and there is more risk involved for some people than others.

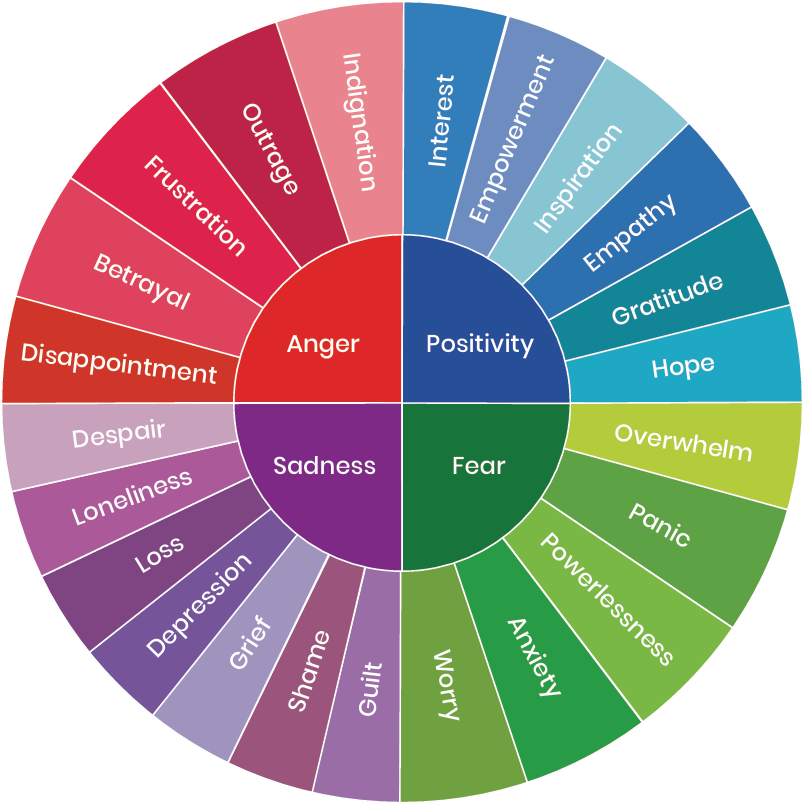

Examples to increase personal engagement could include asking students to reflect on how their lives have been affected by climate change; encouraging students to reflect on their understanding and experiences through a scavenger hunt centered around their own community; or inviting students to use a color wheel of emotions to identify how they feel about certain class topics or material (see fig. 6.1 or this Emotional Word Wheel). Integrating students’ lived experiences with care into the classroom and activities can deepen learning and help students build relationships with peers across differences, thus increasing empathy and multicultural literacy. As Phirangee and Foster (2024) note, Fostering a sense of community within online courses empowers students to engage in discussions, share insights, and connect with diverse knowledge sources beyond the instructor’s expertise. Such collaboration not only facilitates the exposure to varied perspectives but also encourages students to challenge their own biases and construct new knowledge

(35).

Model Vulnerability

Depending on the course and how the instructor facilitates it, self-reflection, vulnerability, and humility may play a key role in the learning process, material, and activities. Sharing power and vulnerability with students can be a way to shift from one-way, didactic exchange of information to a more democratic, two-way form of sharing information that models collaborative learning and growth. In the online classroom, some ways to support these behaviors could include the creating and sharing of videos that demonstrate an instructor’s own processing and self-reflexivity about the topics; instructor transparency about their thought process and design of the course; or sharing stories about relevant learning moments or lived experiences.

There is a risk that these types of materials could appear to center the instructor’s experience, but with thoughtful and intentional framing and use, they can be powerful tools that model growth, learning, and reflexivity to your students. For example, in Deanna’s Sustainability, Justice, and Engagement class, when covering information on implicit bias, she asks students to reflect on a personal experience with implicit bias and how they might approach the situation differently based on what they have learned in class. She could just ask students to be vulnerable and share their reflections to various prompts, but that would keep all the power with her. Instead, Deanna recognizes her positionality as the instructor and decides to expose her own vulnerability and fallibility through a video reflection about two different times when she made mistakes with language about social justice issues and how she was called upon to be accountable for those mistakes. She then discloses how she felt as she processed the situation and analyzes her responses to the situations. It has been powerful for Deanna to see how students have engaged and reacted to her vulnerability in primarily positive ways. As one student shared, Hearing about your experiences felt authentic, supportive and showed us how it is possible to lead by example. Also, I felt hopeful in that I can learn from my mistakes and continue to grow and evolve.

While modeling vulnerability has worked well for Deanna, who is white and cisgender, as with the sharing of identities, different people will have different levels of risk when incorporating strategies that decenter the instructor as expert, share power, or model vulnerability to students. These strategies can challenge student perceptions of authority and expectations of professionalism, which can lead to either student growth or resistance. With tenure and promotion processes tied to student evaluations, stretching student perceptions with these types of strategies can have significant consequences, particularly for instructors of color and women (see chap. 3). This highlights the important fact that although certain strategies can work well for some, there are no universal best practices. Our teaching is contextual and dynamic and how we interrogate power with our students will look different depending on our specific contexts.

Let Students Know Who Will Read Their Submissions

It can be helpful for students to know who will be in their discussion groups and when an assignment will be viewed by classmates versus just the instructor. As noted above, students come to SJE courses with different levels of understanding and comfort with the subject material. Some may come with a lifetime of personal experience with the course topic. As such, they may share more openly in assignments read only by the instructor, or they may find community support sharing their perspectives with select peers. In one example from an instructor we interviewed, survivors of domestic violence were willing to reflect deeply about their experiences in personal journal assignments read only by the instructor. Yet in another instructor example, students were more reserved in assignments focusing on themes relating to the perceived racial identity of their instructor.

Because our teaching and learning is contextual, the benefits and drawbacks to having students share with their peers versus the instructor will vary depending on the students, course content, classroom cultural context, disclosed and perceived instructor identities, and the like. Instructors can prepare students by including a “Who’s Here?” statement at the top of each discussion and assignment to build a sense of safety in the classroom and allow students to choose how they show up. Students will benefit from spaces where they do not have to be concerned about potential judgment from peers. But in a classroom environment that fosters a challenge by choice ethos, students can grow when they share their experiences, recognize congruence between their personal experience and that of others, and learn from one another (which connects to the frameworks that support learning through social interaction discussed in chap. 1). Providing students the opportunity to think critically about their comfort level engaging with different audiences encourages community-building in the classroom; models clear communication; and provides scaffolding to support students’ various needs, experiences, and identities.

Encourage Students to Pause and Reflect before Responding

A key advantage to teaching SJE courses online is that there is no pressure to respond to complex ideas in the heat of the moment. When students are triggered by the material, or their defenses are raised, asynchronous discussion assignments with staggered deadlines for initial posts and peer replies give students more time to process information and perspectives shared by their classmates. Encouraging students to pause and reflect before responding to discussion boards is of particular benefit in social justice classrooms, where students may be even more wary of sharing their perspectives because of fears about “messing up” and offending people or appearing ignorant about other cultures. These fears can be mitigated by discussion prompts that remind students to take their time, do further research on an idea or perspective, and craft their responses when they are emotionally regulated.

Pause and Reflect before Responding

Just as students benefit from the increased processing and response time afforded by asynchronous modality, so too do instructors. While a prompt response in an online space may still be necessary to avoid a discussion spiraling unproductively, online instructors often have more time to contemplate how to respond in ways that defuse tension and are supportive of learning. It is best to do this when we are emotionally regulated to avoid reactive responses that lack depth and explanation, that read as defensive or dismissive, that do not thoroughly address the problematic statement, or that perpetuate harm. With an online space, instructors also have the opportunity to share links or resources to further support student learning. As discussed in chapter 5, the listen, affirm, respond, and add information (LARA) method can be a useful framework to consider when responding to students.

Reach Out to Disengaged Students

In chapter 4, we recommended that all instructors check on students who are falling behind in any course to demonstrate that they have noticed their absence and are invested in supporting their success. This practice can be particularly important in online SJE courses, when the course content may be triggering for students, preventing them from reaching out. One instructor shared:

When students have gone more than a week without an assignment, I check in on them to see how they’re doing, what’s going on. . . . If we get to week seven or eight and there’s people that were doing really strong work early on, I’ll start talking to them about do they need an incomplete? What can we do to try to get them through the course material?

They noted that beyond the normal reasons students fall behind in online classes, personal reactions to the course content in SJE courses add another layer to students’ experiences that often requires additional instructor support. Recognizing that both outside circumstances and course content may affect student engagement, instructors should carefully consider the language used when reaching out to disengaged students. Leading with open and supportive questions that avoid making assumptions can demonstrate to students that you are interested in hearing about their experience and learning how best to support them. If you know something about a student’s situation that may be impacting their engagement, it can be helpful to acknowledge that point when reaching out. Additionally, as we discuss in more detail below, depending on a student’s situation, it may be appropriate to direct students to institutional support resources such as academic support services or mental health counseling.

Supporting Student Engagement with Course Content

This section offers considerations related to the structuring and presentation of SJE course content. Instructors teaching courses that they inherited and cannot change can consider implementing these strategies in the course syllabus, through periodic announcements, or other communication forms that guide students through the course material.

Be Transparent about the Course Trajectory and Emotional Load

Informing students at the start of the term about the content of the course helps students anticipate and plan for the emotional load associated with learning about discrimination and social inequities. Students will be more prepared to grapple with their emotions, recognize them as normative, and acknowledge them as part of the learning process. As Chick et al. (2009) found, Those who knew what to expect emotionally and those who learned that other classmates were having similar emotional experiences were more likely to stay with the learning process and grapple with new information, even when it generated uncomfortable feelings

(11). Given the importance of this information, and to increase the likelihood that all students will see the message, it can be useful to share it with students in multiple formats such as in the course syllabus, an introductory video, or as a conversation topic in an early discussion. Consider what approaches you may take if a student requests alternative content or assignments, and plan for flexibility as needed.

Provide Content Summaries

With online students engaging with course material in a variety of contexts, it can be informative to briefly describe each of the different learning materials rather than just listing required content or resources. This information can help students know what to expect so they can strive to be in both an emotional and physical space that allows them to engage with it meaningfully. For example, if a student knows there is a particularly challenging or graphic video to review, that information can help them avoid reviewing it with their children present or in a public space. Additionally, adding a content summary provides a space for the instructor to describe how each piece of content or resource fits into the class or connects with other course topics.

Content summaries are different from “trigger warnings,” which are a strategy for preempting symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder by identifying trauma-related topics, material, and discussions (Boysen et al. 2021). There is a body of research evaluating the effectiveness of trigger warnings, suggesting that they can increase emotional reactions before students view the material (Bridgland et al. 2024), so carefully evaluate their use in your context.

Adjust the Course’s Narrative Arc as Needed

Techniques that work in a face-to-face classroom to break tension and pivot in the moment when students are not grappling productively with the course content may not translate online. It may be necessary to reconfigure how and when course content is presented to compensate for the lack of real-time course correction. An instructor who transitioned from teaching their course in person to online noted, One of the things I had to change is I had to fill in some more positive stories early on.

In person they would spend over half the term talking about “really heavy topics” before transitioning into positive examples of resistance and resilience. This strategy worked in a face-to-face classroom. Online, without the ability to diffuse conversations or check in with students in the hallway before class, they observed that the tone of the class ended up being too dark, too long

and adjusted their course design accordingly.

Jen has experienced similar challenges in a course that addresses examples of power and privilege in environmental fields. Rather than concluding the course with examples of activists working to address systemic injustices in their fields, the course now includes activist profile assignments throughout the term to offer examples of how the discrimination and environmental injustices presented are being addressed. We encourage you to keep an eye out for how the tone of the course flows as you work your way through the semester, or solicit feedback from students through informal surveys at the midpoint or end of term to garner their advice for subsequent courses.

Direct Students to Institutional Support Services

Many SJE courses address themes that may touch students’ lives on a personal level. Students may disclose sensitive information in their assignments, and instructors may not be prepared to address it since most of us are not trained counselors or mental health professionals. An instructor describes using a trauma-informed perspective when considering how students may be impacted by the class content and how to support their capacity for self-care:

We talk early on in the course, particularly around if you had a friend or a family member, or you’re the counselor, or you’re the law enforcement officer, or you’re the attorney. How do you deal with somebody that’s telling you these things? How are you a support for them? How do you recognize what trauma looks like? But of course, at the same time, I’m sending them the message that this applies to you. . . . How do we use these things that you typically associate with trauma work . . . in terms of your own life?

When students’ needs extend beyond an instructor’s training to support them, directing students to campus support resources can be helpful. Including a page in your course that describes and links to institutional support services such as counseling and mental health services, survivor advocacy centers, affinity centers, or disability support services is a way to consolidate information for students. Knowing what resources are available at your institution and how to direct students to them, whether through links on a course site page or directly in personalized feedback, is important for supporting student learning and well-being. Additionally, it is critical that instructors are aware of institutional policies about mandatory reporting of sexual harassment or other harmful situations, as well as how to proceed if a student discloses information related to these aspects.

Additional Considerations

Teaching SJE courses online is an interactive and dynamic process, requiring instructors to self-assess, respond to student feedback, and make course corrections that require thoughtful planning to manage time and emotional load. The following considerations are offered to help you anticipate course needs that happen on an ongoing basis and behind the scenes.

Decide How to Present Yourself to Students

Instructors are continuously “read” by students, regardless of how much personal information we elect to disclose (Boovy and Osei-Kofi 2021). Students interpret clues and may make assumptions about instructors’ identities. In online courses, we have more leeway to thoughtfully withhold or reveal the (often more) visible aspects of our identities, such as race, gender, age, and disability status. One instructor reflected on how the visible aspects of their identity reflect dominant culture perspectives to students, but invisible aspects also influence how they show up in the classroom: I’m cis. Straight. I’m white. But there are other pieces that I bring to the table. Like I have disabilities. . . . I’ve raised queer kids. . . . I immigrated to the country when I was 10. . . . I don’t necessarily talk about those [aspects of my identity]. But I do know what it’s like to be in the room and not have your experience seen.

Instructors teaching SJE content also have different approaches to sharing their personal experiences in relation to course content. Sharing anecdotes can certainly personalize the content, build trust with students, and help to diffuse power differentials. Yet, as we discuss below, students may perceive social justice courses to be subjective or biased. When instructors share their lived experience with the content, it can reinforce these perceptions, so many instructors decide to withhold personal stories to maintain perceptions of professional distance.

One instructor we spoke with talked about the advantages of bringing their personal experience with discrimination into the discussion, weighed against the challenge of feeding student perceptions that SJE courses are subjective. The instructor observed, I think positionality and identity plays a big role in my class because I’m Black, I am not from the U.S. . . . I have experienced certain things that we talk about in the class—discrimination, hostilities . . . [It] has influenced my ability to navigate the topics that we talk about because I can share personal anecdotes from my experiences.

Despite having relevant personal experiences that could enrich the course and humanize both the instructor and the material, this instructor described how they wrestle with the decision about how much to lean into their personal stories, observing that students respond differently to material they perceive to be related to the instructor’s identities. If I started sharing experiences of how I’ve been followed in supermarkets, or how going to national parks, I’m the only person of color in an entire national park . . . If I share those ideas, my fear is that immediately students would start reacting very differently. So I try to avoid it, which I think may shortchange students,

they said.

This instructor’s observations are consistent with research findings that suggest students respond differently based on the perceived identities of their faculty in online classrooms (see, e.g., MacNell et al. 2015). They said that they have considered taking down photos and other visual clues to see if it makes a difference in how students engage. My inclination is [to see] what would happen if I remove my image on the portal and see how they would react to this anonymous person teaching the class if they don’t know how I look.

These decisions are personal and depend on your priorities, pedagogical style, and the risks involved in disclosing information related to your identity, rank, and potential for bias or discrimination. As you design your course, we encourage you to take time to reflect on the advantages and potential pitfalls of sharing your personal experiences in relation to course content.

Prepare for Additional Time and Emotional Labor Investment

There is inherent time and effort put into meaningfully engaging with students and teaching any class. With courses focused on social justice topics, additional time and emotional labor are necessary, as the material can evoke strong feelings that require more finesse when providing feedback. One instructor reflected, I know what I’m getting myself into by teaching the class. I know when I ‘walk into the classroom,’ what it is I’m walking into. And I think for people that don’t know it, the emotional stress can really get to you very quickly.

Students may need extra support when they show vulnerability and share about a lived experience or emotion; perpetuate a problematic narrative that needs careful course correction; or struggle to understand an idea. Knowing some of the common responses that may occur in response to the material and having comments and resources prepared to share with students can mitigate some of the time expenditure and also allow for a honing of feedback and resources about a specific idea. As one instructor shared, I’ve been teaching [this course] so long that they say the same things, so I have saved all of my comments from previous terms. So I don’t actually write my comments, I just cut and paste the comment from another term and put it in there. That’s [why] I can give so much feedback.

Another instructor described the individualized approach they take in responding to students’ journal assignments after each module. Some students tackle the reflective assignment from an academic perspective, while others share personal stories about how their lives have been impacted by the topics at hand. Providing personalized feedback based on what each student needs is an important way of building rapport, but it requires an additional time investment. The instructor observed,

I respond to every one of those with a personal response. If they’re an academic person, I’ll be like, “Did you look at this article?” or, “Oh, that’s a really nice twist on this other thing. Have you thought about it this way?” and try to push them from an academic perspective. And [for] people that are struggling with the inner personal perspective, [I say], “Here are some other resources.” Or “Wow. That’s really powerful. Thank you. I feel really honored that you trusted me with that information about you.” And “What are you doing this week to take care of yourself?” . . . That piece really lets you connect with students that want that connection.

In courses that require in-depth and personal feedback from instructors, including social justice classes, even a small increase in enrollment makes a difference, and unfortunately, decisions about course caps are often made without instructor input. Online course enrollment is not restricted by the availability of physical classroom space, so they are easy to increase, yet even a nominal increase in student numbers increases instructor workload. An instructor who teaches an online course on domestic violence reflected, Originally when I was hired [class enrollment] was 25 people, which was amazing. I really miss those days. Now it is 35.

All of the instructors we interviewed suggested that course size affects their ability to engage and support student learning. Another instructor observed:

The difference between like 25 and 45 [students] is massive. And the level of time and care and attention that I can devote to each of those students . . . Obviously, the greater the number, the more that gets split. Something I find concerning is when there’s a large number of students in the class: any number over 30 becomes unwieldy. Exponentially. With each student over 30, [it] becomes more and more difficult to keep a hand on the wheel and make sure everybody is getting what they need.

We recognize that instructors have varying levels of influence in departmental decisions like course caps. But instructors consistently emphasized that the ability to interact with students personally, in ways that demonstrate an investment in their learning, is essential and that their ability to do that well is directly correlated with class size. Wherever possible, we recommend advocating for enrollment caps that allow instructors to build meaningful rapport and support for students.

Plan to Manage Student Resistance

At OSU, we are extremely fortunate that the institution prioritizes educating students to recognize and disrupt systems of oppression. This commitment to social justice education safeguards instructors, to a degree, from pushback from students who feel challenged or threatened by content on themes of privilege and systemic injustice.

Although not unique to online courses or social justice courses, we sometimes meet resistance from students who struggle to engage with course material and assignments aimed to support learning outcomes centering diverse narratives, exposing historic and contemporary power, and challenging systems of inequity in US society. Such student resistance may escalate, demanding one-on-one engagement with the student beyond the typical levels of support, redirection, and feedback. Addressing resistance can move beyond pedagogy and require instructors to manage accusations of bias and threats by students against their instructional faculty. Again, these instances are not unique to online courses, but the lack of face-to-face relationship-building and accountability in an online environment, and the perceived anonymity typical of online comment sections, known as the online disinhibition effect (Suler 2004), may embolden students to behave in ways they may not in traditional classrooms.

We recommend reflecting on the considerations highlighted throughout this chapter when considering how to mitigate the added emotional labor of defending pedagogical strategies to resistant students. For example, establishing group norms for conversation and reviewing and discussing the course learning outcomes will set the tone early on and prepare students for what to expect.

One challenge in particular results from explicit commitments in course design to center the experiences of minoritized communities. Oftentimes this also means curating content and validating knowledge originating outside the academy. This is easy to do in an online course, with links to blogs, music, TED Talks, and other digital content. Resistant students may critique sources as nonacademic, and often, when the intention is to foster empathy through encountering a nondominant perspective, students who find it difficult to engage with authors whose experience differs from their own will say that the material is biased.

To curtail pushback, we recommend making these choices clear to students in your course syllabus, noting them as intentional and in alignment with the goals of the course to disrupt inequitable systems that maintain power and privilege. Pointing students back to the syllabus and the learning outcomes or other guiding principles of the course is a simple, direct response to pushback and accusations of instructor bias.

Engage in Ongoing Self-Reflexivity

Whether our classroom is in person or online, our assumptions, values, and biases (implicit and explicit) will influence our course design and teaching. Engaging in self-reflexivity can help instructors better recognize how we are showing up in the classroom and how to create more inclusive courses and learning communities. We recommend revisiting the questions in chapters 2 and 3, and offer additional questions to consider as you reflect on your teaching:

- How are you working to recognize your assumptions, values, and biases (implicit and explicit) and examine how they show up in your classrooms?

- What are the dominant narratives about the position and power of an educator compared to their students? What are your perceptions about this? How do expectations about power dynamics play out in an online classroom?

- How can you leverage your positionality to challenge inequitable structures and systems in your institution?

In addition to the importance of doing this work as individuals, we can use reflexivity as a teaching tool. Instructor introductions can be helpful in creating connections with your students, as described in chapter 3. You can also use them to model reflexivity and self-reflection about power and privilege from the beginning of the course. For example, after deciding how much to share with your students in light of the considerations highlighted above, a video could be used to share aspects of your positionality as they relate to class topics and name how they influence your lived experiences, privileges, and potential biases. This not only gets students thinking about the big ideas covered in SJE classes, but also sets the tone for the course by inviting students to engage with similar vulnerability, reflexivity, and self-reflection.

Conclusion

We hope the considerations in this chapter offer you a starting point for addressing challenges in teaching SJE courses in ways that promote decolonizing, as well as inclusive, efforts. This work is critical, and we recognize that SJE has been, and continues to be, politicized and weaponized in the United States and many other countries around the world. Instructional faculty and staff are losing their jobs; diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives are being cut; curricula have been outlawed. Where appropriate, we encourage you to discuss the considerations outlined in this book and other resources with colleagues who are also committed to transformative work as a way to build alliances and identify sources of support within your community.

Reflection and Action

In this chapter, we have presented considerations for online SJE course design and facilitation. If you are currently teaching or preparing to teach an online social justice course, we hope the suggestions provided are helpful in reflecting on your own experience and the dynamic and contextual nature of teaching. Chapter 7 includes a discussion of the Inclusive Teaching Online workshop and outcomes from research with instructor participants.

You Might Be Ready to . . .

- Practice reflexivity by critically thinking about the questions posed in the “Engage in Ongoing Self-Reflexivity” section.

- Briefly describe learning materials in your syllabus or your course site so students can better assess the emotional and physical space they will need to engage with the material.

- Consolidate and share a list of support resources available to students (e.g., counseling and mental health services, survivor advocacy centers, affinity centers, disability support services, etc.).

- Consider ways to interrogate power dynamics within your classroom and institution with colleagues.

Questions for Further Consideration

- How can I engage in further self-reflexivity about my positionality and teaching practices?

- What narratives are being perpetuated or interrogated in my online course?

- Who are allies in this work on campus and in my community?

References

Adams, Maurianne, Lee Anne Bell, Diane J. Goodman, Davey Shlasko, Rachel R. Briggs, and Romina Pacheco. 2022. Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice. Taylor & Francis.

Bell, Lee Anne. 2016. “Theoretical Foundations for Social Justice Education.” In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice, 3rd ed., edited by Maurianne Adams, Lee Anne Bell, Diane J. Goodman, and Khyati Y. Joshi Routledge.

Boovy, Bradley, and Nana Osei-Kofi. 2021. “Teaching about Race in the Historically White Difference, Power, and Discrimination Classroom: Teacher as Text.” In Transformative Approaches to Social Justice Education: Equity and Access in the College Classroom, edited by Nana Osei-Kofi, Bradley Boovy, and Kali Furman, 189–204. Routledge.

Boysen, Guy A., Raina A. Isaacs, Lori Tretter, and Sydnie Markowski. 2021. “Trigger Warning Efficacy: The Impact of Warnings on Affect, Attitudes, and Learning.” Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 7 (1): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000150.

Bridgland, Victoria M. E., Payton J. Jones, and Benjamin W. Bellet. 2024. “A Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Trigger Warnings, Content Warnings, and Content Notes.” Clinical Psychological Science 12 (4): 751–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026231186625.

Chick, Nancy L., Terri Karis, and Cyndi Kernahan. 2009. “Learning from Their Own Learning: How Metacognitive and Meta-Affective Reflections Enhance Learning in Race-Related Courses.” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030116.

Considine, Jennifer R., Jennifer E. Mihalick, Yoko R. Mogi‐Hein, Marguerite W. Penick‐Parks, and Paul M. Auken. 2017. “How Do You Achieve Inclusive Excellence in the Classroom?” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 151: 171–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20255.

da Silva, Ileana, David Rogers, and Amy E. Arnett. 2024. “‘Welcome to My Backyard’: An Intersectional Approach to Inclusive Teaching in the Asynchronous Learning Environment.” Distance Education 45 (3): 446–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2024.2355538.

Dumford, Amber D., and Angie L. Miller. 2018. “Online Learning in Higher Education: Exploring Advantages and Disadvantages for Engagement.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 30 (3): 452–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-018-9179-z.

Grosfoguel, Ramon. 2013. “The Structure of Knowledge in Westernized Universities: Epistemic Racism/Sexism and the Four Genocides/Epistemicides of the Long 16th Century.” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137292896.0006.

Hanesworth, Pauline, Seán Bracken, and Sam Elkington. 2019. “A Typology for a Social Justice Approach to Assessment: Learning from Universal Design and Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (1): 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1465405.

He, Le. 2022. “Pathways to Social Presence in Online Learning Communities.” Learning and Education 10 (8): 91. https://doi.org/10.18282/l-e.v10i8.3070.

Joseph-Salisbury, Remi, and Laura Connelly. 2021. Anti-Racist Scholar Activism. Manchester University Press.

Kear, Karen, Frances Chetwynd, and Helen Jefferis. 2014. “Social Presence in Online Learning Communities: The Role of Personal Profiles.” Research in Learning Technology 22 (January): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v22.19710.

Machado de Oliveira, Vanessa. 2021. Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism. North Atlantic Books.

MacNell, Lillian, Adam Driscoll, and Andrea N. Hunt. 2015. “What’s in a Name: Exposing Gender Bias in Student Ratings of Teaching.” Innovative Higher Education 40 (4): 291-303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9313-4.

Myers, Jenny N. 2021. “Critical Pedagogy Online: Opportunities and Challenges in Social Justice Education.” In Transformative Approaches to Social Justice Education: Equity and Access in the College Classroom, edited by Nana Osei-Kofi, Bradley Boovy, and Kali Furman, 87–104. Routledge.

Osei-Kofi, Nana, Bradley Boovy, and Kali Furman, eds. 2021. Transformative Approaches to Social Justice Education: Equity and Access in the College Classroom. Routledge.

Phirangee, Krystle, and Lorne Foster. 2024. “Decolonizing Digital Learning: Equity through Intentional Course Design.” Distance Education 45 (3): 357–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2024.2362413.

Russell, Jacqueline Y. 2010. “A Philosophical Framework for an Open and Critical Transdisciplinary Inquiry.” In Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination, edited by Valerie A. Brown, John A. Harris, and Jacqueline Y. Russell, 31–60. Earthscan.

Samuel, Anita. 2024. “Decolonizing Online Learning: A Reflective Approach to Equitable Pedagogies.” Distance Education 45 (3): 439–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2024.2338720.

Stein, Sharon, Cash Ahenakew, Elwood Jimmy, and Vanessa Andreotti. 2021. “Developing Stamina for Decolonizing Higher Education: A Workbook for Non-Indigenous People.” Accessed December 14, 2024. https://decolonialfutures.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/decolonizing-he-workbook-draft-march2021-2.pdf.

Suler, John. 2004. “The Online Disinhibition Effect.” CyberPsychology and Behavior 7 (3): 321–26. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295.

Watters, Audrey. 2018. “Foreword.” In An Urgency of Teachers: The Work of Critical Digital Pedagogy, by Sean Michael Morris and Jesse Stommel. Hybrid Pedagogy. https://pressbooks.pub/criticaldigitalpedagogy/.