2 Oversights about Online Students and the Barriers They Face

Introduction

Online courses often create student barriers by way of assumptions about student needs or teaching behaviors that do not promote student success. We call these barriers because, while they are not insurmountable, they can have a negative impact on learning and the overall course experience, requiring students to exert extra time, energy, and persistence to move past them. When we are thoughtful about proactively serving all online students, we can meet a wide range of needs up front, and that work begins by unpacking lingering assumptions that may not be true and by intentionally avoiding teaching behaviors that we know do not serve students well.

Online instructors face a special challenge in that they may have limited preliminary access to data about their students—who they are and how their learning progresses during a course. Perhaps each student’s profile just lists a campus code, major, and a place of residence, and no other information is available unless students are asked to share more directly with their instructor. In an on-campus course, instructors have visual indicators of the demographics of their class, such as if students are primarily younger or older adults. Online instructors may have more difficulty tracking trends or even just getting a sense of who has enrolled in a particular course section. Asynchronous online courses also lack visual and nonverbal cues that are present in on-campus course meetings. Instructors who are new to online teaching often lament that they cannot see if students are nodding along as information is shared or if students look wholly confused, preventing instructors from responding accordingly. In the online classroom, cues about student progress are more subtle—a brief mention in a discussion post might disclose that the student finally “got it,” or an assignment may reveal that they have not connected key concepts for the week—or the cues may be hard to find at all. As a stopgap, an instructor may have to make more inferences from the course gradebook to assess trends in student progress. But we recommend acknowledging those challenges around student data and then setting them aside in favor of a more proactive approach to inclusive online teaching, one that emphasizes removing barriers. As discussed in the introduction to this book, we aim to give instructors tools to take barrier management off of students and identify more universally effective approaches for inclusive online teaching.

Many online instructors offer lines of communication for students to seek help if they encounter a barrier, but it is worth noting that students will not necessarily make use of that offer. Students’ negative experiences with teachers may start early in their education, perhaps in unwelcoming learning environments (Essien and Wood 2022), and those experiences can continue to influence their educational journey all the way through college or graduate school. Student success staff can be helpful partners in identifying patterns of preexisting concerns and anxieties in a particular institution’s or program’s student group. OSU Ecampus students have shared with their student success coaches the following reasons why they hesitate to reach out to their instructors or otherwise connect with them (Racek 2020):

- Self-doubt (e.g., lacking the ability to figure things out themselves)

- Uncertainty regarding instructor response or perception (e.g., not wanting to “bother” instructors)

- High expectations of self (e.g., asking for help is a sign of weakness)

- Negative experiences from the past (e.g., a former professor did not understand a personal situation)

- Unclear or missing instructor communication policy (e.g., no information about office hours or appointments has been provided)

- Minimizing the importance of their concern (e.g., it is not an emergency, so it’s not worth bothering the instructor about)

Most of these reasons originate in previous experiences, but consider how a small trigger in a current course may make students recall a previous negative association. An unintentional omission of office hours available by appointment, for example, could deter a student from reaching out to their instructor under the (mistaken) interpretation that the instructor is not interested in meeting with students. That said, teaching online is an opportunity to think proactively about the students who are enrolling and how to serve them well. A critical part of that work entails unpacking assumptions about who students are and how they engage effectively in online learning. In this chapter, we examine oversights about online students and teaching behaviors that can create barriers to student success. The goal is for your students to think, “This course is for me!” when they get started.

In the first section, we address six specific oversights about online students, derived from conversations across our faculty development workshops, collaborations, and consultations at OSU Ecampus. Each is described and then made more tangible through a scenario based on real-world experiences of online students. Possible next steps relative to the scenario are presented to spur initial thinking and actions about alternative perspectives and approaches. Reflection that you do regarding persistent assumptions about online students as part of this chapter will serve you well moving into chapter 3, where we discuss instructor self-introductions and how to set the tone for your course. Chapters 4 and 5 provide a comprehensive set of inclusive teaching strategies to respond to the needs of online students.

In the second section, we identify two additional instructional behaviors in online teaching that create significant barriers for students. Unpacking how those behaviors may be perceived by and affect students can help build awareness around those barriers. This section, too, supports work for chapter 3, as you will be able to more effectively articulate to your students who you are and how you plan to interact with them.

Six Oversights about Online Students

The oversights presented below most often stem from long-standing generalizations about learners (many of them outdated or overly simplistic) that are then extended to online learners. Consider if any of these oversights have shaped your thinking about and work with online students.

Oversight 1: Online Students Share Similar Approaches to and Perspectives on Learning

Reality: Online students bring a variety of ideas about learning, its purpose, and classroom interactions to online courses.

As the cultural diversity of our online students increases (Tereshko et al. 2024), we need to think beyond our own frames of reference about teaching and learning approaches and processes. Many of us have designed courses following the models of instructors who taught us, and we have a tendency to teach in the same way we learned or were taught (Mazur 2009). But the reality is that we cannot assume that others will learn in the same way we do, because that assumption can create barriers for students (Messineo 2018, 16). Online students come to the classroom with their own ideas and perspectives about learning—many derived from cultural worldviews that are shaped by their upbringing and their social context. “Culture” is a broad term and can touch on any number of aspects of identity—race, ethnicity, nation of origin, preferred language, proficiency in the target language, religious and spiritual beliefs, and more—but cultural influences play a substantive role in our ideas about education, including teaching practices and specifically about defining the roles of teacher and student.

A student’s cultural background can impact their experiences, feelings, and perceptions of the contexts in which they interact, including ways of thinking and being in the world that relate directly to educational contexts. For example, some cultural groups value holistic, formal reasoning rooted in individual cognitive efforts, while other groups prefer analytic, intuitive reasoning (Nisbett et al. 2001) and cooperation and value of learning in community (Moule 2012). Extending this idea to a diverse, multicultural online classroom, Ke and Chávez (2013) argue that distance learning practices and approaches are often not aligned with students’ life experiences and practices. That misalignment can occur because your students may or may not approach thinking, reasoning, and learning in the same way that you do, possibly creating a disadvantage for students from diverse cultures. Developing an awareness of the ways that cultural differences affect expectations of teaching and learning can help us make a conscious effort to acknowledge that students bring their backgrounds with them to the online classroom, and that those backgrounds have real impacts on how (and if) students engage with instructors and peers. Such an awareness, in turn, can inform design choices that better address the needs of online students and leverage cultural diversity as a positive strength, often called an asset-based approach, in contrast with the (problematic) deficit approach that emphasizes what a student may lack.

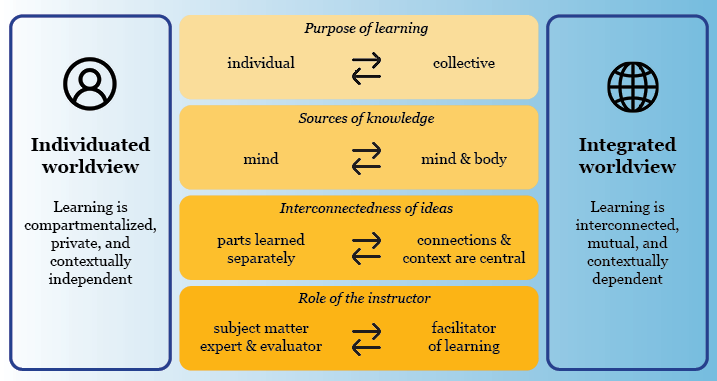

Research on how students might interact differently in online courses based on cultural factors has been somewhat limited; there are many frameworks that can inform educational practices, including learning design (which we discussed in chap. 1), but these frameworks may have limitations in exploring people’s behaviors (Långstedt 2018). Ke and Chávez (2013) conducted an important two-year, mixed-methods study at a southwestern university in the United States to explore “the impact of online pedagogies and contexts on the learning processes and perceptions of a diversity of college students living in rural and urban areas, with an emphasis on learners of nontraditional age and minority status . . . across 12 academic disciplines” (13). This study provided a cross-cultural and intergenerational framework for exploring individuated and integrated approaches to teaching and learning (fig. 2.1). The resulting framework is especially relevant for instructors invested in adopting inclusive teaching methods because many of the current practices in college classrooms rarely “include knowledge of activities similar to those in home communities of most students of color . . . Further, these cultural norms are rarely considered strengths or ‘cultural wealth’ that students bring with them into collegiate learning environments” (Ke and Chávez 2013, 21). Importantly, this framework gets at the many ways of being that significantly shape and impact learning, not just student learning “preferences,” and that ultimately influence whether or not a student is set up to succeed in an online course. Not attending to the cultural and individual differences of students could result in online teaching practices that are “at odds with ways of thinking, acting, and being that students bring with them” (Ke and Chávez 2013, 28).

Ke and Chávez (2013) note the following.

- Individuated approaches are common and often dominant in US society, originating specifically from northern European cultural practices (94-95).

- Integrated approaches are more common to Hispanic and Native American groups, and may also be common to Indigenous groups from Southeast Asia, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand as well as Latino groups originating from southern Europe, South and Central America, and Mexico. Some aspects of integrated approaches may be common among African American students as well (96).

- Further exploration into the cultural epistemologies of students originating from the Middle East would likely reveal similarities with the integrated approach (96).

Ke and Chávez’s (2013) framework for online learning can help identify practices and preexisting inclinations across a spectrum of cultural approaches. While many academics and instructors with backgrounds in Western-centric cultures may be tempted to fall into dualistic thinking, or an identification with one side of the spectrum or the other, the most helpful way to use this framework is to see that both teachers and learners may locate themselves somewhere along the spectrum by identifying with aspects of both constructs. Our tendencies and areas of comfort in these aspects of teaching and learning are also contextual and not fixed; for example, we may have grown up learning one way but adjusted and adapted in later learning experiences, perhaps out of necessity because we found ourselves in an educational setting that took an approach that was different from what was familiar to us.

Consider where your inclinations fall on each spectrum in figure 2.1, and identify any consequences they have had for how you design and facilitate online courses. There may be opportunities to vary your approaches to teaching or the ways in which students engage in learning; this is not necessarily a matter of accommodating all learning approaches but ensuring that students feel supported even when you might ask them to engage in an unfamiliar way. Clear instructions and guidance help make the “what,” “how,” and “why” of any task more transparent (much more on this approach in chap. 4). As an additional example, a collaborative, multistage group project could ask students to develop individual parts of the project—allowing them to lean into cultural constructs that value personal responsibility and achievement—while collaborating with peers to create the final version of the project, thereby also facilitating learning in community and with teamwork.

Scenario: Marcus’s cultural upbringing shaped his approach to interpersonal communication such that challenging the perspectives of others is seen as disrespectful or confrontational. In one of his online classes, he is asked to engage weekly in a small group debate on the discussion board, and his peers express their disagreements and criticism in direct ways that clash with Marcus’s norms for communicating with peers. He feels hesitant to engage in this format and in the tone and style his peers are using, preferring a more cooperative style of communication where group members take turns sharing and listening in an attempt to reach a shared understanding. His silence over the course of the first debate is perceived by his groupmates, and by his instructor, as disengagement or lack of interest in the activity.

Possible next steps: Marcus’s cultural background and perspective on respectful dialogue clash with the norms of a Western-centric approach to engaging in debates. This discrepancy could cause Marcus to feel anxious as he attempts to participate, and he may wonder whether a more comfortable approach to dialogue does not meet his peers’ or his instructors’ expectations. Exploring the spectrum of individuated and integrated approaches to teaching and learning (fig. 2.1) can help us to better understand how these influence the student experience, possibly prompting us to alter the design and facilitation choices we make. What can seem like a straightforward discussion assignment to an instructor could be confusing or distressing to a student, as in the example above, so being open and willing to take a step back and look at course tasks and prompts from non-Western-centric cultural perspectives can present opportunities to remove possible barriers for students. A more integrated discussion assignment might give students an opportunity to select and rotate discussion roles and to build cooperatively toward a final conclusion about the topic at hand. For instance, a discussion activity can ask students to share the connections and value they see between the topics, employing their lived experiences or perspectives of the communities in which they interact (including the small discussion community in the class) before they engage in analysis of the content discussed together.

Oversight 2: Online Students Are about the Same Age as “Traditional” Campus Students

Reality: Online students tend to be older adults, but student age can vary widely.

Online students can belong to various adult age groups. As we discussed in the introduction to this book, however, many online students tend to be closer to midlife and mid-career than to be just out of high school or nearing retirement. Designing or facilitating an online course under the assumption that students are younger or otherwise more “traditional” or “college”-aged or “younger adult” students (often defined in educational research as 18-25 years old) can feel off-putting for adult students (over age 25 and under age 65) because they are at different life stages and may be seeking different outcomes from their educational experiences.

Age and its specific impact on online learning is complex, and to date, studies have provided mixed results, possibly due to a limited or unclear definition of what constitutes an adult or older student (Decker and Beltran 2016). Some research suggests that age has a limited impact on the online learning experience, but it is relevant to how students interact with their peers. For example, in a study on deep learning, adult students (24-59 years old) self-reported “the same level of learning satisfaction and time/effort on learning tasks” as more traditional-aged students (Ke and Xie 2009, 143). Relatedly, a study comparing three age groups (18-25, 26-35, and 36-55 years old) identified that students in the 36-55 age group felt more comfortable than the other age groups when it came to interacting and disagreeing with peers while maintaining a sense of trust in online discussions (Decker and Beltran 2016).

Yet age does play a role in online learning, for various reasons. Adult students are likely to bring into the online course more significant work experiences than younger, “traditional” students, and adult students often have an intrinsic motivation beyond receiving a grade (Slover and Mandernach 2018). In addition, adult students’ willingness to share and interact more in the online class could be “a function of their maturity that often overlaps with age” (Decker and Beltran 2016, 22). The fact that adult students bring with them a wealth of knowledge, practices, and tools to the online space is worth noting for student interaction, especially when activities and assignments are in groups and integrate student choice. Adult students are more invested in their learning when offered choices or input because they are free to explore topics and activities that are closely related to the course objectives while integrating their own interests and life and work experience. Research shows that student choice leads to increased engagement, effort, and ownership of learning (Marzano et al. 2011; Henrikson and Baliram 2023; Simunich et al. 2023) and can “enable students to be self-directed learners. It can allow students the autonomy to choose methods that are most engaging to them” (Henrikson and Baliram 2023, 17), practices supported by transformational learning (discussed in chap. 1). Courses where this type of flexibility is not available, by contrast, can feel constraining and less engaging to an adult student.

The intersection of age with career and life trajectory can impact how adult students experience the online classroom. Adult students tend to be working professionals, holding part-time or full-time jobs on top of school, and they are also likely to have family responsibilities such as parenting or caring for extended family members (Wildavsky 2021). Instructors may believe that an online class inherently gives students all the necessary flexibility to manage on-time assignment submission, active and early participation in course discussions, and so on, but in reality, adult students are constantly making difficult decisions about which tasks take priority. When they have a work deadline, a sick child, and an essay assignment due, which should they attend to? Even more factors may come into play, such as time management and self-regulation skills, academic preparation, course availability, institutional support at times when they can engage with it, and so on (Kara et al. 2019; Stephen 2023).

Some online learners do fall in the traditional 18-25 age range. They may be campus-based students looking for some additional flexibility in their class schedule, or perhaps the on-campus course section was full at registration time. They could also be pursuing careers that require travel or scheduling flexibility; world-class athletes have pursued their education online at OSU, for example, while engaging in frequent travel for sporting events. It is also possible to have older adult learners (65+) in your course who are looking for a new learning challenge or an intellectual community; OSU Ecampus has served students pursuing undergraduate and graduate degrees in their 70s and 80s. If you find that these age groups are a part of the population that you are teaching, consider how to account for their needs. The recommendations in this book will generally serve all students well even as they help you to serve 25- to 65-year-old adult online students more effectively.

Scenario: Dex is excited about returning to school and taking their first upper-division course within the business major. It is capped at a small size to encourage instructor–student interaction, allowing students to get to know the instructor well enough that they could provide a letter of recommendation later. As Dex reads through the course’s syllabus, they are disheartened to find that the instructor only offers office hours from 1:00 to 2:00 p.m. on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and there is no mention of an option to meet by appointment. As a full-time employee, it is unlikely that Dex will be able to attend office hours for a one-on-one conversation. They are also dismayed to see that one of the key course support resources noted in the syllabus is for first-time resumé writing help. At age 37, Dex has held many jobs and is confident in submitting job applications.

Possible next steps: Knowing your course’s audience is key, and intentional gestures as early as the course syllabus can signal to students that you consider their individual and collective needs. Many online instructors hold some or all office hours by appointment to ensure that their students know that there is an option to go beyond email or course messaging, talking synchronously at a mutually agreeable time. Consider, too, what life and work experience students are likely to bring to the course. How can those experiences not just be acknowledged but even leveraged to enrich discussions and individual work? If you are unsure of who your students are (perhaps when you are teaching a course for the first time), consider ways to find out. Academic advisors can provide insights, and surveying students at the beginning of the course can help you identify students’ specific needs.

Oversight 3: Online Students Can Adapt to Rigid Course Structures and Policies

Reality: Online students are pursuing their education in spite of many challenges, and they need reasonable flexibility.

Online students have complex schedules because they are often juggling multiple responsibilities while they pursue school. These students may have many family and work obligations, experience disabilities or chronic illnesses, be located in different time zones, or be responsible for other obligations. In addition, many students have one or more of these characteristics: they may be returning to college at a later time, be part-time students, have a full time job, be financially independent, have dependents, be a single parent, or have a general educational development (GED) credential (Puzziferro and Shelton 2009). Taking online courses is often the best—or only—way that students can weave school into the other parts of their lives. The flexibility that online education affords in terms of when and where students engage does not mean that students have unlimited flexibility when it comes to their participation in an online course.

From a course design perspective, a clear structure is needed to support students and give them a path to follow through the course, but structural elements that are too rigid can undercut the very flexibility that online students rely on. Examples of these structures and their negative effects include:

- Sequences of tasks that are required to be done in a particular order, such that only one activity is available to view at a time; learners may need to look ahead and make choices about which activities to do in the time that they have available on a particular day, for example.

- Mandatory engagement with activities on a specific and short timeline, like watching a lecture video and taking an associated quiz on Monday, posting discussion comments by Wednesday, replying to peers by Friday, completing homework by Saturday, and sharing reflections by Sunday. Learners need maximum (reasonable) flexibility to engage in the content across a week/unit/module, and they may not be able to access and engage in the course as frequently as or with the precision that the above schedule requires.

Likewise, rigid course policies can disadvantage the adult students who are balancing life, work, and school obligations. A common theme in annual survey feedback from OSU Ecampus students is how much a blanket “no late work” policy hampers their ability to successfully manage competing priorities. Students appreciate even a small amount of flexibility when it comes to deadlines (we will consider reasonable options in chap. 4). An online student might be faced with the difficult choice of completing a work deadline on time, taking care of a family member, or completing a course project, and that decision would weigh even heavier if their instructor does not accept any late work, for any reason.

Scenario: Carolina is a part-time student and member of the Army National Guard. She switched from campus-based courses to online courses so she could study independently, completing the assignments around her work schedule. In the new term, she discovers that her course has recurring, graded learning activities that are always due on weekdays, frequent homework and essays with weekend deadlines, and the syllabus indicates that no late work is accepted. Carolina is taken aback by the inflexibility of the course, and without options decides to take the grade deduction for any small assignments that she cannot complete. When an unexpected National Guard training exercise conflicts with a major assignment deadline, Carolina notifies her academic advisor that she will need to drop the course and adjust her degree completion plan.

Possible next steps: High-structure elements and required timelines should be considered carefully. Are they necessary, or might they be creating unintended barriers? Also, reflect on deadlines and late-work policies in your course and what function they serve. Keeping students on track so that they space out their learning across the course (and do not attempt to complete a full-term course in a few weeks, for example) is reasonable, but allowing for some grace around deadlines can support students while not impeding instructor progress on providing grades and feedback in a timely manner. Allowing some flexibility will support students like Carolina who have extenuating circumstances and who may not be comfortable asking for an exception. Many Ecampus instructors at OSU now provide one or two no-questions-asked late-work “passes” per student, managed through a simple form. Students can decide when to use the passes and do not need to provide justification to use them.

Oversight 4: Online Students Have Excellent Access to and Proficiency in Technology

Reality: Online students’ technology access may vary widely, as may their technological proficiency.

Individuals involved in online course design (instructors, instructional designers, etc.) oftentimes assume that students have strong broadband access. A course might rely heavily on video content that needs to be streamed and cannot be downloaded, interactive elements that need to load in full to function, large file downloads for assignment templates, exam proctoring apps that require strong and consistent bandwidth, and so on. Courses with multiple strict deadlines each week, as discussed in the section above, also presuppose that students have modern devices and highly reliable Internet access, allowing them to connect most, if not all, days of the week.

Many regions of the world, however, including many rural areas in the United States, still lack broadband Internet access. Infrastructure investments are lessening the gap in availability between rural and urban residents, but as of December 2022, an estimated 24 million Americans were still not connected at home, including 28% of Americans living in rural areas and 23% on tribal lands (Federal Communications Commission 2024). A student living in a rural area who wants to engage in higher education may only be able to attend online, yet that same student may not have reliable access to the Internet at home and may need to travel somewhere with a stronger connection to download course materials and upload their assignments. An online course developed with diverse learner needs in mind might consider Internet access as a design challenge. How might a course be designed effectively if students could only log in a few times a week, and perhaps for only an hour or two at a time?

Students who access their courses from abroad may run into another challenge because other countries sometimes block web access to US-hosted technologies. Lists of what is blocked are not usually maintained and may not be accurate, so students may not discover until they try to engage with a resource or tool that they cannot access it. Offering choices (or being prepared to offer choices) of resources and tools can help to mitigate the risk of a student not being able to complete activities and assignments.

We also cannot assume that students are using any particular type of device to access their online courses. Dello Stritto and Linder (2018) investigated students’ device preferences to access their online courses and multimedia course materials by surveying approximately 2,000 students (undergraduate, graduate, and other) taking at least one online course. The results revealed that 67.7% of students preferred laptops, 19% desktops, 6.5% tablets, and 5.5% smartphones to view video lectures. While the study shows a high preference for laptops, we should also anticipate that, in reality, many students access their online courses from multiple and different devices. For example, students may check messages or grades from their phones. Working adult students may want to listen to lecture podcasts on their phones while they commute or travel, while others might want to post to a discussion board using their smartphones or tablets. These devices could also be older and not able to run the newest versions of applications.

Remember, too, that the complexity of educational technology is an important consideration in online courses because its use is always required. Sometimes online instructors assume that because students are taking an online course, they are fluent with web- and application-based technologies. In reality, online students may have a wide variety of exposure to and experience with technology, with at least some students being less savvy. Students who grew up in a less technology-saturated world may find it especially challenging and time-consuming to troubleshoot an unexpected challenge or error. Even when students can develop transferable digital skills, they may experience anxiety about having to master two sets of knowledge and skills—course topics and new technologies—simultaneously (Safford and Stinton 2016). Care should also be taken if and where social media technologies are integrated into a course. While some research suggests that social media tools offer opportunities to enhance learning through networking and participatory engagement, some students may perceive that these tools offer little value in academic settings and formal learning. Students might also be unwilling to blend their personal, academic, and professional details in social media tools, or they may find them challenging and intimidating to use (Salmon et al. 2015).

Scenario: Aiyana lives on a reservation and is an education major. She does not have Internet access at home and must travel nearly an hour to reach a coffee shop with public Wi-Fi, so she accesses her courses about three times weekly in the evenings. In her current course, the instructor asks for students to engage with a generative artificial intelligence (GAI) tool to brainstorm a lesson plan idea, to check alignment with the practice learning outcomes, and to assist in developing a rubric. At each stage, students must document in detail their iterative conversation with the tool. Aiyana is unsure of whether she should stay in the course or ask her instructor for an alternative. There are few guidelines about how to engage with the GAI tool ethically and effectively, and she worries that figuring out how to have a productive, iterative conversation and then document it will take too much time. Those activities are also something she cannot work on from home because they require an active Internet connection.

Possible next steps: Consider how to make your online course maximally flexible for students who may have varying levels of access to the Internet at different times and places, different devices, and a wide spectrum of technological proficiencies. If in doubt, always provide resources, guidance, and ideally options so that students can spend more time learning the content and skills in your course and less time grappling with technology. Weigh key considerations and options before requiring GAI tool use. GAI tools that are institutionally supported are generally the best options for data protection and user support, but students may still encounter bandwidth issues, misinformation, and bias, and students may raise concerns about ethical issues and the environmental impact of running many GAI inquiries.

Oversight 5: Online Students Have Above-Average Reading and Writing Skills

Reality: Online learners may or may not have strong reading and writing skills, and their preferences for text-based communication may vary.

Asynchronous online courses have traditionally been developed with a heavy emphasis on text-based communication, and with good reason: course and instructor-generated text provides clarity of information and instructions, helps students navigate a course and locate information and supplemental content, and increases accessibility through image-related descriptions (Moore 2021). Moreover, writing is a form of active thinking and learning, and thoughtfully engaging students in reading and writing development activities is a strategy to promote their success (Klein et al. 2016). Even low-stakes writing activities like discussion posts can develop higher-order and metalinguistic thinking (Lapadat 2002). While we acknowledge the important role that reading and writing can play in an online course, we invite you to also think about the barriers that can arise from an overreliance on reading and writing in online courses for students who might prefer to learn and to demonstrate their learning by other means. Casareno (2010), for instance, argues that college courses may unintentionally make success hinge upon a student’s reading ability, and Griffin (2018) cautions that more writing does not necessarily lead to better learning outcomes in online courses.

Consider the means by which content is communicated in your course. Are all learning materials readings? Are there some options for lectures, videos, podcasts, or other multimedia? A course that relies heavily or entirely on readings might benefit from “instructor notes” that guide students as they work through the set of materials for each unit or module. Alternatively, integrating social annotation tools (e.g., Perusall and Hypothesis) can provide students with a collaborative reading space for asking questions and sharing ideas among peers and with their instructor. (Instructors can seed questions and notes on materials ahead of students engaging with them as well.) To support online learners with a wide variety of linguistic backgrounds and academic skills, clarity is critical in course text and can be a lens through which to review external materials (textbooks, books, articles, etc.) as well as text written for and within the course itself. If students are unable to understand complex instructions or are unfamiliar with the jargon used, they will face challenges in meeting the expectations and outcomes. Shapiro and Aull (2023) posit that many students, especially from marginalized backgrounds, might feel alienated when they encounter unclear terminology; therefore using “plain language” can help to communicate with students more clearly and ease their reading processing. These scholars acknowledge that there “may be a role for specialized terminology and dense grammar in scholarly conversations among experts,” but there are opportunities to support students by making “linguistic choices that invite others in rather than blocking them out” (para. 12).

Overreliance on writing to demonstrate learning progress or mastery can disadvantage multiple student groups. Research has shown the prominence of writing anxiety among college students—especially for female students and those who are already experiencing academic challenges (Martinez et al. 2011) as well as students who are learning the language of instruction (e.g., English) and the discipline at the same time. One possible solution is to consider two types of writing prompts that are common in undergraduate and graduate coursework: “writing to learn” activities, where writing is both a process and a product, and “writing to communicate” activities, which simply pose writing as the instructor’s preferred means of communication (Balgopal et al. 2018, 445-46). Activities and assessments that only focus on communication of ideas type can often be revised to offer additional options. Universal Design for Learning, which we discussed in chapter 1, is a useful framework to provide students with multiple means to access content (e.g., video, audio, text, graph), demonstrate knowledge and skills (e.g., videos, presentations, graphics), and engage and collaborate with others (e.g., student choice, peer interactions) (CAST 2025).

Scenario: Maitane is taking an online engineering course in order to balance her part-time work and motherhood. French is her first language, and she faces significant challenges in keeping up with the demands of the online course, where success seems contingent upon reading skills (conducting library research in technical articles) and writing proficiency (research summaries, discussion posts, and written projects). Deciphering complex topics and academic jargon can be a daunting task, and expressing ideas effectively in writing and interacting with peers prove challenging to Maitane. These challenges also spur a sense of frustration and self-doubt. The final assignment is a research paper, even though the course is not a writing course and the course learning outcomes do not require a written artifact to measure the outcomes. The paper requires students to conduct a literature review, provide primary sources in support of key claims, and use academic conventions in their discipline. Maitane, who has some working experience in the technical field and with writing reports, has not written a research paper before and is unfamiliar with its structure and process.

Possible next steps: Revisit the course to determine where literacy skills are explicitly part of the course’s learning outcomes and where there may be opportunities to let students produce something other than a written product. If you have or are implementing “writing to learn” activities in your course, look to best practices in the field of college writing instruction, particularly to experts in the online modality and experts in writing across the curriculum (WAC). Beth Hewett’s Reading to Learn and Writing to Teach: Literacy Strategies for Online Writing Instruction (2015) provides many helpful approaches and ideas for online instructors. Additionally, build in as many supports and resources as possible to aid students who may find reading and writing challenging; information about your campus writing center or library can be helpful, for example, and many students benefit from tools that help them build fluency in reading academic literature over time. But if your course does not require a deep focus on reading and writing, consider other means for students to acquire and demonstrate knowledge.

Oversight 6: Online Students’ Top Priority Is School

Reality: Online learners are often busy with work, family, and school obligations, and they cannot always prioritize coursework.

Our discussion of the oversights above have already surfaced some of the many challenges that an online student might face. One final oversight that we want to call attention to is the perception that online students can always make school their first priority when, in fact, they may be involved with many obligations that compete for their time, mental bandwidth, and financial resources. Coursework will not and cannot always be the center of their focus. Payne et al. (2023) point out that “Universities in the United States often reflect middle-class norms and values where students are expected to engage in independent learning separate from their family and focus solely on personal academic and life goals.” Online learners, however, are most often in a much different position. They are usually interdependent with their families and communities, and they are usually not focused solely on personal goals.

Consider, too, what happens when students face not just one challenge but multiple, and when each challenge intensifies the others. A student might be in a precarious financial situation that causes them to choose between groceries and buying textbooks, and then their laptop breaks and they cannot afford to replace it before finishing out the term. Another student might share that they are balancing tending to the family farm, attending school part time, and caring for an elderly parent, and then they suddenly experience catastrophic flooding that wipes out their home. Yet another student might appear and disappear throughout a term with no explanation, only to disclose near the end of the term that they are going through a contentious divorce and both they and their children are struggling with mental health. If you are serving students who are veterans of the US military and are eligible for GI Bill benefits, you should also know that these students receive significantly less funding for their monthly housing allowance when they take online coursework, which may affect their overall financial stability while they are in school (Riggs 2022).

These examples represent just a small portion of the real life challenges that our students face, and all of these examples could compound anxieties about paying for, making time for, and succeeding in school. Students do not necessarily tell their instructors about the array of life challenges that they are facing, so it can be easy to misunderstand and misjudge underperformance. For many of these students, successful achievement means making hard choices when deciding what to focus on in their courses, perhaps attending to activities that allow them obtain passing grades and skipping those worth fewer points. For instance, a student may feel satisfied with a C grade because that is what they are able to achieve within their life circumstances. Online students are incredibly brave and motivated; they (and their families) make sacrifices large and small every day to pursue educational goals, and even small academic achievements (like passing a challenging course) can feel monumental for students when seen in the context of their competing responsibilities.

Instructors may become frustrated when students need additional flexibility or (informal) accommodations to continue in the course. A student who is stressed, tired, and hungry will also become frustrated if they find no support for or understanding of pathways to continue their coursework. If a student shares what is going on and what they need, our first reaction should be to be kind, demonstrating understanding and compassion. Showing kindness involves recognizing the humanity in students, thinking more intentionally about who they are, why they are in the course, what challenges they face, and believing them (Denial 2024). Believing students who come to you for help, having empathy, and recognizing that we can never assume we know what is going on in a person’s life can make a big difference, especially for students who have already made a financial, time, and emotional commitment to pursue their academic goals through online education. Online students really do have full, complex lives and are doing their utmost to take school on, too, to better their own lives and the lives of their families.

Scenario: James shares in an introductory course discussion board that he is part of the “sandwich generation,” meaning that he is taking care of his young children and his parents at the same time. James also discloses, to his instructor only, that he suspects he has a learning disability for which he never received a formal diagnosis because he did not have sufficient medical coverage to visit specialists that would provide testing and documentation. At midterm, James asks to drop out of the group project assignment and complete it independently because his group members have stopped engaging with him, and he thinks it is because of his disability. A few days later, he also asks for additional deadline flexibility because his father has been hospitalized.

Possible next steps: Trust in students and acknowledge the challenges they are facing, which may be one or many. Important considerations are to demonstrate care and empathy, provide some level of flexibility, such as offering an alternative assignment, allowing students to work independently if/when circumstances warrant it (such as in the case of James), or giving a reasonable extension on deadlines so that they can take care of whatever has come up for them and then return to focusing on coursework soon. The key is to think reasonably about what is possible. Students should still meet course outcomes, but there may be alternative paths to reaching them. Also, be ready to offer suggestions for additional resources that can help your students; most instructors are not trained counselors but will encounter students who need help and support beyond their training and credentials. Student services staff are often helpful experts on what resources are available to online students, current wait times, or restrictions for accessing services, so that you can provide your students with accurate information.

Teaching Behaviors That Create Barriers to Online Student Success

In this section, we turn to a discussion of two specific teaching behaviors that can create barriers to success for online students. These behaviors are not necessarily related to any particular oversight about online students or their needs, but they are easy to fall into because of the asynchronous nature of the modality and the high workload of most online instructors. If you have inadvertently used any of these approaches previously, you are not alone. Our intention in this chapter is to raise your awareness of how these behaviors ultimately affect online students and to encourage you to think about alternatives to better support their learning and success.

Appearing Unapproachable

From a student’s perspective, getting to know an instructor in any modality may not feel inherently easy or even appropriate. Academia has long perpetuated a hierarchy that puts novice students at the bottom and creates distance between them and instructional faculty, with instructors always wielding the power of grades (and recommendation letters). But in an online class, that relationship between instructor and student can be further obscured by asynchronous and often text-heavy communication that itself creates distance and a sense of impersonality.

That distance can be compounded by instructors who have, even unintentionally, positioned themselves as unapproachable. Students may perceive an instructor to be unapproachable not necessarily from any one particular event or message, but from a buildup of signals (or a lack of communication generally) that suggest that the instructor has other, more important priorities than teaching the course and is generally too busy to attend to students’ learning needs, answer their questions, or help them be successful. An instructor biography that describes the global reach of their research might sound appealing at the outset, but such messaging, compounded by a slow turnaround time on email questions and conversations, can easily lead to a perception that the instructor prioritizes their research over the online course. An announcement posted with the aim of being transparent that assignment feedback will take a little longer than planned can also contribute to the perception of unapproachability. “I have been working on a research proposal,” “I have been away at a conference,” and “I am submitting my book manuscript” are all reasonable justifications for a delayed timeline, but such statements also emphasize the kind of activities the instructional faculty member is prioritizing over students who are waiting for feedback they can apply to their next assignment. A lack of information about how and when to reach out for assistance—particularly around the topic of office hours—can also suggest that the instructor is not really there to support students. Conversely, being transparent with students about when your high workload interferes with grading or feedback can help you build rapport with your students if you approach that message carefully, and with a clear indication that you want to take the time to give them helpful comments as soon as you can. (We will address this nuance further in chap. 4.)

It is hard to fault students for feeling vulnerable and uncomfortable about reaching out to an instructor whom they may well have never met in person, or even on a video or phone call. When a student is in distress, it will be that much harder for them to reach out if they are concerned that their instructor will respond negatively or may not respond at all. Imagine the consequences that can arise if the student chooses not to take the risk to reach out. There may be missed opportunities to help students who could have been reengaged with individualized support. Perhaps these students could have continued on in the class rather than withdrawn, passed the class rather than failed, or remained in the major rather than switching to another. In chapter 3, we will return to the concept of “instructor presence” that comes from socioconstructivism and the Community of Inquiry theory (discussed in chap. 1) to address considerations for creating and sustaining presence imbued with warmth and approachability. Approachability also has a dimension of care that is much more than just showing up—it means communicating openly and genuinely to students that “Your questions or concerns are worthy of my attention, and I will make time for you.”

Ghost or Shadow Instruction

The sense of immediacy in the online environment is elusive, and many students wonder if their instructors are working alongside them at all. Commonly referred to as “ghost” or “shadow” instruction, it refers to a seemingly absent instructor: one who does not participate in discussion forums, who may irregularly respond to student emails and messages, who takes a week or more to return grades and feedback on assignments, and who rarely use communication tools (e.g., announcements, messages) or other features to interact with the full group of students.

Students may feel like an online course has been left to run on its own because they hardly ever hear from their instructor. Most students genuinely want to learn from the subject matter expert about whether they are on the right track with their answer or a line of thinking or a project. Discussions in particular can feel awkward to students without an instructor actively facilitating them. In Ecampus instructor training, we use the analogy that no (engaged) teacher would ever walk into an on-campus course, write a discussion question on the board, say “discuss, good luck!” and exit the classroom—and yet online students may feel that sense of abandonment whenever they are left to chat only among their peers on the learning management system (LMS) discussion board. Students are eager to know what is going well and what is not, and they will look to the instructor to help gauge and guide their learning during the term. If that guidance and feedback are not available, students may even feel less motivated to participate fully in the course, knowing that their learning experience is already diminished.

Of course, it is possible that a seemingly absent instructor is actually looking through the student discussion posts, skimming submitted assignments to determine what kind of feedback will be needed, managing a high volume of emails by only responding quickly to urgent student requests, and more. But these efforts are invisible to students if there is no concrete engagement. Students could perceive that their instructor is not paying much attention to the course and may not be invested in their success.

Instructors may also undervalue their own facilitation contributions, especially in a robust online course where it can feel like the whole course experience is already available to students in the LMS. If the course was not intentionally designed to be self-paced or automated, however, there will be a true need for thoughtful and engaged facilitation, not to mention that instructor interaction is required if the course or program is subject to the US Department of Education’s “regular and substantive interaction” policy.[1] Students value their instructor’s presence, availability, and willingness to help (Dennen et al. 2007) as well as their instructor’s interactions through feedback, discussion posts, and responses to questions (Ley and Gannon-Cook 2014). Instructor interactions can motivate students and support learning; conversely, students can be demotivated and isolated by ghost or shadow instruction.

Reflection and Action

This chapter addressed common oversights about online students that lead to learning barriers as well as two teaching behaviors that can negatively affect online student success. We invite you to take some time to think about how you can connect more intentionally with and continue to learn more about your online students. Doing so can help you guard against falling into the types of online teaching behaviors that impede student success. With the foundation of this awareness-building and reflection work, the next three chapters explicitly address practical and applied inclusive teaching strategies to advance student success.

You Might Be Ready to . . .

- Take an inventory about what you know about your online students from data that you have access to at your own institution.

- Find out more about the challenges your online students commonly face. Academic advisors and student success staff often know this information and are eager to share their insights with instructors.

- Consider how to actively work against the perception of unapproachability and ghost instruction.

Questions for Further Consideration

- Which oversight were you most familiar with? How did you discover that it was untrue?

- Which oversight were you least familiar with?

- Are there any other oversights that you have heard (or had) about your online students that you (now) know to be incorrect, whether partially or wholly?

References

Balgopal, Meena M., Anne Marie A. Casper, Alison M. Wallace, Paul J. Laybourn, and Ellen Brisch. 2018. “Writing Matters: Writing-to-Learn Activities Increase Undergraduate Performance in Cell Biology.” Bioscience 68 (6): 445-54. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biy042.

Casareno, Alexander B. 2010. “When Reading in College Is a Problem: What Really Matters?” In Teaching Inclusively in Higher Education, edited by Moira A. Fallon and Susan C. Brown, 39-60. Information Age.

CAST. 2025. “Universal Design for Learning Guidelines 3.0.” Accessed October 7, 2024. https://udlguidelines.cast.org.

Decker, Jessica, and Valerie Beltran. 2016. “Students’ Sense of Belonging in Online Classes: Does Age Matter?” International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design 6 (3): 14-25. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijopcd.2016070102.

Dello Stritto, Mary Ellen, and Kathryn E. Linder. 2018. Student Device Preferences for Online Course Access and Multimedia Learning. Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit. https://ecampus.oregonstate.edu/research/study/student-device-preferences/student-device-preferences-study.pdf.

Denial, Catherine J. 2024. A Pedagogy of Kindness. University of Oklahoma Press.

Dennen, Vanessa P., A. Aubteen Darabi, and Linda J. Smith. 2007. “Instructor–Learner Interaction in Online Courses: The Relative Perceived Importance of Particular Instructor Actions on Performance and Satisfaction.” Distance Education 28 (1): 65-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2007.10782499.

Essien, Idara, and J. Luke Wood. 2022. “Suspected, Surveilled, Singled-Out, and Sentenced: An Assumption of Criminality for Black Males in Early Learning.” Journal of Negro Education 91 (1): 65-82. muse.jhu.edu/article/862073.

Federal Communications Commission. 2024. “Statement of Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel.” March 14, 2024.” https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-24-27A2.pdf.

Griffin, June. 2018. “Writing-Intensive Classes.” In High-Impact Practices in Online Education: Research and Best Practices, edited by Kathryn E. Linder and Chrysanthemum Mattison Hayes. Stylus.

Henrikson, Robin, and Nalline Baliram. 2023. “Examining Voice and Choice in Online Learning.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 20 (31): 1-19. https://educationaltechnologyjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41239-023-00401-w.

Hewett, Beth. 2015. Reading to Learn and Writing to Teach: Literacy Strategies for Online Writing Instruction. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Kara, Mehmet, Fatih Erdogdu, Mehmet Kokoç, and Kursat Cagiltay. 2019. “Challenges Faced by Adult Learners in Online Distance Education: A Literature Review.” Open Praxis 11 (1): 5-22. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.1.929.

Ke, Fengfeng, and Alicia Fedelina Chávez. 2013. Web-Based Teaching and Learning across Culture and Age. Springer.

Ke, Fengfeng, and Kui Xie. 2009. “Toward Deep Learning for Adult Students in Online Courses.” The Internet and Higher Education 12 (3-4): 136-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.08.001.

Klein, Perry D., Nina Arcon, and Samanta Baker. 2016. “Writing to Learn.” In Handbook of Writing Research, 2nd ed., edited by Charles A. MacArthur, Steven Graham, and Jill Fitzgerald. Guilford Press.

Långstedt, Johnny. 2018. “Culture, an Excuse?—A Critical Analysis of Essentialist Assumptions in Cross-Cultural Management Research and Practice.” International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 18 (3): 293-308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595818793449.

Lapadat, Judith C. 2002. “Written Interaction: A Key Component in Online Learning.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 7 (4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00158.x.

Ley, Kathryn, and Ruth Gannon-Cook.2014. “Learner-Valued Interactions: Research into Practice.” Quarterly Review of Distance Education 15 (1). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED546877.pdf#page=113 .

Martinez, Christy Teranishi, Ned Kock, and Jeffrey Cass. 2011. “Pain and Pleasure in Short Essay Writing: Factors Predicting University Students’ Writing Anxiety and Writing Self‐Efficacy.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 54 (5): 351-60. https://doi.org/10.1598/jaal.54.5.5.

Marzano, Robert J., Debra J. Pickering, and Tammy Heflebower. 2011. The Highly Engaged Classroom. Marzano Research.

Mazur, Eric. 2009. “Farewell, Lecture?” Science 323 (2): 50-51. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1168927.

Messineo, Melinda. 2018. “The Science of Learning in a Social Science Context.” In Learning from Each Other: Refining the Practice of Teaching in Higher Education, edited by Michele Lee Kozimor-King and Jeffrey Chin. University of California Press.

Moore, Emily. 2021. “Six Ways Text Can Make (or Break) Effective Online Course Design.” Faculty Focus, July 9, 2021. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/online-course-design-and-preparation/six-ways-text-can-make-or-break-effective-online-course-design/.

Moule, Jean. 2012. Cultural Competence: A Primer for Educators. 2nd ed. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Nisbett, Richard E., Kaiping Peng, Incheol Choi, and Ara Norenzayan. 2001. “Culture and Systems of Thought: Holistic versus Analytic Cognition.” Psychological Review 108 (2): 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291.

Payne, Taylor, Katherine Muenks, and Enrique Aguayo. 2023. “‘Just Because I Am First Gen Doesn’t Mean I’m Not Asking for Help’: A Thematic Analysis of First-Generation College Students’ Academic Help-Seeking Behaviors.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 16 (6): 792-803. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000382.

Puzziferro, Maria, and Kaye Shelton. 2009. “Challenging Our Assumptions about Online Learning: A Vision for the Next Generation of Online Higher Education.” Distance Learning 6 (4): 9. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/challenging-our-assumptions-about-online-learning/docview/230731994/se-2.

Racek, Brittni. 2020. “Reasons Online Students Hesitate to Reach Out to Instructors.” Presented at Ecampus Teaching Online-Pedagogy Seminars (TOPS), Corvallis, OR, February 5.

Riggs, Shannon. 2022. “Update the GI Bill for the Online Era.” Progressive Magazine, November 11, 2022. https://progressive.org/op-eds/update-the-gi-bill-riggs-221111/.

Safford, Kimberly, and Jane Stinton. 2016. “Barriers to Blended Digital Distance Vocational Learning for Non‐Traditional Students.” British Journal of Educational Technology 47 (1): 135-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12222.

Salmon, Gilly, Bella Ross, Ekaterina Pechenkina, and Anne-Marie Chase. 2015. “The Space for Social Media in Structured Online Learning.” Research in Learning Technology 23. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v23.28507.

Shapiro, Shawna, and Laura Aull. 2023. “Plain Language Is Key to DEI in Academe.” Inside Higher Ed, October 13, 2023. https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2023/10/13/plain-language-key-dei-academe-opinion.

Simunich, Bethany, Racheal Brooks, and Amy M. Grincewicz. 2023. “Centering Learner Agency and Empowerment: Promoting Voice and Choice in Online Courses.” In Toward Inclusive Learning Design: Social Justice, Equity, and Community, edited by Brad Hokanson, Marisa Exter, Matthew M. Schmidt, and Andrew A. Tawfik, 457-66. Springer Nature Switzerland.

Slover, Ed, and Jean Mandernach. 2018. “Beyond Online versus Face-to-Face Comparisons: The Interaction of Student Age and Mode of Instruction on Academic Achievement.” Journal of Educators Online 15 (1): n1. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1168945.pdf.

Stephen, Jacqueline S. 2023. “Persistence of Nontraditional Undergraduate Online Students: Towards a Contemporary Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Adult and Continuing Education 29 (2): 438-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/14779714221142.

Tereshko, Lisa, Mary Jane Weiss, Samantha Cross, and Linda Neang. 2024. “Culturally Diverse Student Engagement in Online Higher Education: A Review.” Journal of Behavioral Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-024-09554-8.

WCET. 2021. “Regular and Substantive Interaction Refresh: Reviewing and Sharing Our Best Interpretation of Current Guidance and Requirements.” August 26, 2021. https://wcet.wiche.edu/frontiers/2021/08/26/rsi-refresh-sharing-our-best-interpretation-guidance-requirements/.

Wildavsky, Ben. 2021. Meeting the Needs of Working Adult Learners. Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. and Guild Education. https://connect.chronicle.com/rs/931-EKA-218/images/ServingPostTraditionalStudents_GuildEducation.pdf.

- For an overview of regular and substantive interaction (RSI) and its current interpretations, see WCET (2021). ↵