4 The Inclusive Online Facilitation Tool Kit

Introduction

As discussed in chapter 3, instructor presence is an incredibly important factor in online student motivation and success, and it counters the issues of “ghost instruction” that we addressed as a barrier for online students in chapter 2. Just like students taking courses in other modalities, online students want to belong and connect to a learning community, and the instructor is an impactful leader and influence in that community. The presence that an instructor builds and demonstrates across a course must be tangible, though; in most learning management systems (LMSs), students cannot “see” when their instructor (or their peers) are online, though this is possible if the course uses an LMS-based or external chat feature (e.g., Microsoft Teams or Slack). Without discrete interactions posted with a timestamp, such as announcements, messages, and assignment feedback, an instructor may be reading along as the students progress through assignments, but that activity is invisible to students. The key to fostering presence in an online classroom is to develop a plan for how to demonstrate that you are “showing up” in your online class. By selecting engagement strategies best suited to your teaching style, you will help motivate and encourage students like Carla to stay engaged and complete the course (and, hopefully, their program).

In this chapter, we offer a “tool kit” of practical inclusive teaching strategies that lean into different kinds of instructor presence and that correspond to the ways student needs may shift over the course of an academic term. These strategies are supported by research, by experience, and by instructor alumni from our workshop, and emphasize planned, proactive approaches; excellent online teaching rarely happens when interaction with students is left to chance. We discuss course facilitation strategies here since most online instructors in higher education have a good deal of freedom to make strategic choices that serve their students, even if they did not create or cannot amend the design of their course. We address discussion facilitation separately in chapter 5 because it is such a core form of interaction with all students in online courses and deserves additional consideration and elaboration because of its complexity.

Make Connections with and for Students Using Announcements

One of the easiest ways to demonstrate instructor presence and also do meaningful teaching in an online course is to use announcements in multiple ways for maximum impact. The LMS announcement feature is most commonly used for pushing out logistical information (e.g., an upcoming exam reminder or a note that an assignment deadline has been extended), but announcements can be used for many other reasons, including helping students to make connections within and beyond the course.

Online courses may be partially or fully missing the narrative that commonly weaves together parts of an in-person course. During course meetings on campus, instructors “tell the story” of how one piece of content connects to an activity and then is furthered with an assessment next week, or they may share personal anecdotes or experiences that create an important sense of presence and connection (Gordon 2017, 103-4). Yet the discrete items and pages of an online course sometimes fail to draw out those connections for students or do not leave space for the kind of narrative that can help to “structure our thinking” (Hokanson et al. 2017, v). Announcements can fill in those gaps in ways that can guide students through the course and clarify the purpose and connection between various parts or to real-world contexts, ultimately providing students with a greater sense of context and meaning in the course. They are also one of the primary ways to visibly indicate that you are tracking what is going on and engaging in the course.

A growing body of research makes the case for the instructor’s role in helping students make connections and meaning in the course to foster student motivation, specifically intrinsic motivation (Wlodkowski 1999; Merriam and Bierema 2013; Henning and Manalo 2014; Kember 2016; Miller 2021). Students should be able to understand why they need to take the course for their program in introductory course information, but much of the meaning-making and connection-building can happen within the course as well and with the instructor (Pritts 2020). Kember’s (2016) framework of eight themes that motivate or demotivate students in the teaching and learning environment includes two themes relevant to the use of effective announcements in online classes: establishing relevance of the material (for students’ lives) and teaching for understanding (rather than rote learning). Adult students who may be pursuing higher education as a means of career advancement will also benefit from connections between course content and real-world applications, as well as skills developed in the course and their relationship to potential careers.

Announcements can play many roles through a course, including but not limited to the following examples that emphasize contextualization and making meaning:

- Welcome students to the course by talking about its relevance (in the program, to career paths, to answering or solving timely questions in the world).

- Create a “bridge” between each week or unit by highlighting the connections or divergences between them.

- Share key takeaways from small group discussions, especially when students cannot see other groups’ forums.

- Feature relevant stories or examples from the news.

- Provide high-level feedback summaries from assignments, emphasizing the relevance to look at for upcoming assignments.

- Highlight and praise good work (e.g., “Make sure you look at Latisha’s excellent example in last week’s discussion of how she put X into practice at work!”) that has advanced learning in the course.

- Share any updates or changes made to deadlines based on how students are progressing.

- Provide encouragement during periods that are typically most challenging for students (e.g., midterms, finals, during high-stakes projects) by emphasizing what is to be gained, when there will next be a bit of a “break,” or if you are offering additional supports, like extended office hours.

Used judiciously, creative announcements can also help lighten the tone of a course, particularly in classes that are especially challenging, heavy on emotionally sensitive content, or written in a formal tone (i.e., in third person). Announcements need not be perfect, particularly if you are considering doing them in a video (though be sure to add accurate captions). Katherine’s most successful video announcements featured unexpected appearances from her golden retriever, who suddenly became something of a mascot for correct use of American Psychological Association (APA) style and citation in a research writing course where most students self-identified as having writing anxiety.

Announcements should be used thoughtfully and to maximize relevance to that particular group of students; online students are astute critics and can spot text that has been used term after term, and they notice when announcements are set to post at the exact same time every week. Announcements also should not be overused, since too many communications get overwhelming for students, particularly if they are enrolled in more than one class at a time. It is a good idea to communicate to students at the beginning of the course how you plan to use announcements and about how often they should expect to see them so that students can adjust their LMS notification settings if needed. (Helping your students to develop the habit of checking course announcements and providing a value add in those communications will lessen the risk that this information goes unnoticed or unused.)

Ask Students about Themselves

If you have taught in any modality before, you know that every group of students is different, both in terms of the class as a whole (its dynamics, willingness or reticence to deeply engage, etc.) and in terms of its individual members. Even an online course that is relatively rigid in terms of its structure—including predesigned courses that you cannot edit—can be flexible in terms of how you interact with and support your students. Instructors who teach in cohort models, where students take courses together in the same order, have an advantage if they have taught the group before or if they can glean insight from colleagues who have taught the group already. But the reality is that you may go into teaching an online course knowing little about your students. Your institution’s student information system (SIS) may give you basic details such as a student’s full name, preferred name, pronouns, major, year in school, and home address. This information is not much to work from, though, and gives you a limited picture of that student and what their needs might be, which can lead to the oversights we discussed in chapter 2. For that reason, it is critical to familiarize yourself with any information you can gather about your students and then think about what additional information you want and need.

Most online courses have an introductions discussion forum of some type; it is considered a best practice in online education[1] to use such a forum to allow students to introduce themselves, and research has shown that learners feel a stronger sense of belonging when they have an opportunity to get to know their peers (Shea 2024, 75). Prompts in this kind of forum can vary widely, so you will want to think creatively about what to ask. If you can add or alter the questions in your course’s forum, you might consider not just interesting questions that help students’ preferences and personalities to emerge (e.g., What is something that you enjoy doing outside of school?) but also questions that help students share relevant information with peers and with you (e.g., Do you have expertise or experience in any topics covered in this course?). It is also a best practice to respond individually to each student in this forum, which might also influence the kinds of questions that you ask so that you can be sure to follow up in meaningful ways. Great questions for introduction forums include the following examples.

- French film course: What is your favorite French-language film, and why?

- Soil science course: How would you describe the soil you would find if you started digging in your yard or somewhere in your local community?

- Math course: When was the last time you worked on calculations personally or with your family? What tools or strategies did you use to complete the calculation?

- Business course: What is an example of great small business leadership that you have seen, experienced, or heard about?

- Any course: What is one characteristic of a great online course, and how can we foster that together this term?

As you think about what you want to have students share, consider what they may be willing to share in the public forum (to the whole course) at the beginning of a term, particularly if they are unlikely to know you or their peers. Some students may be eager to share, and others may hesitate to do so until they get to know everyone in the class a little better. To this point, remember that there may be cases where students cannot reveal personal information, such as where they are located (students with personal privacy concerns, students who are deployed in the military, etc.). You may want to divide your questions between the introductions discussion forum (just a few!) and a beginning-of-term survey that students submit only to you, and make particularly sensitive questions like location optional even when that is information shared only with you.

In addition to information collected through an introductions discussion, a beginning-of-term survey helps provide you with some initial details about each student that you can continue to expand and extend as you get to know them. In terms of content, think about an activity title and set of questions that will communicate your intention to connect with students without coming across as intrusive. In OSU Ecampus courses, we often call these surveys a “Who’s in the room?” survey and use a short set of three to five questions, tailored to the course in the sequence of a given program and adjusted for undergraduate/graduate level. Below we offer some of our sample questions, and Michelle Pacansky-Brock (2024) also offers helpful question ideas on her website.

- What would you like me to call you? (short answer)

- What are your pronouns? (short answer)

- Which of the following describes you? (select all that apply)

- This is my first year in college.

- I am the first in my family to attend college.

- This is my first time taking an online course.

- I work more than 20 hours per week.

- I am a caretaker for at least one other person.

- In one word, describe how you are feeling about this course. (short answer)

- Do you anticipate any parts of this course being especially challenging for you? (short answer)

- What are you most excited about in taking this course? (short answer)

- Do you have particular areas of expertise or examples related to this course that you would like to share with me as we begin? (short answer)

- At this time, what is your academic goal? Is there anything I can do this term to help you work toward that goal? (short answer)

- Is there anything you’d like to share or ask me at this point? (short answer)

It is a good idea to incentivize completion of this kind of survey (the credit can be nominal or even extra credit) and to frame it with information about why you include it. For example, you might include an introduction that communicates that you value each student’s perspective and that you want to address their concerns and attend to their needs as much as possible.

To deliver the survey, almost any basic web-based survey tool can work. Your institution’s LMS may have an integrated quiz or survey tool, or you may have access to another survey tool within your institution’s technology ecosystem (Google Forms, Qualtrics, etc.). If you use an external tool that is not located within your institution’s domain, be cautious about the kinds of data you are collecting from students, whether the data are being stored securely, and how the application or vendor may use and retain such data since you are deploying a survey where the student’s name will be associated with their information.

Ideally, whatever tool you use will produce a spreadsheet of information on your students. Print it out or save it locally (somewhere secure) so that you can reference and add to it throughout the term. Add columns or otherwise make notes as new information about that student comes to light, such as when you have approved an assignment extension; whether the student discloses a major life, medical, or family event that may interfere with their progress in the course; when they ask for additional support in a particular area of the course; and so on. Initial information for all students is helpful as a reference, but additional information may only be needed for some students. Table 4.1 shows what a sample spreadsheet might look like.

| Student Name | Preferred Name | Pronouns | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adams, Susan |

Sue | she/her | Taking overload credits this term |

| Bendry, Jo |

Jo | they/them | Will be out of town for a business trip during week 8 so will be working ahead and possibly catching up afterward |

| Collins, Madelyn |

Maddie | she/her | Has writing anxiety and has asked for additional support with writing mechanics and style |

| Fischer, Milo |

Milo | he/him | Retaking the course |

| Shin, Yamato |

Yamato | he/him | New parent |

This information can then be used as you go: when you are responding to student emails, engaging in online discussions, providing feedback on graded work, and the like. For instance, in research writing courses that Katherine teaches, students often disclose varying levels of writing anxiety in the beginning-of-term survey. She uses that information to tailor her commentary to students who are most in need of growth mindset strategies (covered later in this chapter). If a student asked for specific coaching on grammar and mechanics—topics not explicitly covered in the class but are important fluencies that the student wants to continue practicing—then she notes that and can help guide the student in those areas during the term.

Given the large size of many online courses and the high teaching load for most instructors today, it is not reasonable to expect that our memories can hold all of the relevant information that we learn about our students and that they share with us, but this information is needed to support students most effectively by adding personal context. A helpful approach is to keep and use good notes on students, even if the information is just a few key points in a large-enrollment course. Teaching assistants in large-enrollment courses could also benefit from having some background information on each student to guide their interactions with them.

Implementing meaningful introduction spaces and a beginning-of-term survey help to demonstrate that you care about your students and want to get to know them from the very beginning of the course helps to build trust, rapport, and community online. Research on teaching methods that support men of color and first-generation students in community college settings has shown that emphasizing “relationships before pedagogy” is important, meaning that it is crucial to build relationships before students can fully engage with course content (Wood et al. 2015). This recommendation can extend to other populations and to teaching at four-year institutions. Michelle Pacansky-Brock (2024) notes:

Humanized online teaching leverages students’ lived experiences as the context of your curriculum. This involves intentionally designing a class that is built to ensure you know your students as real people and are prepared to utilize your knowledge of their lives to adapt your teaching and support their success. A Getting to Know You Survey in week one is an important part of fostering trust and laying the foundation for the instructor-student relationship you will leverage to challenge students and hold them all to the same high expectations. (para. 1)

Sometimes included as part of a “pedagogy of care,” this first gesture of getting to know each student as more than a name and profile photo on a screen helps students to feel comfortable so that they can focus on learning (Rider 2019; Waghid 2019).

Provide Transparent Assignment Directions

One of the key differences between online and on-campus courses is that online students cannot always get immediate clarification about course tasks, processes, or assignment requirements. In an on-campus class, instructors may “go over” an assignment by sharing the prompt, providing additional narrative or context about the assignment, and then taking questions. Conversely, online students only see the information that is included in the assignment prompt. Additional questions that come up for online students may require a visit during office hours or an email sent to the instructor or TA, and a reply may not come for hours or days. Online students are often so busy that they may not take the time to ask their questions and wait for a response; students may also hesitate to ask questions for fear of receiving a negative or dismissive response from their instructor (e.g., “You should go back and read the prompt”).

For these reasons, providing clear directions and transparency about how assignments will be evaluated is incredibly important to support online students. When creating new assignments in an online class, take a proactive approach, anticipating and answering potential questions so that the onus is not on students to ask. This strategy may reduce the number of questions that come by email later, which also saves you time. For assignments already in use, review the prompts and address questions that have come up in past offerings of the course to guide revisions, with the goal of continuing to hone clarity and transparency. If you are not able to modify assignments in the course you teach, you can share clarifications you identify based on the framework below in an announcement, for example.

Online course assignment prompts can usually be improved in some way. The structure of assignments may reflect a prominent focus on the “what” and the “how” of the assignment instead of a clear “why.” Look for places where the task instructions take the place of the purpose of the assignment; for example, an assignment might require students to complete a preliminary research report, with the stated purpose being to “complete the report in preparation for the presentation.” Providing a clear explanation of the purpose of the assignment helps students know what skills they will practice and what knowledge they will gain from completing that assignment. This approach will not only help them recognize achievement of the expected learning outcomes but can also provide motivation if they see the relevance of the assignment to their needs and interests beyond the course. Clarity also involves providing explicit descriptions of grading criteria and how performance will be assessed. Grading information should articulate the relative weight of each measure of performance (or criteria) so that students who are pressed for time can make informed decisions about where they should concentrate their efforts.

The Transparent Assignment Design (TAD) framework provides a helpful structure for ensuring key information is consistently articulated and presented to students (TILT Higher Ed 2024). It involves three sections for each graded assignment (but could be modified for ungraded assignments as well):

- Purpose: What is the bigger picture informing why students are doing this assignment? Does it connect to other parts of the class? What in the future (class, career, etc.) is it preparing them for?

- Task: What is the task? How should it be accomplished?

- Grading Criteria: How will the assignment be evaluated?

The Purpose section can be challenging to explain; one way to help answer the questions above is to consider the question, “Why are students doing this assignment and not some other assignment?” For example, you might have chosen a 10-page research paper as the summative assignment in the course—but why an essay format, and why that exact length? If that question is not easy to answer, then there may be an alignment problem; perhaps the assignment is not really set up to meet a particular course outcome. Alternatively, the assignment may narrowly prescribe a form of demonstrating learning, or it is not constructed in a way that makes it a purposeful step toward something else in the current course, another course, the program, or a career.

Generally speaking, the Task section is the easiest to fully explain as the set of steps a student must complete sequentially. Online students can get stuck on process elements, however. For example, if an assignment requires use of a technology tool—say, a collaborative editing tool, a mind mapping app, or a video editor—some additional detail may be necessary. Specific instructions on how to access and use that tool should be offered, as well as information about where to access technical support as needed. An assignment that allows students to choose from any number of tools might provide a few examples (ideally of free, low-cost, or institution-supported tools) with resources and technical support information. Providing this information up front helps students to avoid getting hung up on the use of the tools and allows them to focus on the learning process and product instead.

Finally, a sufficient description of the Grading Criteria and performance evaluation provide students with the information they need before completing the work. Providing a full rubric or grading guidelines that references criteria and performance levels is ideal. The rubric can then be used in the grading process to help students see where they did well and where they have additional work to do. (We address rubrics and feedback in more detail later in this chapter.) But whether or not rubrics are used as part of the scoring process, consider if you are using certain grading practices simply because they have been traditionally used in higher education; not all methods serve students from different backgrounds and with varied abilities (Denial 2024). Rubrics or detailed grading criteria are good examples of how to communicate expectations more transparently for students, but there are many other ways to emphasize equity in grading practices (see Artze-Vega et al. 2023).

Here is an example of an initial prompt (from a real course, but adapted to ensure anonymity) and an improved version using the TAD framework.

Initial Prompt

This week, you will submit the draft of your project report for peer review. Each of you will provide feedback on one of your peer’s papers, addressing the following aspects:

- Identify the strengths of the arguments (e.g., comment on how well the game-based learning framework supports the evidence of the case, how the examples support the details of the case).

- Identify areas in which the paper needs improvement, and give suggestions on how to improve it.

- Comment on how the writer connects each aspect of the case to the chapter on motivation and technology.

- Comment on the clarity and writing of the paper. Give suggestions for improvement.

- Check the writer’s citations and references for any mistakes or typos, and suggest any needed corrections.

Revised Prompt

Purpose

The purpose of this assignment is to engage you in a critical analysis of arguments, allowing you to identify how the writer makes connections in their research report with respect to the primary and secondary characteristics of the GBL framework. By engaging in this peer-review assignment, you will also identify and employ strategies to improve your academic writing and offer constructive feedback, while also thinking about how your writing choices connect to your audience.

Task

This peer-review assignment will consist of the following steps:

- Access the peer review in this Canvas assignment page by selecting Peer Reviews on the menu that appears on the right-hand side of the page.

- Use the text editor tools to do the review (i.e., highlight relevant ideas, provide comments on specific sections of the paper, cross out potential areas to remove, and so on), with the following focuses:

- Identify areas where the paper is doing something well.

- Identify areas where the paper needs improvement, and give suggestions on how to improve it.

- Check the writer’s citations and references.

- Note errors that interfere with meaning, and suggest any needed corrections.

- Then, submit a short paragraph in the box labeled Add a Comment, identifying:

- The major strength and weakness of the paper.

- A brief summary of how the writer connects each aspect of the case to the chapter on motivation and technology.

Criteria for Success and Grading Rubric

Because the purpose of this assignment is to engage in critical analysis, a successful peer review assignment should involve inquiring about assumptions being made by the author, decentering ourselves from the focus of review to avoid instilling our own views, recognizing and valuing others’ perspectives, and fact-finding that supports arguments. Success in this assignment is in essence a constructive dialogue between authors and reviewers to ensure quality of the research report. This assignment will be graded over 10 points and based on the following criteria:

- Critical analysis: 2 points

- Constructive feedback: 2 points

- Clarity and organization of suggestions: 2 points

- Respectful and supportive tone: 2 points

- Summary: 2 points

- See the Peer Review Rubric for specific details on the grading criteria.

In one major American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) study, led by Winkelmes et al. (2016), faculty revised two take-home assignments (from on-campus courses) to increase their transparency and relevance for students. This study included 1,800 students and 35 faculty from a varied group of higher education institutions and yielded extremely positive results. The improvements in learning outcomes with transparently designed assignments were statistically significant for all students and so apparent to faculty in the midst of the study that they struggled to keep the protocol out of their “control” courses and to limit their intervention to just two assignments. Importantly, however, “for first-generation, low-income, and underrepresented students, the observed benefits were larger. First-generation and multi-racial students experienced medium-to-large effect size differences in the three domains that are critical predictors of students’ success: academic confidence, belonging, and mastery of skills that employers value” (Winkelmes et al. 2016, 33). Faculty surveyed as part of this study also noticed additional benefits that were not specifically being evaluated, such as increases in student motivation, more focused and higher-level class discussions, more on-time completion of assignments, and fewer grade disputes (Winkelmes et al. 2015). Adult learners specifically are more likely to be motivated to complete assignments where they can clearly see the relevance to their goals and the assignment’s relatedness to outcomes of the class (Sogunro 2015), and assignment transparency helps reveal these connections and improve student motivation. Howard et al. (2020) then tested how the TAD model works in online courses in a quasi-experimental study and found that transparency can help mitigate the challenges that students face in online learning.

Clear assignment structure can also support neurodivergent learners who may struggle with executive functioning skills needed to initiate or complete tasks. Providing these students with well-structured assignments that include clear guidelines, a step-by-step process, and expectations for a successful outcome can help them focus on the tasks, reduce their anxiety, and maximize their learning (Knight 2022).

Reach Out to Disengaged and Struggling Students

When teaching an online course, it can be easy to fall into the trap of assuming that a student is unmotivated or is just disengaged when there are actually other things going on in their lives. With learners who are juggling personal, work, and school commitments, there may actually be multiple challenges preventing them from engaging (or fully engaging) in their coursework even though they want to do so. In this section, we suggest two different types of strategies for approaching disengaged and struggling students: those that can be anticipated and made before the term begins and those that can be made during the term.

Before-the-Term Strategies

The strategies below can be implemented before the term begins to help prevent common barriers that arise for busy online students.

Articulate the Time Commitment and Support Time Management

The reasons that students offer for why they have been unsuccessful in online courses provide some insight into how instructors can better support students. After surveying students who withdrew from or earned a failing grade in online courses, Fetzner (2013) reported on the top 10 reasons why students say they were not successful in their online course (table 4.2).

| Reason | Percentage of Students Indicating |

|---|---|

| I got behind and it was too hard to catch up. | 19.7 |

| I had personal problems (health, job, child care). | 14.2 |

| I couldn’t handle combined study plus work or family responsibilities. | 13.7 |

| I didn’t like the online format. | 7.3 |

| I didn’t like the instructor’s teaching style. | 7.3 |

| I experienced too many technical difficulties. | 6.8 |

| The course was taking too much time. | 6.2 |

| I lacked motivation. | 5.0 |

| I signed up for too many courses and had to cut down on my course load. | 4.3 |

| The course was too difficult. | 3.0 |

An important finding in this study is that online students infrequently respond that the course is too difficult or that they lack motivation. Rather, two of the three most prevalent responses (“I got behind and it was too hard to catch up” and “I couldn’t handle the combined study plus work or family responsibilities”) indicate that students often experience time-related pressures outside of school that cause them to withdraw or fail a course.

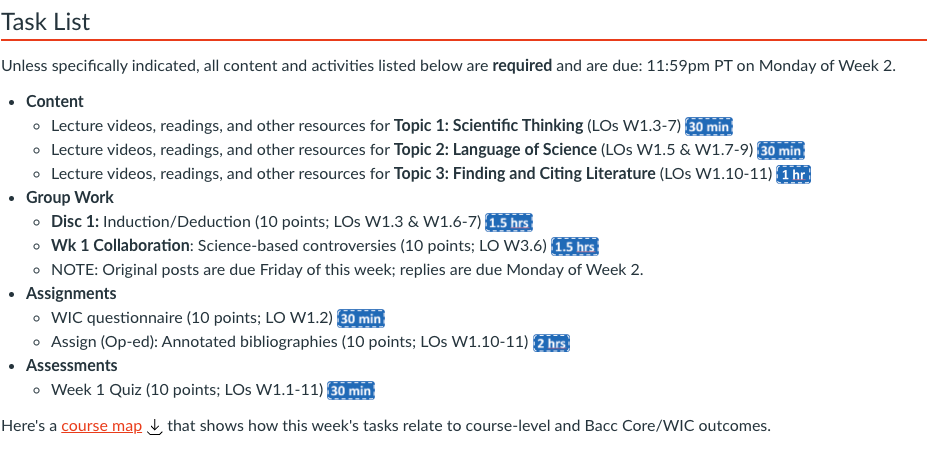

Where instructors have the greatest opportunity to make a difference for these students (and tend to already be successful in online courses) is in being explicit and transparent about the time commitment that the course will require. For example, including estimates for how long each week’s individual tasks will take can help students better plan out their time, giving them a sense of when a task is taking too long and they should perhaps reach out for assistance. This approach may take the form of a study plan (fig. 4.1) that students fill out and submit to you, or a detailed list of weekly tasks, each with the estimated time for completion (fig. 4.2). One or both could be embedded in an LMS assignment or instructional pages of a course where instructors have the ability to modify their own course site; instructors who cannot edit their courses could share these items with students and describe how to use them in announcements.

Helping students to plan out and manage their time during a course will not prevent students from withdrawing or from failing a course. The withdrawal process is a critical option for students who took on too many courses, who have other significant things happening in their lives, or who need to protect their grade point average. It is essential to not stigmatize the withdrawal process but to provide pathways to support students who are stretched for time. Be supportive by encouraging them to come back and take the course again when they are able.

Add Supplemental and Refresher Materials

Sometimes, online students get behind on an online course because they are trying to learn concepts that instructors assume they know coming into a course when, in reality, they may not have that foundation yet or they may not have retained the information since they took a prerequisite course. Think of the student who has “stopped out” (taken time away from school) for a few terms or even a few years and is now returning to finish their degree, or the student who has transferred credits from another institution and so has not had continuity in their lower-division and preparatory course sequences.

To assist students who need to brush up on prerequisite content and skills before they can successfully complete work for your class, consider adding free resources from reputable sources (Khan Academy, university faculty on YouTube, etc.). Talk to colleagues in your department who teach courses that precede yours; you might also collaborate on pulling in content from their courses as refresher material where possible. This proactive work aligns to socioconstructivist approaches discussed in chapter 1 in that students can refresh foundational concepts and then build upon them in your classroom community.

Refresher material is ideally accessible directly from the course site without students needing to request access. Remember, students may not feel comfortable disclosing their lack of prerequisite knowledge and so may not ask for additional support. This material could be placed alongside weekly learning materials, collected in an additional refresher unit or module within the course, or offered in something as simple as a Word document that is shared with students in the syllabus or in a course announcement.

When instructors are teaching new (or new-to-them) online courses, knowing where refresher materials may be needed can be more challenging. Consider sharing resources proactively as you work through each module with your students; timely resource-sharing is an effective teaching method demonstrating your commitment to your students’ learning progress, helping them fill in the gaps.

Create Flexibility Where Possible with Due Dates and Late-Work Policies

Being mindful about the stress that students might be under during your class due to tight timelines and multiple competing priorities can help you craft policies that will support student success in your course. Research has shown that cortisol, often called the “stress hormone,” can heighten attention and focus when it is moderately present, but too much cortisol can actually impede learning because students lose the ability to determine what is important in the learning environment (Messineo 2018, 14). Perhaps even more importantly, reconsidering what deadlines represent in a course and how it really is possible to build in flexibility is an important act of “humanizing” online education (Rognlie et al. 2025).

Wherever you have control of course policies such as weekly deadlines, keep busy students in mind as you plan out which days assignments are due so that they have a reasonable chance to keep up. For example, allowing students at least one weekend day to work on homework assignments or weekly projects can support those students who are working and who may also have significant family responsibilities on weekdays. You could, for example, move a Friday at 11:59 p.m. deadline to the end of the day on Sunday. Providing as much flexibility as you can up front will help your students to fit school into their busy lives—and you might receive fewer emails with extension requests.

We know that busy adult students who use weekend days to work on course activities are likely to have and raise questions as they are working, and that creates pressure for instructors to be responsive on weekends. OSU Ecampus instructors who want to have screen-free time over the weekend have found a good compromise by pushing routine deadlines to Monday at 11:59 p.m. They make a commitment to students to answer all urgent questions on Monday morning, and then students have the remainder of that day to submit their work.

As we mentioned briefly in chapter 2, late-work policies can also create a barrier for students who need maximum reasonable flexibility in their coursework. In annual student surveys, OSU Ecampus students report that they struggle with courses where instructors have a policy of not accepting any late work. For these students, it is critical to have an option to turn in something late, even with a grade reduction, as a result of a work, family, or personal emergency. Consider revising your policy to allow for limited late submissions, such as up to three days late with a 10% score reduction for each day past the deadline. Some instructors have been successful in providing one or two “no questions asked” late-work passes to each student. Students can send an email, fill out a form, or submit a preliminary document in the LMS with a note indicating that they are using their pass for additional days to work on the assignment (the number of days varies by instructor and course, but a three-day pass is common). Instructors or their teaching assistants can track these late passes for students relatively easily, even in large-enrollment courses, and students benefit from built-in flexibility that does not require them to explain the situation that they are facing.

Allowing a certain degree of flexibility without asking for justification can also free you up from having to play judge and jury about student reasons for late work. For many instructors, this is an uncomfortable position anyway: it is difficult to make a determination about whose reasons are true or better or more justified, particularly with health-related concerns, where it is inadvisable to request supporting documentation that discloses any specific medical information (e.g., for compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, in the United States). Adult students may be facing any number of life circumstances affecting themselves or their families; they may have to choose between submitting homework on time and caring for an ill child or a disabled parent who lives with them. When online course policies include built-in flexibility, students can use their allowed extensions without needing to share any uncomfortable details.

To be clear, we are not advocating for extending limitless flexibility in your courses. Students who repeatedly ask for extensions may be more prone to take an incomplete in the course, which is sometimes a valid option for students but also has implications for their degree progress, financial aid, and more. Instructors may not be able to extend flexibility within or beyond the current term without implications for their own workload. But there is a middle ground with more generous course policies that remove barriers for students and allow them a reasonable extra time for taking care of the many important priorities that they are juggling, including but not exclusive to school.

We are sometimes asked how much flexibility instructors reasonably need to give online students, and this is a complicated question—often prompted by instructors who are doing their best to navigate difficult situations with students who need a lot of support and have their own high workloads. One suggestion that we give is for instructors to avoid the impulse to find a solution themselves and to ask the student to draft a plan for how they might catch up. Putting the onus back on the student actually gives them more agency over their situation. Sometimes students realize in the process of putting together a plan that it is not feasible to catch up within that term and that they need to withdraw or take an incomplete. In other cases, students will present a reasonable plan (or one that can become reasonable with a bit of instructor feedback). They may be more likely to stick to it because it is their plan and accounts for their circumstances. This kind of approach demonstrates the same kind of flexibility that we are advocating for generally, one that demonstrates an open mind and a willingness to work with students on creative solutions to support their success. It also validates that online students deserve agency in their educational journey to make choices that will work for them.

During-the-Term Strategies

The following suggestions for what to do during the term are centered in the notion that we want to communicate trust and support to students and that their instructors notice their presence and—when it happens—their absence.

Demonstrate Care for Students as Individual Human Beings

Adult students are often balancing work, school, family, and other personal commitments but have a unique drive to advance their education—after all, taking on all of this at once is admirable. While many online students have developed the knowledge and skills to manage their time, establish their own goals, and ask for help when they need it, not all students have the resilience to succeed academically when they experience mental or emotional stress. Some students may be willing to share the challenges and difficulties that they are experiencing with their instructors, while in other cases, students may worry about disclosing what could be perceived to be weaknesses when they ask for help (Spindell Bassett 2021). But there are many ways in which instructors can help students who are experiencing challenges in their life to thrive and develop resilience. Caring about students and showing them empathy, for example, can lead students to be more successful (Meyers et al. 2019).

OSU Ecampus students often praise instructional instructors who see them as human beings rather than as just another student (or a student identification number). The person-centered model in psychology, drawing from the work of Carl Rogers, provides a helpful framework for considering how students could be approached in a truly humanized way when they encounter difficulties inside or outside of the classroom that have bearing on their progress in the course. Johnson (2021) points out that the primary question in a student-centered model of education is “Do you understand?” whereas the primary question in a person-centered model is “Who are you?” (37). Seeing the student as more than just their quantified learning and understanding can open up additional ways to connect with your students on a level that adult students will particularly appreciate because of the complexities that they are managing in their lives. For example, a person-centered approach to online teaching might prompt you to:

- Destigmatize students’ vulnerability and mistakes and how you talk to students about the process of learning.

- Be a listening ear about anything they bring to you. You do not need to have all of the answers or solutions and can refer students to specialized help or resources.

- Lean into students’ individual academic and professional interests rather than only the content that the course is conveying.

Person-centered approaches can be particularly helpful when a student is facing major challenges inside or outside of school. In that situation, guide their focus so that they are working on only what is most important in the course. For some of our students, just passing a course (particularly challenging general education or prerequisite courses) is enough, whereas their instructors might hope for all students to aim for high grades. Listen for what the student’s aspirations are for the course, and help them work toward those goals rather than your own goals for them. Additionally, most instructors want to share their love for their discipline with their students, and that can result in extra, optional resources and activities included in an online course that may not clearly be marked “optional.” When needed, help the student find the shortest meaningful path to meeting the course learning outcomes; that is yet another way to understand that you appreciate the challenges they are facing and want to enable their success.

Boundaries are important when working with all students, including online students. There is a risk of establishing relationships that are too personal (Chory and Offstein 2017), but keep in mind that the online education environment is, by default, very impersonal. You may want to consider how to offset that impersonable default by communicating more or differently with your online students to bridge the digital gap. An easy, low-risk example is being less formal in your written communication with students than you would be verbally with your in-person students, which can make the online learning environment feel more humanized even as you set and maintain boundaries.

Connect Students to Resources

As we have discussed in previous chapters, your syllabus is a great place to begin creating a welcoming climate, and in that document, you can highlight how you can help students with more than just content. Your institution may have a boilerplate student success statement or links to resources that you must use, but you can also add language encouraging students to reach out to you if they need help navigating the academic and nonacademic resource network at the institution.

True distance students—those who do not live near your institution’s campus—may not be able to travel to campus and may not be aware of institutional resources available to them. Students who are taking classes part time and at a distance are even more likely to be disconnected from the campus and unaware of resources, including resources that they may be paying for as part of their student fees. Instructors play a critical role in helping these students to make connections. To help raise awareness about the resources available to online students, you might consider adding a page about or linking to information about student services. Many course syllabi are so lengthy due to required language that resources can get lost there, so adding a brief reminder through an announcement and/or a link somewhere more prominently in the course can be helpful.

Additionally, knowing the particular challenges that adult learners face, it is a good idea to familiarize yourself with institutional resources that are available to online students in the following areas.

- Mental health: You may hear concerning information from a student or suspect that a crisis is imminent, and it is a good idea to have a plan for how to connect that student to available resources. Each state has different laws governing how and if mental health counseling resources can be deployed across state lines, which has an obvious impact for working with geographically dispersed students. Generally speaking, you can also gently ask the student to follow up with you later that day or the next day to help them stay accountable to their next steps for connecting to support services and also to demonstrate that you care about their well-being.

- Financial concerns: Adult students tend to have competing financial pressures, and just one unexpected bill can derail their plans for the term. Some OSU Ecampus students have reported making difficult choices between purchasing the required textbook or purchasing food. Online students are also dependent on their personal phones, computers, and Internet connections in order to participate in classes, so a laptop that suddenly stops working is suddenly a major problem if they cannot easily and quickly secure a replacement. Know where to send students if financial issues are interfering with their success in your course. OSU Ecampus offers a financial hardship grant for undergraduate online students, as one example of the support you might be looking to identify (or advocate for) at your own institution.

- Additional academic support: Your online students may reach out to you with more generalized concerns about stress and anxiety related to school, time management skills, the need for someone to help them stay accountable, and more. Find out if and how your institution supports online students in these areas. OSU Ecampus offers success coaching for online students, for example.

You do not have to be an expert on student resources to be able to help; your institution’s student life office or your department’s academic advisors can often identify the most relevant resources for you to share with the student, rather than immediately passing them along to yet another strange office or staff member on campus to whom they have to explain their situation. Even if the student ultimately does need to work with another office or individual, you can provide a “warm handoff.” Students (especially low-income, first-generation students) may be more apt to utilize resources that their instructor recommends (Spindell Bassett 2021).

Communicate Support and Encouragement to Nonresponsive and Struggling Students

Connecting individually with students who demonstrate concerning behaviors in an online class—including disengagement and low performance—is a good first and early strategy to support students who may need it most. The effectiveness of “nudging” students, or trying to affect behavioral change with an encouraging message, is contested in studies that have focused on prompting students to complete routine tasks like registering for classes. There is some evidence, however, that an instructor reaching out to offer support and encouragement is effective in the context of a course (Berrett 2018; Supiano 2018).

Ideally, your course will have low-stakes or formative activities and assignments within the first few weeks of the term, which will give you insight into each student’s progress in the course. Consider checking in with students based on the following behaviors:

- No participation in the course by the second week of the term

- Regular participation in the course followed by sudden nonparticipation

- Less-than-passing score on the first major assignment (e.g., exam or paper)

- Less-than-passing score in the course at the term midpoint

Your institution’s LMS may have features that help you send these messages efficiently. In Canvas, for example, the gradebook includes a “message students who . . .” feature that allows instructors to selectively message students based on particular criteria, such as not submitting work or scoring below an instructor-identified threshold. In this scenario, any student who meets the criteria will receive an individual copy of the instructor’s message. In Canvas’ New Analytics, instructors can send similar kinds of messages but using criteria from the whole course rather than one individual assignment, such as students who have a current course grade below an instructor-identified percentage.

The key is to craft a warm, helpful, and encouraging message that identifies resources and possible next steps; avoid language that can be perceived as judgmental about where a student’s progress currently stands. Also, take into account the functionality of any messaging feature that you are using: Canvas, for example, currently does not automatically include the student’s name in the message, and so a generic opening has to be used. Included below are two examples of messages that model effective outreach during the term.

TO: Students who scored less than 70% on the course midterm

SUBJECT: Checking in about ABC 350 midterm score

Good afternoon,

I’m writing to you to check in about your ABC 350 midterm score, which was below the passing range. I want you to know that this was a very challenging exam and that there is still a lot of time and opportunity to raise your grade. More importantly, please be assured that I am here to help and that I want to ensure you understand the exam material so that you can effectively build on it in the coming weeks.

I am holding a special post-midterm exam review session this Friday from 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. (PT). This will be a time to go over remaining questions related to the exam. If you are unable to attend live, that is just fine—you can submit questions to the anonymous weekly question box, and I will answer them and post the recording. You are also welcome to attend the scheduled TA office hours this week or schedule an appointment with a TA.

Your success is really important to me. Please let me know how I can help!

TO: Students who have less than a 70% at term midpoint

SUBJECT: Checking in about CDE 100 grade

Good afternoon,

I’m writing to you to check in about your CDE 100 grade, which is currently below passing as we approach the midpoint of the term. This is a challenging course, but there is certainly still time and opportunity to raise your grade, and I am here to help you succeed in the second half of the term.

However, I also recognize that circumstances can arise that make it challenging to finish a course, and [institution name] has a withdrawal process available if you believe that may be the right choice for you. I encourage you to consult with your academic advisor first to make sure you make an informed decision.

I have office hours this Wednesday from 5:00 to 6:00 p.m. (PT), or I would be happy to make an appointment at a mutually agreeable time if you would like to discuss your progress in the course and how we can work together toward your success.

These forms of outreach may sometimes, but not always, have effective results in reengaging students or connecting them to resources that will help them pass the course. Remember that you can gently offer resources about university processes like withdrawal (or late withdrawal by petition) as needed, too. If the student reads your message, they hopefully will appreciate that you have noticed their absence or the challenges that they are facing in the course, which can help them feel seen even in the midst of difficult times.

Offer Helpful, Actionable, and Timely Feedback

When we talk about equity and inclusivity in any course, assignment feedback is a key area of teaching practice to reconsider. Feedback from an instructor can encourage or dissuade a student from continuing on in the course and in their education, can support a growth mindset or reinforce harmful and inaccurate stereotypes, and can help a student make strides in developing additional academic strengths or stall their progress. In an online course, feedback is particularly important because it is one of the regular communications you will establish individually with that student, and regular feedback can help online students avoid feeling isolated and alone in their learning (Martin et al. 2020). Importantly, the feedback must also be timely so that the student receives it and has time to absorb and apply it before additional coursework is due.

Helpful, actionable feedback tends to look similar between online courses and courses in other modalities. If you are new to teaching online, an excellent introduction to grading best practices (across modalities), and particularly the importance of rubrics and good rubric development, is Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment in College, by Walvoord and Anderson (2010). Instructor feedback plays a special role in online education where students need to engage more self-regulation skills in order to succeed, however, particularly as students are developing the ability to evaluate their own work (Artino 2008; Tsai 2009; Sharp and Sharp 2016; Wandler and Imbriale 2017). In particular, Jantz (2010) notes that feedback on process rather than a student’s intelligence or innate ability can help to build self-regulation and self-efficacy skills:

Process feedback promotes the importance of how students work. It emphasizes the ideas, strategies, choices, development, and execution that students used to create their work. Process feedback also highlights methods students can use to repeat success and overcome challenge[s]. This approach presents feedback as part of an ongoing interchange rather than as an evaluation. As a result, it helps students to value learning, to enjoy effort and challenge, and to thrive in the face of difficulty. (855)

This kind of feedback is most useful in the context of formative and strengths-based assessments, thereby helping students to chart progress on their path to meeting course learning outcomes.

So much about good online teaching practice comes from deeply understanding not just your course content but also the way that a course scaffolds learning across the term. For example, do you know how activities, assignments, and assessments are related to module-level learning outcomes (if included) and course-level learning outcomes? Most universities use a curricular approval process to inform the course’s scope and content, so you may need to consult any approved outcomes for your course. If you have a sense of how each part of your course works together to support students in meeting outcomes, then you will have a better idea of how to give directed, specific, and helpful feedback to students during the term. You will also need to have a good understanding of the pace of the course and how activities are interconnected to see how quickly you will need to return grades and feedback.

One helpful way to identify what kind of feedback students need is to distinguish between diagnostic, formative, and summative assessment. Diagnostic assessment is used at the beginning of a course to understand what skills, expertise, and experience students are bringing into the course, which might be helpful to implement as a way to understand how you can meet your students where they are. Then, formative assessment happens during the course (or within major units), and summative assessment happens at the end of the course (or at the end of major units). Most important for our purposes here is to focus on formative assessment, which is usually the key time and opportunity for instructors to provide the kind of commentary that helps students to engage and make progress on meeting learning outcomes as the term proceeds.

As its name suggests, formative assessment emphasizes the formation of the student’s knowledge and skills, so feedback is necessary to help the student to accurately identify strengths and weaknesses, and also to determine practical next steps for improvement. Bain (2004) posits formative assessment as philosophically different from summative assessment, identifying formative approaches as “assessment to help students learn, not just to rate and rank their efforts” (151). To that end, formative assessments usually require some sort of written feedback to each student, and the comment(s) should be balanced in their articulation of what students are doing well and where and how they can improve. Simply telling a student that they need to work on APA citation style, for example, is different from foregrounding feedback with that note and then providing an example of where a source introduction could have been clearer and a citation needed to be structured differently. Strong formative feedback takes time and careful thought to develop because it is specific and actionable. For efficiency, your institution may allow you to curate prewritten text that addresses the most common kinds of feedback your students receive, and to use that text as you develop feedback for individual students. Feedback should always be accurate and personal, though, addressing the student by name and identifying at least one feature that is specific to their work as part of the feedback.

In constructing formative feedback, bear in mind that your students may be vulnerable to “stereotype threat.” Assumptions that genetics, gender, or cultural differences can predict whether a student will or will not succeed academically are still prominent even though research has proven these assumptions to be false. Yet if negative group stereotypes are called up for students, such as within a high-stakes testing environment or in a challenging major or course, their performance may not be as strong, and this phenomenon is what psychologists have termed “stereotype threat.” You can help students avoid the negative effects of stereotype threat in the following ways.

- Ensure that voices and pictures of experts from different backgrounds are represented in your course (e.g., they are not all white male figures). This approach sets the stage for diverse students seeing themselves as capable of participating in and succeeding in the field of study.

- Avoid quick judgments about any student’s potential that might inadvertently influence how you interact with them. A study with science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) faculty concluded that “faculty mindset beliefs predicted student achievement and motivation above and beyond any other faculty characteristic” (Canning et al. 2019).

- Emphasize a growth mindset with students, particularly as you provide formative feedback. Research on neuroscience and learning has shown that intelligence is not fixed; rather, “fluid intelligence” includes aspects of intelligence that can be improved with training: working memory, attention, reasoning, problem-solving, and so on (Tokuhama-Espinosa 2018, 22). Yet this myth of fixed intelligence still persists among both students and instructors. When you provide well-earned praise, be sure to attribute the student’s successes to the student’s effort, not to their intelligence or predisposition for doing something well. When you provide a constructive critique, help the student see that there are more opportunities to learn and that the challenge is not insurmountable (especially with your help!).

The importance of how you frame feedback to online students simply cannot be overemphasized. In a qualitative study about the most important skills for successful teaching online, long-term instructors emphasized the importance of communication and particularly of tone (Dello Stritto and Aguiar 2024). Students may not be able to decipher humor and sarcasm in writing, so use those approaches with extreme caution. As you reflect on your feedback tone, you might ask yourself: What possible ways could a well-meaning (but possibly self-doubting) online student misread what I am trying to tell them?

In the following interactive examples, you will see a brief sample of instructor feedback. Consider if the feedback could be improved before turning the card to see some considerations for revision.

Finally, consider the important impact of timely feedback on student learning in your course. Many online courses organize learning content and activities into weekly or biweekly modules or units, and there may be some regularity or pattern to the types of work assigned; this structure informs just how quickly feedback needs to be returned. Take discussion activities in an internship course, for example. Perhaps they are used every week as an application activity, asking students to apply new knowledge that they have gained to their internship site. Ideally, students need feedback fairly quickly, especially after the first few application activities to help them get a sense of whether they are on the right track; in this case, the instructor might aim to return feedback in five days so that students have two days to review feedback before the next post is due. Grant Wiggins (2012) also makes a key clarification that is especially important for online instructors who have a high workload: “I don’t want my teacher or the audience barking out feedback as I perform. That’s why it is more precise to say that good feedback is ‘timely’ rather than ‘immediate’” (14).

Timely feedback offers student learning benefits in any modality (Ambrose 2010; Walvoord and Anderson 2010; Wiggins 2012). But it has been identified as one of the most helpful facilitation strategies for enhancing online student engagement and learning based on both student (Martin et al. 2018) and instructor perceptions (Martin et al. 2020).

Reflection and Action

In this chapter, we have covered many concrete, actionable online teaching strategies that can be used to support adult online students. If you are currently teaching an online course, consider implementing one or more of the suggested action items below this term; others may take more time and may be more appropriate to implement in a future course offering. Then, we invite you to continue on to chapter 5, where we discuss specific strategies to facilitate inclusive discussions in online classrooms.

You Might Be Ready to . . .

- Adjust an upcoming assignment or assessment to be more transparent.

- Monitor your students’ progress this term and engage in proactive outreach.

- Identify where additional resources or refresher materials may be helpful, and share them with students.

- Connect students to resources that may be appropriate to the course and time in the term.

- Practice giving more helpful, actionable feedback, including growth mindset strategies.

Questions for Further Consideration

- What do you wish you knew about your students? Is there a way you can find out, particularly through implementing a beginning-of-term survey? What would you do with that information?

- Which of the practices discussed in this chapter may have the most impact on your students? How do you know? How would you informally track or assess changes that you make to your teaching?

- Feedback is an incredibly important teaching task, but it takes a lot of time to do well. Where in your online course(s) is feedback most critical? How do you (or might you) balance being effective, inclusive, and efficient in your feedback?

References

Ambrose, Susan A. 2010. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Artino, Anthony R. Jr. 2008. “Promoting Academic Motivation and Self-Regulation: Practical Guidelines for Online Instructors.” TechTrends 52 (3): 37-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-008-0153-x.

Artze-Vega, Isis, Flower Darby, Bryan Dewsbury, and Mays Imad. 2023. The Norton Guide to Equity-Minded Teaching. W.W. Norton.

Bain, Ken. 2004. What the Best College Teachers Do. Harvard University Press.

Berrett, Dan. 2018. “How One Email from You Could Help Students Succeed.” Chronicle of Higher Education, August 9, 2018. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2018-08-09.

Canning, Elizabeth A., Katherine Muenks, Dorainne J. Green, and Mary C. Murphy. 2019. “STEM Faculty Who Believe Ability Is Fixed Have Larger Racial Achievement Gaps and Inspire Less Student Motivation in Their Classes.” Science Advances 5 (2): 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4734.

Chory, Rebecca M., and Evan H. Offstein. 2017. “Your Professor Will Know You as a Person: Evaluating and Rethinking the Relational Boundaries with Students.” Journal of Management Education 41 (1): 9-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916647986.

Dello Stritto, Mary Ellen, and Naomi R. Aguiar. 2024. “Skills Needed for Success in Online Teaching: A Qualitative Study of Experienced Instructors.” Online Learning Journal 28 (3): 585-607. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v28i3.3518.

Denial, Catherine J. 2024. A Pedagogy of Kindness. University of Oklahoma Press.

Fetzner, Marie. 2013. “What Do Unsuccessful Online Students Want Us to Know?” Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 17 (1): 13-27. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v17i1.319.

Gordon, Jessica. 2017. “Creating Social Cues through Self-Disclosures, Stories, and Paralanguage: The Importance of Modeling High Social Presence Behaviors in Online Courses.” In Social Presence in Online Learning: Multiple Perspectives on Practice and Research, edited by Aimee L. Whiteside, Amy Garrett Dikkers, and Karen Swan. Stylus.

Henning, Marcus A., and Emmanuel Manalo. 2014. “Motivation to Learn.” In Student Motivation and Quality of Life in Higher Education, edited by Marcus Henning, Christian Krägeloh, and Glenis Wong-Toi, 17-27. Routledge.

Hokanson, Brad, Gregory Clinton, and Karen Kaminski. 2017. Educational Technology and Narrative: Story and Instructional Design. Springer.

Howard, Tiffany O., Mary-Ann Winkelmes, and Marya Shegog. 2020. “Transparency Teaching in the Virtual Classroom: Assessing the Opportunities and Challenges of Integrating Transparency Teaching Methods with Online Learning.” Journal of Political Science Education 16 (2): 198-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2018.1550420.

Jantz, Carrie. 2010. “Self Regulation and Online Developmental Student Success.” Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 6 (4): 852-57.

Johnson, Anna M. 2021. “Person-Centered Pedagogy in an Asynchronous Online Environment: Elements of a Person-Centered Instructor.” Journal of Instructional Research 10: 36-46. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1314153.pdf.

Kember, David. 2016. Understanding the Nature of Motivation and Motivating Students through Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. 1st ed. Springer Singapore.

Knight, Amy. 2022. “4 Ways to Design a Course That Supports Neurodivergent Students. Focus on Highlighting their Strengths.” Harvard Business Publishing Education, August 21, 2022. https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/4-ways-to-design-a-course-that-supports-neurodivergent-students.

Martin, Florence, Chuang Wang, and Ayesha Sadaf. 2018. “Student Perception of Helpfulness of Facilitation Strategies That Enhance Instructor Presence, Connectedness, Engagement and Learning in Online Courses.” The Internet and Higher Education 37: 52-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2018.01.003.

Martin, Florence, Chuang Wang, and Ayesha Sadaf. 2020. “Facilitation Matters: Instructor Perception of Helpfulness of Facilitation Strategies in Online Courses.” Online Learning 24 (1): 28-49. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i1.1980.

Merriam, Sharan B., and Laura L. Bierema. 2013. Adult Learning: Linking Theory and Practice. Jossey-Bass.

Messineo, Melinda. 2018. “The Science of Learning in a Social Science Context.” In Learning from Each Other: Refining the Practice of Teaching in Higher Education, edited by Michele Lee Kozimor-King, and Jeffrey Chin. University of California Press.

Meyers, Sal, Katherine Rowell, Mary Wells, and Brian C. Smith. 2019. “Teacher Empathy: A Model of Empathy for Teaching for Student Success.” College Teaching 67 (3): 160–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2019.1579699.

Miller, Melissa Lynn. 2021. Mind, Motivation, and Meaningful Learning: Strategies for Teaching Adult Learners. Association of College and Research Libraries.

Pacansky-Brock, Michelle. 2024. “Getting to Know You Survey.” Accessed January 22, 2024. https://brocansky.com/humanizing/student-info.

Pritts, Nathan. 2020. “Using Announcements to Give Narrative Shape to Your Online Course.” Faculty Focus, June 1, 2020. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/online-course-design-and-preparation/using-announcements-to-give-narrative-shape-to-your-online-course/.

Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric. 7th ed. 2023. Quality Matters. https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf.

Rider, Jennifer. 2019. “E-Relationships: Using Computer-Mediated Discourse Analysis to Build Ethics of Care in Digital Spaces.” In Care and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy in Online Spaces, edited by Lydia Kyei-Blankson, Joseph Blankson, and Esther Ntuli, 192-212. IGI Global.

Rognlie, Dana L., Kathryn E. Frazier, and Elizabeth A. Siler. 2025. “What Does It Mean to ‘Humanize’ Online Teaching?” In Feminist Pedagogy for Online Teaching, edited by Jacquelyne Thoni Howard, Enilda Romero-Hall, Clare Daniel, Niya Bond, and Liv Newman. Athabasca University Press.

Sharp, Laurie A., and Jason H. Sharp. 2016. “Enhancing Student Success in Online Learning Experiences through the Use of Self-Regulation Strategies.” Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 27 (2): 57-75.

Shea, Peter. 2024. “Teaching Presence as a Guide for Productive Discussion Design in Online and Blended Learning.” In The Design of Digital Learning Environments: Online and Blended Applications of the Community of Inquiry, edited by Martha Clevenland-Innes, Stefan Stenborn, and D. Randy Garrison, 68-83. Routledge.

Sogunro, Olusegun. 2015. “Motivating Factors for Adult Learners in Higher Education.” International Journal of Higher Education 4 (1): 22-37. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v4n1p22.

Spindell Bassett, Becca. 2021. “Big Enough to Bother Them? When Low-Income, First-Generation Students Seek Help from Support Programs.” Journal of College Student Development 62 (1): 19-36. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2021.0002.

Supiano, Beckie. 2018. “Insights from Other Instructors.” Chronicle of Higher Education, September 14, 2018. https://www.chronicle.com/article/insights-from-other-instructors.

TILT Higher Ed. 2024. “TILT Higher Ed Examples and Resources.” Accessed November 27, 2024. https://www.tilthighered.com/resources.

Tokuhama-Espinosa, Tracy. 2018. Neuromyths: Debunking False Ideas about the Brain. W. W. Norton.

Tsai, Meng-Jung. 2009. “The Model of Strategic e-Learning: Understanding and Evaluating Student e-Learning from Metacognitive Perspectives.” Journal of Educational Technology and Society 12 (1): 34-38.

Waghid, Yusef. 2019. Towards a Philosophy of Caring in Higher Education: Pedagogy and Nuances of Care. Palgrave Macmillan.

Walvoord, Barbara E. Fassler, and Virginia Johnson Anderson. 2010. Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wandler, Jacob, and William John Imbriale. 2017. “Promoting College Student Self-Regulation in Online Learning Environments.” Online Learning 21 (2). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i2.881.

Wiggins, Grant. 2012. “7 Keys to Effective Feedback.” Educational Leadership 70 (1): 10-16.

Winkelmes, Mary-Ann, David E. Copeland, Ed Jorgensen, Alison Sloat, Anna Smedley, Peter Pizor, Katharine Johnson, and Sharon Jalene. 2015. “Benefits (Some Unexpected) of Transparently Designed Assignments.” National Teaching and Learning Forum 24 (4): 4-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ntlf.30029.

Winkelmes, Mary-Ann, Matthew Bernacki, Jeffrey Butler, Michelle Zochowski, Jennifer Golanicks, and Kathryn Harris Weavil. 2016. “A Teaching Intervention That Increases Underserved College Students’ Success.” Peer Review: Emerging Trends and Key Debates in Undergraduate Education 18 (1-2): 31-36.

Wlodkowski, Raymond J. 1999. Enhancing Adult Motivation to Learn: A Comprehensive Guide for Teaching All Adults. Rev. ed. Jossey-Bass.

Wood, J. Luke, Frank Harris III, and Khalid White. 2015. Teaching Men of Color in the Community College: A Guidebook. Montezuma Publishing.

- See the Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric, 7th ed. (Quality Matters, 2023), Specific Review Standard 1.9. ↵