7 Guiding Instructional Faculty along Their Inclusive Teaching Journey

Introduction

This chapter discusses key lessons learned from developing and implementing the Inclusive Teaching Online (ITO) workshop at Oregon State University Ecampus. The ITO workshop has been as much of a journey for those of us involved in creating it, facilitating it, pursuing research about faculty development in it, presenting about it, and writing this book about its practices and strategies as it has been for the instructors who have participated in the workshop. In this chapter, we provide an overview of the process of creating the workshop, launching and facilitating it, revising it, and the research project associated with it. Specifically, we present selected key results of the research project that aimed to answer questions about how to provide effective professional development to instructional faculty on these topics, and what inclusive practices instructors have implemented and found to be most effective in their online courses. Finally, we share our own observations about working with instructors as they advance their understanding of how to apply tenets of inclusive excellence in their online courses. Readers who are instructors may find particular interest in hearing from our workshop participants about what inclusive teaching practices they have applied and how those practices are working. This chapter will also be of interest to faculty developers and instructional designers who may offer professional development opportunities to instructional faculty, assist them through consultation or observation, or otherwise support instructors on continuous teaching improvement.

Establishing Partners and Collaborators

Key to the successful launch of the ITO workshop was early and ongoing collaboration with campus partners. Many colleagues across campus were training and supporting instructors in improving their teaching, but often with a different goal or approach than we were taking. Yet drawing on the work of other expert colleagues, having a strong awareness of other opportunities that instructors may have previously engaged in, and determining where our workshop could begin and what we needed to cover that was not being addressed elsewhere, ITO became a unique professional development resource for our instructional faculty.

Our primary collaborators on content and content review included Jane Waite, the director of the Social Justice Education Initiative at OSU, and Jeff Kenney, the director of institutional education in diversity, equity, and inclusion in our Office of Institutional Diversity. Many other colleagues participated along the way, too, especially colleagues in student affairs and student services who know deeply the needs of our diverse student body.

Identifying Gaps in Faculty Development for Inclusive Teaching

Looking ahead to the research that we wanted to pursue alongside the workshop, we sought a benchmark for how instructors perceived their ability to model inclusive excellence in their online courses before we launched ITO. We began with an initial survey to all Ecampus instructors in December 2019, which helped us to understand how much value instructors placed on various inclusive teaching approaches and how much confidence they had in employing those approaches. All “current” Ecampus instructors (defined as teaching a fully online section of a course in the current term or within the past two years) as of the fall quarter 2019 were invited to participate in this short, anonymous survey. Survey results provided valuable insights about instructors’ perceptions of their strengths related to online teaching and potential gaps where we could offer professional development.

We received 110 valid responses to this survey, or 19% of our instructional faculty teaching online in that quarter. We received responses from every college that had courses or programs online in 2019, though the proportion of responses by college did not reflect the proportion of all online instructors by college.

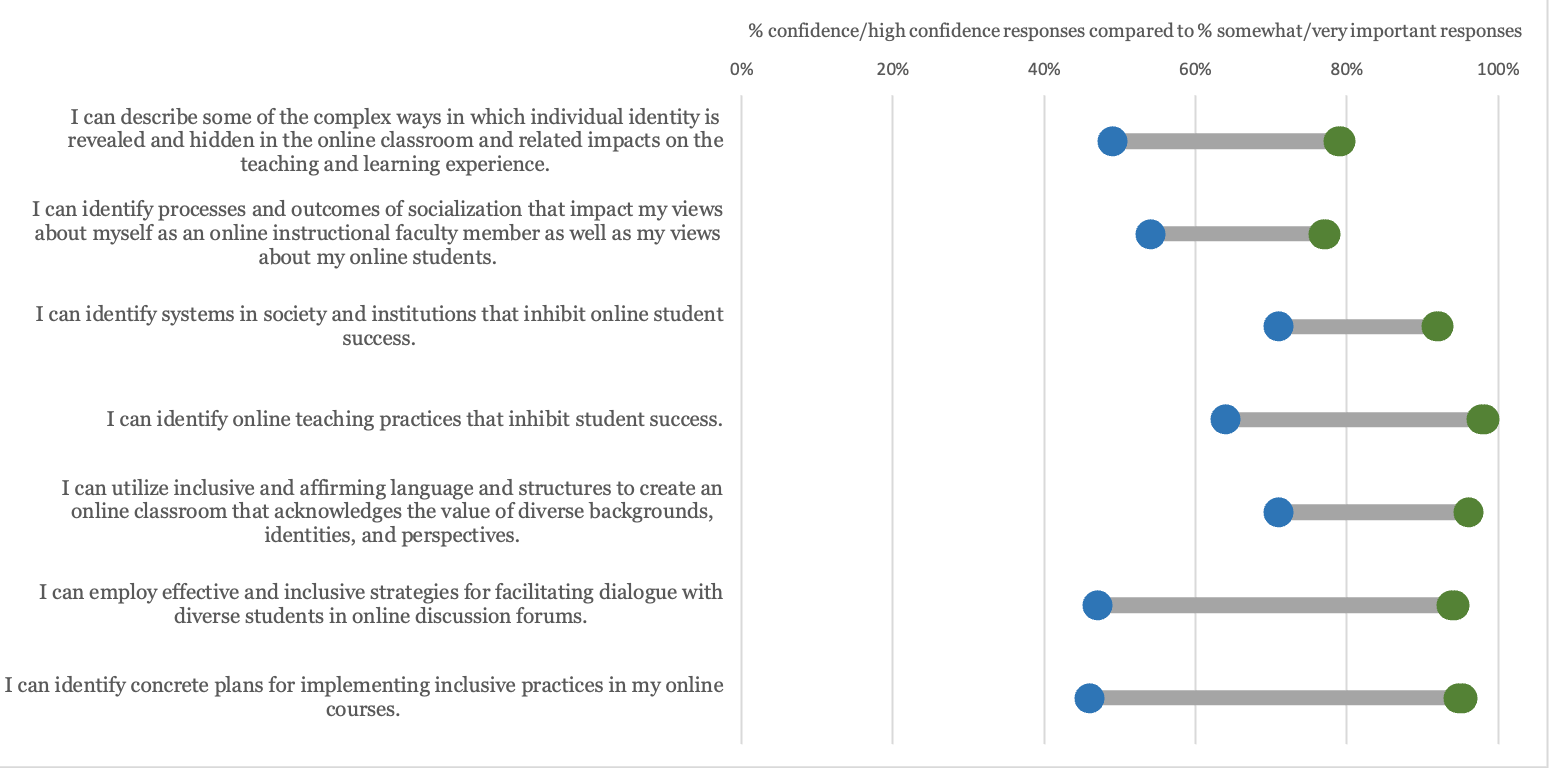

One of our areas of inquiry with this survey was to identify professional development gaps by comparing instructors’ self-identified confidence in certain areas of inclusive online teaching against the relative importance that they personally place on those skills. Figure 7.1 illustrates the percentage of respondents who indicated that they have “confidence” or “high confidence” in each area, compared to the percentage of respondents who indicated that each area is “somewhat important” or “very important.” The result illustrates potential professional development gaps, revealing where instructors believe a skill is important but are not confident in their abilities.

As shown in figure 7.1, the larger gaps related to dialogue facilitation in online courses and identifying concrete plans for implementing inclusive teaching practices, which reaffirmed that a workshop would be a useful support for instructors if it introduced practical ideas and strategies. The results suggested to us that the workshop should also provide a collegial, judgment-free place for instructors to explore, try out, and talk about what they might do—and that we should lean into those areas because other professional development offerings did not cover them.

In this survey, respondents also identified internal (to OSU) and external professional development opportunities that had allowed them to explore social justice themes in education, implicit and explicit bias in social processes and institutions, and using affirmative language with students, for example. Gaps related to those items were smaller, so we focused less on these than other areas where we could expand professional development topics offered at OSU.

Building, Launching, and Revising the ITO Workshop

We began to build out pieces of the workshop in collaboration with colleagues on our campus who are deeply knowledgeable about scholarship related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and who are equally passionate about helping instructors to build inclusive classrooms. We were fortunate to partner with collaborators from across campus who were instrumental in helping us to identify and adapt frameworks for synchronous and in-person teaching that had not yet been translated to online teaching and learning contexts.

As we were designing the workshop, we carefully considered our audience and needs based both on what we learned from the initial instructor survey and the faculty culture at OSU. The primary audience for the workshop has always been online instructors, whether or not they designed the courses that they teach. In fact, similar to our approach in this text, we lean most heavily into facilitation-related choices that instructors and faculty of all ranks usually have the power to make during the workshop, knowing that many online instructors do not have the power to change the designs of their courses in small or large ways. We have had graduate teaching assistants, full-time instructors, part-time instructors, and tenure-track faculty complete the workshop because we have focused on the common denominator in all of their teaching responsibilities: how they interact with students. We were not able to provide financial compensation for workshop participation or completion, so we aimed to keep the time commitment per week reasonable, knowing that our instructors are busy.

We made an important choice early on to add a “soft prerequisite” to our workshop: we asked that instructors engage with the first level of the Social Justice Education Initiative (SJEI) workshops before taking ITO. We called SJEI a “soft prerequisite” because we did not enforce it, but that approach allowed us to proceed with some certainty that many or most of our participants would come into our workshop with a baseline knowledge of inclusion-related terminology and frameworks. This baseline knowledge allowed us to start immediately with some deep, reflective questions, asking instructors to fairly quickly begin to apply ideas within the workshop.

The ITO workshop was initially set up as a four-week workshop, run asynchronously through Canvas, our learning management system. We enroll instructors in the workshop as students. The student role is intentional: instructors often notice and comment along the way about how much empathy they gain for online students—when they get confused, when they suddenly realize that they missed a deadline, and when they need to ask for extensions—since they themselves are experiencing what it is like to be an online student through a multi-week workshop. We also aim to model best practices in online facilitation to and with instructors, and they get to experience an online “course” as if they were a student. As a few specific examples of this modeling, we:

- Use an inclusion statement in our workshop syllabus and reference that statement as we talk about our own approaches, how we communicate them up front, and then implement them. That statement goes beyond just being placed in the syllabus; it is made concrete throughout the workshop.

- Post meaningful weekly announcements that recap the previous week’s lessons and connect ideas that have come up for the group to upcoming topics and activities. We also highlight specific ideas that have shown an interesting approach or that have been innovative in some way.

- Articulate all assignment prompts in the Transparent Assignment Design (TAD) framework and provide detailed rubrics.

- Provide personalized and actionable feedback to participants on each of their activities, within a few days of their submission.

- Actively facilitate discussions, chiming in and adding follow-up questions to help instructors step out of their comfort zones or consider another perspective.

- Engage in proactive outreach with participants who are falling behind and talk about ways to move forward.

- Adjust due dates and timelines as needed to support busy instructor participants or address personal matters that impact their participation in the workshop.

In 2023, we extended the workshop structure to seven weeks in response to the primary constructive feedback from past participants that the workshop length was too short. Participants indicated that there was not enough time to process and reflect on ideas before moving along to the next topic or activity, and we had observed that instructors were experiencing some difficulties in keeping to the pace of the four-week structure. Figure 7.2 compares the two workshop timelines, including how we restructured content in the longer version.

Four-week Module 2 (Barriers to Student Success in the Online Classroom and Inclusive Responses) aligns with Seven-week Modules 3 (Reducing Barriers in the Online Classroom) and the start of Module 4 (Supporting Online Students through Transparency, Outreach, and Feedback).

Four-week Module 3 (Putting Inclusivity into Practice Online, Part I) aligns with the remainder of Seven-week Module 4 (Supporting Online Students through Transparency, Outreach, and Feedback), Module 5 (Facilitating Online Discussions Effectively and Inclusively, Part I), and the start of Module 6 (Facilitating Online Discussions Effectively and Inclusively, Part II).

Four-week Module 4 (Putting Inclusivity into Practice Online, Part II) aligns with the remainder of Seven-week Module 6 (Facilitating Online Discussions Effectively and Inclusively, Part II) and Module 7 (Vision and Action Plans).

When we moved to the seven-week format, we revised some activities to make them more action oriented. We encourage instructors who are teaching an online course during the term in which they take the workshop to try out one of the approaches and strategies presented in their course that week and then report back on how it is working as their discussion activity for the workshop. For example, rather than talk generally about effective and inclusive discussion board facilitation strategies, we ask participants to try out a new “facilitation role” in their course’s current online discussion and share how it went as part of their discussion with colleagues. There is always an alternative prompt for instructors who are not teaching online in the term in which they take ITO.

Otherwise, the content of the workshops has remained mostly the same, with learning materials, activities, and deliverables simply becoming more dispersed across time in the seven-week version of the workshop. Keeping continuity in our primary materials and activities has allowed us to continue to compare results across our research study, even after we lengthened the workshop timeline.

Key Insights from Researching Online Faculty Development in Inclusive Teaching

Since our first offering in winter quarter 2020, we have led six cohorts through the ITO workshop. Instructor registrants are invited to participate in our research study at the beginning of the workshop, but they can also participate fully in the workshop without taking part in the study.

We have four main assessment points used in data collection and comparison, each of which will be discussed below:

- A pre-workshop survey, where we collect baseline data about incoming participants’ level of confidence in key skills related to inclusive online teaching.

- A final vision and action plan, where participants identify what has been most useful in the workshop and what they plan to implement.

- A post-workshop survey, where we collect follow-up data on participants’ level of confidence in key skills related to inclusive online teaching.

- A “two terms later” survey, where we invite participants to reflect on the workshop strategies they have implemented and have found most impactful.

Assessing Transformation through Pre- and Post-Workshop Survey Results

In pre- and post-workshop surveys, we ask participants to self-identify their levels of confidence with the same seven skill areas related to inclusive online teaching that we surveyed earlier with all online instructors in 2019. Table 7.1 compares the resulting data across all instructors who participated in the research study and completed all workshop activities (n = 78).[1] The survey provided a Likert scale of 1-5, with 1 indicating “very low confidence” and 5 indicating “very high confidence.”

| Skill Area | Average Pre-Survey | Average Post-Survey | Average Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| I can describe some of the complex ways in which individual identity is revealed and hidden in the online classroom and related impacts on the teaching and learning experience. | 2.90 | 3.56 | +0.66 |

| I can identify processes and outcomes of socialization that impact my views about myself as an online instructional faculty member as well as my views about my online students. | 3.46 | 3.55 | +0.09 |

| I can identify systems in society and institutions that inhibit online student success. | 3.52 | 3.36 | -0.15 |

| I can identify online teaching practices that inhibit student success. | 2.96 | 4.18 | +1.22 |

| I can utilize inclusive and affirming language and structures to create an online classroom that acknowledges the value of diverse backgrounds, identities, and perspectives. | 3.90 | 4.50 | +0.60 |

| I can employ effective and inclusive strategies for facilitating dialogue with diverse students in online discussion forums. | 3.83 | 4.26 | +0.42 |

| I can identify concrete plans for implementing inclusive practices in my online courses. | 3.63 | 4.42 | +0.79 |

In the wider view, participants’ confidence increased in almost all of the skills areas, which we can attest to with the kind of conversations that happened in small group discussions and work that was presented in individual assignments. Average gains in skill areas where OSU offers other training were lower than the average gains seen in skills areas where there was a gap in professional development that ITO filled.

Yet the skill area where instructors did not seem to increase in confidence (“I can identify systems in society and institutions that inhibit online student success”) exposes the limitations of self-reported confidence levels. This area was one in which many instructors rated their confidence fairly highly on the pre-survey (e.g., a 4 or 5), and then rated their confidence one or more points lower on the post-survey or indicated the same level of confidence as before. This suggests that some instructors over-appraised their skill or confidence at the outset (a possible example of the Dunning-Kruger effect; see Kruger and Dunning (1999), only to discover during the workshop that there was much they did not know about systemic inequities and how that may impact their students in the online classroom. For us, this may actually be somewhat of a positive outcome, warranting additional exploration in future research.

Analyzing Participants’ Action Plans

At the same time that workshop participants submit the post-workshop survey, they also complete a final project that we call a Vision and Action Plan. This assignment prompts participants to document what they have learned in the workshop, identify which tools and strategies will be the most helpful to them going forward, and articulate specific next steps that they can implement (or continue to put into practice).

We used a deductive coding method on all study participants’ answers about strategies they were considering implementing, where instructors were asked to identify at least three strategies. Some instructors chose to cite fewer (as few as 1) and some cited more (up to 7), with an average of 3.4 strategies referenced in their final projects per instructor. Coding was based on an a priori list of strategies that we present in the workshop, though codes were also expanded to include all other strategies mentioned. These additional strategies were often related to specific discussions and conversations that unfolded within a particular cohort as well as external content (resources, references to other workshops, etc.) that was shared either by facilitators or by participants in response to themes and interests that were emerging for the cohort. A total of 34 discrete approaches and strategies emerged from this coding analysis. Table 7.2 presents a summary of the strategies that were referenced most frequently among the 78 instructors who successfully completed the workshop and fully completed a Vision and Action Plan.

| Frequency | Strategy |

|---|---|

| 36 | Implementing the LARA method |

| 23 | Strategic outreach to individual students |

| 20 | Providing transparency in assignment directions (TAD framework) |

| 19 | Including a syllabus statement about the instructor’s approach to diversity, equity, and inclusion |

| 18 | Gathering information about student needs and interests, such as through a beginning-of-term survey |

| 18 | Connecting with students through intentional instructor presence |

| 15 | Diversifying content and materials for wider representation and/or addressing lack of disciplinary diversity |

| 14 | Writing clear guidelines and expectations |

| 10 | Implementing flexible course policies (e.g., for late work) |

| 9 | Communicating time commitment for course and tasks |

| 9 | Seeking additional student feedback |

| 8 | Providing timely communication and feedback |

| 7 | Developing awareness of students’ identities |

| 7 | Clarifying discussion goals (e.g., debate, discussion, or dialogue) |

| 7 | Self-monitoring instructor discussion replies for disbursement among all students |

| 5 | Sharing more instructor information |

| 5 | Adding supplemental and refresher resources |

| 5 | Promoting student connection and teamwork |

| 5 | Self-monitoring instructor language and tone |

The most common reference is to the listen, affirm, respond, and add information (LARA) protocol, which aligns with the early finding that addressing disruptive or biased discussion posts was one of the gaps that prompted the creation of the ITO workshop. Given its introduction near the end of the workshop and challenge to apply relative to some of the other concepts and strategies introduced, LARA was also likely still top of mind when participants completed their final activities that ask them to reflect again on how frameworks like LARA have influenced their thinking about next steps. References to how and where it would be implemented varied widely, however. While the LARA protocol is introduced in the workshop primarily as one way for instructors to facilitate challenging conversations in online course discussion boards, instructors recognized its much wider potential and utility for announcements (such as to help gently correct a wide misconception), in private student feedback (to address a problematic submission or individual comment), and in situations where perhaps nothing had gone awry but they wanted to be cautious of putting a student (or students) on the defensive, whether in front of other students (such as in a discussion forum) or in private communication.

The second most frequent strategy planned for implementation, engaging in strategic outreach to learners, arose out of commentary that suggests an increased awareness of learning management system (LMS) tools as a means for monitoring individual student engagement and progress (e.g., using the gradebook not as simply a functional tool for inputting grades, but as a means for assessing a more holistic picture of individual students’ work since most discrete tasks have associated credit in an online course). Instructor responses indicated a realization that selective outreach can be effective, making this strategy an equity-based approach (spending the time on and with students who need it) that is reasonable to implement in terms of time and effort. Three groups of students came up in the workshop discussions of this planned outreach: disengaged students (those who had missed a key assignment or multiple assignments), struggling students (those who were not passing the course at key milestones in the term and/or who had not passed a high-stakes assessment), and students who were high performing and might benefit from individual praise. Responses suggested a new or reinvigorated sense that instructors are responsible for assessing student progress both generally across the group and individually, and then for making appropriate interventions during a course.

Importantly, what this information was not intended to capture is what instructors were already doing before taking the ITO workshop. Their responses generally indicated new approaches that they had learned and wanted to implement, though some mentioned how the workshop provided research-based justification for things they were doing—or had previously been doing and wanted to return to. Yet the breadth of responses suggests both that instructors were engaged in some of the strategies for which Ecampus did not provide clear training or guidance before ITO was developed, and that there were many different ideas and strategies in the workshop that instructors found useful for their particular contexts.

Tracking Instructors’ Implementation of Strategies

Two academic quarters after instructors complete the ITO workshop, we send a follow-up survey to collect information about their levels of confidence applying inclusive teaching strategies in online courses at that time and to ask them about what practices they have implemented so far.

We used the same set of codes developed for the deductive analysis of the Vision and Action Plan strategies in the analysis of these results but added one new code for an additional strategy mentioned in the follow-up survey. Our response rate was somewhat lower at this stage of inquiry, with a total of 28 valid survey responses. Instructors were not asked to identify a particular number of strategies at this stage, and the number of strategies cited ranged from 1 to 7, with an average of 3.8 strategies cited per instructor respondent.

Table 7.3 gives a summary of the strategies that instructors referenced most frequently two terms after workshop completion, with examples of how those strategies were discussed in their response.

| Frequency | Strategy | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | Including a syllabus statement about the instructor’s approach to diversity, equity, and inclusion | “The syllabus statement really helped! I had a student reach out to me and tell me that English was their third language, and that they were concerned about doing coursework. I told them that English was my second language as well, and they must have read my syllabus statement because they replied in a friendly way and even changed their signature from an anglicized version of their name to their real name, and I felt like I really helped the student be themselves.” |

| 13 | Implementing flexible course policies (e.g., for late work) | “I’ve . . . been more flexible in accepting missing work, which I have found students respond to very well and are often surprised to have the opportunity. I’ve been able to help at least a couple of students pass and graduate because of these strategies.” |

| 11 | Diversifying content and materials for wider representation and/or addressing lack of disciplinary diversity | “I increased the number of underrepresented scientists I include in my ‘career profiles.’ I have had a few students comment that they appreciated seeing people who looked like them in these profiles.” |

| 7 | Gathering information about student needs and interests, such as through a beginning-of-term survey | “Who’s in the Room survey is a useful reference.” |

| 6 | Providing transparency in assignment directions (TAD framework) | “I’ve . . . revised some language in the assignment introductions to explain their purpose. . . . Students have appreciated the improved clarity in the assignment prompts.” |

| 5 | Developing awareness of students’ identities | “These strategies are not new in my classroom, but they have more structure and intent behind them now, and students feel seen. In a course last term, a student taking a class to transfer the credit back to his home university noted how inclusive and diverse my classroom was as opposed to his classes at home. He mentioned specifically my syllabus statement about diversity/inclusion, my suggestion to note pronouns on Zoom and in Canvas, the wide range of topics about LGBTQ and POC individuals as part of our ‘normal’ content (i.e., these weren’t ‘add-on’ topics) and my repeated stated commitment to community building.” |

| 5 | Writing clear guidelines and expectations | “Greater overview/explanation of course expectations and goals, as well as my teaching style . . . these strategies have worked well.” |

| 5 | Connecting with students through intentional instructor presence | “I continue to provide feedback to each student (addressing them by name) on their assignments. This is an important way to maintain communications with students and encourage their engagement and performance.” |

| 5 | Engaging in strategic outreach to individual students | “Nudging seems to work, as the quality of work seems to have improved compared to past year.” |

| 5 | Promoting student connection and teamwork | “I’ve implemented more group work in the beginning of the course especially, to have students work together over a series of scaffolded, low stakes assignments to achieve the close reading skill set that is so difficult for most students to learn.” |

One of the two most cited strategies is adding or revising an inclusion statement for the syllabus, since workshop participants draft, peer review, and rework their statement as part of the workshop. In most cases, instructors who complete the ITO workshop would be prepared to simply add that statement to their syllabi thereafter, so it is an easy next step in terms of implementation. During the workshop, instructors often question whether students are reading the syllabus and whether they will see the inclusion statement, and feedback from this survey suggests some success in using that key document to help set the tone for how the instructor approaches equity and inclusion considerations in their own online classroom.

Implementing more flexible course policies was the second most cited strategy. This strategy was the subject of much debate across most cohorts and received both positive and negative feedback in this later survey, primarily because some instructors believe too much flexibility can create problems for students making adequate progress in the course. Take this example:

I am not certain that the ability to skip some assessments has helped more than it hurt. A few students had mid-quarter crises, and the flexibility helped them. Several other students used the flexibility to essentially skip the first three weeks of the course, and started taking assessments in the fourth. They got kicked in the teeth by the exams, fell far behind, and ended up either dropping the course or earning a poor grade.

While instructor respondents overall indicated that a degree of flexibility is important to support students when unexpected life, work, or family emergencies arise, they also believed that too much flexibility can encourage students to get off track. Many of our conversations with instructors during the workshop have centered around identifying an adequate amount of flexibility—a level that honors students’ complex and challenging commitments but helps to prevent unnecessary (often late and without tuition remission) withdrawals or failing grades.

What is intriguing about these responses is that they do not strongly correlate to the strategies mentioned in the Vision and Action Plans. The use of the LARA method, for example, was cited only briefly by three instructors. While it is possible that some instructors may be using parts of the LARA method in their online course facilitation without calling attention to it in their survey responses, these results suggest that other strategies end up being used more frequently or with more perceived impact once instructors take what they have learned from ITO training back to their online classrooms.

Facilitator Observations from ITO

We are grateful to have learned so much from instructors over the course of facilitating the ITO workshop. The qualitative and quantitative data collected across our cohorts is rich but does not fully capture the profoundly meaningful conversations that unfold within each cohort and the connections that instructors make with each other along the way.

For others working in faculty development who might be interested in starting or expanding opportunities in inclusive online teaching, we want to offer the following additional observations about what to be prepared for and what has worked best, based both on our experiences and participant feedback.

This journey is personal for instructors, and they each have a unique path. Instructors who opt into this kind of workshop usually share a common commitment to student success, but they often begin from different places and ultimately have different destinations. We have seen that their journeys vary with respect to their knowledge about the diversity and needs of their online students and the depth of their thinking about what is possible in their classrooms in responding to student diversity and needs. These differences in approaches and paths also reflect a variety of instructor identities and how they deepen their understanding of how their identities are reflected in their online teaching during the course of the workshop. Our workshop has served instructors who teach social justice themes and who are deeply invested in those topics as well as instructors who initially believe that their disciplines are not affected by inequities and that they are grounded in universally objective truths. Instructors who hold a wide variety of identities have participated in our workshop, but OSU is still a predominantly white institution in terms of instructor demographics, and our workshop cohorts reflected those demographic realities. Flexibility both in content and facilitation methods can accommodate those different instructor needs so that workshop participants find places to engage that feel meaningful to them and also so that they help to guide each other (which we will address further in the next section). Take, for example, the prompt structure “I used to think . . . now I think,” which we use in discussions during the workshop and to help participants capture changes in their mindset or approach as part of their final Vision and Action Plan. Each of the five below responses capture different but equally valid reflections on participants’ transformed thinking:

I used to think that many of the students in my online courses took these mainly out of convenience rather than need. I held the perspective that many students could and maybe should take the class in person, but that they signed up to take the online version to have a more flexible schedule. I also used to think that students believed online learning to be easier or less work than in-person classes. I now have a very different perspective about online learners. I don’t think many take Ecampus courses out of convenience. Actually, ITO helped me understand that Ecampus courses really take a lot of commitment, time management, and self-paced (but not lax) learning. . . . I now understand just how committed online learners are to their education, and how much they are likely juggling in their lives. I have been teaching an Ecampus course while enrolled in this workshop and honestly my perspective has shifted about my current class in really positive ways, which has resulted in me being even more engaged with my students beyond just grading their assignments. I feel like I have received some excellent feedback from my students as well.

—Graduate student in public health

I used to think that I could hide in the shadows and that my students would intuit my good intentions. Now I think I need to clearly define and hold the classroom space for my students. I need to be present to make everyone feel safe and welcome. Early in this workshop, I said to everyone that I create a welcoming, easygoing persona in the classroom. As I have been making some major edits to my courses in preparation for spring term, I am finding that the way I present myself is inconsistent. I always accept late work (my boyfriend thinks I’m a pushover), but I don’t make that clear to the students in any way. Instead, I have statements in my syllabus that make it sound like someone needs to die in order for me to accept late work. What I have learned from this workshop is that my words matter. The way I talk about late work in the syllabus could make a difference between a student giving up and dropping the course . . . versus a student knowing that I am a safe, compassionate person who has their success as my highest goal.

—Instructor in forestry

I used to think it wasn’t my place to share my personal beliefs or values in the classroom. Now I think I owe it to my students to do a little more in this area. While I still believe this is a tricky topic, I am starting to see how my position of power in the classroom is important for setting the tone, and this can be done in part by sharing more values-driven material. What I share and what I don’t share both send a message. The week 1 topic of “The Role of Faculty Identities” had me thinking a lot that first week about what we as instructors can and should share. So many of us seem to work hard at being objective, which results in us sharing less personalized parts of ourselves, which I believe creates distance between us and our students. So I will work to share more of myself in ways that are supportive of my students.

—Instructor in business

I really appreciated the opportunity to think more about the role of culture in online learning. I had not really thought about the ways that culture could play a role in how students learn best, and the types of barriers they might face in educational settings. While I have done work around universal design with the online courses I have developed, Module 1.4 [“Cultural Awareness”] really made me think about how my students experience my online classes and the unique goals they may have for learning. For me, universal design had previously been more about creating spaces for students with differing abilities to be able to learn effectively. I hadn’t really used that term to think about students with different approaches to learning or goals for learning. I really appreciate the Cultural Constructs of Teaching and Learning table that explains specific ways learning can be integrated (versus the individuated end of the spectrum). This information will be helpful as I continue to design and teach online classes, because it gives me more food for thought about how to create a truly universal design that provides space for all of my students to learn in a way that best meets their needs.

—Instructor in human sciences

This [prompt] is something I’ve really had to think about. I’m not sure that the workshop changed the way I think about online students. I’ve taught various university classes and labs for over 11 years and have taught online for over 8 years. As someone who is passionate and interested in teaching, I’ve worked hard to improve every single term. My teaching and classes have evolved in that time. . . . If I had to choose something that has changed for me based on this workshop, it is this: I used to think that in a science class, promoting diversity through diverse teaching methods, activities, and interactions was enough without explicitly addressing diversity at any point. Now I think that is not enough. I need to actively address diversity and inclusivity head-on in my syllabus and introduction. None of my syllabi have yet included a diversity and inclusivity statement, but that will change.

—Instructor in agricultural sciences

These responses represent instructors at various stages of teaching experience, from a new instructor who learned a lot about online student demographics and needs to experienced teaching faculty who were prepared to think about not just teaching inclusively but also addressing DEI issues in their course explicitly. Their reflections indicate different points of beginning and ending with respect to their thinking during the ITO workshop, but each of these instructors took away something meaningful that will inform their next steps.

Peer-to-peer connections are vital. Creating peer-to-peer connections through discussions and feedback activities are invaluable in a workshop on inclusivity so that many perspectives are discussed, especially given the diversity in discipline and career stage that we have seen among our cohorts. The ITO workshop features weekly discussions and two peer feedback activities: one to gather feedback and revise a DEI syllabus statement, and one to workshop instructor participants’ draft Vision and Action Plans. Instructors usually learn as much from each other as from facilitators (if not more), especially when given the chance to see different examples (e.g., syllabus statements) and applications of strategies (e.g., across or within discipline). Instructors sharing their approaches and experience may even carry more weight than the workshop content or facilitator feedback and therefore can be more persuasive in encouraging peers to adopt inclusive teaching approaches. Oftentimes such sharing and learning were central to the “I used to think . . . now I think . . .” responses in the Vision and Action Plan, as demonstrated in the following responses (emphasis ours).

It’s embarrassing to admit, but I have to say that I used to think my program was more “advanced” in its commitment to diversity and inclusion in online teaching than other programs at OSU. From interacting with the facilitators of this workshop and especially with my peers, I realize that this assumption was very misguided; in fact, instructors from all kinds of fields are highly committed to principles of just and inclusive teaching online, and many of them have different knowledge and skills that they have generously shared in this workshop. For instance, one of my peers offered a useful framing of students’ contributions to online courses as a form of labor; although I think about the concept of labor in almost every facet of my life, I had not applied this idea to my Ecampus courses. I will be thinking more about how to apply this framing to my syllabus so that we are collectively discussing the sharing of labor in more intentional ways. I think this is especially important in online learning settings, because I’ve found that students who are brand-new to online classes sometimes approach the class individualistically. It often takes several weeks for them to build relationships with their more experienced peers, which help[s] to reveal how we all have responsibilities to each other and share in each other’s learning.

I used to think that being an online teacher was somehow less valuable than being a face-to-face teacher. . . . Now I realize that my teaching is valuable, and my importance as a teacher to my students is not somehow lessened by being in an online classroom. Specifically, in Module 1.7 [“Beliefs about Online Learning and Online Students”], we watched videos about all the different types of students who learn through OSU’s Ecampus, and how much they value the availability of high-quality online courses. It was enlightening to see/hear that students come to OSU Ecampus programs for a variety of reasons, including issues of access. As a . . . disability studies researcher, I know how important social and academic flexibility is for students in nontraditional circumstances. Yet I have been undervaluing my own impact as an instructor who can help facilitate increased flexibility and access in an academic environment. One of my small group colleagues . . . noted that it is important to recognize the value of my efforts to support students and help them realize success and optimize well-being.

Even though I was aware that many of my online students were current professionals who had families and busy lives, over the course of this workshop I have realized that I was not really giving those facts about their lives full consideration and was thinking about them more as full-time students, similar to those I have taught face-to-face in the past. Over the course of the workshop, listening to other instructors’ experiences and reading about the various tools and approaches, I’ve come to realize that I need to give my students more “benefit of the doubt” while still holding them accountable to the requirements of the course.

When a connection to workshop peers was mentioned, the circumstances were usually recalled in some detail—who said something memorable, when, and how it changed their thinking. Note, too, how the examples above suggest the notion of peer influence in coming to see why and how inclusive teaching practices should be implemented. Likely for all of these peer-to-peer benefits, we have had requests to extend this kind of learning community into an ITO alumni community of practice because the connections with peers and sharing of ideas were so invigorating for participants.

Facilitation is time- and energy-consuming, so more than one facilitator is helpful. Chapter 6 addressed how much emotional labor is required for online instructors to facilitate a course that involves social justice issues, and likewise a lot of emotional labor is involved in facilitating a workshop on inclusive teaching practices. Having multiple facilitators to share that workload is ideal and allows the facilitation team to share a wider variety of perspectives. We made an effort to rotate which facilitator gave feedback to which set of participants each week so that instructors could be exposed to different ideas and even approaches to facilitation and feedback during their workshop experience.

Share inclusive practices outside of a deep-dive workshop, too. While we have been running the ITO workshop and the associated research project, we have strategically shared pieces of the workshop in other professional development contexts. As one example, key tenets of inclusive teaching are represented across the OSU Ecampus Online Teaching Principles, and these principles form the basis of new online instructor training at OSU. We aim to counsel instructors early about why these principles are important, how and when to put them into action in facilitation, and how to make thoughtful choices about how to spend their contracted time in facilitating an online course. As another example, instructional faculty across our campus who supervise and mentor graduate teaching assistants (GTAs) often request custom trainings for the GTAs who teach online in their respective departments, and we have created mini-trainings to address topics of interest or that these early-career teachers expressed that they needed, like how to respond to disruptive discussion board posts in online courses and tips for structuring helpful student feedback.

Faculty development on equity and inclusion is contextual and should be responsive. We are fortunate to work at an institution that sees this work as mission-critical and to have colleagues around campus who regularly share their expertise in applying equity and inclusion tactics in the classroom and workplace. When instructors participate in ITO, we are usually not the first or the last equity or inclusion workshop that they will take at our institution. A number of academic units at OSU have recently implemented new position description language to set expectations that instructional faculty engage in professional development related to equity and inclusion and to commit to implementing best practices for inclusive teaching in the classroom, which has encouraged participation in ITO and raised awareness that equity and inclusion are a responsibility for all teaching faculty in higher education. Through our initial findings, we see instructors more prepared now to engage and have conversations about how systems of inequity and bias impact our students than they did at the time of ITO’s initial launch in 2020. We attribute this both to OSU strengthening programming and support teaching excellence and to instructors becoming more attuned to student needs during and after COVID, since the pandemic prompted instructors to listen to what was going on in students’ lives inside and outside of school in ways they often had not done previously. ITO will continue to be responsive to instructor needs at OSU over time. Likewise, these types of trainings will necessarily need to be catered to your institutional context, and we acknowledge that some institutions no longer have staff or permission to run these trainings at all. We hope that our suggestions throughout this text have provided insight into how to do the good and necessary work of inclusive online teaching in any context, including framing of the “why” (student success) and the “what” (vocabulary for the purpose and the strategies)—all in light of the fact that this kind work aims to support students success.

Conclusion

Inclusive online teaching is ideally sustained and advanced within a community of like-minded practitioners. Trusted colleagues among instructional faculty, instructional designers, faculty developers, academic advisors, and student affairs staff can help to identify barriers, brainstorm possible solutions, and perhaps most importantly help us see our own gaps in awareness. We hope that you have—or that you will seek out or build—such a community because we engage in this work of access and inclusion better together.

We want to end where we began, affirming that inclusive online teaching that seeks to welcome, value, and engage each student is effective online teaching. It is challenging, complex, and requires an ongoing commitment to flexibility, adaptation, change, and most of all, learning from and listening to online students so that they can be supported and successful. Our goal is that this book has inspired you to reflect and find new ways to support online students within your particular spheres of influence, and that you have found useful tools and frameworks as you work on next steps and implementing your inclusive online teaching plans. We are all agents of change and can always continue to hone our approaches to providing inclusive online education for our students.

References

Kruger, Justin, and David Dunning. 1999. “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (6): 1121–34. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121.

- An 85% overall score in the workshop indicates a “completion” for general record-keeping purposes but may mean that an instructor did not fully complete a pre- or post-survey. Those records are excluded. ↵