1 Learning Frameworks for Inclusive Design (and Teaching)

Introduction

With the premise that course design always precedes course facilitation, we begin the book with a chapter about inclusive online design frameworks to set the foundation for the remainder of our focus on online course facilitation. Course design and facilitation choices overlap and are closely intertwined; ideally, they also complement each other. For example, it is hard to imagine planning out effective instructor engagement with students without examining the methods or frameworks adopted in the design phase for instructor–student interaction. This chapter presents a curated set of learning theories and design frameworks that are broadly connected to notions of student inclusion. Such theories and frameworks work well in parallel with the facilitation strategies we suggest in other chapters. Since instructors need to explicitly know and apply theoretical frameworks about teaching and how people learn (Ally 2008), we highlight key theories and frameworks related to design that ultimately have inclusive facilitation implications.[1]

Many online instructors are able to design and modify their courses, but others may be handed a predesigned course to teach that they may or may not be able to change. This chapter can be helpful in any of these three situations:

- If you are designing or modifying your own course, use this chapter as a guide to your initial design or to your revision choices. Through subsequent chapters, you can select inclusive facilitation strategies and actions that align well with your course design.

- If you teach a course that you did not design and are able to modify it, use this chapter as a means to analyze the course that was given to you. Identify what frameworks or theories you can see at work in the course, then decide if you want to keep those design elements, deepen them, or change them. Through subsequent chapters, you can select inclusive facilitation strategies and actions that align well with your course design.

- If you teach a course that you did not design and you are not able to modify it, use this chapter as a means to analyze the course that was given to you. Identify what frameworks or theories you can see at work in the course. Through subsequent chapters, you can select inclusive facilitation strategies and actions that align with the existing course design, and then consider strategies that can help personalize your teaching within the context of the pre-designed course that was given to you to teach.

Integrating Design and Facilitation with Student Feedback

One of the initial challenges of integrating online design and facilitation is entirely logistical: we learn over time what works best for delivering a course or a program to diverse online students. Say you are designing a brand-new online course or program and are unsure about who your students will be and what needs they will have. Sometimes the integration of design and facilitation choices will only become clear later, after a continuous improvement process —such as when you solicit concrete student feedback and pair that with your own observations about student progress across activities and assessments. End-of-course evaluations might also reveal gaps or problems that can be addressed with course design revisions and/or specific teaching interventions.

Soliciting student feedback beyond end-of-course evaluation processes is one way to address the challenges of integrating design and facilitation effectively. Student feedback is valuable to enhance a course to better meet the range of student needs. If you are able to do so, consider soliciting feedback from your students specifically about how they experience the course in terms of its design. End-of-course evaluations rarely elicit this kind of specific feedback, and students may have forgotten by the end of the term how a design element earlier in the course impacted their experience positively or negatively. As part of an Inclusive Excellence (IE) initiative at OSU Ecampus, a Faculty Toolkit for Student Feedback Survey was designed and tested for the purpose of collecting student feedback about course design across an academic term. Two sample surveys are included: one meant to draw out feedback about course design generally, and one inquiring about multimedia elements specifically. We encourage you to try out the recommended approaches offered by Ecampus instructors who participated in the pilot of that project. This kind of survey framework can be particularly helpful when a course is first designed and launched, or when revisions have been made and student feedback would help to confirm choices or suggest new possibilities for continuous improvement.

Frameworks and Considerations for Inclusive Design and Instruction

Inclusive design and instruction are informed by multiple theories and practices that contribute to creating supportive learning environments. There is no single, unified learning theory that informs and guides online learning design (Ally 2008), nor a single set of practices that can help to create an inclusive online classroom. Inclusive design practices are rooted in a number of key theories and instructional approaches that postulate how to “motivate learners, facilitate deep processing, build the whole person, cater to individual differences, promote meaningful learning, encourage interaction, provide relevant feedback, facilitate contextual learning, and provide support during the learning process” (Ally 2008, 18-19). The recommendations derived from the selected learning theories and design frameworks discussed here complement the facilitation strategies that we recommend throughout this book because they focus both on the diversity of learners and key characteristics that often define online learners (e.g., that they are typically nontraditional adult learners). We offer overviews and examples of the groups of theories and frameworks over the remainder of this chapter.

An important caveat: these theories provide only partial views into the complexity of learners and learning, so they are not “universal” and are subject to critique. Parson and Major (2021) argue that traditional learning theories (e.g., behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism) fail to account for the full range of student difference within the academic environment and instead have been used to reinforce existing societal inequities (e.g., unequal access to resources and support). This argument points to the prominence of Western ideologies in teaching and learning, particularly assumptions about adult learners based on white, elite, male, and decontextualized learning experiences that ignore other possible identities of learners. In addition, traditional learning theories promote Western-centric ways of knowledge and learning, overlooking alternative learning methods—particularly Indigenous and other non-Western approaches—that could support students from different cultures, with different values and needs (Parson and Major 2021). In response to the limitations of a single theory to design learning experiences that consider each unique learner and their differences (individual and contextual), it is important to weigh both the affordances and constraints of each framework. What these frameworks ultimately offer is varying degrees of insight into how specific situations and conditions foster and scaffold learning, and therefore potential applications to assist instructors in proactively addressing barriers to learning when designing their online courses.

While we present frameworks individually in this chapter for clarity, another important critique of learning design theory underscores the potential dangers of selecting and integrating just one. Costanza-Chock (2020) argues that using a single-axis framework and universalist design principles can “erase certain groups of people, specifically those who are intersectionally disadvantaged or multiply burdened under white supremacist heteropatriarchy, capitalism, and settler colonialism” (19). Fundamentally, universalist design practices can overlook the unique, multifaceted, and intersectional experiences of learners. These types of design practices can then perpetuate inequities and further disadvantage already marginalized individuals (e.g., Black people, people with disabilities, people who identify across the gender spectrum) because the task of envisioning a “universal” learner profile tends to re-center dominant identities and perspectives. Consider, for instance, how learners may be envisioned at the stage of course design or revision. The breadth of learner diversity may not be accounted for if instructors and/or instructional designers revert to thinking about the “typical” or “average” student in the course (Rose 2015); using well-crafted, data-informed student personas may help to redress that assumption (McBrien 2020). Additionally, the language of universal design is often oriented toward addressing accessibility alone, when in reality accessibility is just one element of designing for a diverse audience (Garcia 2019).

Lastly, an important critique about online learning design calls us to interrogate the structural biases that are inherent to uses of educational technology. Benjamin (2019) argues that the biases held by technology designers may transfer to the tools and systems they create, and “in the face of discriminatory effects, if those with the power to design differently choose business as usual, then they are perpetuating a racist system whether or not they are card-carrying members of their local chapter of Black Lives Matter” (Benjamin 2019, 58). The socioeconomic and racial inequities we see in society can be reproduced in the classroom when the instructional systems, technologies, and practices are assumed to be neutral. In reality, these are not. Digital tools, including emerging technologies, can expose people to increased racial biases and stereotypes through design. Take, for example, artificial intelligence and facial recognition applications—used in online testing and proctoring—where the algorithms and data used in training them include the biases held from the software designers, perpetuating racism and gender bias (Buolamwini 2016; O’Neil 2016). Benjamin (2019) highlights the double standard in facial recognition technologies that, on the one hand, are designed to ignore Black people and therefore create more inequities for these individuals and, on the other hand, create hyper-visibility, exposing them to stereotypes and hyper-surveillance practices for social control and exclusion (e.g., over-policing Black people). Adopting and implementing biased educational technologies in the classroom might impact students in more than one way. For instance, these tools can perpetuate racial and ethnic stereotypes, compromise data privacy, limit exposure to diverse voices and experiences, provide inaccurate content, erode student trust with instructors, and raise ethical and legal concerns. Thus transparency with students is a necessary measure to show how these tools are used to support learning, providing students with alternatives if they express concerns about using the tools while also helping them develop digital literacy.

These critiques aim to highlight the complexity of learning and the conditions that impact it; keeping them in mind can help you make decisions for a more learner-centered environment, both in your online course design and teaching approaches. The following sections describe the insights from the learning theories and design frameworks we have curated, emphasizing their learner-centered focus and goals for wider inclusivity.

Supporting Learning through Social Interaction

Learning is fundamentally a social process where knowledge is created through interaction with others. In this section, we describe three learning frameworks that can help you (re)imagine your course as a social space for learning, active participation, and collaborative knowledge construction. Socioconstructivism emphasizes an individual’s construction of knowledge through their social interaction and collaboration with others—a situated, “participatory” view of learning development that opposes a view of learning as unsituated knowledge “acquisition” (Barab and Duffy 2012, 32). As originally postulated by Bruner (1960), learners construct new knowledge upon previous foundations and engage actively with content and activities (e.g., problem-solving). In addition, students are expected to transfer their knowledge and skills to other situations—to apply what they learned in the classroom to future study, life, or work environments beyond their disciplinary interests. Students also need to be trained to understand the “underlying structure or significance of complex knowledge” (Bruner 1960, 6), which means understanding the interconnection between content and complex concepts and why they matter. In short, for knowledge construction and transfer of learning, students need to see the connections between their prior knowledge and new, highly related knowledge through supportive systems based on existing cognitive schemas.

Bruner (1960) suggests that one way to achieve transfer not only of knowledge and skills but also of principles and attitudes is through discovery learning. In discovery learning, students are actively engaged in activities that allow them to experiment and discover new ideas and concepts by themselves. These activities might include inquiry-based learning, problem-solving, project-based learning, experiential learning, and other approaches where students ask and answer questions, work on hands-on activities, conduct research and experimentation, apply or transfer what they learn to other situations or problems, and connect the knowledge and skills they learn to personal experiences. In addition, in discovery learning, the course curriculum considers fundamental notions of and contemporary advances in the discipline for deep comprehension and for transfer, so the content needs to be structured for deeper cognitive processing and complex concepts need to be broken down into more manageable pieces. In this framework, learning occurs meaningfully as students engage in social interactions with peers, and the instructor plays a particularly important role in helping students to make sense of the connections they discover.

Additionally, the socioconstructivist approach underscores that knowledge is built through interactions in the learning environment. It emphasizes that the construction of knowledge does not happen in isolation but in social interactions (Bruner 1960), specifically in the relationships between learners and learners with their instructor. In this context, students become co-constructors of knowledge, building knowledge together upon their individual and collective prior knowledge, lived experiences, and relationships with peers. The learning environment serves as a social space where students and instructors engage in active participation, communication, and dialogue. These interactions are fundamental in the online classroom because they allow students to express their ideas, challenge each other’s perspectives, and negotiate meaning, therefore constructing knowledge collaboratively. In addition, instructor participation is essential in online classrooms, as students often require guidance from a more knowledgeable individual (usually the instructor) to cement foundational knowledge, discover new concepts, and integrate new knowledge (Vygotsky 1978). Collaborative learning, which draws heavily on socioconstructivist principles, is considered a high-impact practice for online education and a potential avenue for meeting the needs of historically underserved students in higher education (Robertson and Riggs 2018).

As you begin your course design, revision, or analysis, consider how learning is constructed and whether it could more fully or actively involve community. Focus on the kinds of independent activities that are often incorporated in online courses: reading textbooks, articles, and the like (alone); watching lecture videos (alone); completing homework or weekly assignments (alone); conducting library research (alone), and so on. Contrast those activities with the types of interactions and collaborative activities that are possible in the online classroom: discussion forums, peer and instructor reviews, group projects, think-pair-share activities. In online courses the instructor and other students actively participate in the learning process by offering feedback, engaging in conversation, and being a sounding board for developing knowledge and ideas. For example:

- Identify the choices you can make to (re)design activities to enhance interaction and scaffolding, such as structuring a group project into stages and enabling a Q&A forum for students to post questions about the project.

- When (re)design is beyond your scope of work, consider adding to the course recommended ungraded (or extra credit) discussions for students to share ideas, elaborate on concepts, or discuss challenges.

Cultivating these types of supportive social spaces and activities can help students be successful in their learning journeys.

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework emphasizes learning in and through community. It extends socioconstructivist theory to include a three-part model that describes how individuals “collaboratively engage in purposeful critical discourse and reflection to construct personal meaning and confirm mutual understanding” (CoI Framework Athabasca University n.d.). The emphasis on community and dialogue makes this framework particularly important for both design and instructional considerations related to inclusivity. Originally posited by Garrison et al. (1999) as a framework for designing and analyzing purposeful online classroom interactions, the CoI framework is visualized as a three-circle venn diagram to illustrate the interconnections between all participants’ social and cognitive presence as well as the instructor’s teaching presence. The three parts are defined as follows:

- Social presence refers to “the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop interpersonal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities” (Garrison 2009, 352).

- Cognitive presence is defined as “the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse in a critical community of inquiry” (Garrison et al. 2001, 11).

- Teaching presence includes the design and organization of the learning environment, facilitation, and direct instruction (Stenbom and Cleveland-Innes 2024, 8-9).

These three types of presence are important to consider in terms of how discourse unfolds and how knowledge is built, but also because the CoI framework suggests specific design-related choices that will ultimately support these interactions within a learning community. For example, “a collaborative Teaching Presence is made explicit when the teacher designs learning activities or courses where students may design, organize, facilitate, direct, and/or instruct themselves and others as they collectively build on the perspectives of teachers, materials, and other students” (Stenbom and Cleveland-Innes 2024, 9). To prime the learning community for engaged dialogue in discussions, instructors designing or redesigning a course might consider scaffolding low-stakes discussions activities early in the term to practice the kind of interaction that will best support learning; design can also take into consideration how to support the kind of “intellectual leadership” that instructors need to bring to discussions (Shea 2024, 76-77). The CoI model presents a particularly strong case for the deep interconnections between learning design and facilitation while staying rooted in a student-centered model for online education; however, this model has not fully accounted for cultural differences that may exist in how learners understand their own role and their instructor’s role (Wendt et al. 2018). Careful scaffolding is needed to prepare students to participate in the kind of dialogue that furthers learning in a particular context (see chap. 5 for a detailed discussion of conversation types), as is thoughtful facilitation to support students along the way.

As you make choices in the course—whether for (re)design or facilitation only—keep in mind the interconnections promoted by CoI, and identify where in the course activities engagement can be enhanced. For example:

- Consider (re)designing collaborative group activities to include more scaffolding. Provide students with an opportunity to introduce themselves to the group and build rapport (developing social presence) early in the course, then identify clear outcomes for collaborating on group tasks (developing cognitive presence). Encourage students to build ideas together as they learn from one another, and demarcate a clear role for yourself as the instructor and your approach to encourage engagement and learning.

- If you cannot adjust the course design, consider organizing frequent group check-ins throughout the term, either as office hours or as survey-style reports where you can learn more about how group work is unfolding and where you need to provide additional scaffolding and feedback.

Further, to account for the cultural context where learning takes place, many theorists, but most famously Vygotsky (1978), have posited that learners construct knowledge through culturally mediated interactions with others who have more knowledge. Sociocultural learning theory explains the cognitive development of young learners through the concept of “zone of proximal development,” which is essentially “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (79). This concept explains that a learner can perform more challenging activities when given adequate guidance from a more knowledgeable facilitator, usually the instructor or teaching assistant, than they can achieve independently.

In sociocultural learning theory, language, dialogue, and symbols—all cultural elements—help mediate learning, and therefore these tools shape how learners experience the world and solve problems. For adult learners from diverse backgrounds and with varied lived experiences, sociocultural learning theory can inform teaching practices that support effective collaboration between students where they learn from one another, such as in a discussion board, thereby deepening their understanding and applying knowledge to new situations. In addition, this theory can inform how to adequately scaffold the learning process to help students gradually process more complex concepts or work on mastering complex skills. For example:

- In (re)designing your course, consider small-stakes or larger-stakes activities that help students to learn from and with each other, such as team activities or assignments that engage students in collaborative learning. Set the tone of teamwork by asking students to introduce themselves and share their interests, abilities, backgrounds, strengths, weaknesses, communication and work styles, and previous experiences. This activity may surface individual strengths for the team to lean into, and their perspectives may be shaped by interacting with each other. A second part of the team-building activity can ask students to discuss “What if ?” questions, such as “What if a team member does not like the topic of the project?” or “What if a team member struggles with their assigned role?” Ask the team to create a success plan that addresses communication, contributions, project/time management, disagreement rules, individual and team accountability, roles and responsibilities, as well as their experience with the prompts and how that discussion helped them come up with their plan.

- In facilitating the activity above, be prepared to support students’ engagement in dialogue and work with teammates by providing a rationale for the value of high-performing teams and how their individual strengths will make the team successful.

Shaping Learning through Digital Connectivity

Connectivism emphasizes the importance and influence of social, personal, and technological networks in constructing and sharing knowledge as well as in the formal learning process. This theory of learning posits that technology is a key element in the learning process (Siemens 2005) and that learning results from the interactions an individual has through interconnected networks (Downes 2022). Siemens sees connectivism as a cycle of knowledge development that begins with the learner and their personal knowledge. This knowledge then connects to networks or environments to which the learner belongs, and in turn these networks connect to others that offer more information and knowledge. Thus learning is no longer an activity done in isolation; it is a complex and extended process altered by social networks and technologies.

With rapid developments in technology and knowledge, learning can happen in both formal and informal settings, such as communities of practice, personal networks, work environments. In an interconnected world and with the abundance of information, Siemens (2005) argues that it is paramount to analyze the value of what is being learned and to develop critical skills to appraise sources of information—that is, we need to act beyond our immediate learning environments by “drawing information outside of our primary knowledge” (2). The central point is to support learners in making meaningful connections across multiple sources and networks of information, identify relevance and patterns, and evaluate sources. An important implication of connectivism is that the learning process is not completely within the learner but can also involve external sources, such as an organization or a database. Emphasizing process over outcome, Siemens (2005) notes that “the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing” (5).

For online instructors teaching in digital environments and serving diverse learners, connectivism offers an important view of the teaching and learning process, how learning occurs, and how it is delivered and assessed when technology plays such a key role. Downes (2022) argues that connectivism focuses on understanding a “person’s capacity to live, work, and thrive within a wider interconnected community” (84). While Siemens views learning in connectivism as personal and social networks connecting with each other in a cycle, Downes views the personal and social networks as separate but interacting perception and communication, much like neural and social networks interact. For Downes, knowledge develops from the interactions and practice within the personal and social networks (human and nonhuman), leading the networks to grow and also become more refined. In an online learning environment, this means that an inclusive design strategy can integrate and prompt these interactions through modeling, demonstrations, and practice to help students navigate and leverage their community memberships within and beyond the classroom and educational institution. Consider the following recommendations:

- As you (re)design your course, you might identify where students can benefit the most from engaging in interconnected communities, both academic and nonacademic. For example, in a computer science class, students work in groups to solve a complex coding problem; they could use a variety of resources including online forums, coding communities such as Stack Overflow, or collaborative developer platforms such as Github to gather snippets of code, ask questions, and develop the code collaboratively. Students could seek peer feedback by discussing their progress in solving the problem with other class groups before they submit their program to the instructor for feedback. The framework of connectivism may also encourage inclusive course design choices because of the focus on students’ own knowledge and networks (digital or social), which can help give them agency and foster autonomy.

- If a predesigned course that you are given lacks opportunities to leverage social, personal, and technological networks, you might consider how to integrate interconnected networks and learning experiences by providing additional, recommended sets of resources and connections to communities that students can explore and use to complete their assignments.

Considerations Related to Generative Artificial Intelligence

The connectivism framework also provides a helpful lens for thinking about the implications of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) tools—designing them in, designing them out, or a combination of both approaches—in the context of an online course. On the one hand, this framework helps us to situate GAI tools as just another technological network that can be used or not used in the learning process. The framework also reminds us that we can purposefully and ethically use digital technologies in educational settings by way of decision-making tools that predate the emergence of GAI (see OSU Ecampus’ decision tree, influenced by Institutional Review Board, or IRB, protocols that have been around for many years). On the other hand, connectivism prompts us to acknowledge the complexities of how student learning is affected by the use of GAI. Instructors and students have voiced concern that GAI will undermine student learning by effectively outsourcing the recall of knowledge, analysis of information, and creation of new information and deliverables in the course to algorithms (Gunaratne 2024; Zhai et al. 2024). Algorithms have been shown to be inaccurate, unreliable, and biased (Mei et al.a 2023; Nicoletti and Bass 2023; Greene-Santos 2024) and to have deep ethical problems related to their training and refinement (Gaonkar et al. 2020; Chen 2023; Hao and Seetharaman 2023). Furthermore, current GAI tool queries have a significant footprint in terms of climate impact (Bender et al. 2021; Ren and Wierman 2024; Thomas et al. 2024).

Uneven access to these tools—many of them require a strong, active Internet connection, many of the best-output GAI tools are not free, and free tools generally incorporate user data into the model—presents a host of equity problems that could raise barriers for students rather than support their learning. Yet a survey of Ecampus students in February 2024 found that 62% of undergraduates, 70% of postbaccalaureate students, and 83% of graduate students were “somewhat interested,” “interested,” or “very interested” in receiving guidance from their Ecampus instructors about how to use GAI in their coursework (Dello Stritto et al. 2024), suggesting that students are aware that these tools may have utility in their learning, whether they apply immediately in the context of coursework or in preparation for their careers and lives beyond school. There are no simple or straightforward solutions for how to address GAI in courses, but connectivism and other lenses for inclusive design and teaching may help you to work through those considerations with equity and inclusion in mind.

Promoting Student Success through Empowerment

The frameworks in this section aim to challenge systemic inequities and power structures within and outside the classroom. Central to these frameworks is student empowerment: giving students voice, celebrating and engaging their backgrounds, acknowledging lived experiences, and welcoming their varied ways of being, knowing, and learning. These frameworks can help delineate strategies to empower students in their academic achievement and sense of belonging—ultimately helping to build strong student–instructor relationships in the online classroom.

First, critical pedagogy seeks to examine and challenge traditional power structures in the educational landscape, empowering students to become transformational forces in their own academic journey. Drawing on Freire (1970), critical pedagogy imagines learning as liberatory practices that promote critical consciousness-raising through a dialogic model, positing students as active participants who are encouraged to question social, political, and economic norms. Contemporary scholars of critical pedagogy challenge unexamined teaching practices and expand the scope of the pedagogy to connect educational practices to democratic public life and societal and cultural politics (Giroux 2011); they also emphasize the intersections of educational experiences with race, class, and gender to underscore the importance of centering the learning experiences of marginalized communities and celebrating multiple ways of knowing (bell hooks 1994). Applied to increasingly technology-saturated educational pathways, critical digital pedagogy is positioned as a liberatory praxis to challenge our teaching with and thinking about technology, specifically its role and place when mediating human connections and communication (Stommel et al. 2020). For technology-supported instruction, including online learning, Stommel (2014) posits that the “web is asking us to reimagine how we think about space, how and where we engage, and upon which platforms the bulk of our learning happens” (para. 12). Further, critical digital pedagogy acknowledges that learning is political rather than neutral and urges educators to be critical of how technological advances are used to control and promote political discourse. Engaging a critical pedagogy or critical digital pedagogy lens to online course design and facilitation might look like the following examples:

- As you (re)design and teach your online course, consider making an analysis of your teaching practices as well as digital technologies that support interactions, communication, and learning. Center learning in the design, and think about the reciprocal relationships it has with technologies—how learning is reframed with and through technology, and how technology affords democratic participation in the classroom and supports human connections across age, race, culture, gender, ability, and geography. For instance, a class discussion can be expanded to the social sphere by way of social media posts where students engage with a community of practitioners and scholars.

- When a predesigned course has technologies already integrated, consider inviting students to experiment and contribute to the class with their own discoveries and reflections on technology and how it affects and shapes their experience of learning.

Second, culturally responsive pedagogy aims to recognize and celebrate students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences. An individual’s cultural and racial backgrounds play a role in how they are perceived in educational environments. Building on extensive research on the connection between culture and education, Gay (2018) argues that culture shapes the teaching and learning process because, whether we are conscious of it or not, culture influences how we perceive the world, communicate with others, think, and behave, and these influences may be in agreement or disagreement in the classroom when instructors and students interact. (We look more deeply at specific implications for how cultural difference shows up in the online classroom in chap. 2.)

Culturally responsive approaches to course design help center cultural understanding in instructional practices to “recognize students’ cultural displays of learning and meaning making and respond positively and constructively with teaching moves that use cultural knowledge as a scaffold to connect what the student knows to new concepts and content in order to promote effective information processing” (Hammond 2015, 15). An instructor’s own perspectives can shape the expectations of their students, and these attitudes may be communicated through learning materials selection and course design. Students can maintain their cultural integrity when they are encouraged to do so within and during their studies, and they can be empowered to challenge systems of inequity in their lives (Ladson-Billings 2021). Activities that provide immediate application to practical situations or offer connection to students’ communities and backgrounds can be more relevant and impactful, and they can allow students to not only acquire the knowledge and skills they are expected to learn but also help them see the value and meaning beyond the grade. Consider the following examples as you reflect on your course:

- (Re)designing a culturally responsive assignment in a soil science class might ask students to analyze and report back to the class on soil composition in their own backyard or a community space.

- If you cannot adjust your course design, assess the expert voices represented in the course and its approach to assessments. A limited view of what counts as scholarly knowledge may be “inadvertently supported through bias in testing and textbooks” (Moule 2012, 179), such as if an instructor uses course resources written only by white male authors or relies entirely on timed quizzes and exams for learning assessment. You could contribute profiles or examples of more diverse voices in discussions, course announcements, and the like.

Lastly, we want to expand the notion of critical pedagogies to include additional theoretical frameworks and approaches that challenge traditional teaching and learning where the authoritative figure in the course—the instructor—possesses all the knowledge to be imparted to students and exercises control over student learning in terms of who learns, what needs to be learned, and how it is learned. Antiracist pedagogy can help educators identify how educational practices and policies may perpetuate racial inequities in the classroom, thereby undermining student success. This pedagogy is rooted in the works of Kimberlé Crenshaw, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Ibram X. Kendi, and bell hooks, whose contributions seek to promote reflection and action to address ongoing racial disparities and policies in educational contexts while also affirming and centering students’ identities. It involves recognizing that systemic racial inequities exist because “failing to acknowledge racism not only erases histories, cultures, and identities, but also ignores ongoing differential treatment based on race” (Simmons 2019). An antiracist approach gives instructors (and their students) the tools and resources to enact changes both within their individual contexts (e.g., the classroom) and toward a more just society. For instructors, adopting antiracist pedagogy would mean engaging in critical self-reflection of their social group memberships as well as an examination of the systems, structures, and practices that disadvantage people based on their race. This process involves a continuous self-discovery of their identity, social positions, and educational structures oriented toward understanding and addressing educational inequities.

Critical self-reflection can help instructors become more aware of how their identities and socialization can impact both teaching and learning (we discuss socialization further in chap. 3, in the context of instructor self-introductions). By engaging in the process of critical self-reflection of their social group memberships, instructors will become more aware of how their identities, lived experiences, and scholarly work influence their teaching practices and impact their interactions with students. Self-reflection can enable a deeper analysis of the power structures within and outside the classroom, leading to a recognition that instructors as well as students are on a learning journey. But admitting that instructors are themselves on a learning journey can bring up feelings of vulnerability, even if it is ultimately empowering (Kishimoto 2018). In fact, self-reflection allows instructors to recognize that they can also learn from students, and in doing so, they can disrupt the traditional power dynamics that position instructors as the elite knowledge-bearers (Kishimoto 2018) while giving students voice to engage in mutual, reciprocal learning.

Another key tenet of antiracist pedagogy is challenging Western-centric perspectives in course content. This work requires examining the gaps between privilege and belonging (who is represented in the course and who makes those decisions), acknowledging and reducing race-related biases (how an instructor’s implicit biases can affect interactions with diverse students and the academic expectations the instructor has for them), and mitigating stereotype threat (how a specific teaching approach can empower students) (Killpack and Melón 2017). It might prompt an instructor to (re)redesign a course with an explicit representation and centering of diverse (especially Black, Indigenous, or people of color, known as BIPOC) individuals’ contributions in the curriculum. It can also guide an instructor (and students) to analyze the influential factors (e.g., political, economic, historical) that shape knowledge production in the academic disciplines and its implications in perpetuating inequities (Kishimoto 2018).

As antiracist pedagogy is a process more than a fixed, static goal, it requires a cycle of self-reflection, learning, and action. It is ultimately concerned with the how of teaching, employing instructor self-reflection as a key component (Kishimoto 2018); decentering themselves in the classroom as a first step in implementing this approach. Consider the following examples:

- Create a matrix of sources and materials that students will read/watch each week. Identify the disciplinary areas where students can integrate experiences, contributions, and representation from BIPOC scholars, researchers, and practitioners that provide historical, political, economic foundations for how the disciplinary knowledge, research, and theories became legitimized. Consider creating a self-reflection assignment for students with guided questions about what counts as legitimate knowledge in the discipline, the role of the discipline in dominant ideologies, whose voices are excluded, and so on.

- When faced with the challenge of teaching a course without the opportunity to make changes to it, antiracist pedagogy can still be implemented. Consider challenging students’ thinking when providing feedback or participating in discussions by asking them what alternative ways of knowing or knowledge are excluded, for example. You can also situate yourself and students within the educational system and discipline to analyze the social positions you all hold and how they shape your viewpoints of the topics in the class.

Teaching the Adult Learner

The online student population is largely composed of nontraditional students. A nontraditional student is an adult learner (age 25-65) who has different learning needs, motivations, and experiences than a younger college student (age 18-25), and therefore different approaches to course design may be required.

First, andragogy, the central theory of adult learning, underscores critical principles that guide the design of educational plans (Knowles 1990; Knowles et al. 2005). Key to the theory of andragogy are adult learners and their motivations to learn. Knowles (1990) posits that adult learners have the following characteristics:

- Self-concept: Adult learners develop a sense of ownership of their learning and have intrinsic motivation, leading them to choose when and how they prefer to learn.

- Experience: Adult learners bring to the learning process a wealth of knowledge as well as work and life experiences, leading them to become rich resources of and for learning. They expect the course content to help them add knowledge and skills.

- Relevance and applicability: Adult learners feel more motivated when they see the relevance of content and activities to their life and experiences, and have practical applications beyond the classroom in various contexts.

- Orientation to learning: Adult learners have goals in mind for undertaking academic studies, leading them to seek opportunities to solve problems for personal or professional goal fulfillment.

- Collaboration and respect: Adult learners seek to connect with others who see them as peers and respect their identities, and engage in thinking critically about ideas and understanding the differences between people.

These principles suggest that adult learners seek to be actively engaged in course activities and apply what they learn in relevant and meaningful ways to their context, including life and work experiences. Related to inclusive teaching and design, these principles offer a foundational framework to create online learning environments that recognize and engage the diversity of learners’ backgrounds, experiences, needs, and motivations. For example, these principles can help to identify areas in the course where student choice can be incorporated (e.g., choose-your-own-adventure-style assignments); to design real-world application activities that speak to the personal or professional interests and needs of students; to encourage mutual and peer learning with an openness and tolerance for multiple perspectives; to provide actionable feedback; and to promote deeper learning. Design and facilitation choices built upon andragogical principles are not set in stone. Knowles et al. (2005) posit that these principles are actually “a system of elements that can be adopted or adapted in whole or in part. It is not an ideology that must be applied totally and without modifications” (146). In other words, these principles are flexible and may apply in different ways depending on context. For example, adult students may on occasion lack confidence and self-direction in navigating the online learning environment, which makes sense for learners who may be reentering academia after time away from school. Consider, too, how this framework does not fully address the needs of adult students from marginalized communities who may have less familiarity with the norms and processes of academia and learning online. In response to the variability and diversity we may see in the adult learner population, direction and support are additional dimensions in adult learning that should be considered for online course design and facilitation.

Consider adopting an inclusive approach that leans into the core principles of andragogy while also building in additional and flexible support for students who may need more from their instructor to be successful. For example:

- In (re)designing a course, consider the audience and how they may be welcomed or put off by design choices. An adult business student with extensive work experience might be put off by a writing assignment and peer review activity that have students compose a resumé as practice for applying for their first full-time job. Encourage students to bring their goals and their experience to the course in meaningful ways (e.g., a resumé exercise that helps to clarify current goals at any stage of a student’s career); doing so will better welcome the mid-career adult learner as well as a first-time, full-time, major-undecided undergraduate student who is 18 years old. Both students could learn from each other in the peer review stage, so lean into the benefits of wide-ranging student experiences. Additional supports could be shared for students who were in fact writing their first resumé or who had not written one in a long time, such as web-based guides or links to writing support resources available through the institution.

- If you cannot change the design of the course, a facilitation intervention could be to call attention to the fact that the class will benefit from the wide array of expertise and work experience that peers bring to the activity, and to share additional resources for resumé-writing.

Second, transformative learning theory promotes autonomous learning by engaging learners in critical reflection of the assumptions they have about the world around them. Mezirow (1997) posits that adults have acquired a body of experiences—or frames of reference—that constitute the structures of assumptions through which individuals interpret and make sense of their experiences. These frames of reference include two related dimensions: habits of mind—“broad, abstract, orienting, habitual ways of thinking, feeling, and acting” (5)—and points of view—“complex of feelings, beliefs, judgments, and attitudes” (6). Habits of mind are longer-lasting and may be influenced by cultural, social, political, economic assumptions; points of view are articulated from these habits and shape particular interpretations. An example habit of mind is the belief that success comes only through an individual’s hard work. The resulting point of view is the set of beliefs, feelings, judgments that lead to thinking that some people just do not work hard enough and therefore are not successful. Overlooked in this interpretation are other factors that can impact how that individual is capable of succeeding, such as availability of resources and support systems, experience with significant challenges, and so forth.

When an individual engages in critical reflection of their assumptions, or in other words challenges their own frames of reference, they transform their personal life. In the reflection process, individuals engage in discourse that encompasses critical thinking to help them challenge assumptions and biases. Mezirow (1997) argues that discourse is “a dialogue devoted to assessing reasons presented in support of competing interpretations, by critically examining evidence, arguments, and alternative points of view” (6). In addition, to become “critically reflective of one’s own assumptions and to engage effectively in discourses to validate one’s beliefs through the experience of others who share universal values,” an individual must develop autonomy (Mezirow 1997, 9). Consequently, for adult learners, transformational learning goes beyond knowledge acquisition; it involves developing critical thinking skills to examine personal and others’ assumptions, recognizing existing frames of reference, considering alternative viewpoints, becoming more effective in collaborative problem-solving, and adapting to change.

In the online classroom, students can engage in activities that allow them to see and experience the world beyond their sociocultural, political, economic, and educational contexts. Instructors can help students develop autonomous critical thinking skills, collaborate with others, debunk their own assumptions, and solve problems from multiple viewpoints—approaches that can make the learning environment truly inclusive and supportive of the diversity that students bring to it. Critical reflection tasks may or not be unique assignments; these can be connected to other components of the course. What is of utmost importance is scaffolding to guide students on the path to critical analysis (Woodward and Veal 2022). As you review your course or plan out its design, consider these possibilities:

- Students can be encouraged to share personal experiences related to the content in a discussion or assignment activity and to challenge the ideas of others (rather than the people expressing them). Encouragement should be supportive, assuring students they will not be judged for voicing their opinions. Clear and specific guidelines and scaffolding can prepare students to interact with others in professional environments where collaboration with diverse colleagues is not only expected but also encouraged and valued (Hunt et al. 2015).

- When you facilitate a course, you have the choice to provide feedback, scaffold discussions, and communicate with students directly (e.g., office hours, announcements), providing them with additional guiding questions or strategies they can apply for critical self-reflection, assisting with deeper analysis of their own experiences and perspectives, and emphasizing the importance to listening to others’ perspectives.

Next, self-determination theory (SDT) centers around the satisfaction of learners’ psychological needs. SDT is interested in how to create optimal experiences for students where their psychological needs are supported while promoting intrinsic motivation (Ryan and Deci 2017, 2020). Ryan and Deci (2017, 2020) posit that the deprivation or satisfaction of these needs can impact an individual’s motivation and well-being beyond their goals and values, including the following:

- Autonomy: Being in control of one’s actions and ability to make decisions based on personal interests or external motivations (rewards or punishments).

- Competence: Achieving outcomes and succeeding under well-supported environments, with optimal challenges and opportunities for growth.

- Relatedness: Feeling connected and experiencing a sense of belonging supported through respect and care.

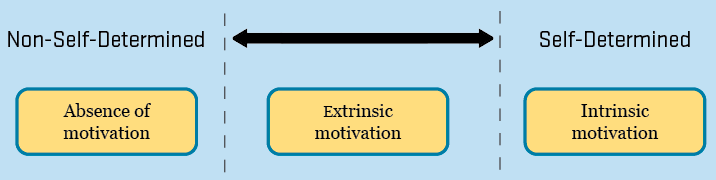

Many learning situations—in higher education and elsewhere—have not yet accounted for this way of thinking about learning progress and efficacy, nor for the importance of instructional faculty adopting a “need-supportive style” (Vermote et al. 2020, 271). Students tend not to be granted autonomy, and they are often framed in deficit language for their lack of competence that needs to be remedied with more practice or more effort. Relatedness is sometimes underscored in theories related to constructivism, yet the default approach to learning is often individual. Students may work with partners or in groups, but accountability for learning progress most often reverts to the individual and the individual grade that they achieve. In addition, in most higher education systems, students do not have much choice in their coursework (outside of designated electives) and much participation in curriculum reform, leading to limited opportunities to expand knowledge and exercise independent learning and autonomy. There are ways to work within these constraints to design learning that ultimately helps to promote student autonomy, competence, and sense of relatedness, however. The SDT framework poses two types of motivation—as a continuum—that help to expose what these better, more inclusive design choices might look like (fig. 1.1).

The first, more common type of motivation in education is extrinsic motivation, which relates to the instrumental value that completing an activity or engaging in certain behaviors has on an individual (Ryan and Deci 2020). In SDT, extrinsic motivation can vary in its degree of autonomy. For example, a student may be asked to submit a summary of their teamwork activities twice during the term. Even though these summaries are not graded, failing to submit them results in a deduction of points from their overall course grade. This activity involves punishment (deducted points), lack of autonomy (no student choice), and compliance (external control).

The second, more effective type of motivation in educational contexts is intrinsic motivation, which stems from the inherent predisposition and interests that an individual has to do an activity and therefore allows them to grow in their knowledge and skills. When an individual student feels intrinsic motivation, they are “moved to act for the fun or challenge entailed rather than because of external prods, pressures, or rewards” (Ryan and Deci 2020, 50). When this natural volitional engagement arises, the resulting sense of engagement and purpose connects the individual and the activity. Also, challenges and performance feedback are related to competence and therefore associated with the complexity of activities, rewards, and positive feedback that can enhance intrinsic motivation.

That these types of motivation are posited as a spectrum is key. Intrinsic motivation is unique to an individual, and not every student will find the course activities intrinsically motivating. Second, the social environment in the course can promote intrinsic motivation or pose barriers to it. Thoughtful design choices like discussing real-world cases and implementing problem-based learning activities can help to increase the likelihood that students will feel some intrinsic motivation, but that outcome is not guaranteed given the variability and diversity of online students.

Additionally, intrinsic motivation can be affected by various other factors, especially the social environment of the course. Think about how dynamics between students or between students and their mentors (say, at an internship site) could impact a sense of autonomy and competence that underpin intrinsic motivation. A student who has identified with the value of an activity might lose that sense of value under a controlling mentor and move “‘backward’ into an external regulatory mode” (Ryan and Deci 2000, 63). That students can move toward or away from intrinsic motivation also highlights that there is no logical or developmental sequence, but instead a fluid spectrum where movement is possible in either direction. In addition, grading is an important element in SDT, as it influences students’ motivation; examining the grading purpose and approach, and perhaps opting for alternative evaluation methods, is another design strategy to support students’ sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Naxer 2020). Considering and perhaps implementing these SDT-inspired approaches to online course design can help us unveil our unintentional choices (e.g., our implicit biases, unawareness of cultural constructs, and more) that promote or pose barriers to meeting students’ psychological needs and addressing motivational challenges.

Opting for design choices that promote students’ intrinsic motivation can help create inclusive learning environments where students can connect with their own interests, learning goals, and tasks, and feel empowered to take a more active part in their learning process rather than submit to the control of the instructor. A few (re)design and facilitation strategies that align with SDT include the following.

- Autonomy: Give students a sense of ownership and control by providing them with alternatives for completing assignments. For example, students could choose between writing a report, creating an infographic, or recording a pitch, allowing them to engage with a medium they prefer.

- Competence: Allow students to build upon their strengths and improve in certain areas through scaffolded assignments where they engage in multiple feedback cycles, and give and receive constructive feedback. Ask them to reflect on and describe their own progress; offer feedback by highlighting strengths and actions they can take to address areas of improvement.

- Relatedness: Give students the opportunity to feel they are contributing to and learning in community by creating group projects where each member of the team has a role and is accountable to the team project success.

In an industrial engineering class influenced by all three components of SDT, students could discuss the implications of food recalls, beginning with a virtual tour of a fruit packing plant that allows them to develop a better understanding of the industry, its technology, and processes. Students could then share in a discussion board their impressions and observations of the plant, and propose a project they would like to work on based on their insights of the tour. The project could be a research paper, video presentation, infographic, or fact sheet that students share with their peers. In this example, students might feel more intrinsically motivated by combining a real-world problem with the flexibility to choose a project and format that best supports their needs and interests as a unique group.

Supporting Learning Differences and Processes

Learners are unique, and designing to meet their learning preferences can support their success. Two of the most prominent frameworks for course design in all modalities are known as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (CAST 2024) and Universal Design of Instruction (UDI) (Burgstahler 2025). Sometimes oversimplified as lenses through which to improve digital accessibility for learners with disabilities—so that students who experience physical, cognitive, and other types of disabilities can have an equivalent course experience as students who do not —UDL and UDI are broad frameworks that intend to proactively design for learner variability and build in elements of flexibility and choice. We would like to underscore the importance of considering UDL and UDI frameworks in all stages of the course development process, rather than as a fix that addresses a student’s request for accommodations.

UDL and UDI are intrinsically tied to the disability rights movement and a series of US laws intended to guarantee equal access to students with disabilities, including in higher education (McAlvage and Rice 2018). Online learning environments pose a unique set of considerations related to disabilities because technology can help students to overcome barriers, but it can also impose additional barriers. Educators may be ethically committed to serve diverse students through application of UDL and UDI principles, but there is also a compliance component: at the time of writing, public higher education institutions must comply with revised Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Title II web accessibility standards, which include course content delivered through a learning management system (LMS), beginning in 2026 (US Department of Justice 2024).

UDL and UDI aim to approach learning design with more than just student ability in mind, while still calling out some of the primary barriers that students who experience disabilities may encounter in learning environments—including online courses. UDL involves addressing students’ barriers to maximize their learning through universal instructional practices that meet students’ unique needs. Three UDL principles can reduce or eliminate barriers for engaging in various parts of the learning process: multiple means of representation, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of engagement (CAST 2025).

UDI embraces UDL principles and addresses specific aspects related to technology access and online environments, including the technological tools, functions of the LMS, and instructional methods (e.g., lecture videos and text-based materials) (Burgstahler 2021). One of the most common and impactful barriers in an online classroom is the lack of accessible materials—videos without captions, images without alternative text, PDFs that are not scanned with optical character recognition (OCR) software to enable applications to read it aloud, and the like. The UDI framework challenges us to view the accessibility of course materials and technologies as a paradigm shift for “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” ( Center for Universal Design, 1997). This means that we should consider a wide range of student characteristics during both course design and facilitation to “ensure access to and inclusion of students who live in different time zones, have a variety of busy schedules, and have a wide range of interests and abilities to see, hear, speak, attend to tasks, organize diverse concepts, use technology, read/speak English, etc.” (Burgstahler 2021, 6). Take learners whose individual differences (such as impaired vision, hard of hearing, dyslexia, etc.) require the use of assistive technologies such as screen readers, text-to-speech applications, and magnification tools. These learners must be able to access all learning materials, activities, and technology features just as those students who do not require such assistive technologies. Additionally, you may have older students who are more likely to benefit from materials made proactively accessible, like larger font in PowerPoint slides or captions available on screen when a voice is difficult to hear. Most learners, regardless of age or ability, benefit from thoughtful sequencing and structure, which in an online course often means presenting modules with an ordered sequence of materials, activities, and tasks rather than a jumble of items for students to sort through (Fink 2013; Artze-Vega et al. 2023).

Assessment methods should also be reexamined through the lenses of UDL and UDI. Traditional assessment methods (exams, quizzes) often fail to capture students’ abilities to demonstrate the knowledge and skills they have acquired throughout their studies. These traditional forms of assessment assume all students learn the same way, and that there is one type of knowledge that can be demonstrated in one way and through one language (Elkhoury 2023). Assessments that give students a choice, engage them in real-life scenarios, or require them to apply what they have learned within their own context can empower students to own their learning process and demonstrate their work through practical, real-world applications (Palloff and Pratt 2013). Incorporating a variety of assessment methods will support students’ learning preferences and promote active learning (Martin and Bolliger 2018) as well as increase their motivation (Wlodkowski and Ginsberg 2017). Including a variety of assessment methods allows instructors to recognize and value students’ cultural heritage and perspectives, provide actionable items for improvement, offer encouragement to build academic capacities, and promote student self-reflection and active participation in the feedback process. All these mechanisms are effective in building a trusting relationship with students. Students can be more receptive to honest and constructive feedback when there is a climate of respect for cultural diversity (Ladson-Billings 2021).

In an online class, there are numerous options for authentic and meaningful assessments. Students could create an infographic or fact sheet to introduce new concepts or explain complex topics, then seek peer feedback to improve it for a final presentation. Alternatively, students could choose their own output format (e.g., visual representation, paper, video) that meets the expectations and lesson outcomes. In designing assessments, instructors can consider Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Outcomes and examine the course’s current assessments to determine where additional supports are appropriate for students; revisit the language used in assessment description and requirements to ensure that it is clear and free of jargon; include a variety of expert voices, experiences, and people to help students see themselves represented in the content of the assessment materials; and follow up with feedback that is actionable and relatable.

UDL and UDI call us to think broadly about student needs and design proactively to meet those needs with accessible content and learning paths; relatedly, strong course design should also consider how students process information, and specifically the limits of that processing. Cognitive load theory helps to guide instructional design choices related to intrinsic load (the inherent challenge of processing any information), extraneous load (the way in which information is presented, including how easy or difficult it is to process), and germane load (the effort needed to organize new information into existing schemas) (Sweller et al. 2011, 57-58). The combination of intrinsic and extraneous load “determine[s] the total cognitive load imposed by material that needs to be learned” (Sweller et al. 2011, 58). When designing an online course, instructors (and instructional designers) must carefully assess the cognitive load of various pieces of a course and whether any unnecessary cognitive load is being created. In doing so, the goal is to maximize working memory resources so that students can ultimately learn the material. Effective visual design in course pages or effective labeling of complex images, for example, could decrease extraneous load. Additionally, breaking complex tasks into subparts is a good strategy for helping students focus on content and processes that are germane to learning. The key is to not overwhelm learners and to help them focus on what is most important. Extraneous load can differ by student; research has shown that neurodiverse learners may experience extraneous load in online courses that are not well designed (Le Cunff et al. 2024, 516). Consider how adult learners who are time limited may also be more successful in a course where navigation, structure, and organization are as clear as possible. Sometimes simple design choices are the most effective to support student learning.

Summary

The learning theories and design frameworks presented in this chapter are not intended to provide an exhaustive list of inclusive design ideas, but rather key principles for providing support and inspiration for inclusive teaching that takes both design and facilitation into consideration. There are many connections between and among these theoretical frameworks and design approaches, and applications of inclusive design often draw on more than one approach. To help make the breadth of these theories more concrete, table 1.1 offers a summary of considerations in designing and facilitating an online course that fosters the academic success of all students.

| Considerations for Design and Facilitation | Suggested Design Approaches | Theoretical Frameworks and Instructional Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Support students’ needs, interests, and diversity | Create activities that build upon students’ previous knowledge, connecting them to their cultures and communities.

Promote team work by providing guidelines for collaborations. Encourage students to set goals and self-evaluate their progress. Create activities for application to the real world. |

Sociocultural theory

Community of Inquiry framework Andragogy Self-determination theory Varied assessment methods Culturally responsive pedagogies |

| Promote curiosity and discovery | Encourage students to be inquisitive and to challenge assumptions and traditional systems.

Encourage students to suggest resources for the class. |

Socioconstructivism

Community of Inquiry framework Transformative learning Culturally responsive pedagogies Critical pedagogy Antiracist pedagogy |

| Promote mutual respect, trust, and empathy | Create activities for individual and team reflection.

Encourage students to view topics from different perspectives. Communicate and interact with students regularly. Recognize students’ contributions to the class. Offer student hours. |

Sociocultural theory

Community of Inquiry framework Transformative learning Andragogy Self-determination theory Culturally responsive pedagogies Antiracist pedagogy |

| Provide relatable content and contexts | Include content from diverse sources and perspectives.

Balance the materials to reflect a wide range of voices and experiences. |

Sociocultural theory

Connectivism Culturally responsive pedagogies Critical pedagogy Antiracist pedagogy |

| Include scaffolding | Provide actionable feedback.

Communicate expectations clearly. Offer opportunities for resubmission of assignments based on feedback. |

Socioconstructivism

Community of Inquiry framework Andragogy Critical pedagogy |

| Offer choice and autonomy | Allow students to choose topics and formats to demonstrate their learning.

Create student-led activities. |

Andragogy

Self-determination theory UDL and UDI |

| Proactively address learning needs and preferences | Provide content and tasks that are relatable to the age and experience of students.

Offer choices of tools and outputs to motivate students and support technology preferences. Ensure that all multimedia (videos, audios) is captioned. Ensure text is readable (word choice, length of sentences, font size and type, headings, searchable PDFs). Ensure all graphs and images have alt text (descriptions that convey the same meaning as the image for people who do not see it) and have color contrast at a minimum of ratio 7:1. |

Andragogy

Self-determination theory Varied assessment methods UDL and UDI |

Reflection and Action

In this chapter, we discussed the overlap between design and facilitation choices through the lens of selected learning theories and design frameworks that guide the creation of more inclusive learning environments. We underscored the complexity of the learning process and how a single, unified theory may be insufficient to account for the learning and support needs of diverse online students. We invite you to consider how you will design or revise a course to implement (or better implement) one or more of these frameworks, or to consider how they were invoked in a predesigned course, with the intention of selecting complementary facilitation strategies as you work through subsequent chapters.

You Might Be Ready to . . .

- Reflect on the strengths and limitations of the theoretical and design approaches, and how these might impact your course design and facilitation choices.

- Begin outlining possible course design or facilitation changes that can be integrated into the course using inclusive design frameworks.

- Purposively identify and apply theoretical insights that support students’ engagement, welcome their lived experiences, and value their diversity.

Questions for Further Consideration

- What insights from the learning theories and design frameworks resonate with your course design or facilitation practices?

- Do you have concerns about deciding how to implement insights from multiple theories and frameworks into your course design?

- What next steps are you considering taking when integrating design and facilitation?

References

Ally, Mohamed. 2008. “Foundations of Educational Theory for Online Learning.” In The Theory and Practice of Online Learning, edited by Terry Anderson, 15-44. Athabasca University.

Artze-Vega, Isis, Flower Darby, Bryan Dewsbury, and Mays Imad. 2023. The Norton Guide to Equity-Minded Teaching. W.W. Norton.

Barab, Sasha A., and Thomas Duffy. 2012. “From Practice Fields to Communities of Practice.” In Theoretical Foundations of Learning Environments, edited by David H. Jonassen and Susan M. Land, 29-65. Routledge.

bell hooks. 1994. Teaching to Transgress. Routledge.

Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. 2021. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610-23. Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. John Wiley & Sons.

Buolamwini, Joy. 2016. “Unmasking Bias.” Medium, December 14, 2016. https://medium.com/mit-media-lab/the-algorithmic-justice-league-3cc4131c5148.

Burgstahler, Sheryl. 2021. “Creating Online Instruction That Is Accessible, Usable, and Inclusive.” Northwest eLearning Journal 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.5399/osu/nwelearn.1.1.5602.

Burgstahler, Sheryl. 2025. “Universal Design of Instruction (UDI): Definition, Principles, Guidelines, and Examples.” Do-It, accessed May 13, 2025. https://www.washington.edu/doit/universal-design-instruction-udi-definition-principles-guidelines-and-examples.

Bruner, Jerome. 1960. The Process of Education. Harvard University Press.

CAST. 2025. “The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 3.0.” Accessed May 13, 2025. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/.

Center for Universal Design. 1997. “The Principles of Universal Design.” College of Design, NC State University, April 1, 1997. https://design.ncsu.edu/research/center-for-universal-design/.

Chen, Michael. 2023. “6 Common AI Model Training Challenges.” Oracle Cloud, December 20. https://www.oracle.com/artificial-intelligence/ai-model-training-challenges/.

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. 2020. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

CoI Framework. n.d. Community of Inquiry, Athabasca University. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://coi.athabascau.ca/coi-model/.

Dello Stritto, Mary Ellen, Greta R. Underhill, and Naomi R. Aguiar. 2024. Online Students’ Perceptions of Generative AI. Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit. https://ecampus.oregonstate.edu/research/wp-content/uploads/Online-Students-Perceptions-of-AI-Report.pdf.

Downes, Stephen. 2022. “Connectivism.” Asian Journal of Distance Education 17 (1). https://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/623.

Elkhoury, E. 2023. “Ten Principles of Alternative Assessment.” In Learning Design Voices, edited by T. Jaffer, S. Govender, and L. Czerniewicz. EdTech Books. https://doi.org/10.59668/279.12260.

Fink, L Dee. 2013. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass.

Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Gaonkar, Bilwaj, Kirstin Cook, and Luke Macyszyn. 2020. “Ethical Issues Arising Due to Bias in Training AI Algorithms in Healthcare and Data Sharing as a Potential Solution.” AI Ethics Journal 1 (1). https://www.aiethicsjournal.org/10-47289-aiej20200916.

Garcia, Heather. 2019. “Accessibility, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and Inclusive Design: What Do They Really Mean?” Ecampus Course Development and Training ( blog), December 16, 2019. https://blogs.oregonstate.edu/inspire/2019/12/16/accessibility-universal-design-for-learning-udl-and-inclusive-design-what-do-they-really-mean/.

Garrison, D. Randy. 2009. “Communities of Inquiry in Online Learning.” In Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, 2nd ed., edited by Patricia L. Rogers et al., 352-55. IGI Global.

Garrison, D. Randy, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer. 1999. “Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education.” Internet and Higher Education 2 (2): 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1096-7516(00)00016-6.

Garrison, D. Randy, Terry Anderson, and Walter Archer. 2001. “Critical Thinking, Cognitive Presence, and Computer Conference in Distance Education.” American Journal of Distance Education 15 (1): 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923640109527071.

Gay, Geneva. 2018. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Teachers College Press.

Giroux, Henry. 2011. On Critical Pedagogy. Continuum International Publishing Group.