5 The Art of Facilitating Inclusive Online Discussions

Introduction

In this chapter, we focus on one of the most impactful ways to demonstrate instructor presence and support student success in an online course: engagement in discussion forums. The instructor has an essential role in developing community in an online course (Major 2022) as well as in guiding student learning, and the discussion forum is a key place where those two responsibilities play out. Most online courses use discussions since they provide opportunities for student–content, student–student, and student–instructor interaction. These forums are also a place where instructors can interact with both individual students and the full class, meaning that there is a lot of potential for how an instructor can productively use that space to do the work of effective and inclusive online teaching.

A common misconception among many instructors, and new instructors in particular, is that online discussions are “student-only” spaces; there may be situations where this is true—say, in a discussion where small groups of students peer review each other’s drafts or discuss their project progress before they go to the instructor for further review and commentary—but this is not the norm. In an on-campus setting, an instructor would not write a discussion prompt on the board, say “discuss,” and leave students alone to initiate and sustain a productive conversation. Students would probably feel abandoned and concerned that they are missing out on what information the subject matter expert would provide by guiding the conversation—and that is essentially how online students can feel when their instructor routinely does not participate in discussion forums. Conversely, a well-facilitated online discussion can feel rich and engaging even though it takes place asynchronously and is often text based. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that student satisfaction in online courses can be connected in part to how much an instructor demonstrates their “presence” in the course, especially in online discussion forums (Ladyshewsky 2013; Gordon 2017).

When we raise such suggestions for deep instructor engagement in discussions with participants in our Inclusive Teaching Online (ITO) workshop, the next question is often “But how will I have time to respond to every student?” Responding individually to each student in every forum is neither practical nor advisable. That approach would create a time burden for online instructors (particularly given the enrollment numbers in many online courses), and it could be perceived as dominating the conversation. There are many roles that instructors can play in online discussions to effectively advance the conversation with students—we will discuss approaches in depth in this chapter—and that lean into quality rather than quantity of contributions. Adept facilitation is a bit of an art and takes practice; this chapter outlines ideas and strategies for how to begin or how to refine your approaches to facilitating online discussions more effectively.

An impediment to effective discussion facilitation that we want to note up front is related to design. Some online courses feature closed-ended prompts, which have only one or a few correct or possible answers, and these prompts are really not a basis for conversation. Such prompts are better suited to individual submission homework-type assignments. In a situation where instructors do not have the ability to alter these prompts, it can be difficult to engage in discussion with students about their answers or to encourage students to respond to each other because, again, the conversation is not going anywhere. If you find these kinds of prompts in your course and are generally not allowed to change the prompt or change the activity type, you might inquire with your supervisor or with colleagues (if you teach a course designed by someone else) about whether an exception could be made to allow more space for conversation. Open-ended prompts, where there are a number of correct or possible answers, are much more suited to conversation and enable the range of discussion facilitation approaches that we share in this chapter.

Facilitating Inclusive Discussions

In the sections below, we address setup considerations as well as facilitation guidance for improving the inclusivity of discussions in an online course.

Establish Communication Norms

An important procedural skill in facilitating any discussion is setting expectations for the group. As we have discussed throughout the book, online students come from such a variety of backgrounds—and some are coming back to school after time away—so it makes sense to establish those expectations early. Many OSU Ecampus instructors provide a set of guidelines for a productive and effective online discussion. Here are the guidelines from our Inclusive Teaching Online workshop as an example:

- The discussion board is your space to interact with your colleagues related to current topics or responses to your colleague’s statements. It is expected that each individual will participate in a mature and respectful fashion.

- Participate actively in the discussions, having completed the readings and thought about the issues.

- Pay close attention to what your colleagues write in their online comments. Ask clarifying questions, when appropriate. These questions are meant to probe and shed new light, not to minimize or devalue comments.

- Think through and reread your comments before you post them.

- Assume the best of others in the class, and expect the best from them.

- Value the diversity of the class. Recognize and value the experiences, abilities, and knowledge each person brings to class.

- Disagree with ideas, but do not make personal attacks. Do not demean or embarrass others.

- Do not make sexist, racist, homophobic, or victim-blaming comments.

- Be open to being challenged or confronted on your ideas or prejudices.

You might share guidelines in your course syllabus, in introductory course information, or in part of the prompt for the first few discussions. Some online instructors ask students to weigh in on them as a way to ensure that students have agency in co-constructing guidelines about how conversations will proceed during the course, usually through a discussion forum activity early in the course, where guidelines are added to and adjusted. (Chap. 6 includes further guidance and an example of building community agreements.)

Debates, Discussions, and Dialogues

In this section, we examine differences in three key types of online conversations and invite you to reflect on which types you use in your online course as a means to help develop more specific prompts for each.

Whether you designed your online course or not, considering (or reconsidering) how you engage with students in discussion forums requires a good understanding of the purpose of each discussion. Just because an activity uses a discussion forum space does not mean it is necessarily a discussion, and in fact well-designed online courses often use forums for many different kinds of cognitive work across a term. One way to unpack how you might facilitate one of these activities is to reflect on whether it is a debate, discussion, or dialogue.

Table 5.1 outlines the differences between these three categories. As you explore it, notice how power dynamics vary substantially for the instructor (facilitator) and for students, and also how content is treated differently in each case.

| Consideration | Debate “Mine is right” |

Discussion “The noisier, the smarter” |

Dialogue “Connectivity for community” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paradigm for communicating across difference | Debate is oppositional; two sides oppose each other and attempt to prove each other wrong. Debate assumes that there is a right answer and that someone has it.

In debate, personal experience is secondary to a forceful opinion. Debate creates a closed-minded attitude, a determination to be right. Individuals are considered to be autonomous and judged on individual intellectual might. |

Discussion tends to contribute to the formation of an abstract notion of community.

In discussion, personal experience and actual content are often seen as separate. Discussions often assume an “equal playing field,” with little or no attention to identity, status, and power. |

Dialogue is collaborative: two or more sides work together toward common understanding.

In dialogue, personal experience is a key avenue for self-awareness and political understanding. In dialogue, exploring identities and differences are key elements in both the process and the content of the exchange. |

| Self-orientation | In debate, one submits their best thinking and defends it against challenge to show that it is right. Debate calls for investing wholeheartedly in one’s beliefs. Debate defends assumptions as truth; defends one’s own positions as the best solution and excludes other solutions; and affirms a participant’s own point of view. | Discussions are often connected with the primary goal of increasing clarity and understanding of the issue with the assumption that we are working in a stable reality. In discussion, individual contributions often center around “rightness” and are valued for it. In discussion, the impact may often be identified and processed individually and outside of the group setting. | In dialogue, one submits their best thinking, knowing that other peoples’ reflections will help improve it rather than destroy it. Dialogue calls for temporarily suspending judgments; dialogue reveals assumptions and biases for reevaluation; and dialogue causes introspection on one’s own position. |

| Other- orientation |

In debate, one listens to the other side in order to find flaws and to counter its arguments. Debate causes critique of the other position.

In debate, one searches for glaring differences as well as for flaws and weaknesses in the other position. |

In discussion, one listens only to be able to insert one’s own perspective. Discussion is often serial monologues.

Discussion tends to encourage individual sharing, sometimes at the expense of listening to and inquiring about others’ perspectives. |

In dialogue, one listens to the other side(s) in order to understand, find meaning, and find points of connection. Dialogue involves a real concern for the other person and seeks not to alienate but yet speak what is true for oneself.

In dialogue, one searches for strengths in the other positions. Dialogue creates an openness to learning from mistakes and biases. |

| Emotions in the process | Debate involves a countering of the other position without focusing on feelings or relationship and often belittles or deprecates the other person. | In discussion, emotional responses may be present but are seldom named and may be unwelcome. Discussion is centered on content, not affect related to content. | In dialogue, emotions help deepen understanding of personal, group, and intergroup relationship issues. Dialogue works to uncover confusion, contradictions, and paradoxes with an aim to deepen understanding. |

| End-state | In debate, winning is the goal. Debate implies a conclusion. | In discussion, the more perspectives voiced, the better. Discussion can be open or close-ended. | Dialogue remains open-ended. In dialogue, finding common ground is the goal. |

Now, consider the following questions as you reflect on forums in your online course:

- Which category (or categories) of conversation best suits your learning outcomes, course content, and discipline?

- Which category (or categories) do your current course “discussion” prompts fall under?

- Are there ways that you might consider reframing your conversations or facilitating them differently based on the characteristics outlined in table 5.1?

One of the advantages to asynchronous online courses is that everyone—or almost everyone—in your class contributes to the conversation since there is rarely (if ever) time in an on-campus class for every student to speak. Yet these online activities tend to put much more emphasis on the student’s initial post rather than their peer responses in much the way that “sharing over listening” is emphasized in the description of discussions in table 5.1. Oftentimes, the instructions for initial posts are much more clearly outlined than those for peer responses, and initial posts are usually weighted more heavily in grading. That (perhaps unintentional) emphasis can diminish the need for students to engage fully and deeply with peers in the remainder of the discussion.

That said, depending on your goals for a particular forum, you might try one or more of the following revisions for its design or facilitation:

- Adjusting the prompt to more explicitly offer meaningful and productive approaches to the peer responses.

- Adjusting the grading of the posts to either favor the peer responses or weight the initial posts and peer responses equally.

- Adjusting your facilitation of a discussion to model the kind of engagement that you want students to have with each other, particularly if you want more of a dialogue-like interaction.

In addition, it is important to be aware of how students’ cultural backgrounds may impact their interactions in an online discussion forum. In chapter 2, we explored individuated and integrated cultural constructs to unpack how aspects of culture and identity influence teaching and learning. These constructs can manifest in online discussions and influence how students see themselves in interacting with others and their instructors, exhibiting different participation behaviors like tending to voice individual ideas or engage in cooperative dialogue and problem-solving. At the same time, students are doing the important work of building their social and professional identities through shared learning and self-knowledge in conversational spaces (Delahunty 2012). You can help students demonstrate or practice demonstrating different conversational behaviors appropriate to the task (and discipline) at hand by being explicit about requirements and norms. Discussion prompts are a great place to employ the Transparent Assessment Design (TAD) framework described in chapter 4.

The Ethics of Mandatory Discussion Participation

In online courses, discussion activities are typically graded to motivate student participation. Some discussions may have lower stakes, such as weekly discussions about content, whereas others may have higher stakes, such as posting a final group project presentation for comment by peers. Even in low-stakes activities such as conversational discussions (of the discussion and dialogue type), instructors may require students to respond to sensitive and controversial topics. You might want to consider whether this blanket requirement for participation is essential to ensuring students meet the learning outcomes for your class, so as to not create unforeseen barriers for students.

In chapter 2, we discussed some of the many and varied experiences and challenges that may impact online students in the classroom. What if one of your students was experiencing stress from housing insecurity at the same time that she was asked to respond to a discussion prompt that triggered a memory of past domestic abuse? This student might carry additional burdens in trying to respond on time, within the parameters of the assignment requirements, and publicly to you and the rest of the class. Heightened pressures and simultaneous recall of trauma could impede her ability to succeed that week in the course, if not beyond.

In an on-campus classroom where there is never enough time to ask for a response from every individual student, it would be perfectly reasonable for this student to attend class, actively listen to others speak to the prompt, and not raise their hand—and this could all count as engaged participation with no penalty for not actively speaking. In online classes that cover potentially sensitive and triggering content, students are not usually presented with an alternative form of participation. Consider: Is this equitable? Instructors might include a course policy where students can reach out about an alternative participation method for discussions that are triggering for them, but even that approach still requires students to disclose (and, to some degree, justify) that they are being triggered.

An alternative approach is to structure discussion grading such that students have to post to a certain number of (graded) discussions across the term, but perhaps not all of them in order to earn full credit in that category. Most learning management systems (LMSs) have the ability to drop a certain number of scores within an assignment category or type. If your course relies heavily on discussions for assessment of course learning outcomes, you could potentially extend this opt-out to initial posts only, not to peer posts, to encourage student engagement in every discussion even if they do not have to share their own initial response.

Discussion Facilitation Roles

The ways in which you facilitate discussions can influence how students participate in those discussions. Too much instructor participation could limit the interaction between students, whereas selective participation with clear structure and rules can promote engagement (An et al. 2009). Research has shown that the number of posts alone has not been found to increase student satisfaction with their online course (Leong 2011); the quality of the contributions is more important than the quantity of instructor posts. That said, there are many ways to effectively facilitate an online discussion, and what you may need to do in any given discussion is fluid—dependent not only on who is in that section of your course but also on the viewpoints being represented and how the conversation unfolds. Because of this dynamic nature, it may be helpful to think about different roles that you can play to productively advance the discussion.

As you review our list of possible discussion roles below, think about which ones you play most often and which ones you may be able to use even if you have not done so already.

- Initial guide: Remember that students may have varying experiences with past online discussions and differing levels of readiness to engage with other students. Students from non-Western cultures may have gone through school looking to the teacher as the prime authority figure and may not have been invited to openly discuss topics with peers; these students may need support in defining their own role and scope of participation in a discussion. Also, any of your students may feel hesitant about engaging in discussions when they (1) do not know others in the class well yet and (2) do not feel like they have expertise on the topic under discussion. Sometimes a sample post from the instructor to help articulate what you are looking for can clarify expectations beyond what you list in the prompt and grading criteria.

- Questioner: We know that humans cannot always see their own blind spots. You can help students to deepen or redirect their thinking by asking follow-up questions about their post or sharing additional information/resources.

- Connector: For large class or discussion groups in particular, discussion threads can become very long between posts and replies. Help students to see where ideas across the discussion are connecting or diverging, which contextualizes and deepens their learning.

- Framer: If your group of students seems to be fairly limited in its range of viewpoints, you might demonstrate support for multiple and other perspectives by posing them in narrative form or linking to additional resources.

- Motivator: Just as you would call out good work in an in-person course, do that in your online course. Students appreciate “public” acknowledgment of their strong efforts and unique contributions; your praise also calls attention to those posts as a model for other students and something that they should be sure to read, even if they are skimming the thread.

- Pilot: You may need to help steer your course’s discussions now and then, either in terms of helping to keep students on track and focused, to manage conflict if it arises, or to help ensure that conversations are headed in a productive direction.

Generally speaking, you may want to lean into roles that students may not often take on. For example, students may engage on a more superficial level about key course topics, so you may need to ask thoughtful follow-up questions to prompt additional or more critical thinking (e.g., play the “devil’s advocate”) to help them examine topics more deeply. If you team teach or have teaching assistants in your course, it is a good idea to explicitly plan out how facilitation in discussions is divided up and what roles are most important to play in particular situations.

Also think about how your role(s) may need to shift over the course of the term. You may need to be an active facilitator early on, when students are just getting to know each other, you, and the course topics. You may be able to adjust your level and type of participation later in the term if discussions are going well.

Finally, while we identified the “motivator” role above as just one of a number of roles you might play in a discussion forum, helpful, constructive feedback to students is a critical part of effective online discussion facilitation; not only does it change the tenor of your presence and of the discussion, but it also does the real teaching work of recognizing or valuing exemplary student work, making important connections, and providing relevant examples such that other students pay attention and learn from them. Resist looking just for faults to correct, and aim to use supportive and encouraging feedback in the same measure that you would use in an on-campus class discussion.

Responding with Equity in Mind

Facilitating discussions effectively also requires taking an equity lens to which students receive instructor replies, questions, and other types of follow-up. One study found that faculty were 94% more likely to respond to a white male student in online discussions than any other student demographic (Baker et al. 2018). Such a finding is of course troubling because it exposes how instructors’ assumptions about student names and implicit biases toward engaging with white male students could affect the learning outcomes and engagement of other students in the class.

Consider using the spreadsheet of student information, such as what we recommended in chapter 4, to keep a tally of who you have replied to on the discussion board and be sure you are responding to different students. You might also track more than just a simple tally to ensure that students are also receiving a mix of positive and constructive replies from you in ways that are visible to their peers. While modeling how to provide constructive criticism or how to express skepticism can be useful facilitation techniques to employ, remember that you can always give private feedback to students when you grade their discussion board posts, too.

The Boundaries of Inclusive Discussion

You may remember from this book’s introduction that one of the reasons that the Inclusive Teaching Online workshop at OSU Ecampus was conceptualized was to help empower instructors to facilitate complex conversations online. Instructors shared that teaching a controversial or sensitive topic online felt challenging compared to in-person teaching, and that the work required to keep discussions productive and to avoid heading in problematic directions was a different set of facilitation skills entirely.

That instructors are concerned about facilitating complex online discussions is not surprising given that hate speech in online spaces is on the rise; in 2023, an estimated 52% of American adults report having been harassed online, and 33% of those adults experienced online harassment within the past 12 months (Center for Technology and Society 2023). The experience of being harassed, witnessing harassment, or even harassing others in other online spaces may have implications for how students engage in online course discussions. Respected publications like The Chronicle of Higher Education have gone so far as to recommend mitigating such issues with controversial topics by holding those discussions in person rather than online (Supiano 2023). But when we need to honor the asynchronous nature of many online course offerings, that approach simply is not possible. We also want to avoid instructors removing complex topics in discussions simply because of the fear that something might go wrong. Rather, we want to provide a framework for instructors to navigate these conversation spaces in asynchronous online classes, while acknowledging that this facilitation can be difficult in any modality but is challenging in unique and acute ways online.

The LARA Method in Online Discussions

LARA,[1] which stands for listen, affirm, respond, and add information, is a technique used in facilitating conversations among participants in a group where controversy may be involved. Below, we address how slight modifications to the original LARA method can provide a useful framework or protocol for responding to student discussion posts, including when a student posts a comment that you or other students may find inflammatory. While the framework articulates four distinct pieces or phases, they are generally meant to all be included in a single response. Example applications of this method will be shared later in the chapter.

Step 1: Listen

LARA in On-Campus Discussions

This method encourages listening to your student until you hear the moral principle that they are speaking from, a feeling, or an experience that you share. You listen until you find a way in which you can open yourself and connect with them.

LARA in Online Discussions

Listening looks different because the conversation is not unfolding in real time. Rather, it is an intentional act of continuing to read (“listen”) until you find that point of connection, and then in your response, demonstrating your listening.

Try to understand what lies at the core of the response: fear, uncertainty, anger, frustration, self-righteousness, entitlement, indignation, disgust, confusion.

- What might a student’s tone tell you?

- What assumptions might their post demonstrate?

- If you know more about this student, that information may help you to answer these questions, but it is still important to listen as you read.

Be sure to listen to what the student is actually saying. In trying to understand what might be behind the comment, we do not want to miss what the student literally said.

Once you have processed the listening step, you will need to demonstrate at the beginning of your response post that you have listened to (and carefully read) the student’s post. (E.g., “Student, I appreciate that you were willing to be vulnerable and write about an example that may have been difficult to share with the group.”)

Step 2: Affirm

LARA in On-Campus Discussions

Wait to respond until you hear the student say something that, on some level, you agree with. You might need to ask clarifying questions to get there.

LARA in Online Discussions

Read for the point of agreement and be prepared to ask clarifying questions, while also paying special attention to the tone in your writing.

This is a step we do not usually think about in a conscious way. Express the connection that you found when you listened, whether it is a feeling, an experience, or a principle/value that you have in common with the other person.

- Affirm whatever you can find in their post that represents what may be, to the student, a reasonable issue or a real fear. If you cannot find anything, there are other ways to affirm, such as drawing out an underlying value that you both share. (E.g., “I can tell by your response here that you feel deeply about your ability to care for your own family.”)

- Ask clarifying questions without patronizing or negative framing, such as “Can you tell me more about ____?”

- The exact words do not matter—the important part is to convey the message that you are not going to be defensive and attack the student, and that you know they have as much integrity as you do.

To be affirming, this step must be genuine rather than “sweet” or “slick” talking. It’s also generally best to use heartfelt, unique language rather than to develop prestructured answers. Note that affirming is not a natural process for many of us, but it gets easier with practice.

Step 3: Respond

LARA in On-Campus Discussions

Avoid starting your response with “but.” Use accurate, factual information about people and events. Respond directly to the concerns or questions raised by the student, which shows that they deserve to be taken seriously. If sharing your opinion on a topic, do not present it as fact or universal truth.

LARA in Online Discussions

Use similar strategies as you would in an on-campus situation, but again pay special attention to the tone in your writing.

We often start with responses to confrontational remarks. Instead, demonstrate listening and affirmation in your post before you respond.

Debaters and politicians (and sometimes the rest of us) often avoid the topic that was raised and talk about a different topic instead in order to stay in control of the situation.

- With LARA, respond to the issue the person raised.

- If you do not know the answers, say so—it is perfectly okay to admit when you do not know something. Refer students to other sources if you know some, or tell them you will find out the answer if that seems appropriate.

Sometimes the student does not really want to hear new information but is simply trying to share their feelings. In those cases, a response might come in a subtler form that acknowledges that the student has been heard.

Also, consider that personal insights and experiences can often be more meaningful and impactful in a way that abstract facts cannot.

Step 4: Add Information

LARA in On-Campus Discussions

Share a resource or a personal story. Think about (and bring up) voices that are missing from the conversation.

LARA in Online Discussions

Use similar strategies as you would in an on-campus situation, but pay special attention to the tone in your writing, and provide links to credible voices and resources.

This step gives you a chance to share any additional, pertinent information.

- It may help the student and/or the rest of the class to consider the issue in a new light or to redirect the discussion in a more positive direction.

- This is a good time to state whatever facts are relevant to the issue the student raised. This may involve correcting any mistaken facts they mentioned; you can offer credible facts at this point because now you have made a personal connection, and so that student is probably more open to hearing your facts than they would have been if you had started with critiques first.

- This is also an opportunity to offer additional resources (articles, organizations, people—preferably as links so they are easily accessible) or to add a personal anecdote.

Additional Considerations with LARA

In the case of an inflammatory student post, remember that your reply post serves both as a response to that individual student and as a signaling mechanism to the rest of the class about how you will handle the situation. Determine how long the post has been available and whether other students have already replied (which might require additional situation management) or whether this post has sat with no peer responses (which might suggest that some students were affected by this post, were unsure about how to respond, or ignored it entirely). The content and tone of your LARA-structured response may need to be adjusted based on these considerations.

If the student post is especially problematic, you may need to pursue further follow-up beyond a LARA-based reply. We will discuss additional actions in more detail below.

Comfort, Risk, and Danger

In the Social Justice Education Initiative (SJEI) workshops at Oregon State University, the program director, Jane Waite, introduces a three-part concept of Comfort, Risk, and Danger Zones, originally based on a protocol from the National School Reform Faculty database. These three categories are useful as a reference for how to navigate rude, inflammatory, and biased posts from students as well as for navigating our own feelings that may arise about those posts.

- Comfort Zone: A place where we feel at ease, with no tension, have a good grip on the topic, like to hear from others about the topic, and know how to navigate occasional rough spots with ease. It is also a place to retreat to from the Danger Zone. For example, one of your Danger Zone aspects may be when people start disagreeing with passion and even disrespect. You might find that when that happens, you retreat into your Comfort aspect of listening and not intervening, or even find a way to divert the conversation to a topic that is in your Comfort Zone.

- Risk Zone: This is the most fertile place for learning. It is where most people are willing to take some risks and not know everything or sometimes nothing at all, but it is where they want to learn and will take the risks necessary to do so. The Risk Zone is where people open up to others with curiosity and interest, and where they will consider options or ideas they have not previously considered.

- Danger Zone: Generally it is not a good idea to work from either your own Danger Zone or anyone else’s. It is an area so full of defenses, fears, red lights, desire for escape, and the like that it is hard to accomplish anything. The best way to work when you find yourself there is to own that it is a Danger Zone and work on some strategies to move into the Risk Zone (either on your own or with colleagues) (Wentworth 2001).

Consider where your own course discussion topics are for you. Are they all in the Safety Zone? Are any in the Risk Zone? Could any cause students to tip into the Danger Zone? Remember, too, that a topic that is comfortable for you to converse about—perhaps because you are an expert and have worked on it for many years—may not be comfortable for your students. Discussions in the Risk Zone, as the definition above notes, are great places to “stretch” participants for learning, but if there is a possibility that a discussion could tip into the Danger Zone for either you or your students, you may want to consider how to mitigate the pressures that come up by adding especially careful directions, referencing policies about classroom communication and particularly attentive facilitation (especially in discussions).

When to Engage Additional Resources

Our adaptation of the LARA method provides a framework for responses to all kinds of student posts, from innocuous to provocative, but it is important to define your boundaries around what is permitted in your classroom discussion and what is not. Identifying this line is a complex balancing act of our notions of freedom of speech and our need to ensure that the dignity, humanity, and worth of everyone in the classroom is acknowledged (even when conversations veer into the Risk Zone). Knowing more about where to draw that line will help you to feel more prepared to facilitate your online discussions.

If a student’s post is pushing the boundaries that you set out in the course, seek a second opinion. As an instructional faculty member, it is an important skill to know when you should no longer handle an issue entirely on your own and when you need to consult with someone else to determine the next step. A trusted colleague in your department may be able to offer a second opinion, and you are also encouraged to contact your supervisor and talk through recommendations for next steps. If you are responding to this student on the discussion forum, using the LARA method to continue to engage that student and ultimately provide redirection or an alternative perspective will help you avoid alienating that individual student from the group, support that student’s progress as a critical thinker, and signal to the other students in the class what a compassionate but firm response looks like in a moment of uncertainty or controversy. Modeling this type of response can be a great learning opportunity for your students, particularly at a time when students do not have good models of civilized, productive discussion in the media. Alternatively, this may be a situation where you might attempt to take a longer conversation with that student out of the discussion board and into email, a phone call, or a web conference.

If a student’s post blatantly violates the discussion and communication norms of your course, engage the resources available to you at your institution. Your supervisor or department chair can be a good first resource. At a minimum, you will need to intervene in the course discussion to deescalate the conversation, but you may also need to take additional action. Your institution may also have a formal process for addressing incidents of bias or discrimination. Depending on your institution’s LMS settings, you also may have the ability to delete the post from the discussion thread if needed, but you will want to screenshot and document the post before you delete it. Consider how to support others in the class who may have seen this post before it was removed, within the discussion board itself, as an announcement, or by checking in with students individually.

Further Considerations for Problematic Student Posts

Sometimes when reading a student post, you may find yourself in the Danger Zone. How do you get yourself back to the Risk Zone before you respond? You might need to step away momentarily, and the asynchronous online classroom affords you that opportunity. As we mentioned above, it is also a good idea to lean on a trusted colleague, your supervisor, or another member of the support staff at your institution to help you determine if the student’s post rises to the level of a bias incident and should be handled through an established institutional process.

When you and other students are not pushed into the Danger Zone but you find yourself in a space of strong disagreement with ideas that a student may be expressing, we would encourage you to reflect critically about how you respond to these students to support open dialogue. Instructors at many academic institutions tend toward ideas coded as being liberal, so students who hold more conservative ideas (especially politically) sometimes report that they feel isolated at their institutions or choose not to speak up in discussions (Binder and Wood 2011; Johnson 2019). In scenarios involving strong disagreement, using the adapted LARA method provides you with a framework for continuing to build a relationship with your students by demonstrating active listening, which will in turn allow you to present alternate perspectives that they can explore in a more open-minded way.

Scenario: How Would You Respond?

Depending on the types and content within the courses that you teach, you may be more or less likely to encounter a severely problematic student discussion post. Instructors whose teaching involves ethical quandaries, topics of social justice, or other sensitive content may need to employ the adapted LARA method with some frequency. Conversely, instructors who teach math or lab science courses may not be discussing tough topics with students and may not need to use the adapted LARA method in discussions often. Note, however, that LARA can be used in all kinds of interactions with students where tension might be heightened—including course concerns or grade disputes—as well as in common contexts like providing feedback on student work.

The adapted LARA method takes practice to apply, and whether you are likely to need it in regular discussion forums with students or not, it can be helpful to work through a scenario so that you better understand how you might use it should you ever need it—also using the tools of assessing danger, risk, and comfort in ethical discussions. Below, we offer a sample student post that would be challenging to respond to and where LARA can help frame a productive reply. This post has been altered to protect student, instructor, and course anonymity but is based on a real example from an online course. The exercise below can be done on your own but is a fantastic springboard for discussion if you have an opportunity to talk it through with colleagues.

Warning: the sample student post below includes strong race- and gender-based assumptions. We have chosen to include this example because it is politically charged and reflects poor reasoning and projections of bias, which are not uncommon elements to encounter in discussion posts as learners begin wrestling with complicated topics. It is also the kind of post that may have an immediate negative impact on other members of the class community, and for that reason we invite instructors to quickly provide a counternarrative and model more nuanced and critical thinking.

The Student Case

You are teaching a course on public health, and one of the modules asks students to consider what role community education programs could play in reducing health disparities related to race or ethnicity. You know from past experience that students sometimes struggle with fluently articulating their thoughts on this topic and pulling in the course resources for that week, so you have the best intentions of checking in on the discussion board each day while students are completing the activity (Monday through Thursday). But Monday and Tuesday that week are booked with meetings, and so you do not actually take a look at the discussion forum posts until Wednesday morning.

The first few student posts are engaging and insightful. Students are contributing helpful examples and teasing out some of the nuances in peer response posts. Then, you see a post in the middle of the thread: it has no student responses, and it was posted on Monday at 10:23 p.m. The post reads as follows:

At the end of the day, the problem of racial minority groups being disproportionately affected by bad health outcomes in this country is based in a lack of education and too many single-parent households. The majority of Black, Latino, and Native American births are to women who are unmarried. The CDC report cited below says that households ran by a single parent are going to have fewer financial resources and therefore will not be able to afford better health resources. People in these lower tiers of socioeconomics are also more likely to drop out of school. Education seems to predict and determine socioeconomic status as well as single-mother status. Those who have not completed basic education are more likely to become teen moms and so they perpetuate the cycle of poverty that keeps people from accessing better healthcare during their lifetime. Healthcare includes sexual health, and children of single mothers are more likely to not get education on STDs, are more likely to get an STD, and are more likely to have less in the way of financial resources to treat that medical condition. Not only that, but children living with mothers who are living with men that are not their biological fathers are 33 times more likely to be abused, which usually leads to psychological trauma as well as bodily harm. A mother who makes the choice to have multiple men around in the house adds to those chances for abuse. This then leads to lasting health concerns for the minority children. The issues of teen pregnancies and single moms must be addressed to ensure full-time enrollment in schools and the other piece that must happen at the same time is encouraging family planning to create stable homes with parents who have more money, and these issues are most significant for minority groups. For this improvement to happen, there needs to be a big cultural shift in family planning for these groups but also just in general. Increasing education is pointless unless the target audience is showing up. To sum up, promoting nuclear families must be the priority before any change or addition to education will have a chance of making a difference.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5333a1.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/minorities.htm

https://cis.org/Camarota/Births-Unmarried-Mothers-Nativity-and-Education

https://www.drphil.com/advice/parenting-in-the-real-world-shocking-statistics/

Consider what information from this post you are taking into account and how you are processing it; consider also what additional context about the student and their work in the course you would want to reflect on if this was really your course and your student. If part of your plan involves responding to the student—on the discussion thread and/or in a private message—this would be a good place to try out the adapted LARA method.

Sample Instructor Responses

Instructors who have completed the Inclusive Teaching Online workshop through OSU Ecampus have worked through this scenario in a small-group discussion. With their permission, we share some of their sample responses below to provide a sense of the breadth of possible responses and how different approaches could be effective. As you read through these responses, consider the different ways these educators are listening, affirming, responding, and adding information.

Raven Chakerian, World Languages

Hi, Student. In reading through your detailed response, I can tell that higher rates of poor health outcomes, especially sexual health outcomes, for minorities is an area you are concerned about. You bring up important points about the overlapping challenges faced especially by African Americans, Latinos and Native Americans.

You state that “there needs to be a big cultural shift in family planning for these groups.” This reminded me of an experience I had in a former job in a federally funded nutrition education program called WIC. The nutrition education program served mostly Latino families. When I was hired, the public health nurses were working to adapt their materials and approach to intervention to be culturally appropriate for the families they served. When they implemented the new curriculum, the program completion rates were much higher, as were the health outcomes of the participants. I wonder if something similar could be done with sexual health education? What about the approach currently being used might be imposing unexpected barriers for participants? How could community health education programs do a better job of providing a safe, inviting and inclusive space?

The CDC article on STDs that you list in your resources states, “Even when health care is readily available to racial and ethnic minority populations, fear and distrust of health care institutions can negatively affect the health care-seeking experience. Social and cultural discrimination, language barriers, provider bias, or the perception that these may exist, likely discourage some people from seeking care. Moreover, the quality of care can differ substantially for minority patients. Broader inequities in social and economic conditions for minority communities are reflected in the profound disparities observed in the incidence of STDs by race and Hispanic ethnicity.”

Can you think of ways of reducing the fear and distrust of health care institutions referred to in the article you read? What about the other barriers mentioned? How might those be reduced?

Thanks for your contributions to this discussion, Student. I look forward to hearing your follow-up thoughts.

Lara Letaw, Computer Science

Hi [Student],

You’ve shared your thoughts openly, and that’s a big part of what makes these discussion spaces valuable.

There is a lot of evidence that supports your claim of more education being positively correlated with better health [REFS]. There is also evidence that associates family instability with negative mental and physical health outcomes, including STIs [REFS]. However, family instability can take on many forms and is prevalent even in nuclear families (the definition of “nuclear family” I’m using is, “a family group consisting of two parents and their children”) [REFS].

At the heart of the matter is that negative *life* circumstances tend to cluster together, and that racial and ethnic minority groups tend to disproportionately experience those negative circumstances (and there are many reasons for this [REFS]). However, if we increase just one factor—education—and leave others the same, we see improvement across many of those circumstances [REFS].

As a note: The fourth link you provided (“Parenting in the Real World”) does not cite any sources. Because of that, we (you, I, your classmates) don’t know where the information came from or whether or not it was correctly interpreted/represented in the article. Because the authors do not provide verifiable evidence for their claims, that also creates a weakness in your own arguments.

Ean H. Ng, Industrial Engineering

[Student],

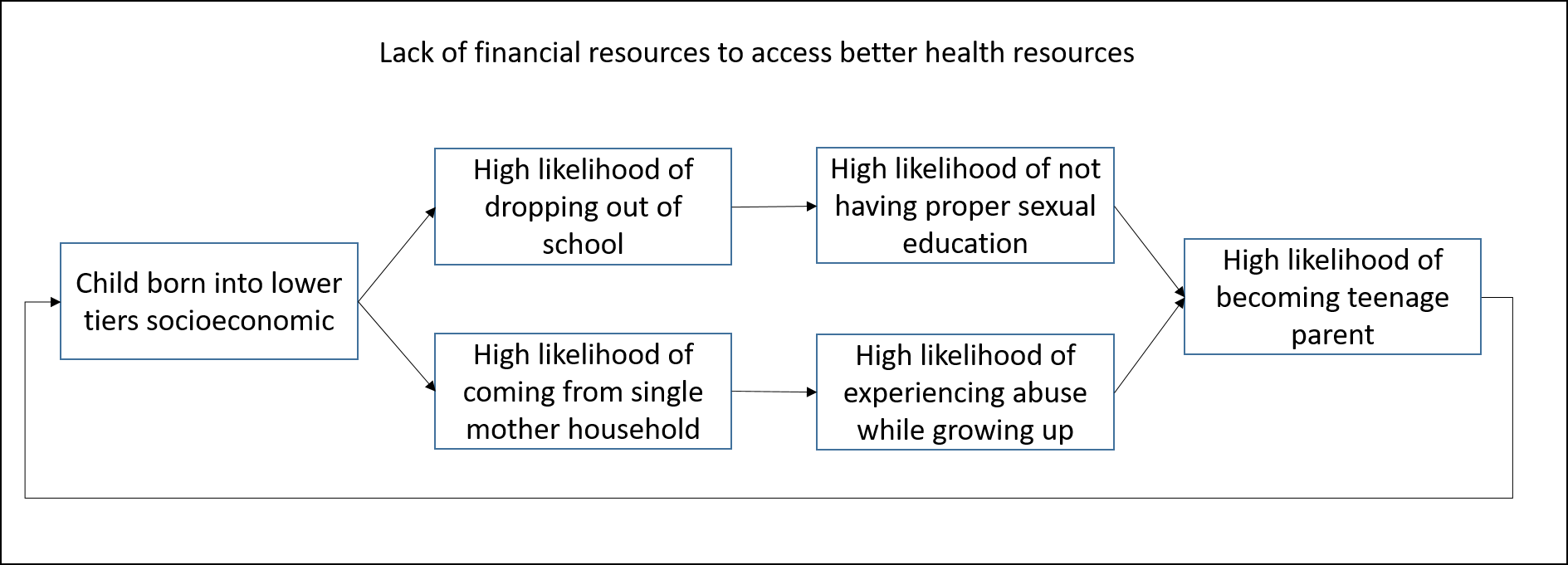

I hear you on the frustration with the ineffectiveness of community education in reducing health disparities related to race or ethnicity. I have created a diagram based on my understanding of your post.

I am glad to see that you notice the vicious cycle that the racial minority groups experience, and how this vicious cycle is perpetuating the cycle of poverty.

Since we are in a public health course and we are discussing community education programs, let’s look at the vicious cycle that you observed, and let’s think about how we can help to break this vicious cycle from a community education standpoint. After all, the goal of public health, as defined by CDC, is the “science of protecting and improving the health of people and their communities,” and this includes all people from all backgrounds.

You have noted that community education, in its current form, is ineffective since the population that needs the education is not showing up. Can you think of another way to deliver the education so that the population that needs it will receive it without having them coming to us?

Looking at the vicious cycle you observed, is there another part of the cycle that we can act on to help break the cycle? For example, what is the feasibility of delivering the education early on in the school curriculum before they drop out?

As for promoting nuclear families, without infringing on individual rights, how should we go about to promote this idea if community education is ineffective?

Anonymous, Environmental Sciences and Ecology

[Student],

I appreciate that you did your best to address the assigned topic, from your perspective, and found sources to support your conclusions. Unfortunately, you have not taken to heart in this assignment the first principle that we must affirm our own and others’ humanity by considering the world from their perspectives and experiences with compassion and open mindedness, not prescriptive judgment.

In the process you also did not address the assigned topic, which was not whether community education programs can help, but how. Though I doubt it was your intent, the argument you made was upsetting and cast judgment upon human experiences, ignoring the realities that we have already discussed in this course of racial and gender disparities due to complex and multigenerational political, social, and cultural dynamics. (Please refer to X, Y, Z from module 123.)

Before I go further, I need you to know that I come into this from a very personal place. Though I am white, and my mother had me later in life, the statistics that you cited here applied to me as a child, and the social pressure to conform to a “nuclear family” was what put my mother and me in harm’s way. It was only when my mother was empowered to support herself, and then in turn worked to support teen mothers who had been written off by society, that my family found hope, health, and stability. We were still poor, but we were no longer trapped. The difference between myself and the children of minority communities is that my whiteness gave me access to opportunities and education, and once I had “arrived,” I was accepted as deserving. People of color are not given that privilege. Community education programs are often the only resource available in communities of color to support mothers like mine and children like myself, for exactly the reasons that you outline in your argument—they are assumed to be undeserving, rather than trapped in a system that will not let them succeed.

In your argument, the actions of individuals are more powerful than the systems they exist within, which, as we have previously discussed, can perpetuate systems of oppression. Your argument implies that the cycle of poverty, abuse, and negative health outcomes is put on the shoulders of women who “chose” not to be in “nuclear” families. There are many problems with this logic, but first I need you to know that population-level statistics cannot be applied to individuals or to individual communities—it is both inappropriate scientifically (as they are correlational) and more importantly effectively erases our personhood. Statistics can be useful, but they are not predictive or prescriptive, and they cannot give us answers to complex human experiences. Let me be clear: The disparities in health outcomes in minoritized communities are not due to the choices of single mothers or the presence or absence of nuclear families. The concept of a nuclear family is a cultural construct and does not apply universally to the human experience; it is also not a guarantee of better health or income [insert stat here]. [Here I would insert various sources and stats about how women’s rights and access to education/economic opportunities improve these outcomes, and stories about women whose lives were improved by the efforts of community outreach groups.]

I regret that your post in this discussion fell short of the course requirements. I expect all of my students to meet our expectations of community dialogue, and to suspend judgment in favor of compassion and inquiry. I am certain that in the future you will continue to meet these expectations, as you have in previous discussions, so we can move forward together.

Reflection and Action

In this chapter, we looked closely at discussion facilitation approaches that engage students individually and as a group while also creating an online classroom environment where a variety of viewpoints and lived experiences are appreciated and brought productively into the conversation. Consider implementing one or more of the suggested action items below in a current or upcoming course; other suggestions may take more time and may be more appropriate for a future course offering. Then, we invite you to continue on to chapter 6, where we discuss strategies and special considerations for instructors teaching online courses that include social justice themes.

You Might Be Ready to . . .

- Evaluate how you frame or facilitate a discussion based on whether it is a discussion, debate, or dialogue and make adjustments to how you guide students toward the kind of interaction you want to see.

- Consider adjusting discussion participation policies in your course to allow students to opt out of one (or a few) discussions during the term with no penalty.

- Employ one or more new discussion facilitation roles.

- Use the adapted LARA method to respond to problematic student posts or any communication with students where there is heightened tension.

Questions for Further Consideration

- Do these strategies and recommendations for effective, inclusive, and equitable discussion facilitation prompt any revisions to your plans for how to engage your online students? For example, do you need to adjust your commitments to various tasks in the course to make more room for discussion participation?

- Which of the instructor examples of LARA responses would you emulate? Why?

- Do you have a plan for how to raise concerns about problematic student work, particularly discussion posts, such as through an established institutional process or with your supervisor? Do you know who at your institution can support you if the content triggers you?

References

An, Heejung, Sunghee Shin, and Keol Lim. 2009. “The Effects of Different Instructor Facilitation Approaches on Students’ Interactions during Asynchronous Online Discussions.” Computers and Education 53 (3): 749-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.04.015.

Baker, Rachel, Thomas Dee, Brent Evans, and June John. 2018. Bias in Online Classes: Evidence from a Field Experiment. Working Paper 18-03. Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://cepa.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/wp18-03-201803.pdf.

Binder, Amy J., and Kate Wood. 2011. “Conservative Critics and College Students: Variations in Discourses of Exclusion.” In Diversity in American Higher Education: Toward a More Comprehensive Approach, edited by Lisa M. Stulberg and Sharon Lawner Weinberg. Routledge.

Center for Technology and Society. 2023. Online Hate and Harassment: The American Experience 2023. Anti-Defamation League. https://www.adl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/2023-12/Online-Hate-and-Harassmen-2023_0_0.pdf.

Delahunty, Janine. 2012. “‘Who Am I?’ Exploring Identity in Online Discussion Forums.” International Journal of Educational Research 53: 407-20.

Gordon, Jessica. 2017. “Creating Social Cues through Self-Disclosures, Stories, and Paralanguage: The Importance of Modeling High Social Presence Behaviors in Online Courses.” In Social Presence in Online Learning: Multiple Perspectives on Practice and Research, edited by Aimee L. Whiteside, Amy Garrett Dikkers, and Karen Swan. Stylus.

Johnson, Steven. 2019. “Conservatives Say Professors’ Politics Ruins College. Students Say It’s More Complicated.” Chronicle of Higher Education, August 20, 2019. https://www.chronicle.com/article/conservatives-say-professors-politics-ruins-college-students-say-its-more-complicated/.

Ladyshewsky, Richard K. 2013. “Instructor Presence in Online Courses and Student Satisfaction.” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 7 (1): 1-23. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2013.070113.

Leong, Peter. 2011. “Role of Social Presence and Cognitive Absorption in Online Learning Environments.” Distance Education 32 (1): 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2011.565495.

Major, Claire. 2022. “Examining the Tie That Binds: The Importance of Community to Student Success in Online Courses.” Journal of Postsecondary Student Success 1 (4): 20-34. https://doi.org/10.33009/fsop_jpss131190.

Supiano, Beckie. 2023. “Teaching: How to Hold Difficult Discussions Online.” Chronicle of Higher Education, November 9, 2023. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2023-11-09.

Wentworth, Marylyn. 2001. Zones of Comfort, Risk and Danger: Constructing Your Zones Map. National School Reform Faculty Database. https://www.nsrfharmony.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/zones_of_comfort_0.pdf.

- Adapted from the handout “LARA Method: Responding to Comments and Questions” from the Oregon State University Office of Institutional Diversity; content derived from B. Tinker’s LARA: Engaging Controversy with a Non-violent, Transformative Response (workshop handout available by request from info@LMFamily.org), 2004. ↵