1 TeachEngineering (TE) Overview

Introduction

This chapter contains an overview of the TeachEngineering (TE) system (www.teachengineering.org). We briefly discuss its origin as an attempt to build a unified digital library from a diverse set of K-12 engineering curricula which had been developed at various US engineering schools. At the time of its inception in 2002, few if any standard solutions for this problem were available and the system was designed and developed from the ground up. It became one of several hundred digital libraries which around 2005 comprised the National Science Digital Library (NSDL) project, funded by the US National Science Foundation (Zia, 2004). Now, quite some time later, TeachEngineering enjoys a user base of about 3.5 million users, has recently been rebuilt on a new architecture and remains as one of fewer than 100 collections in NSDL.

Brief History

In the late 1990s the Division of Graduate Education (DGE) of the US National Science Foundation started its Graduate STEM Fellows in K-12 Education or GK-12 program (NSF-AAAS, 2013). The program meant to bring K-12 Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) teachers and university graduates together in an attempt to develop new and innovative K-12 STEM curriculum. With an annual budget of about $55 million, by 2010 the program had made 299 awards at 182 institutions, provided resources to almost 11,000 K-12 teachers in 5,500 schools and impacted more than 500,000 K-12 students (NSF, 2010). In the process, a treasure trove of innovative STEM curriculum had been developed.

Unfortunately, most of that curriculum sat undetected on ‘Google shelves’ where, through the usual processes of web site entropy and link rot, it quickly became stale and abandoned as its creators, having completed their projects, went their ways. It was, as described by Lima (2011) in relation to information visualization websites, as if “the whole field suffers from memory loss.” To make matters worse, the GK-12 curriculum was not published to any standards and hence, existed in a multitude of layouts and electronic formats, various logical structures and hierarchies, and followed many different kinds of pedagogical approaches. As a consequence, much GK-12 curriculum was difficult to find; was lost in a sea of Google search results; was rarely aligned with K-12 educational standards; was not maintained; and was difficult to compare with and relate to other GK-12 materials.

Foreseeing this process of curricular entropy, a group of engineering faculty and GK-12 grant holders at the University of Colorado, Duke University, Colorado School of Mines, and Worcester Polytechnic University, supplemented by one of us from Oregon State University (Figure 1) decided to apply for an NSDL grant to collect all GK-12 engineering curriculum ―the E in STEM― standardize it, make it searchable, align it with K-12 educational standards, and host it as one of NSDL’s digital libraries. That was in 2002. Now, 16 years later, TeachEngineering is still supported by NSF and a variety of other funders. It has grown to more than 1,500 curricular items contributed by many universities and programs and enjoys a patronage of over 3 million users per year. NSF’s GK-12 program is no longer active but curriculum developed in other NSF programs, such as Research Experiences for Teachers (RET) and Math and Science Partnership (MSP), as well as that of lots of other K-12 curriculum developers continues to find its way to TeachEngineering for two reasons: because NSF encourages its grantees to publish their work in TeachEngineering and because TeachEngineering consolidates good K-12 Engineering curriculum in a single, searchable and easily operable location on the web.

The TeachEngineering Document Collection

A quick look at TeachEngineering curriculum (https://www.teachengineering.org/curriculum/browse) reveals how the library is structured. It consists of a collection of documents, each of which is of one of four types: activity, lesson, curricular unit and sprinkle. Lessons introduce certain topics and provide background information on those topics. Practically all lessons refer to one or more activities which are hands-on exercises that illustrate and practice the concepts introduced in the lesson. When several lessons all address a central theme, they are often —although not necessarily— bundled on a so-called curricular unit. Sprinkles are shortened versions of activities. They are not part of lessons and curricular units and are therefore not part of fully structured learning plans. Instead, they are meant for informal learning settings such as after-school clubs. All sprinkles are in both English and Spanish.

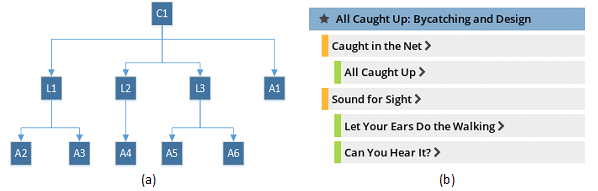

All documents are further classified to belong to one or several of 15 subject areas (Algebra, Chemistry, Computer Science, etc.). For example, the unit Evolutionary Engineering: Simple Machines from Pyramids to Skyscrapers is categorized under the subject areas Geometry, Physical Science, Problem Solving, Reasoning and Proof, and Science and Technology. It has six lessons and seven activities. Lessons and activities do not have to be part of units; they can live ‘on their own,’ and activities can be part of curricular units without being part of a lesson. This hierarchical structure is unidirectional. This means that whereas activities or lessons can live on units, units cannot live on a lesson or an activity. Nor can a lesson live on an activity (Figure 2).

As of January 2020, TeachEngineering has 89 curricular units, 516 lessons and 1059 activities.

Controlled Document Content

In order for TeachEngineering to expose and disseminate K-12 engineering curriculum in a single, unified, standards-aligned, searchable and quality-controlled digital library, a standardized structure had to be imposed on each and every document. For instance, all activities, lessons and curricular units must have a summary section, a section which explains the curriculum’s connection with engineering, a set of keywords, the document’s intended grade level, the time required to execute it, a set of K-12 educational standards to which the curriculum is aligned, etc.

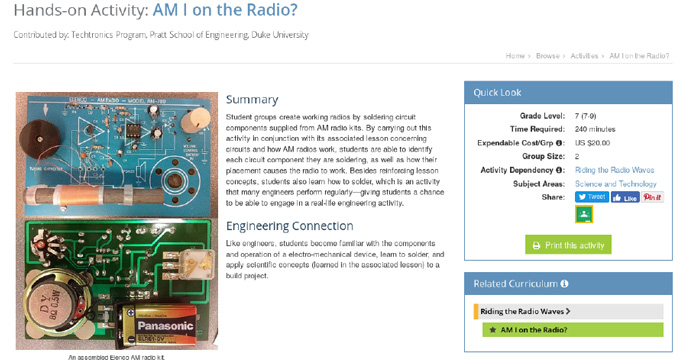

Figure 3 shows part of a TeachEngineering activity as it appears in a user’s Web browser. Note its Summary, Engineering Connection and the data in the Quick Look box.

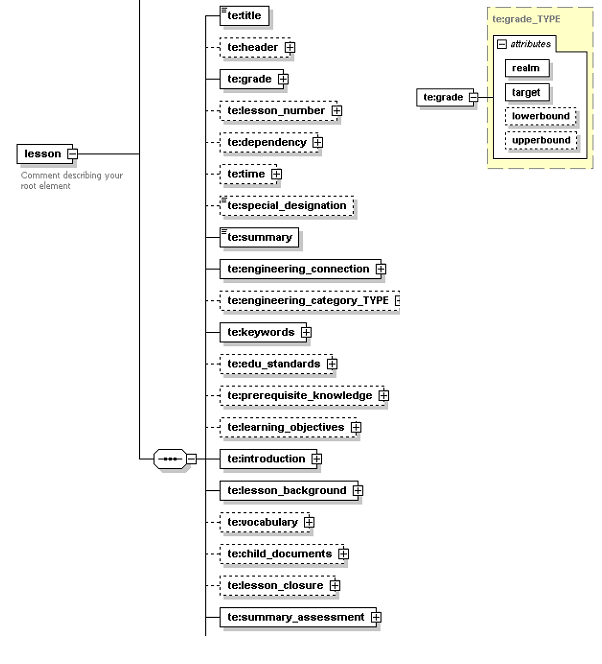

Although the precise list of document components —different for different document types— is not important here, it is important to realize that these components come in two types: mandatory and optional. Figure 4 graphically displays some of the components of a TeachEngineering lesson. Solid-line rectangles indicate mandatory components, while dashed lines indicate optional components. Note that the content specification once again is a hierarchy. For instance, while a lesson must have a grade specification (te:grade), the grade specification itself must have a target with optional upper– and/or lower bounds. When we consider this type of hierarchy as a tree (Figure 4), the leaves of this tree —its terminal nodes— must be of a specific computational data type (not shown in Figure 4). For instance, the target lowerbound and upperbound values must be byte-size integers.

Putting such strict structural and data type constraints on document content accomplishes two things. First, it allows the construction of a collection of documents with a single, unified content structure and a common look-and-feel. Second, and just as important, it allows for automatic, software-based procedures for processing collection content. Examples of these processes are document ingestion and registration —a process known as document accessioning— quality control, document indexing, and metadata generation.

The latter point ―automatic generation of metadata― is important as it is a classic bottleneck in the population of digital document repositories. With metadata, we mean data about a document rather than the document’s content. For example, author names, copyrights and title, or in our case, things such as grade level, keywords, expendable cost, required time, etc. Collections which rely on manually entered metadata often suffer from the classic problem that such data entry is boring, time consuming, is error prone and must be reviewed and possibly redone when a document changes. As a consequence, much of the items in digital libraries have very minimal metadata, which itself reduces their chances of being found in searches and therefore their chances of being used. Being able to automatically generate a lot of good metadata is therefore a good thing. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 cover the various ways in which TE content was and is controlled in TE 1.0 and 2.0.

K-12 Educational Standards

It will come as no surprise that in this age of performance metrics, K-12 education is subject to delivering predefined learning outcomes. These outcomes are known as ‘educational standards’ or ‘standards.’ In the USA the determination and authoring of these standards is the authority of individual states and within the states sometimes of individual districts. Although attempts at harmonizing standards across states ―we refer to the Common Core for Mathematics and English and the Next Generation Science Standards initiatives (Conley, 2014; NRC, 2011)― have met with some success, the USA educational standards landscape remains quite complex and in constant flux. Not only do standards change on a regular basis, but different states have different standards; they completely or partially adopt the harmonization standards or write their own variations of those standards. When they write their own, the standards show great variety in granularity and approach between states (Marshall & Reitsma, 2011; Reitsma & Diekema, 2011; Reitsma et al., 2012). The fact that across the whole USA there are approximately 65,000 K-12 science standards, speaks to the complexity of the USA’s K-12 standards landscape.

Early in development of TE 1.0, our TeachEngineering team decided that we were in no position to continuously track evolving K-12 Science and Engineering standards and that we would prefer acquiring those standards from an external provider. Similarly, since figuring out for all 50 states and for each document which standards are supported by (align with) which document was not one of our core competencies, we hoped to acquire this service elsewhere.

Fortunately, at the time of TE 1.0 development, the Achievement Standard Network (ASN) project was established (Sutton & Golder, 2008) and was, like TeachEngineering, partly funded by NSF’s NSDL project. The ASN project maintains a repository of all K-12 educational standards in the USA, issues new versions when standard sets change and makes these sets available to others. The ASN is currently owned and operated by D2L, a learning-platform company. TeachEngineering has enjoyed a long-term relationship with ASN and although major differences exist between how TE 1.0 used to and TE 2.0 now uses the ASN, the ASN continues to function as TeachEngineering’s de facto repository of K-12 standards.

Whereas K-12 standard tracking is readily available from services such as ASN, standard alignment; i.e., matching documents with standards, is far more problematic. Although it is not our goal here to thoroughly analyze the standard alignment problem, it is important to know that each TeachEngineering document is aligned with one of more K-12 educational standards and since standards frequently change, these alignments must be regularly updated as well. Chapter 5 covers the differences between TE 1.0 and 2.0 in how they represent and include standards.

Collection Editing and Document Accessioning

Although invisible to TeachEngineering users, TeachEngineering documents do not make it automatically and miraculously into the collection. Instead, they go through a structured review process, first for content and once accepted for content, for editing and formatting. Once a document is ready, it must be ingested into and registered to the collection.

The process starts with TeachEngineering curricular staff and several external reviewers reviewing the submissions for content and compliance on standard TeachEngineering acceptance criteria. Is it engineering? Is it good science? Does it fit the objectives of TeachEngineering? Is it well written? Is it aligned with standards and do the alignments seem reasonable? Is it attractive, both for teachers and students? Is it internally consistent? Are concepts properly explained and procedures well described? Is anything missing? Depending on the answers to these questions, a submission might be refused, conditionally accepted, or accepted as is.

Once accepted, the document must be formatted to fit the TeachEngineering document template. This process changed quite dramatically between TE 1.0 and 2.0. Finally, the now formatted document must be registered to the collection so that it can be searched, displayed, saved as a bookmark, commented on, rated, etc. Chapter 6 covers document accessioning in both the TE 1,.0 and TE 2.0 versions.

System Implementation and Collection Hosting

Just as invisible to TeachEngineering users as the collection editing and document accessioning process, is the collection’s web hosting. Since TeachEngineering is a web-based digital library it must be web hosted and although the general principles of web hosting are the same for both versions 1.0 and 2.0, the specific implementations are quite different. Whereas TE 1.0 was hosted on Linux on an intra-university Linux cloud, TE 2.0 is hosted on Microsoft’s Azure cloud. And whereas TE 1.0 used Google’s Site Search Engine, TE 2.0 uses Microsoft’s Azure Search and whereas TE 1.0’s website was written in the PHP programming language running against a MySQL SQL database, 2.0 was written in C# running against the RavenDB JSON database. These differences are significant and reflect some of the more general developments in web-based technologies as they occurred over the last 5-10 years. We discuss and illustrate these elsewhere in our text.

Extras

In addition to the TE core functions mentioned above, a system such as TE has a number of what we would like to call ‘extras;’ facilities which make life for both the system maintainers and the system users easier. Some of these are the following:

- Facilities where users can store frequently used curriculum or where they can rate and review curriculum.

- Facilities for users to contact the staff; for instance, to report a problem or to ask a question.

- Facilities for the staff to track system use.

- Facilities which aggregate collection information so that at any time TeachEngineering staff can know how many documents of type x or from school y are stored in the collection.

- Facilities which make it easy for users to group and print curriculum.

Once again, both TE 1.0 and 2.0 had these (and other) facilities, but they architected them in different ways.

Continuous Quality Control

A system such as TeachEngineering is on-line and is meant to serve users anywhere in the world at any time. But it is also continuously changing in that new documents come on-line, existing ones are revised, new users register themselves, and users who care and desire to do so can leave comments and ratings behind. Add to that that TE has about 3 million (different) users per year and it becomes clear that a system such as this must be carefully monitored to make sure that it functions properly. And in case it stops functioning properly, technical staff must be alerted and informed about what is wrong so that they can fix the problem. Although both TE 1.0 and 2.0 employed significant amounts of monitoring, they go about it in different ways.

References

Conley, D.T. (2014) The Common Core State Standards: Insight into Their Development and Purpose.

Lima, M. (2011) Visual Complexity. Mapping Patterns of Information. Princeton Architectural Press. New York, New York.

Marshall, B. Reitsma, R. (2011) World vs. Method: Educational Standard Formulation Impacts Document Retrieval. Proceedings of the Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL’11), Ottawa, Canada.

NRC (2012) A Framework for K-12 Science Education. Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

NSF (2010) GK-12: Preparing Tomorrow’s Scientists and Engineers for the Challenges of the 21st Century. Available: http://www.gk12.org/files/2010/04/2010_GK12_Overview.ppt.

NSF-AAAS (2013) The Power of Partnerships. A Guide from the NSF Graduate Stem Fellows in K–12 Education (GK–12) Program. Available: http://www.gk12.org/files/2013/07/GK-12_updated.pdf

Reitsma, R., Diekema, A. (2011) Comparison of Human and Machine-based Educational Standard Assignment Networks. International Journal on Digital Libraries. 11. 209-223.

Reitsma, R., Marshall, B., Chart, T. (2012) Can Intermediary-based Science Standards Crosswalking Work? Some Evidence from Mining the Standard Alignment Tool (SAT). Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 63. 1843-1858.

Sutton, S.A., Golder, D. (2008) Achievement Standards Network (ASN): An Application Profile for Mapping K-12 Educational Resources to Achievement Standards. Proceedings of the International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Berlin, Germany.

Zia, L. (2004) The NSF National Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Education Digital Library (NSDL) Program. D-Lib Magazine, 2, 10:3.