Transnational Feminist Activism Against Gender Violence

Giovanna Vingelli

Abstract

The history of feminism can be read as an effort to construct, through struggle, a unity among women, starting from their common experiences of material and symbolic oppressions (Hunter, 1996). However, since different historical, social, and cultural contexts create different power relations, the experience of being a woman is also different. This explains not only the transformation of feminism over time, but also its differentiation into a plurality of feminisms.

Since the 1990s, transnational feminist movements have been adopting a broad agenda that recognizes the different institutional, economic, and social contexts in which women operate. Transnational feminists engage with local and international powers, joining other movements, but doing so in the “first person”; that is, maintaining their authority and autonomy.

Transnational feminists utilize an intersectional feminism that, while recognizing and honoring their differences, chooses to fight together against the violence of patriarchy, racism, classism, heterosexism, and economic oppression. This transnational perspective rejects the abstract idea of a generic “woman,” as well as a single and universal path of liberation valid for all. Transnational feminists bring together a diversity of issues under a single feminist umbrella, challenging societal assumptions about gender-based violence and holding both society and the state accountable for perpetuating such violence.

Learning Outcomes

- Students will explain the importance of the terms “intersectionality” and “transnational feminism” in the context of the last five decades of feminist action

- Students will describe some of the key changes and realizations that occurred as a result of transnational meetings, documents, organizations, and actions

Contemporary Feminist Activism and the Quest for Intersectionality

Contemporary feminist activism crosses different spatial dimensions, addressing issues at global and local levels. It involves a range of strategies, mobilizing women from different countries around a set of common issues. Within these commonalities, though, the differences in women’s lives are shaped by the positions each occupies based on her markers of identity and her membership in groups.

What does it mean to be a woman? In the 1980s, non-Western feminists began to critique the “abstract universality” assumed in masculine discourses and practices, and also within Western feminism itself; that is, the idea that “all people” or “all women” shared the same set of characteristics and circumstances. The 1980s’ second wave of Western feminism has been criticized for reflecting primarily the interests of white, heterosexual, educated, urban, middle-class women; to the exclusion of members of all other identities, including gender, ethnicity, race, class, sexuality, age and generation, disability, and nationality. In reality, these categories intersect to produce further social inequalities that cannot be resolved using the theory that all women in the world share the same experiences precisely because they are women. The twentieth-century ideal of “universal sisterhood” (Morgan, 1984) contributed to the stereotype of a universal “female,” even when its intention was to denounce misogyny and discrimination against women.

Starting in the 1970s, groups of black women, lesbians, women from “Third World” countries, and women belonging to other minority groups have criticized this Western feminism for its influence on feminist political agendas, disregarding the life experiences of other women. In the late 1970s, the Combahee River Collective (CRC) issued a statement describing the notion of “multiple oppressions,” drawing on the experiences of black women, and including race, gender, sexuality, and class oppression (Combahee River Collective, 2018). It conceived of oppression as the combined effects of multiple, complex systems of subordination.

The concept of “woman,” then, in feminist struggles has been presented as “universal,” but has actually taken the specific form of the Western feminist—which clearly contradicts the objectives of the feminist movement, which was born out of the need to oppose a false universalism: that of the generic, dominant male, seen as the “norm” or center, in contrast to all “other” social positions.

Thus, feminists became aware that adding a generic or universal “woman” to a generic “man” did nothing more than duplicate already-existing power differentials. “Black feminism” and “lesbian feminism” began differentiating women’s political standpoints on the basis of sexual choice and ethnic and cultural affiliation, allowing a shift in focus to “multiple oppressions” (Weathers, 1969), or “double colonisation” (Spivak, 1988; 1999).

Thinking of women as a homogeneous and monolithic category had already had its negative effects: in her book Ain’t I a Woman (1981), bell hooks, among others, had denounced the way in which white, Western feminists had neglected and erased the different needs of non-western women. In this way, she argued, racism, classism, and ethnocentrism were reinforced within the feminist movement itself, to the detriment of women.

Chicana and lesbian author Gloria Anzaldúa illustrated (1987) how Chicana women are even the victims of triple, if not quadruple, discrimination: racial, because of their color and ethnicity; class, because they are economically disadvantaged; gender, because they are women; and possibly sexual orientation. Faced with this knot, we need to think of a feminism based on the recognition of the different levels of reality women experience, to propose “a feminist solidarity as opposed to vague assumptions of sisterhood or images of total identification with the other” (Mohanty, 2003, p. 3). It is the examination of these realities that animates intersectionality: a complex and contested concept, but one that, since its beginning around the 1990s, has proved useful as a theoretical, conceptual, and political tool for sorting through the multiple and simultaneous aspects of women’s oppression.

Moving to Intersectional Viewpoints

As these key ideas about the complexity of inequality were developing within black women’s political activism, Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) coined the term “intersectionality,” defined as “a complex system of multiple, simultaneous structures of oppression” (Crenshaw et al., 1995, p. 359). She specified that structural intersectionality refers to the overlapping factors relevant to people’s experiences in society. For example, gender-based violence is experienced differently by white women and black women. Political intersectionality refers to how political strategies that address one axis of oppression cannot ignore other factors. For example, feminist movements fail women of color if they do not acknowledge issues of racism.

INTERSECTIONALITY

- Sexuality

- Ethnicity

- History

- Heritage

- Education

- Language

- Gender

- Class

- Religion

- Age

- Race

Patricia Hill Collins, a feminist scholar who has adopted the intersectional model, posits that race, class, and gender are “interlocking systems of oppression” (1993). She writes that “the sexual politics of Black womanhood reveals the fallacy of assuming that gender affects all women the same way—race and class matter greatly” (2000, p. 229).

Crucial Understandings for Feminist Cooperation

Coined by Kimberlé W. Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality is rooted in the research and activism of women of color, extending back to Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” speech in 1851.

Observing the absence of women of color in feminist and race-based social movements, scholar activists like Crenshaw, bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Cherríe Moraga have called for a deeper look at the interconnected factors that influence power, privilege, and oppression.

Now more than ever, it’s important to look boldly at the reality of race and gender bias—and understand how the two can combine to create even more harm. As Crenshaw says, if you’re standing in the path of multiple forms of exclusion, you’re likely to get hit by both. She calls on us to bear witness to this reality and speak up for victims of prejudice.

Transnational feminism takes into account women’s experiences on a global scale by focusing on intersectionality, colonialism, and imperialism. The theories and practices of this movement seek to understand how race, gender, social class, culture, and sexuality are affected on a global scale. While the term “global feminism” favors a universalized model of women’s liberation that celebrates individuality and modernity, the term “transnational,” meaning “across borders,” recognizes inequalities arising from women’s differences and is committed to activism that encourages dialogue for change.

An example of transnational feminism can be seen in Chimamanda Adichie’s video “The Danger of a Single Story.” Adichie is a Nigerian novelist and writer who has won numerous awards for her work. In her TED Talks video, she says that hearing only one story about someone/someplace is very limiting and creates unnecessary stereotypes. Our lives, our cultures, are composed of many overlapping stories. Adichie tells the story of how she found her authentic cultural voice—and warns that if we hear only a single story about another person or country, we risk a critical misunderstanding.

Since every person belongs to more than one social category, and these categories interact both at the individual level and at the level of groups and institutions, it is necessary to consider the relationships between them; to analyze their “intersections” (Crenshaw, 2011) or “intersections between axes of power” (Yuval-Davis, 2006). Intersectional analysis suggests that “combinations” of identity factors are not mere overlaps, but produce significant and substantively specific experiences of oppression and privilege for different women.

In an intersectional approach, the primary focus is not on individual differences, but on their political recognition. In this view, differences are not set against each other, but juxtaposed: not hierarchically, but simultaneously.

Transnational Feminist Theories and Practices

These reflections and theorizations have been fundamental to the emergence of the “third wave” of feminism, which starts from the inescapable reality of differences between women, and thus the existence of multiple feminisms. Contemporary feminisms have produced a new form of theorizing reflecting on the never “neutral” position from which our subjectivity is formed. What is being questioned is the universalist concept, according to which all women, as women, are fundamentally equal, with the same history of oppression and the same desires. A type of feminism that is situation-specific and constantly changing then becomes the starting point of transnational feminism, which takes an intersectional approach to analyzing the oppressions and inequalities an individual suffers, taking into account the social, economic, religious, and political contexts in which they live.

Transnational feminist theory and practice emphasize intersectionality, interdisciplinarity, social activism and justice, and collaboration. They seek to highlight social structures that increase power differentials, including colonialism and neo-colonialism, economic realities, and global capitalism: “This project stems from our work on theories of travel and the intersections of feminist, colonial and postcolonial discourses, modernism and postmodern hybridity” (Grewal & Kaplan, 1994, p. 1).

The term “transnational” is an umbrella term that has emerged as “a way of naming the dramatically increasing flows of people, things, images and ideas across nation-state borders in the era of ‘globalisation’” (Conway, 2019, p. 43). Transnational feminist perspectives focus on the diverse experiences of women living within, between, and on the borders of nation-states around the globe. These perspectives transcend nation-state boundaries because of the many interacting geopolitical forces affecting women’s experiences. They also involve communication across traditional global, regional, and local boundaries. They include the experiences of immigrants, refugees, displaced persons, those who have experienced forced migration, members of a cultural diaspora who may be dispersed across multiple regions, as well as those who identify as third culture, and those who seek to integrate multiple cultural identities (Horne & Arora, 2013). Transnational practice may take place in women’s nations or cultures of origin, in cultures in which they are displaced or immigrants, or in settings in which they are temporary sojourners. It also includes the experiences of women living in cultural borderlands and intercultural spaces (Zerbe et al, 2021).

If the idea of “global sisterhood” (Morgan, 1984) assumed women’s commonalities; transnational feminisms, on the contrary, assume women’s differences. Mohanty (2003) emphasises the need for feminists to theorize in new and deeply contextualized ways about alliances and solidarity, and the urgency of an anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and post-colonial feminist project promoting mutuality, accountability, and the recognition of common interests as the basis for relationships between diverse communities.

Transnational feminist practices thus call for work comparing women’s multiple oppressions and their intersections, rather than focusing on a theory of oppression using the universal category of “women,” abandoning the idea of constructing a unified feminist agenda (Basu, 1995). In this way, Mohanty proposes a “feminism without borders” as a strategy for addressing the injustices of global capitalism and opening up new possibilities: “it is through this model that we can put into practice the idea of common difference as the basis for deeper solidarity across differences and unequal power relations” (Mohanty, 2003, p. 250).

The Genesis of Transnational Feminism

Transnational feminism differs from global feminism and international or intra-national feminism in that it examines the complexity of women’s identities as they are formed by the intersections of national identity, race, sexuality, and specific forms of economic exploitation. Transnational feminism can be traced back to 1975, the year of the first UN Conference on Women, in Mexico City. This event—which was the result of the changing international context following colonization, and which had its origins in the explosion of the feminist movement in the West and the large presence of women in the liberation movements of many countries in the South (Rai, 2002)—was of enormous value because it allowed more than 6,000 women to participate in the “civil society forum,” beyond the official delegations of each nation. While North American and European women prioritized the achievement of equality and issues of sexual rights and reproductive freedom, Latin American women preferred to focus on issues of material oppression, i.e., poverty, neo-colonial domination (the control exerted by a more powerful nation over a less powerful one), and war.

Learning Activity:

Feminist Waves and Parallel Timelines

Objective: Students will analyze the limitations of the wave model of feminism and describe the importance of a global and intersectional approach to understanding feminist history. Through the use of parallel timelines, students will connect feminist movements globally across time and space.

- Divide the class into two groups (A and B). Each group will focus on creating a timeline that compares and contrasts feminist movements in the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere of the World.

- Group A: Northern Hemisphere. Choose up to 10 countries using this list: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/northern-hemisphere-countries

- Group B: Southern Hemisphere. Choose up to 10 countries using this list: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/southern-hemisphere-countries

- Divide the larger groups into small groups of two or three people. Have each smaller group focus on one to two countries. Create a timeline of feminist movements in the countries you have chosen. Make sure to note any overlaps in feminist movements if the countries neighbor one another or have a significant political interaction with one another.

- Have each of the larger groups (A and B) present their findings to the class by writing key timeline information under the headers Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere. Identify parallels between the timelines you have uncovered. Pay close attention to the ways in which the wave model either highlights or obscures the information you have found.

The second UN Conference, in Copenhagen (1980), would reveal even more this conflict between different political standpoints among different groups of women, the complexity of their situations that were completely different for cultural, economic, and political reasons. In those years, the international context was profoundly shaken by the breakdown of the old balances between the West, the Communist world, and what was still defined as the “Third World” (that is, countries that were unaligned with either the West or with Communism during the Cold War. A more accepted term today is “developing countries”). This general climate of change led the women gathered in Copenhagen to abandon the “common denominator” of “gender” and instead to focus on different cultural and political affiliations in interpreting the causes of the enormous gap that was widening between rich and poor countries.

In fact, for many of the participants, especially those from the global South, the demand for gender equality took a back seat to the problem of increasing poverty experienced by women in their countries. This fundamental disagreement was at the origin of the conflict between the still few Southern feminists and Western, especially American, feminists; but it also became a powerful instrument for the cultural and political growth of the transnational women’s movement. In fact, the clash had the effect of multiplying the transnational networks of women from different continents and of deepening the critical analyses, in particular of the ecofeminists (Mies & Shiva, 1993) and of the DAWN group (Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era) (Sen & Grown, 1987), which were active throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.

A Turning Point

Based on analyzing the cultural and economic relationships among women, men, and the management of natural resources, feminists began to critique the emerging neoliberal development model, focused solely on “economic growth” (essentially, industrial progress) and disregarding the human and environmental sustainability of development processes. These analyses were often at odds with the working methods of the major international financial institutions, especially the World Bank and the World Trade Organization.

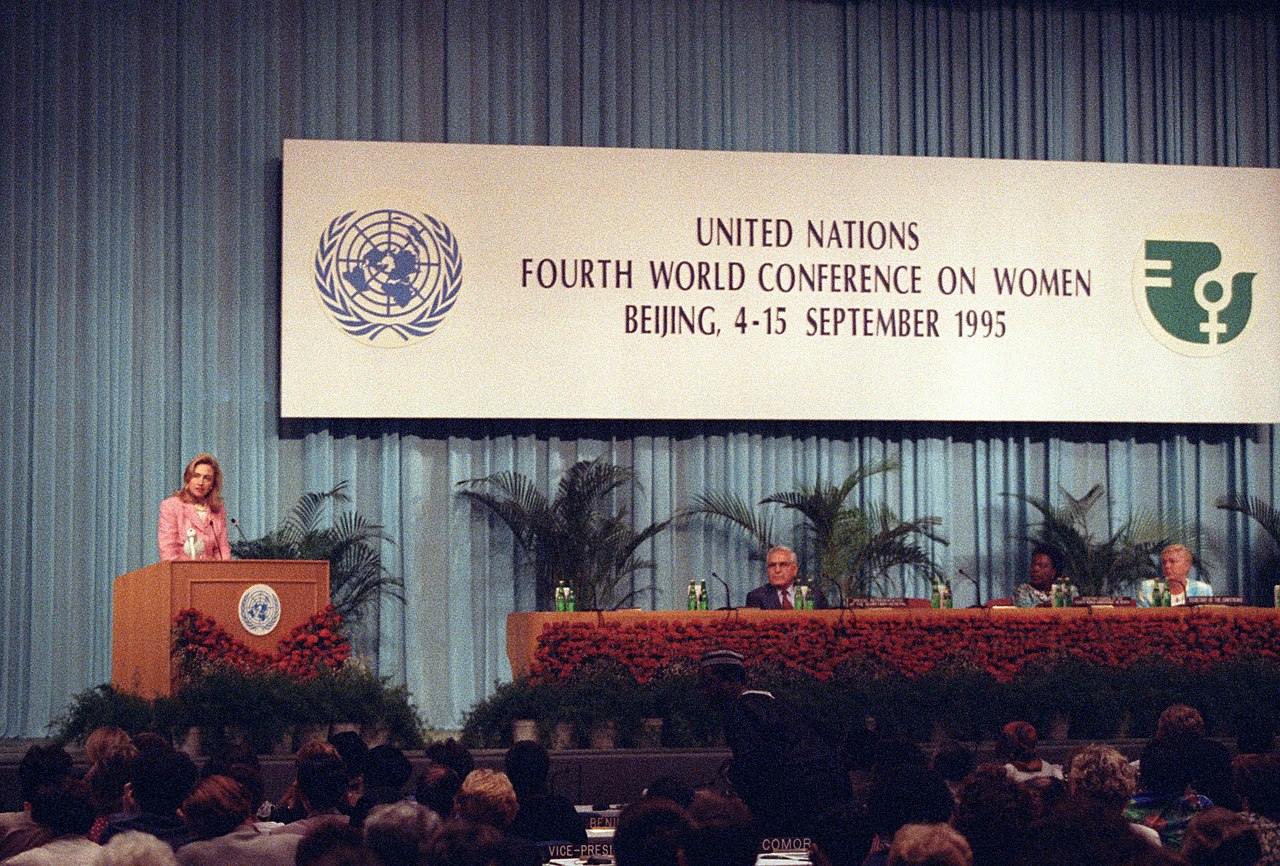

The debates surrounding the Platform of the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 marked a turning point in favor of a transnational approach to feminist movements. Although, on the one hand, the debates were tangible evidence that feminist movements were diverse and conflicting in practice as well as theory; on the other hand, the scale of global change in the 1990s[1] also led to a convergence of feminist perspectives and the emergence of transnational movements and alliances, bringing together women from North and South to respond to these pressures.

Transnational Mobilization and Violence Against Women

An early example of a mobilization that could be described as transnational was the World March of Women Against Poverty and Violence (WMV), launched in 1998 by the Fédération des Femmes du Québec in Montreal, Canada. This event culminated in the year 2000 in a series of other marches and actions organized around the world to protest against poverty and violence against women. Nearly 6,000 organizations from 159 countries participated in these demonstrations, and the issues raised were of course diverse and varied, depending on their contexts. Five years later, after the first World March in 2000, the WMV committee launched the Women’s Global Charter for Humanity to answer a number of questions: How do we want to build a new world order? What are the prerequisites for this transformation? The Charter contains 31 “affirmations” on the themes of peace, justice, solidarity, and equality; values to be followed to create the “other world” envisioned by the WMW (Dufour & Giraud, 2007).

The interesting thing about the drafting of this document, in contrast to the previous documents produced by the UN conferences, is its circularity: the document underwent a real journey around the world so the various national committees could read, modify, and complete it. The journey began in Brazil and ended in Burkina Faso in 2005. Moving from one country to another (and therefore from one context to another) highlighted the differences both in perspective and in approach to the issues at stake, the desire to pursue a common and effective project, and the will to build a global movement with a collective identity (Dufour & Giraud, 2007); but without overriding the will of the individual context. In order to achieve this unity, a series of compromises were accepted through dialogue, both on the issues to be addressed and on the methods of implementation (Moghadam, 2005).

Feminists and women’s groups have also long been involved in peacebuilding, identifying methods of conflict resolution, and creating the necessary conditions for human security. The activities of anti-military and human rights groups such as Women Strike for Peace[2], Greenham Common,[3] and Madres y Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo[4] are the best known. These groups, as well as many others emerging in response to the wave of conflicts dramatically highlighting the abuses and violence of war (Afghanistan, Bosnia, Central Africa, the Middle East), focus their attention on the particular vulnerabilities of women and girls in war, the widespread nature of sexual abuse, and the need to include women’s voices in peace negotiations.

A New Phase

The transformation brought by the 2008 economic crisis is the driving force behind an equally significant transformation of feminism: “this is a moment in which feminists should think big. Having watched the neoliberal onslaught instrumentalize our best ideas, we have an opening now in which to reclaim them. In seizing the moment, we might just bend the arc of the impending transformation in the direction of justice—and not only with respect to gender” (Fraser, 2009, p. 117). It is precisely in recent years that Fraser identifies a new feminist phase, a rebirth of a radical and rebellious women’s movement, linked to the visionary potential of the first wave of feminism, although starting from different assumptions, conditions, and goals.

This phase involves new technologies, the existence of a global network of users, and the emergence of “mass self-communication” (Castells, 2009). In this context, the Internet plays a crucial role in promoting the expansion of the public sphere, both locally and globally. New forums for social interaction, alternate types of activism, and the formation of new collective identities are being constituted online. The expanded possibilities for truly global networking have marked the beginning of a new era for social movements. Cyber-activism is often defined as unconventional political action, where “unconventional” means alternative tactics and expressions to traditional political structures, common in movements such as feminism (Rucht, 1990). Social media play a crucial role in the emergence of these new social movements, which benefit from the expanded possibilities of interaction, the low cost of this type of communication, and the speed of creating and disseminating messages to a potentially huge community of users.

Two mobilizations, SlutWalk and Ni Una Menos (Not One Women Less), could serve as examples of practices that combine old and new political and communicative tools to mobilize against violence against women, using this new wave of social movements. SlutWalk was born in 2011 in Toronto, Canada. The first SlutWalk march was organized in response to prejudices, behavior, and dress codes that blamed women and reinforced a misogynistic and patriarchal culture that generated violence. Although the SlutWalk protests and demonstrations were spontaneous, they have spread around the world and gained much success and support. In 2011 alone, protests took place in over 200 cities and at least 40 countries, including Spain, Hungary, Finland, Norway, South Korea, South Africa, Australia, Ukraine, Mexico, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Germany, Morocco, and England (Carr, 2018).

The strategy of the marches is very clear: instead of submitting to social norms about how to dress and behave in public, women use insults and accusations instrumentally and to their own advantage, with two main goals: to attract media attention and to advance women’s causes, this time completely independent of governments. This new form of activism emerged at the same time as Occupy Wall Street and the occupations that characterized the Arab Springs (2011), marking a new mode of action and protest with a transnational character.

Since 2008, another new feminist movement has taken center stage on the international political scene. It began with the Spanish Decido Yo movement for the right to abortion, and it has spread to many countries, from the pro-choice protests in Poland and Argentina, where Ni Una Menos was born[5], to the marches in the United States after Trump’s election. Another step in the international feminist movement was the construction of the feminist strike, which in some countries, such as Spain, Chile, and Argentina, succeeded in establishing real blockades and people abstaining from productive and reproductive activities.

Although the feminisms mentioned above deal mainly with their own national contexts, they are united by the same interpretation of violence, by similar struggles to prevent and combat patriarchal violence in the broadest sense; that is, ranging from interpersonal to institutional violence. As Segato (2022) notes, characterizing gender-based violence as a war against female and feminized bodies allows for a comprehensive and interdisciplinary analysis of the underlying mechanisms that produce these forms of violence, which are particular and embodied.

The Argentinian feminist movement took to the streets of Buenos Aires and 120 other cities across the country on June 3, 2015, in response to the femicide of Chiara Páez, a 14-year-old girl, with over 200,000 people taking to the streets in the capital alone (Daby & Moseley, 2022).

Since the first document (Manifesto 3 de junio 2015), and in subsequent demands, Argentinian women have addressed the issue of femicides (given the dismaying numbers in their country) from an exquisitely feminist perspective, i.e., they emphasize that femicide is not an intimate issue, related only to the domestic sphere, or a problem that affects only women; rather, it affects the whole of society. Violence against women is a form of structural violence, and not a phenomenon limited solely to one’s social class, level of education, or geographical location.

“Ni Una Menos” translates as “Not one [woman] less” and is often stylized as #NiUnaMenos due to the viral nature of the movement. Ni Una Menos is a horizontal movement, made up of different groups within countries and different branches between countries, each related to the others but independent in their actions.

In the countries where Ni Una Menos has spread, in addition to purely national issues and demands, some demands are the same: the collection and publication of official statistics on violence against women, including rates of femicide; more emergency shelters and day homes for victims of gender-based violence, along with housing subsidies to help victims achieve autonomy; the incorporation and deepening of comprehensive sexual education curriculum at all education levels; and mandatory training for government actors on the subject of sexist violence.

Ni Una Menos also shows how activists in the Global South can promote new uses of technology that not only respond to their local and immediate needs, but also contribute to the production of alternative imaginaries of big data in the longer term. The Ni Una Menos mobilization created the first “Índice nacional de violencia machista” (National Index of Male Violence) to address the lack of data and public policies on gender violence in the country.

Summary

The new feminist wave is bringing together broad demands for rights, based on a reading of the current conditions and needs of women. A new awareness has emerged of the need to rebuild bonds of solidarity, action, and collective struggles against the constant attacks on bodies, freedom, and self-determination. What this transnational movement is somehow doing is raising awareness of the stratification of women’s social status according to class, origin, “race,” and sexual orientation.

The model of comparative feminist studies proposed by Mohanty is particularly helpful because it does not focus on a single fixed theory, and thus offers more options for grasping the complexities of gender in the globalized world (Mohanty, 2003). It reminds us that the local and the global are interrelated and mutually supportive. Such a comparative framework also accepts the intersections of race, class, nation, gender, and sexuality; and an analysis of the different, intertwining, historical experiences of oppression. At the same time, this view involves examining the potential for solidarity and mutuality in struggle, at individual and global levels. Thus, the tasks of feminists should be constantly re-imagined by “transcending the conceptual borders inherent in the old cartographies” (Shohat, 2001, p. 1272), and by reaching across national borders and other boundaries to create mutual support.

Review Questions

Questions for Reflection

- Various forms of privilege can obscure differences between women and make it harder for people of different perspectives to engage in feminist spaces. How does your social context influence your perceptions of race, class, and gender? In your context, what are the formal and informal norms that perpetuate privilege in feminist movements?

- How do Western frameworks of gender violence often reinforce stereotypes and fail to account for cultural relativism, particularly in their tendency to focus on violence abroad, while excusing domestic violence? Why is it important to adopt a transnational feminist approach to understanding gender violence that resists centering Western ideological perspectives? Discuss the implications of this approach for analyzing gender violence globally and challenging the dominant narratives upheld by the US settler-state.

- The wave framework of feminism divides the movement into distinct phases (first, second, third, fourth) that are largely centered around Western feminist efforts and moments in history. How does this framework obscure global feminist movements, particularly in the Global South? What are the consequences of focusing on a wave model in discussions of feminist history?

References

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La frontera: The new Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

Arditti, R., & Brinton Lykes, M. (1992). Recovering identity: The work of the grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo. Women’s Studies International Forum, 15(4), 461-471. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-5395(92)90080-F

Basu, A. (Ed.). (1995). The challenge of local feminisms: Women’s movements in global perspective. Westview Press.

Carr, J. L. (2013). The SlutWalk Movement: A study in transnational feminist activism. Journal of Feminist Scholarship, 4, 24-38. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol4/iss4/3

Castells, M. (2009). Communication power. Oxford University Press.

Collins, P. H. (1993). Toward a new vision: Race, class, and gender as categories of analysis and connection. Race, Sex, & Class, 1(1), 25-45.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Combahee River Collective. (2018). A black feminist statement: Combahee River Collective. In P. Weiss (Ed.), Feminist manifestos: A global documentary reader (pp. 269-277). New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479805419.003.0063

Conway, J. M. (2019). The transnational turn: Looking back and looking ahead. In L. H. Collins, S. Machizawa, & J. K. Rice (Eds.), Transnational psychology of women: Expanding international and intersectional approaches (pp. 43–60). American Psychological Association.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989 (1, Article 8), 139-167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Crenshaw, K. (2011). Postscript. In H. Lutz, M. T. Herrera Vivar, & and L. Supik (Eds.). Framing intersectionality: Debates on a multi-faceted concept in gender studies (pp. 221-233). Ashgate.

Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., Peller, G., & Kendall, T. (1995). Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. The New York Press.

Daby, M., & Moseley, M. W. (2022). Feminist mobilization and the abortion debate in Latin America: Lessons from Argentina. Politics & Gender, 18(2), 359-393. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000197

Dufour, P., & Giraud, I. (2007). The continuity of transnational solidarities in the World March of Women, 2000 and 2005: A collective identity-building approach. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 12(3), 307-322. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.12.3.tv24474575l71807

Essayag, S. (2017). From commitment to action: Policies to eradicate violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional analysis document. United Nations Development Programme & UN Women. https://lac.unwomen.org/en/digiteca/publicaciones/2017/11/politicas-para-erradicar-la-violencia-contra-las-mujeres-america-latina-y-el-caribe

Fraser, N. (2009). Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Columbia University Press.

Grewal, I., & Kaplan, C. (Eds.). (1994). Scattered hegemonies: Postmodernity and transnational feminist practices. University of Minnesota Press.

hooks, b. (1981). Ain’t I a woman: Black women and feminism. South End Press.

Horne, S. G., & Arora, K. S. K. (2013). Feminist multicultural psychology in transnational contexts. In C. Z. Enns & E. N. Williams (Eds.), Oxford handbook of feminist multicultural counseling psychology (pp. 240-252). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199744220.013.0013

Hunter, R. (1996). Deconstructing the subjects of feminism: The essentialism debate in feminist theory and practice. Australian Feminist Law Journal, 6, 135-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13200968.1996.11077198

Mies, M., & Shiva, V. (1993). Ecofeminism. Zed Press.

Moghadam, V. M. (2005). Globalizing women: Transnational feminist networks. The Johns Hopkins University Press. https://doi.org/10.56021/9781421442815

Mohanty, C. T. (2003). Feminism without borders: Decolonizing theory, practicing solidarity. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822384649

Morgan, R. (Ed.). (1984). Sisterhood Is global: The international women’s movement anthology. Random House.

Rai, S. M. (2002). Gender and the political economy of development: From nationalism to globalization. Polity Press.

Roseneil, S. (1995). Disarming patriarchy: Feminism and political action at Greenham. Open University Press.

Rucht, D. (1990). The strategies and action repertoire of new movements. In R. J. Dalton & M. Kuechler (Eds.), Challenging the political order. New social movements in western democracies (pp. 156-175). Oxford University Press.

Segato, R. (2022). The critique of coloniality: Eight essays (R. McGlazer, Trans.). Routledge.

Sen, G., & Grown, C. (1987). Development, crises, and alternative visions: Third World women’s perspectives. Routledge.

Shohat, E. (2001). Area studies, transnationalism, and the feminist production of knowledge. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 26(4),1269–1272. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/495659

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture. (pp. 271-313). University of Illinois Press.

Spivak, G. C. (1999). A critique of postcolonial reason: Toward a history of the vanishing present. Harvard University Press.

Swerdlow, A. (1993). Women strike for peace: Traditional motherhood and radical politics in the 1960s. University of Chicago Press.

Weathers, M. A. (1969). An argument for Black women’s liberation as a revolutionary force. Caring Labor: An Archive (Originally published in No More Fun and Games: A Journal of Female Liberation, 1(2), 67-130. https://caringlabor.wordpress.com/2010/07/29/mary-ann-weathers-an-argument-for-black-womens-liberation-as-a-revolutionary-force/

Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Intersectionality and feminist politics. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(3),193-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506806065752

Zerbe Enns, C., Díaz, L. C., & Bryant-Davis, T. (2021). Transnational feminist theory and practice: An introduction. Women & Therapy, 44(1-2), 11-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2020.1774997

Further Learning

Adichie, C. (2009, July). The danger of a single story [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

Baumgardner, J. (2011). Is there a fourth wave? Does it matter? feminist.com. https://www.feminist.com/resources/artspeech/genwom/baumgardner2011.html

Butts, T., Duncan, P., Lockhart, J., & Shaw, S. (2022). Women worldwide: Transnational feminist perspectives (2nd ed.). Oregon State University. https://open.oregonstate.education/womenworldwide/

Crenshaw, K. (2021, November 18). Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality | The big idea [Video]. YouTube. https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?q=crenshaw kimberle&mid=A9974692ADEC745F1319A9974692ADEC745F1319&FORM=VIRE

Índice Nacional de Violencia Machista [National Index of Male Violence]

Mohanty, C. T. (1991). Third world women and the politics of feminism. Indiana University Press.

Moser, C. O. (1993). Gender planning and development. Theory, practice and training. Routledge.

Media Attributions

- Intersectionality Figure © OERU is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 4.0 license

- Hillary_Rodham_Clinton_Fourth_United_Nations_Conference © National Archives and Records Administration is licensed under a Public Domain license

- MDP_Greenhamcommon1982 © Rabbitspawphotos is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) 3.0 license

- 5827982413 © Newtown grafitti is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 2.0 license

- 3J_En_Santa_Fe_Ni_Una_Menos_2022_(1) © Misscoloreta is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) 4.0 license

- The transformation of the 1990s was particularly influenced by three economic and political transformations that took place both nationally and globally. The first was the transition from Keynesian economic policies (with their emphasis on state intervention to achieve full employment and the welfare of citizens) to the neo-liberal economic order (with its emphasis on the free market, privatization, and trade and financial liberalization), together with a new international division of labor based on women’s labor. The second is the slow decline of the welfare state in all First World countries and the persistence of poverty and underdevelopment in many Third World countries, both of which have taken a heavy toll on women’s reproduction and the management of domestic roles. Third, the emergence of various forms of fundamentalism and right-wing religious movements that threaten women’s autonomy and human rights. ↵

- On November 1, 1961, an estimated 50,000 women in 60 U.S. cities answered a call to join a one-day strike with the rallying slogan “End the Arms Race—Not the Human Race.” After less than two years of activity, the movement shared a significant victory when the Limited Test Ban Treaty, banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere and outer space and under water, entered into force on October 11, 1963 (Swerdlow, 1993). ↵

- From September 1981, for almost 20 years, women from around the UK and beyond descended on Berkshire against the storage of American nuclear missiles on UK common land. The first women arrived on the 3rd of September, 36 having had marched all the way from Cardiff. Others joined them on the way, and over the years that followed, many thousands joined them. Together, they created the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, an exclusively female space; and they thrived together, pushing those watching to question war, violence, sexual orientation, and gender roles (Roseneil, 1995). ↵

- The Association of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo formed in 1977 in Argentina to seek the restitution of more than 400 children kidnapped or born in captivity during the 1976–1983 dictatorship (Arditti & Brinton-Lykes, 1992). ↵

- The pro-choice and gender activism in various Latin American countries, including Argentina, Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Brazil, highlights the ongoing issue of high rates of femicide in the region, despite the establishment of the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence Against Women by the Organization of American States in 1994. According to data from the UNDP & UN Women, 14 of the 25 highest rates of femicide globally were in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2017. ↵