Technology-Driven Gender Violence

Virginija Jurėnienė

Abstract

Learning Outcomes

- Students will define the concept of technological violence, identify the levels at which technological gender violence intersect, and describe the various types of technological gender violence

- Students will analyze the causes, prevalence, and impacts of technological violence against women, LGBTQIA+ people, and children

- Students will identify the motives and behavior of technological abusers

- Students will distinguish between the positive and negative consequences of technological progress

- Students will describe the effects on victims of technological gender violence

- Students will provide some examples of resistance/protection against technological gender violence

Definitions and Causes of Gender Violence

The links between gender violence (GV) and technology are nothing new. The 1938 play “Gas Light” presented a vivid illustration of a Victorian husband’s technologically facilitated abuse through his manipulation of household gaslights, to flicker and dim at unexpected times, with the aim of making his wife doubt her own sanity. The term “gaslighting” is now widely used to refer to psychological abuse where the abuser uses false or distorted information to make their victim doubt their own memories and judgements (Barter & Koulu, 2021).

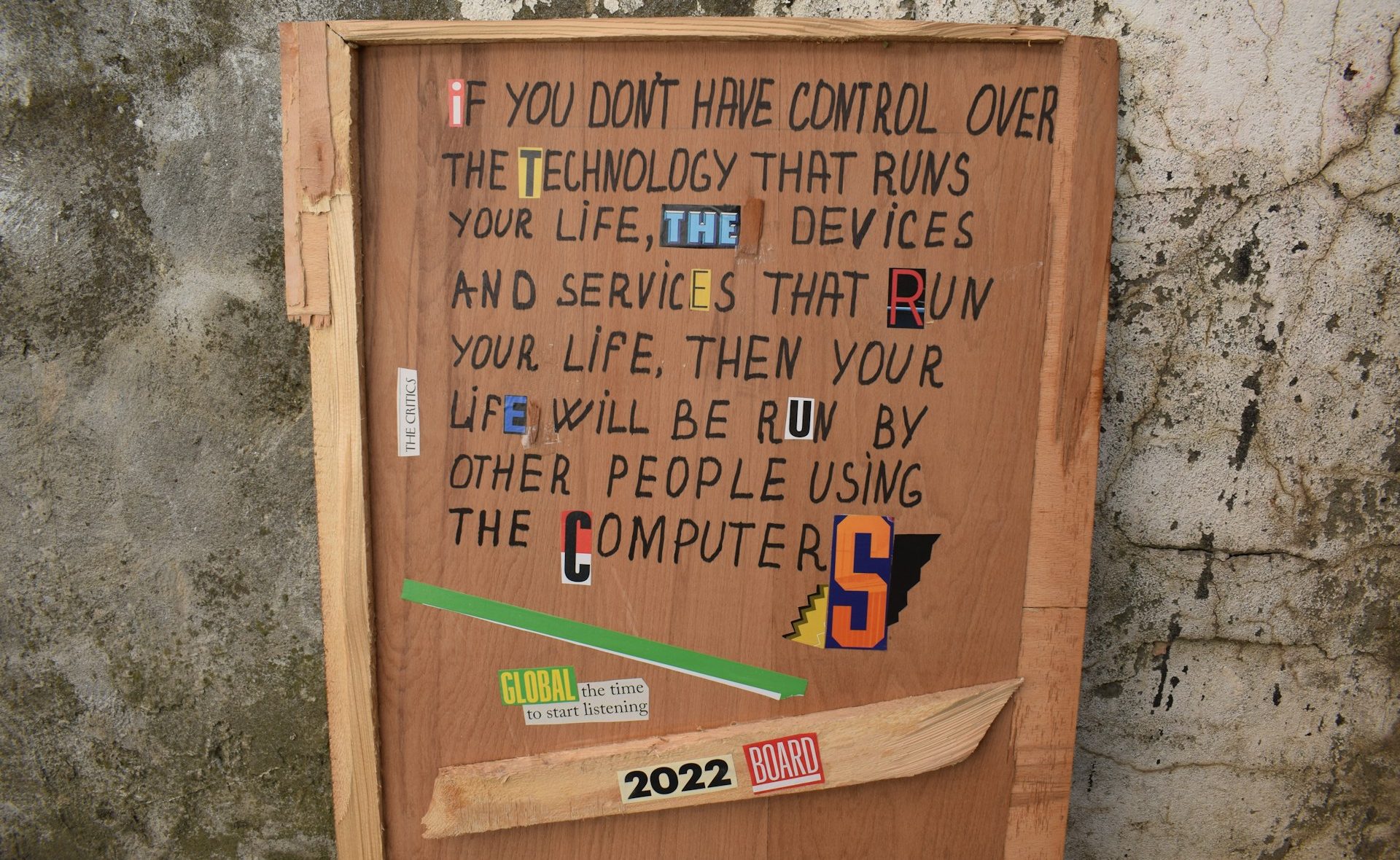

From the first half of the 20th century to the present day, society has developed very rapidly. Technological progress has had a major impact on its transformation (from traditional industrial to post-industrial). The latest technological advances were the beginning of the era of the computer, the internet, robotics, and artificial intelligence. These are commonly known as the fourth and fifth industrial revolutions. As technology changes, so does society. Post-industrial society is described as a society of smart technologies, knowledge, and creativity. However, together with technology, it has been and is changing the relationships between people, not only in a positive sense, but also in a negative sense. The negative uses of technology are sexual and technological violence against LGBTQIA+ people, women, and children.

Digital technologies and gender violence (GV) interconnect at two levels:

- Interpersonal (our personal and intimate relationships with partners, family, friends, peers, colleagues)

- Structural (our communication and interface with social institutions and state infrastructure). Violence is built into the structure and shows up as unequal power and consequently as unequal life chances

GV at the individual level reflects and reinforces structural dynamics such as sexism and racism. At the beginning of the 21st century, many laws have been passed at the international level by UNESCO, the European Commission, the European Parliament, and at the level of nation states to prevent gender violence against children. However, in the last decade, there has also been a great deal of attention paid not only to physical, emotional, psychological, and financial violence, but also to technological violence.

Currently, a large part of the legislative and societal response to all types of violence is focused on the technological, and especially on online platforms where different forms of violence and abuse take place, including social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn), online content and discussion sites (e.g., Reddit), search engines (e.g. Google), messaging services (e.g., Whatsapp, Facebook Messenger, Snapchat, WeChat, Skype), blogs, dating sites and apps, media and newspaper comment sections, forums (e.g. 4chan), online video game chat rooms, etc.

| Authors | Concept |

|---|---|

| International Center for Research on Women (Hinson et al., 2018) | Technology-facilitated gender violence is action by one or more people that harms others based on their sexual or gender identity or by enforcing harmful gender norms. This action is carried out using the internet and/or mobile technology and includes stalking, bullying, sexual harassment, defamation, hate speech, and exploitation. |

| UN Women (2025) | Technology-facilitated gender violence is any act that is committed or amplified using digital tools or technologies causing physical, sexual, psychological, social, political, or economic harm to women and girls because of their gender. |

Digital violence can aggravate offline forms of violence—including sexual harassment, stalking, intimate partner violence, trafficking, and sexual exploitation—through the use of digital tools like mobile phones, GPS, and tracking devices. For instance, traffickers often use technology to profile, recruit, control, and exploit their victims (UN Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022).

The UN report Technology-Facilitated Gender Based Violence stated that the impact of digital violence can be as harmful as offline violence, with negative effects on the health and wellbeing of women and girls as well as serious economic, social, and political impacts (UN Women, 2023a). Digital violence can limit the participation of women online, thus increasing the digital gender divide and limiting women’s voices. ITU reported that there is a significant concern given that the majority of the estimated 2.9 billion people who remain unconnected to the internet are women and girls (International Telecommunication Union, 2023a).

In its report Global Evidence on the Prevalence and Impact of Online Gender-based Violence (OGBV), the Institute of Development Studies stated that between 16 and 58% of women have experienced technology-facilitated gender violence (Hicks, 2021). Thus, the evidence shows that women and girls are disproportionately affected by technological violence. There are also groups of women identified as being at higher risk of online violence, such as:

- Young women and girls

- Women in public life

- LGBTQIA+ people

- Racial, minority, and migrant women groups

- Women with disabilities (UN Women, 2023b)

However, access to digital technologies must also be taken into consideration, as different parts of the world do not have the same level of internet availability and access to digital infrastructure, including connectivity and broadband speeds, access to digital devices, disability and digital literacy, lack of computer equipment or even smartphones. The latter are mostly not available to girls and women in developing countries. In 2022, 2.7 billion people still lacked internet access. Globally, 70 per cent of men are using the Internet, compared with 65 per cent of women—both slight increases from 2022 figures—but women account for a disproportionate share of the global offline population, outnumbering male non-users by 17 per cent. The gender gap is even more concerning in lower-income nations in which 21 per cent of women are online compared to 32 per cent of men, a figure that has not improved since 2019 (International Telecommunication Union, 2022a, 2022b, 2023b). It can be assumed that emerging new technologies and increasing amounts of information will widen the gap between women from different social strata and different countries of development, but will also reduce opportunities for their accessibility and use, while at the same time creating conditions for the technological and online exploitation of women.

In their 2015 wake-up call, the United Nations reported that globally, three-quarters of women online have been exposed to some form of cyber violence, with nine million women in 28 European countries being victimized (Duhaime-Ross, 2015). We have also seen how state apparatus has been used to censor women’s digital self-expression; for example, the Egyptian public prosecutors’ aggressive targeting and prosecution of female TikTok influencers for violating public morals, while Egyptian men routinely receive immunity for sexual violence (Barter & Koulu, 2021; Begum, 2021).

Lack of computer skills for girls and women will make it difficult for them to enter the labor market. And once they do, they will be unable to take up more demanding jobs, as the digital age requires not only a good knowledge of IT as a user, but also as a developer of its programs. The latest global data confirm ongoing challenges preventing women from equally engaging in dynamic and innovative economic sectors. Women are two times less likely than men to know a computer programming language, based on data from 62 countries and areas with data from 2017 or later. In 2022, inventors listed on international patent applications were five times less likely to be female than male. In 2020, women held only one in three research positions worldwide; and only one in five science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) jobs. Their absence in the emerging AI industry has already had an adverse impact on how well this technology supports women and responds to their needs. Facial and voice recognition systems, for example, predominantly designed by men, are more adept at recognizing male voices and lighter-skinned male faces; darker-skinned females are the most misclassified group (Azcona et al., 2023, p. 19). Issues of access to the most modern technologies can therefore reinforce the power relations that characterize many forms of violence against women.

The development and accessibility of new technologies also have positive effects:

First, digital technologies are also used to provide services for survivors of trauma. While such interventions could be criticized for being faceless and distant, for some they provide an accessible means of support that is not dependent on childcare and work commitments.

Second, technological violence has created a fourth wave of feminism worldwide. Digital technologies also provide opportunities for social activism, resistance, and recovery. The digital environment allows for new spatial forms and enables geographically distant and diverse communities to connect. It allows the emergence of communities based on shared interests and experiences, allowing not only the expression of experiences and injustices but also the chance to come together in a common struggle against different forms of violence. Global campaigns, including #metoo, #timesup, and #Delhibraveheart; and viral survivor statements such as “All are welcome” and “The list” are prime examples. Similarly, crowdfunded justice campaigns for survivors of violence against women have demonstrated the potential of the digital environment to democratize access to voice and resist exclusion. Crowdfunded justice campaigns have emerged as powerful tools for survivors of violence against women, leveraging the digital environment to democratize access to support and amplify marginalized voices. By utilizing online platforms, these campaigns enable survivors to share their stories, mobilize resources, and foster community solidarity, effectively challenging systemic exclusion. Digital activism is thriving and, according to some, is an integral part of the fourth wave of feminism, building solidarity across national divides (Jain, 2020). However, as Jain also warns, “cyberfeminism cannot be seen as a panacea for the universal demand for gender equality” (2020), as digital inequalities “create a disintegration of the idea of a ‘universal’ cyber feminist movement.” This highlights the need for online GV activism to be closely linked to resistance movements on the ground to make it accessible to women and girls who lack digital access (Barter & Koulu, 2021).

In summary, technological violence against women is a common phenomenon in the world in the third decade of the 21st century. It is particularly strong against women and children who do not have basic computer literacy, access to the internet, or even a simple smartphone. IT knowledge and education, social status, and the level of development of the state and society are important factors here. However, there is also a positive aspect to techno-cognitive progress, which has given rise to a fourth wave of feminism known as cyberfeminism. This emerging wave, together with legal institutions and public education, will help to prevent technological violence against women. To this goal, the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse was established (UN Women, 2023c).

Case Study

The Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse (Global Partnership) will bring together countries, international organizations, civil society, and the private sector to better prioritize, understand, prevent, and address the growing scourge of technology-facilitated gender violence. The Global Partnership is also an action coalition as part of the Denmark-led Technology for Democracy initiative. It will address gender-based online harassment and abuse in the long term, with an initial mission to deliver concrete results by the end of 2022 (Crockett & Vogelstein, 2022).

The Global Partnership will focus its work on three strategic objectives:

Develop and advance shared principles. Partners will develop a collection/ compendium of international best practices and principles that situate certain forms of gender-based online harassment and abuse as a type of intersectional gender discrimination, as a threat to democratic values—particularly in the context of gendered disinformation in elections—and, where applicable, as a violation or abuse of human rights with reference to both international and regional instruments. This includes emphasizing the need for greater accountability for perpetrators and framing the experience of gender-based online harassment and abuse as an impediment to individuals’ ability to exercise their right to freedom of expression, enjoy their rights related to privacy, and fully and equally participate in civic and political life.

Increase targeted programming and resources. Together, partners will focus resources on preventing and responding to gender-based online harassment and abuse, including programs that provide training and support to civil-society organizations, journalists, and politically active women on best practices to document and respond to technology-facilitated gender violence.

Expand reliable, comparable data and access to it. Partners will improve the regular collection of comparable data (at the national, regional, and global levels) on gender-based online harassment and abuse and its effects by governments, international organizations, technology platforms, and non-governmental organizations. They will also pilot and evaluate innovative, evidence-informed interventions. Such data should be collected in accordance with safety and ethical standards, and measure the prevalence, impact, and political and economic costs of gender-based online harassment and abuse, particularly at the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, age, disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity. The Global Partnership will also invest in building a rigorous evidence base to enhance understanding of risk and protective factors associated with experiencing and perpetrating gender-based online harassment and abuse.

As members of the Global Partnership, countries share several goals and expectations. By joining the Partnership, partners commit to:

- Prioritize the problem of gender-based online harassment and abuse and act in coordination with others to fulfill the Partnership’s three strategic objectives

- Devote the necessary time and staffing to make meaningful progress in achieving those objectives in 2022

- Advance activities within their own countries to prioritize and address gender-based online harassment and abuse, and collaborate with non-members to help advance the Partnership

- Refrain from and oppose the spread of gendered disinformation or any other form of gender-based online harassment and abuse by any state

Membership. The United States, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Australia, and the Republic of Korea formed the initial set of member countries in the Global Partnership (US Department of State, 2022). Some changes have occurred since then (see “Learning Activity: Understanding the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse”).

Learning Activity:

Understanding the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse

Objective: Students will examine the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse and analyze its strategic objectives. They will identify current and former member states, explain when and why some states are no longer members, and identify organizations with similar objectives.

- Visit the following White House archived document (of the Biden Administration): Launching the Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse | GPC | The White House

- In groups, discuss the purpose of the organization and its three start-up strategies.

- Make suggestions on how the strategies can be detailed by analyzing each strategic objective into tasks, objectives, time periods, and implementers.

- Answer the following questions:

- What is your understanding of the definition of technological violence? Why is it a dangerous phenomenon? Why is it important to recognize it?

- Which gender is most likely to engage in technological violence?

- Identify and discuss the consequences of technological violence, especially the impacts on victims.

- What prevention and response measures need to be taken to prevent technological crimes against women and their impact on victims or survivors?

- Now, visit the Policy Paper (2025) by the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office at The Global Partnership for Action on Gender-Based Online Harassment and Abuse calls for gender to be an integral part of the AI Action Summit – GOV.UK and examine the list of member countries. Do some research to answer the following questions:

- Which countries are no longer members of the Partnership? Have other countries become members?

- Is the Partnership still a viable organization? If so, what actions or initiatives is it engaged in?

- What, if any, similar entities are extant? Are they effective? What resources might be needed?

Types of Gender Violence Promoted by Technology

Technology-facilitated GV occurs across a range of relationships. Technology-facilitated GV is informed by the connection or relationship between the victim/survivor and the perpetrator. Lenhart et al. (2016) identified 10 types of harassment, including physical threats, name-calling, impersonation, spreading rumors, and encouraging others to harass a target (as cited in Marwick, 2021).

- Cyberstalking: Persistent and unwanted surveillance, harassment, or intimidation through electronic means such as emails, social media, or messaging apps.

- Cyberbullying: One form of cyber violence which has been well-studied and defined in detail by the EU institutions. It is understood as a form of cyber harassment most commonly affecting minors, regardless of their gender. It consists of repeated aggressive online behavior with the objective of frightening and undermining someone’s self-esteem or reputation, which sometimes pushes vulnerable individuals to depression and suicide. The European Parliament defined cyberbullying in a 2016 study as the “repeated verbal or psychological harassment carried out by an individual or group against others” (Van Der Wilk, 2018).

- Cyber Harassment:

- Trolling (online harassment). Verbal abuse, threats, or derogatory comments directed at individuals based on their gender, perceived gender identity, or sexual orientation; often occur in online forums, social media platforms, or gaming communities.

- Cyberbullying consists of repeated behavior using textual or graphical content with the aim of frightening and undermining someone’s self-esteem or reputation.

- Threats of violence, including rape threats, death threats, etc., directed at the victim and/or their offspring and relatives; or incitement to physical violence.

- Unsolicited receiving of sexually explicit materials.

- Mobbing refers to the act of choosing and targeting someone to bully or harass through a hostile mob deployment, sometimes including hundreds or thousands of people (Van Der Wilk, 2018).

- Online Disinformation: Spreading false or misleading information about individuals or groups based on their gender, perceived gender identity, or sexual orientation, often with the intent to incite hatred, discrimination, or violence.

- Online Sexual Exploitation: Coercing, manipulating, or deceiving individuals into engaging in sexual activities online, which may include sextortion, grooming, or luring through social media.

- Revenge Porn: Non-consensual distribution of intimate or sexual images or videos, often to shame, humiliate, or exert control over the victim.

- Doxxing (revealing personal information): Publishing private or identifying information about individuals online without their consent, leading to harassment, stalking, or real-world consequences.

- Tech-Facilitated Domestic Abuse: Abusers using technology to monitor, control, or manipulate their partners, such as through spyware, GPS tracking devices, or controlling access to digital devices and accounts.

- Sexist hate speech: Sexist hate speech is defined as expressions that spread, incite, promote or justify hatred based on sex:

- Posting and sharing violent content consists of portraying women as sexual objects or targets of violence

- Use of sexist and insulting comments, abusing women for expressing their views and for turning away sexual advances

- Pushing women to commit suicide

- Hate speech has proliferated online, with white-supremacist, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, anti-LGBTQIA+, and women-hating groups finding spaces to gather and promote their discriminatory beliefs

The term “hate speech online against women” encompasses different types of cyber violence, such as cyber harassment, cyberstalking, non-consensual image abuse, and also the specific term “sexist hate speech.” There is, however, no commonly accepted terminology for these relatively new forms of violence against women.

Direct Violence

Some forms of cyber violence against women have a direct impact on their immediate physical safety:

- Trafficking of women using technological means such as recruitment, luring women into prostitution, and sharing stolen graphical content to advertise for prostitution

- Sexualized extortion, also called sextortion and identity theft resulting in physical abuse

- Online grooming consists of setting up an online abusive relationship with a child, to bring the child into sexual abuse or child-trafficking situations. The term “grooming” is criticized by victims, as it covers the child sexual abuse dimension of the act

- In real-world attacks is defined as cyber violence having repercussions in “real life” (Van Der Wilk, 2018)

Threats

In the context of online behavior, “threats” refers to any communication or action that expresses an intention to cause harm, fear, or intimidation towards an individual or group. Threats can manifest in various forms and can have serious consequences for the victims. Threats in the digital realm can take many forms, including:

- Direct Threats: Explicit statements or messages that communicate a clear intention to cause harm, such as physical violence, property damage, or emotional distress

- Implied Threats: Communications or behaviors that suggest a potential for harm without explicitly stating it, such as menacing gestures, veiled language, or symbolic actions

- Online Threats: Threats communicated through digital channels, including email, social media, messaging apps, online forums, or gaming platforms

- Cyber Threats: Threats that involve the use of technology or hacking tools to inflict harm, such as cyberbullying, hacking, doxing, or spreading malware

Learning Activity:

Media Literacy

Objective: Students will analyze how online radicalization fosters the recruitment of young people into misogynistic culture. They will develop the ability to critically evaluate online content aimed at perpetuating sexist messaging and identify the strategies used to spread such harmful ideologies, which will help them develop critical media literacy skills.

- Choose two “news” articles about a topic likely informed by sexism, but do not choose mainstream print or online newspapers such as The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, etc. Choose sources that you are unfamiliar with. Suggested topics: trans girls/women in sports, reproductive healthcare, or wage gaps. Choose sources from various viewpoints or political affiliations.

- Next, evaluate the media source laterally. Check to see if this source has any professional affiliations. Do national or international professional organizations sponsor it? Are these organizations considered credible? Perform a quick Google Search for the media source. Do you notice any whistle-blowing about this media source? Can you fact-check the information listed in the article with peer-reviewed sources and mainstream news publications? Does the article contain hate speech or outdated language to refer to race, gender, or sexuality?

- Share the findings with the class, paying close attention to how easy it can be to misread a media source’s intentions.

Forms of Cyberviolence

The European Commission explicitly includes “cyberviolence and harassment using new technologies” in its definition of gender violence (European Commission, 2018).

The International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) is leading the Technology-facilitated gender based violence: What is it, and how do we measure it? project in partnership with the World Bank and has developed a conceptual framework that allows us to visualize the scope of cyber violence and hate speech at a glance (Hinson et al., 2018).

Technological harassers and their victims are connected. The relations are personal, interpersonal, and institutional. Technology-facilitated violence depends on the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator. These relationships may be personal or impersonal. Alternatively, the relationship may be institutional, where public figures or state institutions engage in GV through the use of technology to implement an ideological agenda or enforce legislation (Hinson et al., 2018). Motivation is very important: the motivation of an offender is the emotional, psychological, functional, or ideological factor(s) that drives the offender’s behavior. Motivation may be political or ideological in nature or driven by revenge. Motivation stems from the offender’s intention or determination to harm someone. Similar to motivation, intent varies according to the type of behavior, and can include psychological or physical harm, enforcement of gender norms, or rape (Hinson et al., 2018).

Motivation and intention are determined by technological access—the internet. It reveals the behavior of a technological abuser. And this is the third component. “Behavior” refers to the perpetrator’s actions or strategies, which can include stalking, defamation, bullying, sexual harassment, exploitation, and hate speech. Each behavior may be repeated with varying frequency and may be perpetrated through one or more forms of technology (modalities), such as social networking sites or entertainment platforms. Criminals use a variety of technology-based tactics, such as hacking and threat transmission, to carry out specific technology-based behaviors (Hinson et al., 2018).

Impact on Victims

Technology-driven violence on victims can include significant harm to their physical and mental health, social status and economic opportunities; and, in some cases, have led to death. The impact is divided into five categories:

- Psychological (e.g., shame, depression, or fear)

- Physical (e.g., self-harm, assault, or arrest)

- Functional (e.g., changing a route or taking down a profile)

- Economic (e.g., extortion or loss of income-generating or educational opportunities)

- Social (e.g., excluded by family, friends, or coworkers) (Hinson et al., 2018)

However, different types of technological violence will have different impacts or consequences for the victims; for example, in the case of threats.

Emotional distress: threats can cause significant psychological harm, leading to fear, anxiety, depression, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Physical harm: In some cases, threats may escalate to physical violence or harm, posing a direct threat to the safety and well-being of the victims.

Social isolation: Victims of threats may experience social isolation, ostracism, or exclusion from their communities or social networks.

Legal and financial consequences: Depending on the severity and nature of the threats, victims may have to deal with legal issues; including criminal charges, restraining orders, or civil lawsuits. Threats can also result in financial losses, such as legal fees, medical expenses, or property damage.

Measures Against Violence

There are a variety of help-seeking or coping behaviors that a victim/survivor can take that include, but are not limited to, reporting their experience to the police, seeking health, counseling, or legal aid services, and seeking help from their social networks (Hinson et al., 2018).

In addition to the general measures to prevent and protect against technological violence, it is necessary to analyze individual cases of technological violence and to implement the necessary measures to deal with them. As an example, the case of threats can be analyzed.

Safety Planning: Victims of threats should prioritize their safety by seeking support from trusted friends, family members, or authorities; and developing a safety plan to mitigate the risk of harm.

Reporting: Victims should report threats to the appropriate authorities, such as law enforcement agencies, school administrators, or online platform moderators, to ensure proper investigation and intervention.

Legal Action: Victims may pursue legal action against perpetrators of threats through civil or criminal proceedings, including obtaining restraining orders, filing harassment charges, or seeking damages for emotional distress.

Prevention Education: Educating individuals about the consequences of making threats and promoting empathy, conflict resolution skills, and positive communication techniques can help prevent threats and promote a culture of respect and tolerance.

A global study by the “Economist Intelligence Unit” found that 38% of women have personally experienced online violence, and 85% of women who spend time online have witnessed digital violence against other women. A Pew Research Center survey of US adults in September 2017 found that 41% of Americans had personally experienced some form of online harassment in at least one of the six key ways that were measured. Gender also plays a role in the types of harassment people are likely to encounter online. Overall, men are somewhat more likely than women to say they have experienced any form of harassment online (43% vs. 38%), but similar shares of men and women have faced more severe forms of this kind of abuse. There are also differences across individual types of online harassment in the types of negative incidents they have personally encountered online. Some 35% of men say they have been called an offensive name versus 26% of women, and being physically threatened online is more common occurrence for men rather than women (16% vs. 11%). Women, on the other hand, are more likely than men to report having been sexually harassed online (16% vs. 5%) or stalked (13% vs. 9%). Young women are particularly likely to have experienced sexual harassment online. Fully 33% of women under 35 say they have been sexually harassed online, while 11% of men under 35 say the same. Lesbian, gay, or bisexual adults are particularly likely to face harassment online. Roughly seven-in-ten have encountered any harassment online and fully 51% have been targeted for more severe forms of online abuse. By comparison, about four-in-ten straight adults have endured any form of harassment online, and only 23% have undergone any of the more severe behaviors (Vogels, 2021).

Digital violence can increase offline forms of violence—including sexual harassment, stalking, intimate partner violence, trafficking, and sexual exploitation—through the use of digital tools like mobile phones, GPS, and tracking devices. For instance, traffickers often use technology to profile, recruit, control, and exploit their victims (UN Women, 2025).

In summary, there are various forms of technological violence, including online harassment, cyber-violence, and others. It is important to recognize violence and to take action to prevent its spread.

Resisting Digital Violence

What more needs to happen to eliminate violence in the digital world? Here are some suggestions:

Enhance cooperation between governments, the technology sector, women’s rights organizations, and civil society to strengthen policies.

Address data gaps to increase understanding about the causes of violence and the profiles of perpetrators and to inform prevention and response efforts.

Develop and implement laws and regulations with the participation of survivors and women’s organizations.

Develop standards of accountability for internet intermediaries and technology sector to enhance transparency and accountability on digital violence and the use of data.

Integrate digital citizenship and ethical use of digital tools into school curricula to foster positive social norms online and off, sensitize young people—especially young men and boys—caregivers, and educators to ethical and responsible online behavior.

Strengthen collective action of public and private sector entities and women’s rights organizations.

Empower women and girls to participate and lead in the technology sector to inform the design and use of safe digital tools and spaces free of violence.

Ensure that public and private sector entities prioritize the prevention and elimination of digital violence, through human rights-based design approaches and adequate investments.

Summary

We have seen that new information technologies can be used in negative ways against LGBTQIA+ people, women, and children, at the interpersonal and structural levels. Digital and online violence include behaviors like cyber bullying and harassment, online disinformation, doxxing, and sexist hate speech. Digital and online violence can allow and aggravate offline violence as well, from interpersonal violence to trafficking. Impacts on victims can be serious and include psychological, physical, economic, and social harms.

We have also seen that measures exist to resist and reduce these kinds of violence; from individual safety planning, reporting, and legal actions to cooperative national and international efforts to implement laws, accumulate relevant data, and strengthen collective public-private sector collaborations. Awareness, education, and action are needed to increase the safe and unhindered use of new technologies by women, girls, and LGBTQIA+ people.

Review Questions

Questions for Reflection

- How does exposure to the manosphere (web content that promotes misogyny) impact the beliefs, behaviors, and development of young men? What role does social media play in this process? How do the experiences of LGBTQIA+ individuals differ within the manosphere compared to women? What unique forms of discrimination do they face?

- Women and girls are often targets of sexual, gendered, and sexist violence online. How does the patriarchy reinforce women’s oppression in the media? How does this impact how women and girls interact more broadly with online platforms and media?

- What are some strategies whereby individuals and groups can resist technological violence against girls, women, and LGBTQIA+ people? What resources are available? Which are still needed? Are there any ways you can help, as an individual or part of a group?

References

Azcona, G., Bhatt, A., Fortuny Fillo, G., Min, Y., Page, H., & You, S. (2023). Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The gender snapshot 2023. UN Women/United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/09/progress-on-the-sustainable-development-goals-the-gender-snapshot-2023

Barter, C., & Koulu, S. (2021). Digital technologies and gender-based violence—mechanisms for oppression, activism and recovery. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 5(3), 367-375. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868021X16315286472556

Begum, R. (2021, June 28). Egypt persecutes TikTok women while men get impunity for sexual violence. The New Arab. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/28/egypt-persecutes-tiktok-women-while-men-get-impunity-sexual-violence

Crockett, C., & Vogelstein, R. (2022, March 18). Launching the global partnership for action on gender-based online harassment and abuse. White House Gender Policy Council. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/gpc/briefing-room/2022/03/18/launching-the-global-partnership-for-action-on-gender-based-online-harassment-and-abuse/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Duhaime-Ross, A. (2015, September 24). The UN says we need to ‘wake up’ and fight violence against women and girls online. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2015/9/24/9392067/united-nations-cyber-violence-against-women-report-tech?utm_source=chatgpt.com

European Commission. (2018). What is gender-based violence? https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/gender-equality/gender-based-violence/what-gender-based-violence_en

Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. (2025, February 10). The global partnership for action on gender-based online harassment and abuse calls for gender to be an integral part of the AI action summit [Policy paper]. Gov.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-global-partnership-for-action-on-gender-based-online-harassment-and-abuse-calls-for-gender-to-be-an-integral-part-of-the-ai-action-summit

Hicks, J. (2021). Global evidence on the prevalence and impact of online gender-based violence (OGBV) [Report]. The Institute of Development Studies and Partner Organisations. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12413/16983

Hinson, L., Mueller, J., O’Brien-Milne, L., & Wandera, N. (2018). Technology-facilitated GBV: What is it, and how do we measure it? International Center for Research on Women. https://www.icrw.org/publications/technology-facilitated-gender-based-violence-what-is-it-and-how-do-we-measure-it/

International Telecommunication Union. (2022a, September 16). Internet surge slows, leaving 2.7 billion people offline in 2022. https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/Pages/PR-2022-09-16-Internet-surge-slows.aspx

International Telecommunication Union. (2022b, November 30). Internet more affordable and widespread, but world’s poorest still shut off from online opportunities [Press release]. https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/Pages/PR-2022-11-30-Facts-Figures-2022.aspx

International Telecommunication Union. (2023a, November). Bridging the gender divide. https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/backgrounders/Pages/bridging-the-gender-divide.aspx

International Telecommunication Union. (2023b, November 27). New global connectivity data shows growth, but divides persist. https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/Pages/PR-2023-11-27-facts-and-figures-measuring-digital-development.aspx

Jain, S. (2020, July). The rising fourth wave: Feminist activism and digital platforms in India. ORF Issue Brief No. 384. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/public/uploads/posts/pdf/20230524183029.pdf

Marwick, A. (2021). Morally motivated networked harassment as normative reinforcement. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211021378

UN Women. (2023a). Technology-facilitated violence against women. Report of the meeting of the Expert Group, 15-16 November 2022, New York, USA. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/03/expert-group-meeting-report-technology-facilitated-violence-against-women

UN Women. (2023b, April). The state of evidence and data collection on technology-facilitated violence against women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/04/brief-the-state-of-evidence-and-data-collection-on-technology-facilitated-violence-against-women

UN Women. (2023c, November 13). Creating safe digital spaces free of trolls, doxing, and hate speech. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/explainer/2023/11/creating-safe-digital-spaces-free-of-trolls-doxing-and-hate-speech?utm_source=chatgpt.com

UN Women. (2025, February 10). FAQs: Digital abuse, trolling, stalking, doxing and other forms of violence against women in the digital age. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/faqs/tech-facilitated-gender-based-violence

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2022, July). Using the power of technology to help victims of human trafficking. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/frontpage/2022/July/using-the-power-of-technology-to-help-victims-of-human-trafficking.html

United States Department of State. (2022, March 16). 2022 Roadmap for the global partnership for action on gender-based online harassment and abuse. Office of the Spokesperson. https://2021-2025.state.gov/2022-roadmap-for-the-global-partnership-for-action-on-gender-based-online-harassment-and-abuse/ [Archived content]

Van Der Wilk, A. (2018, August). Cyber violence and hate speech online against women. Women’s rights & gender equality study for the FEMM Committee. Policy Department for Citizen’s Rights and Constitutional Affairs. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/604979/IPOL_STU(2018)604979_EN.pdf

Vogels, E. A. (2021, January 13). The state of online harassment. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Further Learning

Equimundo. (n.d.). Gender equality needs men, and men need gender equality. https://www.equimundo.org/

UN Women. (2025, February 10). FAQs: Digital abuse, trolling, stalking, and other forms of technology-facilitated violence against women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/faqs/tech-facilitated-gender-based-violence

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2024, December 16). “Digital rights are human rights:” Women activists fight cybersexism. https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2024/12/digital-rights-are-human-rights-women-activists-fight-cybersexism

Media Attributions

- marija-zaric-fS1N3cxljac-unsplash © Marija Zaric is licensed under an Unsplash license

- young-woman-1064659 © Concord90 is licensed under a Pixabay license