Gender Violence and Religion

Shannon Garvin

Abstract

As both an inherited and constructed set of beliefs to understand the world, religion presents unique challenges when addressing the issue of violence. Patriarchy and religion meld to oppress women, children, LGBTQIA+ people, and other minoritized groups. While people want to believe in the divine to find comfort and meaning in life, they also attempt to control it to exert their own human power. Religion is used both to justify and to resist systems of oppression.

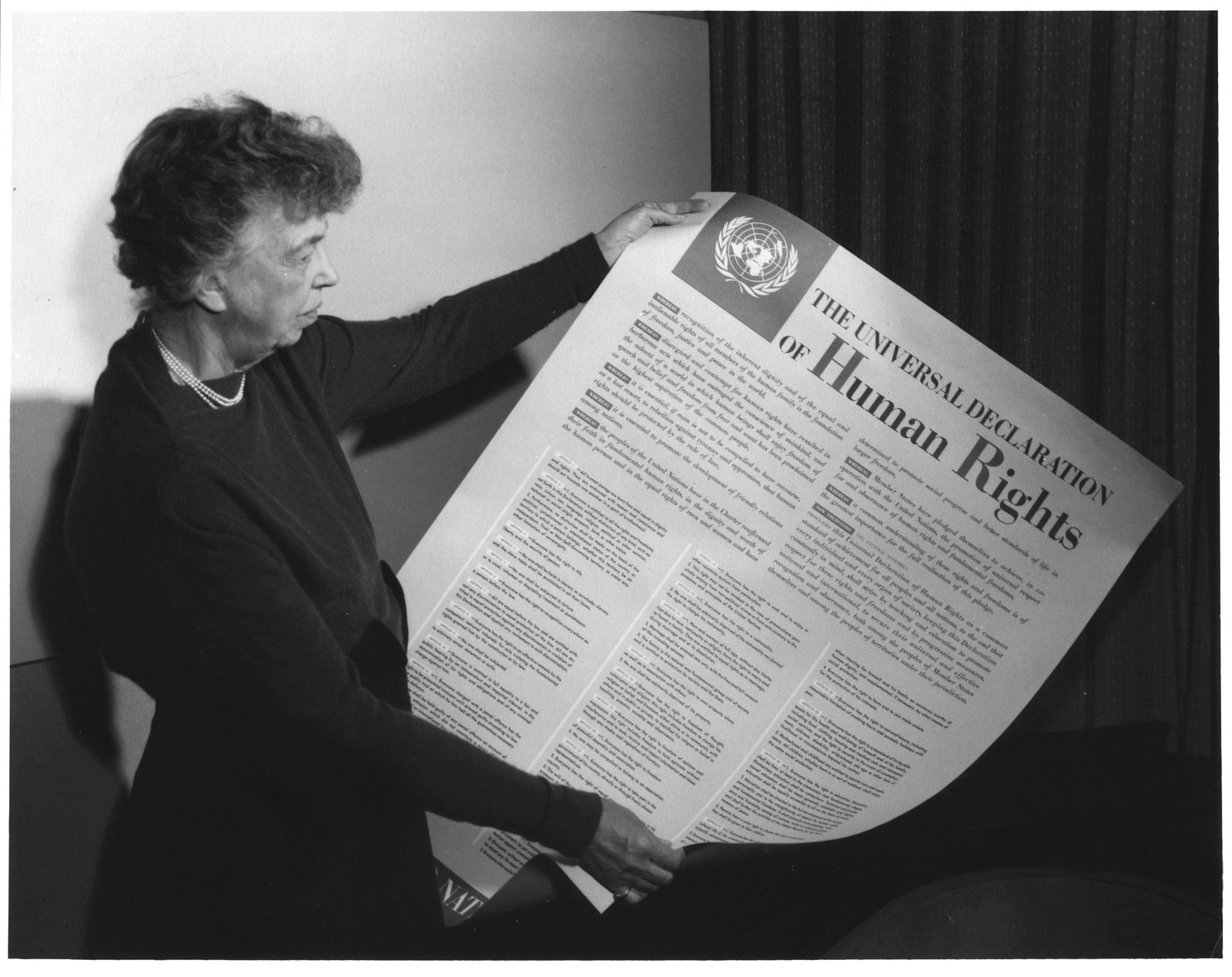

This chapter explores the ways in which we can resist violence against women and other minorities by reaching deeper into religious beliefs to explore the shared core of the world’s religions which honor humanity and call for compassion and service to others. The wide religious backgrounds of Nobel Peace Prize winners and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights also offer glimpses of ways we can tap our common humanity and shared core religious beliefs to do good and resist violence.

Learning Outcomes

- Students will describe several ways religions both justify oppression against minoritized groups and enable resistance through common meaning-making

- Students will analyze the relationships between shared core beliefs in religions and in human rights advocates and initiatives

- Students will explain the connections between current extreme religious movements and power grabs by men within government and corporations

More than anything else, I said, I want to be the last girl in the world with a story like mine.

Nadia Murad, UN Address, September 16, 2016

What Is Religion? Why Does It Matter?

A discussion on resisting religious violence against women may begin by asking whether there is a point to religion in the first place. Does religion have value today? The young people of the US and parts of Western Europe can move between religions, picking and choosing which tidbits they love or hate. However, this has not been the experience of the vast majority of the people in the world. Mercy Oduyoye reminds us that we are born into the religion of our family or ethnic group (Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians , n.d.). Many who wish to leave a religion must also leave their family, friends, support system, and community; and in some countries, it is illegal for women or children to change their religion. In several countries, like the Sudan, children must become life-long adherents to the religion of their father even if they never live with him (Ibraheem & Bach, 2022).

Religion is not easily defined; rather, it can be described in terms of both its esoteric beliefs and its everyday applications. In the end, religion is a set of beliefs and practices which helps people make sense and meaning of the world (Pew Research Center, 2022). Religions can be large-scale and tightly organized or loosely organized; they can be small and local; they can even be individual. Even people who are non-religious engage in acts of meaning-making, and religion affects their lives because of its influence as a social institution ordering relationships, influencing policy and practice, and pervading cultural norms. Whether we actively engage religion or try to reject it, we are all surrounded by the effects of a world full of other people also engaged in systems of meaning-making.

Religion, in and of itself, is neither good nor bad. While for many people, it offers personal comfort and encouragement to do good in the world and work toward justice; it is also used to gain power and oppress others (Pew Research Center, 2022). Prolonged dominance over others requires the use of violence and/or the threat of violence. Religions often justify and promote violence, especially against women, LGBTQIA+ people, and other minoritized populations.

Across the world and throughout history, people have spoken or written about their experiences with the divine or the spiritual essence of themselves. Whether it was Abraham called by God out of Haran to a land of his own, Jesus teaching about living a life of love toward others, Muhammed dictating to his wives his experiences with Allah, Tawûsî Melek watching over the Yazidi people, or local artists rendering images of the Hindu God in its endless manifestations; religion connects the divine residing outside us with the divine voice/presence/longing inside each of us. The Quakers call this the light of Christ. Buddhists reject a definition, but seek to move this essence toward Nirvana. Asian cultures with Confucianist history integrate this philosophy into their functioning worldview so much that even Chinese atheism functions as a full-blown religion, with the Chinese Party as the deity and the Chairman as its representative on earth.

Since religion is such an intrinsic part of the human journey, how can we engage it in our personal lives and on behalf of others? These are the true questions of religion worth considering, regardless of which religion we claim. In society, religion can reinforce or promote an inequitable status quo. Religion frequently abdicates personal responsibility toward others by justifying oppression or violence as Divine will (Kippenberg, 2011; Mikhail, 2018). As a means of making sense of the world, religion can easily play either hero or villain, depending on people’s motives: it can both justify violence, and call violence into question (Le Roux, 2017). Violence against women, children, people with disabilities, and LGBTQIA+ people can be enacted through all social institutions, from law and government to education, healthcare, and the economy; these sites of violence are often rooted in religion and personal systems of meaning-making (Türkkan & Odacı, 2024). For example, in the United States, the current spate of anti-transgender national laws and policies is closely connected to conservative Christian beliefs about gender binaries. At the same time, other Christians, driven by their religious convictions, are working passionately to support and protect transgender people.

Why Does Religion Turn Violent?

When they begin, religions are vibrant and alive. They spread among people as fast-moving ideas to explain the world. Women are often at the forefront of religious movements in their early stages, but as they gain traction and become formally organized, men move to the front and women are pushed to the back (Garvin, 2022). Because patriarchy has limited women’s religious leadership, most religious texts and records have been written by men and reflect men’s experiences of the world, despite claiming to be authoritative for all experiences (Andaya, 2006). When women, children, and other minorities are not active participants in the codification of religions, their lives and experiences do not inform the meaning-making process; the experiences of the dominant group become normative, and these norms perpetuate dominance (Garvin, 2021).

Because violence and threats of violence are necessary pieces of dominance within patriarchy, gendered religious violence becomes a central feature (Carter, 2014; Sotoudeh, 2023). While established religions tend to blame and vilify women as “unclean” from menstruation (Stange et al., 2011), require them to be “submissive” to men for a host of reasons, and view physical or sexual differences as deformities; they also highlight the power struggle in every religion to understand the differences between the gendered human experience with physical bodies and an ungendered divine being or spirit. The urge to label others as inferior or to deny them equal human rights is a common human reaction to difference: religion merely claims a divine justification for it.

Just as languages do not share exact conceptual meanings (in translation), neither do religious systems of belief. Much of the inter-religious conflict we see today is a result of this. For instance, Hinduism does not differentiate between philosophy and religion; this gives great latitude in reimaging a deity in endless manifestations. On top of all this, ultraconservative or fundamentalist movements in a religious system always lead to more repressive systems of gender violence, as we see today in the rise of white Christian nationalism (Gross, 2024), the influence of hyper-conservative forms of Islam like Wahhabism (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2022), and the genocide of Gazans by a Zionist Israeli government (Shaheed, 2020).

Religious Justifications for Violence Against Women

Systemic oppression and abuse of women is commonly excused or required by religious teachings (Cooke, 2019; Murad & Krajeski, 2017; Nason-Clark, 1996; Türkkan & Odacı, 2024), as a way to safeguard male power and dominance. Religious violence takes many forms: honor killings, acid attacks, rape, forced prostitution, sex trade, assault, sexual assault, hunger, neglect, female genital mutilation/cutting, shaving hair, kidnappings, forced marriage, denying sexual literacy, purity culture, queer-bashing, arrest, torture, execution, and femicide (Carter, 2014; Garvin, 2021; UN Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022).

Some religious doctrines allow men to maintain dominance in the name of and under the command of their deity (Le Roux, 2017; Türkkan & Odacı, 2024). These systems not only perpetuate conditions where women must cook, clean, and bear children—which is dismissed as unvalued labor (Despeux & Kohn, 2003)—they may also encourage intentional abuse (Ajayi et al., 2022).

Blame and Shame, Obedience and Coercion

In addition to the physical violence against the bodies in which women and other gender minorities live, they also face mental, social, emotional, and economic violence through religious belief and practice. Such beliefs may deny them access to healthcare and education. Strict adherence to these beliefs mean women may remain socially isolated in their homes, and be judged solely on the status of their virginity.

Some religions dictate that women cannot enter religious leadership or speak to systems of religious governance. When men retain all of the positions of teaching and leadership within a religion, women do not know the parts of the sacred texts which tell men to treat all people with kindness and compassion (Zoepf, 2016). They do not know that they, too, are considered valuable as an individual.

Virginity and Male Honor

In some societies, the condition of a woman’s virginity and whether she is “pure” enough to bear children for a man is centralized in religion to the extent that the “honor” of her male family members rests on her uterus (Chesler & McGovern, 2015; Zoepf, 2016). Fathers, brothers, uncles, and other male relatives plot and kill (Kippenberg, 2011) thousands of women a year in “honor killings,” while local laws protect this violence (Nadeau & Mortensen, 2024; Yousafzai & Lamb, 2013).

Honor killings and acid attacks, or “burnings” in Pakistan, exemplify the trauma inflicted on women when their bodies become the living vessels of male honor. Lama Abu-Odeh argues that the very idea of masculinity in Arab countries is bound up with the defense of female relatives’ chastity (Zoepf, 2016).

Women Are No One’s Honor / زن ناموس هیچکس نیست

Sajjad Kalanaky

In Iran, femicide or honor killings (ghatle namoosi), “the misogynous killing of women by men” (Radford & Russell, 1992) are often perpetrated by male relatives for the sake of preserving the family’s honor.

Most femicide victims are under age 50, and at least one was just nine years old (Stop Femicide Iran, 2024). Husbands or ex-husbands are the main perpetrators; they may stab, strangle, suffocate, shoot, behead, or set their victim on fire.

Iranian law allows and even encourages femicides. Article 630 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code states: “Whenever a man sees his wife committing adultery with a man and knows that the wife has consented to it, he can kill both of them.” Therefore, “this kind of ‘honor killing’ is not punishable” (Farhadi & Janjevic, 2024).

Honor killings also affect LGBTQIA+ people. One of the most horrific queer honor killings was the beheading of Ali Fazeli Monfared in 2021 by his male relatives after he was outed as gay (Pakzad, 2021).

Stop Femicide Iran (n.d.) fights femicide with the three-pronged approach of “documentation, education, and empowerment” and Stop Honor Killings (n.d.) endeavors to give a “voice to the victims of honor killings,” encapsulated by their motto:

“Women are no one’s property. No one is defined as another person’s honor.”

“زن ناموس هیچکس نیست. هیچکس ناموس هیچکس نیست.”

While Christians may question these actions, generations of “Purity Culture” in Western Christianity separate women from healthcare and saddle them with the responsibility for any “impure” thoughts any man or boy might have about her body. Many Christian women live lives of guilt and warped sexuality, where they don’t understand how to access medical care after a miscarriage, or are condemned and shunned for reporting abuse (Flanagan, 2024).

Females are also the victims of child marriages. Across parts of the Middle East and Africa, a young girl is not even required to be present at her own wedding, but finds out when her family takes her to another house and abandons her there to a lifetime of rape and childbearing at the hand of whoever paid her parents her dowry (Ajayi et al., 2022).

Historically, wars have been waged over resources and religious beliefs. As a result, it is important to maintain a steady supply of young men to fight those wars, and only women can bear those men. So, men use and abuse women in the name of religion to fight wars and expand their influence and power (Gbowee & Mithers, 2011) even though the Bible, like the Quran, extols not the virtues of power, but those of community and care for the poor.

Queer people who do not fall within the binaries of male and female are considered ultimately destructive to the power structures that safeguard the patriarchal systems that oppress women, children, and minorities so that a few men can lead lives of greed, power, and leisure. Same-sex couples create homes without the requisite binary hierarchy that supports the continuation of social oppression. Two lesbian women are not being ruled by a man or two gay men are not engaged in oppressing women. Members of the trans population expose the reality that men and women are not superior or inferior based on genitalia, but rather confirm that both women and men are equally smart and gifted in life.

Women from Eastern Europe and those from the United States to South America continue to face another form of sexual violence—lack of access to abortion and continued narrowing of reproductive rights (Human Rights Watch, 2005; Kasztelan, 2024). Countries with significant conservative Christian populations use religious beliefs to control women through limitation of reproductive freedoms. At this moment in the US, a key argument is when “personhood” begins. Many argue that a fertilized egg is a full human being with all of the rights of any other person.

The male leaders of Catholic and evangelical Protestant churches have declared loudly and emphatically that even when they cannot tell you anything about how female anatomy works (Marder, 2022), they say life begins at conception (Bricker, 2022), which is defined as the moment a sperm enters an egg and God adds a divine spark. Many religious people also refuse to accept gender diversity (Eske, 2023; Hattenstone, 2019).

The fight over “abortion rights” is less about sustaining life than it is about power and who controls the sexual life of women, viewed as temptresses in the legacy of Eve (Edwards, 2022; Milne, 1989). While the oldest battle in religious belief has been the power of women over reproduction and fertility—and how men live in fear because they do not hold that power—for those in Judaism and Christianity, it is a double indictment because the sexuality of woman also caused the demise of a perfectly created world made by God for man. So, the pushback is not just about bodily autonomy, but also resentment and religious blame for evil in the world. Resistance to sexual violence against Catholic, Protestant, and all women requires continuing to uphold the rights for each person to make medical decisions about their own bodies without religiously motivated civil laws.

Without knowledge of how their own body works or access to medical care for pregnancies, births, miscarriages, and infertility, women bear the religious irresponsibility of men within their own bodies, minds, heart, and souls.

Religious Violence in Conservative Movements

Today, conservative movements are expanding oppression as they peel back the democracies and freedoms of the Post-World War II era. While we can look at this as only a religious movement, we miss the point if we do not connect the religious actions to expansion of corporate empires under the guise of religion. Religion teaches people to comply; democracy teaches people to choose. Corporate big men have gained traction since 1980 by forming working relationships with religious leaders. Since January 2025, Americans have seen that the religious leaders were not really moving corporate leaders “toward God, but rather corporate leaders were manipulating religious leaders and groups to expand their power, influence, and profits.”

In a time where women are fighting for equal healthcare and wages, the “trad wife” influencers have distracted women away from equal rights. In Texas, maternal mortality rates have skyrocketed as doctors were prohibited from performing needed abortions. Transgender people are increasingly targeted by social stigma and withholding of essential medical care.

At a national level, Americans claim to want to support democracies and freedom around the world, but Republican presidents end healthcare funding for the world’s most vulnerable women, and 2025 has seen the brutal dismantling of the world’s largest refugee- and democracy-stabilizing work in the history of the world, as all USAID employees were abruptly fired.

The devastating changes wrought since January of 2025 have not proved that hatred against women, people of color, and LGBTQIA+ people is justified. Rather it has highlighted the hypocrisies of fundamentalists who claim to work on behalf of a divine being; but who, in truth, seek only to wield power over others.

Religious Violence and Anti-Democratic Politics

Since Republican candidate Ronald Reagan falsely claimed in 1980 that poor black women were scamming hard-working Americans out of their money, this lie has become the backbone of Republican fiscal policy to outrage and distract voters—while corporations and their stockholders consolidated nearly all the wealth in America. A group of conservative evangelical and Catholic religious leaders joined the Reagan campaign to rally churchgoers around the “offense” of women accessing abortions legally. Although they framed abortion as a religious issue, it has really been about power—a backlash against the legal rights women finally obtained in the 1970’s, from owning bank accounts to accessing healthcare without guardianship. Republicans today are the heirs of that backlash—stealing wealth and control from Americans under the guise of religious mandates.

Project 2025 is a result of two decades of research and planning on how to circumvent the checks and balances of our Constitutional system to institute White Christian Nationalism. Since Project 2025 comes out of a hyper-conservative religion and aims for a minority (white men) to control everyone else, its main target is the re-subjugation of women, children, LGBTQIA+ people, and other minorities; stripping them of freedoms, rights, and a voice in their life and future. For example, for over a decade, Leo Leonard has schemed to install Supreme Court judges (Kroll et al., 2023) to ensure the court does not use its constitutional power to control the overreach of the White House. Dark money and quiet backers like the Koch brothers have funded decades of legislative campaigns to elect weak politicians to enable control of Congress.

The chaos we see in in Washington, DC, today constitutes an organized assault on American democracy. Casualties include mass firings, gutting and eliminating of departments, cancellation of grants and funding, illegal deportations of immigrants and students; and orders illegally given and followed, ignoring courts and the law.

For all of this, the people behind these movements are eager to dismantle our democracy. Some may wish to think of this moment as the “dying gasp” of white male power, but the moment is more likely to catapult all of us into a dark future of fascism if we do not stand up and own our democracy, as Eleanor Roosevelt challenged us to do. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. reminded us that “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom” (King, 1967).

Religion, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Any religion, by itself, cannot solve the problem of human violence against others. History shows that individuals in any time and place can wield too much influence in a particular religion and quickly inspire mass violence. Charismatic men may pursue their own narcissistic ends by surrounding themselves with followers who will support them in exchange for furthering their own power-based agendas. Too often, these include oppression of women, LGBTQIA+ people, and ethnic minorities: for example, controlling people’s reproductive freedom of choice, ensuring white supremacy over people of color, and enforcing “normative” heterosexuality.

How do we provide tethers—safeguards—for religion? Not by limiting religion, but by coming together, taking the best wisdom from all our faiths, and combining them to ensure protections in which all people can realize their human potential. In this, government and religion enter a symbiotic relationship where legal freedom protects religious expression and religious freedom ensures one religion cannot gain political power over others.

In The Moral Basis of Democracy (1940), Eleanor Roosevelt explained how religion teaches us to care for each other in a society, but that society cannot confine itself to only one religion, or it does not experience true freedom. Each generation must choose for itself whether it will engage in the work of democracy for themselves and their children. The moral basis of democracy is born of religion, but it must offer freedom to all because the future of any society lies in whether it concerns itself with all members: “the common good.”

After the horrors of World War II, President Truman asked influential speaker and author First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to become the United States’ first representative to the United Nations. Her experience traveling the country listening to the women who filled the factories, combined with her shared dream with FDR of the UN as a place the world could come together and avoid the mistakes that followed the war, made her uniquely gifted to lead world leaders to agree on a Universal Declaration of Human Rights built on the best of the world’s religions, but not constrained by any one of them. She led the process of succinctly defining what it means to live without fear as a human being, in any nation, with any religion. In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the world’s nations (United Nations, n.d.).

Today, many countries look to the United Nations and pluralistic democracies (those in which power is distributed across groups) to support resistance to religious violence in their countries and establish their own democracies. The sudden fall of Afghanistan back to the Taliban reminds us that young democracies are fragile and support is needed to root democracy in people’s hearts and their systems of civil government, which both supports religion and protects its citizens from religious violence (Maizland, 2023; Shahalimi & Atwood, 2022). The UDHR remains the gold standard for the rights each person is entitled to enjoy in their own life regardless of their government, race, country, culture of origin, faith, gender, physical body, or any other human difference (Sotoudeh, 2023).

Resisting Religious Violence

The work of resisting religious violence happens at several levels: within ourselves, in our communities, in our countries, and across the world. Each of us is suited for exceptional engagement at one or more of these levels. How do we learn about each other, commit to resist violence, and create a more equitable world?

Question Religious Justifications for Violence

The following books and accounts offer insights into women’s struggles to reclaim the inherent worth of individuals promised at the heart of their religions, in spite of attempts to justify violence in the name of those religions.

Surviving God (Kim & Shaw, 2024) offers permission for an ungendered reading of the Bible as resistance against the shocking prevalence of sexual violence against women in conservative Christianity.

We Are Still Here (Shahalimi & Atwood, 2022) exposes the lived realities of Afghan women and highlights their resistance in the face of the extremist Taliban takeover.

Lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh (2023) describes the work of Iranians fighting mandatory hijab and death penalty in Women, Life, Freedom.

Businesswoman Mariam Ibraheem recounts death row and growing up in the refugee camps of Sudan under Sharia law in Shackled (Ibraheem & Bach, 2022).

Learn from Peace Advocates

The annual Nobel Peace Prize recognizes a person or group that has distinguished itself by breathing life into the hurting parts of a society or the world at large (The Nobel Prize, n.d.). Taking the time to learn about these award recipients will motivate you to resist violence.

Nadia Murad (NPP 2018) shared with the world her experiences in the sex trade and the attempted genocide of the Yazidi religious minority (Murad & Krajeski, 2017).

Shirin ʻIbādī (Ebadi) (NPP 2003), a sitting judge at the time of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, speaks out about how religious violence dismisses women from existence (ʻIbādī & Moaveni, 2006).

Being shot by the Taliban at age 15 did not stop Malala Yousafzai (NPP 2014) from advocating for girl’s education (Yousafzai & Lamb, 2013).

President Jimmy Carter (NPP 2002) continued to advocate for ending religious violence against women and recognizing our previously unseen prejudices even from his hospice bed (2014).

In 2003, social worker Leymah Gbowee (NPP 2011) led a non-violent movement of Christian and Muslim women (WIPNET) in Liberia, forcing its dictator to go into exile, restoring democracy, and enabling Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (NPP 2011) to become president in 2006 (Stiehm, 2006).

Kenyan scientist Wangari Muta Maathai (NPP 2004) organized resistance to religious tribal violence in 1977 by partnering with displaced women to plant trees and eventually creating the Green Belt Movement, an environmental-religious-peace-women’s rights movement (Maathai, 2007).

Challenge Yourself to Engage Against Religious Violence

Nobel Peace Prize winners and other notable brave women offer the following ideas for large and small ways you can engage with resistance to religious violence and support others in their efforts to do so:

- Value the stories of victims and survivors

- Create opportunities to make ungendered readings of religious texts

- Hold/host meaningful conversations with religious and civil leaders

- Identify and partner with informal religious leaders

- Provide access to social services for survivors

- Create platforms to gain the attention of international leaders with change-making resources and influence

- Embody kindness and sit with the broken-hearted

- Make time to read personal stories

- Provide money to travel to centers of violence to partner with and resource endangered populations

- Prioritize listening over assuming

- Find the courage to speak truth to power while doing so in a way that does not end a conversation

- Cultivate the desire to continue learning and growing yourself into new ways of thinking and understanding

- Find the sheer tenacity to believe in hope

- Name and integrate the conscious and unconscious influences of your own experiences and religious beliefs

Resisting religious violence requires recognizing, developing, and using all of these skills regardless of your culture, background, or own religious choices.

Organized Resistance Today

While we do our own personal work to resist gender violence, we also have to organize to make effective structural change in institutions, laws, policies, and beliefs that affect women, LGBTQIA+ people, and other minoritized groups. In our globalized world we must work together, within and across organized religions, to resist religious-based gender violence. Religious social justice activists are universally clear that their resistance comes from within their own religions and meaning-making, and they also need civil-legal support from the United Nations and the world’s pluralistic democracies (Longley, 2024; PrinciplesofDemocracy.org, n.d.).

The work of resistance is not against men or religion in general, but against systems of power and abuse, including religious systems and beliefs. For many activists, religious faith inspires their resistance, and they find guidance in interpretations of religious texts that suggest ways religion can support rather than harm people.

Learning Activity:

Examining Women’s Resistance to Religious Gender Violence

Objective: Students will examine and interpret the intersections of religion and gender violence, highlighting the resistance from the individuals below leading the charge within their faith communities.

- Divide the class into groups, with each assigned a topic from below:

- Nadia Murad (Yazidi genocide survivor): Explore how Nadia resisted sexual violence and trafficking under ISIS rule and how her faith and cultural identity influenced her activism.

- Malala Yousafzai (education): Explore Malala’s fight against the Taliban’s ban on girls’ education and her advocacy for girls’ rights, paying close attention to how she experienced religiously inspired violence against her.

- Leymah Gbowee (Liberian Women’s Peace Movement): Explore how Christian and Muslim women in Liberia collaborated across differences to end a civil war and resist religious violence against women.

- Shirin ʻIbādī (Ebadi) (Iranian judge and human rights advocate): Explore how ʻIbādī’s legal work intersects with religious law in Iran. Pay particular attention to her advocacy for gender justice within Islam.

- Mariam Ibraheem (Sudanese Christian activist): Explore her resistance to being sentenced to death under Sharia law for apostasy and the violence she faced for choosing her faith.

- Have each group choose an artistic format to represent their group’s activist story. Choose from drawing, performance art, music, poetry, or short story format.

- Have groups present their art to the class introducing each woman you have chosen to represent. Reflect and discuss.

Across the world, religious social justice activists continue to come together to actively resist religious violence. Groups such as the Interfaith Coalition Against Domestic & Sexual Violence facilitate local organization as well as legal fights to protect vulnerable populations (n.d.).

In India, women are reclaiming their deities to fight the taboos which have kept them out of their own religious sites during their child-bearing years. Muslims are using comics to challenge religious taboos about menstruation and create safe spaces for women and girls (Muslimahs Against Abuse Center, n.d.).

Coordenadoria Ecumênica de Serviço ([Ecumenical Coordination of Service], n.d.) in Brazil works across religious groups to defend human rights through political, economic, social, and environmental transformations toward democracy.

The UN and its organizations remain committed to the expansion and integration of human rights across the globe. The Nobel Peace Prize Committee continues to highlight brave individuals and organizations which embody bravery, compassion, and care for all humanity and enable them to speak and expand their work and influence.

Summary

There is no one right way to resist violence, but experience in a globalized world has taught us that multiple pieces of resistance are needed for effective progress. The answer is not to abandon religion, but rather to dig deeper into religious faith—to understand how and why people engage in religious meaning-making—to tether religion to a global understanding of human rights, and to creatively learn from the experiences of others. We all are making sense of the world around us and wondering what lies beyond our current lived consciousness. Some, like many young people across North America and Europe, can choose their religious faith; others, across much of the world, are born into their religious tradition. Regardless, as we grow and learn, we all have some measure of ability to choose how we will live, what is right or wrong, how we want to shape the future and why. Democracy has shown us that, while it is not immune from the effects of a hard-right religious push toward religious nationalism, it does offer a profound sanctuary for religious pluralism as long as the people of the democracy actively value and embody diversity and human rights (Longley, 2024).

As long as we draw breath, we hold power to resist religious violence, to uphold human rights for ourselves and others, and to listen to wisdom. Every person does meaning-making at the intersections of their identity—race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, physical ability, and age—and these change over time. We can choose to use religion to justify gender violence, or we can name religious violence, seek its cause, and transform cultural and religious practices into non-violent forms more in line with the core values of love and justice shared across religions. Surrounding ourselves with a mosaic of beliefs will push us to learn, grow more, advocate more, and stand up to religious violence together. Humans are an endless source of creative resistance against religious violence.

Review Questions

Questions for Reflection

- What role do religious institutions or religious teachings play in either supporting or resisting violence against women, transgender people, and LGBTQIA+ people, particularly in societies where religious beliefs heavily influence laws and cultural practices? How are women and transgender people particularly impacted by law and policy that is influenced by religious practices?

- How can grassroots activists, particularly women, queer people, and transgender people within faith communities, create spaces for resistance to religiously sanctioned violence? How can they transform religious practices and beliefs to promote gender equality and justice? Find concrete examples of activists doing this work currently.

- In what way does the UN Declaration of Human Rights help people from all religions in every country of the world live in increased safety and greater religious freedom?

- If there is common ground among religions like caring for the poor and choosing love over hate, then why is there so much religious conflict? How can we work together on shared religious ideals for the good of all the people in our community and world?

- What can you do to make sure your religious beliefs do not hurt other people? How do you make sure righteous anger at injustice does not fester into hatred or bitterness in you? How do you stay focused on what is good and live it out in your everyday actions toward other people?

References

Ajayi, C. E., Chantler, K., & Radford, L. (2022). The role of cultural beliefs, norms, and practices in Nigerian women’s experiences of sexual abuse and violence. Violence Against Women, 28(2), 465-486. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012211000134

Andaya, B. W. (2006). The flaming womb: Repositioning women in early modern Southeast Asia. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Bricker, V. (2022, September 12). When does life begin according to the Bible? Christianity.com https://www.christianity.com/wiki/bible/when-does-life-begin-according-to-the-bible.html

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2022, May 23). Wahhabism and the world: Understanding Saudi Arabia’s global influence on Islam [Video]. https://carnegieendowment.org/events/2022/05/wahhabism-and-the-world-understanding-saudi-arabias-global-influence-on-islam?lang=en

Carter, J. (2014). A call to action: Women, religion, violence, and power (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster.

Chesler, E., & McGovern, T. (2015). Women and girls rising: Progress and resistance around the world. Routledge.

Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians. (n.d.). Mercy Amba Oduyoye. https://circle.org.za/biographies/mercy-amba-oduyoye/

Cooke, M. (2019). Murad vs. ISIS: Rape as a weapon of genocide. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 15(3), 261-285. https://doi.org/10.1215/15525864-7720627

Coordenadoria Ecumênica de Serviço [Ecumenical Coordination of Service]. (n.d.). CESE: Affirming human rights. https://www.cese.org.br/en/

Despeux, C., & Kohn, L. (2003). Women in Daoism (1st ed.). Three Pines Press.

Edwards, K. A. (2022, July 15). Abortion Is power. Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2022/07/abortion-is-power.html

Eske, J. (2023, December 18). Can men become pregnant? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/can-men-become-pregnant

Farhadi, E., & Janjevic, D. (2024, September 16). Femicide in Iran: Tradition and law enable killing of women. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/femicide-in-iran-tradition-and-law-enable-killing-of-women/a-70228293

Flanagan, R. (2024). ‘Nobody ever told you, “actually, this feels great”’: Religion informed sexual health education and barriers to developing sexual literacy. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 7, 100343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2024.100343

Garvin, S. (2021). South and Southeast Asia. In S. Shaw (Ed.), Women and religion: Global lives in focus (1st ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Garvin, S. (2022). Religion in women’s lives worldwide. In T. Butts, P. Duncan, J. Lockhart &, S. Shaw (Eds.), Women worldwide: Transnational feminist perspectives (2nd ed.). Oregon State University. https://open.oregonstate.education/womenworldwide/chapter/religion-worldwide/

Gbowee, L., & Mithers, C. L. (2011). Mighty be our powers: How sisterhood, prayer, and sex changed a nation at war: A memoir. Beast Books.

Gross, T. (2024, February 9). Tracing the rise of Christian nationalism, from Trump to the Ala. Supreme Court. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/29/1234843874/tracing-the-rise-of-christian-nationalism-from-trump-to-the-ala-supreme-court

Hattenstone, S. (2019, April 20). The dad who gave birth: ‘Being pregnant doesn’t change me being a trans man.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/apr/20/the-dad-who-gave-birth-pregnant-trans-freddy-mcconnell

Human Rights Watch. (2005, July). International human rights law and abortion in Latin America. https://www.hrw.org/legacy/backgrounder/wrd/wrd0106/wrd0106.pdf

ʻIbādī, S., & Moaveni, A. (2006). Iran awakening: A memoir of revolution and hope (1st ed.). Random House.

Ibraheem, M., & Bach, E. (2022). Shackled: One woman’s dramatic triumph over persecution, gender abuse, and a death sentence. Whitaker House.

Interfaith Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. (n.d.). What we do. https://interfaithagainstdv.org /

Kasztelan, M. (2024, February 12). Will Poland’s new government legalize abortion? Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/02/12/poland-abortion-rights-pro-choice-election-coalition-pis-law-ban/

Kim, G. J.-S., & Shaw, S. M. (2024). Surviving God: A new vision of God through the eyes of sexual abuse survivors. Broadleaf Books.

King, M. L., Jr. (1967). Where do we go from here: Chaos or community? Harper & Row.

Kippenberg, H. G. (2011). Violence as worship: Religious wars in the age of globalization. Stanford University Press.

Kroll, A., Bernstein, A., & Marritz, I. (2023, October 11). We don’t talk about Leonard: The man behind the right’s Supreme Court supermajority. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/we-dont-talk-about-leonard-leo-supreme-court-supermajority

Le Roux, E. (2017). Men and women in partnership: Mobilizing faith communities to address gender-based violence. Diaconia, 8(1), 23-37. https://doi.org/10.13109/diac.2017.8.1.23

Longley, R. (2024, July 27). What Is pluralism? Definition and examples. Thoughtco.com. https://www.thoughtco.com/pluralism-definition-4692539

Maathai, W. (2007). Unbowed: A memoir (1st ed.). Anchor Books.

Maizland, L. (2023, January 19). The Taliban in Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-afghanistan

Marder, H. (2022, July 14). 25 comments about pregnancy and abortion from Republicans that prove they understand very little about women’s health. BuzzFeed. https://www.buzzfeed.com/hannahmarder/republican-lawmakers-comments-abortion

Mikhail, D. (2018). The beekeeper: Rescuing the stolen women of Iraq. New Directions Publishing.

Milne, P. (1989, March 25). Gensis from Eve’s point of view. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1989/03/26/genesis-from-eves-point-of-view/dc371184-1f4c-4142-ac2d-d5efee72a0da/

Murad, N., & Krajeski, J. (2017). The last girl: My story of captivity, and my fight against the Islamic State (1st ed.). Tim Duggan Books.

Muslimahs Against Abuse Center (MAAC). (n.d.). Teen awareness program. https://ma-ac.org/materials-for-learning

Nadeau, B. L., & Mortensen, A. (2024, March 9). Italy grapples with its patriarchal history as femicide cases shock the nation, CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2024/03/09/europe/italy-grapples-patriarchy-femicide-shock-intl

Nason-Clark, N. (1996). Religion and violence against women: Exploring the rhetoric and the response of evangelical churches in Canada. Social Compass, 43(4), 515-536. https://doi.org/10.1177/003776896043004006

Pakzad, S. (2021, May 13). Alireza: Alleged killing of Iranian gay man sparks outcry. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-57091251

Pew Research Center. (2022, December 21). Key findings from the global religious futures project. Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion 2022/12/21/key-findings-from-the-global-religious-futures-project/

Principlesofdemocracy.org (n.d.). Overview: What is democracy? https://www.principlesofdemocracy.org/what

Radford, J., & Russel, D. (Eds.). (1992). Femicide: The politics of woman killing. Twayne.

Roosevelt, E. (1940). The moral basis of democracy. Open Road.

Shahalimi, N., & Atwood, M. (2022). We are still here: Afghan women on courage, freedom, and the fight to be heard (1st American ed.). Plume.

Shaheed, Ahmed. (2020, August 24). Gender-based violence and discrimination in the name of religion or belief: Report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief. UN Human Rights Council. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3888744?ln=en&v=pdf

Sotoudeh, N. (2023). Women, life, freedom: Our fight for human rights and equality in Iran (P. Saranj, Trans.). Cornell University Press.

Stange, M. Z., Oyster, C. K., & Sloan, J. (Eds.). (2011). Encyclopedia of women in today’s world. SAGE Publications.

Stiehm, J. H. (2006). Champions for peace: Women winners of the Nobel Peace Prize. Rowman & Littlefield.

Stop Femicide Iran. (2024, July). Unveiling the silenced voices: Annual report 2023. https://stopfemicideiran.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/2023-ANNUAL-REPORT.pdf

Stop Femicide Iran. (n.d.). About StopFemicideIran. https://stopfemicideiran.org/about-us/

Stop Honor Killings. (n.d.). Campaign’s plan. https://stophonorkillings.org/en/campaigns-plan/

The Nobel Prize. (n.d.). The Nobel Peace Prize. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/

Türkkan, T., & Odacı, H. (2024). Violence against women: A persistent and rising problem. [Kadına Yönelik Şiddet: Kalıcı ve Yükselen Bir Sorun]. Psikiyatride Guncel Yaklasimlar-Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 16(2), 210-224. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.1291007

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime & UN Women. (2022). Gender-related killings of women and girls (femicide/feminicide): Global estimates of female intimate partner/family-related homicides in 2022. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/11/gender-related-killings-of-women-and-girls-femicide-feminicide-global-estimates-2022

United Nations. (n.d.). Women who shaped the universal declaration. https://www.un.org/en/observances/human-rights-day/women-who-shaped-the-universal-declaration

Yousafzai, M., & Lamb, C. (2013). I am Malala: The girl who stood up for education and was shot by the Taliban (1st ed.). Little, Brown, & Co.

Zoepf, K. (2016). Excellent daughters: The secret lives of young women who are transforming the Arab world. Penguin.

Further Learning

American Civil Liberties Union. (n.d.). Religious liberty. https://www.aclu.org/issues/religious-liberty

Armstrong, K. (2006, March 16). Karen Armstrong: Exploring the common ground between the world’s great religions. The Independent. https://www.the-independent.com/arts-entertainment/books/features/karen-armstrong-exploring-the-common-ground-between-the-world-s-great-religions-470137.html

Ghanea, N. (2023, August 21). Making freedom of religion or belief a lived reality: Threats and opportunities. UN Chronicle. https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/making-freedom-religion-or-belief-lived-reality-threats-and-opportunities

Jenkins, J. (2025, May 7). To put pressure on Trump, Democrats turn to religion—and religious activists. Religion News Service. https://religionnews.com/2025/05/07/to-put-pressure-on-trump-democrats-turn-to-religion-and-religious-activists/

Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. (n.d.). Support groups. https://www.snapnetwork.org/events

WORLD Policy Analysis Center. (2020, January). Constitutional equal rights across religion and belief [Fact sheet]. https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/constitutional-equal-rights-across-religion-and-belief-0

Media Attributions

- Happiness_in_togetherness © Shri Sourav Debnath is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) 4.0 license

- Woman_Life_Freedom_in_Nazrath_Mural © Nizzan Cohen is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 4.0 license

- 27758131387 © FDR Presidential Library & Museum is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 2.0 license

- Nobel_Peace_Prize_2011_Harry_Wad © Harry Wad is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) 3.0 license

- 52495098346 © Taymaz Valley is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 2.0 license