Campus Gender Violence Prevention Through Friendship

Whitney Archer and Elizabeth Kennedy

Abstract

Gender violence (GV) is an umbrella term describing not only types of violence that individuals may experience (i.e., stalking, domestic violence, sexual harassment, sexual assault) but also how systems create environments that allow violence to thrive. The United Nations Populations Fund states that GV “is one of the most prevalent human rights violations in the world; gender-based violence knows no social, economic or national boundaries. It undermines the health, dignity, security, and autonomy of survivors. And it remains shrouded in a culture of silence, supported by cultural beliefs and values that sustain, justify or dismiss it. . .” (UN Population Fund, 2023). This chapter addresses GV within the context of colleges and universities.

We anchor this chapter in our personal experiences working as feminist scholar-practitioners situated in the United States, while also being informed by global movements to end violence. Our relationship as colleagues and friends has served as a sustaining force in our efforts to address and eradicate GV. Elizabeth is a GV educator and strategist whose work and research focuses on cultivating a love ethic as a foundational framework to transform university practices and policies related to gender violence prevention efforts. Whitney is a diversity and social justice educator whose research on anti-racist feminist praxis informs their work supporting identity-based cultural resource centers.

Learning Outcomes

- Students will describe some of the historical and structural factors that tend to work against eradication of gender violence on campuses

- Students will describe the authors’ combination of brown’s emergent strategies for transformation and Linder’s power-conscious frameworks (PCFs), and analyze the advantages of this approach to gender violence resistance work on campuses

- Students will identify some of the benefits of collaborating/co-laboring with others to build coalitions using friendships and strategies of care to resist gender violence on campuses

Co-laboring to Resist GV on Campuses

In a US context, the 1987 scope of rape study surveying more than 6,000 college women is often noted as foundational for calling attention to the pervasiveness of GV on college campuses (Koss et al., 1987). This study found that one in four college women had experienced an attempted or completed rape, and 84% knew their attacker. In the years since, multiple independent research teams have found comparable prevalence rates (Campbell & Wasco, 2005). “For millions of students each year, college is a place of peril, a place where they encounter and then must cope with the aftermath of gender-based violence” (Marine & Lewis, 2020, p. 1).

GV on college campuses is an international issue; drawing from multiple research studies, the United Nations provides the following prevalence rates: 51% of college students in Australia reported incidents of sexual harassment and 6.9% experienced sexual assault; 76% of college women in Bangladesh faced sexual harassment; 62% of Spanish students witnessed or experienced some form of GV; and 70% of women at Cairo University in Egypt experienced sexual harassment (UN Women, 2018, p. 6). Globally, one third of women report having experienced some form of GV, and as many as 38% of all murders of women are committed by intimate partners (WHO, 2024). These rates are startling and overwhelming; yet we must understand the scope and prevalence of violence in order to address it.

Campus Landscape and Resources

On numerous campuses GV services have roots in women and gender equity centers, which have played a central role in advocating for institutional change and have served as hubs of feminist activism (Marine et al., 2017). Feminist activism has led to many significant advances and societal changes to address GV, including the creation of domestic violence shelters, rape crisis centers and campus-based resources and services, access to abortion, as well as law and policy changes (Marine & Lewis, 2020). Campus resources and programs that attend to GV awareness, prevention, and response can vary greatly. In the US, federal funds are tied to compliance, and thus the presence of compliance offices is standard. Beyond compliance offices, the number and type of resources on a campus often communicates their beliefs about and approaches to GV. Common resources to look for on your campus include advocacy centers, student clubs and organizations, prevention and education programs, survivor-focused mental health services, sexual health programming, women and gender equity centers, and peer education programs. You can also look into academic programs, including women, gender and sexuality studies, for classes about GV awareness and prevention.

Learning Activity:

Mapping Campus Resources for Gender & Sexual Violence Prevention

Objective: Students will explore the gender and sexual violence prevention efforts on their campus. This will familiarize them with necessary resources and highlight the importance of advocacy work on college campuses while also fostering responsibility for preventing gender and sexual violence in their community.

- In groups of three or four students, identify the following offices, resource centers, or resources on your campus:

- Title IX office or student legal aid office

- Counseling services

- Sexual assault prevention services/survivor services

- Student groups affiliated with violence prevention

- Emergency hotlines

- Public safety office

- Student health services

- Using a map of the campus, circle key resources you have identified and write a brief description of those resources. Make sure to create your own map key that indicates any available online or phone-only resources

- As a class, share the resources you have found with your classmates, and reflect on the importance of these resources while answering the following questions:

- Are certain resources lacking or hard to find on your campus?

- What barriers exist that prevent students from accessing these resources?

- What can be done to increase awareness of gender and sexual violence on your campus?

Feminist Friendship

This chapter is grounded in our friendship as feminist practitioners in higher education working collaboratively, and sometimes subversively, to engage with our community in efforts to end GV on campus. Our work, individually and collectively, has been informed and sustained through friendships. While we have been colleagues since 2016, we did not begin intentionally working together in a meaningful way until 2018. That work began with an apology. I (Whitney) was directing the Women & Gender Center when Elizabeth was hired to assist with university prevention efforts, and while there were clear connections between our work, organizationally, prevention efforts were intentionally limited to the work of one small department. Elizabeth was discouraged from building the relationships she knew were crucial to GV prevention efforts, and the prevention efforts coordinated by the Women & Gender Center were blocked.

Following organizational restructuring, I (Elizabeth) had an opportunity to shift campus prevention efforts and knew that it had to begin by taking accountability for the detrimental impacts of the previous territorial model. I referred to this work as my “Apology Tour,” and the first stop on this tour was Whitney’s office. I acknowledged the harm and impacts that had been caused and asked Whitney what they needed to build trust. Whitney generously stated that they were willing to start at a place of trust. I (Whitney) was appreciative of Elizabeth’s vulnerability, and much of what she shared aligned with some of my own observations about the patterns of prevention work on our campus.

My offer to start at a place of trust was meeting Elizabeth with the same trust she showed me in reaching out to connect. We both believe that there is a place for everyone in prevention work, and coming together allowed us to coalesce around that shared value. This was a meaningful shift in our relationship and the starting place for transformation we’ve experienced as friends and collaborators in this work. Our shared understanding of relationships and the practice of friendship is deeply informed by adrienne maree brown’s writing on emergent strategy. She offers that “[e]mergent strategy is about shifting the way we see and feel the world and each other. If we begin to understand ourselves as practice ground for transformation, we can transform the world” (brown, 2017, p. 191).

The friendship we cultivated took time and we’ve both experienced it as being distinctly feminist. It’s personal and political. We slowed down and got to know each other beyond our roles as university administrators. We help make space for each other to vent, to laugh, to cry. We’ve encouraged and challenged one another. We’ve shared recent pics of our pups (Elizabeth) and kids (Whitney) and built a foundation that allowed for vulnerability and transformation. As Laura Rendón offers

[t]aking time to slow down and reflect is as important to spending time and energy and action to transform the institution. The work of transformation is not only about changing what’s “out there”; it’s about transforming what’s “in here,” our own internal views and assumptions (2009, p. 48).

brown (2017) refers to this mutual transformation as co-evolution and states that it is some of our deepest work. Our friendship has been a source of strength and joy for both of us in this challenging work. Anchored to our feminist orientation, we position GV on college campuses as deeply connected to and influenced by all systems of dominance. Feminism requires us to account not just for sexism, but for the material realities created by interlocking and simultaneously experienced systems of oppression (Taylor, 2017). We can never adequately address GV if we do not account for all forms of violence and oppression. We believe that a world free from GV is possible and that there is a place for everyone in prevention work. Our friendship has been formative to expanding that belief and connecting it to action. In their writings on the importance of coalitions in GV prevention, Marine and Lewis taught us that the original meaning of collaboration is co-laboring, and go on to offer that collaboration

requires humility and a deep consciousness of one’s own privileges, as those of differing social positions and priorities seek mutual understanding and alliance. It offers, in return, the opportunity to weave transformational efforts into the full fabric of a university, as co-laborers bring the richness of their diverse insights and locations to the change table. (2020, p. 3)

As you engage with this chapter, we invite you to reflect on what role(s) you can play to eradicate violence on your campus and to consider who your co-laborers could be.

Friendship as Central to Realizing a Power-Conscious Framework

Fellow feminist scholar Chris Linder developed a power-conscious framework (PCF) for approaching sexual violence awareness, prevention, and response on college campuses. Her framework draws on critical consciousness (Freire, 2000/1970; hooks, 1994) and intersectionality theories (Crenshaw, 1991) and links the connections between power and sexual violence. She specifically articulates how “rape as tool of power and control” (Linder, 2018, p. 9) was used by White European colonizers over Indigenous and enslaved people to instill fear and to expand both land theft and economic power. From police violence and other forms of state-sanctioned violence to perpetrators targeting minoritized people (i.e., women of color, people with disabilities, and queer and trans people) at higher rates (Linder, 2018; Marine & Lewis, 2020), patterns of domination and use of power persist.

A power-consciousness framework requires scholars, activists, and policymakers to consider the role of power in “individual, institutional, and cultural levels of interactions, policies, and practices” (Linder, 2018, p. 14). We resonate with Linder’s framework as it challenges us, and others seeking to eliminate GV, to develop strategies that attend to both the roots and the symptoms of oppression. The framework is grounded in the following three foundational assumptions: (1) power is omnipresent, (2) power and identity are inextricably linked, and (3) identity is socially constructed. Anchored in these assumptions are six action-oriented tenets:

- Engage in critical consciousness and self-awareness

- Consider history and context when examining issues of oppression

- Change behaviors based on reflection and awareness

- Name and call attention to dominant-group members’ investment in, and benefit from, systems of domination

- Name and interrogate the role of power in individual interactions, policy development, and implementation of practice

- Work in solidarity to address oppression

We suggest that friendship is a foundational modality through which the tenets of a PCF to address GV can be realized.

Throughout this chapter, we map a component of brown’s (2017) co-evolution through friendship onto each tenet of Linder’s (2018) PCF to illuminate the ways friendship has been a conduit for applying theory and enacting change. In each subsection we provide examples from our friendships and work together. The sidebars provide further examples of how each PCF tenet can be applied in day-to-day actions to prevent GV, to provide inspiration from different activists and movements.

Continual Growth

Learning and growth are foundational in the work to address GV. The phrase “continual growth” draws upon the PCF tenet to engage in critical consciousness and self-awareness (Linder, 2018) and brown’s (2017) co-evolution through the friendship element of self-transformation. Linder describes engaging in critical consciousness and self-awareness as the on-going process of reflecting on who we are and how we show up in the world, as well as how that differs from those who hold different identities than we do. Self-awareness is crucial for noticing the role power plays in everyday actions and in systems. Linder makes clear that critical consciousness and self-awareness is a starting point, not the end point, of social justice work (2018, p. 26). Pairing this tenet with self-transformation, brown (2017) reminds us that we must remain open to our own change and transformation, and that as microcosms of the world, shifting the oppressive patterns within ourselves is a demonstration of the power that exists to change oppressive systems in the world. As student affairs practitioners and educators, we can easily get caught up in teaching others and forget that we too have learning to do. We align with Sara Ahmed’s reminder that, “[t]o become a feminist is to remain a student” (Ahmed, 2017, p. 11).

Through our friendship, we often remind ourselves and each other we didn’t always know the things that we currently know. Those reminders help us to hold space for both ours and others’ learning. Our friendship helps to keep us humble and accountable. The goal of eliminating GV is a daunting task and to do it, we need as many people as possible brought into the work. Elizabeth always frames this as, “I want everyone on team prevention.” People will show up with differing levels of knowledge to a workshop or program we offer, and that is okay. Shame is a terrible teacher, and we’re not interested in shaming someone for not having a base-level knowledge of how GV shows up in our communities. For example, a participant might genuinely not have known what victim-blaming is or that it is highly problematic, and they are very welcome in our spaces and programs. If we were to shame them for not having this knowledge, why would they ever join in community efforts to stop violence? Their engagement with our programs can play an important role in supporting their self-reflection and critical consciousness raising.

As friends doing this work together, we are able to help each other continually grow by helping one another see our strengths and also where there is room for us to develop. I (Elizabeth) can struggle to trust myself. This can lead me to overthinking and over-analyzing, which ultimately makes the work even more challenging. Whitney has been helpful in strengthening my ability to trust my knowledge and critical thinking. Sometimes this has simply been an encouraging reminder of, “You’ve got this, you’re good at your job, you know what you’re doing and what you’re talking about.” It can also be Whitney holding space for me to verbalize my thinking and draw my own conclusion. Whitney’s work overlaps with GV prevention and advocacy; however, doing this work is not the primary focus of their position description.

Since doing GV work is what Elizabeth does full time and is the entirety of her position description, she has been able to help Whitney better understand our campus GV landscape, including the potholes. When navigating a campus policy failure, Elizabeth, in addition to amplifying my concern within her sphere of influence, coached me on where to push and what language to use when working with campus partners. Additionally, Elizabeth has helped me to strengthen the use of consent practices within the Women & Gender Center and other campus cultural centers. Examples include having student staff consent to the use of their name, photo, and other identifying information shared on websites and social media, giving students up front information about how photos taken at an event or program may be used, and giving them the opportunity to opt in or out of being photographed. Our experiences of co-laboring together have included a full range of emotions, from rage and discouragement to hope and joy. Through it all, our friendship has been a laboratory for learning the support of our continual growth.

“You Might Be Causing Harm If . . .” Poster Campaign at the University of Utah

Designed by student staff, these posters speak directly to their peers about common behaviors that have been “normalized” but are problematic; at a minimum are hurtful, but all too often result in violence.

Example prompts include, “You might be causing harm if…”:

- You think it was just a bad hookup and they’ll just get over it

- You ignore signs that your partner isn’t enjoying themselves

- You talk someone into having sex with you

This campaign was designed to shift the focus to “raising awareness about how to not cause harm rather than how to avoid it” (Hills & Adams, 2023, p. 3) and is an example of how to engage students in a process of critical consciousness raising (Linder, 2018) and self-transformation (brown, 2017). The posters were combined with blog posts linked with the posters via a QR code. Analytics of the scans as well as media and social media engagement point to the success of the campaign at reaching their campus community.

Context Matters: Looking Back, Noticing the Present, Changing the Future

In this section we weave together brown’s (2017) element of pattern disrupting with Linder’s (2018) call to consider history and context when examining issues of oppression. “Oppression did not happen in a vacuum and did not emerge overnight” (Linder, 2018, p. 27). Tracing the patterns of how oppression evolves and is woven into the fabric of our relationships, institutions, policies, and practices allows us to see them as just that: patterns. Patterns can be disrupted. We use this section to further contextualize GV histories and the current landscape of GV on college and university campuses.

History Matters

Across history, sexual violence has been pervasive in times of conflict and war, and as long as there has been GV there have been forms of resistance. The work to address and respond to GV has a long history, often community-based, and led by women of color. In the United States, GV is deeply entangled with the ongoing project of colonization, and Indigenous women have been at the forefront of resistance efforts. In her book, Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims, Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins, the first Indigenous woman to publish a book, speaks about Indigenous women experiencing sexual violence at the hands of white European men, while white European women did nothing to intervene (Winnemucca, 1883).

In 1974, the Combahee River Collective, a group of Black lesbian feminists, began meeting to confront various manifestations of oppression, including violence against women and girls. Their historic Combahee River Collective Statement introduced the concepts of interlocking systems of oppression and identity politics, and highlighted their experiences of sexism in Civil Rights organizing and racism within feminist movements (Taylor, 2017). “Thus, from the very inception of the anti-violence movement in the United States, Black women, and Black lesbians in particular, have been both central actors and challengers to the approaches and practices of the predominantly white antiviolence movement” (Incite, 2016, p. 9). As white practitioners working to address GV, we feel accountable to the women of color whose labor informs our work and is often rendered invisible within mainstream GV organizing. We also track common erasure and minimization of the violence against marginalized communities.

Context Matters

“Antiviolence work must, by definition, be conscious of and accountable to communities not historically well served, including women of color, trans and queer survivors, and those whose ability status or socioeconomic position render them less empowered in academia. Otherwise, it runs the risk of replicating the violences of academia endemic to power unconsciousness.”

(Marine & Lewis, 2020, p. 17)

Doing GV work within US higher education, we must attend to the ways legacies of violence are woven into the fabric of our campus climates and cultures. American colleges were built upon stolen Indigenous lands, often by enslaved labor, and played a significant role in the expansion of slave-based economies (Grande, 2018; Wilder, 2014). Even within the US, regional differences and campus type (i.e., community colleges, Historically Black Colleges & Universities, Predominately White Institutions) must be considered when developing strategies to address GV. Accounting for context highlights that “[t]he common driver of the work—collective resistance to patriarchal norms and a deep desire to create safer campus cultures—does not dictate sameness of practice, only sameness of resolve” (Marine & Lewis, 2020, p. 9).

Legal Matters

The legality of GV varies across the world. The first sexual violence laws in the US were property crime laws, meaning White owning-class men were the only people who could file sexual violence charges. “If their wives or daughters were raped or sexually violated, men could claim that their property had been violated” (Linder, 2018, p. 27). Globally, including within the US, many countries have societal norms that permit physical and verbal abuse; and as of 2017, 49 countries had no specific law against domestic violence, 45 countries had no legislation to address sexual harassment, and 112 countries did not criminalize marital rape (World Bank Group, 2017).

Internationally, policies and legislation for holding campuses accountable for addressing GV vary greatly in their content and strength. Several international and regional frameworks, including the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action; the 1979 United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; the 1994 The Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women (known as Belem do Para Convention); and the 2003 Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (known as the Maputo Protocol) have been taken up to help address GV in public and private spaces, including educational settings (UN Women, 2018).

In the United States there are a variety of laws and regulations, both federal and state, that determine how universities craft and enact sexual misconduct policies. The most recognized is Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (2018). Title IX was signed into law on June 23, 1972. The law was introduced by Congresswoman Patsy Mink, who was motivated by her own experience of discrimination as a woman of color. Title IX prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in educational programs or activities receiving federal financial assistance. The law has had large impacts on access to athletics, but applies to all aspects of education, including admissions, financial assistance, academic programs, and employment. Title IX has been crucial in promoting gender equity in education and has been taken up as a legal tool for holding institutions accountable for GV. Under Title IX, schools are required to investigate and address complaints of sexual harassment and assault. The law has been instrumental in raising awareness about the prevalence of sexual violence on college campuses and has led to the development of programs and policies aimed at preventing and addressing sexual assault. It is important to know that Title IX is dynamic and its interpretation has shifted under different presidential administrations and by Supreme Court rulings. A pattern across all of these policies, frameworks, and legislation is that they fall short, and are insufficient in their ability to address GV.

Future Matters

Weaving together brown’s (2017) element of pattern disrupting with Linder’s (2018) call to consider history and context when examining issues of oppression provides a framework for looking back, noticing the present, and changing the future. We have helped each other notice patterns on our campus, including territorial approaches to GV, the university caring more about looking like it’s doing the “right things” versus actual change, and a focus on compliance over primary prevention. In noticing these patterns, and raising them together, it is harder for the university to ignore us. Friendships are also systems and we also interrogate patterns between us and hold each other accountable to make sure we are not replicating oppressive moves, and in doing so we embody brown’s (2017) reminder that “what we practice at the small scale sets the patterns for the whole system” (p. 53). Through our friendship we have tracked patterns and practiced new ways of being with each other.

Keetsahnak: Our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Sisters

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people (MMIW2S) is a movement that seeks to highlight and address the disproportionate rates at which Native and Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people are stolen and killed across Canada and the US.

Keetsahnak: Our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Sisters is a moving collection of essays that centers Indigenous voices and situates personal stories of trauma and violence in relationship with colonial histories and legacies across Canada. The collection centers Indigenous responses to gendered and sexual violence and offers models for community-based grassroots activism that center Indigenous knowledges (Anderson et al., 2018).

Know Better, Do Better

Each of us are a work in progress, and change requires action. brown’s (2017) notion of being present and intentional complements Linder’s (2018) call to change behaviors based on reflection and awareness as they both highlight the cyclical relationship between reflection, awareness, and choice. Linder’s articulation of behavior change reminds us if we do not couple awareness with action, we are part of the problem.

Our campus (Oregon State University), like many worldwide, hosts an annual Take Back the Night (TBTN) event. There are several origin stories of TBTN; some trace the roots to an 1877 event in London (Syracuse University, n.d.), other stories indicate it started in the 1970s with two independent marches responding to violence against women, one held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US and one in Brussels, Belgium (Gibson, 2011). From these early protests grew a movement of annual events, often including marches and survivor speak-outs that take place on college campuses and in communities around the world. A former colleague who coordinated TBTN on our campus took great pride in the number of people who attended the event, equating a large crowd with success. The crowd often included high level university administrators. The tone of the event felt curated to showcase the “good work” being done to support survivors, and left little room for critiquing our shortcomings and areas of needed improvement. Over the years, I (Whitney) had received feedback from students about their suggestions and ideas not being welcome in planning meetings and that the event felt performative.

In 2019, a group of student leaders, including Women & Gender Center staff, wanted to shift TBTN, and got involved in the planning committee. They were excited about centering women of color and the inclusion of a performance by women of color student dance group, many of whom identified as survivors of GV. That excitement quickly shifted to pain and frustration upon the group being uninvited to perform based on our colleague’s perception that their dancing was “inappropriate” and “too sexual.” The students named this response as slut shaming; the act of condemning someone, usually girls and women, who are perceived to violate societal norms regarding appearance and sexuality.

Upon hearing this from students and colleagues, including one from another campus, I (Whitney) reached out to other co-laborers in this work—Kim, who worked in our survivor advocacy center, and Sahana, who coordinated survivor support in our counseling center—to seek clarity and to consult on arranging support for impacted students. We coordinated a care circle for students, and reached out to our colleague who caused harm. Bias reports were submitted and a meeting was set for the student planning committee to meet with our colleague; Sahana was invited to attend in a support role for the students. The meeting did not go well and the majority of the students withdrew from the planning committee. The former TBTN planning committee, along with additional student leaders from Women & Gender Center and other campus partners, channeled their energy to create an alternative event titled Reclaiming Resilience. The event was a beautiful gathering centering survivors of color, including queer and trans survivors, and was grounded in healing, wholeness, and self-expression. Students created art, shared poetry, and felt held in community. The success of the Reclaiming Resilience event stands as a reminder that the impact of our programs can never be measured simply by the number of people they reach.

Responding to the harm students experienced was a moment to be reflective (Linder, 2018), present and intentional (brown, 2017), “to recognize where we have choice” (p. 195). In relationship with Kim and Sahana we listened to the students’ feedback as an opportunity to make the choice to do better. At this time, Elizabeth was still in a phase of building campus connections beyond her immediate office and during this incident she provided support to Kim, Sahana, and I (Whitney) that helped to shift collegial relationships to friendships. These friendships provided courage to start taking risks together. It also created an opportunity for self-reflection. Watching my colleague distance herself from the harm she caused taught me (Whitney) a lot about leadership and the importance of accountability. We are going to make mistakes in this work and when we do, we must be accountable. Our friendships with Kim and Sahana, who have both left our university, continue to be places of accountability for both of us.

Sarah’s Place: A Safe Place to Heal

Founders of Sarah’s Place understood that medical institutions were failing survivors who reached out for services and set out to create a more survivor-centered facility. Opening in 2016, Sarah’s Place is the first sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) center in Oregon, USA. Staffed by SANE nurses with specialized training, their facility offers private exam rooms, consultation rooms for patients and families, and a private shower. Sarah’s Place is open 24/7 and provides support, including free medical and forensic care and access to community resources (Samaritan Health Services, n.d.).

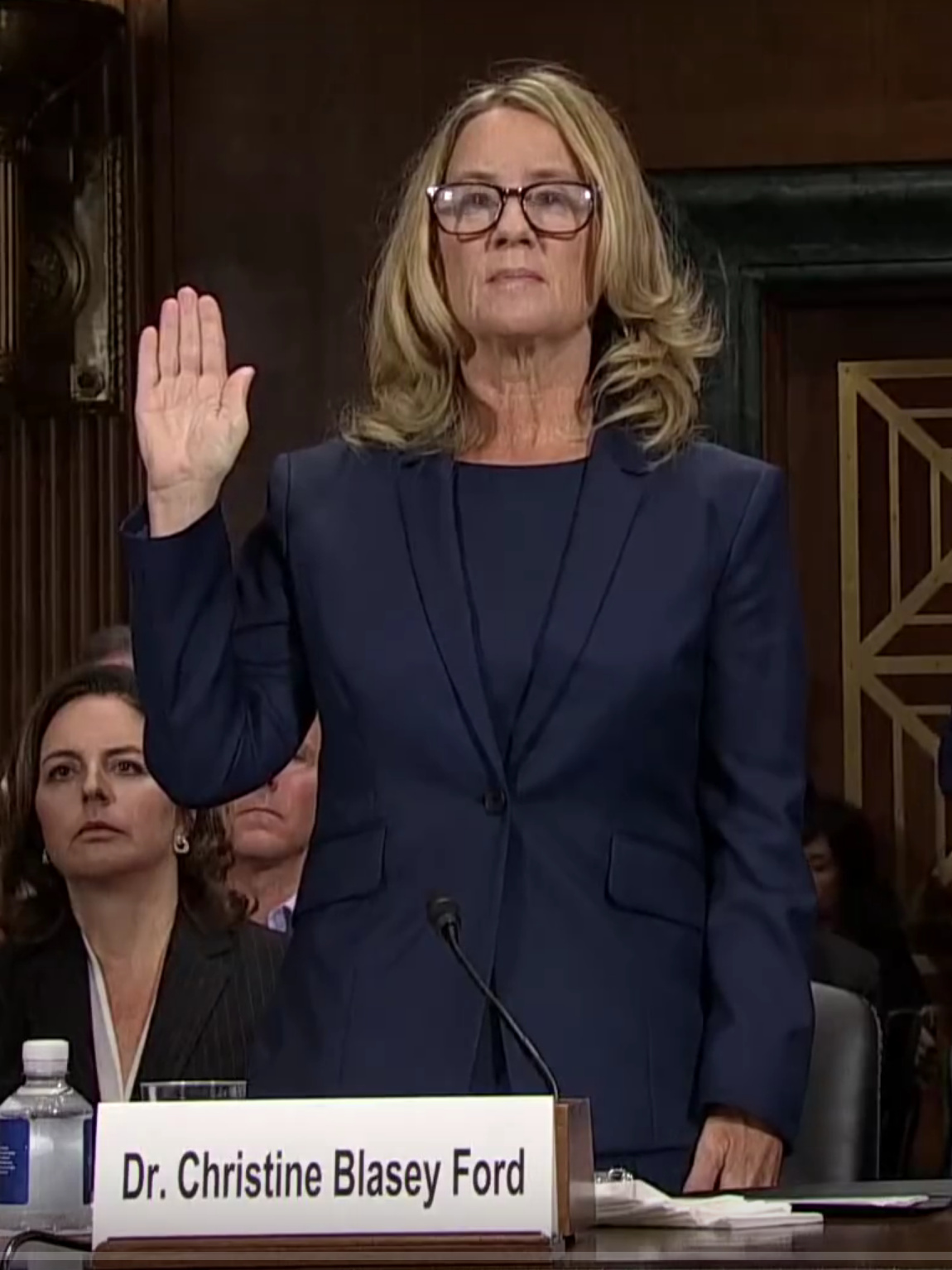

Speaking Truth to Power

The fourth tenet of Linder’s (2018) PCF is to name and call attention to dominant group members’ investment in, and benefit from, systems of domination; we pair this with brown’s (2017) practice of vulnerable reflection. In late September 2018, we watched as Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee for Judge Brett Kavanagh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing. Ford’s testimony detailed her sexual assault by Kavanagh, in 1982 when they were both in high school. Ford powerfully responded to questioning for over eight hours. At stake was Kavanaugh’s potential lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court.

News media and our social media feeds were saturated with content connected to the hearing. The court of public opinion debated Ford’s credibility, demonstrating the pervasiveness of rape culture and the normalization of violence. While hoping otherwise, we felt Kavanagh’s confirmation was inevitable. After all, systems in their current form privilege people with dominant identities, and people with power are commonly invested in maintenance of those systems (Linder, 2018, p. 29-30). I (Whitney) sat overwhelmed with students in the Women & Gender Center and decided to reach out to campus partners, including Elizabeth, Kim, and Sahana to see their interest in writing a collective message to share out to the campus community regarding our commitment to supporting survivors. Vulnerable reflection means reaching out to one another with honesty (brown, 2017). I reached out because I was both angry and sad; I also felt alone.

Reaching out reminded me that I wasn’t alone. Together we were able to author a letter that none of us could have done on our own without professional implications. We took a risk together to speak truth to power. In our roles as student affairs professionals at a public university, our ability to speak out is limited. As we sought to get our message shared out, university officials attempted to revise it. This attempt was university powers wanting to control messaging that was designed specifically to interrupt the dominant narratives about sexual violence that were permeating the current media cycle. We wrote a letter that could have been sent from our offices any day of the year and we knew that those who needed to hear it as response to the current moment would. Our Believe Survivors message did not rely on systems to determine the validity of a survivor’s experience.

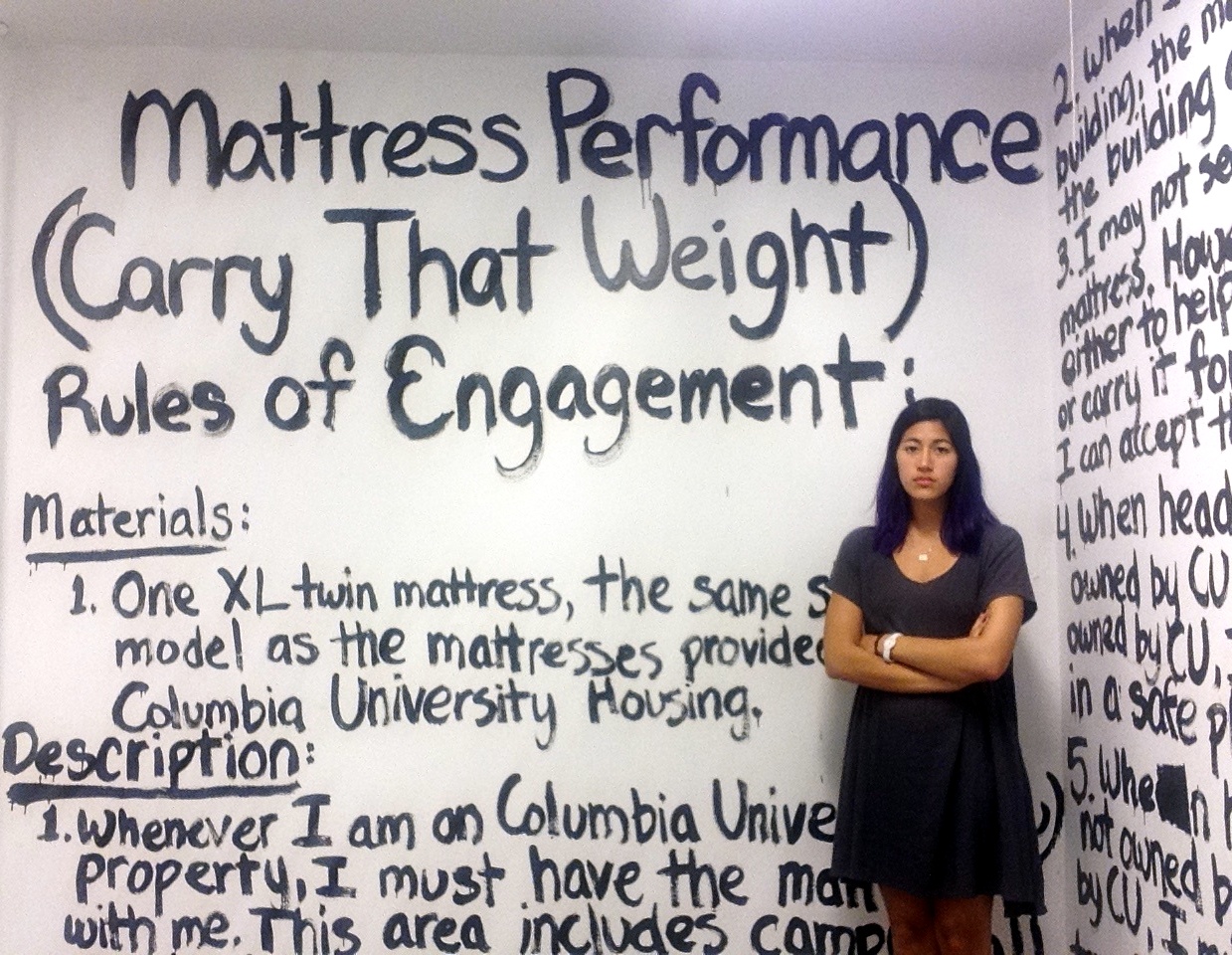

Carry That Weight

During her undergraduate studies at Columbia University, Emma Sulkowicz turned her senior thesis into a creative piece called Carry That Weight.

Sulkowicz was raped at the beginning of her sophomore year. After meeting two other women who were raped by the same student, Sulkowicz decided to report her assault. During a hearing Sulkowicz reported, “One panelist kept asking me how it was physically possible for anal rape to happen. I was put in the horrible position of trying to educate her and explain how this terrible thing happened to me” (Sulkowicz, 2014). The administrators at Columbia University charged with hearing the Sulkowicz case concluded that the student accused of raping Sulkowicz had not broken the university’s sexual violence policy. The accused student was allowed to remain on campus. Sulkowicz appealed this decision, but Columbia University’s decision was sustained. In protest and as part of the Carry That Weight project, Sulkowicz vowed to carry her dorm room mattress everywhere on campus until the student accused of raping her was expelled by the university or the student left the university on his own.

Curiosity Creates Possibility

Beyond noticing the ways that individual people invest and benefit from systems of oppression, a PCF requires us to pay attention to the ways power operates in interactions, policies, and practices. Linder (2018) and brown’s (2017) practice of curiosity provides us a modality through which to observe and interrogate these manifestations of power. Staying curious can create possibility.

Following a high-profile incident on our campus connected to Title IX, our university created a steering committee to conduct a comprehensive review and assessment of our GV prevention, support, and response programs and services. Ironically, as the only person on campus doing GV prevention work as my full-time job, I (Elizabeth) was not invited to participate in this committee. I was curious as to how an honest comprehensive review and assessment of prevention could be accomplished without the insight of the person tasked with this work. Sahana and I (Whitney) were invited to the steering committee and had the same curiosity. We raised the question to the group; it, along with other questions we raised, were viewed as inconvenient and were shut down.

brown (2017) states that curiosity is about asking authentic questions and believing the answers are important (p. 194). In this case, the silence with which our questions were responded to spoke volumes. It became clear that the committee was not going to result in any meaningful change. Driven by fear, the culture of compliance, which undergirded the committee, restricted our progress. The pervasiveness of compliance culture limits the ability for campuses to implement meaningful prevention education (Marine & Nicolazzo, 2020). Ultimately, the group met three times and a report was submitted to university leadership.

Shifting from Compliance to Care

A common pattern we’ve noticed, and been punished for both noticing and naming, is campuses emphasizing compliance over care. Campuses prioritize their legal risks over dismantling systems that allow GV to thrive. Invoking brown’s (2017) practice of pattern disrupting, we suggest an investment in primary prevention and posit a shift from compliance to care. Although the intention of laws and policies has been to provide care, it is our observation that universities have used Title IX and related policies to rigidly apply compliance and in turn create, knowingly or not, uncaring environments for the folx these laws are meant to protect. Whereas primary prevention shifts the focus from individuals to the community, and empowers the community to see itself as part of the solution to ending GV, and in doing so allows for the possibility to place care as the foundation.

The term “prevention” gets thrown around a lot in higher education, and is often equated to policy work, but this does not accurately represent the full scope of prevention work. There are three types of prevention: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary prevention is efforts that work to address root causes of violence and seek to stop violence before it occurs. Secondary prevention is strategies that work to increase knowledge that violence is an issue and one that needs to be addressed. Tertiary prevention is how a community reacts and responds to violence, which includes campus policies and compliance efforts (Foster et al., 2019). To have comprehensive prevention efforts on our campuses, all three types of prevention must be happening. Yet it is common for tertiary efforts to be given priority. To move towards comprehensive efforts and away from compliance culture, we must move toward primary prevention.

The aim of primary prevention education is to help the community see themselves in the work and as part of the solution. Providing GV primary prevention education can help community members see and acknowledge how our systems and structures have and continue to perpetuate violence and inequitable outcomes. Primary prevention education can help get communities closer to systemic transformation and help them to consider how they can work to change the environment that allows GV to thrive.

We often see institutions run from prevention because there is fear that if the focus is on prevention, that must mean there is a problem, and institutions become consumed with liability and perceptions. Primary prevention actually offers a reframe: We know that people in all communities, including our own, experience GV—and we are dedicated to eliminating it. This may be why primary prevention work in a university context feels subversive and radical, when in reality it is just solid prevention work. Even so, these subversive and radical feelings exist, likely because universities are risk averse and do not consider primary prevention work as valuable as policy work, which helps protect liability.

I (Elizabeth) was initially upset and frankly baffled that I was not part of this group. However, at this point in my career I had watched power moves like this all the time, so although I was mad, I was not distracted by this enough to keep me from staying the course and continuing doing the work. Months after the committee wrapped up, I received an invitation to meet from the university administrator, who charged the original steering committee, about the work I was doing. I was not going to miss my opportunity to share what was being done and what was possible if efforts were made to invest in support for prevention. I reached out to Whitney, Sahana, Kim, and our colleague Amanda to read a report I assembled to take to this meeting. The meeting was set to last for 45 minutes, but lasted for two hours, as the administrator asked me to walk him through the 16-page report. He was surprised to learn of all the work we were doing and was excited about the possibilities of what prevention could offer our campus.

Staying critical of power and remaining curious, ultimately allowed me to keep my prevention educator hat on and helped an administrator see the possibility that prevention could provide our campus. These elements continue to guide our prevention efforts and have resulted in transformative (Marine & Lewis, 2020; Marine & Nicolazzo, 2020) programming, including this year’s Imagining a World Without Sexual Violence event coordinated by our peer educators.

The peer educators invited our campus to create a visual representation of what the world would look like without GV. They then compiled all the art and shared it with campus in a digital zine. This process invited us to consider how we too have internalized power and oppression and how we might remain curious in how we disrupt these narratives and bring new futures to life.

Through our co-laboring we’ve been able to mitigate the feelings of isolation and the ways we’ve been positioned as the problem, or confused ones when we ask critical questions or point out observations of the ways our university is failing to attend to histories and complexities of GV work. Friendship, co-laboring, and curiosity, have world-changing transformative potential.

For Survivors by Survivors

Created in 2018 at the University of Michigan, the “For Survivors by Survivors: A Healing Resource Co-Creation” art project was developed through contributions to an anonymous survey that provided an opportunity for survivors to share materials that have been helpful in their healing process. This project de-centers institutional power and knowledges and is grounded in survivors’ wisdoms and expertise. It includes books, poetry, songs, movies, and shows that survivors have found helpful in their healing processes (Sexual Assault Prevention and Awareness Center, 2018).

Solidarity: Bringing It All together

“[W]orking in solidarity with one another, taking turns, tagging out when exhausted, and holding each other accountable in social justice work are vital” (Linder, 2018, p. 32) and can only be fully realized through the application of all five practices of brown’s (2017) framework for the co-evolution through friendship (self-transformation, curiosity, vulnerable reflection, pattern disrupting, present and intentional). The following example is the coalescence of these combined frameworks: None of our best work is done in isolation; it’s done in community.

In the summer of 2020, our university hired a new president, and by November there were rumblings from his former institution that an investigation was underway related to mishandling of cases of sexual misconduct. The University was frantic. During this time, we and some of our colleagues drafted an open letter to survivors of gender violence. Our goal was to remind survivors (students, faculty, and staff) that we love them, and share where they could seek confidential support on campus. This letter spurred lots of generative conversation on our campus, which helped lead to the university community calling for the president’s resignation in the wake of this unveiled knowledge.

It is important to note that our letter was not the only thing that set positive change in motion. There were many reactionary meetings, and the reactionary nature of these meetings was underscored by causing more harm: limiting survivors’ talking time, cutting them off in the middle of testimony to the Board of Trustees, and well respected faculty coming to the defense of the president. Tensions were understandably and rightfully high. These missteps highlighted the need to have more conversations on campus about what was being done to support survivors and prevent GV. The students, faculty, and staff at the university pushed back against the reactionary and hurtful ways the institution moved in the wake of these findings. The faculty and staff held a vote of “no confidence,” and the president eventually resigned.

Stretch Yourself to Build Solidarity

Musician, cultural organizer, and change agent Bernice Johnson Reagon said, “If you’re in a coalition and you’re comfortable, you know it’s not a broad enough coalition.” The words serve as an important reminder for working to build solidarity. We must not center our own comfort, but remain open to the many unlikely collaborations that can result in change.

Summary

Michelle Gawerc writes, “By coming together and pooling resources, networks, and knowledge, coalitions allow for creating something larger and more ambitious than could be done as one group or organization . . .” (2019). It is possible to come together in similar ways within our feminist friendships, and it is our experience that these types of friendships are what can sustain us. Even after Kim and Sahana left their roles at the institution, they still co-labored with me (Elizabeth). I was applying for a job at a different institution which happened to be near where both Kim and Sahana lived. The night before my interview, Kim and Sahana met me at my hotel, brought a meal, and listened to the public presentation I would be giving the next day. They gave me important feedback—pointing out what to cut, remembering more powerful examples I could provide, and also providing me with lots of love and encouragement.

One thing that I am particularly thankful for from this night was Sahana and Kim helping me recraft my personal statement. They shared honestly that they did not think it was strong enough or fully captured how I approach prevention work. They asked me some probing questions, Sahana typed what I was saying, and they helped me distill it to a statement that accurately represents how I move in this work. It is the personal statement that I still use and holds tremendous value to me because it is not just a reflection of me, but a reflection of how people who speak truth into my life and witness me move in the work and know that they will hold me accountable to how I claim to move.

Postscript

The stories and examples shared across this chapter demonstrate our commitments to solidarity and coalition building in the service of eradicating GV. We hope you see the transformative power of this work and choose to join us in it.

Attributed to a lecture she gave at Southern Illinois University, the following words from Angela Davis continually inspire us to continue to stay in this work, “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” We hope that you resist the urgency to run full speed ahead and slow down to consider how you might like to join this work or continue the work you are currently doing to end GV. We have provided you with some prompts below to consider how you might employ friendship to actualize a PCF of attending to GV. Maybe grab some snacks and your friends and ponder these prompts together.

- What are some ways you see friendship as a form of resistance to oppression?

- How might you start the process of unlearning harmful and false narratives about GV?

- Who could hold you accountable to this unlearning?

- Who are or could be your co-laborers in this work?

- Are there daily practices that you can implement to resist oppression?

- What inspires you to do anti-oppression work?

- How might you provide encouragement and support to your co-laborers/friends?

We are so thankful you are here doing this work with us.

In Friendship,

Whitney & Elizabeth

Review Questions

Questions for Reflection

- How does gender violence intersect with other forms of discrimination (e.g., racial, economic, LGBTQIA+ identity), and how should colleges address these intersections in prevention efforts?

- How does college culture, including party culture, contribute to or perpetuate gender violence, and what can be done to challenge these norms? In what ways can gender violence undermine the academic, social, and emotional well-being of students, especially survivors?

- What are some ways that co-laboring with others can strengthen individuals as well as the larger movement to eradicate gender violence on campuses? Will you use any of the prompts given above to aid you in your own work against gender violence?

References

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373377

Anderson, K., Campbell, M., & Belcourt, C. (Eds.). (2018). Keetsahnak: Our missing and murdered Indigenous sisters (1st ed.). The University of Alberta Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781772123906

brown, a. m. (2017). Emergent strategy: Shaping change, changing worlds. AK Press.

Campbell, R., & Wasco, S. M. (2005). Understanding rape & sexual assault: 20 years of progress and future directions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(1), 127-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504268604

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Education Amendments 1972, 20 U.S.C. §§1681 – 1688.

Foster, M. H., Rohner, C. D., & Hildebrandt, K. (2019). Comprehensive prevention toolkit (V 2.0). Oregon Attorney General’s Sexual Assault Task Force. https://oregonsatf.org/comprehensive-prevention-toolkit

Freire, P. (2000/1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.; 30th anniversary ed.). Continuum.

Gawerc, M. I. (2019). Diverse social movement coalitions: Prospects and challenges. Sociology Compass, 14(1), e12760. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12760

Gibson, M. (2011, August 12). A brief history of women’s protests: Take back the night. Time. https://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0%2C28804%2C2088114_2087975_2087967%2C00.html

Grande, S. (2018). Refusing the university. In E. Tuck & K. Y. Yang (Eds.), Toward what justice? Describing dreams of justice in education (1st ed., pp. 47-65). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351240932

Hills, W., & Adams, B. (2023). You might be causing harm if . . . A poster campaign from the McCluskey Center for Violence Prevention Research and Education. Journal for Women and Gender Centers in Higher Education, 1(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.28953/2994-1350.1001

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Incite! Women of Color Against Violence (Ed.). (2016). Color of violence: the INCITE! anthology. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822373445

Koss, M. P., Gidycz, C. A., & Wisniewski, N. (1987). The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 55(2), 162-170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.162

Linder, C. (2018). Sexual violence on campus: Power-conscious approaches to awareness, prevention, and response. Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781787432284

Marine, S. B., & Lewis, R. (Eds.). (2020). Collaborating for change: Transforming cultures to end gender-based violence in higher education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190071820.001.0001

Marine, S. B., & Nicolazzo, Z. (2020). Campus sexual violence prevention educators’ use of gender in their work: A critical exploration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(21–22), 5005–5027. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517718543

Marine, S. B., Helfrich, G., & Randhawa, L. (2017). Gender-inclusive practices in campus women’s and gender centers: Benefits, challenges, and future prospects. Journal About Women in Higher Education, 10(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407882.2017.1280054

Rendón, L. I. (2009). Sentipensante (sensing/thinking) pedagogy: Educating for wholeness, social justice, and liberation. Stylus.

Samaritan Health Services (n.d.). Sarah’s place: A safe place to heal. https://samhealth.org/find-a-location/sarahs-place/

Sexual Assault Prevention and Awareness Center. (2018). For survivors by survivors. University of Michigan. https://sapac.umich.edu/article/survivors-survivors

Sulkowicz, E. (2014, May 15). My rapist is still on campus. Time. http://time.com/99780/campus-sexual-assault-emma-sulkowicz/

Syracuse University (n.d.). Take back the night. https://sexualrelationshipviolence.syr.edu/prevent/annual-events/take-back-the-night/

Taylor, K. Y. (Ed.). (2017). How we get free: Black feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Haymarket Books.

UN Women. (2018, December). Guidance note on campus violence prevention and response. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2019/Campus-violence%20note_guiding_principles.pdf

United Nations Population Fund. (2023). Gender-based violence. https://www.unfpa.org/gender-based-violence#readmore-expand

Wilder, C. S. (2014). Ebony and ivy: Race, slavery, and the troubled history of America’s universities. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Winnemucca, S. (1883). Life among the Piutes: Their wrongs and claims (M. T. P. Mann, Ed.). Cupples, Upham & Co.

World Bank Group. (2017). Sustainable development goals: Gender equality. Atlas of Sustainable Development Goals. https://datatopics.worldbank.org/sdgatlas/archive/2017/SDG-05-gender-equality.html

World Health Organization. (2024, March 25). Violence against women: Fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Further Learning

American Association of University Women. (n.d.). Policy recommendations: Campus sexual misconduct. https://www.aauw.org/resources/policy/campus-sexual-misconduct/

Gyimah-Brempong, A. (2024, July 17). Bernice Johnson Reagon, a founder of The Freedom Singers and Sweet Honey in the Rock, has died. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/07/17/1213897036/bernice-johnson-reagon-sweet-honey-in-the-rock-obituary

National Sexual Violence Resource Center. (2025, March 19). Tips for college campuses during SAAM 2025. https://www.nsvrc.org/blogs/saam/tips-college-campuses-during-saam-2025

Media Attributions

- 12568946385 © Howl Arts Collective is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 2.0 license

- 36922882543 © Duke University Archives is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) 2.0 license

- Christine_Blasey_Ford_swearing_in © United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Mattress_Performance_rules_of_engagement © Emma Sulkowicz is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 4.0 license