Exploring Gender-Based Violence and Reproductive Health Access in Crisis

Kamalaveni Veni

Abstract

Learning Outcomes

- Students will describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender violence and challenges in accessing reproductive health services

- Students will describe strategies to strengthen resilient reproductive health systems

- Students will develop recommendations to increase the resilience of health care and minimize the need for reproductive health services in the face of future health emergencies and disease outbreaks

Reproductive Health Care, a Fundamental Human Right

Reproductive health is a fundamental human right recognized by international frameworks like the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Women’s sexual and reproductive health is intrinsically linked to multiple human rights, such as the right to life, freedom from torture, health, privacy, education, and non-discrimination. Both the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR) and the CEDAW have explicitly stated that women’s right to health encompasses their sexual and reproductive health (UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, 1999; UN Economic and Social Council, 2000). Violations of women’s sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and rights often stem from deeply in-built patriarchal beliefs that value women primarily for their reproductive abilities. These beliefs lead to early and closely spaced pregnancies, often to produce male offspring, causing severe health consequences, and women who are infertile frequently face ostracism and human rights violations.

Reproductive health directly impacts individuals’ autonomy over their bodies and life choices and intersects with various forms of Gender-Based Violence (GBV), significantly affecting overall physical health and social, economic, and psychological well-being. Moreover, cultural norms and societal expectations around reproduction often perpetuate harmful practices and stigmas, making policies and legal backing for reproductive rights essential. It is accepted globally that access to comprehensive reproductive health services empowers women specifically, to pursue education, careers, and personal goals, contributing to gender equality. The Beijing Platform for Action asserts that “the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence” (UN Women, 1995). Hence, reproductive health is a central issue for gender justice, and addressing reproductive health is crucial not only for providing necessary services but also for dismantling structural inequalities that perpetuate GBV, justifying its own chapter in discussions on gender justice.

What is Reproductive Justice?

The Reproductive Justice are the right to have a child, the right to not have a child, and the right to parent a child or children in safe and healthy environments. Reproductive justice is the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have or not have children as desired, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities. But pandemics often lead to breakdowns of social infrastructures, compounding existing weaknesses and conflicts. Existing gender inequalities are worsened by pandemic situations; for example, increasing the exposure of children and women to harassment and sexual violence when they attempt to procure necessities such as water, food, and firewood (UN Population Fund, 2020b).

Access to Reproductive Health Care Services During the Pandemic and Measures Taken

The COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted reproductive health services worldwide, including contraception, abortion, maternal care, and support for gender-based violence survivors (Kumar et al., 2020). However, the extent and nature of these disruptions varied according to the socio-cultural structure of different societies. For instance, in India’s community-oriented society, reproductive health decisions are often influenced by family and community networks. During the pandemic, these structures sometimes reinforced barriers, such as limiting women’s autonomy in seeking abortion or contraceptive services and perpetuating stigma around reproductive health. At the same time, India’s collectivist model also enabled support systems through community health workers, self-help groups, and NGOs that stepped in to deliver essential services where formal healthcare was inaccessible (Kumar et al., 2020).

In contrast, in the United States, an individual-oriented society, access was shaped more by systemic healthcare inequalities than family or community control. Patients faced widespread delays in accessing contraception, STI and cancer screenings, and HPV vaccinations due to clinic closures and resource reallocation. Here, barriers were primarily institutional; related to insurance coverage, geographic disparities, and racial/ethnic health inequities. The pandemic resulted in significant delays in accessing essential reproductive health care, exacerbating existing health disparities and impacting overall health outcomes (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020).

Increased Vulnerability of Women During the Pandemic

UN Women (2024) emphasizes the harmful impact of violence against women on various aspects of health, including increased rates of depression, anxiety disorders, unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and HIV, compared to those not experiencing violence. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic intensified women’s vulnerabilities in India by disrupting reproductive choices and access to contraception. States with weaker socioeconomic conditions, such as Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Odisha, reported significant declines in contraceptive use despite unchanged fertility preferences, exposing women to unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions. In contrast, wealthier states like Punjab, Delhi, and Tamil Nadu, and moderately developed Arunachal Pradesh, showed increased contraceptive use, likely due to stronger health infrastructure. These divergent patterns reveal how socioeconomic contexts shape reproductive autonomy. Ultimately, the pandemic widened regional inequalities, with women in poorer states bearing a disproportionate reproductive health burden (Rahman et al., 2024). Another example is that, despite the Centre for Disease Control’s removal of language suggesting delays in non-urgent visits and “elective” procedures, there was a dramatic decline in patients seeking reproductive healthcare (Weigel et al., 2020). The pandemic’s disruptions in supply chains contributed to an estimated 2.7 million unplanned pregnancies and 1.2 million unsafe abortions in its first year. Moreover, 35% and 21% of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) clinics closed in the U.S. South and Midwest, respectively. A decrease in STI testing was reported across multiple countries, including Jordan, Thailand, and Uganda, with 95% of community STI testing clinics in Central Asia and Europe reducing testing. In the U.S., prescriptions for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) dropped by 80%, while follow-up care for vulnerable women in South Africa also declined (Singh et al., 2023; VanBenschoten et al., 2022). This statistic highlights the pervasive nature of gender-based violence and the urgent need for collective action in a post-pandemic world.

Lockdowns, social distancing, clinic closures, and quarantine measures during the COVID-19 pandemic confined individuals to their homes, often trapping women with their abusers. This isolation hindered victims’ ability to seek support or escape abusive situations, leading to a significant increase in the risk of serious psychological consequences, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Brooks et al., 2020; Hawryluck et al., 2004; Reynolds et al., 2008). Furthermore, quarantine measures coincided with a surge in cases of gender-based violence (GBV), which often went unaddressed (Usher et al., 2020). GBV encompasses sexual, physical, and emotional violence, as well as neglect or deprivation, targeting individuals based on their gender (UN Women, 2020).

Pandemics exacerbate violence against women and children (VAW/C) through multiple direct and indirect pathways, including economic insecurity, social isolation, reduced access to health services, and heightened instability, underscoring the urgent need for gender-responsive policy interventions (Peterman et al., 2020). Job loss and financial stress made women more vulnerable, with the National Commission for Women (NCW) in India reporting a twofold increase in gender violence cases (Chandra, 2020). Lockdowns disrupted access to essential support services, including hotlines, shelters, and counselling, making it difficult for women to seek help or prompting fears about leaving their homes. This heightened their susceptibility to gender-based violence (John et al., 2020). Alcohol and substance abuse by partners, societal tolerance of violence, previous abusive relationships, threats of harm, and the lack of essential health services, including contraception and abortion, further intensified the incidence of GBV during the pandemic (Ostadtaghizadeh et al., 2023).

Women from marginalized communities, including those with disabilities, LGBTQIA+ individuals, refugees, and migrants, faced heightened vulnerabilities in accessing support services. The multifaceted barriers to contraceptive care during the pandemic severely impacted reproductive autonomy and raised concerns about potential increases in unintended pregnancies (Diamond-Smith et al., 2021).

Barriers to Reproductive Healthcare Access During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened existing disparities and emerged as barrier to women’s reproductive healthcare, underscoring the critical need for reproductive justice. Disruptions in services, economic instability, and social distancing measures significantly restricted women’s access to reproductive healthcare when they needed it most (Chandra, 2020). Tam et al. (2024) found that essential services, including antepartum, intrapartum, postpartum care, abortion, and sexual health services, were severely impacted, even in nations with universal healthcare systems. Financial hardships compounded these issues, as many women struggled to afford maternal care, worsened by poverty and food insecurity (Adelekan et al., 2024). During the COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria, women and adolescent girls faced significant barriers in accessing conventional sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, leading many to rely on alternative healthcare sources, such as pharmacies, traditional healers, or informal networks, to meet their reproductive health needs (Adelekan et al., 2024). For example, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria, access to maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) services was hindered by multiple barriers, including fear of infection, transportation difficulties, shortages of PPE and medical staff, and long hospital waiting times (Akaba et al., 2022). Taken together, these layered barriers highlight how the pandemic not only restricted healthcare access but also reinforced the urgent need for reproductive justice (Adelekan et al., 2024; Tam et al., 2024).

Challenges of Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services During Pandemic

- Fear of being tested and found to be COVID-19 positive

- Distance and transportation difficulty

- Financial constraint

- Restriction of movement

- Long waiting time at health facility’

- Fear of contracting COVID-19

- Health workers attending to limited number of people

- Harassment by uniformed men

- Stigmatization of unmarried youth who seek family planning

Source: Adelekan et al., 2024. Content based on Fig.1 licensed under a Creative Commons License 4.0 International

Disparities in Access to Contraceptives

The COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted access to essential reproductive health services, including contraception and abortion care, leaving many without critical healthcare. Lockdown measures halted manufacturing processes, causing contraceptive shortages (International Planned Parenthood Federation, 2020). The Guttmacher Institute’s analysis revealed the far-reaching consequences: a 10% reduction in sexual and reproductive health services could result in an additional 15.4 million unintended pregnancies, over 3.3 million unsafe abortions, and 28,000 maternal deaths globally (Krishna, 2021). In India, the Foundation for Reproductive Health Services India (FRHS India) forecasted significant setbacks in contraceptive access, predicting negative outcomes such as unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and maternal deaths. They outlined three scenarios to assess the pandemic’s impact: the Best Case projected that 24.55 million couples would struggle to access contraceptives by mid-2020 if services resumed quickly; the Likely Case anticipated 25.63 million couples would be affected by September 2020; and the Worst Case estimated that 27.18 million couples would face challenges due to the slow resumption of services. These figures demonstrate the importance of maintaining uninterrupted access to family planning during crises (FRHS India, 2020).

The pandemic also intensified issues of gender-based violence, particularly intimate partner violence. Many women faced reproductive coercion, where partners refused or sabotaged contraception, limiting women’s reproductive autonomy. Over 23% of women reported being unable to refuse sex (UN Population Fund, 2020a; Kumler, 2022). Additionally, Padez Vieira et al. (2022) found that pregnant women in Portugal experienced heightened depression during the lockdown, reflecting the broader mental health impact of restricted reproductive services. The barriers to contraception and reproductive health services during the pandemic highlight the urgent need for flexible, accessible options during crises. The denial of reproductive rights emphasizes the importance of proactive policies that protect women’s health and autonomy in future emergencies.

Increasing Maternal Mortality in the Wake of Health Service Disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed deep gaps in maternal health outcomes, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. Systemic inequities, such as racism and inadequate healthcare access, contributed to higher rates of maternal mortality and morbidity. Lockdown restrictions, economic hardships, and travel bans disrupted the distribution of reproductive health products and contraceptive services (Church et al., 2020). In India, these interruptions severely impacted institutional deliveries, with media reports from states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar showing a reduction in institutional deliveries, forcing many women to opt for home births (Motihar, 2020).

Mathematical models from the Global Financing Facility (GFF) indicated that disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to a 40% increase in child mortality and a 52% rise in maternal mortality (Motihar, 2020). The scoping review by Kotlar et al. (2021) examines the pandemic’s direct and indirect effects on maternal and perinatal health, analyzing 95 studies. It highlights increased risks for pregnant individuals, such as mental health challenges and socioeconomic disparities. The fear of contracting the virus has discouraged women from seeking maternal care, leading to decreased institutional deliveries, which are crucial for reducing maternal mortality. The authors emphasized the need for stronger healthcare infrastructure and targeted resources to address these disparities. Addressing these issues is vital for advancing reproductive justice and ensuring equitable access to maternal health services during public health crises.

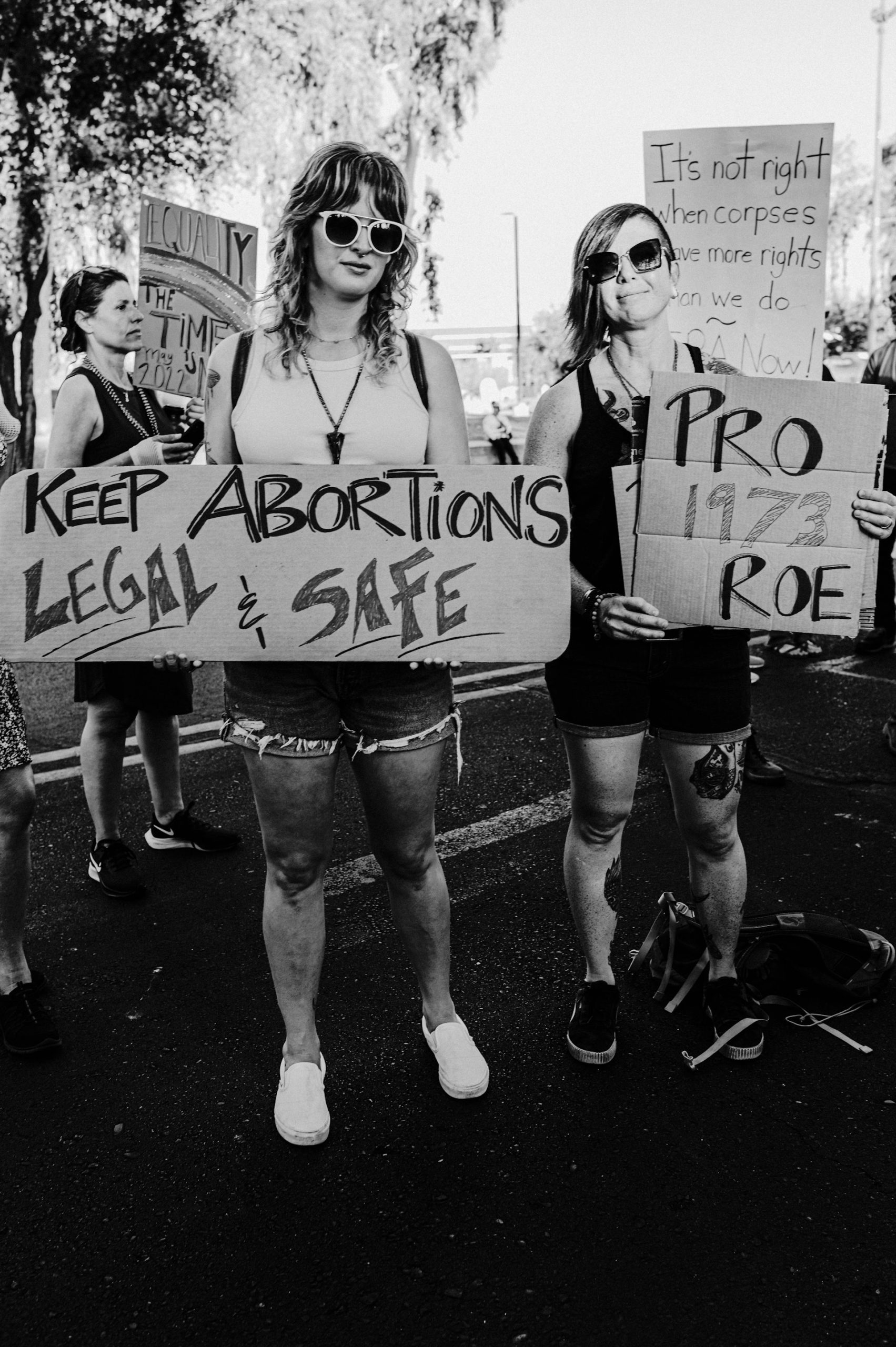

Intersection of Gender Violence and Abortion Rights: A Fight for Reproductive Autonomy

The connection between gender-based violence (GBV) and abortion access reveals significant challenges in safeguarding women’s reproductive rights. GBV, including intimate partner violence and sexual assault, often leads to unintended pregnancies, compelling survivors to seek abortions. However, restrictive laws, stigma, and insufficient healthcare services frequently hinder access to safe and legal abortion services, pushing women toward unsafe alternatives that jeopardize their health and well-being.

The right to abortion is intertwined with several fundamental human rights, including the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment (UN General Assembly, 1984). Additionally, access to abortion is vital to the broader framework of sexual and reproductive health, education, and information (UN Population Fund, 1994; UN Women, 1995). The CEDAW Committee recognizes the criminalization of abortions and forced continuation of pregnancies as forms of gender-based violence and discrimination, highlighting how these violations infringe upon women’s rights under CEDAW. Such restrictions force women into unsafe abortions and restrict their autonomy over their physical and mental health, further contributing to the underreporting of sexual violence.

The Supreme Court of India in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) and Anr v Union of India and Ors (2017) affirmed that “[t]he intersection between one’s mental integrity and privacy entitles the individual to freedom of self-determination,” particularly regarding gender identity, reproduction, and procreation. Similarly, the Bombay High Court emphasized that forcing a woman to continue an unwanted pregnancy “represents a violation of the woman’s bodily integrity and aggravates her mental trauma” (High Court on Its Own Motion v. State of Maharashtra, 2017 as cited in Chandra et al., 2019, p. 188). Restrictions on abortion access, exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, heightened these inequities, with many governments exploiting public health measures to further limit services, forcing women to seek unsafe alternatives and undermining their reproductive autonomy.

Learning Activity:

Interactive Case Study Analysis on Gender Violence and Reproductive Health During COVID-19

Case Study 1: Gender Violence in India During COVID-19. During the COVID-19 lockdown in India, the National Commission for Women recorded a twofold increase in gender violence cases. Financial stress and confinement with abusers exacerbated the situation. Discuss the challenges women faced in seeking help and propose strategies to improve support services during such crises.

Case Study 2: Reproductive Health Challenges in the United States. In the US, over half of clinics cancelled or postponed contraceptive visits during the pandemic, significantly impacting access to reproductive health services. Analyze the barriers to accessing these services and recommend solutions to ensure continuity of care in future pandemics.

Case Study 3: Impact on Marginalized Communities in Nigeria. In Nigeria, economic hardships and law enforcement harassment prevented pregnant women from accessing maternal healthcare. Discuss the specific challenges faced by marginalized communities and suggest measures to address these disparities.

Case Study 4: Global Disruptions in Contraceptive Access. The COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant decline in contraceptive access globally, with anticipated shortages and increased unintended pregnancies. Evaluate the impact on women’s health and propose strategies to mitigate such disruptions in future health emergencies.

Illustrations of Disruption in Abortion Services During COVID-19

The COVID-19 lockdown in India severely impacted access to safe abortions, as illustrated by the story of Kiran, a 20-year-old college student in Delhi. Kiran, who found out she was pregnant in May 2020, initially tried to terminate the pregnancy using abortion pills, but they were ineffective. As her only option was a surgical abortion, Kiran faced significant challenges due to the lockdown, which restricted travel and limited hospital services to essential care only. Despite contraception and abortion being classified as essential, many hospitals shut down outpatient departments and cancelled elective surgeries, complicating access to reproductive health services (Rao, 2020).

Kiran’s struggle is part of a broader issue, as research indicates that the lockdown compromised an estimated 1.85 million abortions in India. Women were pushed towards unsafe abortions or surgical procedures due to delayed access to medical abortions. Public health advocates and doctors reported an increase in calls from women seeking help for abortions but being turned away from hospitals or facing delays, particularly affecting poorer women and those in rural areas. Kiran’s case was eventually resolved with the help of the Medical Support Group, a team of public health professionals who assisted her in finding a doctor for a safe abortion. This case highlights the urgent need for policy changes, such as allowing medical abortions via telemedicine and strengthening referral systems for abortion services, to ensure women’s reproductive health needs are met during crises (Rao, 2020).

During India’s lockdown, despite abortion being classified as an essential service, many women struggled to access safe medical care due to restricted transportation, limited healthcare services, and movement restrictions. Experts warned that this could lead women to use unsafe methods or continue with unwanted pregnancies. The stigma surrounding abortion further complicated the access.

A comprehensive review by Ochola et al. (2023) highlighted the significant interruptions in access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services and the harmful impact on the well-being of women of reproductive age during the pandemic. Loss of income and employment opportunities resulted in the inability to afford healthcare costs, further reducing access to maternal healthcare services. Additionally, de-prioritization of services during the pandemic limited access to maternal healthcare, particularly among women from neighbouring communities due to entry restrictions and limited public transport. While some areas with unrestricted access to reproductive health services have observed an increase in family planning uptake among adolescents, travel restrictions and lockdown measures have likely contributed to the reduction in attendance at post-abortion care services. Adolescents emerge as a vulnerable group, with higher maternal death rates and limited access to abortion care. The increase in gender-based violence (GBV) has been attributed to economic stressors, lack of privacy, and movement restrictions during the lockdown. Stay-at-home orders exacerbated the situation, leading to increased reports of GBV cases.

Reproductive Healthcare Inequities for Marginalized Communities: Addressing Gaps for Transgender and Queer Individuals

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing barriers to reproductive healthcare, affecting contraception, prenatal care, abortion, and STI testing, with marginalized populations like LGBTQIA+ individuals, low-income groups, lower caste people, people of color, and rural communities facing the brunt of these challenges (Diamond-Smith et al., 2021; John et al., 2020). Lockdowns and healthcare interruptions further deepened disparities, although telemedicine emerged as a solution to provide reproductive healthcare services remotely. However, this method remained inaccessible to many due to the digital divide, which disproportionately affected marginalized communities (MacLean, 2021).

While women’s reproductive rights have gained increasing attention globally, including in India and the USA, transgender reproductive rights remain largely overlooked.

Raj Yadav and Aditi Jain (2021) analyze the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, emphasizing its exclusion of transgender individuals, especially transgender men, from abortion rights. The paper critiques India’s abortion laws for catering only to cisgender women, ignoring the unique reproductive needs of transgender people. The authors highlight legal conflicts between the MTP Act and other laws like the Pre‐conception and Pre‐Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act and Protection of Child from Sexual Offenses (POCSO) Act (Ministry of Women and Child Development, n.d), while also discussing economic barriers. They advocate for legal reform to include transgender rights in reproductive healthcare, addressing both social and medical challenges (Shendge et al., 2024).

A literature review on transgender men’s reproductive health by MacLean (2021) reveals feelings of invisibility and isolation during pregnancy due to gendered perinatal care. The lack of gender-affirming environments and experienced providers contributes to care avoidance and discrimination. The reproductive rights of transgender individuals remain overlooked in medical curricula and legal frameworks, particularly in India, where LGBTQIA+ communities are ostracized and invisibilized (MacLean, 2021). More research is essential to improve their reproductive healthcare experiences. Similarly, Lunde et al. (2021) found that transgender and non-binary individuals globally face barriers when seeking healthcare services, due to practitioners’ lack of knowledge. Rodriguez-Wallberg et al. (2023) stressed the importance of researching fertility preservation and family planning options for the transgender community.

This scoping review investigates the barriers faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals in accessing abortion care and pregnancy options counselling. The study reveals significant discrimination and healthcare avoidance, leading to unsafe abortions and adverse health outcomes. The authors advocate for gender-inclusive healthcare services and further research to address the unique needs of this marginalized community (Bowler et al., 2023). The entrenched legal frameworks defining reproductive rights through a cisgender lens underscore the need for more inclusive policies. To address these issues, documenting the lived experiences of marginalized communities is essential to sensitizing the medical field and advancing reproductive justice (Stephenson et al., 2017).

Essential Reproductive Health Care Services to Resist Gender Violence

The World Bank (2020) emphasizes the importance of maintaining essential health services during the pandemic. The pandemic presented not only a direct threat to health but also significant risks of indirect morbidity and mortality when essential health services were disrupted. Supply-side challenges included the diversion of medical personnel to COVID-19 response, overwhelmed health facilities, and disruptions in global supply chains for essential supplies. Demand-side factors included reduced use of essential services due to lockdowns, financial constraints, and fear of COVID-19 exposure. Past epidemics like Ebola and SARS have also shown declines in healthcare utilization, particularly for maternal and child health services, during crises. Preserving essential health services is crucial for safeguarding the health and well-being of mothers and children, especially during economic downturns and pandemics like COVID-19. Policymakers must incorporate SRH into emergency preparedness and response planning to mitigate indirect impacts in future outbreaks (Singh et al., 2023).

Summary

Reproductive health is an essential component of human rights and is intricately linked to gender justice. The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified pre-existing inequalities in access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, disproportionately affecting marginalized populations and increasing incidences of gender-based violence (GBV). During the pandemic, lockdowns and clinic closures disrupted crucial services such as contraception, abortion, and STI testing; exacerbating vulnerabilities for women, especially those from disadvantaged communities. This crisis underscored the pressing need for resilient healthcare systems equipped to address reproductive health needs while also emphasizing the importance of robust policies that prioritize reproductive justice. Such policies should ensure that all individuals can exercise bodily autonomy and make informed choices regarding their reproductive health. As we move forward, it is imperative to strengthen healthcare infrastructures, broaden access to SRH services, and confront the structural inequalities that perpetuate both GBV and disparities in reproductive health access.

A comprehensive approach to reproductive justice must include the needs of all populations, particularly LGBTQIA+ individuals and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Future public health strategies should integrate sexual and reproductive health services into emergency preparedness and response plans, guaranteeing that every individual can access necessary care during crises. By advocating for reproductive rights and equitable healthcare access, we can build a more just and inclusive society. Ultimately, ensuring reproductive justice is not only vital for empowering women but also essential for advancing gender equality globally. As we reflect on the lessons learned from the pandemic, a collective commitment to addressing these inequities will be crucial in shaping a healthier and more equitable future for all.

Review Questions

Questions for Reflection

- In what ways did epidemiological measures during the pandemic contribute to increased gender violence, limit access to support services for victims, and enable severe physical and psychological injuries?

- What are some disparities in reproductive health care, including access to contraception and disruptive health care systems, that impacted marginalized populations during the pandemic, leading to unintended pregnancies and maternal mortality?

- How have epidemics disrupted essential health services, particularly maternal and birth care? Describe some structural disparities and explain the importance of protecting these services to ensure maternal and child health.

References

Adelekan, B., Ikuteyijo, L., Goldson, E., Abubakar, Z., Adepoju, O., Oyedun, O., Adebayo, G., Dasogot, A., Mueller, U., & Fatusi, A. O. (2024). When one door closes: A qualitative exploration of women’s experiences of access to sexual and reproductive health services during the COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15848-9

Akaba, G. O., Dirisu, O., Okunade, K. S., Adams, E., Ohioghame, J., Obikeze, O. O., Izuka, E., Sulieman, M., & Edeh, M. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of access to maternal, newborn and child health services during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria: Findings from a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 22, 611. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07996-2

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2020). Joint statement on abortion access during the COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2020/03/joint-statement-on-abortion-access-during-the-covid-19-outbreak

Bowler, S., Vallury, K., & Sofija, E. (2023). Understanding the experiences and needs of LGBTIQA+ individuals when accessing abortion care and pregnancy options counselling: A scoping review. BMJ Sexual Reproduction Health, 49(3), 192-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2022-201692

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912-920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Chandra, A., Satish, M., & the Center for Reproductive Rights. (2019). Securing reproductive justice in India: A casebook. Center for Reproductive Rights and Centre for Constitutional Law, Policy and Governance, National Law University, Delhi. https://www.nls.ac.in/publications/securing-reproductive-justice-in-india-a-casebook/

Chandra, J. (2020, April 3). National Commission for Women records a rise in complaints since the start of lockdown. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/national-commission-for-women-records-a-rise-in-complaints-since-the-start-of-lockdown/article31241492.ece

Church, K., Gassner, J., Elliott, M., Clark, E., Hossain, A., & Van Lith, L. M. (2020). Poor women’s reproductive health and family planning challenges and needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Population Council. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2326&context=departments_sbsr-rh

Diamond-Smith, N., Logan, R., Marshall, C., Corbetta-Rastelli, C., Gutierrez, S., Adler, A., & Kerns, J. (2021). COVID-19’s impact on contraception experiences: Exacerbation of structural inequities in women’s health. Contraception, 104(6), 600–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2021.08.011

Foundation for Reproductive Health Services India. (2020, May). Impact of COVID-19 on India’s family planning program [Policy brief]. https://www.frhsi.org.in/images/impact-of-covid-19-on-indias-family-planning-program-policy-brief.pdf

Hawryluck, L., Gold, W. L., Robinson, S., Pogorski, S., Galea, S., & Styra, R. (2004). SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(7), 1206-1212. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1007.030703

International Planned Parenthood Federation. (2020, April 9). COVID-19 pandemic cuts access to sexual and reproductive healthcare for women around the world. https://www.ippf.org/news/covid-19-pandemic-cuts-access-sexual-and-reproductive-healthcare-women-around-world

John, N., Casey, S. E., Carino, G., & McGovern, T. (2020). Lessons never learned: Crisis and gender-based violence. Developing World Bioethics, 20(2), 65-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12261

Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Anr v. Union of India & Ors, (2017) 10 SCC 1; AIR 2017 SC 4161.

Kotlar, B., Gerson, E. M., Petrillo, S., Langer, A., & Tiemeier, H. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: A scoping review. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6

Krishna, U. R. (2021). Reproductive health during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India, 71(S1), S7-S11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-021-01546-2

Kumar, M., Daly, M., De Plecker, E., Jamet, C., McRae, M., Markham, A., & Batista, C. (2020). Now is the time: A call for increased access to contraception and safe abortion care during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Global Health, 5(7), e003175. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003175

Kumler, A. (2022, October 12). Reproductive autonomy: The goal in family planning. NewsSecurityBeat. https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2022/10/reproductive-autonomy-goal-family-planning/

Lunde, C. E., Spigel, R., Gordon, C. M., & Sieberg, C. B. (2021). Beyond the binary: Sexual and reproductive health considerations for transgender and gender expansive adolescents. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3, 670919. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.670919

MacLean, L. R.-D. (2021). Preconception, pregnancy, birthing, and lactation needs of transgender men. Nursing for Women’s Health, 25(2), 129-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2021.01.006

Ministry of Women and Child Development. (n.d.). Legislations. Government of India. https://wcd.gov.in/documents/legislations

Motihar, R. (2020, June 25). The impact of COVID-19 on reproductive health services. IDR Online. https://idronline.org/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-reproductive-health-services/

Ochola, E., Andhavarapu, M., Sun, P., Mohiddin, A., Ferdinand, O., & Temmerman, M. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries: A rapid review. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2023.2203001

Ostadtaghizadeh, A., Zarei, M., & Saniee, N. (2023). Gender-based violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic: Recommendations for the future. BMC Women’s Health, 23, 219. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02372-6

Padez Vieira, F., Mesquita Reis, J., Figueiredo, P. R., Lopes, P., João Nascimento, M., Marques, C., & Caldeira da Silva, P. (2022). Depression among Portuguese pregnant women during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross sectional study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 26, 1779–1789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03466-7

Peterman, A., Potts, A., O’Donnell, M., Thompson, K., Shah, N., Oertelt-Prigione, S., & van Gelder, N. (2020). Pandemics and violence against women and children. Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/pandemics-and-violence-against-women-and-children

Rahman, M. M., Pradhan, M. R., Ghosh, M. K., & Rahman, M. M. (2024). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on fertility behaviour in Indian states: Evidence from the National Family Health Survey (2019/21). PLOS One, 19(12), e0314800. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314800

Rao, M. (2020, July 12). The women who can’t get an abortion in lockdown. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-53345975

Reynolds, D. L., Garay, J. R., Deamond, S. L., Moran, M. K., Gold, W., & Styra, R. (2008). Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiology & Infection, 136(7), 997-1007. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268807009156

Rodriguez-Wallberg, K., Obedin-Maliver, J., Taylor, B., Van Mello, N., Tilleman, K., & Nahata, L. (2023). Reproductive health in transgender and gender diverse individuals: A narrative review to guide clinical care and international guidelines. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2035883

Shendge, A., Royal, A., Dange, A., & Kumar, V. (2024). Medical termination of pregnancy (Amendment) Act 2021: From the lenses of LGBTQIA+ community in India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 13(12), 5459–5464. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_818_24

Singh, L., Abbas, S. M., Roberts, B., Thompson, N., & Singh, N. S. (2023). A systematic review of the indirect impacts of COVID-19 on sexual and reproductive health services and outcomes in humanitarian settings. BMJ Global Health, 8(11), e013477. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013477

Stephenson, R., Riley, E., Rogers, E., Suarez, N., Metheny, N., Senda, J., Saylor, K. M., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2017). The sexual health of transgender men: A scoping review. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4-5), 424-445. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1271863

Sully, E. A., Biddlecom, A., Darroch, J. E., Riley, T., Ashford, L. S. Lince-Deroche, N., Firestein, L., & Murro, R., (2020, July). Adding it up: Inveting in sexual and reproductive health 2019. Guttmacher Institute. https://doi.org/10.1363/2020.31593

Tam, M. W., Davis, V. H., Ahluwalia, M., Lee, R. S., & Ross, L. E. (2024). Impact of COVID-19 on access to and delivery of sexual and reproductive healthcare services in countries with universal healthcare systems: A systematic review. PLOS One, 19(2), e0294744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294744

UN Women. (1995, September). Beijing declaration and platform for action. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform/

UN Women. (2020). The shadow pandemic: Violence against women during COVID-19. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19

UN Women. (2024, November 25). Facts and figures: Ending violence against women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures

United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. (1999). Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. General recommendation no. 24, article 12 of the convention (women and health). https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/recommendations/recomm.htm#recom24

United Nations Economic and Social Council. (2000, August 11). General comment no 14 on the highest attainable standard of health (2000). The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (E/C.12/2000/4). https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/ec1220004-general-comment-no-14-highest-attainable

United Nations General Assembly. (1984). Convention against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (A/RES/39/46). https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/cat.pdf

United Nations Population Fund. (1994). International conference on population and development programme of action. https://www.unfpa.org/icpd

United Nations Population Fund. (2020a). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family planning and ending gender-based violence, female genital mutilation and child marriage. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/impact-covid-19-pandemic-family-planning-and-ending-gender-based-violence-female-genital

United Nations Population Fund. (2020b). Sexual and reproductive health and rights: An essential element of universal health coverage. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/SRHR_an_essential_element_of_UHC_2020_online.pdf

Usher, K., Bhullar, N., Durkin, J., Gyamfi, N., & Jackson, D. (2020). Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 549-552. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12735

VanBenschoten, H., Kuganantham, H., Larsson, E. C., Endler, M., Thorson, A., Gemzell-Danielsson, K., Hanson, C., Ganatra, B., Ali, M., & Cleeve, A. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to and utilisation of services for sexual and reproductive health: A scoping review. BMJ Global Health, 7(10), e009594. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009594

Weigel, G., Salganicoff, A., & Ranji, U. (2020, June 24). Potential impacts of delaying “non-essential” reproductive health care. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/potential-impacts-of-delaying-non-essential-reproductive-health-care/

World Bank Group Global Financing Facility. (2020, May 8). Country briefs: Preserve essential health services during COVID-19 pandemic [Brief/Fact sheet]. https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/country-briefs-preserve-essential-health-services-during-covid-19-pandemic

Yadav, R., & Jain, A. (2023). Ensuring reproductive freedom: A study of the MTP Act and transgender communities’ access to abortion. International Journal of Science and Research, 12(2), 828-832. https://www.ijsr.net/getabstract.php?paperid=SR23214101924

Further Learning

Human Rights Watch. (2023, March 31). Sex testing rules harm women athletes. [News release]. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/03/31/sex-testing-rules-harm-women-athletes

Snelson, F. (2023, March 23). The story of England’s first women’s team: Subversion, scandal, & skill. PlanetFootball. https://www.planetfootball.com/nostalgia/the-story-of-great-britains-first-womens-football-team-subversion-scandal-skill

Vox. (2019, June 29). The problem with sex testing in sports [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiCftTLUzCI

Media Attributions

- ethan-gregory-dodge-BFkNyQ7JvD8-unsplash © Ethan Gregory Dodge is licensed under an Unsplash license

- lauren-mitchell-X1Z5kZRBrP4-unsplash © Lauren Mitchell is licensed under an Unsplash license

- gayatri-malhotra-JbAOhfWum1s-unsplash © Gayatri Malhotra is licensed under an Unsplash license

- rhsc-m206W8HQJAQ-unsplash © Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition is licensed under an Unsplash license

- 53574326983 © Fibonacci Blue is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 2.0 license

- 51547057589 © John Ramspott is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) 2.0 license