Section 3: Things that are likely to change

This section covers many ideas similar to those in section two with an important difference, these concepts are likely to change. At the core of each idea are things that won’t change.

3.1 Semiotics

Semiotics refers to the study of symbol systems. This is independent of information theory, which considers the capacity of a channel and the capacity of a message to overcome entropy or noise in the channel.[1] Semiotics is concerned with meaning. We can think of meaning on three levels: semantic (did the communicators reach agreement about meaning), pragmatic (did the meaning coordinate action), and alterity (what meanings were precluded by the presentation of the sign). An important problem comes in the degree to which meaning can be communicated at all. Communication is constitutive.[2] The following statement is rich with mysticism: you are the meaning that you use and are used by. This does not mean that you are dominated by language or that you have no decisions, but that meaning is a central dimension of human existence.

Communication is not sending meaning packages through tubes to each other. Meaning is constantly produced between people. This does not mean that there is no agreement, but that the slippages between potential agreements produce many productive errors. Network research suggests that over-convergence is a major problem, if messages are too similar people distrust them.[3] Further, ongoing message divergence is evidence of error correction, which could itself evidence of an effective system. People make meanings, those meanings are unstable, and this instability is productive.

3.1.1 Signs

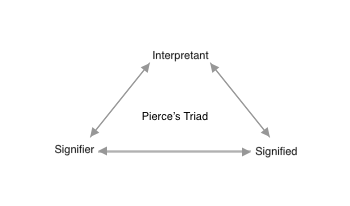

The sign is the basic unit of semiotic theory. It is important to understand that signs are not stable. For Charles Sanders Pierce, the sign is triadic:

The object, the interpretant (the sign that is created in the mind of the receiver), and the sign are all in relationship.[4] Although the object is very much involved, but there is no objective basis for the sign, the sign itself and the sign produced by the sign are equally as important. Notice that the idea in the mind that matters in this model is that which exists in the mind of the receiver, not the sender. This model takes the intent of the speaker out of the center of the model. It does not matter what you intended if that cannot be produced as an interpretant.

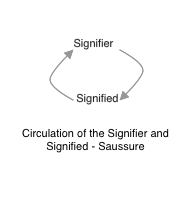

Sassure’s model has a slightly less complex circulation.[5]

In this context, the thing (signified) is imperfectly represented and in circulation with the signifier (the label). The signified can be almost anything, often including another sign. The signifier is constantly being loaded with additional content.

What should be clear in both models is that meaning is continuously in circulation. The ways that we manage this constantly shifting meaning are many and likely the reasons why you will be employed after college. A key distinction made by Saussure that is helpful: langue and parole. Langue refers to the formal code, while parole refers to everyday speech. This is why we teach multiple methods for determining what meanings are at any given time. There is no encyclopedia or dictionary for symbol systems, corporations are constantly searching for the ways that terms and ideas function at any given time.

3.1.2 Typology of Signs

Pierce has three kinds of signs:[6]

Icon: signs that look like things.

Index: representations of action (such as smoke is a sign for fire).

Symbol: an entirely artificial system (such as the text of this book).

Notice that these categories are not absolutely clear. Smoke may be a probabilistic sign of fire, but it can also be a symbol for something being hot. It is less likely that you thought that smoke was a sign of a smoke monster, a creature made of smoke. It is the probability that the sign is what you were thinking that is what makes it function. You see smoke and reasonably guess fire. This is the core of abductive reasoning, we make a number of probable assumptions and work as if they are confirmed. It should be apparent at this point that there are not easy logical answers or transcendental operators.

These signs can help you make decisions about how particular messages work. An iconic sign that includes an image may function quite differently than a description of that sign. You can see that in each of these contexts all three dimensions of a sign are always subtly shifting. Consider the iconic representation of a telephone, to some degree that is still most likely presented with an older handset on a desk cradle. Younger people may be less familiar with such a phone, however the icon for phone will likely remain the handset and cradle for some time.

Symbolic signs can be incredibly dense. This book is made up of almost entirely symbolic signs in the form of written text. Unless you are already quite a reader, the symbols in this book would be difficult to guess. Feelings and sensations can be exceptionally difficult to represent with a sign, often hinging on multiple signs that encircle what would be described.

3.1.2 Codes

It is important to keep in mind that Saussure contended that meaning existed in opposition. We know what a sign means through it’s relation to other signs.[7] Codes are organized systems of signs. Some codes are more sophisticated than others. People use codes all the time, they are not particularly special. For Roland Barthes the role of codes, as myths, allows the interposition of codes and facts:

In fact, what allows the reader to consume myth innocently is that he does not see it as a semiological system but as an inductive one. Where there is only an equivalence, he sees a kind of causal process: the signifier and the signified have, in his eyes, a natural relationship. This confusion can be expressed otherwise: any semiological system is a system of values; now the myth-consumer takes the signification for a system of facts: myth is read as a factual system, whereas it is but a semiological system.[8]

Symbolic forms have the status of facts, like marriage proposals, names for ships or highways, and statements of financial data, among many other possible codes. This is why semiotic critique is so useful, at each stage of recirculation the products of code become the facts that produce reality. It is not required that one fully establish all of the grounds on which they might argue, this would be boring and wasteful. You operate using the assumptions inherent in a code as if those assumptions were facts.

It would also make sense that the highly iterated symbolic signs would begin to play an increasing role in society. Once someone has gone to all the necessary trouble to learn a sign and all the content that comes with it, the deployment of that sign again in more sophisticated systems would be efficient. In a highly complex system of signs, the ways in which the meanings of certain signs might shift becomes an important topic of negotiation. This takes the form of a kind of meta-talk: you can identify it in many different kinds of communication. In relational communication, it can take the form of the “where do we stand” conversation with a dyadic partner; in political communication the discussion of the “narrative”

3.1.3 Ideograph

Special case of signs that have lost all content but still interpolate the social field. Examples of these special terms include freedom and the people. We all know that you are supposed to love freedom, but the meaning of freedom and any discussion of the internal dynamics of what might make someone more or less free are not up for political contestation. Likewise, the idea of the people is very important in many political cultures. The general will of regular folks is seen as excluded from what would be an elite conversation, which is then claimed and included by elites in the form of the will of “the people.” Measuring the will of the people is imperfect, there is no method to directly combine an understanding of the will of thousands of people. The term ideograph was developed by Michael Calvin McGee, it proposes that certain terms take on this special status where they can stitch together the social totality.[9] The key to studying these systems is to evaluate the use of the term presently (synchronically) and to juxtapose that with the development of the term over time (diachronically). This method can provide you some insight into how the term functions and the role it plays in the code of society. At the highest levels, certain signs can have powerful effects on the structure and meaning of a code, even moderating the function of multiple layers of other signifiers. There are many other signs like an ideograph that are very important – these are the core topics of your course work in Rhetorical Studies (should your program include Rhetoric).

3.1.4 Publics

Public sphere is a mistranslation of publicity which is a verb, not a noun: publicity is a process by which ideas become visible and circulate. Much of the thinking in this field is organized around Jurgen Habermas Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, a key work which proposed a theory that a rational, critical public sphere could emerge through the circulation of texts. This book is a rich starting point as Habermas is willing to sketch the historical, psychological, and sociological dimensions by which the pubic becomes possible. It is also important to note that even at the time of publication, he was not optimistic about the future of the public sphere.

Nancy Frasier’s classic “Rethinking the Public Sphere,” gets at the key problems with this account, with a particular emphasis on exclusion.[10] Women and minorities were excluded from the bourgeois realm of the public sphere. This did not mean that they did not communicate, but that they formed counter publics all along. The exclusions and rules that come along with the public sphere can become an oppressive ideology on their own. Frasier is clear that these counter publics are a structural element of the theory, they are not intrinsically positive: they simply are. Frasier makes four key points: inequality cannot be wished away, there is not a single public, excluding “private” issues misses much, and better models of the multiple interactions of publics offer a lot for understanding social change.

Along similar lines, Michael Warner has further explored counter publics as they form in discourse and through attention alone.[11] You can become a part of a public without giving a speech or wearing a campaign t-shirt: you join by paying attention. Ron Greene on the other hand has recuperated the centralizing functions of the public sphere as a sort of postal service: the public as an idea allows letters to find their addressees.[12] What if the public sphere is the process by which ideas are moved around, even if that process deeply flawed? The key idea here is that a public forms when those that could be addressed are exposed to a possible message.

This says nothing of the far older debate between theories of publics and masses. Publics are those who are engaged in some kind of deliberation while masses are a herd to be steered. It is also important to notice that publics in this formulation are asked to have an idea of themselves. Publics are a powerful form for the organization of everyday life, but the ways that publics are hailed into existence and organized are always changing. To this point these constructs are in continuous revision and discussion.

3.1.5 Argumentation

How we argue and how we evaluate arguments is constantly changing. Arguments are another special form of code. The idea of the syllogism is thousands of years old, but ultimately the form of the syllogism is only useful in cases where a clear formula in the context of a dialectical regime of truth is possible. What does that mean? The syllogism depends on the idea that there is a truth and that by ascertaining proper premises an accurate statement can be confirmed.

Consider this syllogism:

Dan is a person

People have opinions

Dan has opinions

Or to put in an abstract form:

Dan is a member of group A

All members of A have property B

Thus, Dan has property B

In terms of a structural logic, his operates through a right hand left hand movement that is also used in some computer programming languages. The problem with the syllogism is that it can only handle one operator at a time. What we find in the analysis of complex issues of policy or value is that there may be multiple contingent identities and relationships in any given argument system. You also may have noticed the implicit use of the idea of ‘all’ in the example –a further problem. How do we make arguments when identities are unclear or are in flux?

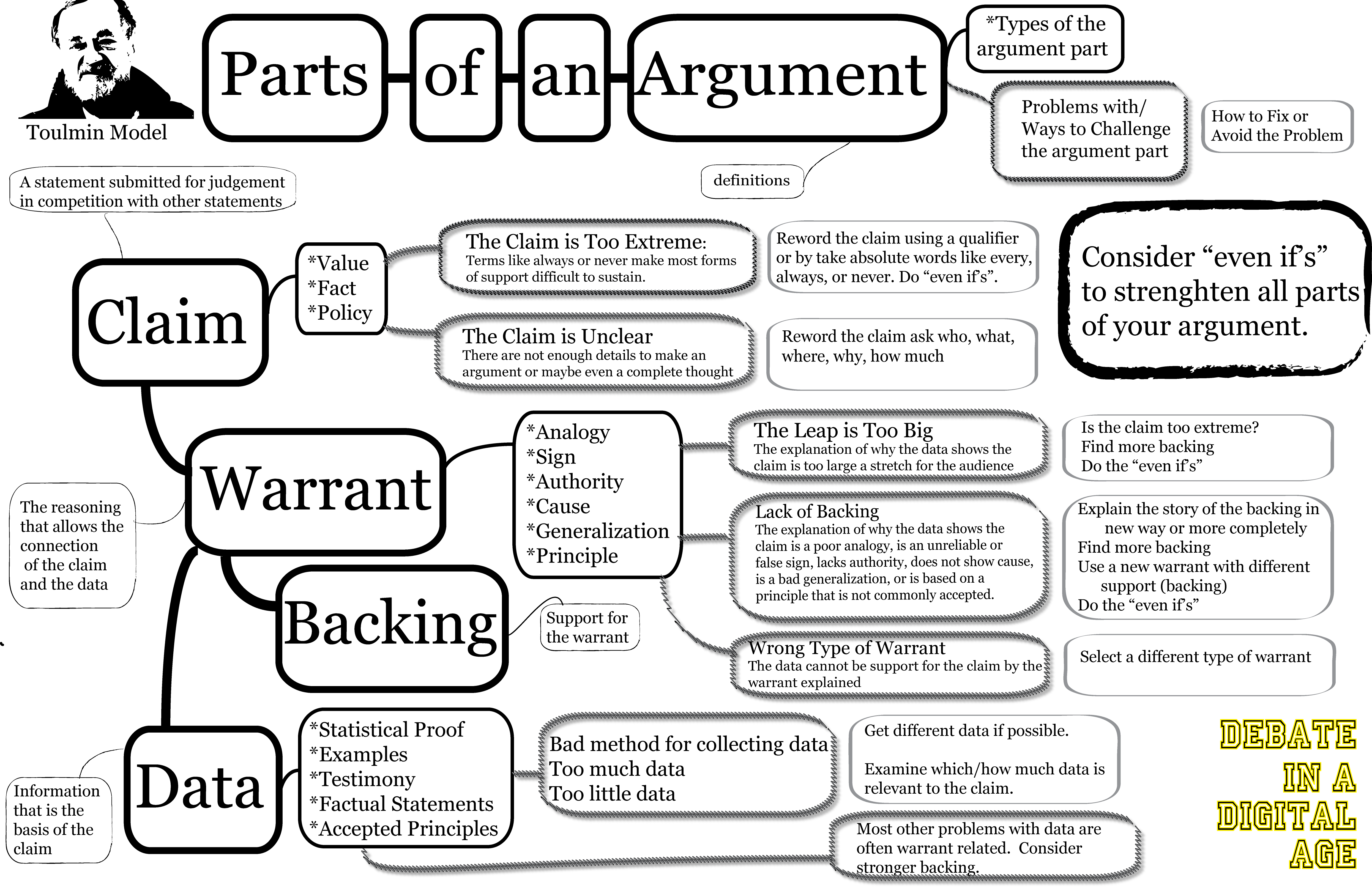

Argumentation theorists have developed alternative models that can appreciate the complexity and contingency of real speech and reason. Toulmin’s model supposes that an argument has the following parts: claim-warrant-backing-data-qualifier-rebuttal.[13] The key to this model are the warrants, the inferential leaps that connect claims and data, the data can be other claims. The power of this model is that it opens up a lot of space for nested argumentative functions, where one argument contains many others. Not necessarily the best for analysis of value claims, this model is useful for finding the sites where probabilistic claims about the future become stronger and weaker.

What is spoken:

Claim: Deflation is worse than Inflation

Data: Historical financial data for two-hundred years, indicates that depressions were more likely to be correlated with deflation, and that deflation linked events were longer and more severe.

What is unspoken:

Warrant: the use of correlation across examples provides a reasonable account of cause and effect

Backing: long term financial data are the appropriate information for this question, in the discussion of a causal claim a strong account of correlation can be developed as causation especially when definitive causation is impossible

Qualifier: the claim was structured around the idea of worse than

Rebuttal: the argument is designed to respond to the idea that inflation is the paramount fear for economists

This claim about deflation could then be situated as if it were a fact in a larger system of claims which we could call a case. The great strength of this approach for understanding practical discourse are the multiplicity of possible warrant and backing formulations. In the introduction to this book we established the idea of abductive reasoning, the prospect that a claim can be probabilistic and that we might decide between rival probable models of reality or facticity. For many interesting claims of policy, the collection of probabilistic claims is the most important dimension of the argument in the first place. It is not merely that deflation is worse than inflation, but that if the central objection to the development of good social policy is the risk of inflation, avoiding the risk of deflation would be a reasonable consideration. The next line of argument in the debate for this side should be clear at this point: we are closer to deflation than inflation.

For a full discussion of warrant structures, please take an argument theory class in the communication department.

Just as this model is strong for evaluating systems of probabilistic policy claims, it is unable to account for the multiplicity of value claims. Or if one did use such a model to account for values and aesthetics they might trend toward bizarre conclusions.

Luc Boltanksi and Laurent Thevneot offer a theory better suited for value based on Justifications.[14] Claims of value happen in different worlds of value. In this model, we are not judging policies but values and aesthetics, given their capacity to work with in established regimes of value. This is important as it gives us a way to deal with the empirical dimension of values discussion which is more than the stark utilitarian calculus that accompanies policy. It is in the alignment of the value and the test that a legitimate transfer of value is established. Illegitimate tests are those that attempt to use the wrong values and tests for a situation. It is conceivable that one might argue that something belongs in a different world, thus becoming subject to a different economy of value.

This model of value hinges on the agreement of people in a community to the development of a relevant test. For example, in the world of celebrity, the appropriate test is popularity. The actual means by which the tests function, often aesthetics, are not easily contested and are not of particular interest. You cannot declare: “fallacy, you felt wrong.” Legitimate orders are those that can be justified.

The standards by which we evaluate argument and the ways that ideas are moderated are always changing. When argument moves beyond a single simple claim of fact, argument itself is contested. The power of the code of argument is that we freely move between the levels of dialectical and rhetorical judgement: the ideas of logical validity and desirability continuously play into each other.

In practical terms, a justification must be provided, this must be a claim that declares a world (a setting), with a polity (a form or organization appropriate to that world), who then have a value (economy of worth), which can be judged with an appropriate test.

Example: who is the more important pop star today, Taylor Swift or Cardi B?

This is the world of fame. The polity are those who are a part of the larger manifold of the recording industry. Importance is judged by recent chart performance, the test being Billboard Hot 100 performance. In the last calendar year, Cardi B has out-performed Taylor Swift. Swift’s last album was a commercial disappointment, one of the fastest dropping ever. Furthermore, Bodak Yellow (Money Moves) by Cardi B displaced Swift at the top of the chart. We could thus reasonably say that Cardi B is the more important pop star on the basis of the rules of this community, the economy of worth, and appropriate test.

Value arguments are typically about the alignment and transfer of value. It is important to understand that the ability to access a reliable test decreases asmptopically as you approach the horizion of the individual and that this is a rhetorical rather than dialectical form. You are likely persuading the about the efficacy of the test as much as you are deploying it. At the lowest level, the test may be purely aesthetic.

3.2 Design

Design is a translational practice where insights from a number of distinct fields are applied to the making of something. The evaluation of the things made exists along a number of dimensions including the function and appearance of that thing. Donald Norman’s classic The Design of Everyday Things, applies a number of ideas from social research to make objects less bad, or even possibly good.[15] Celebrations of good design in this context tend of focus on stories of highly successful consumer products. Critical design researchers emphasize that this translational approach to design leaves too many assumptions to those that would commission a design, those in power.[16]

Any design needs a framework. At times this comes in the name “design thinking” which is typically associated with a particular firm.[17] It is not that design thinking is bad, but that there is no one special magical process for making a good design or even evaluating that design. The framework design thinking becomes a buzzword for the consideration of the aesthetics and function of a particular thing. The future oriented design proposed in this book focuses on the ways that we might think of design as enabling a broader conversation and collaboration, not as a mystical replacement for the university or skill development.

3.2.1 Affordance and Signifier

To avoid confusion, we should start by describing the use of signifier in design practice. For designers, signifier refers to a label, like instructions in an elevator. This is a more specific use of the term than one might find in semiotic theory. As Donald Norman describes in his work on complexity and design, often signifiers appear when a design has failed. The non-signified in this sense would refer to a design that would function with a minimum of symbolic or synthetic signifiers.

James Gibson coined the term affordance to refer to the properties of an environment to a creature.[18] Properties can include many things, like stairs. A door affords you entry, a car affords you transportation. Not all affordances are clearly visible. The idea of affordance is important because it offers a dialectical conception of the purpose of a design of a thing: it is about what becomes possible, not what is intentional or obvious. The provenance of this idea in the psychology of perception should not be forgotten. At stake in the affordance is the idea of the awareness of the user – this is a theory which enhances our awareness of the user by decentering their subjectivity. In other words, you can only truly understand how a person interacts with a system when you take the limits of that person seriously.

Given the preference for seemingly effortless communication, many designers would prefer that awareness of the affordance of a system be as liminal as possible. This is important because it tells you about the way of knowing that is present in design – the idea is that the designer can produce a world of almost effortless meaning. The code of the design invention melds into the thing as if it were an inevitable fact.

3.2.2 Simple, Complicated, and Complex

Following the definitions area derived from Donald Norman:[19]

Simple: in design simplicity refers to the occasion when a system fits with the psychological expectations of the user.

Complicated: the occasion when a system or thing does not fit with the psychological expectations of the user, or is emotionally fraught.

Complex: a thing has a lot of parts.

Simple and complicated have somewhat oppositional meanings. The optimal case for conventional design is when a complex thing is made simple. The biggest concern with simplicity is that designers, unchecked, have a penchant for inserting their own psychological position as that of the user. This is why a central tenant of usability theory (discussed later in this chapter) is “you are not the user” Design is a process of concealing and revealing, strategically, for a particular effect.

Once a student learns about brutalism, they see it everywhere. Many university buildings of the 1960s and 1970s are wonderful examples. Unfortunately, Oregon State is not lucky enough to have great examples. The repeated use of form that ostensibly reveals the structure of the building, the raw use of concrete. Brutalism is in a real sense the tangible result of high modernism. This was an approach to building that could transcend the everyday condition.

Nikil Saval concluded in the New York Times style magazine that the return of brutalism may be the harbinger of the end of the brutalist ethic:

But the renewed interest in the movement has yet to produce any meaningful change in the culture of what gets built and how. This resurgence has not — not yet anyway — led to any revival of interest in public-minded development. Politics has been divorced from architecture. In fact, love for Brutalism has often led to gentrification. Many social housing projects, such as Erno Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower in London, have become much sought-after private housing. Architecture bookstores sell postcard packs of the greatest hits of Brutalism; you can buy a Trellick Tower mug to sip expensive coffee in your pricey Trellick Tower flat. The aesthetic of Brutalism may at last triumph over its ethic.[20]

Brutalism offers what should be a simple solution to complex problems, yet the legacy of this approach to construction is terribly complicated.

A dualism of simple and complicated resonates with the design of our social networks and experiences in media research. Not all complicated things are bad – some things need to be complicated, others should not be simple. Design is best when use structured prompts to drive a chain of questions that can provoke a rich discussion. Even this starting point will fall away.

3.3 Aesthetics

Aesthetics are much maligned. The surfaces of things are positioned as being less than the things. The ways that we position discourses of beauty and value have profound effects on how the world is understood. Anti-aesthetic discourse is an aesthetic just as much the discussion of a particular appearance. This discourse supposes that one would have a preference for depths and timeless truths, rather than the things of the moment. Beauty is both a cause and an effect.

Aesthetics are a particularly useful point for understanding how desire functions in everyday life. The things that people prefer, the ways that they are valued and how those valuations interact in code are important and reveal much about how people are and want to life in the world. This is a powerful point with regard to both design and ethical theory as themselves depending on some conception of beauty. Aesthetic theory becomes something of a base level for reconstructing studies of design and persuasion.

This book does not contain a full theory of aesthetics, hopefully you will receive this in one of our courses that is dedicated to such concerns. The key point that you need to understand is that appearances matter and aesthetic concerns are not trivial. They are a key aspect of the development of codes and the moderation of desire. Your instructor is likely preparing examples for class that hinge on contemporary aesthetics.

Charlie Tyson, writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, notes that the aesthetic is making a comeback in academia.[21] The hinge for the aesthetic is quite similar to section two of this text: aesthetic experience when evaluated in an embodied sense is not mere decoration. Aesthetic judgement is real and important. Beauty is not the opposite of truth but something entirely different. It might be strange to think that an important function of college is to help you understand beauty, but it is an essential function.

3.3.1 Clothing

Walter Benjamin, one of the key figures in media studies, focused often on fashion. When people come up with new ideas and new approaches, a case of emergence, the conditions by which that novelty was produced collapse back into the same. This is why Benjamin was so concerned with the cyclical passage of vivacious creative energy into death. Clothing is a particularly useful site for classroom examples in this area, especially logos and novelty brands like Supreme.

In 2014, the New York Times fashion section reported that the hottest clothing trend was called “Normcore.”[22] It became apparent that the idea could just as easily be seen as something of a hoax: is it really a fashion trend to report that people are continuing to wear common items? It seems quite likely that people wearing “normal” clothing would be quite happy and comfortable. What is notable here is not so much the object of the sign, but the reflexive uptake of it. The idea of capturing a fresh new trend is a news story in itself. The idea of the trend, the code, and that fashion reporting without a concrete object rely on the idea that the code itself has become a social fact.

3.3.2 Cuisine

It should be apparent that all cuisine is a matter of culinary code. Food is a deeply contested site: strict rules govern the production of ideal food stuffs, ranked by complex mechanisms, scientific hygiene regimes aim to make the food safe, cultural codes with regards to what may be eaten are common.

We have already created the virtual in food. In the sense of advanced technique, we have the absolute peak of modernist cuisine, Myhrvold. In the everyday sense of the same thought Keji Lopez-Alt.[23] The approach to flavor here is to understand the chemical and process dimensions that make a particular food what it is. When embedded in an anthropological context this project is expressed by Alton Brown as Good Eats.[24] This is a model of the virtual and food that is personal, still very food like. Cookbooks are a fascinating code. Issac West argued that the cookbook is one of the most important sites where domestic everyday life interplays with ideology.[25] Some cookbooks are designed to help people learn in difficult situations, such as the Joy of Cooking, the books described this paragraph reinterpret cooking through the world view of techno-science.[26] Instead of a massive compendium of all that one might do with ingredients or a full tabulation of recipes, these scientific cookbooks select particular food products and then isolate the exact semiotic resonances of the sensory experience of the food. Recipes are then redesigned around the maximization of gustatory pleasure based on those codes. Idealized aesthetic visions of the food stuff reimagined around the chemistry and biology of the food itself.

Chemical labs in New Jersey and Minneapolis have already given us virtual cuisine.[27] Foods stabilized and flavored continually. Stabilized seasonality. Consistent flavors. No spoilage. Technologies like McDonalds represent the precision stabilization of that which would be tasty.[28] It becomes possible to think of culinary codes in terms of the production of sensations that were never possible before.

Food is the place where we can see what an enfolding really is – a blending of technology that has remade the earth, makes life possible, and is deeply enjoyable, yet wracked with danger. This short section on food is included as many semiotics texts rely on extended discussions of different foods, such as McDonald’s French Fries. Why the fries? McDonald’s technique for the management of potato moisture was a major advancement, the transcultural mythos of McDonald’s in terms of organizations and branding, and the seeming excellence of the product itself, as testified to by the legendary food writer James Beard.[29] Of course you can’t have these fries, the underlying technology that produced them relied on beef tallow and was retired in 1990.

Cuisine here is a chance to consider the simulacrum: what happens when flavor is more real than reality?

3.4 Recording Devices

For the most part, many media systems require some means of recording perceptible reality. It is possible that a system could produce a synthetic video or something else without a recording in the first instance. Yet, these systems still maintain a recording that can be reproduced as if a recording had existed in the first instance. In section begins with technologies for recording and then moves into the discussion of transport and reproduction. Paper has been common for many years, although the paper of the past may differ from what you are expecting – the ‘rags’ of nineteenth-century journalism were literally fabric newspapers. The means of recording have a critical imprint on the text.

3.4.1 Image Recording

Recording devices allow the transmission of information through time, which is the inverse of the momentary transmission of information through space. Among the earliest methods for transmission we have are cave paintings and architectural forms like pyramids. Many of our recording technologies quickly degrade.

Film is an emulsion on a thin, transparent, flexible strip. When light is projected through that strip, an image is recreated. The chemistry of such a strip is an important consideration in the development of a recording system. Early film strips were extremely unstable and flammable. Chemicals used in a system like this would need to be extremely photosensitive and reactive. Some older films have literally decayed into vinegar. The design of these emulsions is important.

Lorna Roth described the problem of film color standardization: getting film developers to produce emulsions that could adequately render all people, with the wide variety of human skin tones was difficult.[30] Even the basic idea of color standardization depended on checking against Shirley Cards, which privilege certain ways of looking at film. Even today, computer filters are unable to fully map the faces of people who do not look a particular way. Image recording technologies, as they are designed to record particular people in a specific way, rely on assumptions about how people look or should look. This is not to say that those assumptions will not change.

Television broadcasts were recorded using film systems, as video tape did not exist. Even the underlying tape technology was not fully developed until after World War 2 when the cellulose tape technology of Europe was introduced in other places.

Images today are recorded as computer files for storage on flash memory. There are two chips, discussed at some length in section two: CCD (charge coupled devices) and CMOS (charged metal oxide semiconductor).

Likely changes in the future of the camera include longer battery lives and more sensitive chips, these would work better in lower light. Things less likely to change are the lenses that organize the light that is focused on the sensor.

Non-lens technology has been developed at CalTech using optical phased array sensors. Cameras in this sense are two-dimensional planes.[31] These sensors are currently limited, but they could present new possibilities.

The biggest change in image recording in the last decade was not the reduction in price of CMOS, but the ubiquity of cellular phones. Each of these devices includes a camera that people can use at any time. Mirrorless cameras with larger sensors will also become ubiquitous.[32] These cameras may lack the sophistication of professional equipment, but for many purposes they are more than enough.

3.4.2 Sound Recording

The basic technology of sound recording is the microphone, which is a fundamentally similar technology to the speaker. Before the digital, the signal passed through a sound system was fundamentally similar, the recorded electrical signal would pass through the wire which then reproduced the sound with no reprocessing. If you played with a crystal radio set as youth, you know that analog radio is magic in as it broadcasts enough energy to receive the signal and a usable signal as well.

The traditional types of microphones include those that produce an electrical signal including:[33]

Condenser: a diaphragm produces a signal in a capacitor

Moving-Coil (dynamic): an external magnetic source producing a signal in a coil that is allowed to vibrate

Ribbon: a ribbon of material instead of a coil

Crystal: certain crystals transduce a signal in response to a vibration

Optical microphones measure vibration using a fiber optic lead or a laser. Changes in the reflection drive the detection of the signal. The key to reproducing a sound is the production of a document with the frequencies of the sounds present at the time of recording. It makes sense then that if someone could simulate those waveforms, thus allowing entirely synthetic sounds to be created with far greater control and precision than those that came before.

Sound is then either recorded as an analog signal or processed using a quantizing chip and stored as a digital audio file.

3.4.4 Recording Experience

This is a horizon for future technology. Our current modes for storing experience are for the most part literary. Walter Benjamin seemed to find that Proust offered something of an attempt to store the experience of a thing through rich description.[34] There is an important idea best expressed through psychoanalysis that can help us understand why experience is so hard to process – when more signifiers are added to a system or code, they retroactively shift the meaning of those that came before. A full representation of a place or space will likely require extensive mapping both of the physical environment but also of the person experiencing it.

3.4.3 Codecs

All information that is recorded is stored in some format. On a film strip, the image was retained as a discrete cell that would move as the strip crossed the light source. In terms of the images processed by digital sensors, the raw volume of data can be striking. Early digital field production cameras used heavy cards (like the P2) that would allow high resolution footage to be captured and stored on an array of flash chips. Those early cards could store gigabytes of data, which in raw meant about ten minutes of footage. At this level, streaming video would be bandwidth prohibitive. For transmission over the internet, the information must be encoded differently. The H.264 codec allowed much lower bit rates, the VO9 codec came later, and more recently the AV1 codec has allowed Netflix to further reduce the total volume of data flowing through the internet.[35]

The drawback to encoding the video differently is the loss of data. Courts may not accept transcoded video, it is too easily faked. When data is transcoded, a great deal of what is lost is the internal structure, color data that may not appear to the viewer but is lost. If one then tries to do substantial editing to the file after it has been transcoded from, for example, Apple Pro Res 422 to H.264, the corrections will not look as good as if they were made on the original file.

Codecs are the medium of the future. New media experiences exist between ultrahigh capacity sensors and display systems.

3.5 Editing systems

The editing of information is one of the essential properties of the production of new media. Editing before the advent of digital technology was often destructive, a film strip would be cut and taped back together to make a coherent strip. With the advent of the digital nonlinear editor the capacity for the production of new media was dramatically increased. There are a few types of digital editors that we need to consider:

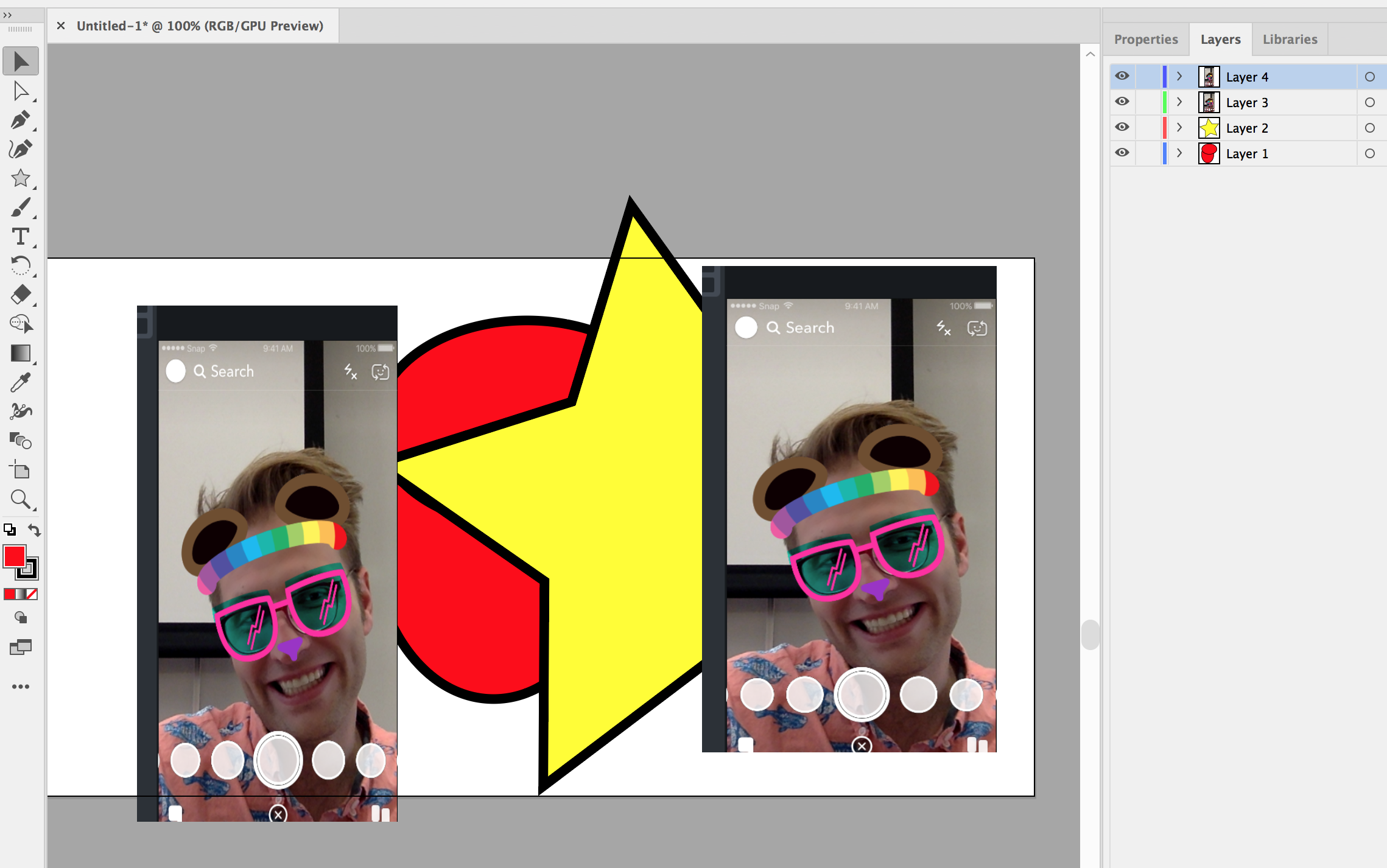

3.5.1 Image Editing (Orthogonal Layer Interfaces)

If you are editing a single image you have likely used an orthogonal editing interface, this allows you to create a series of layers that may modify an image or mask parts of that image from modification. Some familiar editors in this space include Adobe Photoshop. The layers dimension is present in many different products, providing a high level of control and simplicity for image development. The most recent developments in this field are those that can produce new content in ways that sample the underlying image, such as a content aware fill. Although this interface metaphor is unlikely to change, the new element here is the likelihood that these elements will appear in other systems.

This model presumes the painters algorithm where the view of an image is composited along a z-axis from the top down. The distinction between raster and vector based editing systems is falling away.

The key to this system is that we must have some way to render a static image element.

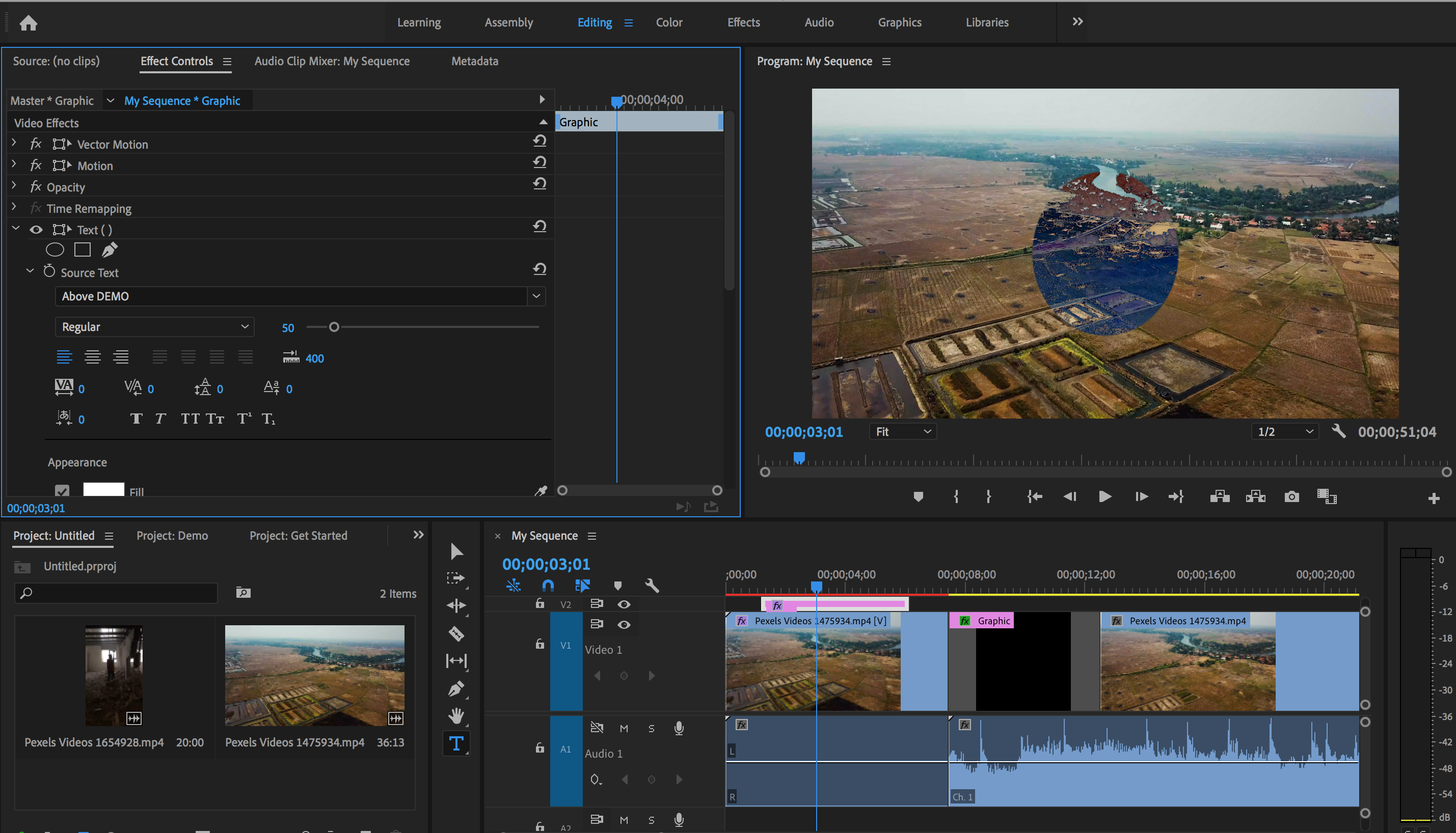

3.5.2 Digital Non-Linear Editors

The fourth dimension of video and audio is time. Music, after all, is the organization of tones in time. When we organize video or sound clips the combinations can produce rich results that vastly exceed the sum of the parts. The timeline provides a well-structured way of apprehending the project itself and controlling the dynamic state of the product as the viewer encounters it. Before 2002, this technology was unproven, it did not take long for DNLE to prove that Hollywood films could also use these techniques to produce powerful libraries of clips and rapid plastic changes.

As of 2017, only thirty-one major motion pictures were shot on traditional film.[36] Conventional workflows use a DNLE system to produce a list of edits to be made to the film proper. Typically, this is produced in the form of an Edit Decision List (EDL) which is presented as a form of metadata.[37] For sound manipulation, the technology relies on the same organizational theory. Music is produced by organizing tones in time.

Once situated in a stream of time, cinema becomes possible. The dimension of the perception of time is the key to the understanding of cinematic experience. The cinematic itself is unstable, the presumption to this point has been that the frame order of the time axis would drive the experience. Interactive systems challenge this in profound ways.

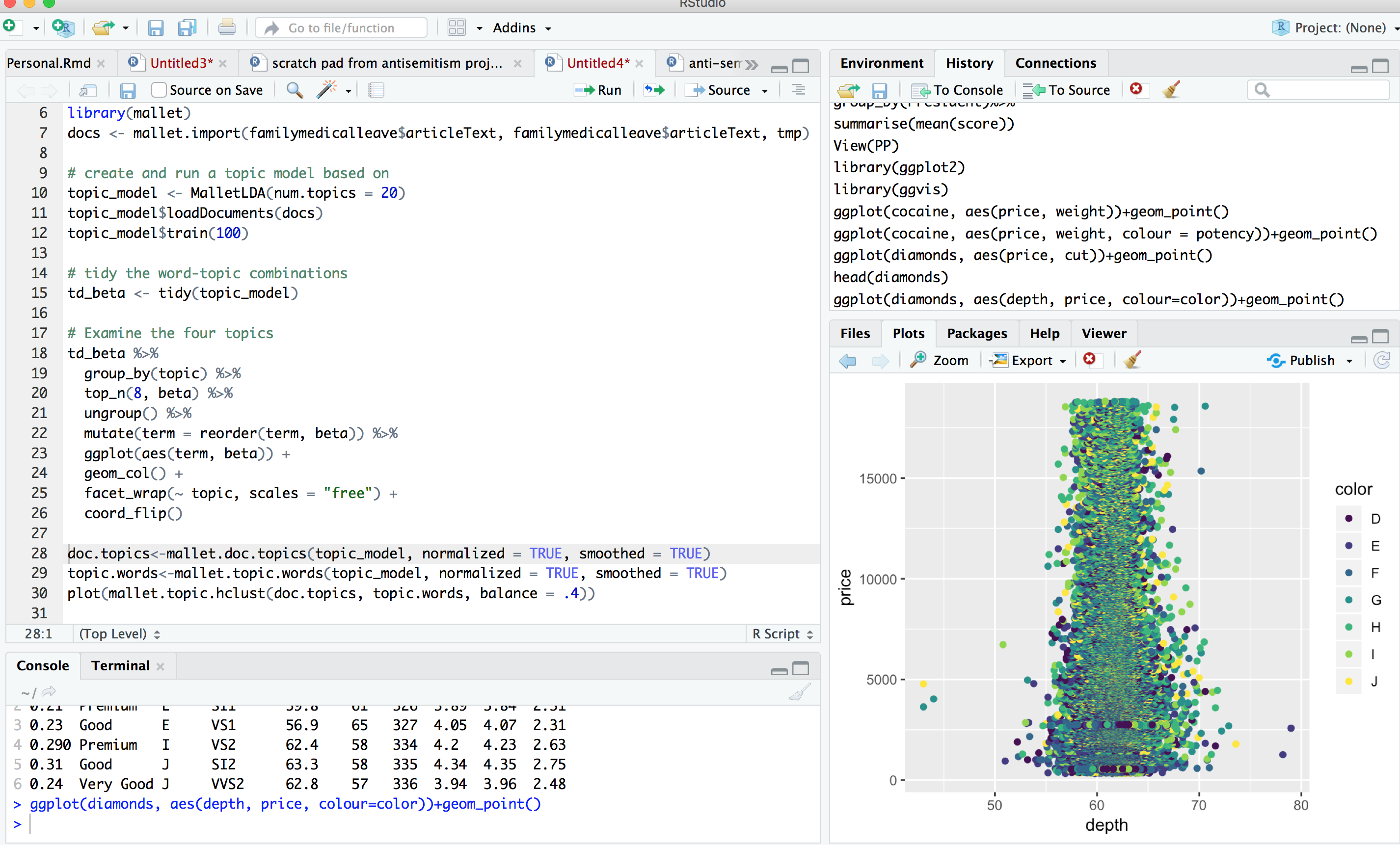

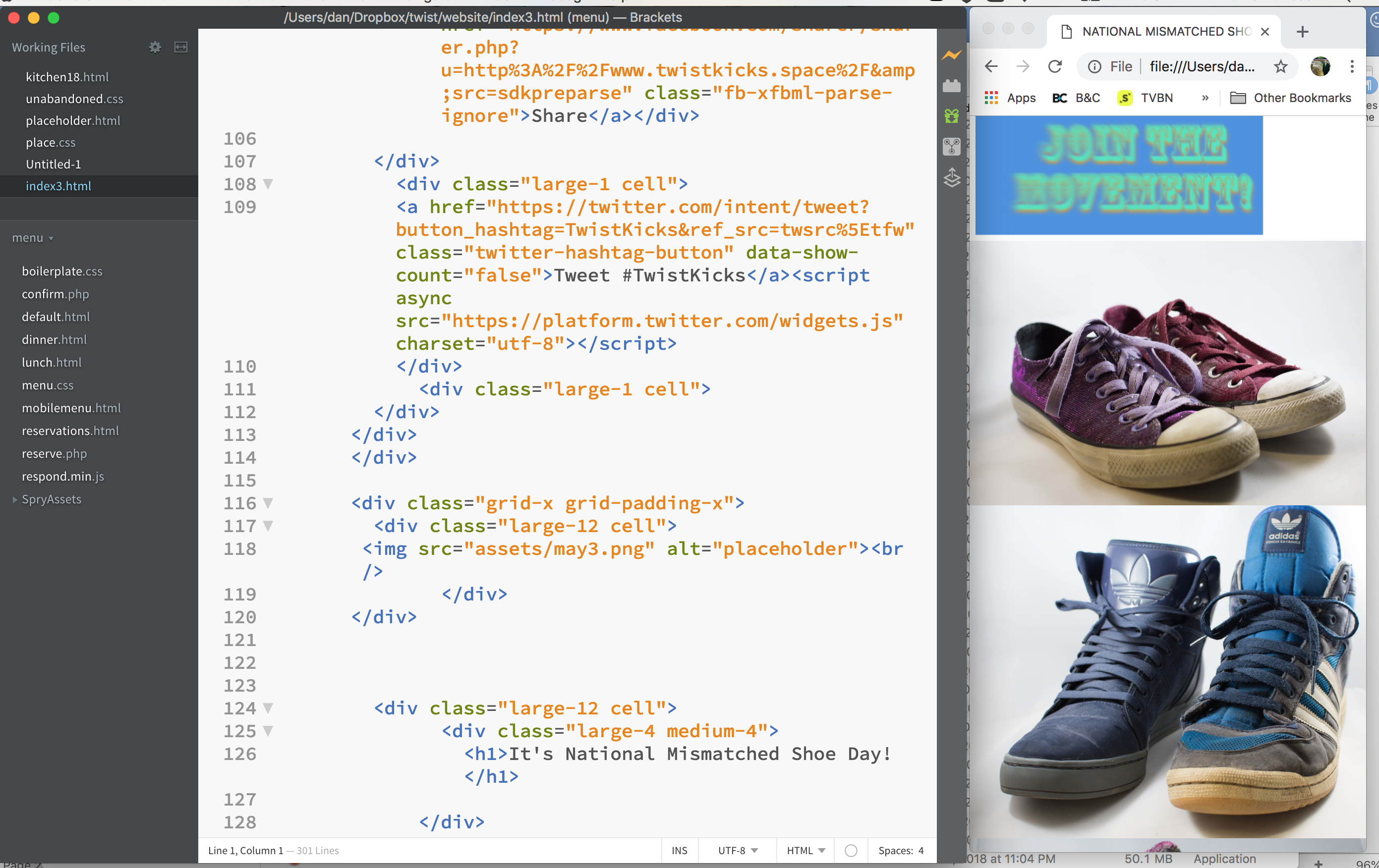

3.5.3 Integrated Development Environment

The interactive element of media depends on the design of systems which have the capacity to respond to user intervention into the state of that system. Keyboards allow users to provide sophisticated text strings to the system. Pointing devices all users to experience the graphical user interface. These systems then are being manipulated by users and produce a variety of different states depending on the input. These editing systems can range from basic text editing programs (where code can be written) through sophisticated development platforms like xCode.[38]

What these systems are providing is the capacity for users to use a variety of provided abstract representations to write economical code that could produce the intended results. The complex structures produced with these systems could include autopoetic systems which organize and produce content for the users as an ongoing flow.

Each of these approaches to editing will continue, it is likely that interfaces for each will continue to have an appropriate use.

3.6 Output devices

In this section, we will consider the devices that allow us to access the information encoded.

3.6.1 Optical

3.6.1.1 Resolution

Optical media are presented for the most part on screens. Early screens relied on tubes with scanning beams or projectors that would modulate light from a powerful source. Technologies that operate on this property include movie screens and tube televisions. The refresh rate of the device depends on the principal of persistence of vision. For a film system, the refresh rate was typically 24 frames per second, for a television system the refresh rate of the system was linked to the AC frequency of the power grid. In the United States, this means approaching 60 hertz, in Europe 50. When the beam would scan, it would go every other line. The total resolution, or pixel density, was a function of the persistence of the two fields of scan in time. On those old televisions, there were 525 lines, 480 of which were visible.

For an analog television, the interlaced scan with the number of lines would be expressed as 525i. Students today are accustomed to resolutions of at least 720p. P in this case stands for progressive scan, every line is illuminated on every scan, which typically now is not a scan but a refresh of pixels which happens at far higher rates than 29.97 fps.

Contemporary systems use high densities of individual pixels. When the pixel density exceeded 300 pixels per inch Apple branded this the “retina” display. At extreme resolution, the eye is not capable of seeing the individual dots, much like how the eye could not see the individual dots of the offset printer. The pixels are OLED (organic light emitting diodes) which are a form of transistor integrated technology that produces light. These diodes are capable of producing very high contrast images with deep black colors. For larger devices, the future technology is the QLED, also known as quantum dots. Each crystal of this system can produce a pure color, which then can be blended through the additive scheme to produce an image.

As of this draft, 4k displays are increasingly common. It is highly likely that resolutions will continue to increase. The more interesting question: do these higher resolutions have a great impact on semantic and aesthetic dimensions of experience?

3.6.1.2 Stereo-optical

In the mid 2000s there was a surge of interest in stereo-optical films. These were the next big thing, and films were being reprocessed for display on a stereo optical system. The hype was short lived – many users do not enjoy stereo-optical films and the quality of such experiences was poor. Stylistically stereo films seem to insist upon simplistic jump scares and crude objects reaching out of the screen. On a very technical level, the stereo film misses were discussed in our vision section – most visual cues are in fact mono-optical. Depth can be interesting, but it needs to be aligned with the other codes of the filmic experience. Thus, a well-produced and designed Avatar could be a spectacular stereo epic, while a buddy comedy run through an algorithm would not be.

There are two primary stereo-optical cues: stereopsis and convergence. Stereopsis refers to each eye receiving a slightly different signal. Convergence is the slight crossing of the eyes to focus on an object at short or intermediate range. The addition of these factors in a scene can produce the perception of depth.

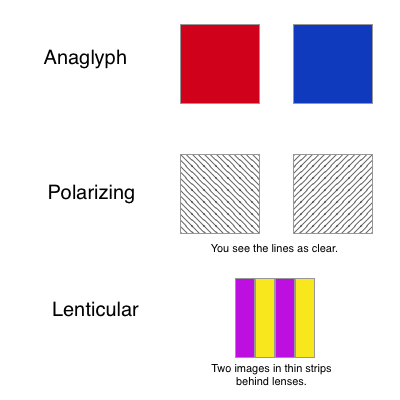

There are three major technologies for this display:

Lenticular overlays: lens layers attached to a flat image, the lens produces a level of stereopsis.

Anaglyph: a filter is positioned in front of each eye corresponding to a colored filter on one of two projection cameras. Typically, this is done with red/blue or magenta/green pairs which tend to correspond with the color response of the retina (discussed in section 2).

Polarizing: the same basic design as anaglyph but with an angled polarizing filter and lens combination for the glasses and projectors.

Exercises

Demonstration 1: EYE DOMINANCE

With both eyes open, point at a spot somewhere in the room, like a clock. Now close each eye, you will notice that one of your eyes likely steered your hand despite both eyes being open while you were pointing. This is your dominant eye – you now have proof that the integration of your visual field is not perfect.

Demonstration 2: POLARIZING FILTER

Polarizing sunglasses are common, find a friend with a pair (anything from Warby Parker will work). Find an older cell phone, an iPhone 5S will work beautifully, newer phones will work as well. Place the sunglass lens between you and the phone. Rotate the glasses. You will see the phone screen darken or even disappear. When the filter and the photon source are aligned, they come through, when they are not aligned, they light is blocked.

Holograms: Instead of recording the image itself, a hologram records the interference pattern produced when two beams of highly focused light intersect.[39] The film becomes an interference recorder. When hit with another laser the film produces a reproduction of the interference from the original scanning laser. The advantage to this method of scanning is that many possible points and angles are recorded on the film.

Holography is not a new technology. The necessary elements for holograms are decades old, and unlike many forms of contemporary stereo optical photography, are technically difficult. If you use a contemporary flagship phone, interesting images cued by the movement of the phone relative to a static image source are quite impressive.

3.6.1.3 Rendering

Bob Ross’ painting programs are enjoyable. When you watch him, you will notice that he has a very precise method for rendering objects. He starts with those furthest and layers over them. His assumptions about light and color follow a clear painter’s algorithm, where that which is closest to the foreground is rendered last and in the most detail, distances are rendered with a broader brush and less detail. This is much the same way that most computer graphics are rendered.

The alternative is called ray-tracing. In this method, objects are supposed to exist in the world and light (shadows and reflections) are not determined deductively but inductively. Cars was the original film to use this method for rendering and it offers superior results for complex scenes. Now, the methods in rendering are working through the objects once again.[40] With increasing power in graphics rendering the capacity for real time ray tracing of games is in the very near future. If this will increase the degree to which games are meaningful or impactful is another question.

Photorealism is the end goal of all current rendering technology, which makes sense given that the end perception point is the human eye. Realism on the other hand is a far more flexible concept. There is in some sense an assumption that the future of graphics technology hinges on the production of ever more photorealistic images, at the same time some particularly powerful experiences like That Dragon, Cancer have demonstrated that a lower level of detail in some parts of the envelope can be offset by enhancements in others. This game, which you may be assigned to play for class, removes critical macro details like faces, while emphasizing the small details like the textures of surfaces and real sounds.

3.6.2 Sonic

Speakers use magnets to convert an electrical signal into physical motion. Sound is a vibration. For the most part these sounds are produced by vibrating a cone, other technologies may use incisor diffusion to vibrate larger surfaces.

The key is that the underlying physical properties of the system do not change. Smaller objects cannot resonate at the low frequencies of a great bass performance. An ear bud will not rock your body. Yes, woofers do real work.

Innovation in this space will likely come with the use of larger fields of speakers, more precise tuning, and careful, meaningful sound design. Sound is a case where the resolution of the underlying technology (what a speaker is) allows further refinement of the experience of that thing (sometimes paradigm shifting innovation is less robust than simple improvement). Systems in the future may detect the locations of pared devices and the space around those devices to optimize how many speakers and in which bands those speakers operate.

The most profound dimension of sonic development is not in the entertainment space, but in the creation of adaptive devices. Mara Mills history of the miniaturization of the hearing aid is powerful: it was both the original use case for the integrated circuit and a form of technical miniaturization that transformed everyday life for many people.[41] It is the social role and image of technology, rather than the elements of the system which drive reality. At the same time the demand for invisibility of the device and continued stigma is a powerful factor:

Today, the imperative of invisibility largely persists as a design standard for hearing aids, with the demand for miniaturization often limiting device functionality. Recent examples of fashionable earpieces compete with new models of ‘‘completely-in-canal’’ invisible aids. As a long view of hearing aids makes plain, hearing loss has been stigmatized despite the increasing commonness of the diagnosis, and despite the fact that moderate hearing loss can be remedied bytechnical means. Just as inexplicable is the obduracy of the stigma that adheres to the technology itself—when hearing aids have otherwise represented the leading edge of personal electronics, and when they exist as one configuration of the same components found in so many other appliances.[42]

This is a powerful example as the benefits and expansion of communication enabled by the device, yet the coding of culture continues to dramatically shape how sensation is produced. Speaker technology is relatively stagnant, when we expand to consider what hearing and listening technologies could be the realm of possibilities and representations dramatically expands.

3.6.3 Haptics

The primarily strategies by which sensations are produced come in the form of small electric motors and electric charges. When these are mapped to other stimuli a full faceted haptic experience may be produced. At the same time, the dimensions of perception tied to the position of the body and perception of relative space may not be fully simulated by the system. More importantly, the actual kinematics of a human body are not effectively reproduced by an electric motor bar, point, or puck. Consider your perception of a brush against the skin of your forearm: there is both the friction of skin on skin, but also warmth, pressure, and variation across the stroke. There are at least five dimensions to plot. It would make sense that scandalous applications of the technology have been dominant so far – these are the low hanging fruit for the production of sensation with a simplistic criterion for success.

An important question raised by David Parisi, the major theorist of haptic communication: Are touch-screens haptic? His answer: to a degree.[43]What is important to understand about touchscreen systems is that they are not fully haptic – they are not the entire enfolding of sensation, but a very limited slice of that envelope. Force reactions on a Nintendo DS or a cell phone screen are intended but for one patch of skin and one set of interactions. The rhetoric of the touch screen is instructive here: the image always features a finger touching the screen, it does not move through the screen to form a contact point with the world beyond.[44]

What is especially striking from an interface studies perspective is the degree to which the ostensibly haptic interface of the touchscreen displaces what would have been richer interaction points like sliders.[45] Haptics demand the consideration of the relationship between the limited slice and the entire sensory enfolding.

3.6.4 Aroma and Flavor

Devices for the production of virtual smells and tastes were discussed in section two. For the most part the strategy here is to simply load a handful of relevant chemicals into a system that can then produce those chemicals on command. What is so difficult about these senses, is that they lack the deep similarity of basic inputs that the first three output systems share. There is no EM spectrum of spicy. There are technologies for taste which can use electrodes in the mouth to produce an electrical signal that tastes like something. An 800hz signal in the mouth tastes like lemon.[46]

It is possible that our best technologies in this area are in fact barred from use. Increasingly consumers are interested in natural foods, the taste of strawberry must come from the shattered cell walls of a morsel, not from a bottle. This is an interesting case where the purely refined sign is not really what people want, as if the sign of cherry is not so much the almond like taste but something else entirely.

Smell and Taste will not change, but the ways that we feel about particular aromas and flavors will. The new media of the future in these spaces does not look like the simulation of an entire enfolding, but the production of new experiences and technologies that would be consumed in the world as we know it: this is another important point to remind you that the virtual does not depend on goggles, you already inhabit that virtual world.

3.7 Abstraction

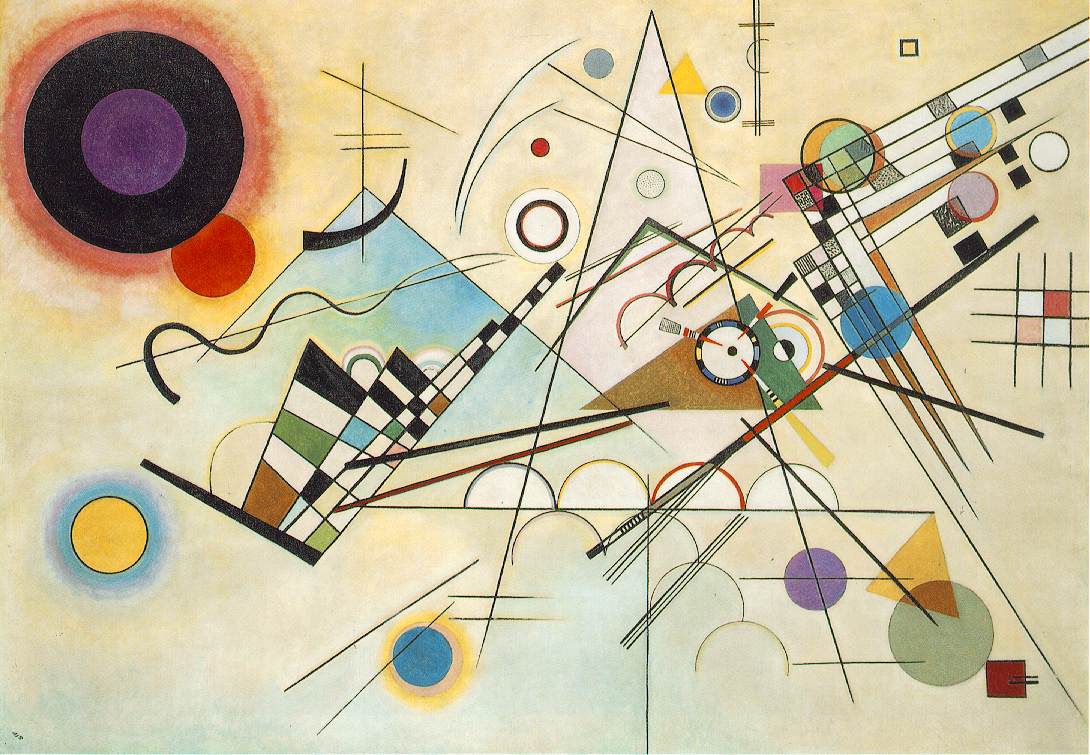

Abstraction is a powerful concept. In art, the move toward abstraction allows the artist to be free of the purely iconic or mimetic, to develop works that have qualities that might evoke a feeling without relying on so many established identities. Piet Mondrain and the artists associated with the de stijl movement attempted to reduce the work of art to the most basic elements, in the final form blocks of color set into grids.[47]

In software, abstraction allows the development of many powerful tools. Instead of taking a nearly pointillist orientation toward the encoding of software to actually run on the chip itself. At the lowest level, machine code drives the utilization of the gates that make the computer work. At higher levels, programing languages allow users to deploy abstractions. As the programming moves to higher and higher levels, the abstractions become increasingly understood by users. A page written in HTML and CSS may actually be quite readable by a human. Over time, language developers may produce new abstractions for functions that were once accomplished with much more labor at a lower level.

The grid aesthetic is almost second nature for the web today. Users are not expecting a sophisticated layout that requires them to relearn how to use a computer. These tabular layouts were extremely common and clever websites could be made long before standards for our current layouts existed. Over time, users began to use more devices (such as phones and tablets) and the need for layouts that could adapt became clear. Web developers were then writing div descriptions that would operate in a variety of contingencies. Today, the HTML 5 standard includes abstract representations of positions on the page and adaptations. For APIs and software libraries, many of the functions they offer for data analysis of manipulation are not new. In computer science, this is called refactoring. When code is rewritten with base instructions as functions for repetition and ease of reading, that code is improved.

Abstraction as a semiotic process allows the formation of powerful symbolic signs that greatly increase the power of communication. Yet every abstraction conceals and excludes. An important dimension of our study and production of the future is the role of the abstract in granting access to systems for new developers and designers.

3.7.2 Graphical User Interface

Among the most powerful abstractions for new media is the graphical user interface. Instead of asking that users compose lines of code to access their information of perform operations, the GUI produces a continuous visual state where a pointing device can allow users to move blocks of information or select items in a metaphorical world of positions and objects. Users intentions are then mapped onto visual properties which become the interface with the complex system.

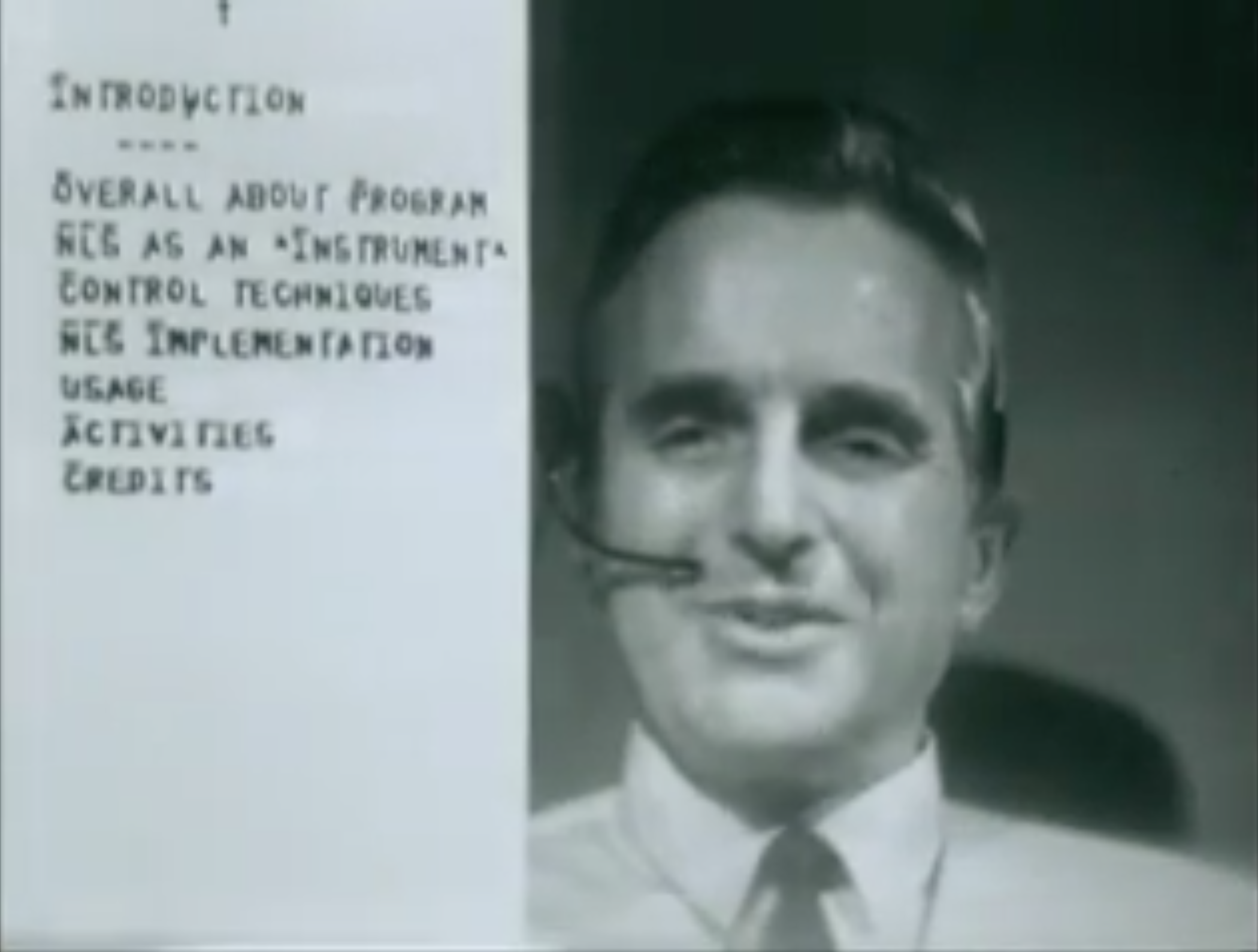

In 2005, Jeremy Reimer wrote a strong history of the GUI (to that point) for Ars Techinca. It is linked here and is suggested reading for everyone. A key detail in this history is the discussion of the Mother of All Demos – the occasion on December 9, 1968 where Douglas Engelbart demonstrated the first computing system with a graphical user interface (a mouse moving abstract blocks on a screen). You may notice that aside from a few changes, the basic technology from his round screen, the basic theory of the GUI is unchanged.

Graphical user interfaces hinge on the use of a pointing device. Typically, this has meant a mouse, trackball, touch-screen, or touch-pad. These devices allow the user to direct the system to recognize the importance of a functional point in virtual space. More recently, the role of the dedicated pointing device has been supplemented by touching directly on the screen. As multi-touch interfaces become increasingly common, users will begin interacting through touch in increasingly sophisticated ways.

Keyboards are relatively static. There are a number of ergonomic alternatives to the current layout. If the hands are positioned slightly differently repetitive stress injuries may be mitigated. Some new designs suppose that a projection of a keyboard, paired with sensors for where the fingers move over that light will replace the physical interface.

A great deal of change can be expected in this area, with-in some boundaries. It seems that the underlying trajectory toward less typing will continue. Typing has a high level of information entropy, people misspell things all the time. Further, it is reasonable to expect pointing devices to become more sophisticated but to so sophisticated that they will become cognitively taxing. Beyond the cognitive, a new set of limits may come into play: the structures of the human wrist. This also goes for keyboards. Is it really cognitively worth it for people who keyboard to learn a non-QWERTY format? For this author, the answer is decidedly no. The future of the keyboard does not hinge on creativity, as much as it does on cognitive and physical limits. Any new innovation in the keyboard space will need to replace the functions of the existing keyboard for many users in a way that provides some very real benefit. Change in pointing devices is more likely than a change in keyboards.

In the market, currently there are roughly three major philosophies for GUI design. Apple’s human interaction guidelines push for a more photorealistic system of icons and animations. Google’s Material Design tends to push of a geometric look that uses a variety of layers to indicate priority and control. Microsoft’s Fluent Design emphasizes the underlying usability of a particular thing.

It is highly likely that all three of these frameworks will change. You will also notice that this list does not include the standards proposed by Facebook, Snapchat, or any number of other firms. Approaches to the graphical user interface will be various and important for understanding interaction on the whole.

3.7.3 Human Computer Interaction

The study of human computer interaction has become a robust field onto itself.

Usability studies, developed by Jakob Nielsen, contends that the primary focus for understanding interaction should be the user task.[48] The designer of a system has some particular thing that the user needs to be aware of and able to manipulate. Usability research deploys a number of different social science strategies for the analysis of user tasks, especially those that can work across the life cycle of the project. The drawback to this approach is that it is involved in problem-solving, not necessarily problem finding. Tasks are provided by the client, the goal is to make the thing work so that the task can be completed.

The challenge of these approaches to affect and HCI (human-computer interaction) is the question of ends. Consider these four major paradigms for the study of human-computer interaction in the introduction to a major research volume: Emotional Design, Hedonomics, Kansei, and Affective Computing.[49] Emotional design is best described in this book as it is tied to usability studies. The aesthetics and configuration of a system are matched to the design of a system through a number of approaches to the evaluation of both the users and the system. Hedonomics supposes that a system must be designed to maximize the pleasure of the user, while Kansei engineering is an example of a framework that supposes a strong ontological typology of users. Consider for a moment the continuing popularity of personality types: what if we designed systems to match with the results of the Meyers-Briggs inventory? Finally, affective computing is a cybernetic model which would describe a situation where the computer might try to continuously adapt to, and modulate the affect of the user. The differences between these approaches are useful for our theory. Each one of these approaches must theorize who the user is, how many different types of users there are, if they can be designed for in advance, and if a universal design is possible.

Human-computer interaction is not a single concept that one simply learns as a set of best-practice recommendations, but an entire domain that fuses an ongoing trajectory of research and development. Every time Facebook, Snapchat or any of the other big social network companies change their interface you see this in action. They have particular ends that they must satisfy – keeping you engaged with great content while inducing clicks on advertisements. The balancing act between those goals is not solved directly by an equation. Furthermore, the aesthetic progression produced by these interfaces changes the conditions by which they are designed.

3.7.4 Brain Interfaces and Other Inputs

All media technologies are providing a poor substitute for telepathic communication. The goal for interface technology is the development of interfaces that would allow thoughts to be scanned directly from the brain and then delivered directly into the brain of another. This seems to be a long way off. The deepest problem here would seem to be neuro-plasticity: the brain of each person is decidedly different. Consciousness, as much as it is understood, is not a mechanical property of the brain that can be located in a single point but an emergent force of a number of different processes all blending together.[50] In 2008, Gary Small’s research was commonly discussed as providing evidence that Google searches prompted the brain to utilize more oxygen than reading – of course the problem, as he maintained, was that the interpretation of more oxygen utilization meant nothing.[51]

N. Katherine Hayles argues this in the context of the development of literacy: there is no single part of the brain that produces the ability to read, and we know that the development of reading and writing appeared as a paradigm shift in human behavior.[52] The key seems to be that multiple parts of the brain were developing reading like parameters at the same time, when these were linked the possibilities were dramatic.

Consider the model necessary for full telepathy: thoughts must be extracted and transcoded into a meaningful for reproduction through a decoding process at the receiver. Anything less than that, and we are once again dealing with a semiotic process where signs are presented to the senses. Thus, our concerns throughout this course with simulation and standardization. Singularity is unlikely.

This does not mean that interfaces involving the brain are not promising. Scanning methods have allowed scanners to read text from the brain. It is possible that new systems will allow those who are locked in to rejoin the world of symbolic production. This is wonderful. Cognitive pupillometry is a well-established concept, as the pupil dilation changes we can detect shifts in the level of cognitive work.[53] Eye focus scanning allows military helicopter gunners to track targets. Galvanic skin response and body position detection can offer rich interface possibilities. Motion scanners offer great fun for headset games, artistic work, and software interface.

In a world where people elect to carry computers (cell phones) there is much data to be collected about the physical location of phones, their relative speed, the accelerometer information (how is the phone moving in space), among other sensor inputs. People elect to use these devices to store biometric data as well, meaning that all of these ambient inputs also provide a world of information for interface with virtual worlds. What the challenge is with these other interfaces is that they are not so neatly intention driven.

There will be much change in the world of alternative interfaces. It is important to keep in mind that the change here is likely limited by the capacity for input into the human as well as the interposition of semiotic code relationships. This returns to the metaphor of the enfolding of the virtual: it is not simply finding a way to get thoughts into or out of a person, but that the ways that those thoughts refer to each other and others held by other people is an equal dimension of the experience of that which is virtual.

3.8 Games

Game theory has offered an important set of conceptual tools for the analysis of complex iterative systems. What does that mean? Games are important because they have multiple turns, and within those turns, the players consider the actions that others may take, in the context of multiple constraints, mechanisms, and story elements, crafting provisional strategies to reach victory or defeat.

Katherine Ibster provides two key points that distinguish games from non-game media: choice and flow.[54] The two points are interlinked – it is not merely the game continues to move but that the choices you make along the stream effect the flow. Flow exists in a tenuous equilibrium between challenge and player skill, great emotional design allows the user to stay in this seemingly ideal zone where they are learning and experiencing change.[55] It can be useful to consider the types of uncertainty generators that are present in games, as proposed by Costykian, including the player, a random generator, and other players.[56] Games vary greatly based on where they find the randomness necessary for fun.

Beyond the solitary game, playing together is important: it is the depth of interaction between people that makes these game systems truly deep.[57] Game theory relies on this assumption to provide critical insight into human behavior akin to the results of a system of equations: the assumption in a game involves active people attempting to arrive at some outcome.[58] Games are everywhere and are deadly serious.

Ian Bogost’s conception of procedural rhetoric is particularly useful for understanding the future of media, the ways that particular software affordances can be mapped to the experiences of the game player.[59] Rhetorically the video game must be understood both through its total semantic content and the coded means of delivery. The peak of games for Bogost is a complex system where a user is made to disidentify with their own position by manipulating a complex system: Sim City.[60] This perspective is ludological.

Kishonna Gray makes the counter point: rather than evacuating games of identity the identities in the game must be challenged.[61] This is narratological: the game is a story that is a way of understanding the world, it is not a psychological procedure but a way that people experience stories that make their personal worlds. Games are stories that deeply compelling. To see them as less than that or as flat objects that people are not invested in misses their power.

This framing device, a debate between positions, has some truth in it but also is largely artificial. I present it this way so that we might understand the two lines as they braid into the future: there will be new stories, but also new ways of interfacing with the system that will produce many new affordances. There is some value in debunking such a distinction between play structure and story, but also great utility in reading each.

At the same time, games are critical for understanding human behavior. As both a literal structure and a metaphor, games describe a recursive pattern of behavior. Thus, as a form for thinking about the future, games are important as they give us some sense of the real dynamics by which strategies form.

3.9 Narrative

Stories are everywhere. Stories increase emphatic awareness of others situations. Stories may even be the basic structure of being itself. Stories aren’t going anywhere – but the content of those stories will change. It is also important to understand that ideas from prior stories are referenced in future stories. This is called intertextuality. The play between the present consideration of a text and all of the meanings loaded into forms and tropes are important.

Joseph Campbell identified a commonly used structure known as the hero’s journey: this formalist template can be identified in many successful stories.[62] This does not mean that those stories are all the same or that there is no variation, but that rhetorical forms evolve over time. Changing stories have a low velocity. The mythic structure is particularly enduring regardless of the choice to include vampires or Mr. Darcy.

Leslie Baxter and Barbara Montgomery provided a different approach to understanding narrative in everyday communication – flowing from Bakthin, they see our personal stories as a product of forces that push people together and pull them apart.[63] This is an important idea as it can give us a way to read stories that are developing and those that are less than logically coherent. Reading the future is not a matter of binary logic, but of complex fuzzy interaction across space and time.

Kenneth Burke approached the use of narrative in public life through the idea of the pentad. The core of the pentad are the five basic units of a drama: scene, act, agent, purpose, agency.

| Scene | The Setting |

| Act | The Action |

| Agent | The Character |

| Purpose | The Reason Why |

| Agency | The Method of Action |

The pentad provides us the foundation of a theory called dramatism, where a formal structure can be applied to any number of communication phenomena. Professor Ragan Fox at CSU-Long Beach has a spectacular full chart that anyone interested in learning Rhetoric must review.[64] These appear as “ratios,” where two elements of a story combine to form the core logic of that story.

Where Campbell’s approach leads us to consider the sort of stock stories that populate our worlds, Baxter and Montgomery provide resources for seeing how those stories are translated into action in our everyday lives. Burke, on the other hand, provides a near guide to how the ratios might be deployed in everyday life. This returns to the point of the semiotic interposition of signs and facts.

3.10 Immersion

Marie Ryan argued in an essay over a quarter of a century ago that the real immersive power of the game is in the intertextual enfolding of the user.[65] Team chat and interaction are what is really interactive, merely pushing buttons is not. This is an important idea. What does it mean to have enough contact with an interface to say that you are in communication with a conscious system? The common answer to this question is the idea of the Touring test – the idea that a system that could simulate relatively banal interaction over a textual transmission would be AI. In this time period, we can see a remarkable number of systems which are capable of producing far more vivacious simulations of human interaction.

It is likely that what constitutes immersion will change. As social media systems have reached maturity, it has become clear that they are a vector for hateful and hurtful communication. The friendly banter that would have made a world compelling has fallen away.

Interactivity is merely the chain of indexical reactions to user input. Ryan proposed a useful framework for evaluating interactive controls: speed, range, and mapping. These controls allow us to have some vocabulary for evaluating different levels of interactivity with a system.

The most interesting question: do people actually want immersion? Are any of our new technologies that much more immersive than an excellent television show or a novel?

3.11 Language

It is likely that language, particularly the semantic dimensions of everyday code will change most. This is totally tubular. As much as ideas are constantly in flux in an attempt to symbolize what we mean, which is always to a very real degree barred from what other people might mean, language will be dynamically shifting in an attempt to keep up. This is not just a property of idioms, grammatical structures and spellings shift often as well. There are so many languages and codes. It should be clear why humanistic research is so important, we need to understand how these code systems work and how they are changing.

- Claude Shannon, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” The Bell System Technical Journal 21 (October 1948): 379–423, 623–56. ↵

- John R. Stuart, Language As Articulate Contact: Toward a Post-Semiotic Philosophy of Communication (State University of New York Press, 1995). ↵

- Kathryn E Anthony, Timothy L Sellnow, and Alyssa G Millner, “Message Convergence as a Message-Centered Approach to Analyzing and Improving Risk Communication,” Journal of Applied Communication Research 41, no. 4 (October 2013): 346–64. ↵

- This is a strong resource developed for a course at the University of Chicago in 2007. Hua-Ling Linda Chang, “Semiotics,” Keywords Glossary::semiotics, 2007, http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/semiotics.htm. ↵

- John E. Joseph, “Ferdinand de Saussure,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, June 28, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.385. ↵

- Sean Hall, This Means This, This Means That: A User’s Guide to Semiotics (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2012). ↵

- Daniel Chandler, “Semiotics for Beginners: Signs,” 2006, https://www.cs.princeton.edu/~chazelle/courses/BIB/semio2.htm. ↵

- Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Jonathan Cape (Paris: Noonday Press, 1991). ↵

- McGee, Michael Calvin, “The ‘Ideograph’ a Link between Rhetoric and Ideology,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 66, no. 1 (1980): 1–16. ↵

- Nancy Frasier, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy,” Social Text 25/26 (1990): 56–80. ↵

- Michael, Warner, “Publics and Counter-Publics,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 88 (2002): 413–25. ↵

- Greene, Ron, “Rhetorical Pedagogy as Postal System: Circulating Subjects Through Michael Warner’s ‘Publics and Counterpublics,’” Quarterly Journal of Speech 88 (2002): 433–43. ↵

- Thomas A. Hollihan and Kevin T. Baaske, Arguments and Arguing: The Products and Process of Human Decision Making, Third Edition (Waveland Press, 2015). ↵

- Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot, On Justification: Economies of Worth, trans. Catherine Porter (Princeton University Press, 2006). ↵

- Donald A. Norman, Living with Complexity (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2010); Donald A. Norman, The Psychology of Everyday Things (Basic Books, 1988). ↵

- Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds (Duke University Press, 2018). ↵

- Lee Vinsel, “Design Thinking Is a Boondoggle,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, May 21, 2018, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Design-Thinking-Is-a/243472. ↵

- Chapter eight is the classic on affordance theory. Your instructor should likely provide you a copy of this chapter for additional discussion. James Jerome Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Psychology Press, 1986). ↵

- Norman, Living with Complexity. ↵

- Nikil Saval, “Brutalism Is Back,” New York Times Style Magazine, October 6, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/06/t-magazine/design/brutalist-architecture-revival.html. ↵

- Charlie Tyson, “Why Professors Distrust Beauty,” Chronicle of Higher Education, June 3, 2018, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Why-Professors-Distrust-Beauty/243548. ↵

- Alex Williams, “Normcore: Fashion Movement or Massive In-Joke?,” New York Times, April 2, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/03/fashion/normcore-fashion-movement-or-massive-in-joke.html. ↵

- J. Kenji López-Alt, The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science, n.d., accessed October 26, 2018. ↵

- Good Eats was an important culinary television program that may be in production when you read this. ↵