Unit 6 – Introduction to International Fisheries Management

Introduction to International Fisheries Management

Contents

Introduction

Governance and Sustainability of World Fisheries

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

Conflict Management in the Convention

Introduction

The primary, holistic purpose of international law is to establish and set forth a set of internationally agreed-upon norms—the instruments are elaborated upon in international discussions with policy objectives reflected in agreements (treaties and conventions). International law is uniquely based on the tension, common interests and common goals among sovereign nations who are the parties to each agreement.

All international instruments, and those governing fishing perhaps most of all, evolved and transformed out of the ancient principle of freedom of the seas (mare liberum, see Unit One) put forth by Hugo Grotius and maintained by nations for centuries. The transition from the perspective of ocean resources as limitless—a free-for-all commons—to the current (and still developing) set of governance structures for a hungrier and more crowded planet, represents a remarkable change.

While nations make their own laws with which to govern themselves, international law emerges out of ambitious, vigorous global discussions and the need to determine goals and principles, equitable and sustainable guidelines for resource distribution and security of nations. Practices that were previously customary become codified in international conventions; codified conventions therefore reflect international custom. Finally, note that in international law nations are “states.” To avoid confusion, States (meaning countries) will be capitalized.

The purpose of this unit is to provide fisheries and wildlife and other natural resource and environmental management professionals and students with walking-around knowledge about how fisheries are managed at the international scale.

Governance and Sustainability of World Fisheries

The United States possesses legal and market-based tools to combat unsustainable and illegal fisheries from outside domestic waters. The 1971 Pelly Amendment to the Fishermen’s Protective Act, 22 USC 1971-79, and the Lacey Act of 1900 that makes it illegal to import and sell fish and shellfish illegally caught (16 USC 3372(a)(2)(A). Amendments to the Magnuson Stevens Act (2000, and 2002) added provisions to indirectly regulate the illegal shark fin trade (Shark Finning Prohibition Act of 2000, 16 USC 1857(1)(P); see also The Shark Conservation Act of 2010, 16 USC 1857(1)(P)). Under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), 182 nations and the European Union (EU) protect approximately 35,000 species of plants and animals.

Certification schemes for sustainable fisheries offer another market-based approach. According to FAO’s Nicolas L. Gutierrez (2016), 30 percent of global stocks are overexploited, despite recoveries in some fisheries and some regions. Certification has early success. Seafood certification labeling can raise awareness and issue visibility, and create higher product values as an economic incentive. Gutierrez notes that well established programs such as the nonprofit Marine Stewardship Council (MSC, https://www.msc.org) have reached ten percent of global fisheries.

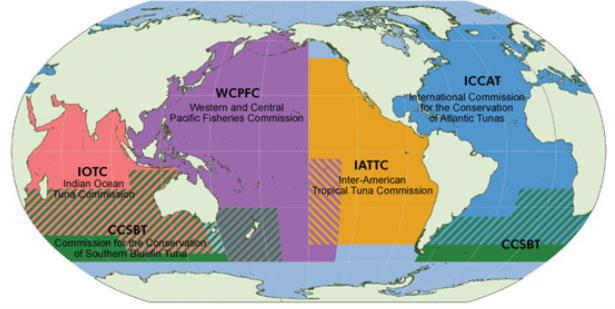

International fisheries are regulated by 17 Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs), consortia of countries (coastal States, and distant water fishing nations or DWFN) collaborating based on financial and conservation interests, mainly in commercially valuable species but sometimes on ecosystem or habitat also. Not every ocean region is governed by any form of RFMO. RFMOs are diverse, focused on a single or multiple species. For example, five RFMOs manage tuna. Governed by treaties and other international agreements, some regions and nations participate in more than one organization. Each entity’s structure for decision-making is different, although all have a science committee that provides recommendations. Decisions result in plans for annual implementation plans that are consensus-based through voting. While RFMO decisions are binding, compliance varies; according to PEW Charitable Trusts (2012), these organizations could be strengthened by having stronger incentives, political weight, sustainable management mandates and authority for enforcement.

The World Bank (WB) and FAO studied and summarized the status and value of fisheries sustainability in the landmark report, Sunken Billions: The Economic Justification for Fisheries Reform, first published in 2009, and updated in 2017 (see Unit 6 Resources in appendix).

Within an era since the early 1990s that included stagnant and declining fisheries, the 2009 WB/FAO study pointed to a global fisheries crisis based on observations that despite falling catch, the era featured an “increase in the level of fishing by a factor of four.” Even in the face of a doubling of global fleet size and three-times the number of those involved in fishing, catches did not increase.

Uncertainties complicating sustainability include ongoing ocean changes attributable to climate (rising temperatures, changing currents, acidification, rising sea levels). The purpose of the WB/FAO study and 2017 update is to estimate, as accurately as possible, the costs and benefits of achieving sustainable global fisheries, to encourage fishing nations to understand and address the economic loss of $83 billion (2012) that declining fisheries represent (the loss to which the sunken billions report title refers).

The report states that if effort were reduced, the oceans living resources would have a chance to regenerate, leading to four improvements (fish biomass by a factor of 2.7, 13 percent increase in annual harvest, 24 percent increase in unit prices in part because of recovery of high-value species severely depleted, and annual net benefits increase from $3 billion to $86 billion).

Sunken Billions hypothesized two ways to generate recovery. Although unpopular and therefore impracticable, the first option listed in the report nonetheless provides useful comparison: fishing effort reduced to zero followed by maintaining effort at some level deemed optimal. The report estimates this method would recover over “600 million tons in five years and then taper off…” The report’s second hypothetical method is to reduce global fishing effort by five percent per year for a decade. The report estimates the second method would bring fisheries to the same level (600 million tons) in around 30 years.

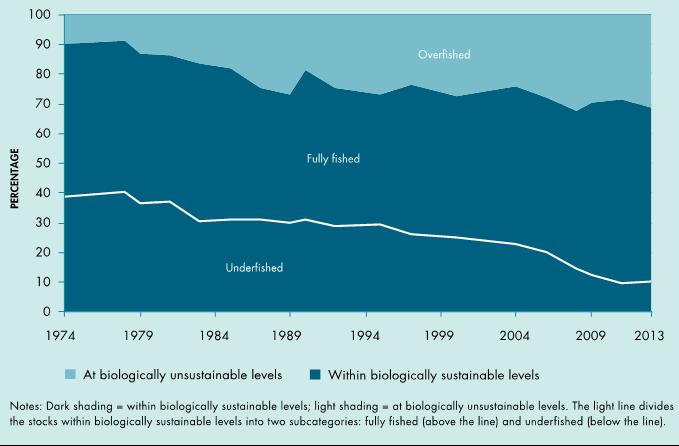

An FAO report (State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016) finds 31.4 percent of commercial fish stocks worldwide are presently fished at a level that is not sustainable, three times the 1974 level. Offset by aquaculture, worldwide fish consumption rose above 20 kilograms per year for the first time. The role of aquaculture is considerable: FAO reports that, in 2014, 35 countries (3.3 billion people, or 45 percent of world population) “produced more farmed than wild-caught fish.

The RFMOs, as they gain scientific and compliance capacity, are uniquely positioned to lead fisheries recovery and sustainability. They are the backbone network of international fisheries management.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

For convenience, the provisions of the Convention most pertinent to this unit are provided in the appendix of resources for Unit 6. They are:

Part V, EEZ Articles 61 – 68

Part VII The High Seas

- Conservation and Management Articles 116-120

- Environmental Protection including Pollution Articles 207-212

Enforcement Articles 213-22

UNCLOS is aptly known as the ocean’s constitution because it provides a holistic vision of cooperative ocean governance spanning the exploitation and management of living and nonliving resources, navigation, marine environmental protection, the resolution of disputes, and scientific research.

Over coming years, areas likely to be revised or expanded might include modernizing the Convention’s fisheries provisions, and the sections on deep seabed (“the Area” designated as part of the heritage of all humankind) issues, especially pertaining to mining of manganese and other valuable metals.

In reviewing the Convention’s sections on fisheries, you may notice the (now familiar) maximum sustained yield (MSY) metric. The Convention’s emphasis on MSY is becoming controversial among some international fisheries experts. The Convention is increasingly faced with complex realities of overfishing, itself a product of multiple forces (weak governance and enforcement, high product market values, fleet overcapacity, or ever-advancing capture technologies). Moreover, the oceans are undergoing profound change (increasing acidity, water temperature, melting ice). Management paradigms in wealthier nations, such as robust science-based management, and ecosystem-based management (EBM) could help inform more prudent decision-making. However, the funding, technology and capacity that could support contemporary tools to improve the concept of MSY toward decreasing overfishing can be lacking in developing nations.

The Convention’s myopic emphasis on the fish themselves (total allowable catch, size, quotas) completely overlooks enormous pressures represented by larger environmental and economic forces. Some experts would like to see MSY modernized and more nuanced to take into account important contemporary influences on global catch including data on global and regional fleet count, boat size, gear types, and fisheries subsidies, as well as area-based bans and moratoria (Hey, 2012).

Conflict Management in the Convention

UNCLOS provides four separate systems for dispute resolution; these feature forums that are third-party, formal, and compulsory. Article 287(1) states that parties in dispute may choose from the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS, under Annex VI), a special arbitration form (Annex VII, the default forum) and a fourth tribunal (Annex VIII) that oversees fisheries, scientific, environmental, and navigation questions.

The following sites provide insights into current controversies.

International Court of Justice (ICJ, The Hague, Netherlands)

The International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS, Hamburg, Germany)

Unit 6 Resources (appendix) contains excerpts from UNCLOS that are relevant to international fisheries management and many other useful global fisheries references.

Unit 7 will present aspects of current problems in ocean management.

Notes: Hey E (2012), The Persistence of a Concept: Maximum Sustainable Yield, 27 The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 763-771.

Unit 6 Study Questions

- Should nations that are meeting management and sustainability goals share technology and expertise with nations that are falling short? If so, what existing forums or processes do you recommend serving as vehicles for progress?

- What is at stake nationally and internationally in the case of declining and overfished species?

- While there are still important stocks being rebuilt, the United States and North America as a region, are among the most well regulated fisheries internationally, with notably smaller fleets. Based on what you know from the readings in Unit 4 and elsewhere, what key principles and tools might underlie these successes?