Unit 2 – Management of Protected Marine Species

Management of Protected Marine Species

Contents

Introduction

The Endangered Species Act of 19 (ESA)

The Marine Mammal Protection Act of 19 (MMPA)

Introduction

In 2018, 2300 species are listed as threatened or endangered (1625 domestic, and 675 foreign) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries (also called the National Marine Fisheries Service, NMFS).

Two federal agencies share the administration of the ESA and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). The Secretary of the Interior, through the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), administers the list of threatened and endangered species under ESA and also oversees CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). The USFWS manages land and freshwater species as well as eight marine mammal species. The Secretary of Commerce, through (NOAA/NMFS) is in charge of determining listing or delisting for marine species and anadromous fish (species that go back and forth between fresh and salt waters during their life cycles; examples are steelhead and salmon). NMFS currently has jurisdiction over 161 threatened or endangered marine species (including 65 foreign species).

With regard to both the ESA and the MMPA, there is federal preemption. The term means that, under the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution states are subject to and must obey federal law; in order to prevent conflict with state agencies or conflicting laws, the requirements of ESA and the MMPA are paramount, their policies rule management or enforcement questions pertaining to endangered and marine mammal species. Importantly, however, the ESA (in §6(f)) encourages state law to be more protective; the ESA also contains provisions for cooperation with state partners. Also, in cases where the MMPA is more restrictive than the ESA, the MMPA’s protections take precedence.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973, 16 USC § 1531 et seq.

In the Endangered Species Act opening statutory section,

(a) Findings The Congress finds and declares that—

(1) various species of fish, wildlife, and plants in the United States have been rendered extinct as a consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern with conservation;

(2) other species of fish, wildlife, and plants have been so depleted in numbers that they are in danger of or threatened with extinction;

(3) these species of fish, wildlife, and plants are of esthetic, ecological, educational, historical, recreational, and scientific value to the Nation and its people; … (https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1531)

Two agencies administer the ESA: the US Fish and Wildlife Service under the Secretary of Interior (USFWS, species of birds, land animals, and freshwater animals, polar bears, walrus, manatee, sea otter, and sea turtles when on land) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under the Secretary of Commerce (NOAA, anadramous and marine species including fisheries, marine turtles when they are in the ocean).

Under the Act, “threatened” means a species is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future. “Endangered” means the species is at risk of extinction throughout all of its range, or a significant portion of its range (SPR), which the Act does not define. To fill the gap, in 2014 NMFS and USFWS issued a policy guidance, after public notice and comment, to provide more precise meaning to SPR.

“Range,” under the guidance refers to the geographical area where the species is found at the time of listing. SPR, which only comes into play in certain situations, means that there is an area that contributes so substantially to the species’ overall viability that

“without the individuals in it, the species as a whole would be in danger of extinction (meriting an endangered status), or likely to become so in the foreseeable future (meriting a threatened status) (NOAA Fisheries).

In other words, if a species is threatened or endangered wherever it occurs, it will be listed as such (no need for the SPR guidance). The purpose of the new policy, while the agencies expect it to be applied infrequently, is to afford species ESA protection before “large-scale declines or threats occur throughout the species’ entire range.” (June 27, 2014 NOAA/USFWS Policy Guidance on SPR). The SPR guidance has important implications for Distinct Population Segments (DPS).

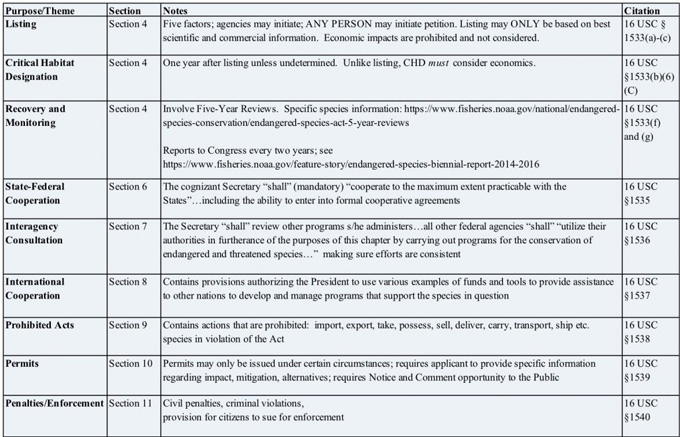

Key provisions of the ESA include Sections 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Pertinent ESA Sections, adapted from NOAA Fisheries, which contains a concise description of the procedural process for listing.

Under ESA Section 4, listing decisions must be based solely on any one of five factors and the best scientific and commercial information available.

- The species’ habitat or range is at risk of present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment.

- The species is over-utilized for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes.

- The species is threatened or endangered due to disease or predation.

- Existing regulatory mechanisms are inadequate.

- The species’ continued existence is affected by other natural or human-caused factors.

ESA Section 4 covers the process and deadlines for the listing of threatened and endangered species (16 USC §1533; refer to the procedural flow graphic in the appendix of Resources for Unit 2).Section 4 of the ESA requires the identification of habitat when the species is listed (unless such habitat is undetermined, in which case critical habitat must be identified within one year) critical to the species’ recovery, thus helping focus conservation activities and funding. There are rare exceptions. If the cognizant Secretary concludes that factors, including national security or economic cost of critical habitat designation are greater than the benefit to the species in question, areas may be excluded or simply not designated. The exception applies if even identifying critical habitat could worsen a threat to the species (16 USC § 1533(b)(2); https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1533) Recovery plans, described in 16 USC 1533(f), must incorporate three factors: site-specific management actions to achieve the species’ conservation and survival, objective and measurable criteria that, once met, would allow the species to be delisted, and time and cost estimates to implement the necessary measures.In conjunction with Section 7’s consultation between agencies, critical habitat designation also helps ensure, overall, that federal agencies are required to broadly consider the effects of their actions, avoiding actions that “are likely to destroy or adversely modify critical habitat.” Examples of such activities Section 4 seeks to prevent include “water management, flood control, regulation of resource extraction and other industries” ensuring that federally permitted activities do not inadvertently conflict with habitat goals (February 11, 2016 Rule).ESA Section 7(a)(2) contains consultation provisions. Consultation, begun as early as possible in the initial phases of a federally permitted activity (for example, construction of a dam) is intended to allow the involved agencies and non-federal project proponent more thorough consideration of resource conservation needs. This proactive approach can decrease the necessity for major project modifications later in the process. If a listed species is present, and that species or a designated critical habitat, will not likely be adversely affected by the activity then the consultation concludes. The consultation statutory time limit is 90 days; regulations provide for an extra 45 days for USFWS to prepare a biological opinion.The biological opinion contains an analysis of whether the activity will likely have an adverse effect on the listed species or critical habitat. If adverse effects are likely, the opinion must further include any alternatives that are reasonable and prudent sufficient to allow the project to advance.If the proposed project could result in an “incidental take” of the listed species but not to the extent of jeopardizing the species’ existence, the USFWS must include a statement noting that in the opinion effectively authorizing an incidental take. However, according to USFWS, the agency may include an incidental take statement in either a jeopardy or non-jeopardy opinion. In short, the legally imposed but collaborative process of Section 7 ESA consultation prevents foreseeable adverse impacts by promoting project design modifications to avoid negative effects. (For more information, see https://www.fws.gov/endangered/esa-library/pdf/consultations.pdf)

Along with Section 4, Section 10 of the ESA is perhaps the most controversial of the statute’s provisions and governs how the federal government reviews and issues permits for activities that could in a “taking” of a threatened or endangered species.The law defines a taking (in Section 3, Definitions, at 16 USC § 1532 (19)):The term ‘take’ means to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.

The regulations define harm (50 CFR 17.3) as ‘an act which actually kills or injures wildlife. Such an act may include significant habitat modification or degradation where it actually kills or injures wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding, or sheltering.’In the course of ordinary activities, avoiding harm to wildlife can be challenging. On land, Section 10 is frequently seen in development situations where listed species are present. Section 10 is available to landowners, states, Tribes, counties, and companies to obtain permits for “incidental” takes, that is, takes that could occur in the ordinary course of otherwise legal activities. With regard to Section 10 permits in conjunction with development, landowners must have an approved habitat conservation plan (HCP) that includes the evaluation of likely impacts on the listed species, steps to avoid the impact (or to minimize or mitigate the impact) and a statement of funding set aside to ensure the steps are followed.In the ocean, as on land, instances requiring Section 10 permits to take a listed species require the consideration of alternatives that would result in lower impacts. In 2016, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decided a case dealing with the ESA and similar provisions within the Marine Mammal Protection Act in the context of cetaceans and US Navy sonar during training missions. The case (Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. vs. Pritzker, 828 F.3d 1125, Ninth Cir. July 15, 2016) eloquently presents the difficulty of the analyses of harm and balancing that the ESA requires, and the exacting process that the ESA and MMPA require agencies to conduct. The Pritzker case will be discussed at the end of the unit.The Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 (16 USC Ch. 31)The MMPA focuses on identification of species of concern and the promotion of ecosystem protection, research, and international cooperation.

In the Marine Mammal Protection Act opening statutory section, Sec. 2 The Congress finds and declares that—(1) certain species and population stocks of marine mammals are, or may be, in danger of extinction or depletion as a result of man’s activities;

(2) such species and population stocks should not be permitted to diminish beyond the point at which they cease to be a significant functioning element in the ecosystem of which they are a part, and …they should not be permitted to diminish below their optimum sustainable population. Further measures should be immediately taken to replenish any species or population stock which has already diminished below that population. In particular, efforts should be made to protect essential habitats, including the rookeries, mating grounds, and areas of similar significance for each species of marine mammal from the adverse effect of man’s actions….(https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1361)

Marine mammal management is consolidated under federal agency management. The MMPA works in concert with the ESA. The prohibition on “taking” in the MMPA transfers the burden of proof from agency managers on the conservation side of the equation to the party requesting a permit for incidental take, who must demonstrate that the activity it plans to undertake will not cause harm to the species. Important definitions include the following. MMPA (16 usc § 1362(13)) defines take as:“to harass, hunt, capture, or kill, or attempt to harass, hunt, capture, or kill any marine mammal.” The associated enforcement regulations add detail to the statutory definition (see 50 CFR § 18.3). Interestingly, the Act prohibits feeding marine mammals in the wild an addition that NMFS added in 1991 to curb this practice among tour boat companies. The original Act and regulations did not define harass, which in 1994 clarified that harassment includes section (18)(A):…any act of pursuit, torment, or annoyance which—

(i) any act that injures or has the significant potential to injure a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild; or

(ii) any act that disturbs or is likely to disturb a marine mammal stock in the wild by causing disruption of behavior patterns, including, but not limited to, migration, breathing, nursing, breeding, feeding, or sheltering.

16 USC § 1362(18)(A).Military training has special relevance to marine mammal protection. The MMPA dedicates special harassment language with regard to this important activity in section (18)(B).In the case of military readiness activity….or a scientific research activity conducted by or on behalf of the Federal Government…the term ‘harassment’ means—

(i) any act that injures or has the significant potential to injure a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild; or

(ii) any act that disturbs or is likely to disturb a marine mammal stock in the wild by causing disruption of behavior patterns, including, but not limited to, migration, breathing, nursing, breeding, feeding, or sheltering to a point where such behavioral patterns are abandoned or significantly altered. [emphasis added]

Incidental (unintended) take occurring during commercial fishing is covered by special permits from the Marine Mammal Authorization Program. Nonfishing activities also require permits. Examples include US military training, offshore energy development (including alternative energies), construction projects, and scientific research. Special permits are provided for Alaskan natives (who participate in co-management) for taking for purposes of traditional subsistence, clothing, and so forth. Just as with the nation’s fisheries, NOAA Fisheries conducts stock assessments for marine mammals, provides additional management details (https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/topic/laws-policies#marine-mammal-protection-act). The US military is not required to obtain permits for taking during actual combat or times of war. Preparing for real-life engagements at sea requires training expeditions; for the US Navy, submarine use of sonar is part of that training. Since marine mammals communicate across vast distances, military sonar has the potential to interfere with communication as well as to cause harm to these animals’ hearing (specifically at levels at, or higher than 180 decibels (dB) referred to as Level A harassment, 16 USC § 1362(18)(B), (C); however exposure to levels less than 180 dB (16 USC § 1362(18)(B), (D) ‘can cause short-term disruption or abandonment of natural behavior patterns’ (Pritzker 2016). These behavioral disruptions can cause affected marine mammals to stop communicating…,to flee or avoid an ensonified area, to cease foraging…, to separate from their calves, and to interrupt mating. LFA sonar can also cause heightened stress responses from marine mammals. Such behavioral disruptions can force marine mammals to make trade-offs like delaying migration,…reproduction, reducing growth, or migrating with reduced energy reserves. (Pritzker 2016)

In 2016, the United States Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reviewed the steps that NOAA Fisheries must follow before granting an incidental take permit under the MMPA for military readiness training. The case is instructive (and worth reading, see Unit 2 Resources) because it demonstrates the law’s rigorous standards in the context of an important and necessary activity in pursuit of national security.(Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. vs. Pritzker, 828 F.3d 1125, Ninth Cir. July 15, 2016) Brief SynopsisIn 2012, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS or NOAA Fisheries) approved a Final Rule (77 Fed. Reg. 50290, Aug. 20, 2012) specifically dealing with incidental take permits in conjunction with peacetime uses of Low Frequency Active (LFA) sonar for five years (as 16 USC § 1371(a)(5)(A)(i) provides). Claiming that the 2012 Rule did not adequately require the “least practicable adverse impact (16 USC § 1371(a)(5)(A)(i)(II)(aa))” on marine mammals, the plaintiffs sued to enforce this statutory mandate within MMPA. The lower court (United States District Court for Northern California) granted summary judgment to the agency. Upon review, the Federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed. Specifically, the Ninth Circuit noted the following in its holding: The 2012 Rule failed to contain means for effecting the least practicable adverse impact on marine mammals, stocks, and habitats, as required by law. Second, the Ninth Circuit found that the agency mistakenly conflated the two necessary standards (least practicable adverse impact, and negligible impact (16 USC § 1371(a)(5)(A)(i)(I)) and that, before authorizing any incidental take, both standards must be independently analyzed.Under the regulation implementing MMPA, negligible impact is defined as an impact resulting from the specified activity that cannot be reasonably expected to, and is not reasonably likely to, adversely affect the species or stock through effects on annual rates of recruitment or survival (50 CFR § 216.103). If the agency finds that a proposed activity will have negligible impact, it still must separately consider mitigation measures to reduce effects of the activity to the least practicable adverse impact (15 USC § 1371(a)(5)(A)(i)-(II) considered a stringent standard.Third, the Court noted that the agency was obligated to take areas of the ocean signified as “biologically important” by its own scientists into account when reviewing permit applications, whether or not the agency judged the existing data for those areas as sufficient—the agency was to rely on the data it presently has. The Court remanded the case for further proceedings.An appendix of Resources at the end of the book contains additional information relevant to protected species management (see resources for unit two).Unit 3 will discuss the tools for selecting and setting aside special geographic areas for species protection, management and conservation.

| Purpose/Theme | Section | Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listing | Section 4 | Five factors; agencies may initiate; ANY PERSON may initiate petition. Listing may ONLY be based on best scientific and commercial information. Economic impacts are prohibited and not considered. | 16 USC § 1533(a)-(c) |

| Critical Habitat Designation | Section 4 | One year after listing unless undetermined. Unlike listing, CHD must consider economics. | 16 USC § 1533(b)(6)(C) |

| Recovery and Monitoring | Section 4 | Involve Five-Year Reviews. Specific species information: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/endangered-species-conservation/endangered-species-act-5-year-reviews

Reports to Congress every two years; see https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/endangered-species-biennial-report-2014-2016 |

16 USC § 1533(f) and (g) |

| State-Federal Cooperation | Section 6 | The cognizant Secretary “shall” (mandatory) “cooperate to the maximum extent practicable with the States”…including the ability to enter into formal cooperative agreements | 16 USC § 1535 |

| Interagency Consultation | Section 7 | The Secretary “shall” review other programs s/he administers…all other federal agencies “shall” “utilize their authorities in furtherance of the purposes of this chapter by carrying out programs for the conservation of endangered and threatened species…” making sure efforts are consistent | 16 USC § 1536 |

| International Cooperation | Section 8 | Contains provisions authorizing the President to use various examples of funds and tools to provide assistance to other nations to develop and manage programs that support the species in question | 16 USC § 1537 |

| Prohibited Acts | Section 9 | Contains actions that are prohibited: import, export, take, possess, sell, deliver, carry, transport, ship etc. species in violation of the Act | 16 USC § 1538 |

| Permits | Section 10 | Permits may only be issued under certain circumstances; requires applicant to provide specific information regarding impact, mitigation, alternatives; requires Notice and Comment opportunity to the Public | 16 USC § 1539 |

| Penalties/Enforcement | Section 11 | Civil penalties, criminal violations,

provision for citizens to sue for enforcement |

16 USC § 1540 |

Unit 2 Study Questions

- Would simply listing species as threatened or endangered alone under ESA be enough?

- What are some proactive examples of management of species to avoid listing in the first place?

- Does the ESA include international species protection? What is the relationship of ESA to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)?

- Articulate the difference between the analytical steps that NOAA Fisheries must undergo before authorizing an incidental take under MMPA. Why does the difference matter?