Unit 3 – Managing Through Specially Designated Areas

Managing Through Specially Designated Areas

Contents

Introduction

Ecosystem Based Management (EBM)

Incorporating EBM and Prioritizing Conservation Objectives in Marine Planning

Introduction

Rocky reefs support a wide variety of species quite different from those that depend on sand flats. The coastal ocean teems with abundance and biodiversity and is a nursery for brooding and rearing for many species, including economically valuable fish, which, in their adult stages, are important for supporting commercial fisheries. The open ocean supports an entirely different complement of living organisms. The deep ocean contains unique species adapted to extreme conditions, including life on hydrothermal vents.

Ecosystem-based management pertains to a movement toward holistically understanding the ocean as a system, rather than a collection of species to exploit and manage. Species prefer certain types of ocean habitats, and cannot survive without the food and shelter that their particular ecosystems provide. Conceptually, then, the ocean is many different ecosystems nested into one large and dynamic system.

Advances in our understanding of the inseparability of habitats and the species that depend on them are reflected in contemporary environmental law (protection of habitat, ESA, Unit 2) and science alike. Technology, including ocean sampling, monitoring (both shipboard and satellite), and the spatial information provided by sophisticated Geographic Information Systems and Science (GIS) continue to support the revolution from single-species management to higher resolution ecosystem-based management. Now we can see the forest for the trees, to revise an old expression.

Ecosystem Based Management (EBM)

There are many different definitions of ecosystem-based management (EBM). Here are two useful descriptions. The first is from the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 2009. The entire report is available at msp.ioc-unesco.org

an integrated approach to management that considers the entire ecosystem, including humans. The goal of ecosystem-based management is to maintain an ecosystem in a healthy, productive and resilient condition so that it can provide the goods and services humans want and need. Ecosystem-based management differs from current approaches that usually focus on a single species, sector, activity or concern; it considers the cumulative impacts of different sectors.

This concept of EBM emphasizes connectivity between all systems (the ocean, atmosphere, and land) necessarily founded upon protection of the whole: structure, functions, and processes. The UNESCO vision recognizes that human dimensions are part of ecosystems: social, economic, and governance structures are also integrated into ecological systems. Finally, because we cannot realistically focus on the entire system at once, EBM is place-based, necessitating adapting the approach to specific ecosystems and their human impacts or influences.

A major concept in support of robust EBM (universally, not just in marine settings) is adaptive management. Informed decision-making moves forward with caution, even when data are incomplete. NOAA describes adaptive management in the following passage (NOAA 2018)

Adaptive management is an essential aspect of EBM; it is a way of managing the dynamic nature of ecosystems in the face of uncertainty by considering a broad range of influences within a region, including external influences, factors, and stressors. To increase effectiveness, adaptive management is often based on an open and mutually agreed upon process for monitoring and assessing the outcome of management actions; a process that allows for mid-course corrections to achieve desired outcomes.

Adaptive management also takes into account socioeconomic considerations, stakeholder participation, conflict resolution, legal and policy barriers, and institutional challenges. Being adaptive requires people and institutions to be flexible, innovative, and highly responsive to new information and experiences. Adaptive management succeeds when there are clear linkages among information, actions, and results and a strong climate of trust among partners. Considering local, state, federal, and international actions and sharing data are also critical to success.

At least three major points stand out in regard to EBM.

First, adaptive management is a priority. According to McLeod and Leslie (2009), ecosystem-based management in the ocean context requires a transition in focus from purely monitoring conventional indicators to including the monitoring of changes in processes (such as those that impact biodiversity) in order to understand reasons for the change.

Second, EBM realistically involves identifying and confronting potential resource tradeoffs. A prime example exists in establishing a management area where lower harvest levels are permitted in order to allow fish species to rebound. Explicitly considering trade-offs in a transparent decision-making process is intended to reduce surprises (unintended consequences) over time that could be damaging to ecosystems and their functions, and heighten tension and confusion among stakeholders. Trade-offs can be examined through a variety of options. One option involves assigning different values to the functions of the system (financial values “monetized” or non-monetized). Another approach is known as the ecological endpoints approach that measures production functions within a system. This approach uses two kinds of functional relationships (supply functions, or ecological production functions, or demand functions, an approach that analyzes relevant aspects of a user group, such as commercial or recreational fishing).

Third, holistic systems management anticipates cooperation and collaboration between governing entities. This is sometimes known as vertical or horizontal EBM. Vertical EBM is the coordination for consistent management from the bottom up, or the top down. Imagine vertical EBM as information sharing and planning across nested but discrete governance entities; for example, consistent cooperation and coordination throughout coastal city, county, state, region, national and international entities.

By contrast, horizontal EBM describes the collaboration and cooperation between entities at comparable governance levels: for example, in Oregon (as in many states), six to nine state agencies may be involved in a coastal decision. At the federal level, similarly several agencies may consult with each other over an ocean management decision, also consulting the appropriate state and regional authorities. Horizontal EBM can and often does include industry sectors as well. For example, the siting of an offshore alternative energy facility can include consultation with several different agencies at the state and federal levels, as well as a variety of permits and permit conditions. While each agency has individual (and complementary, sometimes overlapping or joint) legal and public resource stewardship responsibilities, they must coordinate their review and licensing of the proposed energy facility.

The energy-siting example would involve placing artificial structures in the ocean, requiring the designation of a certain kind of special area. The vast majority of special area management decisions are made in conjunction with restoring, maintaining or preserving areas important for species life stages, biodiversity, or other aspects of habitat structure and function. Each management area must be founded according to its species, resources, needs, stresses, and intended management purposes and goals.

Incorporating EBM and Prioritizing Conservation Objectives in Marine Planning

As long ago as 1972, Congress established the National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) System (in the Coastal Zone Management Act). This program can perhaps be seen as an early example of ecosystem thinking. The Reserve system contains 1.3 million acres and 29 estuaries where fresh water systems interact with salt water. The purpose of the program, administered by NOAA Office for Coastal Management, is to promote stewardship through research and education. Through the program, Congress recognized that estuaries are unique, economically critical environments that contain abundant ecosystem functions and services, including habitat (food, nesting, migration corridors, breeding) nurseries for important fisheries, water filtration, and buffering from coastal storms. The national reserves are collaboratively managed with coastal states. (NOAA Office of Coastal Management 2018)

Within Section 320 of the federal Clean Water Act, Congress established complementary non-regulatory estuary conservation program overseen by the US Environmental Protection Agency: the National Estuary Program (NEP). NEP protects water quality and ecosystems in 28 estuaries, managed by individual Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plans (CCMPs). The NEP is centered on collaborative public involvement; the priorities and objectives in the CCMPs are community based: determined by stakeholders spanning local, city, state, federal, private and nonprofit sectors according (EPA 2018).

A prime example of EBM-influenced spatial planning from a coastal state can be seen in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 2008, Massachusetts passed the Oceans Act (Session Laws, Acts 2008, Chapter 114). In 2009, the state passed the Ocean Management Plan, where one of the key planning purposes was for the proper siting of offshore wind energy. By engaging powerful fishing interests, the environmental and recreation communities, among other stakeholders, Massachusetts underwent an offshore planning and mapping process that took several years to complete.

The Massachusetts map reflects an off-limits area, two wind energy areas, and a multi-use area. The general division and labeling of offshore space was based on directing new ocean development away from ecologically sensitive areas (termed SSU for special, sensitive, or unique), in order to decrease competition and conflict between ecosystems and human uses of the areas. Logically, then, the planning and mapping process was preceded by data-gathering toward the establishment of an inventory of species and habitats offshore, but also including evaluations of resource areas most promising (and suitable) for wind energy.

Massachusetts revised the 2009 offshore maps in 2015. The data, process documents, and 2015 edition of the Ocean Plan are available at mass.gov. Volume 1 contains information relevant to management and administration; Volume 2 features the baseline assessment and science framework.

Two core habitats for whales (the North Atlantic Right Whale, and the Humpback Whale) were both increased based on data (effort-corrected sightings dating back to 1970 and running through 2014), using the adaptive management approach described above as a key part of EBM. North Atlantic Right Whales are protected under the ESA, MMPA, and Canada’s Species At Risk Act because they are among the most endangered in the world.

As a practical application of EBM, marine planning is flexible and adaptable. While it requires a major investment of time, funding, expert technical staff, scientific inquiry, and community involvement, marine planning is essential to marine conservation and the future provision of ecosystem services to society, particularly as resources shrink and human populations grow. The oceans seem vast to us, but they are not limitless. As with all Earth systems, oceans are dynamic and undergoing constant change. Impacts on the oceans from a warming planet make proactive, science-based marine planning more urgent. A major conservation-focused aspect of marine planning involves the establishment of marine protected areas worldwide.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) generally describe a wide range of levels of protection (including no-take areas known as marine reserves). In 1999, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defined an MPA as:

any area of intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed environment (Kelleher and Phillips 1999).

In the United States (by Executive Order 13158), a marine protected area is:

any area of the marine environment that has been reserved by Federal, State, territorial, tribal or local laws or regulations to provide lasting protection for all of the natural and cultural resources therein.

As defined by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), an MPA is

An area designated and effectively managed to protect marine ecosystems, processes, habitats, and species, which can contribute to the restoration and replenishment of resources for social, economic, and cultural enrichment.

Just as with habitat protection on land, connectivity is crucial; linking MPAs multiplies positive outcomes. Most species move, many migrate long distances, and all species use particular areas when breeding or rearing young.

MPAs are conservation centered, with levels of protection that are permanent and constant. Areas may be designated as closed to human activity altogether, or allow one or more activities such as diving, or even limited fishing.

United States waters cover 1.4 times the nation’s terrestrial area. As of 2017 (NOAA publication, Conserving Our Oceans, One Place at a Time) in the US, more than 12oo MPAs cover more than 3.2 million square kilometers—26% of US waters. Commercial fishing is prohibited in 23% of the US protected area. Only 3% of all MPAs in US waters provide the highest level of protection by banning all extractive uses. From 2005-2016, the quantity of area protected in the US increased by more than 20 times.

As EBM continues to be refined, the approach is major tool for holistic ocean planning around the world. Advancing the application of EBM spatially across eight national regions, NOAA is developing a program of integrated ecosystem assessments (IEAs). The initial eight regions are tied to eight Large Marine Ecosystems (LME).

Thirty years ago, the concept of LMEs was developed by NOAA and the University of Rhode Island as a means to implement EBM approaches to LME systems. Of the 64 global LME, 11 are in the US EEZ (NOAA Office of Science and Technology 2018). NOAA defines a large marine ecosystem is defined as “large areas of ocean space (200,000 km2 or greater) adjacent to the continents in coastal waters where primary productivity in generally higher than open ocean areas.” (NOAA 2018 (inactive link as of 05/21/2021))

Integrated Ecosystem Assessments (IEAs) collect essential information to inform better management decisions. Below are examples of data gathered or tools included in an IEA.

Data Examples

ASSESSMENTS

Status and trends of ecosystem condition

Ecosystem services

Activities or elements constituting stressors

PREDICTIONS

Future condition of the ecosystem under stress if no action taken

Future condition under variety of management options or scenarios

Evaluation of potential for success of various management options

NOAA Fisheries 2018

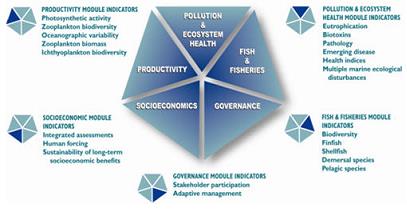

Designing and finalizing an IEA to determine ecosystem status involves deriving outputs from five different modules of indicators (spatial and temporal) illustrated below.

The appendix of Resources at the end of the book contains additional details relevant to managing through specially designated areas (see resources for unit three).

Unit 3 Study Questions

- What does Ecosystem Based Management require to be effective? Robust?

- What are the benefits of managing the marine environment through specially designated areas?

- Theorize and describe examples of technical or economic issues that managers could confront in stewardship of specially designated areas.

- From the perspective of managing present and future (often competing) human uses and impacts, what are the implications of ocean zoning and planning for society? For managers?