6.7 Calcium Homeostasis: Interactions of the Skeletal System and Other Organ Systems

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the effect of too much or too little calcium on the body

- Explain the process of calcium homeostasis

Calcium is not only the most abundant mineral in bone, it is also the most abundant mineral in the human body. Calcium ions are needed not only for bone mineralization but for tooth health, regulation of the heart rate and strength of contraction, blood coagulation, contraction of smooth and skeletal muscle cells, and regulation of nerve impulse conduction. The normal level of calcium in the blood is about 10 mg/dL. When the body cannot maintain this level, a person will experience hypo- or hypercalcemia.

Hypocalcemia, a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of calcium, can have an adverse effect on a number of different body systems including circulation, muscles, nerves, and bone. Without adequate calcium, blood has difficulty coagulating, the heart may skip beats or stop beating altogether, muscles may have difficulty contracting, nerves may have difficulty functioning, and bones may become brittle. The causes of hypocalcemia can range from hormonal imbalances to an improper diet. Treatments vary according to the cause, but prognoses are generally good.

Conversely, in hypercalcemia, a condition characterized by abnormally high levels of calcium, the nervous system is underactive, which results in lethargy, sluggish reflexes, constipation and loss of appetite, confusion, and in severe cases, coma.

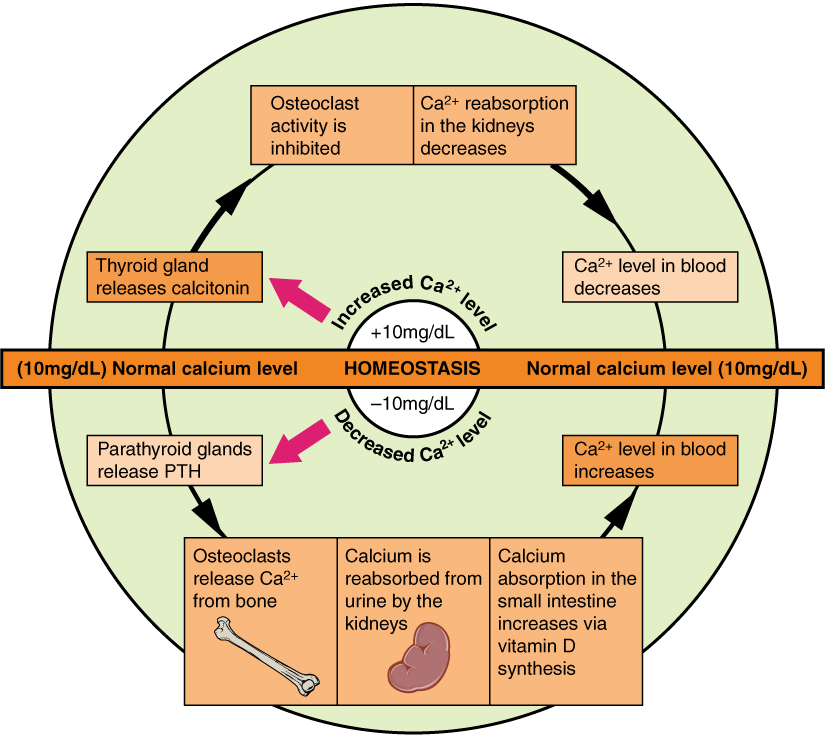

Obviously, calcium homeostasis is critical. The skeletal, endocrine, and digestive systems play a role in this, but the kidneys do, too. These body systems work together to maintain a normal calcium level in the blood (Figure 6.7.1).

Calcium is a chemical element that cannot be produced by any biological processes. The only way it can enter the body is through the diet. The bones act as a storage site for calcium: The body deposits calcium in the bones when blood levels get too high, and it releases calcium when blood levels drop too low. This process is regulated by PTH, vitamin D, and calcitonin.

Cells of the parathyroid gland have plasma membrane receptors for calcium. When calcium is not binding to these receptors, the cells release PTH, which stimulates osteoclast proliferation and resorption of bone by osteoclasts. This demineralization process releases calcium into the blood. PTH promotes reabsorption of calcium from the urine by the kidneys, so that the calcium returns to the blood. Finally, PTH stimulates the synthesis of vitamin D, which in turn, stimulates calcium absorption from any digested food in the small intestine.

When all these processes return blood calcium levels to normal, there is enough calcium to bind with the receptors on the surface of the cells of the parathyroid glands, and this cycle of events is turned off (Figure 6.7.1).

When blood levels of calcium get too high, the thyroid gland is stimulated to release calcitonin (Figure 6.7.1), which inhibits osteoclast activity and stimulates calcium uptake by the bones, but also decreases reabsorption of calcium by the kidneys. All of these actions lower blood levels of calcium. When blood calcium levels return to normal, the thyroid gland stops secreting calcitonin.

Chapter Review

Calcium homeostasis, i.e., maintaining a blood calcium level of about 10 mg/dL, is critical for normal body functions. Hypocalcemia can result in problems with blood coagulation, muscle contraction, nerve functioning, and bone strength. Hypercalcemia can result in lethargy, sluggish reflexes, constipation and loss of appetite, confusion, and coma. Calcium homeostasis is controlled by PTH, vitamin D, and calcitonin and the interactions of the skeletal, endocrine, digestive, and urinary systems.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

An individual with very low levels of vitamin D presents themselves to you complaining of seemingly fragile bones. Explain how these might be connected.

Reveal

Describe the effects caused when the parathyroid gland fails to respond to calcium bound to its receptors.

Reveal

Glossary

- hypercalcemia

- condition characterized by abnormally high levels of calcium

- hypocalcemia

- condition characterized by abnormally low levels of calcium

condition characterized by abnormally low levels of calcium

condition characterized by abnormally high levels of calcium